#white coral beads igbo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Reclaiming Tradition: How Hair Beads Connect Us to Our History

"The wearing of hair jewelry is a beauty practice that long predates our present-day interpretations. "Just about everything about a person's identity could be learned by looking at their hair," Lori Tharps, co-writer of the book Hair Story told BBC Africa about early African braiding practices.

These styles weren't just about aesthetics and functionality. They were also markers of social standing. In Ancient Egypt people commonly wore alabaster, white glazed pottery or jasper rings in wigs, depending on which materials were available locally, they were symbols of status and authority, with those of high class ranking, let's say a young Cleopatra, using them to signify wealth and status.

Hair adornment played a similar role in early West African civilizations. In many communities braid patterns were used to identify marital status, social standing and even age. In present-day Cameroon and Côte d'Ivoire hair embellishments were used to denote tribal lineage. In Nigeria coral beads are worn as crowns in traditional wedding ceremonies in various tribes. These crowns are referred to as okuru amongst Edo people, and erulu in Igbo culture. In Yoruba culture, an Oba's Crown, made of multicolored glass beads, is worn by leaders of the highest authority.

Hair ornaments have been worn by Fulani women across the Sahel region for centuries, who adorn intricate braid patterns with silver or bronze discs, often passed down from generations.

Early uses of hair jewelry were also seen in East Africa. Habesha women from the northern regions of Ethiopia and Eritrea drape cornrow hairdos with delicate gold chains that usually fall past the forehead when in traditional garb. Members of the Hamar tribe in the Southern Omo Valley are known to wear their hair in cropped micro-dreadlocks dyed with red ochre and use flat discs and cowrie shells to accentuate styles.

Some of the earliest beads to be used as adornment were found in 2004 at the Blombos Cave site near Cape Town. They were made from shells and date back 76,000 years."

0 notes

Photo

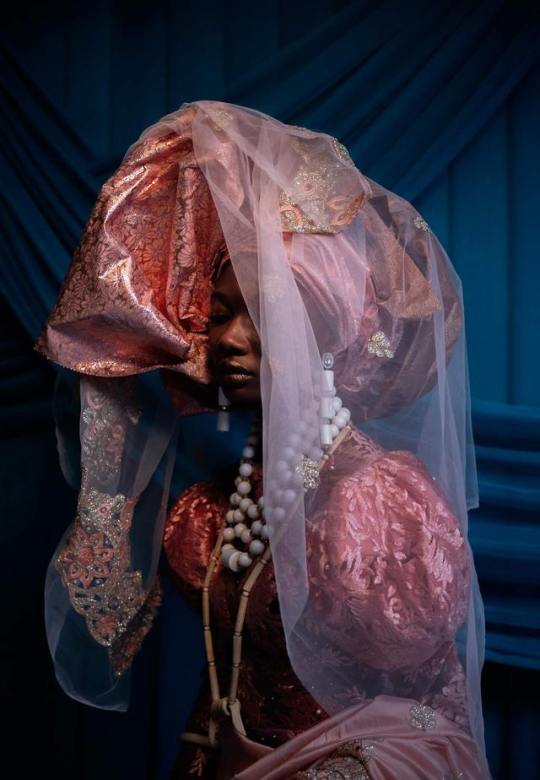

e wá wo mi (*come look at me) – a new photographic series by Nigerian artist Lakin Ogunbanwo. Central to Ogunbanwo’s latest exploration, is the culture surrounding Nigerian brides and marriage ceremonies. He uses veiled portraiture to document the complexity of his culture, and counteract the West’s monolithic narratives of Africa and women.

Ogunbanwo’s interest in expanding the contemporary African visual archive began in 2012 with his acclaimed ongoing project, Are We Good Enough. In this series, he documents hats worn as cultural signifiers by various ethnic groups in Nigeria. In e wá wo mi Ogunbanwo furthers this investigation by representing the traditional ceremonial wear of the Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa-Fulani tribes, amongst others. Rather than objectively archive these as past-traditions, however, he mimics the pageantry of weddings in present Nigeria. He creates elaborate sets of draped fabric as a backdrop for these brides to perform.

The performances these brides carry out are ones of love, familial and cultural pride, feminine strength, and a heterogenous African identity, but they are also the burdens of being wives, mothers and daughters-in-law. The expectation of femininity, and the role of women, are canonised on the wedding day. “From how she dresses, to how she carries herself, to what she is told. She will be fertile, she should be submissive and supportive: These are the things she hears on that day.” Ogunbanwo reflects, “I’ve found weddings to be very performative, and most of the performance generally rests on the bride.” On this day, the bride is admired and observed for her proximity to a constructed womanhood: she is feminine, demure, grateful, emotional, and graceful. Ogunbanwo comments on this by obfuscating the individuality of these women, masking their faces with veils— a style signature to his photography.

