thoughts that arise mostly in the darkness before the dawn

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

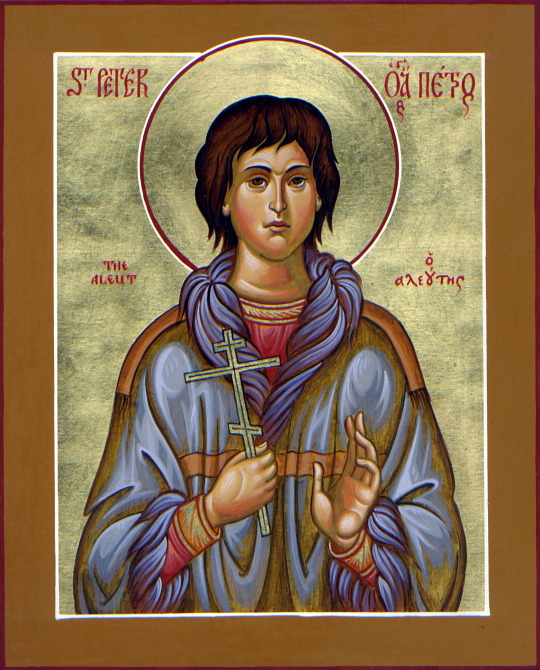

a different kind of martyr

Some 17 years ago, I had to find my patron saint. Most Orthodox don't pick their own; it's generally assigned at birth or close enough it amounts to the same thing. But when I converted as an adult, I got to choose saints for myself, my kids, and (as it turned out) my wife.

You have to feel the sarcasm dripping off that "got to"--I don't do intuition or spiritual experiences, so it was not a welcome opportunity. Maybe if I'd realized that it didn't have to be forever, it would have felt a little less daunting. There's no particular reason you can't have a special connection with more than one saint; and in my case, I had the perfect opportunity to switch if I'd wanted to. Due to a clerical oversight, our baptismal certificates weren't processed until I thought to ask more than a decade later; and in the event, they accidentally assigned my son's patron to both of us on paper. But I'm nothing if not committed, so I have no interest in changing--even if there's no formal documentation, even if he might not be real, even if his story is grossly problematic for Christian unity.

Looking back over my list of reasons, it's nice to see that most of them need no revision, except this one:

Sort of related to the previous connection, he was martyred by Catholic missionaries. I'll say to start out that this doesn't inspire in me a hatred for Catholics. But it does speak to both the "Western" chauvinism that infused colonial efforts and the tendency in "Western" Christianity to discount the authenticity of the "Eastern" faith. (I'm using quotes here, because in this case the Orthodox are coming from the West and Catholics are coming from the East.) I would say this tendency applies just as much to Protestantism, whatever one might say about whether Protestants would have martyred Peter for refusing to convert. I suspect I'm always going to have to deal with my fellow Euro-Americans questioning the legitimacy of my Orthodox faith, and it will be good to have a saint who understands so intimately that struggle.

I think I've come around to a more balanced view of Eastern and Western problems, as I noted six years ago when I had a chance to visit Mission San Gabriel. Russian colonialism wasn't necessarily any better than Spanish; it sent native Alaskans 3000 miles from home to California and provoked a clash of empires that ground them to dust. Likewise, Eastern Christianity has made more than its fair contribution to religious strife. And as an Orthodox Christian born and bred in the West, I get to own both sides.

I still love St. Peter, because he's not to blame for any of this; he was a victim of circumstance, but his simple faith still speaks for itself. He wasn't trying to convert anyone or win points in a war; he just wanted to be heard and seen for who he was. The problem comes when we use his legacy to further our own prejudice.

Perhaps an analogy would help. There's been a long-standing problem with Christians using the "Christ killer" label against Jewish people throughout history. Now, it is true that Jewish people killed Christ, or at least wanted him dead. Not all of them, or even most of them. And Jesus himself and his disciples were also Jewish. But the point is certainly made in Scripture that Jewish people killed him. And if we leave it there, we might feel it's a justifiable claim. But we have to ask why it's framed this way at a time when Christianity was still very much a Jewish movement. He came as the Jewish Messiah, and his own people--those who should have received him--called for his death. That's relevant not because they're Jewish (as one race among others), but because they were his own people. The Christian response should not be to assign blame but to ask, if we are his people, how do we put him to death by our actions? If it comes to assigning labels, then we are the Christ killers.

Now, here's the analogy: if Peter the Aleut was tortured and killed by some Catholics in California, what does that mean? Why is it important that they were Catholics? Any Christian martyr can be killed for their faith by pagans or Muslims or atheists, and die with a great confession of Christ on their lips. But St. Peter died for his faith at the hands of Christians, who didn't need an equal-to-apostle to introduce them to Jesus. And while they may have missed some important points, they already had their own martyrs to show them the way of the cross. St. Peter's great witness was that he died at the hands of Christians--that after the law and the prophets and the gospel and 1500 years of Christian civilization, we could still so easily commit the original sin of fratricide. That in the name of Jesus, who showed us how to lay down life for our brothers, we could take their life instead. That we could travel half-way around the world to carry the gospel, meet Christians coming the other way around, and plant our flag through their heart to claim we got here first.

The meaning of St. Peter's death is not that, as we always knew, those Catholics are evil. It is a mirror to show us how miserably we all fail in our witness to Christ. To show how our cause blinds us to the person before us. To question whether we're really fighting for God's truth or for our own scrap of territory. If his death has meaning, it can only be that we killed him.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

İstanbul (was قسطنطينيه)

İstanbul is quite probably number one on my bucket list of places to visit. At first glance it doesn't seem like it should be--the Holy Land would make more sense for several reasons. I don't fully understand it myself, but I can take a stab at a logical explanation; it's probably not exactly what you might think.

Let me first address the sticky question of nomenclature. The City we're talking about here has enough names to warrant a Wikipedia entry, and people can get fairly opinionated about which one is "right." As an Orthodox Christian, you might think I'd opt for Constantinople; but before that I was a philologist, and old habits die hard. İstanbul comes from a Greek phrase that meant "to the city"; it predates the Ottoman conquest and reflects a widespread reputation that transcended any need for specificity. Both names were used, along with a host of others, before, during, and after the empire founded by Fatih Mehmed. As far as I'm concerned, one works just as well as the other; the reason behind the modern preference really is "nobody's business but the Turks."

Anyway, to the point at hand: İstanbul lives first in my heart as a literary destination. I probably didn't realize this before reading the stand-alone historical novel entitled simply Byzantium, by Stephen R. Lawhead. I'm sure I read it in 1996, the year it was published, which was also the year I got married. Lawhead was my favorite living author at the time, and I read everything he wrote, almost as soon as it came out. Interesting story about that book--eventually I donated it my church library, and then bought it back at a sale years later so I could read it one more time. (It was OK, but not as good as I remember thinking the first time around.)

It would take me somewhat longer to realize that İstanbul was the inspiration for Tashbaan in the Chronicles of Narnia and probably for Minas Tirith in the Lord of the Rings, both of which I read repeatedly while growing up. It's also an important setting for the Historian, by Elizabeth Kostova, which I still maintain is the most perfect novel ever written for the average American Orthodox convert. (Not to mention, a great starting point for planning a European road or rail trip.) Add Umberto Eco's Baudolino, Rose Macaulay's the Towers of Trebizond, and Nektaria Anastasiadou's a Recipe for Daphne, and you start to get the idea--whether in its medieval, mythical, or modern form, some of my favorite stories would be almost pointless without the City.

