#which i think parallels with Michael's own journey to self awareness

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

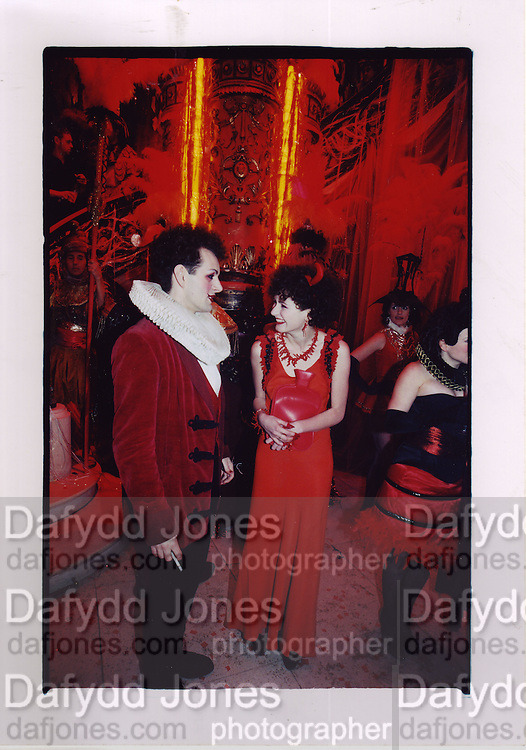

Gorgeous new behind the scenes pictures of Michael in Bright Young Things. His makeup here is everything...

#michael sheen#welsh seduction machine#miles maitland#bright young things#emily mortimer#behind the scenes#god he is gorgeous here#far too much attractiveness in one person#genderfuck!Michael Sheen is the best Michael Sheen#sometimes i think about the fact that Michael has played so many queer roles#and how they all represent different parts of him#Aziraphale is a more mature realized version of Miles#which i think parallels with Michael's own journey to self awareness#i think Michael has been telling us exactly who he is for a long time now#love this so much#let people be who they are#amazing#<3

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things like this are why I miss Michael posting on Twitter the way he once did. How deeply he thinks about things, how he understands Aziraphale in a way no one else does and makes connections between his characters that only he would make. It's not just that Michael interacted with the fandom or wrote numerous "feral" tweets--it's that he shared his passion and his process, encouraging people to think but never telling anyone specifically exactly what to think.

Knowing how he so clearly sees Aziraphale and Miles tied together is especially compelling when you think about how Michael has said that every character he plays is "him," on some level. It makes it so you start to see a path leading from Miles to Aziraphale that goes beyond just what we see on the screen, and might help to explain why Michael thinks and feels as strongly about these characters as he does. There are tweets like this that Michael wrote about GO/Aziraphale all the way back in 2019, and I love that people are seeing these deeper meanings more and more as time goes on...

A little touch of Miles in the night

Do you think about this Michael Sheen post as often as I do?

Cause...you can see what he meant here, right? Comparing Aziraphale (especially this Aziraphale, with this boa) to Miles Maitland. Comparing two Sheens with twenty years between them.

And it's not just a boa. They are so...them. Gayer than a treeful of monkeys on nitrous oxide. Dramatic. Flamboyant. You can see this similarity in their energy in these particular moments.

And yet...is it all? Or there is something else?

Spoilers for "Bright Young Things" under the cut. tw:homophobia, just in case.

You remember what happened to Miles in the end of his storyline? To sweet, frivolous, charming Miles?

The police got Miles' letters to his ex-lover. It was 1930s, and one piece of paper with love confessions inside could lead you to prison. So he had to leave for France to avoid arrest, without even really packing his things. And it's happened just before WW2, so his further fate in soon-to-be occupied France was...unclear, let's say that.

And you know what's happening to our angel here?

He's so silly and happy. He's spending the night with a demon he just recently realized to be madly in love with. Crowley trusts him - as he showed in another round of their peculiar roleplay. He was able to be a terrible magician for one evening. This is a perfect evening, right? He's happy and is ready to share this happiness with the whole world.

There is knock in the door. In this second Aziraphale is beaming and shouts "Enter!".

The next second the door will be opened. Hell is gonna come into the dressing room. Hell that has evidence of an impossible, criminal connection. Hell, ready to trample not only over this second joy, not just this evening - but all past and possible future evenings too. Ready to destroy all of Crowley, and with him, all of Aziraphale.

All thanks to one piece of paper.

……. It was good that Aziraphale knew that trick with the photograph, wasn't it? After all, he and Crowley have nowhere to run to within the confines of Earth - the jurisdiction of Heaven and Hell is somewhat wider than that of an English court.

#good omens#aziraphale#bright young things#miles maitland#michael sheen#welsh seduction machine#cinematic parallels#sometimes i think about the fact that Michael has played so many queer roles#and how they all represent different parts of him#i think about that a lot#Aziraphale is a more mature realized version of Miles#which i think parallels with Michael's own journey to self awareness#i think Michael has been telling us exactly who he is for a long time now#thoughts#discourse#reblog

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

They're not building to buddie happening. Buddie is not happening. Buddie is a crack ship. The creators have repeatedly said nothing about buddie is intended to be romantic. And you wanting Buck to toss aside his canon female love interest for a man when it's never even been confirmed he's interested in men, wanting Taylor to essentially be a placeholder and there solely to emotionally support Buck until he doesn't want her anymore, is misogynist. Get some therapy.

I specifically said I don't want Buck to toss aside Taylor, but I think your comprehension skills are just bad, huh, Nonnie?

In my other post [here], I said I don't want the writers to forget Taylor once her "purpose" is completed. Purpose with quotation marks Nonnie, which I think you missed just as much as you've missed the obvious build-up of Buddie, which is (hoo-boy I can't believe I have to say this) not a crack ship! Buddie is a real, deliberate ship, fighting the queerbait-industry that Hollywood has become in general, and if you can't see that that's on you. Don't believe Buddie is actually going to be real still? Don't believe that the creators/actors are okay with Buddie? Then check these out:

Oliver Stark telling off a person for saying homophobic shit.

Meta by the amazing @matan4il who keeps on giving incredible metas to this fandom: Buck and Eddie's Dating Parallels (and many, many more but you know what Nonnie? I think I've given you enough reading material as it is).

Eddie Diaz' very real Queer Awakening (and Buck's future Awakening/Might already be aware) by @yramesoruniverse

By @kitkatpancakestack: Eddie's Storyline | Buck's Storyline | The Buckley-Diaz Relationship told only in quotes said by Buck and Eddie and Chris signifying the importance of each other in their lives | Buck and Eddie are TOTALLY not meant to be lovers no what do you mean (they totally are tho)

If you don't want to have them become canon, maybe check your homophobia, Karen. Maybe even go to therapy, take your own advice.

As for Taylor being there to "only" emotionally support Buck. Nope, that's not it, Nonnie. Buck has his FireFam + Maddie to emotionally support him. I don't think he needs Taylor for that. His relationship with Taylor isn't even based on needs; it's based on wants. Buck wants someone to come home to, and that for now, is Taylor. Taylor wants Buck, as simple as that, (also because her most shown traits are her being an absent girlfriend and being more into her career, I don't really know much about her wants) and she has him. But is this love? Is this being in love? Nope. Not at all. This is a journey for both of them, and I can only hope that their destination is to being a better version of themselves.

Remember Abby, Nonnie? From S1? Would you say that whole arc was biased against Buck, given that Abby "used" Buck to reach her emotional epiphany? Because she left him, didn't she? She left him to find herself, and so what would you say happened here, Nonnie? Was Buck a placeholder here?

Similarly, let's see another S1 arc: Athena and Michael. Michael also "used" Athena according to you, didn't he? Used Athena as a placeholder? But what is it he really did? He came out as his true self. He finally felt ready to admit it to his family, to his closed ones, that he is something other than what he previously thought he was. That he made others think of him as. We don't know when he admitted it to himself, but we do know that Athena took some time to really digest that—that her husband of over 20 years is gay. And that's valid as fuck. She can take all the time to take that in, because she was in love with someone for two decades and she still didn't have all the pieces of him. But now? Fast forward five years later? Athena and Michael are good friends. They're family still.

