#you deserve to be assaulted and left for dead in an alley except not dying just suffering immensely forever and ever

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

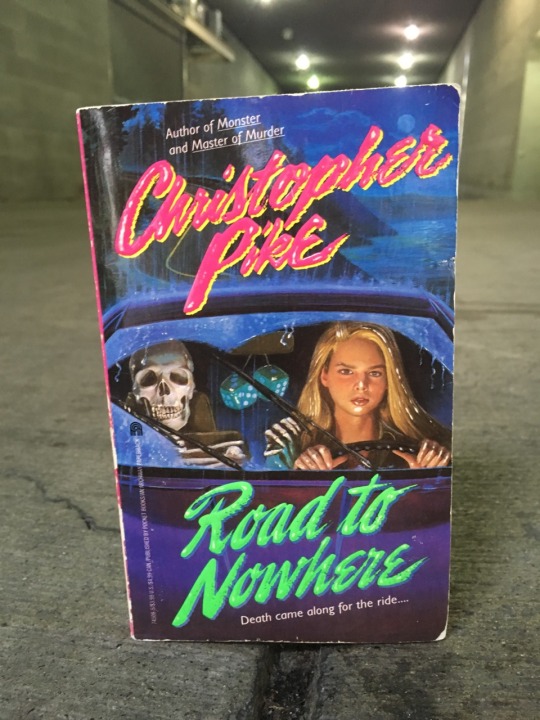

Road to Nowhere

Pocket Books, 1993 212 pages, 14 chapters + epilogue ISBN 0-671-74508-5 LOC: CPB Box no. 700 vol. 15 OCLC: 27485847 Released February 1, 1993 (per B&N)

Scorned by her parents, spurned by her boyfriend, shoved aside by her best friend, Teresa Chafey is on the run. She hops in her car and heads into the night with only the vaguest of destinations: north. Before she gets too far, she picks up a pair of hitchhikers, and they exchange stories of life’s unfair endings as they drive. But as Teresa drives, she gets sicker, and she learns more about the two strangers in her car and how they got there, and she begins to realize that there’s one big ending awaiting her unless she can forgive and move on.

I didn’t remember much about this story from my early reads, but I do remember liking it. It’s interesting that I never came back to this one very much, because it does seem to be right up my alley: minimal characters, single point of view, realistic settings, just a hair of the supernatural. I also greatly appreciate on re-read how the whole thing takes place in Teresa’s dream state. Yeah, this is a cliche, but the structure holds up. Some of these “it was all a dream” type books don’t have enough weight in the narrative to get by without a lot of explanation either before or after, but Road to Nowhere gives us what we need in the middle. And a big part of that is the storytelling mechanic employed by the characters.

It would be easy to have a story about telling stories feel a little dry and inorganic (and as I recall, we’ll get there soon enough), but because these stories are autobiographical (yes, it’s obvious that the hitchers are talking about themselves, even though they’ve assumed names) it feels important and natural. A contributing factor might be the in media res beginning, with Teresa storming out to her car and taking off before we even actually know what’s upsetting her. She picks up her hitchers, Freedom Jack and Poppy Corn (seriously), just before the freeway on-ramp, and each spins a story of lost love and life lessons.

Rather than break this down chapter by chapter, I’m going to summarize each character’s stories. Lucky for you, reader, this format doesn’t lend to as long a post as I often subject you to.

I’ll start with Teresa, since it’s her fault we’re in this car in the first place. She’s also the only one to talk openly about herself. She describes meeting her boyfriend at the mall while Christmas shopping, and how he gets her talking about herself like she’s never really done with anyone else. In fact, he gets her to play guitar and sing for him when she is afraid to perform anything for anybody. We’re led to understand that this comes from her mom not thinking anything she does is ever good enough, and so she hides things from her parents, including this talent. But her boyfriend thinks she’s so good that he gets her in as a performer at a nightclub, and her best friend wants to come and see her too. Of course, while Teresa is up on stage she can’t supervise the budding relationship between her two companions, and they fall for each other. The last thing Teresa remembers before getting in the car and driving off was going to her boyfriend’s house with a knife and seeing the two in each other’s arms.

Free goes next. He describes a gifted yet hot-headed young man named John, who falls in love with a girl named Candy and helps her cheat her way through school. Unfortunately, he gets caught helping her, and rather than take his lumps and move on, he beats up the teacher and goes to juvenile hall. When he gets out, his college options have been wiped away, and so he takes a job in a bakery, where he comes up with efficient solutions to economize production. Unfortunately, his manager is a dick. Not only does he take credit for John’s optimization, but he also alters the machines so that when John is demonstrating a change he gets his hand caught and loses two fingers. There’s no way to prove it, but John is hell-bent on trying, and is too proud to take a settlement. But when the defense brings up his assault of the high school teacher, John flips out, to the point where there’s no way a decision will go his way. He’s stuck with a throbbing injury, a dependence on painkillers, and no real option for relief. Except robbery. He starts with pay phones and vending machines, but has to escalate to convenience stores. But of course the first job goes wrong when John sees Candy walk in. He’s shot and killed, but as he’s lying on the ground there’s another gunshot and Candy falls onto him, dying as well.

