#witsen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Amsterdam view of the Herengracht - Willem Arnold Witsen , 1901.

Dutch , 1860-1923

Watercolour on paper , 54.1 x 71.8 cm.

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

Willem Witsen (1860-1923), Winter landscape

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Leidsegracht te Amsterdam’ by Willem Witsen (1860-1923)

#willem witsen#vintage art#classic art#art#art history#old art#art details#vintage#moody art#etching

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

willem - graphite | 20 x 12

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Voorstraatshaven, Dordrecht". 1900.

By Willem Arnold Witsen. Dutch. 1860-1923.

> random-brushstrokes

0 notes

Text

NL-4K-J

Joseph Jesserun de Mesquita (1865-1890, Amsterdam) werd maar 25 jaar en toch was zijn invloed op zijn tijdgenoten groot. Joseph fotografeerde vooral. Niet zoals toen gebruikelijk geregisseerd en geënsceneerd, maar losser. Het vasteleggen van een bestaand moment, zoals deze groepsfoto waarop we tijdgenoten en kunstenaars Willem Witsen, Willem Kloos, Hein Boeken en Maurits van der Valk zien. Die…

View On WordPress

#19-de en 20-ste eeuws#Amsterdam#Artis#bedrukken#belangstelling#bestaand moment#Claude Monet#dierenportret#eenvoud#fotografie#fotografische schets#Hein Boeken#houtsnede#Impressionisten#invloed#Johan Bartold Jongkind#Joseph Messerun de Mesquita#Lattrop#losser#Maurits van der Valk#meubels#platteland#Romantiek#Samuel Jesserun de Mesquita#schilderkunst#stedelijke ontwikkeling#stof#vrijer#Willem Kloos#Willem Witsen

1 note

·

View note

Text

Toltec Shaman🌵 Keepers of spiritual knowledge and practices of the ancient masters

Our first recorded glimpse of what was to become known a shamanic practice, accessing the spiritual knowledge of all ages, labelled shamans (men) and shamankas (female) by anthropologists to define the role of the spiritual leaders and keepers of the knowledge in the 1400s in Siberia and Mongolia.

The word ‘shaman’: The root of the word means ‘to know‘ and may originate from ‘šamán‘, most likely from the Tungus language of Mongolia. The word was thought to be brought to the west in the 17th century by the Dutch traveller Nicolaas Witsen, who recounted his experiences with the Tungus-speaking people of Siberia in a book Noord en Oost Tartaryen, which was published in several languages.

Don Miguel Ruiz is one such modern shaman, who shares the ‘Toltec Spirit’ of the ancients, and the Toltecs of today, our modern shamans, are still spiritual warriors…

A modern movement led by writer Miguel Ruiz is called ‘Toltec Spirit’. In his famous book The Four Agreements, Ruiz outlines a plan for creating happiness in your life. Ruiz’s philosophy states that you should be diligent and principled in your personal life and try not to worry about things you cannot change.

No one knows why the Toltec culture disappeared sometime in the 12th century and, other than the name ‘Toltec’, this modern-day philosophy has absolutely nothing to do with the ancient Toltec civilisation.

From the Mastery of Love, by Miguel Ruiz:

“Thousands of years ago, the Toltec were known throughout

southern Mexico as “women and men of knowledge.”

Anthropologists have spoken of the Toltec as a nation or a race, but in fact, the Toltec were scientists and artists who formed a society to explore and conserve the spiritual knowledge and practices of the ancient ones. They came together as masters (Naguals) and students at Teotihuacan, the ancient city of pyramids outside Mexico City, known as the place where ‘Man becomes God.’

“Over the millennia, the Naguals were forced to conceal the ancestral wisdom and maintain its existence in obscurity. European conquest, coupled with rampant misuse of power by a few of the apprentices, made it necessary to shield the knowledge from those who were not prepared to use it wisely or who might intentionally misuse it for personal gain.

“Fortunately, the esoteric Toltec knowledge was embodied and passed on through generations by different lineages of Naguals. Though it remained veiled in secrecy for hundreds of years, ancient prophecies foretold the coming of an age when it would be necessary to return the wisdom to the people. Now, Don Miguel Ruiz, a Nagual from the Eagle Knight lineage, has been guided to share with us the powerful teachings of the Toltec.

