#we need to colonize the uninhabitable parts of EARTH

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Oren Lore (...LOren...)

So, the thing about talking about Oren's lore is, I don't think it's really possible to have any Thanagarian Lore without basically starting from scratch. So before we get to Oren, let's talk about Thanagar.

Planets are old, but as far as civilizations go, Thanagar was "Worshipping Lovecraftian old gods" old. Worshipping the Elder God Icthultu (Original Dwayne McDuffie Character Do Not Steal!), Thanagarian civilization was able to claw its way up to a respectable level on par with, something close to Mesopotamia. But then they discovered they had Nth metal, and dropped their old gods, getting cool new gods with bird heads, named "The Seven Brothers and Seven Sisters." Arguably they kind of made these gods in their own image, but since Nth Metal is part of the firmament of the universe... they kind of... accidentally made actual gods.

So, yeah. Thanagarian gods are real, and they're actually a problem for earth a lot more often than you'd think because Thanagar kind of colonized us way way way back in the Middle Kingdom of Egypt--but don't get me wrong! This isn't an ancient aliens thing where we wouldn't have figured out how to build pyriamids without Thanagar, it's really more like... our planet was a storage unit for screwy holy biproducts of Thanagar's Nth Metal-created gods. In fact, Thanagar wouldn't have shawarma without us, and Thanagarians love shawarma, so you're welcome, Thanagar.

Anyway, thanks to Nth Metal, Thanagar established a massive interplanetary empire, but, shocker! It turns out empires are generally unsustainable, so they had to keep conquering and colonizing and generally being jerks. So let's fast forward to the point where Thanagar finally decides they actually have to invade earth. We were just kind of... 'there' for them for a really long time, but then they're like, "Okay I know we were storing Thanagarian Satan here who we also accidentally invented, but it would be really efficient if we basically turned this planet into a giant corpse-battery to power a massive Nth Metal Mass Effect Relay to slingshot our warships into Gordanian space. But there's also way too many resources on this planet to outright scorch its surface dead, so we need to conquer the local populace."

Long story short: We kick their butts with the power of friendship (and incredible violence) but our ability to repel the Thanagarian invasion basically kicks off a chain reaction in the empire where colonized planet after colonized planet rebels, and in barely a decade of Earth time, the Thanagarian empire is left a fraction of its former self.

The thing about any empire in decline is, they get weird.

You get a lot of grifters and a lot of straight up assholes trying to "make it great again," chasing an image of the past that never really existed. One such asshole was Sh'ri Valkyr, a death cultist who co-opted Rannian technology and, following a bunch of convoluted comic book what-have-you, basically nudged Thanagar too close to its sun, Polaris. Thanagar's atmosphere ignited, and it has since then been uninhabitable.

Which brings me to my boy, Oren. He wasn't on the planet at the time. He was in the "Hol's Feather" program, one of many desperate and highly morally dubious attempts of the Thanagarian empire to reclaim its former glory. Genetically modified to have biological wings, at 5 years old, Oren was basically in a shitty boarding school that was also lowkey a lab when Thanagar's atmosphere ignited.

(I know. I'm going along with the "Thanagarians don't naturally have wings" canon and then giving my OC biological wings, anyway. I know how convoluted this is.)

But at the time, he was on a planet named Naarith, one of Thanagar's older and more remote colonies that basically saw it generally had more to lose than to gain by attempting secession from the Thanagarian empire, and, through its harsh terrain and general lack of resources, was largely used as a training ground for the Thanagarian legions. Naarith was very cold and very dry, pretty much all of its water locked up in permafrost, glaciers, and ice caps. Think steppes, tundras, high deserts, with the planet's 'tropical zone' being largely mediterranean in climate at best. Really what made it valuable as a training planet for Thanagarian forces was its screaming deadly winds, which either immediately killed you when you took to the air, or made you have to learn how to fly, and fly really well, really quickly.