And is it any wonder? İstanbul stands at the gateway between Europe and Asia. It was the western hub of the famed Silk Road trade routes. Largely because of this strategic location, Constantine chose Byzantium as his new capital, after which it served for almost 1600 years as the seat of one empire or another. It didn't just inspire stories; it inspired kingdoms. Attackers didn't seek to destroy it but to become it. At its lowest ebb, when the once-mighty Roman empire had dwindled to a beleaguered city, it was finally conquered by the ambitious Ottoman Mehmed II. But instead of falling into oblivion, it defined his new empire as a Third Rome, spreading its wings once more across two continents. This is the city that needs no name.

Now don't get me wrong--I'm not pining for dead empires or seeking to resurrect them. I know all too well the congenital defects of Eastern Orthodoxy that stem from its dependence on the Christianized state--from its subservience to tyrants, to its stunted sense of mission, to its paralysis in the face of modern challenges. I know also the pain we've suffered under both hyper-religious and secular nationalist regimes. But I appreciate how much we can learn from history, both the good and the bad. And I'd rather experience history in the places where it happened than tucked away in a museum somewhere (usually by a foreign power that feels entitled to claim someone else's artifacts).

And that brings me to another complicated reason that I want to visit İstanbul--religion. Of course, it was the seat of Christian Empire for many centuries, which irrevocably shaped the Eastern Orthodox Church into what it is. But more recently it played host to the last great Islamic Caliphate under Ottoman rule, and the city bears marks of both to this day. Its grand historic churches survived as converted mosques; in the 20th century, some were set aside as museums, but the present government has turned them back over for religious use. In most cases you can still see the old Byzantine iconography preserved in one form or another, but it is painful for many Christians that you have to plan your visit around the schedule and sensibilities of worshiping Muslims.

Personally, I have somewhat mixed feelings about the situation. It would be nice to see the Ayasofya unobstructed, as it was in its days as a museum; but then it was a museum, which I don't find a particular improvement. Justinian built it as a house of worship--for many centuries, the most impressive church on the planet--and if Christians couldn't keep it, I would rather see it preserved as sacred space than crumbling into ruin or locked away under glass. It simply is not going to be a church again; even if it were by some miracle handed over to the Orthodox Christian community, it would be an absurd facility to maintain for such a tiny population, and it would bankrupt them to do so. For better or worse (and at least partly due to our own poorly conceived plans), the great churches of Constantinople past now belong to the predominantly Muslim Turks. Their fate is in their hands, and I am glad at least that it fell to a religious people, who usually found more value in them than as storage containment or to be demolished in favor of modern development.

Whatever else an edifice like Ayasofya may be, it is a symbol--of many things, perhaps, but at least that a nation is consecrated to God. It would be incongruous if such a prominent symbol did not align with the spiritual orientation of the people. I may disagree with some of the content of their faith, but I cannot altogether discount the devotion that has preserved this space and filled it with prayer over the centuries. So I hope to visit the historic imperial churches, but also to honor the mosques they have become, in which form they have continued to live, rather than die in the dust of ages past.

And what of the people? I hope it is clear by now that I want to touch the relics of history and faith, but specifically in their current, living context. More than that, I also want to encounter the culture and people that exist there today, however much may have changed since the height of the Christian Roman Empire. I hope to catch a glimpse of the Rum Ortodoks community that persists to this day, though I don't know how easy it will be to do that. I've mapped out some of the locations mentioned in a Recipe for Daphne, and I plan to attend services in at least one of the functioning churches of the modern district of Beyoğlu/Pera. I'm learning Turkish and some Modern Greek, so I can interact as much as possible with the locals throughout our visit. This will be my first foray beyond the bounds of strictly European culture, and I want to observe, and listen, and learn.

Of course, it's hard to avoid bringing my own political ideas with me. As an Orthodox Christian, it's natural for me to sympathize with the Christian community and their struggle for survival. But I also want to understand the Turks as a people through more than just the lens of nationalism and ethnic cleansing. As an American I have no moral authority to judge others exclusively in terms of their bigotry or oppression. I want to believe that we can all change for the better, that we are not forever defined by the worst impulses of our society. I hope we can find a better way, but I don't have any good solutions to offer. Maybe by traveling with an open heart and encountering others honestly, I can become better than I am; maybe that's all any of us can do.

Reading back over this post, I can see an inescapable tension. I vacillate between thinking of myself as connected to and as separate from this heritage. As a formerly WASP American convert, it's inevitable. You can't really be Orthodox without being Eastern, but neither can you simply absorb wholesale a different cultural identity. The best I can manage is to live with the tension of not fully belonging anywhere. And I realize this makes my viewpoint suspect to pretty much everyone concerned. All I can offer is respect for experiences and perspectives that are not mine.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I love the carol "Good King Wenceslas," and when I discovered that this special issue contained an illustrated rendition, I put it on my Christmas list.

I don't spend much time with superhero comics, and I can't recall ever reading anything related to Aquaman. (I made it about 5 min into the movie, and that was on an international flight without much else to do.) But this story turned out to be my favorite in the book.

It fits well with some of my other Christmas favorites: "Cherry Tree Carol," "The Bitter Withy," and various apocryphal stories about Jesus and Mary. And it evokes an obvious connection with "I Saw Three Ships."

DCU Holiday Special - “Somewhere Beyond the Sea” (2008)

written by Dan Didio art by Ian Churchill & Bob Rivard

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christianity and Other Sacred Traditions

I grew up with a firm conviction that Christianity was The Truth, and all other religions were at best so much human striving, or at worst demonic deception. A lot has changed in my thinking over the past three decades, and while I still feel most at home in Christianity, I would say now that I want to believe the Truth is bigger--that there is value in other paths to enlightenment.

Recently I encountered a footnote to Philip Sherrard's chapter on "Christianity and Other Sacred Traditions" from his last book, published posthumously as Christianity: Lineaments of a Sacred Tradition. The reference left an impression echoed by the Foreword, where Bishop (later Metropolitan) Kallistos Ware writes about the chapter in question:

Philip was genuinely Orthodox, but his vision of Orthodox Christianity was generous and wide-ranging, not defensive or timidly parochial. All too many Orthodox Christians today understand their faith as negation rather than affirmation. Philip rebelled against this (xix).

I was able to secure a copy through interlibrary loan, and since I can't find the full text anywhere online, I thought I'd share some highlights from his argument. It begins somewhat in the preceding chapter, on "Christianity and Christendom," with the continuity between Christianity and the preceding intellectual and spiritual traditions:

The relationship between Christianity and the Essenes is not clear. But what is clear is that however much Christianity is a culmination or fulfillment (and in what respect it is so is often very vague, even to Christians), nonetheless Christianity stood in the line of a tradition of wisdom and knowledge whose historical appearance is long prior to the advent of Christianity. It is ridiculous to go on applying to that whole period before the historical birth of Christ the term "pagan'' -- which came into use somewhere about the fourth century AD -- in order to describe derogatively the peasant sorcerers who preserved, generally in an entirely debased form, something of the magical arts of the ancient world. It is still more ridiculous to do this with the implication that the historical birth of Christ marks a complete break with the intellectual and religious traditions of the ancient world, as if the thought and religion of the ancient world were all so much error and falsehood and as if its faith were superficial and misguided. This is not only to forget such monuments of intellect as Herakleitos and Plato; not only to forget the non-Christian martyrs who suffered for their faith tortures as cruel as any suffered by the Christian martyrs, and borne with the same courage and integrity. It is also to forget that it was through the writings of such as Plato and his successors that many of the Christian Fathers -- St. Augustine among them -- were brought to Christianity. It is to forget, too, that the language of many of the Christian Fathers (and particularly of the Greek Fathers), as well as the language of the liturgies, is the language of Neoplatonism, and that when Christians came to elaborate their theory of sacred art (represented in the icon), it was in Platonic terms that they did so. Indeed, if one is to go back to the testimony of many of the early Christian writers themselves, one might well be led to the conclusion that Christianity is little more than the restoration or revitalization of the religious traditions of the ancient world in their highest form. According to Eusebius, for example, Christianity is the restoration of the religion of the patriarchal age, which had been debased and distorted by subsequent Judaism; and St. Augustine himself writes: "That which today is called Christian religion existed also among the Ancients and has never ceased to exist from the origin of the human race until the time when Christ Himself assumed human form and men began to call Christian the true religion which already existed beforehand." In these early stages, too, there was much in Christian form and practice that was reminiscent of the initiations or the esoterism of the ancient mysteries like those of Eleusis, or Samothrace, or Lemnos. There was a lex arcani. Origen talks of faith being useful for the masses, and further says that the intelligent are more congenial to God than the unintelligent. He explicitly speaks of secret doctrines that can be taught only to the initiated. Clement of Alexandria says the same thing, and such a secret (and oral) tradition is referred to by St. Cyril of Alexandria, St. Gregory Nazianzen, Dionysios the Areopagite, and many others. Unless one is automatically prevented by prejudice, one has to recognize that in its essential form Christianity is an initiatory religion that is in many ways similar to the mystery religions of the pre-Christian world (28-29).