The brides are captured in singular portraits, veiled and barricaded off from the fuss of weddings: planners, caterers, decor, family drama, photoshoots, hashtags and groupings of friends and families, identifiable by groups wearing the same fabrics or colours. The attention Ogunbanwo places on these brides, as symbolic individuals, gives these portraits a regality and grandeur. The brides are styled similarly to the goddesses, queens and courtesans in renaissance paintings. They are celebrated women. Ogunbanwo uses the soft lighting and opulence of these scenes as an opportunity to comment on the absence of ‘blackness’ in these archives. He co-opts this visual language to re-imagine Western perceptions of beauty, and to frame these African women as confident, beautiful subjects. The brides are conscious of their role in being looked at, and perform accordingly.

Igbo brides pose with ivory bracelets or in an orange coral beaded cap and necklaces. A Yoruba bride parades in an intricately crafted gele (a pleated, stiff headscarf); a sign of her social status and cultural pride, while holding a feather hand-fan seemingly as a prop to accompany her dancing. The henna-stained hands of a Hausa-Fulani bride fall over a theatrical red lace dress. The brides which fashion his photographs are picturesque motifs of the conflation between tradition and contemporary fashion; global trends and local culture; historical oppression, and present legacy and empowerment. Nigerian fabrics such as Aso-Oke (“prestige cloth”) — culturally specific to the Yoruba tribe — exist alongside lace, damask, silk, velvet, taffeta, adire or guinea.

Ogunbanwo expands beyond the “white wedding” by documenting a Nigerian alternative, and in doing so, believes that there is more than one way to be married, be a woman, and be African.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fabric of Nigerian Weddings

Dola Fatunbi Olutoye, 25, was ecstatic after becoming engaged last November to Dr. Yinka Olutoye, 26. She knew she wanted a traditional Nigerian wedding, but needed help executing the cultural elements of the ceremony, which took place on May 25 in Houston.

Mrs. Olutoye, a pharmacy student from Houston, and Dr. Olutoye, a recent medical school graduate, are both Nigerian-Americans who are part of the Yoruba ethnic group, which is heavily concentrated in the Southwest region of Nigeria.

On the top of her to-do list, after graduating from pharmacy school and starting a residency program, was to shop for traditional fabrics, which have become emblematic of Nigerian weddings today.

“Nigerian weddings are full of color, vibrant, and are flashy,” said Mrs. Olutoye, who has attended many traditional Nigerian weddings in her hometown. “Without your fabrics, you’re not having a traditional Nigerian wedding.”

In Houston and throughout other Nigerian enclaves, like Atlanta, New York and Baltimore, Nigerian wedding ceremonies are especially opulent. Guest lists can number in the hundreds — a cultural holdover from Nigeria, where significant life events were typically community gatherings open to close relatives and loose acquaintances. With such a big audience, a bride aims to impart regality, vibrancy and thoughtfulness in each of her bridal looks.

With the help of her mother, Modupe Fatunbi, who had connections to a fabric distributor in Asia, Mrs. Olatoye picked out the colorful, patterned yards of lace and silk for each of her ensembles. They featured: a champagne and rose gold-color set, heavily beaded with pearls and embroidered flowers for her Yoruba traditional wedding (also known as the engagement ceremony); a royal blue dress with a detachable skirt for her western wedding, which included a conventional white gown; and various fabrics for three thanksgivings after the wedding, when the couple receives well-wishes and blessings from friends and family.

To streamline the process, Mrs. Olutoye enlisted the assistance of Doyin Fashakin, the owner of Doyin Fash Events, a luxury bridal consultancy and events company in Houston. Mrs. Fashakin, also of Nigerian heritage, knew the subtle fashion elements necessary for an authentic cultural wedding, and wears many informal hats during the wedding preparation process — family therapist, budget enforcer and fashion consultant for anxious clients.

“When you’re picking out your outfits, it’s very important that you select something unique and colorful but also of quality,” said Mrs. Fashakin, who along with overseeing the more logistical aspects of planning a wedding, also helps brides source fabrics and accessories for their ensembles from vendors in Nigeria, Switzerland, Dubai and Australia.

What makes a good fabric? “No synthetic fibers or blends; the material should be 100 percent lace or silk,” Mrs. Fashakin said. “The material also shouldn’t bunch or fade. There shouldn’t be loose threads and it should always feel good against your skin.”