What I'm getting at is this, Nonnie: Taylor is not a placeholder. Taylor is not a goddamn prop. I don't want her to be one, not like Ana Flores clearly was (and haven't you asked yourself Nonnie, why that break-up happened? Eddie figuring himself out is why). Taylor is there in Buck's life and it literally has nothing to do with her when Buck figures out he loves Eddie. Buck likes Taylor, they're together, maybe he even loves her, but maybe, just maybe, it's the kind of love that makes them good friends and not lovers. Like Athena and Michael.

This show is literally about finding who you are, and moving on in life. Buck and Eddie not yet knowing they like men (or are in love with each other) is just another journey waiting to happen, Nonnie, and I feel sorry for you because you can't see that Eddie has already started on his.

#answered ask#9 1 1 show#evan buck buckley#eddie diaz#taylor kelly#buddie#it is very VERY real#idk why man you thought that sending me a#hate mail#was a good idea but whatever#have fun learning new things nonnie

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

I thought there were three Large Meta Posts I wanted to make about 14.17, but the more I try to focus on any one of them, to sort out exactly what I want to say on each topic, the more I’m realizing that they’re not three separate topics, and this is giving me fits...

1) Jack, and what everyone has known and/or suspected and/or been concerned about regarding his soullessness and his newly regained powers

2) blame vs guilt vs responsibility for all of TFW

3) the parallels and observations of the two “outsider” characters of the week-- Anael’s observations and assumptions about Cas and her certainty that Jack’s soul is completely gone, and Nick’s assumptions about Dean and how he felt about his possession by Michael (because obviously one is a BLATANTLY wrong assumption, and the other is merely... kinda shady...)

I’m also curious as to how Nick even KNEW how to contact Lucifer in the Empty. Last we saw, his desperate prayer awakened Lucifer, but where did Nick learn what he needed to do regarding the angel grace and Donatello, the ritual he needed to perform to even make that phone call to Lucifer for instructions on how to free him? Did he get that from those demons? I mean, if the demons had that info all along and were as desperate to get Lucifer back as Nick was, why didn’t one of them collect that grace and do what Nick did in the first place? Did it only work for him because of that “open phone line” to their former vessel that we learned about way back in 5.03? Is that something that Nick just had lying around in his memory bank from when he was Lucifer’s vessel? Or was his awareness of this stuff tangentially related to how Crowley tinkered with his vessel in order to make him Lucifer’s permanent vessel back during s12?

And I’ve read some assumptions about what Anael’s connection to this all might be, because how COULD she know for sure that Jack’s soul really was all gone? Which brings me to the first part of point 3 above... Yes, it could be that Nick and/or one of his demon buddies contacted her and made a deal for the little bit of grace they used in that spell, but we also know there’s shady characters like Sergei from 14.07 who deal in that sort of thing. A LOT of angels fell back in the day, and we know when they do their grace sort of... crash lands on Earth (like Anna’s magical grace tree from 4.10). For someone who knows where to look, there’s probably all sorts of shady things stashed around the world, you know? So I’m not ready to say that Anael is in league with Lucifer in this yet. I think she’s smarter than wanting to bring him back, for thinking that he’d be any different than he’d been the last time she’d dealt with him. She is, after all, a good businesswoman.

But that brings me to her assumptions about Jack, and about Castiel, and about God himself. She’s lost faith in Heaven’s mission, in God himself, and has decided that without that connection to God, everyone is all alone. So she does what she can to change things, to help people. Yeah, she does it for money, but she also does it because it helps people. It’s how she connects to the world, her radical choice to do what she can to make life a little better for at least some of humanity. That’s the mission she’d believed in.

And yet, because of that work, she’s spent a LOT of time really looking at humanity, really looking at what people do and the reasons they do them. Not only is she a good businesswoman, she’s also good at reading people, seeing through their BS. I mean, like the other famous faith healer in the series-- Roy LeGrange-- who described how he chooses people to heal: he looks into their heart, which in another manner of speaking, is just a cold read of someone the way Melanie in 7.07 did:

MELANIE: I'm off the clock. Also not psychic. What? It's an honest living. DEAN: Interesting definition of "honest." MELANIE: Well, I honestly read people. It's just less whoo-whoo, more body language. Like you two – long-time partners, but, um... a lot of tension. [Gestures to SAM.] You're pissed. [Gestures to DEAN.] And you're stressed. It's not brain surgery.

Well, Anael might think she’s got Cas figured out, but considering her entire foundation for that assumption is skewed because of her own personal assumptions about God and Cas’s reasons for leaving Heaven, and his drastically different lens for the human experience than Anael has made it impossible for her to clearly see and understand his entire situation makes me doubt her proclamations about Jack.

I mean, to go off down a minor tangent here, this is where Michael’s statements about God having abandoned the universe as a “failure” are good to remember. I mean, we KNOW the circumstances under which Chuck left this universe in Dean’s hands in 11.23, you know? We KNOW why Chuck doesn’t “meddle” in the universe, and leaves it to the inhabitants to sort out. I have already written this essay back when 14.10 aired, but to sum it up as briefly as I can... it’s the difference between the inflexible mindset Michael adopted regarding what HE believed would be his “reward” for completing Chuck’s prophecy and bringing about the Apocalypse. To his eternal disappointment, that reward never came. Because Michael failed to learn the lesson God had actually set for him: watch over the world, watch over humanity, and understand.

Since Cas is literally the ONLY angel Chuck has ever brought back (multiple times even!) and he’s the ONLY angel who’s actually learned something about humanity and free will, not just through observation but gradually adopting it as his own, it tends to follow that Cas is the ONLY angel who actually got this point. Chuck set the challenge, and Michael was too dumb to do anything other than activating his Universe Failure Self-Destruct Button. Faith vs Free Will... he lost that bet.

Dean, and all of TFW, WON. They got the reward. Unfortunately Lucifer was still left dangling out there to stir up new troubles, because HE, like Michael, failed to get the lesson. Instead of understanding that this wide open universe full of potential had been the reward, Michael and Lucifer both expected Chuck to stick around to continue parenting them. And that was never the deal.

Anael is kind of in the same position, except she understands that she has choices in what she does next. She chooses to do good with what power she has (yeah, even if she charges people for her services-- $300 is still a STEAL for a complete cure for what ails you, you know?). But unlike Cas, she does what she does for HERSELF. And as Cas pointed out, her “happiness” sounds very lonely. Anael can’t even disagree, but assumes without without God, everyone is lonely. As if God was the only connection of any import in the universe. As if God’s intent hadn’t been for all of us to love one another as we have loved him. I mean... That’s kinda... the whole point of existence.

And Cas HAS that (or, well, when things aren’t all going to heck in a handbasket, he has that) with his chosen family. Obviously Cas is still on his journey to understand his true place within that family, and we know the entire Winchester Family Bus is about to hit a landmine. But Anael employed a lot of her strategic cold reading skills on Cas.

She DIDN’T, she COULDN’T know for sure that Jack’s soul is completely gone, but what else could power Cas’s desperation to contact God-- aka the only being that can restore a soul-- if he wasn’t at least afraid of that being true. I mean, I don’t think Anael’s statements she presented as facts were actually based on cold, hard fact. Because of how she framed her knowledge of Joshua’s “long distance call” to Chuck after the fall. She just wanted those earrings... When Cas collected the earrings from the table in the Waffelette, she made a strategic play to earn herself those earrings:

[Cas reaches over to collect the earrings and Anael reconsiders] ANAEL: But… there was a rumor. A whisper, after the Fall. Joshua placed a long-distance call, and God picked up. CASTIEL: Okay. How? ANAEL: I don't know. I wasn't there. But I know someone who was, and I can take you to them.

And then after searching Methuselah’s shop, we learn the actual truth-- not just the rumor that Anael had believed before:

CASTIEL (picking up an amulet similar to the one Dean used to wear): No. The one I know, it-- it glows in the presence of-- of God. This is what we're looking for. METHUSELAH: Good eye. Joshua forged it after he Fell. ANAEL: That thing talks to God? METHUSELAH: Only one way to find out. CASTIEL (clutching the amulet): God… I don't know where you are. I don't know if you can hear me. But please. Sam, Dean-- we need you. Please. METHUSELAH: Yeah, it never worked for Joshua, either.

IT NEVER WORKED FOR JOSHUA, EITHER. I mean... Anael had presented it as if it had, you know? So she’s perfectly comfortable working on assumptions-- just like the assumption that God doesn’t care about them or else he’d “meddle.”