But this is getting a bit ahead of the fuller argument. As Sherrard opens the chapter on "Other Sacred Traditions," he asserts that "one of the conditions of any renewal within the Christian Church is that the Church renounces the claim that the Christian revelation constitutes the sole and exclusive revelation of the universal Truth" (53). More than just a practical consideration,

It is a question about the Truth itself. If the Spirit is present and operative only within the framework or the bounds of the Christian Church as a historical institution, then the way in which the spiritual life is lived is one thing; if He is present and operative in many other forms throughout the world, it is quite another (54).

Sherrard finds among the early Christians both a negative and a "more positive attitude implicit in Paul's speech to the Athenians":

This attitude was given a basis in doctrine by many Christian theologians. As one might expect, it was related to the understanding of the divine Logos and His incarnation in human form. For Justin Martyr, for instance, a seed of the Logos - the logos spermatikos -- is implanted in the whole human race and throughout creation before Christ's birth in the flesh, so that those who lived according to the Logos, like Socrates and Herakleitos among the Greeks, and Abraham and Elijah and many others among the "barbarians", were Christians before Christ. Clement of Alexandria sees the whole of mankind as a unity and as beloved of God. Basing himself on Hebrews (1:11), he affirms that it was not only to Israel but to the whole of mankind that "God spoke in former times in fragmentary and varied fashion". Mankind as a whole is subject to a process of education, a pedagogy. The whole world "has had as its teacher Him who filled the universe with His energy in creation, salvation, beneficence, lawgiving, prophecy, teaching and indeed all other instruction''. Within this divine economy, philosophy has a special role: it is not merely a stepping-stone to a specifically Christian philosophy. It is even "given to the Greeks as their Testament". Greek and by implication all other non-Christian philosophies are fragments of a single whole which is the Logos (56).

This presence of the Logos throughout all humanity and all creation before his advent in the flesh is affirmed in other patristic writers:

Faced with the question of whether what Christ's mission signifies is a reaffirmation of an understanding of things that had always been known, and by some fully known, but had been forgotten or distorted, or a radical change in the nature of reality itself, and hence in the nature of what is to be known, Origen chooses the first alternative. There is, he writes, "a coming of Christ before his corporeal coming, and this is his spiritual coming for those men who had attained a certain level of perfection, for whom the whole plenitude of the times was already present, as for example the patriarchs, Moses and the prophets who saw the glory of Christ." The prophets, he adds, "have received the grace of the plenitude of Christ . . . " and "led by the Spirit they have attained, after having been introduced to the figures (typoi), to the vision itself of the truth". For St. Maximos the Confessor, before His advent in the flesh the Logos of God dwelt among the patriarchs and prophets in a spiritual manner, prefiguring the mysteries of His advent. A similar attitude is to be found in certain western theologians. A figure as venerable as St. Augustine affirmed that since the dawn of human history men were to be found within Israel and outside Israel who had partaken of the mystery of salvation, and that what was known to them was in fact the Christian religion, without it having been revealed to them that this was the case. And St. Irenaeus sums up this line of patristic thought when he says "there is only one God who from beginning to end, through various economies, comes to the help of mankind" (57).

Thus Sherrard concludes from these theological reflections:

that all human nature -- in fact, all created being -- participates in divine life, whether single individuals are aware of it or not. Each single human being, through energizing in his individual life that original Adamic nature in each of us which has been fully restored or resurrected or transfigured in and through the incarnation of the Logos, can realize his own participation in the life and character of ultimate Reality itself (58).

Why, then, have Christians tended to think more exclusively of salvation within the institutional Church? According to Sherrard:

This attitude stems from a linear view of history bound up with a monolithic ecclesiology which sees Christianity as a series or succession of salvation events destined to culminate in the appearance of Christ as the end of the history of the Old Covenant and as the end of human history. It is a view which tacitly ignores the idea of an ever-present eternity that transcends history. Similarly it ignores the idea of the Church in which Christ the Logos is seen, not merely chronologically but ontologically, as the immanent principle of the mystery in which the divine is disclosed at every point of time and in every creature, so that every human being and every created thing is a theophany and stands in an immediate, trans-historical relationship to the divine archetype of which he or it is the manifestation. Concomitantly, it also tacitly ignores the idea of the universality of the Incarnation: that the divine event signified by the Incarnation is not simply the incorporation of the Logos in the body of a single historical human being but also, and more importantly, an incorporation of the divine in the human as such, so there cannot be an individual human being of whom the Logos is not the ultimate subject, however unactualized He may be in any particular case (59-60).

This historical view minimizes the contemplative vision inherent to Christianity and "makes dialogue with other religions, especially with the dominantly contemplative Asiatic religions, virtually impossible":

In fact, if Christians are to integrate other religions, positively and creatively, with their own doctrinal perspective they have to go beyond and discard this concept of linear "salvation history" which represents the final flowering of that negative attitude of exclusivity which Christianity has inherited from Judaism and which, as we saw, is already explicit in the Acts of the Apostles. This attitude must be replaced by a theology that affirms the positive attitude implicit in the writings of Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, the Cappadocians, St. Maximos the Confessor, and many others. The economy of the divine Logos cannot be reduced to His manifestation in the figure of the historical Jesus: the idea of God-manhood possesses a significance that is intrinsic to human nature as such, quite apart from its manifestation in a historical figure who exemplifies it. Correspondingly the Church cannot be reduced to a visible institutional and sociological form. The Church, in Origen's words, is the cosmos of the cosmos. It is the innermost reality of humanity and of creation its elf, even if this is not recognized. It is the locus within which the Christic mystery is continually unfolded. It is also the locus of the Pentecostal event -- of the manifestation of the Holy Spirit who in person reveals to creation the interior presence of the Logos. It is the task of Christians and above all of Christian theologians to recognize and affirm this presence and this mystery not only within the boundaries of the historical Church, but also in those other testimonies to this presence and this mystery that are to be found in other religions (61).

Despite the differences between religions the Logos is hidden everywhere, and other types of his reality are equally authentic:

any deep reading of another religion is a reading of the Logos, of Christ. It is the Logos who is received in the spiritual illumination of a Brahmin, a Buddhist, or a Moslem. Indeed, if the tree is known by its fruits, only spiritual blindness can prevent us from recognizing that those who live and yearn for the Divine in all nations already receive the peace the Lord gives to all whom He loves (Lk. 2:14) (62).

Why, then, do different religions appear incompatible?