Chioma Nwogu-Johnson of Dure Events, a wedding and events company in Houston, said that while planning a wedding in Houston is more cost-effective than in New York, the brides who procure her services still spend from $100,000 to $300,000 or more to host their nuptials. A sizable budget — sometimes $10,000 or more — is usually allocated to wedding fashions. Couples also absorb the cost to outfit large bridal parties and select attendees in aso ebi (translating to “family clothes,” or a uniform dress worn by friends of the couple as a show of solidarity). Some brides opt to send their raw fabrics to trusted tailors in Nigeria, where the craft work is less expensive.

“Nigerian brides spend months searching for their wedding fabrics looking for something distinct — something that no one else will have — and that can sometimes be a tedious and frustrating process for brides,” said Ms. Nwogu-Johnson, whose clients often include affluent professionals, like medical doctors, engineers and oil contractors. “They want to make sure that no other brides are wearing their fabrics. More than anything, they want to make sure they stand out.”

Social media can provide some inspiration for brides. The hashtag #nigerianwedding on Instagram touts more than 3 million posts, showing brides in all manner of colors, fabrics and bridal party size.

The style of dress at Nigerian occasions will vary, depending on the tribe of the celebrants. For instance, brides from the Igbo people, another major ethnic group concentrated primarily in south-central and southeastern Nigeria, adorn themselves with coral beads signifying royalty, and at times use George fabric, a heavily embroidered material from India.

Material made of lace is also popular for many Nigerian brides across tribes, as are other textiles like silk and tulle, embellished with hand-stitched beads, stones and pearls tailored painstakingly to a bride’s taste.

Many brides spare no expense in making what the Yoruba people call their aso oke or top clothes, made of a matching buba blouse and iro, a swath of fabric wrapped around the waist. A heavy sash of complementary fabric, called an iborun, is draped on one shoulder. The bride’s ensemble is matched to her husband’s tunic and pants set, along with his agbada draping and fila hat.

But perhaps the most important part of any Nigerian bride’s look is her gele, a scarf or fabric folded into an ornate shape atop a woman’s head. The gele is standard in African women’s wear, although called by different names throughout the continent. A bride’s look is incomplete without it.

Tying gele requires artistry, nimble fingers and a touch of originality; no two geles are tied the same. “A well-tied gele at a wedding is what an ascot is at the Kentucky Derby,” said Hakeem Oluwasegun Olaleye, a bridal stylist based in Houston who is known within the bridal circuit as Segun Gele. Named for his skill in fashioning the head scarves, Mr. Olaleye is commissioned to wrap geles around the heads of brides and female attendees at weddings around the world.

“Geles are art — it is your crowning glory,” Mr. Olaleye said. “It’s as important as your hair. You can wear a cheap dress and have your head wrap beautifully done and no one will notice your outfit. Your gele is the focal point.”

When Charlye Nichols Egbo, 31, a luxury property manager in Houston, married her husband Stanley Egbo, 38, who works in oil and gas logistics, in March, she employed five distinct dress changes for her traditional engagement and western wedding, sourcing materials from Nigeria and Turkey. With nods to her husband’s Igbo culture — Mrs. Egbo, who is African-American — solicited help from Ms. Nwogu-Johnson and Mr. Egbo’s three sisters to pull each of her distinct bridal looks together. One of her looks was a heavily beaded navy and gold embroidered ensemble with an embellished floral sleeve made from fabric bought in Dubai. Another outfit — a sparkling, two-tone red set number with coral neckwear — was complemented by a fuchsia-laden aso ebi party of 27 and a custom-made white gown by Esé Azénabor, a Nigerian atelier.

“Every suit maker, every dressmaker we used was Nigerian, Mrs. Egbo said. “I could have bought a gown from Vera Wang, but it was important to us to maintain authenticity, which made everything that more intimate and that more special.”

Continue following our fashion and lifestyle coverage on Facebook (Styles and Modern Love), Twitter (Styles, Fashion and Weddings) and Instagram.

Sahred From Source link Fashion and Style

from WordPress http://bit.ly/2KPNTms via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

10 wonderful Nigerian festivals that make us proud of our culture!

10 wonderful Nigerian festivals that make us proud of our culture!

Culture is something that can divide or bind, depending on what you choose to make of it, but something that has always made Nigeria unique – nay, made Nigeria great! – are the festivals that we have. Nigerian festivals dating back hundreds of years, each with rich cultural heritage and folklore behind it.

I will personally always maintain that the advent of external religion is killing a lot of our old ways – and not always for the better – but part of our goal here at Viva Naija is to commit these things: our way of life and the ways of our ancestors to perpetuity, lest we forget. Here are ten of our favourite Nigerian festivals!