To address the other half of point 3 in my original list at the top of this essay, there’s Nick’s assumptions about Dean. I think Nick actually believed that Dean had the same sort of deluded “connection” with Michael that Nick thought he had with Lucifer. That Dean was as power-hungry to play host to an archangel as he had been, and that his life had lost all other meaning without that self-important connection.

NICK: I get you, Dean. You and me, we're almost like brothers, you know. Michael, you, Lucifer, me-- we both know what it's like to be hog-tied to a nuclear warhead, man. DEAN: Mm. [Dean punches Nick again] Cut the crap. Where is he? NICK: You're never the same after something like that, are ya? Being one with one of them. It changes you. Makes you more than human. Come on, Dean, admit it. With Michael, you were a prince. Now you're just a broken Hunter.

Because we know Nick rejected everything about his old life, like a drug addict looking for that high again. He liked the feeling of power that we know Dean hated. Just like Jimmy Novak hated being “chained to a comet,” and yet chose it to save his daughter from that fate. Nick rejected his family for the chance to experience it again. It made him feel special, more important than everyone else, to have been “chosen.” And just... ewwww.

Nick was merely the Worst Version of Jeffrey in 7.15, who became the murderer in hopes of reuniting with “his demon.” And in the end, his demon rejected him, because Jeffrey had only been one of a string of victims that demon had used to create mayhem and twist souls toward Hell. I mean, Jeffrey had been disposable to the demon, just like Lucifer didn’t really care about Nick. Like he didn’t really care about Azazel or Lilith or any of his other loyal demons. He just wanted back in this world.

But Nick couldn’t see that Dean in no way felt the same about Michael. Dean doesn’t lust for power at any cost. He only wanted to be free of that.

Nick also made a similar wrong assumption about Sam, in their fight when he threw this line at Sam as if it was a taunt:

NICK: Lucifer's perfect vessel. Not so perfect now, are ya?

That line didn’t have anything to do with Sam, who has rejected Lucifer over and over again since his original possession and time in the cage. I mean 11.10 had Sam reject him again. To his face. Even if it meant the Darkness would swallow the universe. Sam would NOT play vessel to Lucifer again. So what Nick considered a taunt, to Sam it probably came off more like a compliment. Why yes, thank you, I’ve grown a lot since I believed the only role I could play was as Angel Condom to save the world. And that.. was NEVER a fate Sam had wanted. He’s been TRAUMATIZED because of his experiences, unlike Nick who seems to revel in his.

So assumptions are not working out well for characters in this episode... :P

But that also leads us into the other two items on my original list up there. All season long, everyone’s been concerned about Jack-- first as a function of his gracelessness and how he sickened and died because of that, and now as a function of his soullessness and how his stolen grace has been malfunctioning because of that. We know from the preview for 14.18 that Cas is going to finally come clean about what he saw in 14.15, when Jack killed Felix the snake...

I think Dean’s reaction in the promo isn’t specifically directed at Cas. I mean, yeah, he says the thing to Cas, and he’s ANGRY about it, but I think this is more of a tipping point combined with a convenient target than it is about him truly believing that the entirety of the blame actually falls on Cas. I mean, Dean has been single-handedly blaming himself for everything having to do with Michael all season long.

If only he’d locked himself in the Ma’lak box and tossed himself in the ocean before Michael escaped and Jack was forced to burn up his own soul to destroy Michael! If only Dean had been stronger and kept Michael locked up in his brain! If only he’d known better than to play directly into Michael’s trap in 14.09! If only he’d never said yes to Michael in the first place! If only he’d been stronger when Michael took him over the first time! WOE IS DEAN!

But also, Jack has been similarly blaming himself for everything... if only he hadn’t been so stupid and believed Lucifer back in 13.23, and had his grace stolen. If only he’d killed Michael and Lucifer when he’d had the chance back then, none of this would’ve happened. The AU hunters would still be alive, Michael wouldn’t have used all the monsters to wreak havoc, Dean wouldn’t have had to say yes to Michael to fix his mistake and kill Lucifer...

But Sam has also been blaming himself, for not having been able to find a way to save Dean from Michael, for not being able to save the AU hunters, for not being able to help Jack...

And Cas? Yeah, Cas has been unwilling to “burden” Sam and Dean with some of the terrible choices he’s made on their behalf and on Jack’s behalf, because there were so many other terrible things going on that were more immediate if not more important...

So the fact that they all have been indulging in a lot of SELF blame, it’s kind of interesting that this is the straw that breaks the camel’s back for Dean.

It’s not as if Dean himself hasn’t suspected that there was something seriously wrong with Jack. I mean, why else take him to Donatello’s to talk with someone else who might understand Jack’s current plight? Why else would Dean “test” Jack with the stupid cake choice? I mean, we’d already seen some worrying behavior out of Jack leading up to that, in 14.14 and his insistence that he was fine when *we* knew that he was not fine. But Cas seemed to notice Jack’s deteriorating state, and so did Dean. They just had no idea what to do about it.

Donatello: I'd keep an eye on him, but I think if he seems okay, he probably is. Dean: So he's not like you? Donatello: Oh, no. I'm a Prophet of the Lord, but he -- Jack's probably the most powerful being in the universe. I mean, really, who knows what's going on inside his head?

In 14.15, here’s another little misunderstanding. Dean asks Donatello if Jack was “like you.” I believe Dean meant, “soulless,” but Donatello interpreted it as “power level,” or possibly, “essential nature.” And the entire assumption that Donatello left Dean with, the “if he seems okay, he probably is,” seems like TERRIBLE advice, considering Donatello had just advised Jack to essentially “fake it,” by acting the way the Winchesters would. From that point on, Jack did his best to wear a mask. He was intentionally disguising his issues and instead doing his best to “seem fine.”

We saw it a few times, through interesting camera angles. Most notably at the beginning of 14.17, in the kitchen with Mary, we saw Jack’s dead-eyed stare when Mary was warmly encouraging Jack to open up to her. Her concern for him was evident, but rather than feel comforted by that, Jack flat-out said he found it annoying. But we actually saw him compose his face into a mask of pleasantry before he turned to face her:

And how unsettling was that?

But Mary definitely suspected that something is seriously not right with Jack. Just as Dean suspected it in 14.15. Just as Sam and Dean both suspected it at the end of 14.16. They knew nothing of how Jack had killed the snake, though.

I don’t think Cas would’ve left without telling them if he believed Sam and Dean would’ve just... let Jack run errands in town, or left him on his own for a few days to go on a hunt, or left him alone with just Mary. After all, when Cas left, the Winchesters hadn’t left the bunker in weeks. He didn’t have any reason to assume that was all about to change in the few days he’d be gone to meet with Anael.

But as we all know, in times of crisis, when Dean is terrified or horrified or just angry... as he would be over Jack gone rogue and Mary MIA or even possibly dead (this remains to be seen, but I suspect we’ll find out soon enough...), this will also be a breaking point for Dean, where he just can’t take any more of the blame onto himself, and unfortunately for Cas, he’s the one on deck to take the next hit...

(hooray, baseball metaphor)

So while Jack has been actively deceiving everyone as to his status-- partly because I really don’t think he gets just how messed up he is, and why anyone is worried for his sake, but also because without his soul he’s resorting to the same sort of black-and-white value judgments he did when he was a newborn and therefore can’t really see how messed up he is-- everybody else around him has had their suspicions about him, but they have ALL been afraid to compare notes, so to speak.

Sure, Cas didn’t tell them that one thing he saw that freaked him out enough to go seek out God’s help behind their backs, but similarly, Mary didn’t speak up about Jack’s reactions to her, and Dean didn’t speak up about his unsettling road trip with Jack... heck, he didn’t even go inside to listen to Jack and Donatello’s conversation! He was so unsettled between the snake in the back seat of the Impala, and the fear that Donatello would confirm his worst fears about Jack and the state of his soul that he stood awkwardly next to the car for the duration. Dean blames Cas for not telling him about how unstable Jack was, when just two episodes ago Dean was actively avoiding dealing with just how unstable Jack was... so there’s definitely an element of guilt and self-blame on Dean’s behalf going on with the anger he’s directing at Cas in the promo... not to mention the fact that Dean still doesn’t know about what Cas personally sacrificed to save Jack’s soul in 14.08, and Cas’s denial and desperation for that sacrifice not to have been entirely in vain (and the further guilt, horror, and fear Dean will experience when he does finally learn that truth...)