Poppy tells Candy’s side of the story. Like, this is the only place where the structure of this story falls apart — are we actually expected to believe that the stories Free and Poppy are telling are in any way not about themselves? It’s just so obvious. We could argue that it’s because I already know the story, but I’m not sure if that’s true. It’s been twenty years, at least, after all.

But so Candy’s story is about what happens after John leaves her life. She gets up to college and realizes she can’t hang, but she falls for a teacher and gets enough help to muddle through, at least for a little while. Of course, shit happens, the teacher gets her pregnant, and she decides to go away and have the baby, who she loves more than anything ever. It’s the kick in the ass Candy needs to figure out how to take care of herself. She does the crazy single mom thing of working and going to school both full-time while taking care of a baby, nails down a nursing degree, and moves back home so her parents can have a grandson while she works. But of course she’s got this nasty smoking habit that she can’t kick, and it’s while she’s stopping to pick up a carton of cigarettes that she finds John, the only man she’s ever loved, robbing the store.

The whole time, Teresa is feeling sicker and sicker. Her wrist hurts, her hands are clammy, she’s got a headache, and her throat is dry. Also, the road isn’t really taking them through the region she expected, and none of the towns are where she thinks they should be. They do stop a few times, at her passengers’ insistence: once at the house of a mystic fortune teller (who Free calls his mother) who tells Teresa she’s afraid of love and just wants attention (which is maybe why she gives up the booty to Free in a back room) and once at a church where a priest (Poppy’s father) is trying to help Teresa remember the blank space between her boyfriend’s house and her car. They also hit several convenience stores for snacks and beer — but the last time, Free pulls a gun and starts robbing the place. A young nurse walks in, and he tells Teresa to hold her at bay with the knife in her back pocket. The knife Teresa didn’t remember. The knife she didn’t feel until that very moment. The knife that slips and cuts the nurse’s throat when Free shoots the clerk in the face.

As if this wasn’t disconcerting enough, the next stop is a familiar-looking apartment complex; specifically, a familiar-looking apartment where the bathroom door is closed and the water is running. Free pulls a video tape out of thin air and sticks it in the VCR, and it shows Teresa climbing into her car and driving away. And then he rewinds it, to Teresa in the bathtub, cutting her wrist open with the knife she found in her back pocket.

So we finally start to see what’s going on. Teresa is dying, and Free and Poppy are the dead souls of John and Candy, one devil and one angel, fighting over her soul. Only Poppy has an ulterior motive. She’s come along on this journey to show John that he wasn’t so bad, and that he doesn’t deserve his torment. See, he’s struggled with the understanding that in his last moments of life, he flexed his fingers and fired the bullet that killed Candy. But he didn’t. She tells him that it was the police officer, trying to take him down but misfiring and hitting her. In fact, this has been her message the whole night: tell the truth, act with love, and forgive the past. If she can get Teresa to do that, she can still be saved.

Like, literally: all of a sudden Teresa’s spirit skips to the fire in her boyfriend’s house, and she sees the philandering pair on the rug in front of it, and she’s ready to forgive them. And as the anger flies away, a log in the coals pops and shoots a spark onto her boyfriend’s arm, waking him up. He looks around, bewildered, and sees Teresa’s key in the door, where she left it in her rage. And before he can even puzzle things out, he knows she’s in trouble and takes off to help her.

Our epilogue (which Pike seems to have figured out the workings of, suddenly) finds Teresa waking up in the hospital, watched over by a young pre-med student. He tells her that her boyfriend found her and brought her in, and that there are four people waiting to see her. She talks about her anger and her sadness, and they commiserate together, and all of a sudden she realizes that he is Candy’s young son, left behind when she died in a robbery. And that’s it.

I find it interesting to think about how Pike’s juggling interests in different religions and traditions while he writes these vaguely mystical works. There’s some very clear Catholic background in a lot of these works, but he’s also working in his interest in Buddhism and Hinduism and other Eastern traditions. It’s not a solution that works for everyone, but the idea of giving up the things that make your blood boil and forgiving people who wrong you to take the next step toward enlightenment does have a lot of basis in religion. As long as we acknowledge this baseline, Road to Nowhere works as a story. It’s not a book we should base our belief system on or anything, but it hangs together for Teresa.

1 note

·

View note