1. Eyo Festival

Unique to Lagos and traditionally performed on Lagos Island, the Eyo festival is one of the most well known festivals of the Yoruba people.

The word ‘eyo’ refers to the costumed dancers or masquerades, that perform during the festival. The origin of this event is unknown owing to its clandestine nature, but it was previously believed to be associated with escorting the soul of a dead king to the after life or in the welcoming another king. Today, it is called for whenever tradition and customs demand it, although it is usually held as part of the final burial rites of a highly regarded chief in the king’s court. This is visible in the long-held belief that the white-clad Eyo masquerades represent the spirits of the dead and are referred to in Yoruba as “agogoro eyo” (literally: “tall eyo”).

On the Eyo day, the main highway in the heart of the city (from the end of Carter Bridge to Tinubu Square) is closed to traffic, allowing for a procession from Idumota to the Iga ldungaran Palace. The first known date of an Eyo Festival was the 20th of February 1854, to commemorate the life of Oba Akintoye.

The Eyo masquerades in full regalia and dance at the festival

2. Sango Festival

Another Yoruba display of strength and gods, the Sango Festival is held in honour of Sango, Omoekun (“son of a tiger”), from whom the present day Alaafin of Oyo Oba derives the title. Sango was the second son of Oranyan, the first alaafin (ruler), and the seventh grandchild of Oduduwa in Ile Ife. Upon the death of Oduduwa, the grandchildren dispersed from Ile Ife, forming the different Yoruba kingdoms in the western part of Nigeria.

Sango is considered powerful and mighty, a symbol of power and truth. A warrior so invincible that he amassed a formidable empire in Africa and transported Oyo culture beyond the Oyo Empire.

During the festival, the Sango faithful are decorated in beautifully, all dressed in fiery red while the Ifa priests are clothed in white regalia – the two strongest colours of the Yoruba kingdom. Masquerades, drummers and hundreds of traditional dancers still give this festival the feel of one of the most respected attractions in the country.

3. Okere Juju

One of the most powerful events of the year for the Itsekiri people, Okere Juju (or the Awan’kere Festival) is an annual festival celebrated by the Itsekiri people of Okere which is in Warri South Local Government Area of Delta State. It is a fertility festival, which date back to the 15th Century when the community was confounded by a Benin warlord called Ekpenede (Ekpen), but most Itsekiri people see it as the welcoming of the rainy season as it is of utmost importance that the final day ends in torrential rainfall.

Given that the the festival is a plea for fertility and plenty, scenes from the ensuing days depict rites with mimes of sexual acts, phallic symbols and lewd songs replete with fertility images. Explicitly expressive dance and movements take place between the spectators and performers. The Masquerades: (i) Otsogwu-Umale – this is the father masquerade. He is always attired in resplendent white. (ii) Okpoye – This is the mother masquerade. She is always dressed in sack cloth. (iii) Children – Numerous and wear costumes of varied colours. All the masquerades apart from the Okpye, carry two specially designed whips called “Ukpatsan”, which produces gunshot-like sounds when the masquerades whip the floor with it. The festival takes place during the rainy season to ensure a conducive environment for the deity, Okioro, who lives in the waters. During the festival masquerades and other performers splash about in the rains in a symbolic washing away of evil spells and diseases from peoples’ bodies. The festival lasts for five weeks with one performance each week on succeeding days. The festival combines both the sacred, in its numerous rituals, and the profane in its orgiastic dance and lewd songs. Underlying it all, is the expectation and yearning for a life more abundant.

Okpoye, the bride of Otsogwu-Umale dances to the crowd at Okere Juju

4. Leboku New Yam Festival

The New Yam festival is popular all over Nigeria, particularly in the southern parts of the country. The Igbos have their festivals known as Iri ji ohu, Iwa ji or Ike ji while the Yorubas call theirs “Ijesu”.

If you want to experience a New Yam festival that would involve the celebration of the ancestral spirits and the earth goddess though, you should visit Yakurr in Cross River State where the Leboku New Yam Festival takes place. This annual festival packs so many symbols and activities within three weeks. This includes parading engaged maidens, exchanging visits to families, appeasing the ancestors, and ensuring that no one does any intense farming during this period.

5. Argungu Fishing Festival

The popular Argungu Fishing Festival is one of the most famous and exciting traditional festivals in Nigeria. The four-day annual festival dates back to 1934 and has continued with the alluring dynamics growing each passing year. The festival is an all-men affair; women can be present purely as spectators.