THESE GUYS AND THEIR FAILURE TO COMMUNICATE WILL GET US EVERY TIME.

The light at the end of this tunnel, though, is that they always do eventually get on the same page again. Unfortunately for us, they’ve just noticed they’re about to head into the long, dark tunnel, and they’ve got a long walk dodging monsters before they get to that light...

I know there was more I wanted to say on all of this, but heck this has gone on long enough and I think I’ve purged enough of it from my brain that I at least unstuck myself from obsessing over it for today. :P

#spn s14 spoilers#spn 14.17#spn 14.16#spn 14.15#spn 14.14#spn 14.18#spn 14.08#spn 13.23#spn 14.09#spn 7.15#spn 11.23#spn 14.10#spn 7.07#spn 1.12#spn 5.03#it's spirals all the way down#the scheherazade of supernatural#using your words#lies and damn lies

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Annabelle Comes Home Review

Annabelle Comes Home is a respectable and dependably spooky addition to the Conjuring franchise. It isn't the scariest—none of the spin-offs have been able to touch The Conjuring 1 or 2 yet—but this is my third-favorite film in this ever-growing horror shared universe and I had a lot of fun watching it!

Full Spoilers…

It was great to have Lorraine (Vera Farmiga) and Ed Warren (Patrick Wilson) back in more than just stock footage, even if they still had reduced roles. I’m glad they touched on the real-life questions surrounding the veracity of the Warrens’ investigations: that’s a good aspect to mine for drama, both for them and for Judy (McKenna Grace) with her peers at school. As far as the Warrens go, it’s hard to play that real-life public scrutiny any further than they do here: there’s no question whether ghosts are real in the movies since we can plainly see that they are. This film finds the Warrens in a more traditional horror setup, with them out of the house and the terrors affecting the teenagers left home alone, but the movie’s creators found the right balance to keep them recognizably “the Warrens” while also exploring that setup. Plus, Farmiga and Wilson are both so good in these roles that it’s nice to see them in whatever new situations the writers can cook up! This setup offered a peek into their home life when they’re not on an investigation and brought a little more variety to this cinematic universe’s offerings. The one thing I would’ve liked from Lorraine and Ed this time was a discussion about whether or not they should continue keeping their haunted vault room in their house with their daughter. They have to decide that they will, given it still exists in the Conjuring films, but I would’ve liked to hear the thought process behind keeping it. Did they have second thoughts at all? Do they just trust that the kids have learned their lesson? Did Judy reassure them that she’d be fine, either through her actions here or with a newfound strength uncovered by the film’s events? Might they even use the archives room to train Judy in the use of her paranormal sensitivity to some degree? (Probably not, given that would mean intentionally exposing her to dangerous demons).

Like the Warrens, the rest of the characters were very likable and engaging. I greatly appreciated that the kids at the center of this film weren't the typical dumb teenagers messing with haunted things for fun or because of carelessness, but were instead aware of and at least a little respectful of the power of the Warren's archives. They were also capable in their own right (at least, as much as they could be in the face of this sort of danger). Judy's struggle with her burgeoning paranormal powers was well-handled and this was one hell of a first experience! The fallout at school from the questions about her parents' honesty was both a smart place to plant the seeds for the movie's main plot and to explore the unexpected (and until now, unexplored in this series) effects on Judy. I wonder if they’ll take liberties and have Judy grow up to follow in her parents’ footsteps someday, because Judy going from scared, lonely kid to opening herself up to the supernatural to save her friends was a great arc that could easily build into a new sub-franchise (particularly as we haven’t seen Lorraine’s early experiences with her supernatural abilities at an extended length). Grace did great with that transition and she was also really good at playing the more everyday character beats like Judy’s conflicting hesitancy and eagerness to open up to a new friend (Katie Sarife) despite pretty much everyone she knew thinking she was a freak (a very relatable tween/teen struggle). That development was a nice, grounded parallel to Judy’s sensitivity to the supernatural. I liked the idea that there would logically be good ghosts out there in addition to the demons the Warrens investigated, just like not all people are bad. That bit of wisdom was a cool moment for Judy’s babysitter and (initially) only friend Mary Ellen (Madison Iseman) to help Judy on her journey, giving Judy the courage to lean into her abilities to help save the day.

Mary Ellen was a refreshing change of pace as a responsible babysitter who truly cared about her charge. I liked her friendship with Judy and their scenes together felt totally natural and lived-in, as if their hangouts had been going on for years. I also enjoyed her displaying no hesitation to trying to put an end to the ghosts once she knew what was going on. Iseman’s acting and Mary Ellen’s writing also made good use of the push and pull between her responsibility to take care of Judy and Daniella’s intrusion into both the Warrens’ house and her romantic life. Mary Ellen’s awkward flirtation/burgeoning romance with Bob (Michael Cimino) was cute and the film included just enough of it to sell their mutual attraction and chemistry, while keeping it at a realistic level for teens who knew each other but didn't really hang out (so there was no "it's totally love already!"). The one beat that rang a little false for me was Mary Ellen and co. going “We’re totally fine!” at the end of all that terror: that was a touch too glib IMO, but as teens trying to save face in front of their peers—especially the guy she liked—it still worked. Besides that, I’m glad the horrors here weren’t just laughed off and there was an honest discussion with the Warrens about this being a serious incident.

Mary-Ellen's friend Daniella gets that talk and it was a nice show of responsibility that she’s the one who pushed Lorraine to call her out on her mistake. Throughout the movie, she was well-drawn not just as a dumb teen looking to stir up some ghosts for laughs, but as someone who had real pathos in wanting to see her dad (Anthony Wemmys) again. While you’re spending the movie thinking that she should absolutely not be exploring the vault and trying to contact her dad, her performance and the writing make it totally understandable that she would. I bought her sadness and guilt and thought she walked the line between accomplishing her agenda and genuinely caring about Mary Ellen and Judy very well. I also liked that she truly seemed interested in Judy as a person, even if she was also using her to see her dad again (if only she’d just asked Judy which artifact could help her!). All three of the central girls have a similar complexity to their characters, pulled between what they want and what’s been forced on them (Judy’s powers and the isolation caused by them and her parents’ reputation), what they’ve been hired to do (Mary Ellen, though she would still be Judy’s friend; her arc has the least tension), and what they’ve convinced themselves they have to do (Daniella seeing her dad again, which makes her a nice foil for Judy in that the paranormal is what she’s seeking but her pull away from it comes from befriending Judy). That’s a cool common building block to these characters that immediately makes them multi-dimensional, a state that’s only further enhanced by the actresses’ performances. Ben was fun as an awkward teen with a crush, and I liked that he wasn’t too toxic, like you might expect from a high school boy in a horror movie. Another refreshing twist (and a bonus gift stemming from the public scrutiny about the Warrens’ cases) was that all the kids readily accepted that ghosts were real rather than having to go through the motions of beginning to believe in them.

While this was entertaining, I’m over Annabelle as an antagonist at this point: she was fine here, but the other ghosts definitely felt like more of a threat and stole the show while it felt like the doll didn’t do much of anything (even though it was the object pulling the other ghosts to the house). I wouldn’t mind if this were the last Annabelle movie, as it seems like they’ve said all there is to say about the doll. They also included a nice full-circle tie back to Annabelle Creation with a brief vision of her human self (Samara Lee), making it feel even more like this is the last one. Thankfully, there was a sizable monster mash of new ghosts here too! While I would’ve liked some more focus on each of them (a longer haunting act would’ve been nice), I liked what we got and there was a solid variety to the types of scares they generated. The Ferryman was scary and I liked the mythology behind him as well as his appearance. The the coins hitting the floor and rolling in to view to herald his approach were really creepy-cool, and the rules about him appearing in the dark vs. disappearing in the light were used against and by him really effectively. At one point I was hoping the “werewolf” case would be the basis of Conjuring 3 since it seemed like an original take on both a possession and a werewolf movie, but I guess not. Still, I liked that they got some classic werewolf imagery out of the Black Shuck (Douglas Tait) when it ripped up the car. The Bride (Natalia Safran) and the typewriter brought a classic ghost sensibility to the mix and the Feeley Meeley game was bizarre even before it was haunted! The movie definitely left me wanting to know more about the other ghost artifacts in the Warrens’ vault, especially the cursed samurai armor and the future-telling TV. Maybe they could make a web series or something exploring the cases that brought the vault objects to the Warrens’ attention!