Truth is one; but in expressing Itself in a way which is accessible to the human intelligence, It has to take account not only of the limitations of the human state as such, but also of the various, though relative, divisions within mankind that are themselves expressive of various facets of the divine plenitude. Put in its broadest terms, one might say that the differences between the various traditions are due to the differences in the cultural milieux for which each is providentially intended and to which each has therefore to be adapted (62-63).

Because of this human limitation:

At different times and different places, the Supreme, either through direct revelation of a Messenger or Avatar, or through the inspired activity of sages and prophets, has condescended to clothe the naked essence of these principles in exterior forms, doctrinal and ritual, in which they can be grasped by us and through which we can gradually be led into a plenary awareness of their preformal reality. These forms may be many -- in a sense there may be as many ways to God as there are individual human beings -- but beneath this multiformity may always be discerned, by those who have eyes to see, the essential unity of the unchanging, non-manifest, and timeless principles themselves (63).

But even after acknowledging that Truth can be communicated in different forms, might we not still find that one particular traditions is superior to others? Sherrard points out the inherent circularity of such judgments:

In effect, to resolve an apparent conflict or disagreement between traditions one requires initial principles in the light of which it can be resolved. These principles one may say are "laid up in heaven", and this is a justified attitude as long as one is content to leave the apparent conflict or disagreement to be resolved "in heaven". But as soon as one seeks to resolve it through humanly intelligible interpretation, then one must bring one's principles down from heaven and recognize them in a humanly intelligible form -- in, that is, the doctrinal form of one of the traditions which, because of its superior nature, is capable of resolving the conflict or disagreement with which one is presented (65).

Since as humans we cannot really come at things from a universal perspective, we have to assume about our knowledge something that is impossible:

As we have seen, the degree of knowledge one possesses will be that represented in the tradition from which one has obtained it: otherwise one would not be in possession of it. To say then that this is the highest degree of knowledge, the fullest expression of the Truth possible (which one must say if one is to carry out the act of discernment with which we are concerned), and consequently that the tradition through which one has obtained it is a universal tradition in the full meaning of the words, is simply to argue in a circle. It is to use as one's criteria of what constitutes the highest degree of knowledge, and hence of where this is fully represented, precisely those principles enshrined in the tradition from which one has obtained them in the first place (67).

This point is both logical and theological, as Sherrard explains from the Christian standpoint, where divine revelation must bridge the gap caused by our human limitation and fallen condition:

Divine revelation cannot but accommodate itself to the mode of existence and knowledge -- the mode of consciousness -- of the being or beings to whom it is addressed, for the simple reason that unless it is so accommodated it cannot be experienced or received. There is absolutely no point in God revealing His Truth to me in a way that I am incapable of experiencing or receiving it. At the same time, the Holy Spirit does not force people, and He cannot inspire people beyond their capacity to receive inspiration. Correspondingly, the most lucid revelation is concealed from us when we have become incapable or unworthy of perceiving it. If I and the section of humanity to which I belong are incapable of receiving and experiencing the Truth except in a form that is perceptible to the senses, then the Truth must put on the "robe", or the appearance, of the dark world into which it has to descend in order to communicate itself to us. It has to clothe itself in sensible images, of one form or another. In making such a descent, or in putting on such a robe, the pure light of the Truth is in its turn occluded, hidden, and veiled by the darkness of our ignorance, ineptitude and sin (72).

This darkness necessitates the particular human form of God's self-revelation:

In this sense, both the Incarnation and the Crucifixion are the consequences of our ignominy. This is nothing for Christians to be proud or self-congratulatory about. Had the Judeo-Hellenistic world, the type of consciousness that typifies it, been capable of receiving that revelation in a more subtle or more spiritual form, then it would have been communicated in such a form. Correspondingly, the fact that the revelations of other sacred traditions are not centered in and do not depend upon an incarnation equivalent to that of Christ does not mean that what they claim to be the wisdom enshrined in their doctrine is spurious or false, or is in any way inferior to the wisdom enshrined in Christian doctrine. It may simply mean that the consciousness of the milieux, human and cultural, to which these revelations are given is of such a type or quality that God does not have to manifest Himself in a visible, historical human form in order to communicate a true knowledge and understanding of things. Or, to put this in another way, it could be said that had God manifested Himself in such a form to these other milieux, He would not have been crucified (72-73).

In conclusion, Sherrard counsels humility:

As I said before, none of this means that all religious traditions that claim to be based on a true revelation of God are in fact based on such a revelation; nor does it mean that even when religious traditions are rooted in true revelation, one of them may not express God's wisdom and knowledge more fully than the others. What it does mean, though, is that the fact that a particular religious community embraces a form of belief and worship rooted in divine revelation, and entirely valid for human salvation, does not in the least justify that community in maintaining that its form of revelation, and the tradition rooted in it, are the only such form and tradition through which salvation may be obtained. Our primary loyalty and faith must of course be directed towards our own tradition and to deepening experience of that -- though even here we must remember that the significance that our tradition has for us, and the degree and firmness of the assent we give to it, may well depend not so much on its own inherent "objective" qualities and possibilities as on the strength of our acceptance of it, or faith in it, in the first place, and that this may be conditioned by many factors, cultural, ethnic, political and so on, that have little to do with the tradition in the spiritual sense. If we are at all concerned with the inner nature of other traditions we must seek to understand them as fully as we can in the light not of our own prejudices, but of their own criteria, bearing in mind always that no one can be aware of the living dimensions and potentialities of a particular sacred tradition without first experiencing them through active participation in that tradition's forms of belief and liturgical practice (73-74).

He finally urges once again a renewal of the Christian contemplative tradition:

Christian contemplation, in common with that of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam, is centered not upon some vague inner apprehension of the mystery of man's own spiritual essence. It is centered upon God's self-emptying, the kenosis, which must have its counterpart in man's self-emptying, the emptying of all purely human knowledge and even of man's whole ego-consciousness. We have to lose our soul in order to find it, or in order to be in a position to encounter directly the light and power of God. It is precisely here, at the heart of the Christian way, where we encounter the Christian expression of the dialectic of fullness and emptiness, all or nothing, void and infinity, that we can make a creative response to and engage in a creative encounter with the profound realizations that lie at the heart of other sacred traditions. Outside this ground, or short of it, we will always be in a state of non-comprehension, confusion or conflict (75).

As I said at the outset, I want to believe Sherrard is right. I do recognize (as he acknowledges) that there has been a strong tendency in Christian and other monotheistic traditions to present the gospel in exclusive terms--that this is the Truth, and we are responsible to share it with the world. But I also find compelling Sherrard's argument that revelation is always partial, and I wonder how this one version of Truth could bear the full weight of God's loving intention for the world. I don't doubt the power of the Christian gospel to reach across cultural boundaries, but I'm also prepared to embrace a healthy agnosticism about whether God's Truth exists in other forms. If it turns out that there are other paths, I can only rejoice that his witness is not constrained by the weakness of Western culture.

0 notes

Text

Zippy the Electric Car

I prepared for our European vacation by refreshing myself on driving with a manual transmission. When we went to the UK we reserved an automatic. I figured driving backwards would be challenging enough without having to shift gears, and the SUV we had to get was pretty much what we needed for a family of four with luggage. This time, I was anticipating narrow European roads and figured we could only get a smaller car in a manual. Apparently I needn’t have bothered.

When we picked up our car, they had only electric in our size range, which meant it was automatic, but also came with its own challenges. We had no experience with a plug-in electric car and didn’t really want to learn while on vacation. C’est la vie.

As it turns out, we’ve been pretty happy with our little car. It handles well on the twisty, windey roads, and it accelerates and decelerates as much as we need with all the up-and-down mountain driving. (It feels a bit like go-carting.) It also recaptures energy while coasting or braking, so it seems to get quite a bit more than the advertised 400 km from a full charge.

