#well you live and you learn i hope master's thesis will be epic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i should upload my thesis today 🥺🫡

#its finished and corrected and all#im just really really scared to do that#bc im afraid theres something wrong with it that i still could correct#and once its uploaded is out of my hands#ahhhhhhhhhh i feel nauseous#honestly im not really proud of it#its not that its bad but that its average#i couldnt do many measurements bc the equipment was broken lol#and there was no time#and the experiments kinda didn't come out how we expected lol#so its a very boring thesis and also i dont like the topic#feels like i wasted so much time for something so irrelevant and honestly stupid#well you live and you learn i hope master's thesis will be epic

1 note

·

View note

Text

Michelle Whittaker

Hello there again, #FeatureFriday fans! Today, we’re offering a special treat: an interview with SUNY Fredonia alum Michelle Whittaker, whose debut poetry collection Surge is just one topic of discussion alongside her experience as a musician, how Jamaican patois informed her writing, and why so many poets are sprinters.

1. You recently put out Surge, your first published collection of poetry. What are some steps of the publishing process that you think might surprise students who haven’t had to deal with that yet?

Well, a little part of the book came out of my thesis. Although some of my professors thought that “this is ready to be sent out,” I didn’t agree. So, I think one surprising part was that I actually stepped away from it for a few years and really took time to think about the arc, so the arc changed a number of times. I went to a few conferences and workshops just to look at particular poems. So, I really took my time. Even when my current publisher came to me and asked if they could, you know, look at my manuscript, they were hoping that it would even be a little longer than it was. And so I did try to address that, but I really recommend taking your time to build the collection that you want.

Other than that, I had a really good and positive process with my editor, we had pretty good communication. It’s more the business part of it, sort of the marketing, I guess. Not on their end, but just: how do you set up readings and stuff like that. They’ll do some, but there’s just a lot of learning curves once the book comes out. Like, how to get it to an audience, to readers, and that was kind of a new process. So, I recommend maybe having a good plan, time-wise.

2. What do you think drew you to poetry as a medium?

Well, I have sort of an off-the-record joke about that. My dad was a marathon runner, and so he was encouraging me to run cross-country, and it was kind of terrible. I used to fall every few seconds. But it turns out that I could sprint! So I quit [cross-country] and was pretty fast. And so, when I’m in kind of funny circles with other writers and running comes up — like, talking about sports and childhood — I’ve found that a lot of fiction writers like cross-country and a lot of poets like sprinting. More short-form. Don’t hold me to this! [Laughs] Obviously you can have epic poems, and book-length poems, but I like something about the short form. I haven’t quite figured that part out.

I started out of music — playing a lot of classical music pieces — and even if a piece of music was twenty pages, it didn’t feel like it. When you’re in the process of interpreting, I guess. There’s a different type of access [to music and poetry]. I feel like, with a novel, I wouldn’t want to be interrupted too often? I’d rather sit and read it like I’m watching a film. Poetry is like snapshots, almost like visual rhetoric in a way. I like that I get to live in this world, and then move to another world; I like something about that.

3. Speaking of music, you were (and presumably, still are) a classical pianist. How do you think your background in music affects your poetry, and do you see any significant connections between your poetry and your music?

I’ll say: I’m in the process of thinking about that right now, but there’s music as an interpreter. As a pianist, I’d likely be interpreting others’ text. And then there’s being a composer, where you’re generating and you’re in dialogue with those who’ve come before you. Sure, you can generate your own without having to learn about Chopin, but in my journey, I felt that I always had a lot of teachers introducing me to new material. And so, maybe the short answer is that poetry is also constantly in that dialogue. Words are constantly being redefined, in the same way, that no ten people playing a Chopin nocturne are going to play it the same. I feel like they have that, at least, in common. But I’m in the process of trying to figure [it] out.

I found writing music much harder. Just gonna be real about it. [Laughs] I had great teachers, and I definitely was emotionally attached to a lot of different classical music. Many types of composers, what they wrote, I was very emotionally invested. And I was actually, even attracted to composers who stood for something? For, what you’d say in today’s terms as “social justice,” statements about what was going on in their particular time that relates to the human condition. I think I set out to do that, but I just never felt like I was creating a piece that said what I wanted it to. So, it might have been that I just turned to words. Because it was a sort of easier access, in some ways. I definitely think that being a musician for all those years helped that skillset, though. And I had great teachers, here at Fredonia, they were very, very supportive.

4. How do you think your education, both your undergraduate at SUNY Fredonia and your graduate work at Stony Brook, have impacted the approach that you take with your poetry?