Annabelle Comes Home has a strong cast with well-written and atypically alert characters facing a good variety of specters. The pacing’s solid: they take their time introducing us to the characters, which helped generate fear for them when they were put in danger and made the film feel like a throwback to 70s horror, which is fitting given the film’s setting. It also helped to defuse any knee-jerk “this is a real dumb plan” reactions to Daniella trying to contact her dad because she explained her mission enough for me to be invested in it (giving her such a strong a need to see him also avoids any “this is what you get for being stupid” reactions when her quest puts everyone in danger because I felt sorry for her). Jump scares don’t bother me—they’re fun too!—and this movie definitely has some effective ones along with the creepy visuals (like the denizens of a graveyard (Sheila McKellan and others) approaching the Warrens’ car that only Lorraine can see). The paranormal attacks seemed more intense overall in the Conjuring films and Annabelle Creation, which are probably the three scariest entries in this franchise so far (though I liked this one and these characters better than Creation’s). The music, both the score and the 70s songs, was well used to creepy effect.

This movie might not have been necessary, strictly-speaking, since we already saw Annabelle get loose in the first Conjuring, but it was definitely a lot of spooky fun! It's a solid haunted house flick with a strong cast and that’s exactly what it needed to be. It’s also a good ending to Annabelle’s spin-off trilogy and got me ready for the next Conjuring with the focus shifting back to the Warrens (and maybe Judy this time?). You should definitely check this out!

Check out more of my reviews, opinions, and original short stories here!

#annabelle comes home#the conjuring#annabelle#mckenna grace#madison iseman#katie sarife#Vera Farmiga#patrick wilson

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love that Michael is aggressively consistent in letting us know exactly where he stands, in and out of character...

screaming at this exchange from when Michael posted about the end of S2 filming

#michael sheen#welsh seduction machine#good omens#aziraphale#sometimes i think about the fact that Michael has played so many queer roles#Aziraphale is a more mature realized version of Miles#which i think parallels with Michael's own journey to self awareness#also these tweets are 13 years apart#and yet the vibes remain immaculate#michael is not hiding#even if he doesn't label it specifically#amazing#reblog

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jupiter’s Legacy: Mark Millar on the Genesis of His Superhero Story

https://ift.tt/3xWTFe6

This article is presented by:

Superheroes have a long history. After flying onto the scene more than eight decades ago, led by Superman, along with fellow octogenarians Batman, Wonder Woman, and Captain America, the pantheon of capes-and-tights characters has expanded to include countless more. And as legendary creators made their mark across decades, the origins and powers of these icons transformed almost as frequently as their costumes.

Meanwhile, the superhero team The Union, from the comic book saga Jupiter’s Legacy, have 90 years of consistent fictional history, with a singular overarching story, envisioned by one man: Mark Millar.

After discovering both Superman and Spider-Man comics the same day, at the age of four in Scotland (where he grew up), the now 51-year-old writer would go on to make a significant impact on the superpowered set. But he wanted his own pantheon.

And with Jupiter’s Legacy, Mark Millar has created a long history of superheroes of his own—now set to be adapted as a Netflix series.

“I wanted to do an epic,” he says. “Like The Lord of the Rings, or Star Wars… the ultimate superhero story.”

Co-created with artist Frank Quitely and published by Image Comics in 2013, Millar calls Jupiter’s Legacy his love letter to superheroes—and part of his own legacy.

The story begins in 1932 with a mysterious island that grants powers to a group of friends who then adopt the costumed monikers The Utopian, Lady Liberty, Brainwave, Skyfox, The Flare, and Blue Bolt. Told on a grand scale with cross-genre influences, the story spans three arcs: the prequel Jupiter’s Circle (with art by Wilfredo Torres), Jupiter’s Legacy, and the upcoming June 16, 2021 release Jupiter’s Legacy: Requiem (featuring art by Tommy Lee Edwards). With the May 7 debut of the Jupiter’s Legacy series on Netflix, the story will now also be told in live action.

Millar established himself in the comics industry in 1993 and crafted successful stories including Superman: Red Son, Wolverine: Old Man Logan, The Ultimates, and Marvel Comics’ Civil War—all of which have inspired adaptations and films, and led to him becoming a creative consultant at Fox Studios on its Marvel projects. His creator-owned titles Kingsman: The Secret Service, Kick-Ass, and Wanted, have likewise spawned hit movies.

But compared to Jupiter’s Legacy, none of those possessed such massive scope and aspiration as the story that explores the evolving ideologies of superpowered individuals, and how involved they should be when it comes to solving the world’s problems. Relationships are forged—and shattered by betrayal—with startling violence and titanic action sequences (both part of Millar’s signature style).

Read more

Sponsored

Jupiter’s Legacy: Ben Daniels Plays Mind Games as Brainwave

By Ed Gross

Sponsored

Jupiter’s Legacy: Andrew Horton on the Importance of Being Paragon

By Ed Gross

“From Superman and the Justice League to Marvel to British comics—inspired by guys like Alan Moore, and so on, I’ve thrown it in there… it’s got a bit of everything,” he says.

That “everything” extends beyond comic books. Millar drew inspiration from King Kong’s Skull Island, and references the cosmic aesthetic of 2001: A Space Odyssey, which informed the “sci-fi stuff.” The writings of horror author H.P. Lovecraft “were a big thing for me,” when it came to The Island, created by aliens, “that existed before humanity, and that these people are drawn out towards where they get their superpowers.” The character Sheldon Sampson/The Utopian is a Clark Kent/Superman type, but his cohort George Hutchence/Skyfox is more than a millionaire playboy stand-in for Bruce Wayne. Rather, Millar based him on British actors from the 1960s—Peter O’Toole, Oliver Reed, Richard Burton, Richard Harris—who were suave rascals.

“I loved the idea of a superhero having a good time, getting on with girls, drinking whisky, smoking lots of cigarettes,” Millar said.

At the risk of sounding “so pretentious,” Millar jokes, he also pulled from Shakespeare. Indeed, the comics are as much a family saga as a superhero one (and written by the much younger brother of six whose parents died before he was 20). Utopian is a father to his own disappointing children, and a father of sorts to all heroes. He is Lear as much as he is Jupiter, the Roman god of gods. The end of his reign approaches, and various factions have their own appetite for power—such as his self-righteous brother who thinks he should be a leader, or Utopian’s son, born into the family business of being a hero, but who could never live up to his father’s expectations, or his daughter who is more interested in fame than heroism.

He views Jupiter’s Legacy as more thoughtful than Kick-Ass, Kingsman, or Wanted. The plot’s driving action hinges on a debate about the superheroes’ philosophies and moral imperatives. It seeks to address a question Millar asked when he was a kid reading comics.

“Why doesn’t Superman solve the world’s problems?” he recalls thinking. “Why didn’t he interfere and stop wars from even existing?… Is it ethically wrong to stand aside and just maintain the status quo, especially when the status quo creates so many problems for a lot of people?”

On one side of the debate, Utopian believes interfering too much with society’s trajectory is a bad move. It’s not that he is cynical; quite the opposite. He thinks things are actually improving in the world. His viewpoint is there are less people hungry across the globe than ever before, and less people with disease. Millar describes Utopian as a “Truth, Justice, and the American Way” kind of hero, to borrow a phrase associated with Superman, and believes capitalism works. As his hero name suggests, Utopian thinks a better world is within reach, even if it takes generations, and encourages even the heroes to be patient and trust people to do the right thing because they are innately good.

“He says, if you look at the difference somebody like Bill Gates has made in Africa—just one guy—if you look at capitalism taken to the Nth degree, then it pulls everybody up, and poverty in places like India, is massively better just compared to a generation ago.”

Besides, as Utopian says to his impatient brother Walter/Brainwave, in Jupiter’s Legacy #1, being a caped hero doesn’t make them economists and, “Just because you can fly doesn’t mean you know how to balance a budget.” Plus, the notion of using psychic powers or brute force to simply make the world “better” is out of the question. Or is it?

The mainstream awareness of superheroes baked in from more than 80 years of stories, and the shorthand that especially comes with 13 years of the Marvel Cinematic Universe commercial juggernaut, has provided Millar with a set of archetypes to lean into. It was true of the hero proxies in the Jupiter’s Legacy books, and he says it’s true of the show. In fact, he says audiences are so sophisticated with regards to these types of characters they’ll be able to immediately slip into his universe, and that “a lot of the hard work has been done for us.” He adds that audience literacy with superhero tropes also provided him something to push against.