The fishing festival is a competition among the fishermen of the area to determine who catches the biggest fish and proves his skill once and for all. The festival takes place at the Matan Fada River in Argungu, Kebbi State.

The sound of a gunshot signals the commencement of the competition, with the anxious and excited competitors jumping into the river to begin the search for the ‘big’ catch. This lasts for an hour, at the end of which each competitor presents his catch for weighing, to determine which fish is the biggest. It is awesome, if smelly, stuff!

6. The Durbars of Hausaland

The durbars have been a part of Hausaland for over five hundred years and their majesty, pomp and splendour is undeniable. The annual festival celebrated in several cities of Nigeria. It is celebrated at the culmination of Muslim festivals Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. It begins with prayers, followed by a parade of the Emir and his entourage on horses, accompanied by music players, and ending at the Emir’s palace.

Durbar festivals are organised in cities such as Kano, Katsina and Bida with the Katsina durbar possibly being the most colourful. Introduced by Sarki Muhammadu Rumfa of Kano in the late 14th century as a way of demonstrating military power and skills before going to war, the durbar has now become quite a tourist attraction. The festival is also an opportunity for local leaders to pay homage to emir throughout the jahi cheering.

Men dressed in traditional clothes ride horses during the Durbar festival in Kano|REUTERS/Goran Tomasevic

7. Sharo/Shadi Festival of the Fulanis

If you have heard of coming of age festivals where young men show off virility and strength, they were probably based on the Sharo or Shadi festival of the Fulanis! In this rite of passage, young men are escorted by maidens to the event venue and led into a ring formed by spectators, their chests exposed. The frenzied drumming, singing and cheers of the crowd combine to create an atmosphere of excitement!

Each participant is flogged by another and they are expected to endure the pain for as long as the exercise lasts, to demonstrate and prove their manhood. Although not all the young men are able to endure the excruciating pain; which at times leaves permanent scars on their bodies, those who do endure to the end are certified mature and free to choose a girl to marry.

8. Igue Festival

The most important festival in the calendar of the Benin kingdom, the Igue festival takes place annually towards the end of the year as Bini chiefs headed by the Oba celebrate the lives and deaths of the obas that have gone before. This celebration is done to invoke their blessing on the reigning monarch, his family and subjects.

The Igue festival, which is a period of offering thanks to the gods for sparing lives and asking for blessings, is also used for offering sacrifices to some deities in the palace. During this period, chieftaincy title holders display their Eben emblem in the Ugie dance as they appear in their attire, according to the type of dress the Oba bestowed on individual chiefs during the conferment of title, while the Oba sits majestically in the royal chamber (Ogi-Ukpo). The Igue festival is also a period given to the driving away of evil spirits (Ubi), and bringing blessings (Ewere) to every home in the kingdom.

9. Onitsha Ivory Festival

While most festivals in Nigeria revolve around men (with some even explicitly banning women from the scene), the Onitsha ivory festival is a celebration of womanhood, beauty and adornment.

Celebrated by the Igbos, the Onitsha Ivory Festival involves wives of prominent and wealthy men gather ivory and coral beads as they prepare for the celebrations. On the day of the festival, the Onitsha woman who has acquired enough ivory and coral to kit herself out in the ivory costume can claim the title of odu or ‘ivory holder’. To qualify as an ivory holder, a woman is expected to have two large pieces of ivory, one to be worn on each leg. Each piece of ivory usually weighs about 56 pounds or 25 kilos so this is no mean feat. Also, the woman has to wear two other pieces of ivory on her wrists. In addition to these are coral and gold necklaces, with which she adorns her herself.

Mrs Asika at the Ivory Festival

Madam Asika adorned with ivory ringlets on her wrists and ankles for the Onitsa Ivory Festival

The women of Chief Asika’s household

Chief Asika himself!

10. Osun Festival

And now, we return to the west as we mention perhaps one of the most iportant festivals in the Yoruba calendar: the Osun festival. At the end of the rains in July/August, the Osun festival is held at the sacred Osogbo forest for seven days where devotees of the river goddess Osun pay homage to her.

At the shrine of this goddess of fertility and protection, the Osun priests not only celebrate their deity but also conduct rituals for the protection of her followers. Followers believe in the potency of the goddess to hear their requests and provide solutions to their problems, as even barren women are believed to be blessed with children when they attend this festival.

The entrance into the sacred Osun grove at Osogbo

#ARGUNGU FISHING FESTIVAL#Benin Igue festival#Durbar#Eyo festival#Fulani shadi sharo festival#new yam festival#Nigerian festivals#Okere juju#Onitsa ivory festival#Osun festival#sango festival

0 notes