I think at Fredonia there was just an openness. I was being introduced to a diversity of writers. And that was exciting. I was a big fan of Octavio Paz, and I don’t even remember whose class it was, but I did a whole presentation on him. Or the Surrealists, or…. at Fredonia, I had to take “Western Civilization and the Arts?” There was a set of courses, and I don’t remember the name of it now, but we pretty much had to understand the history of artists and how they collaborated, and their different aesthetics. And though it would have been great to just take sort of an overview, I really appreciated that they had us take those courses. As a musician, or as a budding artist. [Laughs] Just to understand how artists work together. And I did a lot of that [learning] at Fredonia. I got to play, you know? And then contextualize it later, in real life. You’d never know, but all those skills I’m doing now!

Stony Brook was great because one of my professors at Fredonia had introduced the class to, say, Derek Walcott’s work, and by the time I was at Stony Brook I was sitting in a classroom with Derek Walcott. And that was such a wonderful education. But what I liked about Stony Brook was that they weren’t interested in changing my voice, they were just interested in giving me more tools to work with. Prosody, you know, a lot of essay writing. And they encourage you to take writing in different genres, even though I wanted to study poetry. So I really appreciated that, because I do think that different art forms inform each other.

5. Is there somebody who stands out to you as being singularly important to your career as a poet?

One of my teachers, George Dorsty. He was a teacher out on Long Island, just a wonderful storyteller. He loved poetry (I think he’s a haiku master!). He teaches in Virginia, I think, now. We’ve kept in touch. But I’ve had a lot of great English teachers. In my Master’s program, there was Julie Chen and Star Black. Julie’s a good questioner. She’s really great about being attentive to the facts on the page because my mind can really wander. And Star Black, she studied under Ashbery, I think. Good at thinking about different ways to generate. Terrance Hayes, I worked within a few places, and he’s good at sort of asking questions in his poems and just talking about philosophy and poetics. And just not worrying about the mainstream, he was really good to talk to about that. It was nice to hear from a teacher, face-to-face, that it’s okay to be sort of obsessed with the craft and sitting down to get to work. There’s certainly other poets, of course, but those are the first that come to mind.

6. How do you think your experiences as somebody of West-Indian descent have influenced your poetry, mechanically or thematically?

It’s a good question. [Pause] My parents grew up in Jamaica, and I grew up here. But there was a lot of cultural influence in my house. The joke is, when my mom was living in Jamaica and pregnant with me, she said that at the time that there were two basic radio stations. One that played reggae music, and one that played classical music. And she loved classical music! So we just have a joke that that’s where the love came from, somehow, me in her womb enjoying what she was enjoying. And she introduced me to some poets, early on. Well, folklorists. So I’m sure their language influenced my speech, definitely, language patterns, syntax. I sometimes had a little trouble at school as a kid, a little bit of stuttering issues, and I didn’t know if it was because I’d hear something one way at home and hear it differently at school. These might be pretty current, current and reoccurring themes for first-generation kids. I feel like I see it in certain students when I teach. I’m sure that it’s influenced me in that way.

But from some of the poets that I’ve come across who are known here in this country and have West-Indian background, what I feel like I’ve learned is that you can be open. Talk about anything. I feel like those particular poets, like Claude McKay or even Derek Walcott or Louise Simpson — I grew up on Louise Bennett too, she’s Jamaican, one of the folklorists I was thinking of — reading their work, they gave a sense of talking about whatever was on their minds at times when I think that they might not have felt that way? That unspoken permission, that you have things to say.

But in terms of mechanics, I don’t know. My parents had some patois in the house in Queens. Again, the Queens English, which I think had [an effect] on my earlier comment about syntax and recognizing speech patterns. Understanding the patois, and the Queens English, and the standard Long Island American English. I’m sure they all played a part. And then when you get into music, I love Tori Amos, these early-90’s women and indie artists, which also probably played a role.