“The Marvel characters lock these guys up in prison at the end of these movies,” Millar says. “Everything’s tied up neatly with a bow, the rich are still the rich, the poor are still starving, and the superheroes aren’t really doing anything for the common man in any very global sense. These guys have just had enough of that.”

Millar’s comics technically kick off in 1932, when Sheldon first brings his friends on a journey to The Island, but his story goes back to 1929 when the stock market crashed, and the Great Depression began. This is likewise when the Netflix series will begin, and Millar says it’s because of the historic parallels between then and 2021.

Read more

Sponsored

Jupiter’s Legacy: Who is Chloe Sampson?

By Ed Gross

Sponsored

Jupiter’s Legacy: Ian Quinlan is the Mysterious Hutch

By Ed Gross

“We’ve been in a similar situation as we are now: there’s impending financial collapse coming out of a global pandemic,” he says. “The idea is that history continues and repeats itself, and people make the same mistakes over and over again, and the superheroes are saying, ‘Let’s actually fix everything.’”

Continuing the theme of parallels, when discussing the inception of Jupiter’s Legacy with Millar, The Godfather Part II comes up more than once because of the film’s dual storylines following Vito Corleone and son Michael, separated by decades. However, while the comics contain some flashbacks, the plot doesn’t unfold across different time periods simultaneously. But the Netflix series will shift between eras, with half of the show during the season taking place in 1929, for which Millar credits Steven S. DeKnight, who developed the series.

“The way Steven structured it was really brilliant, because I saw these taking place over two [different] years,” Millar says. “[But] The Godfather Part II track shows you the father and the son at the same age and juxtaposes their two lives.”

As a result, he says the series is a visual mash-up of genres that’s both classical and futuristic.

“It just feels like a beautiful period movie, then when it gets cosmic, and it gets to the superhero stuff, it’s a double wow… it’s like seeing Once Upon a Time in America suddenly directed by Stanley Kubrick doing 2001.”

This is a notable advantage to bringing the story to television, as opposed to making Jupiter’s Legacy three two-hour films as he originally planned with producer Lorenzo di Bonaventura in 2015. Millar says that to tell the Jupiter’s Legacy story properly on screen would require 40 hours, and with a series, what would have been a one-minute flashback in a movie can now be revealed in two hours of its own.

It was another director who has since made a name adapting ambitious comic book properties that extolled to Millar the benefits of television: James Gunn. When Gunn (Guardians of the Galaxy, The Suicide Squad) had a chat with Millar about the project, Gunn said it could never be done as a movie. “The smartest guy in the world is James Gunn,” Millar says.

An exciting challenge of adapting his work for television is that the series will expand on the backstories and concepts of the books. For example when Sheldon Sampson and his friends head to The Island in the first issue, it takes up six pages. Within the series, half of the first season is that journey, and what happens when they arrive.

“Six issues of a graphic novel are roughly about an hour and 10 minutes of a movie; for something like an eight-part drama on TV, you really have to flesh it out,” he says. “It just goes a little deeper than what I had maybe two panels do.”

He emphasizes, however, that these flourishes won’t contradict the comics. Though he sold Millarworld to Netflix, he remains president so he can maintain control of his creations.

Overall the series has made the writer realize the value of television, and while a second season has not yet been confirmed, he’s already thinking about a third and fourth, and how it will dovetail with the upcoming Requiem. The story that began in 1929 continued through 2021, and collected in four volumes, will soon continue far into the future in the concluding two volumes.

“We saw the parents, then we have the present, and then we see their children in the next storyline,” he says. “That storyline goes way off into the future where we discover everything about humanity, superheroes, all these things. It’s a big, grand, high-concept, sci-fi thing beyond that.”

Listening to the jovial Millar discuss the scope of his Jupiter universe, which is imbued with optimism, one might not think this is the same person known for employing graphic violence in his works.

He thinks his films especially are violent yet hopeful, and fun. Kingsman is a rags-to-riches story, and “you feel great at the end of Kick-Ass, even though you’ve seen 200 people knifed in the face.” But he doesn’t consider his writing to fit under the dark-and-gritty label, and he’s not interested in angst, which he finds dull. With Jupiter’s Legacy, the comic and the show, he views the tone as complex but not “overtly dark.”

Additionally, Millar says he thinks society needs hopeful characters such as Captain America, Superman, and yes, The Utopian in 2021—as opposed to an ongoing genre trend of heroes drowning in pathos.

“The Superman-type characters are just now something from a pop culture, societal point of view, we need more than ever,” he says. “The last thing you want is seeing the world as dark, as something that makes you feel bad. Never forget Superman was created just before World War II in the midst of the economic depression by two Jewish kids who were just scraping a living together… I just think it’s so important when things are tough to have a character like that that makes you feel good.”

Even though Utopian suffers for his idealism in the comic, Millar says his ideas are passed on. This is The Utopian’s legacy.

“Ultimately, he wins if you think about it,” ponders Millar.

After a successful career spent creating characters and re-shaping superheroes with 80 years of history, the new pantheon of Jupiter’s Legacy may become one of the defining and lasting features of Mark Millar’s own legacy.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

Jupiter’s Legacy premieres on Netflix on May 7. Read more about the series in our special edition magazine!

The post Jupiter’s Legacy: Mark Millar on the Genesis of His Superhero Story appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3ts8eCS

