Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

There's an interview with me in the December issue of Locus, and here is a substantial excerpt from it: I talk about The Saint of Bright Doors and Rakesfall, and fantasy in general.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know that I shouldn’t be surprised anymore at vague “anti-AI” kinds of opinions, but I actually am a little stunned by the utter ignorance of what “computing” is that’s displayed here

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

really saying the quiet part out loud by revealing that your hatred of “AI” is intricately tied to your fervent belief in the redemptive and edifying powers of suffering—up to and including physical suffering—and the idea that students in particular ought to suffer

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

just saw multiple people asking in the comments of a post if they can use and wear a carabiner for their keys if they're bi or otherwise not a lesbian and I simply have to ask if people know that carabiners are used for many purposes beyond signaling lesbianism. like girl they were invented in the early modern period for their functional use as a clasp it's not like they're some closed lesbian practice......

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m reading (at least) a bit of Seo-Young Chu’s Do Metaphors Dream of Literal Sleep? because it seems likely to be at least somewhat relevant to one of my current projects, but while I like parts of the argument, I also kind of just...don’t think “representation” is a useful framework for thinking about what science fiction is or does. in particular, focusing on the objects of representation as the distinguishing characteristic of science fiction* seems to me to put us right back at “sci-fi is when there are laser guns”.

more to the point, it still means treating genres as inherent and objective characteristics of given works (though Chu does note that works may become more or less “estranging” as time and context changes) rather than recognizing that they are, fundamentally, a) marketing categories and b) methods for making sense of particular works (what Delany calls “reading protocols”). it’s certainly true that particular works cue us to read them with particular protocols in different ways, including by means of their content, but as Chu herself observes, content-wise it’s all a difference of degree, rather than of kind.

(this is also a somewhat ungenerous read, insofar as really what she’s doing is articulating an understanding of science fiction as a mode à la Attebery, but that doesn’t really avoid the problem imo; it just changes the terminology.)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

kamet and costis as undercover lesbians disguised as men and on the run

my FTH gift to @whocalledhimannux!

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love the implication that the Glinda and Elphaba just sit across from each other, alone at this giant table just to stare at each other and contemplate how much they hate each other and the whole school knows not to go sit with them an intrude in whatever they have going on

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

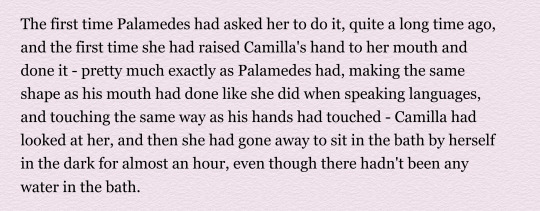

"Camilla Hect, yet another of devotion's casualties"

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

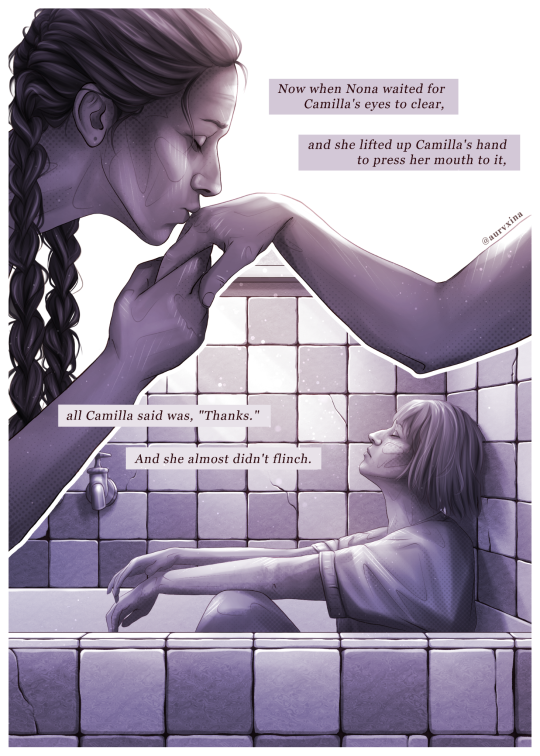

mama a Body behind you 😰 // pt1/pt2/pt3

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

the phenomenon of people talking about the cost of "AI" in energy and water while ignoring everything else they use that also spends those same things is very telling

you do not know the process behind production of the things you take for granted. you think your computer is a magic box that connects to the astral plane. you never think about the cables and servers and water cooling and electricity cost and the workers who build and maintain the infrastructure etc. etc. except for the thing you don't like and were told the cost was a good excuse for why you don't like it

you also don't think about the cost of so much more. the food you eat, the phone in your hand, etc. you just know it costs an amount of dollars at the store

this isn't about being a morally bad person for not thinking about this. this is about not getting bogged down on the supposed inherent evil of 1 specific thing you were told to hate because it's the only thing that you realize needs to be produced using material resources. and instead becoming a marxist

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

their height difference!!

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

hamlet x ophelia mixed messages amv

663 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the best days I ever had climbing was when my friend and I went to a local crag and met this insanely cool woman - my guess is she would have been in her 60s. She'd taken up climbing with her daughter's friends because she was in between seasons practising medicine in Antarctica (which apparently involves jumping out of helicopters). She'd finished her second season and was getting ready for her third. She came over and gave my friend and me lolly snakes because it was "nice to see young women climbing hard" and we were tripping over ourselves like NO MA'AM YOU ARE THE INSPIRATION!!! Genuinely if ever I found myself thinking that life was over at 30 I would think of her and be instantly cured.

I think being afraid of becoming 25 can be combated by like literally hanging out w people of all age groups and realizing that they too have personalities and hopes and dreams and goals and life is not over for you at like 30

10K notes

·

View notes