7. What would say is the most important lesson that poetry can teach us?

Most important? [Poetry] teaches us how to be a better observer of the world. And how to ask a question. I think inquiry as dialogue turns out to be pretty important in the journey. And maybe enjoying the process of creating, in terms of writing words or writing music. I know a couple of writers who have sort of dropped off. Not that they were [necessarily] more product-focused, but that’s what I suspect, and they just didn’t quite find yet what they enjoy about the process. And I do think it probably takes a long time for some people because there is something that they’re tapping into that they want to keep doing. I think that finding your own process and being patient with yourself [is what a writer needs]. But I think it starts with observing. Like, really observing. Not being afraid to look, and question.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

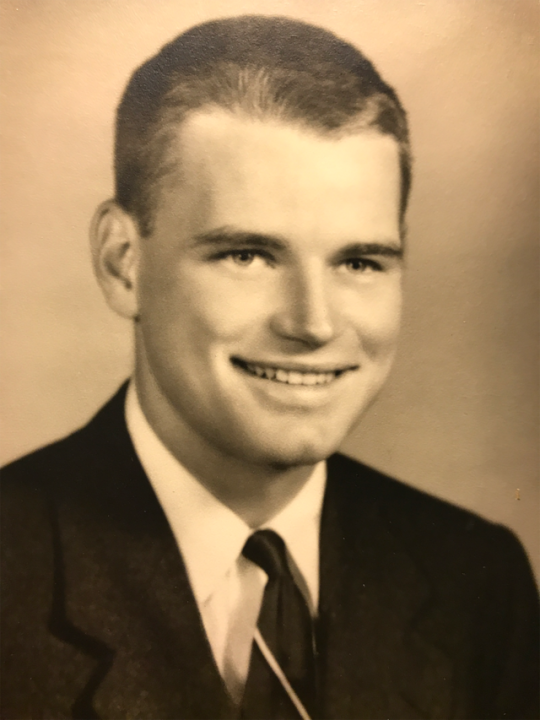

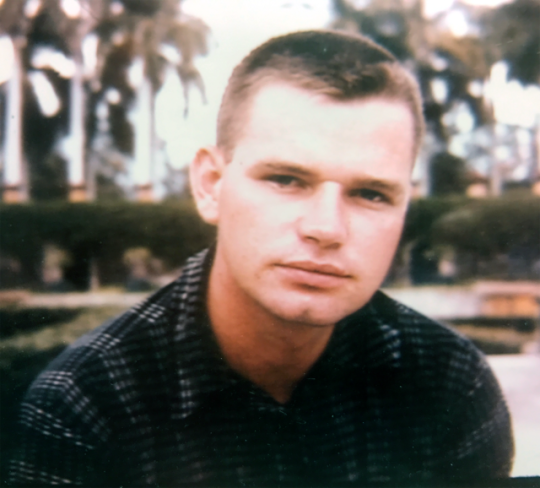

Joseph Wayne Reed, Jr. - 1932-2019

With greatest sorrow and longing, I write to tell you that Joe Reed, our father, is gone.

He was brilliant, funny, unfalteringly sweet, and he recognized us all and loved us to the very last. And that’s the best we could have hoped for when Alzheimer’s disease finally finished taking him from us just before dawn on Monday.

Dad was too huge a figure in my life to be summed up in an obit or a eulogy, but failing to try would deny him the honor he is due.

Born in Depression-era Florida of working-class Hoosiers (his mother was a newspaper bookkeeper and his father an Army medic and eventually a Linotype operator), Dad grew almost fractally; He built a rich life in myriad wild directions towards a sort of glorious crescendo in which everyone around him thrived on his energies and his friendship and his art.

Passionate about the mangroves and palms and snakes and sunset thunderstorms where he grew up on Florida’s Gulf Coast, he Boy-Scouted his way up to Eagle Scout, the highest rank.

Keen for information and knowledge of all sorts, he devoured books. He excelled in school, rode a scholarship to a Yale B.A. - the first of his family in 4-year college - and eventually took a Master’s and a Ph.D. in English Literature that propelled him into lifelong professorship at Wesleyan University.

Mad for movies, he went on to cofound Wesleyan’s renowned Film Studies program, helping launch the careers of more than a few Hollywood blockbuster auteurs. We, his family and friends, gorged on the wonderfully bottomless weekend diet of movies he fed us through a 16mm projector in the darkened living room.

He was forever smitten with his post-high-school sweetheart, Kit. They conspired on witty Christmastime publications, recited epic poetry for fun, proofread each other's manuscripts together aloud - using funny voices for italics and all-caps. They raised three children and taught us by their own example of 61 years of steady marriage how to marry well, endure hardships and disagreements with grit and humility, and stay firmly in love.

The two of them - so inseparable until Kit died in 2017 that they were often known as KittenJoe - saw to it through trips to England and India and Utah and Shelter Island and the 1964 World’s Fair and even the local apple orchard that we kids learned one core lesson: pursue whatever you want in life, so long as you’re happy.

Back in college, I wrote on the dedication page of my multimedia thesis, “For my mother, who taught me how to listen, and for my father, who taught me how to see.”