0 notes

Text

Carlos Ghosn: The C-Suite Fugitive Under Pressure

BEIRUT, Lebanon — Most global fugitives tend to lie low. They do not beckon reporters to televised news conferences or allow themselves to be photographed drinking wine by candlelight days after being smuggled in a box aboard a chartered jet to freedom.But Carlos Ghosn, the deposed auto executive, is no normal fugitive. Unapologetic and unrelenting, he stood at a lectern in Beirut before more than 100 journalists on Wednesday and laid out his case for how criminal charges of financial wrongdoing in Japan are part of a vast conspiracy to take him down. The highly choreographed event, during which Mr. Ghosn took aim at the Japanese justice system and his corporate enemies, was scheduled 415 days after he was first arrested and more than a week after a team of operatives helped spirit him away from house arrest in Tokyo, where he was awaiting trial.“I did not escape justice,” said Mr. Ghosn, 65, wearing an immaculate blue suit, white shirt and red tie. “I fled injustice and political persecution.”For all the bravado he projects, Mr. Ghosn is a potent symbol of globalism under pressure, an imperial executive in retreat.Until his arrest, he ruled an automotive alliance that spanned continents, comprising Nissan, Renault and Mitsubishi. As head of Nissan, Mr. Ghosn was one of only a handful of foreign chief executives of a Japanese company. But the alliance now threatens to fall apart, a parallel for a time when the global trade order and the military and political alliances that once held the modern world together are facing their toughest tests in decades.For nearly three hours on Wednesday, alternating flawlessly through four languages (English, Arabic, French and Portuguese), Mr. Ghosn talked about how “more than 20 books of management have been written about me.” He referred to himself in the third person and talked about the drop in market valuation at the auto companies he once ran. He drew applause from some reporters, and flattered others, promising to take questions from every region.Mr. Ghosn’s presentation felt, at times, like one he would have delivered to fellow executives and global leaders during one of his regular trips to the World Economic Forum in Davos, the annual gathering in Switzerland that has come to be seen as both a forum for world-changing ideas and a convening of the capitalist and self-congratulatory elite.In a sit-down interview with The New York Times after the news conference, Mr. Ghosn sounded more subdued than during his fiery performance in front of the cameras. He expressed regrets about whom he had hired to replace him at Nissan, admitting, “Frankly, I should have retired.” But Mr. Ghosn remained fiercely protective of his legacy, which is badly bruised. “The revival of Nissan, nobody’s going to take it from me,” he insisted. Mr. Ghosn’s story isn’t a neat one. Company insiders have described him as increasingly haughty and imperious. Though he blames the Japanese justice system for its unfairness, he agreed last fall to pay $1 million to settle a civil case in the United States, which barred him from serving as an officer or a director of a publicly traded company for 10 years. Mr. Ghosn did not admit wrongdoing under the terms of the settlement, but it essentially ended his chance of ever running another large global business. A man with passports from several countries and homes across the world, Mr. Ghosn and his wife, Carole, who also faces a Japanese arrest warrant, are essentially stuck in Lebanon, where they have family and own property but are not free from prosecution. On Wednesday, Lebanese prosecutors said Mr. Ghosn must submit to an interrogation over his flight from Japan.France is also investigating whether Mr. Ghosn used company money from Renault to throw a Marie Antoinette-themed party at Versailles in 2016. And Nissan has accused him of siphoning millions of dollars from the auto company to pay for his yacht, buy houses and distribute cash to members of his family — all of which he denies. Mr. Ghosn argued that in most countries, he would not have been held for months in jail for these types of allegations. He said he felt he was being treated “like a terrorist.”During the news conference, he flashed giant slides on a white wall behind him, showing various corporate documents. In explaining some of the questionable personal expenses, Mr. Ghosn used a defense common on Wall Street: He said other executives at Nissan had signed off on the transactions, which made them authorized by the company.Since his arrest in Japan in November 2018, Mr. Ghosn and his supporters have worked aggressively to tell his side of the story and attack his critics.He has employed lawyers on at least three continents, talked to a Hollywood producer about making a movie about his legal ordeal and hired a public relations firm that advised the National Football League on its efforts to reduce head injuries.In France, the “Committee to Support Mr. Carlos Ghosn” formed on Facebook. Some of his supporters there blame the government for failing to stand up for Mr. Ghosn, a French citizen, for fear of angering the country’s “yellow vest” protesters railing against the global elite.In Lebanon, where Mr. Ghosn grew up, he is celebrated as a member of the diaspora of business leaders and artists who have achieved worldwide success. Hours after he landed in Beirut, Mr. Ghosn met with the country’s president, Michel Aoun, and other top leaders, and operatives who helped him carry out his escape had ties to the country. Lebanese supporters paid for billboard ads across Beirut with the executive’s face on them and the message: “We are all Carlos Ghosn.” But in truth, there are few people in the world who have Mr. Ghosn’s money and influence.A grandson of a Lebanese entrepreneur who ran several companies in South America, Mr. Ghosn was born in Brazil in 1954. His family moved back to Lebanon when he was 6, and he later attended college in France.“I’ve always been someone who was different,” he wrote in his autobiography in 2003. Mr. Ghosn went to work in the auto industry after college and made his mark revitalizing Renault. In the 1990s, he helped turn around Nissan by slashing jobs and upending its corporate culture. “It was a dead company,” he said on Wednesday.Mr. Ghosn expanded his auto empire further by creating the alliance of Renault, Nissan and another Japanese company, Mitsubishi.His leadership of Renault, which the French government partly owns, gave him political standing in France. In Lebanon, some people hoped he would run for public office, maybe even president.Mr. Ghosn’s personal and professional empire collapsed when he was arrested at the Tokyo airport on his return from a trip to Lebanon. By that point, he had stepped down as chief executive at Nissan, but was still its chairman.From the airport, Mr. Ghosn was taken to jail, where he was forced to live in solitary confinement for weeks at a time. He was allowed to shower twice a week and was let out of his cell for 30 minutes a day. Prosecutors, he said, hid the evidence against him and prohibited him from contacting his wife in Lebanon.He was released on bail, but he was jailed again in April after he announced that he planned to speak with the press. Last fall, Mr. Ghosn said, his lawyers told him that his case could drag on for five years, which he said was a violation of a basic human right to a speedy trial. It wasn’t all glum. Two days before his Dec. 29 escape, his secretary made him a reservation at a Tokyo restaurant where he enjoyed his favorite salad with sesame dressing, according to the restaurant’s manager. He posed for photos with about 40 customers.Mr. Ghosn wouldn’t talk on Wednesday about how he got from Japan to Beirut, despite reporters’ attempts. Government-authorized media accounts from Turkey, where Mr. Ghosn landed on the first leg of his journey, have said he was smuggled inside of a large box from an airport in Osaka, Japan.The box was loaded into the storage area of a private plane, which was accessible from where the passengers sat, according to the Turkish account. The two operatives working with Mr. Ghosn told the flight attendant not to bother them.After takeoff, Mr. Ghosn was let out of the box and sat in the passenger area, which contained a bed and sofa and was separated from the front of the plane by a locked door. For about 12 hours, the quintessential global citizen was officially stateless, flying high above Asia in secret.The Bombardier jet landed in the rain at Ataturk International Airport in Istanbul. A car pulled up to the plane and then drove to another jet parked a short distance away, according to the Turkish media. That second plane then took off for Beirut.At least 15 operatives were involved in the operation, and some of them were not aware of whom they were extracting from Japan, according to a person briefed on the operation. They assumed that the plan was to rescue a kidnapped child.In the interview on Wednesday, Mr. Ghosn said he had planned the escape himself, but with help from others, whom he wouldn’t disclose. “Little by little,” he said, he began to think through a strategy for getting out. “When I started to do that, it kept me motivated. It kept me alive.”During the escape, he kept telling himself: “You need to always remember what happened to you. No matter what, never forget that.”Ben Dooley reported from Beirut, and Michael Corkery from New York. Reporting was contributed by Vivian Yee from Beirut, Hisako Ueno from Tokyo, Liz Alderman from Paris, and Emily Flitter and David Yaffe-Bellany from New York. Read the full article

#1augustnews#247news#5g570newspaper#660closings#702news#8paradesouth#911fox#abc90seconds#adamuzialkodaily#atoactivitystatement#atobenchmarks#atocodes#atocontact#atoportal#atoportaltaxreturn#attnews#bbnews#bbcnews#bbcpresenters#bigcrossword#bigmoney#bigwxiaomi#bloomberg8001zürich#bmbargainsnews#business#business0balancetransfer#business0062#business0062conestoga#business02#business0450pastpapers

0 notes

Text

I can think of a few reasons...

All I wanna know is why Mr. Sheen avoids straight roles like the plague

#sometimes i think about the fact that Michael has played so many queer roles#and how they all represent different parts of him#i think about that a lot#Aziraphale is a more mature realized version of Miles#which i think parallels with Michael's own journey to self awareness#i think Michael has been telling us exactly who he is for a long time now#even if he doesn't label it specifically#david is lowkey bi and michael is highkey bi#discourse#reblog

633 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Jurassic Park Taught Me About Personal Finance

*Jurassic Park movie and book spoilers below*

There has always been something thrilling and enticing to me about dinosaurs.

They seem like a fantasy, but they were real-life monsters that actually walked this earth. And, though they are terrifying, there's something attractive about them too. They seem to threaten humanity as the dominant species, even from their extinction — reminding us that we're lucky to have made it this far.

The Jurassic Park franchise, especially the first movie, does an incredible job of capturing this idea and sharing it with its global Hollywood audience.

I've always been a dinosaur junkie. Growing up in the early 1990s, I was too young to catch the theatrical release of Spielberg's Jurassic Park movie. I had my fair share of dinosaur pop-up books and action figures though.

Later, I had full-on kids' dinosaur encyclopedias. In high school, I finally watched all of the Jurassic Park movies (the first 3 that were out, at the time) and I read both of the Michael Crichton books. This inspired a years-long period of Michael Crichton fandom and science fiction consumption.

Now, I write a blog about early retirement. I'm realizing that many of the moments that make the original movie so special also apply to personal finance. Maybe my nerd colors are showing, but I feel a similar sense of intrigue and excitement when it comes to financial planning.

Here's why Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park movie applies to personal finance and means more to me than being just CGI and sharp teeth.

There’s a Sense of Excitement and Possibilities

The opening sequences of both the Jurassic Park book and movie build tension and excitement about the possibility of the dinosaurs. Could scientists really achieve this dino re-boot? And if so, should they? The plot has viewers asking themselves these questions, both in the fictional movie realm and in real life.

When our archaeologist heroes finally arrive at Isla Nublar with dozens of the re-born creatures in full view, it's an iconic scene in cinematic history. Groundbreaking CGI (that still holds up decently well, considering its age) and an extraordinary music score from John Williams solidify the sense of wonder and was truly unprecedented for 1993 viewers. The main theme still gives me goosebumps, even today.

via GIPHY

In the movie, the paleontologists, kids, and businesspeople alike (especially John Hammond) experience moments of joy and awe at the sight of the living dinosaurs. I like that both Crichton and Spielberg showed these people across a spectrum of ages and backgrounds — everyone is in awe of the dinosaurs, at least in some way.