We’ve also discovered that several hotels provide charging stations. If you can live with an overnight trickle, your car can be topped off and ready to go the next day. You can also find high-speed chargers if you need them, and the price is much better than gas. We’ve been seeing around 2€25 per liter, which works out to about $9/gal. The one time we’ve paid to recharge, we were down around 19%, and it cost $25 to fill. We’re saving a lot of what we expected to pay in fuel costs for a week of driving around Corsica.

The one drawback is time. Even with a high-speed charger, it can still take an hour or two to fill. (People keep saying 40 min, but that hasn’t been our experience.) And you can’t always get a convenient overnight charge. The “nicest” hotel we’ve stayed in didn’t provide stations, and another just had an extension cord. It seemed to handle two cars at once, but you had to watch for the cord getting turned off, and a power outage the night before we left meant our longest drive started from only 65% capacity. So I can still understand hesitance around how much it might limit your ability to move along on longer trips.

All in all, though, it’s been nicer than I expected. It may not be an ideal solution for everyone yet in a place like America; but for rentals especially, it seems like there’s good incentive to get hotels on board and save some money traveling. Especially with the way gas prices are going these days.

0 notes

Text

Cargèse

To celebrate our 25th wedding anniversary, I had a suggestion--what about visiting the Mediterranean island of Corsica? Now, if you know me well, you know that I have a fairly long list of places in the world I would like to visit; you also know that most of them are not generally preferred vacation destinations: tundra over tropics, Asia over Europe, Black Sea over Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean over Western. But of course I had my eccentric reason for suggesting Corsica--it moves us one step closer to the goal of visiting our four family patron saints. St. Julia is sometimes "of Carthage," where she was born, but she is patroness of Corsica, where she died. The rest of the conversation was pretty easy--Julie quickly fell in love with the scenery, and a 2-1/2-week trip evolved to somehow include Switzerland. Like most of our vacations, you could fit my priorities into one day, at least until I discovered Cargèse.

I'm usually all about churches when we travel. If I pick a destination, it probably has something to do with church. When we went to Alaska, I wanted to visit Aleut Orthodox churches and cemeteries. When we went to SoCal, it's my fault that we drove to Los Angeles to visit a Spanish mission. When we went to the U.K., I picked Durham cathedral, Iona (the oldest monastery), Kilninian (the newest monastery), and an infamous hike to the Nuns' Cave. (OK, that all took three days, and probably should have taken four.) Even when we're not visiting church as a destination, I'm usually the one who wants to attend a service somewhere I've never been before. I figured Corsica would be mostly Catholic churches, but I got the idea just to check if there was anything Orthodox or Byzantine--and that's how we ended up in Cargèse on Sunday.

In the later 17th century, the Republic of Venice lost Crete, its last major Greek holding in the Mediterranean, to the Ottoman Empire. In the aftermath a group of settlers from the Mani peninsula, at the southern tip of mainland Greece, arranged with Genoa to form a colony on Corsica. Their status as newcomers and their loyalty to Genoese authority did not endear them to the native Corsicans. It did, however, help to preserve their cultural identity for centuries to come. When most of the island won independence in the early 18th c., the Greeks retreated to the capital, Ajaccio, which was still held by the Genoese. When the island subsequently came under French rule, some of them sailed off to Florida, while others moved back up the coast to Cargèse. Conflicts with their Corsican neighbors continued for another 50 years, but they also intermarried, and the population of the town became mixed. The last native Greek speakers died out in the middle of the 20th c.

In order to settle on Corsica, the colonists had to become Catholic, but they were allowed to keep their Eastern rites. As the demographic makeup of the town shifted, the strain of sharing facilities led to the construction of two churches in the 19th c.--one Greek, one Latin--on opposite sides of a small valley. More recently, they have been staffed by one priest--currently a Melkite Catholic, Fr. Antoine Forget--with liturgies on alternate Sundays. This week mass was served in the Latin church, which we attended first.

The acoustics were beautiful, and the frescoes looked like westernized Byzantine scenes.

Later we walked over to the Greek church across a small valley.

The iconostasis had more westernized images, but the walls were covered in frescoes commissioned in the traditional Byzantine style in the late 20th c.

In the back of the nave, there was an interesting depiction of Satan holding humanity captive before Christ’s victory.

I would have loved to experience the Greek liturgy, but it was nice to explore both churches all the same.

0 notes

Text

Nonza

Julie and I share in common that our patron saints are both martyrs. And now we can add that we've made a best effort to visit the site where each died.

Peter the Aleut is much more recent but little-known. He's commemorated on two different days, depending on which Orthodox jurisdiction you follow, and there are at least two sites proposed for his martyrdom. In 2017 we visited Mission San Gabriel in Los Angeles (before it was gutted by fire in 2020), which I think is the more likely option. (Apologies to the San Francisco Orthodox crowd, who apparently are convinced it was in their backyard--I'll try to be an equal opportunity pilgrim at some point in the future.)

St. Julia was a first-millennium Christian from Carthage, taken as a slave aboard a merchant ship from Antioch, and crucified at Nonza on the island of Corsica. She is one of its local patrons, and you can still find a church and sacred spring dedicated in her honor. This week we were privileged to visit both. (Now we just need to get to Palestine for the kids' saints.)

The painting behind the altar depicts her martyrdom.

I couldn’t find out where they keep her relics in the church—maybe in here or locked away somewhere else?

It’s a fairly short but steep trail down to the spring.

Unfortunately at this season it was dry, but they put out jars of water so we could still take some home.

0 notes

Text

watches

Some years ago I started thinking about watches. I had in mind to get a wristwatch, which hasn't seemed exactly necessary for several years now (what with carrying a network-connected phone pretty much all the time) but still has some value. When I'm doing something active like riding a bike or gardening, it's not always convenient to carry or pull out a phone to check the time. And even when it is convenient, it's arguably better not to. I've caught myself frequently wondering what time it is, pulling out my phone to check, seeing an alert and stopping to check various messages, putting my phone away a few minutes later, and realizing I never actually paid attention to what time it was. So having a watch could help to minimize the time I spend looking at my phone, which can only be a good thing.

Anyway, I figured if I was going to invest in a watch, it should be something that would last, that could be repaired, and made as locally as possible. The problem being, of course, that watchmaking is one of those industries we decided in the course of the 20th century not to bother with. There has been a bit of a revival in recent years (and even more options available today than when I started thinking about watches), but most of what you can find made in America is going to cost anywhere from about five hundred to several thousand dollars. So I thought to go vintage and landed on Hamilton, which used to be made just a couple of hours away from here in Pennsylvania. They're now owned by Swatch and made in Switzerland, but back when they churned out hundreds of thousands of watches for American soldiers in WWII, it was all home-grown. And my taste is more the rugged field watch that a G.I. might have sported than the dressier watches they also made, so that's where I focused my attention. But I got tired of not finding exactly what I wanted in the right price range on eBay, and it quietly moved to the back burner for several years.

As we've been planning a trip to Europe (which was supposed to happen this year, but what with the pandemic and all, we're shooting for next year instead), I started to think that maybe a Swiss watch would be a good souvenir to bring back. But the price range is about what you'd find for American made, and I really have to hesitate about wearing something so valuable, especially if the main point is to wear it when I'm being more active and reasonably might do something that would damage it, or need to take it off and leave it somewhere. So I went back to my original plan and actually got as far as buying a Hamilton WWII field watch for about $200. Unfortunately, the accuracy was kind of poor, and after some back and forth with the seller, he said it was probably messed up in shipping and recommended that I return it for a refund. Which got me rethinking everything about buying a watch, because if I'm buying vintage without knowing how well it's been maintained, I'll probably have to factor in getting it serviced right away as part of the up-front cost.