Because Dad would point things out. And by doing so, he would teach.

He marched us through the Met and the Whitney and MOMA in New York, the Smithsonian in DC, the Museum of Science and Technology in London. A Rembrandt, a fur-lined teacup, a steam locomotive, the Star Spangled Banner itself - pricked enthusiasm to burst from him: “Look, Mackie, isn’t that GREAT?”

We sat together in the St. Petersburg sand, watching thunderheads bluster and flash. “Oh,” he exclaimed, awash in wonder. “Look at THAT.”

“Don’t put your thumb there,” he warned bluntly as the band-saw screamed, teaching me at 12 to respect and love making things with power tools, “Or you’ll lose it.”

And Dad made art. The word is inadequate to his massive body of work.

Decades of beauty and fancy and genuine American weirdness sprang from the moment when, at 32 or so, he casually took up painting pictures of insects and plants because, as he said later, “I was bored.”

His childhood love for insects and the classics blended in wild historical tableaux. He populated that early series of paintings entirely with ants (because, as he said, he wasn’t good at people and all the people in epic masterpieces looked like ants anyway). His Wreck of the Hindenburg is still one of my favorites.

He relished painting the alphabet - a 28-tile template with one letter for each tile (with “&” and “¶” rounding out 26 to a neat 4x7) - for whatever visual topic obsessed him or his patron.

Stretched out on a paint-spattered patent-leather-upholstered chaise-lounge in front of the TV every night without fail, he painted and etched hundreds of alphabets - first of insects and plants, later of movie stars and boxers and Texans and Gertrude Stein and Edgar Allan Poe and the American and British flags and Dubious American Inventions and his wife and his kids.

He indulged in fathomless bizarretés in between:

A series of “Infestations” of Renaissance royalty, beset by bees and worms and beetles.

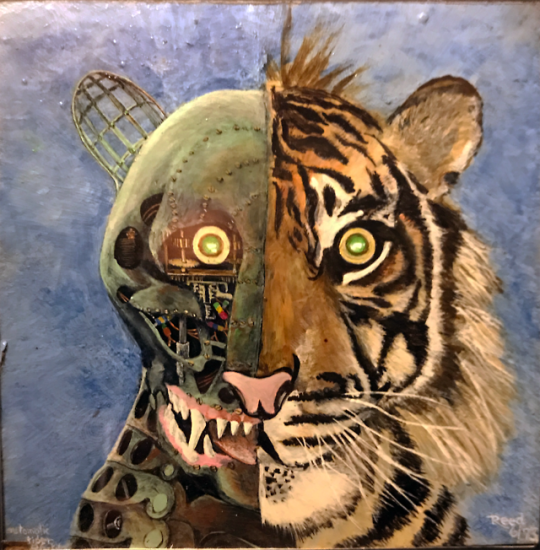

The “automatic” portrait series (inspired by his illustration for Kit’s wonderful short story “Automatic Tiger”) - John Ford and Marlene Dietrich and John Wayne, half their human faces stripped away to reveal clockwork mechanisms inside their metal skulls.

Gen’l. George Custer and Whistler’s Mother plopped down into quotidian scenes as stern and stoic intruders.

Presidents swam Underwater. First Ladies floated in Space.

On and on and on, Dad sketched and printed and painted and drew, and taught, and wrote, and traveled, full of love for his friends and family, scorn for his foes (Republican convention speeches on TV were often greeted with the cry, "Oh, HORSESHIT!"), and nearly seismic energy for the arts.

All of this is inadequate to honor his life, except to add that Dad burned brightly, laughed heartily and was loved (and sometimes feared by his students) deeply.

He never lectured so much as he orated, raged, declaimed. He was as manically amused by Richard Nixon and Donnie and Marie Osmond as he was wowed by Orson Welles and Akira Kurosawa and George Peckinpah.

In a Wesleyan student review of professors, someone noted with backhanded fondness: “NOT AS POMPOUS AS HE’S CRACKED UP TO BE.” He loved the quote so much he put it on his door to help dispel anxiety in office-hours visitors.

Or maybe just to revel in his brand.

As with Mom, there are to be no services for Dad.

Joseph Wayne Reed, Jr. would want you simply to remember him as when you last saw them together; welcoming you into the seemingly endless open house they made of our huge pile of a Connecticut Victorian home, and warming you with their constant cooking and mentorship and generosity and wicked laughter.

You are invited to contribute via this link to Alzheimer’s Los Angeles, an organization that puts nearly every dollar donated towards support of and care for people with Alzheimer’s disease.

0 notes