The first time the significance of investing and financial independence “clicks” can feel the same way. The compound growth of your investments is an immensely powerful force. It's awe-inspiring. Financial independence can create simultaneous control and flexibility with your time. And, like the appeal of dinosaurs, personal finance affects everyone.

Over the past millennia, the concept of financial independence or retirement didn't exist until relatively recently. The ability to dictate your own schedule and priorities is a thrilling concept that, like the Jurassic Park movie, is really unprecedented in human history.

Be Skeptical — Bad Guys Take Advantage of Good People

In Jurassic Park, bioengineering company InGen seems to be motivated primarily by corporate greed. InGen has developed a groundbreaking technique that lets them harvest dino DNA and fill in the gaps so they can create healthy dino eggs.

Rather than using this technology exclusively for research or gradual entrepreneurship, the company goes all-in and develops a theme park attraction with about a dozen species (including ferocious carnivores). Any viewer or reader could sense that something was bound to go wrong.

In the book, and many of Crichton's other novels, there's an even stronger tone of warning. Crichton's stories repeatedly suggest that corporations are bound to take major risks to achieve possible profits, even at the expense of human lives and society as a whole. This worldview may sound extreme, but it's certainly a valid concern in today’s technological and business climates.

From early on, Jeff Goldblum's Ian Malcolm was skeptical that the Jurassic Park experiment would go according to plan.

via GIPHY

Similarly, you need to maintain a level of skepticism and awareness when it comes to your investments and financial products.

Many people in the financial services industry are not obligated to act in the individual's best interest. Often, investments and insurance products are sold with huge fees and expenses that seriously reduce the benefit of the product. Customers need to be informed and very careful when making investment and insurance decisions.

You Need to Prepare for the Unpredictable

The Ian Malcolm character is a mathematician and he famously specializes in chaos theory, which the movie references multiple times. Chaos theory “seeks to explain the effect of seemingly insignificant factors. Chaos theory is considered by some to explain chaotic or random occurrences.”

Very small, unpredictable factors can cause ripple effects that lead to significant results.

The Malcolm character acts as the voice of author Michael Crichton — the voice of caution and reason in the face of the greedy, hasty InGen corporation. Through the plot, Malcolm is proven correct as the park's plans unravel and the death count grows.

via GIPHY

Many of chaos theory's implications can be applied to personal finance, too. Seemingly small or isolated events can lead to major changes in your own financial situation or in the global economy. So, it's best to be cautious and be prepared. Be aware of the risk and manage it. Some of the best ways to do this are to increase your financial literacy, diversify your investments, or make the retirement transition more gradual and strategic through semi-retirement.

Don't Go at it Alone

As a bit of a corollary to the chaos theory takeaway, the Jurassic Park movie shows the danger in avoiding or disregarding expert input. None of the scientist consultants in the movie were comfortable with InGen's plans for resurrecting dinos. InGen was blinded by their own greed and John Hammond, specifically, was blinded by his own enthusiasm — even though the movie portrays him as good-natured, in a way.

In the book, Hammond is killed by the dinosaurs and it takes more of a righteous punishment tone, due to his lack of caution in designing and managing the park.

The Jurassic Park heroes (Malcolm, the paleontologists, and the kids) make it out of the park alive, thanks to their sober critical thinking and problem-solving abilities — skills that InGen lacked.

via GIPHY

In the same way, it's incredibly valuable to not approach your finances completely on your own. Seek professional input from a fiduciary advisor, if you have questions. Engage with the personal finance blogging community to encourage you on your journey towards financial independence. If you have savvy friends or family members, ask for their advice too when you're not sure how to move forward. You will develop your own sense of what advice is right and wrong. You'll be encouraged, and you'll realize that if a financial product seems too good to be true, it probably is.

It's Not About Dinosaurs (or a Big Bank Account)

The Jurassic Park movie masquerades as a prehistoric thriller, full of monsters and sci-fi-induced adrenaline. But really, as Crichton intended it, it was a cautionary tale. Jurassic Park is about the evils and selfishness of big business, the imperfections of humanity, and a lack of understanding and respect for other life and for the earth's history.

Likewise, personal finance isn't just about running up a high score in your retirement account. Progressing towards financial independence is about higher values that it can unlock — controlling your own future, self-actualization, flexibility, and creating a life that's in line with your own values and goals.

Maybe I'm just a dinosaur and money nerd, but I love seeing the parallels between these two topics. There's something beautiful that the Crichton books, the original film, and the financial independence movements all share — humble reminders of the best and worst of what we can be as humans.

The post What Jurassic Park Taught Me About Personal Finance appeared first on Your Money Geek.

from Your Money Geek https://ift.tt/33iJznD via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

Behind the scenes of filming Bright Young Things.

#michael sheen#welsh seduction machine#please tell me again how people think this man is 100% straight#sometimes i think about the fact that Michael has played so many queer roles#and how they all represent different parts of him#i think about that a lot#Aziraphale is a more mature realized version of Miles#which i think parallels with Michael's own journey to self awareness#bless his bisexual Welsh chaos#miles maitland#bright young things#gifs by me

413 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toxic Masculinity

Have you seen the Gillette ad that inexplicably has conservative America's panties in a twist?

youtube

It's amazing that this ad charges into our already toxic public discourse just as we New Liners are in rehearsal for La Cage aux Folles, containing a song called "Masculinity." Imagine what the right-wingers would think of Albin! Oh, right, we don't have to imagine. That's our story. Yes, M. and Mme. Dindon are alive and well and living in America. After all, we've all seen the many and various indignities imposed on trans Americans by panicky Christians in recent years. It's fascinating to me how much the controversy over this Gillette ad parallels the song "Masculinity" in La Cage. We find the song funny as we watch it, because not only is Albin terrible at performing Maleness; so is Geroges. Albin's the one being "schooled" here, but Albin arguably has more self-awareness than Georges does. This one dialogue exchange over the song's intro is so perfect.

GEORGES. I want you to pick up that toast as if you were John Wayne. (ALBIN prepares, does his best gunslinger swagger, then sits back down and lifts the toast, fanning himself with it.) GEORGES: I thought I said John Wayne. ALBIN. It is John Wayne. John Wayne as a little girl!

It's a punchline but it tells the truth. Albin is a man in his way; he's John Wayne (tough, strong) as a little girl (who loves to play dress-up and house). Makes me think of The Bad Seed. Tellingly in this world, it's Madame Renaud who does the best "masculine" walk for Albin to imitate. And when Georges points that out to him, Albin replies, "It's easy for her. She's wearing flats." His world isn't made for this kind of performance. He doesn't even have the right shoes for it! It's only in retrospect that we realize that Act II cafe scene and the song "Masculinity" are as cruel as Jean-Michel's abuses and betrayals. Jean-Michael wants Albin gone; but Georges wants him to deny who he is -- including his real role as Jean-Michel's mother. Albin is to become "Uncle Al," not even a member of the immediate family! Which is worse? Georges sees Jean-Michel's betrayal, but not his own. Look at the examples of manliness they offer up for poor Albin in "Masculinity." They start with movie stars John Wayne and Jean-Paul Belmondo, both of whom performed their masculinity as much as Albin performs Zaza. And really, they're not telling Albin to think of the actors, but the parts they play on the screen -- fictional masculinity. Georges invokes the French Foreign Legion. According to Wikipedia, "Beyond its reputation as an elite unit often engaged in serious fighting, the recruitment practices of the French Foreign Legion have also led to a somewhat romanticized view of it being a place for disgraced or 'wronged' men looking to leave behind their old lives and start new ones. This view of the legion is common in literature, and has been used for dramatic effect in many films, not the least of which are the several versions of Beau Geste." To leave behind their old lives and start new ones. That's a pretty potent reference. He invokes "Charlemagne's Men," i.e. the Christian Crusaders. That's also really chilling, considering who Georges and Albin are. And a "stevedore" is a dock worker, a manual laborer. (Makes us wonder if Georges has spent time down at the docks...) Then the Renauds up the ante a bit, referencing Charles De Gaulle (France's World War II resistance hero), Rasputin (the notorious holy man to Russian Tsar Nicholas II), and the Biblical Daniel. No pressure, though.