And then I thought, do I really want to pay probably $100 or more every few years to maintain an old watch that probably wasn't the highest quality in the first place? I certainly don't have the steady hand or eye to go messing with my own adjustments. And I don't even know if there's a good watchmaker in the area that I could trust. Maybe I should just give up on the idea of getting something that can be repaired. I might be better off with a well-made Japanese quartz watch that needs an occasional battery change but otherwise just keeps really good time for a decade or two. And then I discovered that you can also find some reliable, reasonably inexpensive mechanical watches from Japan that are usually repairable to boot.

So I came up with a new set of criteria: price around $200 or less, made in Japan, durable, and reasonably accurate. Now, I've explained the process that got me here, but let's stop for a gut check. I started with some pretty high standards, and as I often find, the sticking point was price. But in this case it's not just a matter of being generally cheap (which I am); it's that my main reason for wanting a watch naturally constrains how much I'm wiling to invest in one. And I've also had to be more realistic about watch maintenance. As much as I hate to throw things away needlessly, it's neither cheap nor easy to get repairs when I need them.

As for the local piece, I've had to give a lot of ground there. For better or worse, American-made watches at this point are luxury items, and that's not likely to change soon. Even with more boutique watchmakers popping up, they're targeting people who want to make a statement, and there likely isn't enough market for basic, mass-produced watches made locally. So for my price range, I have to look at imports. And Japanese watchmaking, while it lacks some of the prestige of Swiss, is an established industry with its own innovations. So I still see it as significantly preferable to globalized outsourcing just to get the cheapest labor possible.

I should comment briefly on Swatch, which revolutionized Swiss watchmaking and today owns more of the market than anyone else. I could get a mechanical Swatch within my price range, but they are notoriously disposable and nearly impossible to repair. That seems to me like a poor design choice, and I tend to prefer a more classic look than they typically offer anyway.

So, this got me to two main contenders: the Citizen Chandler with Eco-Drive and the Seiko 5 Automatic. The Citizen is a solar-powered quartz watch, so you never change the battery. It runs a bit cheaper than the Seiko, but it gets really good reviews and keeps significantly more accurate time. It could last a decade or more but probably isn't worth repairing. The Seiko 5 is a well-known product line, which you can find either made in Japan or outsourced to Malaysia. It's not the most accurate mechanical watch you can find, but it tends to be a pretty solid performer for the price. And it can generally be repaired, with the potential to last several decades under proper maintenance.

Each has its advantages, but I ended up deciding that I really wanted a mechanical watch if I could get decent accuracy out of it. I like the non-electric design, and I feel a little more comfortable with the standard technology of an automatic watch over a solar-charged battery. And maybe it won't be worth repairing, but I like having the option. So far, it seems to have been a good decision. The Seiko feels pretty durable, stays wound with my normal level of activity, and keeps decent time for a fairly inexpensive mechanical. It's a little large for my wrist, but the numbers are very easy to read, and the glow feature works well in the dark.

0 notes

Text

O Light That Knew No Dawn

The fourth-century saint Gregory the Theologian (generally known in the West as Gregory of Nazianzus, but not to be confused with his father of the same name) is best known for his theological writings on the Trinity. He also wrote a great deal of poetry, including one titled σὲ τὸν ἄφθιτον μονάρχην, translated as "Hear Us Now, Eternal Monarch."

In the late 19th century, Scottish pastor John Brownlie adapted the last portion into an English hymn--"O Light That Knew No Dawn." The hymn appeared shortly thereafter in an Anglican hymnal, and persists to this day in Presbyterian hymnals, though set to a different 19th-century tune. In the past decade, it has seen at least two contemporary renditions:

youtube

The second version takes a bit more liberty with the lyrics, but is still recognizably the same text:

youtube

Brownlie consciously followed the example of Anglican priest John Mason Neale, who produced his own collection of translated Eastern hymns about half a century earlier. Although there has been dramatic improvement of Eastern liturgical translation in recent decades, I don't know of any other effort to render the texts poetically for a Western ear.

Now, don't get me wrong. I love Byzantine chant as much as anyone, and I'm more than comfortable singing texts that don't rhyme. But I also love to see poetry translated as poetry, and I really wish we'd made more progress in the past 150 years than these three small books by two long-dead writers. (There's also one called Hymns of the Russian Church, but some of the material is repeated, and the rest is harder to match with sources.) I'm glad to see at least that there has been some effort to revive this song, and maybe a few others, for 21st-century congregations.

Probably a minority of the hymns that Neale and Brownlie translated were ever set to specific music in the first place, so there's plenty more to work with if anyone's interested. And if the supply ever runs short, there's a whole career to be made for those with a poetic ear to adapt existing translations.

0 notes

Text

tea

I don't like tea, but it's cold, and I'm fasting, and my mother-in-law liked tea, so I'm drinking tea and remembering her.

None of us like tea, but we always kept a big box of assorted teas for when moms came to visit.

Then cancer took my mom, and my mother-in-law went into a nursing home, because her body was broken but her mind couldn't handle physical therapy, and her mind was broken but her body couldn't handle electro-convulsive therapy.

She was still her mostly happy self and always loved to see us, but she couldn't come visit anymore, so the tea just sat there in a cupboard. Then she died last year from COVID, despite their best efforts to guard against the disease.

My father-in-law used to visit her every day, but for months he could only see her on video calls. Eventually an asymptomatic staff member brought in the virus unaware, and it burned through the resident population.

She went quickly, but not all that peacefully. She died alone, and we buried her in a private family service. A week later they got the vaccine.

I'm happy for those who survived, but it's cold, and I'm fasting, and my mother-in-law liked tea, so I'm drinking tea and remembering her.

0 notes

Text

Memento mori

Here at the mid-point of the Dormition Fast, I have to say that I never quite know what to do with this one. Lent rolls along nicely on its own, and I've accumulated enough habits over the years for the Nativity Fast. But here we have a strict fast, just two weeks, and always interrupted by the Transfiguration. There's not even much pay-off. Usually you expect a significant fast to end in a significant celebration, and this one ends with (checks notes) a funeral?

Now, I get that we believe (even if we don't dogmatize) that her body was assumed into heaven. I even learned last year that our Latin brothers have some question as to whether she died at all. So there's a resurrection theme here, however you slice it. And as she was the first to make her body a temple of Christ, she was also the first to ascend in his care. So we take hope that we might follow in her footsteps one day. And yes, that's worth celebrating. But still . . .

I keep the practice of praying the Paraklesis throughout; what more? Well, this year I'm trying to think about death. If the fast ends in a funeral, then what better way to spend it than considering, what if it were my own funeral approaching now in less than a week? Am I ready? Hymns of Paradise, by Fr. Apostolos Hill, has long been my go-to recording of Orthodox funeral hymns. I've also been messing around lately with some English poetic versions of Orthodox hymns, which as far as I can tell were produced in the 19th century by two intrepid translators and never since. Some of them even made their way into mainstream English hymnals, though none from the funeral service:

Idiomela of St. John Damascene

Stichera of the Last Kiss

Stichera of the Last Kiss (Cento)

Stichera of the Last Kiss (Excerpt)

0 notes

Text

where do churches come from?

A schism, most simply, is a division. In church parlance, it refers to one group separating from another. Considered theologically, it is often framed in such a way that there is One Church, and a schism always entails some group separating itself from that Church. A schism can be driven by heresy--a difference of conviction--but it is always political.