“Toltec knowledge arises from the same essential unity of truth as all the sacred esoteric traditions found around the world. Though it is not a religion, it honours all the spiritual masters who have taught on the earth. While it does embrace spirit, it is most accurately described as a way of life, distinguished by the ready accessibility of happiness and love.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Willem Arnold Witsen - Amsterdam, Halvemaansteeg, corner Amstel in winter, etching.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

The earliest known depiction of a Siberian shaman, produced by the Dutch explorer Nicolaes Witsen, who authored an account of his travels among Samoyedic- and Tungusic-speaking peoples in 1692. Witsen labelled the illustration as a "Priest of the Devil" and gave this figure clawed feet to highlight his demonic qualities

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

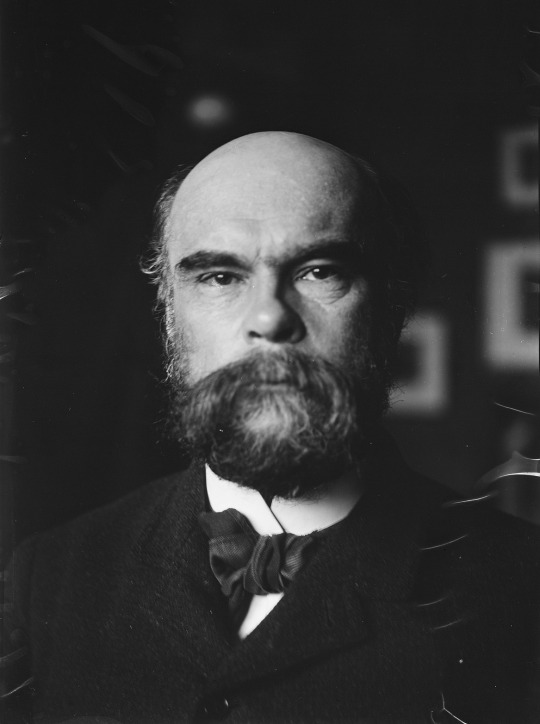

Paul Verlaine

Photographie par W. Witsen en 1892

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forest in the snow - Willem A. Witsen

Dutch, 1860-1923

Oil on canvas , 59.5 x 69.5 cm.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Willem Witsen (1860-1923), Voorstraathaven IV (Zonreflectie)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nový Amsterdam

NOVÉ HOLANDSKO

Vroege nederzetting - první pronikání (1609-1624) De eerste 15 jaar in het bestaan van de kolonie werd het eiland Manhattan slechts spaarzaam gebruikt door de Nederlanders. Prvních 15 let existence kolonie byl ostrov Manhattan Holanďany využíván střídmě. De kolonie was als steeds bedoeld als een winstgevende onderneming en niet als een middel om de Nederlandse cultuur over te brengen. Verder stroomopwaarts langs de Hudson lagen beverrijke en onontgonnen wouden Až zhruba do roku 1623 platilo v oblasti Nového Nizozemska právo jednotlivých lodí, až poté zde byly zavedeny zákony nizozemské. Pro osídlení byla nejprve vybrána oblast u ústí řeky Hudson, vhodná z důvodů klimatických, přístupu k oceánu a snadnému kontaktu s indiány, se kterými osadníci vedli čilý výměnný obchod – především s kožešinami. V těchto místech vznikaly nové osady, mj. zárodek nynějšího města Albany.

Eerste kolonisten (1624-1636) De passagiers werden spoedig verspreid: na ontscheping op het Noten Eylant (tegenwoordig Governors Island – setkání Gorbačov / Regan, Bush) bouwden ze een fort en windmolen op Noten Eylant. Na Ostrově guvernérů byla také vyhlášena provincie Nové Holandsko. V květnu 1624 připlula loď New Amsterdam, pronajatá Západoindickou společností, do Noten Eylant těsně pod ostrovem Manhattan. Kapitánem lodi Nieuw Nederlandt byl Cornelis Jacobsz. May, měl by také sloužit jako první guvernér kolonie. Na palubě lodi bylo asi třicet rodin ze Spojených sedmi provincií. Většina z nich byla původně jihoholandského nebo valonského původu (nyní Belgie) a holandsky mluvícího. V 16. století se přestěhovali na sever a na severu měli vlastní valonské kostely (např. Amsterdam, Haarlem, Leyden). Cestující byli brzy rozptýleni: po vylodění na Noten Eylant (nyní Governors Island) postavili pevnost a větrný mlýn na Noten Eylant.

Ze ontscheepten op de plaats waar nu de stad Albany ligt, de hoofdstad van de staat New York, en bouwden daar Fort Oranje (1624).

Vestingwerken Nebezpečí útoku kolonizátorů z jiných evropských zemí vedlo vedení Nizozemské západoindické společnosti k vytvoření plánu ochrany vzniklé oblasti. V roce 1625 byla většina osadníků přestěhována na Manhattan, kde Cryn Fredericks van Lobbrecht za řízení Willema Verhulsta vybudoval citadelu těsně nad jižním břehem ostrova. . Drie expedities volgden in de daarop volgende jaren, geleid door Adriaen Block, maar in 1614 leidde een fusie van vier Amsterdamse en een Hoornse Compagnie tot de oprichting van de Compagnie van Nieuw-Nederland. Tot de bewindhebbers behoorden Gerrit Jacobsz. Witsen en Lambert van Tweenhuysen. Toen in 1618 het vierjarig octrooi der Compagnie ten einde l

V té době vydělávaly bobří kůže v Evropě sužované velmi chladnými a dlouhotrvajícími zimami spoustu peněz; Kožešiny se používaly k výrobě nepromokavých klobouků. Vedlejším produktem obchodu bylo castoreum nebo bobří roh, který byl používán pro své předpokládané léčivé vlastnosti. In die tijd leverden beverhuiden veel geld op in Europa dat geplaagd werd door zeer koude en langdurige winters; de pelzen werden gebruikt voor het maken van waterdichte hoeden. Een bijproduct van de handel was castoreum of bevergeil dat gebruikt werd vanwege de veronderstelde geneeskrachtige eigenschappen

V následujících letech následovaly tři expedice vedené Adriaenem Blockem, ale v roce 1614 sloučení čtyř Amsterodamu a Hoornse Compagnie vedlo k vytvoření společnosti New Netherland.

Begin van Nieuw-Amsterdam - založen Nový Amsterdam (1626-1647), v první epoše jako město domů ze dřeva Legenda o úplatě Indiánů Německy: Dem Kauf folgte darüber hinaus eine mehrjährige Phase, in der die indianische Bevölkerung auf Kosten der Siedler bewirtet und mit Waren und Nahrungsmitteln versorgt werden musste.

Terwijl het fort gebouwd werd, leidde de groeiende oorlog tussen de Mohawks en de Mohicanen in het dal van de Hudson ertoe dat de West-Indische Compagnie de betrokken kolonisten ging verplaatsen naar de nabijheid van het nieuwe Fort Amsterdam. De dringende behoefte aan een vestingwerk, evenals het feit dat de kolonie als geheel geen winst maakte, leidde tot het versoberen van de oorspronkelijke plannen. In plaats van het originele metselwerkfort werd een eenvoudig blokhuis geconstrueerd, omringd door een palissade van hout en aarde. Een zaagmolen werd gebouwd op het huidige Governors Island.

Mezi výrazné osobnosti patřil například Peter Stuyvesant (1647-1653)

Stad Nieuw-Amsterdam (1653-1664) - Nový Amsterdam jako město z kamene

Bloei van de stad - rozkvět města Město vzkvétalo s příchodem městské vlády. Silnice byly vydlážděny oblázky, cihlové domy nahradily dřevěné, byly zavedeny střešní tašky a staré doškové střechy byly zakázány kvůli nebezpečí požáru. Za Paerl Straet byl postaven dvůr. Město se stalo úhledným s zametenými ulicemi a chodníky. Stromy ve městě byly esteticky prořezány a zahrady dostaly úhledný kosočtvercový, oválný nebo čtvercový tvar. Byla vydána vyhláška, která nařizovala zemědělcům trhat slepice a kurníky, pokud byly jasně viditelné ze silnice. Vlastníci s prázdnými pozemky na hlavních ulicích museli platit dodatečné daně, aby je povzbudili k tomu, aby s pozemky něco udělali. Příkop vykopaný v centru města byl po příkladu Amsterdamu modernizován na kanál, kompletně s dřevěnými podpěrami a krásnými kamennými mosty.