When we talk about church history, certain schisms tend to stand out. In the fifth century, there were schisms that separated the Church of the East and the various non-Chalcedonian communions (Coptic, Armenian, etc.) from what we might loosely call the Catholic Church, or the Church of the Roman Empire. In the 11th century, there was the famous schism between what became known as the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. And in the 16th century, there was the Protestant Reformation, which expressed itself in a series of schisms from the Catholic Church. Schism is often how separate "churches" form (I've already written about our problematic way of talking about such things), but it doesn't always go that far. A schism is a bit like an Ecumenical Council, in the sense that you don't necessarily know what kind you're dealing with until well after the fact. In this regard, it might help to consider two notable schisms currently ongoing within the Eastern Orthodox Church--one that probably won't amount to much, and one that could.

The first schism is between the Patriarchs of Antioch and Jerusalem. For several years now, they've been in a jurisdictional dispute about who has canonical authority over the Persian Gulf region. It involves a rather small number of faithful in a territory that has not had much Orthodox presence for many centuries. The Patriarchs don't commemorate each other and don't celebrate communion together, but that's about as far as it goes. It's meant as an expression that something is not right between them, and rather than brush their problems under the rug and act like everything's fine, they'll refrain from these symbols of unity until their issues can be resolved. But a layperson of the Antiochian jurisdiction can receive communion in Jerusalem, and even a priest or deacon can serve in the altar. I would guess that most of the faithful don't even know the schism exists. And this is probably typical of most schisms in their beginnings.

The second schism is between the Patriarchs of Constantinople and Moscow. It expresses a division that has been growing over decades, but it didn't formally start until 2018. Both claimed jurisdiction over the Orthodox Church in Ukraine but took different approaches to resolving its internal problems. The result was an establishment of parallel churches--one autonomous under Moscow, the other autocephalous (fully independent). Moscow views Ukraine as integral to the historic identity of the Russian Church, and its response was to withdraw from communion with Constantinople and pretty much anyone else who supported the autocephalous church structure it set up in Ukraine. And that goes all the way down to banning its priests, deacons, and laypeople from intercommunion, which is decidedly atypical. While there is no real issue of heresy per se, there are some pretty serious differences, and both sides seem quite entrenched. Given the organizational weakness of the Orthodox Church, I think it could evolve into a more permanent schism if left to run its course.

Now, what these two schisms have in common (at least for now) is that they are decidedly treated as schisms within the Orthodox Church. Even given the severity of the schism over Ukraine, no one else is participating. As far as I know, no other local Orthodox Church has broken communion with either side, and even Constantinople, for its part, has not broken communion with Moscow. So an Orthodox layperson under the Antiochian jurisdiction, for instance, can still receive communion in any other Orthodox church. Their clergy can concelebrate with Russian or Greek--just not both at the same time. So we would say definitively that the schism makes no theological difference--neither Constantinople nor Moscow has somehow left the One Church by virtue of being out of communion with the other.

Now, how does this relate to past schisms? What happened in 1054 was specifically a mutual excommunication of persons. Rome excommunicated the Patriarch of Constantinople, who in turn excommunicated the papal legates--significant actions to be sure, but probably not readily obvious as the start of some permanent reconfiguration. It was likely another 150 years before the laity were specifically forbidden from receiving communion across the aisle, so to speak, and that only in the wake of the Fourth Crusade, when the Latins seized Constantinople itself and set up their own churches in parallel with those of the East. Whatever differences of faith and practice may have existed before and after 1054, it was fundamentally the political climate that determined where one could receive the grace of the Church, not any clear spiritual boundary line.

We can talk in various ways about someone as being either Catholic or Orthodox, so long as we recognize what we're really saying. If the Orthodox Church is understood historically as the church of the Byzantine Empire, then a person born, raised, and living in Constantinople in the 12th century was probably Orthodox. But what if he moved to Rome? Would that suddenly make him Catholic? What would have to happen to change his identity? And is this just a historical question? Would our Byzantine abroad even have thought about it as a spiritual distinction?

Or what about a Latin soldier who came east with the Fourth Crusade, took part in the attack on Constantinople when he thought it was just to restore the rightful heir to the throne, but later sympathized with the Byzantines and chose to attend one of their churches? Was there a process for him to "convert"? Would such a thing even have occurred to anyone? Would it have been possible at that point in history?

Or what about today? If I was born and raised Protestant but "converted" as an adult to the Orthodox Church, what is my relationship to Rome? Am I supposed to have been Catholic all along? Am I somehow Western by birth but Eastern by choice? If I chose to become Catholic, I would be accepted by a simple profession of faith because I'm Orthodox. Would I then be Melkite Catholic so as to preserve my Eastern heritage? I'm an American convert from an American convert parish--what is the real significance of my Arab patrimony?

And speaking of which, what about the 18th century schism among the Arab Melkite Christians? Those who accepted Western support against Ottoman oppression became Catholic, while those who aligned with the Greek establishment in Constantinople were called Orthodox. Three centuries later, where is the substantive difference in their faith or practice? That one is theoretically in communion with all other Catholics and the other with all other Orthodox? That family allegiance marks them as one or the other? Where does this distinction put them with regard to the One Church?

So if we come at the question historically, I think it becomes difficult to rigidly identify the One (Holy, Catholic, Apostolic) Church with a specific institution. Divisions arise for many different reasons, and their interpretation depends on many different factors. Yes, everyone generally agrees right now to talk about Russian, Greek, Romanian, and Serbian Orthodox as all part of one Eastern Orthodox Church, and Roman, Ukrainian, and Melkite Catholic as all part of one Catholic Church. But the alignments and disputes over the centuries that have contributed to this picture seem to require only small nudges one way or another to have produced different results. Assigning theological weight to such historical details seems contrived.

And what makes matters worse is the force of inertia that seems to resist most efforts at reconciliation. After 15 centuries of separation, quite a few theologians have concluded that the doctrinal bases for schism between Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian Orthodox were minimal or non-existent. Political motivations have shifted to the point that it's probably in their interest to restore communion, but that's a lot of historical identity to overcome. On the other end of things, the two sides in the comparatively recent Melkite schism have almost everything in common and seem quite open to some sort of restoration; but relations with the broader Catholic and Orthodox Churches make it difficult to progress on the local level. And however promising overtures toward Catholic and Orthodox reconciliation might seem, it's difficult to envision a scenario that wouldn't split each Orthodox church down the middle and just exacerbate the divisions. Such reticence is understandable, I suppose, and only human--but as a basis for theological claims about where the One Church might reside, it seems pretty flimsy.

So all of this has me taking my identity as Eastern Orthodox much less seriously than I used to. Not that I feel inclined to give it up--I just don't know where the boundaries are, or even if I care. I've always known that these terms we use--One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic, even Orthodox--are generically applicable to the claims of other apostolic churches (Catholic, Coptic, Armenian, etc.); but the reality seems similarly messy. We can't reduce it to One Church, excluding all else, or to various churches as branches of a whole. For me, it helps to think in terms of schisms, as they evolve through different historical moments and perceptions and prejudices and identities. If these divisions depended on human choices and actions in their formation, who's to say we couldn't end them just by changing our minds?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

on catholic churches, and other things that don't exactly exist

I've been mulling this over for a while now, and I'm not even going to pretend that it has any claim to theological validity--it's just my own reflection on how I see things.

We affirm quite often--weekly, if not daily--a belief in one holy, catholic, apostolic church. And when I say "we," I mean pretty much anyone who consciously follows the Nicene Creed. Now, there are Protestant ways of dealing with this language, which don't really interest me right now, but as I understand it there's a reasonable consensus between Catholics and Orthodox. The simplistic version is that there is One Church, which is both an institutional and a spiritual reality, which is the thing that we think of when we say "the Catholic Church" or "the Orthodox Church"; and everything outside that Church, whatever it might call itself, is something else.

But then we get into questions like, are there real sacraments outside of this One Church, which again, we can simplistically say "no" and thus invalidate whatever those people over there are doing. Or if there are real sacraments elsewhere, they must somehow belong to the One Church and only appear to be performed by those other things, whatever they are.