De stad bloeide door de komst van het stadsbestuur op. Wegen werden geplaveid met keitjes, bakstenen huizen vervingen houten exemplaren, er werden dakpannen ingevoerd en de oude rieten daken werden verboden wegens brandgevaar. Voorbij Paerl Straet werd een werf gebouwd. De stad werd netjes met aangeveegde straten en stoepjes. De bomen in de stad werden esthetisch gesnoeid en tuinen kregen een keurige diamant-, ovale of vierkante vorm. Er werd een verordening uitgevaardigd waarin stond dat boeren varkenskotten en kippenrennen moesten afbreken als ze duidelijk zichtbaar waren vanaf de weg. Eigenaren met lege stukken grond aan de hoofdstraten moesten extra belasting betalen om hen te stimuleren iets met de grond te doen. De sloot die door het centrum van de stad was gegraven werd opgewaardeerd tot een gracht naar Amsterdams voorbeeld, volledig met houten beschoeiing en fraaie stenen bruggen.

Anglická invaze

Op 24 september 1664 capituleerde directeur-generaal Peter Stuyvesant en droeg Nieuw-Amsterdam over aan de Engelsen. Stuyvesant drong aan op garanties voor de rechten van de burgers, die terechtkwam in de zogenaamde Articles of Capitulation, Artikelen van Overgave. 2.8 Herovering door de Republiek en definitieve overdracht

Herovering door de Republiek en definitieve overdracht

Na ondertekening van het Verdrag van Westminster op 19 februari 1674 werd de kolonie Nieuw-Nederland met de stad Nieuw-Amsterdam (New York) voorgoed overgedragen aan de Engelsen.

In navolging van de Glorious Revolution (de bestijging van de Engelse troon door de Nederlandse stadhouder Willem III), wilde Jacob Leisler, een oude Nieuw-Amsterdammer, de kolonie voor Nederland in 1689 heroveren met een opstand. Willem III voelde hier echter niets voor en de Opstand van Leisler, zoals die de geschiedenis in ging, liep met een sisser af. Leisler en kompanen werden opgehangen of onthoofd.

Po třetí anglicko-nizozemské válce bylo Nové Nizozemsko znovu krátce dobyto Nizozemci a přejmenováno na Nové Oranžsko (Anthony Colve se stal prvním guvernérem, do té doby oblast spravovali ředitelé Západoindické společnosti), ale po podpisu Westminsterského míru připadlo město definitivně Anglii a od té doby má trvale jméno New York.

RRITSKÁ ZÁMOŘSKÁ ÚZEMÍ V AMERICE

Britská zámořská území v Americe a založení Spojených států

Úsp��šné anglické osídlení východního pobřeží Severní Ameriky začalo kolonií Virginie v roce 1607 v Jamestownu a s kolonií poutníků v Plymouthu v roce 1620. První volené zákonodárné shromáždění kontinentu, Virginská sněmovna měšťanů, byla založena v roce 1619. Harvard College byla založena v Massachusetts Bay Colony v roce 1636 jako první instituce vysokoškolského vzdělávání. Mayflower Compact a Fundamental Orders of Connecticut vytvořily precedenty pro zastupitelskou samosprávu a konstitucionalismus, které se rozvinuly v amerických koloniích. [59][60] Mnoho anglických osadníků byli nesouhlasící křesťané, kteří přišli hledat náboženskou svobodu. Původní populace Ameriky poklesla po příchodu Evropanů z různých důvodů, především kvůli nemocem jako neštovice a spalničky.

V prvních dnech kolonizace mnoho evropských osadníků trpělo nedostatkem potravin, nemoci a konflikty s domorodými Američany, jako například ve válce krále Filipa. Domorodí Američané také často bojovali se sousedními kmeny a evropskými osadníky. V mnoha případech se domorodci a osadníci stali závislými jeden na druhém. Osadníci obchodovali s potravinami a zvířecími kožešinami; domorodci pro zbraně, nástroje a další evropské zboží. Američtí indiáni naučili mnoho osadníků pěstovat kukuřici, fazole a další potraviny. Evropští misionáři a další cítili, že je důležité "civilizovat" domorodé Američany a naléhali na ně, aby přijali evropské zemědělské postupy a životní styl. Nicméně, s rostoucí evropskou kolonizací Severní Ameriky, domorodí Američané byli vysídleni a často zabiti během konfliktů.

Evropští osadníci také začali obchodovat s africkými otroky do koloniální Ameriky prostřednictvím transatlantického obchodu s otroky. [70] Na přelomu 18. století otroctví nahradilo smluvní nevolnictví jako hlavní zdroj zemědělské práce pro tržní plodiny na americkém jihu. [71] Koloniální společnost byla rozdělena ohledně náboženských a morálních důsledků otroctví a několik kolonií přijalo zákony pro nebo proti této praxi.

Třináct kolonií, které se staly Spojenými státy americkými, bylo spravováno Brity jako zámořská závislá území. [74] Všechny nicméně měly místní vlády s volbami otevřenými pro bílé mužské vlastníky majetku, s výjimkou Židů a katolíků v některých oblastech. S velmi vysokou porodností, nízkou úmrtností a stabilním osídlením koloniální populace rychle rostla a zastínila domorodé americké populace. [80] Křesťanské obrozenecké hnutí v letech 1730 a 1740, známé jako Velké probuzení, podnítilo zájem jak o náboženství, tak o náboženskou svobodu.

Během sedmileté války (1756–1763), známé v USA jako francouzsko-indická válka, britské síly dobyly Kanadu od Francouzů. S vytvořením provincie Quebec by kanadské frankofonní obyvatelstvo zůstalo izolováno od anglicky mluvících koloniálních závislostí Nova Scotia, Newfoundland a třináct kolonií. S výjimkou domorodých Američanů, kteří tam žili, mělo třináct kolonií v roce 2 více než 1,1770 milionu obyvatel, což byla asi třetina oproti Británii. Navzdory pokračujícím novým příchozím byla míra přirozeného přírůstku taková, že do roku 1770 se v zámoří narodila jen malá menšina Američanů. Vzdálenost kolonií od Británie umožnila rozvoj samosprávy, ale jejich bezprecedentní úspěch motivoval britské monarchy, aby se pravidelně snažili znovu potvrdit královskou autoritu.

Historie Spojených států (1776-1789)

Americká revoluce oddělila třináct kolonií od britského impéria a byla první úspěšnou válkou za nezávislost neevropské entity proti evropské mocnosti v moderní historii. V 18. století bylo americké osvícenství a politická filozofie liberalismu mezi vůdci všudypřítomné. Američané začali rozvíjet ideologii "republikánství" a tvrdili, že vláda spočívá na souhlasu ovládaných. Požadovali svá "práva jako Angličané" a "žádné zdanění bez zastoupení". Britové trvali na správě kolonií prostřednictvím parlamentu, který neměl jediného zástupce zodpovědného za žádný americký volební obvod, a konflikt eskaloval do války. V roce 1774 schválil První kontinentální kongres Kontinentální asociaci, která nařídila bojkot britského zboží v celých koloniích. Americká revoluční válka začala následující rok, katalyzovaná událostmi jako Stamp Act a Boston Tea Party, které byly zakořeněny v koloniálním nesouhlasu s britskou vládou.

Druhý kontinentální kongres, shromáždění zastupující Spojené kolonie, jednomyslně přijal Deklaraci nezávislosti 4. července 1776 (každoročně se slaví jako Den nezávislosti). V roce 1781 Články Konfederace a Věčné unie založily decentralizovanou vládu - tehdejší Spojené státy byly vpodstatě volnou konfederací téměř samostatných států, v čele s prezidenty, či guvernéry. Volná konfederace fungovala až do roku 1789, kdy byl zvolen první president USA George Washington, vůdce povstaleckých vojsk v boji za nazávislost a Spojené státy se takto přetvořily ve federativní republiku.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Portrait of Cobi Arntzenius-Witsen in the Studio at Ewijkshoeve". 1896.

By Piet Meiners. Dutch. 1857-1903.

> random-brushstrokes

0 notes

Link

🌟💍👸🕺💃🎥 Key figure Willem Witsen could not and did not want to shine himself Museum Jan Cunen in Oss puts the spotlight on Willem Witsen, a man who preferred to stay away from there during his life. The exhibition is not only about ...... 🎶🏆💔📸🎉

0 notes