Or we might ask what it means to move from one Christian tradition to another. Is it conversion, in the sense of moving from one faith or religion to another, or is it something else? And is there really a there there, which is to say, how do you even move from one thing to another if one is not real, and the other is all there is?

And all of this is further complicated by the fact that we're trying to play nice, and so we call things churches when maybe we don't really believe what we're saying, or at least we don't think they're the One Church like this other church over here. And maybe the real problem is that Church (in the theological, spiritual sense) isn't even a thing that can be thought of as plural at all.

So where I think we often end up is affirming with our words the universality of the One Church and assuming that One Church is our church, but then acting like it's really a denomination among many. We settle for the claim that this church is The True Church, and all those other things aren't. And thus we welcome converts as if they're really coming from outside the Church into it, and we say that our sacraments are valid and theirs are not, and we reduce our lofty theological claims to jurisdictional chauvinism.

Here's my point: if the Church is One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic, then we can't think of it like a one-party state where everyone votes to keep up the façade of democracy but already knows the outcome; we have to treat it as the universal, all-encompassing body that we imagine it to be. And that means that it is the One Church for those people out there as much as for those of us in here. This One Church does not exclude; on the contrary, it includes everyone, whether they want it or not. That may not sound especially appealing to those who want nothing to do with the Church, but I'm not arguing here to convince them that they belong; I'm talking to those of us who think we already do.

Let me try a specific example. It is common practice in both the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church to receive already-baptized (typically Protestant) "converts" through the sacrament of confirmation/chrismation (two different names for essentially the same thing). Now I'm not sure how this is handled among all the various Orthodox churches; but in the Catholic understanding, Orthodox chrismation is treated as a valid sacrament, and thus an Orthodox Christian who wants to become Catholic is received through a simple profession of faith--no sacrament required. This includes a case where someone was baptized Protestant, chrismated Orthodox, and then becomes Catholic. I believe the Catholic Church would also say that their Protestant baptism was truly valid, which is not always how Orthodox interpret it, even if they don't require baptism upon "conversion."

So is this rite of chrismation or confirmation really about bringing them into the Church, in the sense that they were formerly somewhere else and now we're letting them through the door, or is it about completing what was lacking in their formation so that they can participate fully in the sacramental life of the Church? Yes, it could be both; but my point is that we probably misunderstand what's really happening if we think of it as bringing them from one spiritual territory to another. To come at the question a bit differently, a Roman Catholic child who goes through the usual progression is baptized, then receives first communion, then goes through confirmation some years later. (Eastern practice usually combines all three, so for this example the Latin way is more useful.) Prior to confirmation, are they really thought of as outside the Church, such that they have to be brought in through a special sacrament? What if their family drifts away and stops attending before they reach confirmation? If they complete the process much later as an adult, are they considered a "convert"? There's probably a canonical answer here, but I wouldn't think that's the right understanding. It's just a matter of completing the process that was begun.

So if we think of a Protestant the same way--they were baptized in accordance with their Trinitarian faith, and no one ever bothered to take it further. But whether they knew it or not, the grace given through the Church was at work. If someday they receive chrismation in the Orthodox or Catholic Church, they will do so not as a stamp of approval that they are now part of the True Church (whichever one that is), but because the Church offers her children the sacraments for their spiritual life, and this is the next step along the path to full communion. Yes, it can function practically as a formal step of transition, but it does not bring them inside the Church, because they were never outside in the first place. They were children lacking in certain stages of development that are now being filled up.

Now the paradox is that this works both ways. A baptized Protestant can be chrismated Orthodox and later welcomed into the Catholic Church without any sacrament of entrance, or they can be confirmed Catholic and later welcomed into the Orthodox Church (presumably, at least in certain cases) without a further sacrament. So in a sense, Catholic confirmation can bring someone into the Orthodox Church, or Orthodox chrismation can bring someone into the Catholic Church. Of course, we can't erase the distinctions between the two, but somehow the sacraments are permitted to operate the same regardless.

What, then, does it really mean--in a spiritual or theological sense--for there to be these two things that call themselves (One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic) Church? They can't be two Churches (not really), but neither are they branches of the One Church. It seems to me too simplistic and crude to just claim that one is real and the other is not. And what does it mean that the sacraments can be of the One Church but not limited to what happens within one organization? I think the answer is probably somewhere in this idea of catholicity--of universality--where whatever the Church is, it is that without limit or boundary. This doesn't mean that all things called churches are one or the same or parts of a whole. I think it's probably closer to the idea that the Church exists and operates everywhere, with regard to everyone, whether they know it or not. But that still leaves unanswered questions: How do you have separate communions (I've been talking here about two, but there are others that could be considered in the mix) but only One Church? And how exactly does the institutional Church correspond with the spiritual? I don't have any clear answers, and this post is already long enough. But I do have a few more thoughts for another day.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Still My Maryland, but . . .

Twelve years ago, I wrote my state delegates urging them to vote against a bill proposed to change the Maryland state song. In vain defense, I had only discovered the song a year before, and at a time when I was just learning how to love local. I still believe that my adopted home state suffers from a lack of identity, especially here in the mass of suburbs between Washington and Baltimore. I still believe that such a song is the kind of kick it needs to remember itself. I still doubt that we will ever come up with a worthy replacement. But looking back on my initial reflections, I see some arguments I would not make again. And not without a twinge of sadness, I have to agree it's time for the song to go.

I still believe that the American Civil war was more complicated than we generally allow in popular imagination. Abolitionists may have been on the side of the North, but the North was not always on the side of abolition. Like so many other great changes in history, slavery ended not because it was the right thing to do (though it was), but because powerful men decided it served their interests to make it so. I celebrate that outcome, but not every outcome, and not every motive or method that brought it about. And as a child of the North, I think it is my primary duty to confront the evil that marched in "our" ranks. But that doesn't mean I have to whitewash the South or its motives.

As for Maryland, I still think the song gives it an important voice. Set before the real action of the War, it emphasizes the tyranny that was already descending, simply because of where it was located. A free Maryland was a strategic liability for Washington, and I cannot help but see its forcible annexation to the Union side as a precursor of its suburban status today.

But looking at the War in hindsight, the Northern victory and the resulting liberation of slaves overshadows all. In one sense it should, though the historian in me wants to argue for a more nuanced reading. The Free State had to lose something important for that desirable end, and I want to mourn what was lost, even if the sacrifice was worth it. Still, I cannot deny that the song now strikes a sympathetic note with the cause of the South that can only hurt many of my fellow Marylanders. Yesterday the Governor signed a bill repealing the state song, and I will bear it "bravely meek."

1 note

·

View note

Text

Forgiveness

Last year about this time the pandemic hit, and churches were closed for much of Great Lent. Before that happened, we did get to kick things off with the usual observance of Forgiveness Vespers. At the end of the service, everyone lined up in a big double horseshoe. In a sort of dance, we would bow, forgive, kiss, and move to the right, until everyone present had stood before everyone else. In this way we would begin the 40-day struggle of Great Lent having reconciled our human relationships and ready to support one another.

Little did we know that we would soon be separated from each other like the monks in St. Mary of Egypt, scattered in the desert to find our own way. And unlike those monks, our separation would last beyond Pascha (Easter). It was a real, earthly struggle, of the sort that doesn't fit our liturgical schedules--indeed, in many important ways, it's still ongoing a year later, as we approach the start of another Great Lent and another Forgiveness Vespers.

(Orthodox churches follow the old Julian reckoning for Easter, Lent, and the rest of the "movable" calendar. This year, that puts us about a month behind the West. If you want to know more, take a deep breath and read this post from my older blog.)