The climate, the teachers and instructing officers, and Oren's peers were all very unforgiving. The food, frankly, was awful. The entire experience was a crucible of an increasingly destabilizing empire that had just had its heart ripped out. Plenty of the kids in the Hol's Feather program were Downsiders, kids whose parents were poor and desperate enough to subject themselves to a still-refining genetic experiment if it meant possibly getting a better life for themselves and their children. This made the children desperate as well--everything to prove, nothing to lose. In the midst of this, Oren cultivated a reputation of quiet competence. Don't get a big enough mouth to draw attention to yourself, be able to kick the shit out of someone if they try to make a name for themselves by punching down on you. The other thing he had going for himself was unusual quality of observance. He watched everything. He took notes on everything. Wind currents, how the position of Naarith's distant twin suns affect the thermals, what pisses off that instructor faster than anything, where to stand in the food line so that you don't end up with just the water on top of the stew or nothing if you're too far back in line, the shifting alliances of his peers, how the different builds of his classmates affect the speed and strength of their martial styles. He recorded everything in notebooks and squirreled them away for years. When the youths of the Hol's feather program were nearing the completion of their training, finally, one of Oren's instructors found one of Oren's notebook caches.

While plenty of the instructors got pissed off at the impertinence of Oren's notes on them, the more seasoned among them saw the potential. When the graduates (survivors...) of the Hol's Feather program were sorted into their respective positions in Thanagar's legions based on their talents, Oren Koth was placed in the Survey Legion, scouts and spies, now more important than ever now that millions of Thanagarians were displaced in the universe and looking for new homes to settle.

He spent a few years in this survey legion, seeing the universe, becoming more and more starkly aware how Thanagar had made the universe hostile to it through its own actions, how Thanagar's past may have doomed its future, but still he and the rest of the Survey legion searched. Perhaps, he hoped, there could be a future. Perhaps there could be redemption.

Then the Metal Wars happened, and you would think Oren and his survey legion squad would be in too remote an area of space to be affected by it, but no. An entity calling itself "The Hawkbat," clawed its way out of the dark multiverse.

This was a version of Batman from a universe where the Thanagarian invasion of earth succeeded, where the Justice League, and indeed, much of humanity were wiped out in the fight for the planet. Batman, broken by betrayal, and bereft of his family once more, swore to turn the Thanagarians' victory turn to ash in their mouths. And he succeeded in that, sabotaging the Nth Metal Stargate/Mass Effect relay to the point where it obliterated Thanagar. He himself was twisted by Nth Metal in the process, growing his own pair of tarnished gold-and-bronze batwings. Now a monstrous shell of his former self, he swore to hunt down all remaining Thanagarians to the ends of the universe--and he went past those ends. Into our universe.

And that was where he slaughtered Oren's team.

To this day, Oren couldn't tell you why, exactly, he survived. Some might theorize that because Batman, regardless of the universe, uses fear as a tool, he needed to leave someone alive to tell the tale, to strike fear through all the Thanagarians of this universe. But Oren fears the truth is something much worse. He remembers a terrible dream as he lay bleeding out on that lonely asteroid. He remembers sinking into darkness, and something in that endless dark claiming him for a greater purpose.

Oren awoke on an unfamiliar ship with bandaged wounds, though was disturbed to notice that his wounds did not seem as dire now as they had when he was attacked by the Hawkbat. He soon found that he had been rescued by the Omega Men, a ragtag group of Space rebels sworn to fight the oppressive reach of the Citadel. Figuring that, as far as the Thanagarian empire knew, he was dead, and also more sickened than ever at the aspect of empire itself, he decided to join in their fight.

Oren's stint with the Omega Men ended up pretty short-lived, though, as he found himself frequently butting heads with the Omega Men's other newest and youngest member (as well as his actual rescuer), Aleea. Aleea was already on thin ice because her parentage basically painted a target on the Omega Men's back, though this was kept a secret from Oren as well for as long as possible.

So when Oren discovered, and in the process accidentally revealed in a crowded spaceport that Aleea was in fact Aleea Strange, the half-human half-Rannian hybrid and the Granddaughter of Rann's chief scientist, Sardath, the Omega Men basically cut their losses and ditched both Oren and Aleea on earth.

And that's where they are now! Both pissed off at each other, both fishes out of water, and now, possibly, our newest defenders against interstellar and dark multiverse threats! (If they can stop bickering long enough to stay alive...) What adventures lay ahead of them? Will Rann and Thanagar ever be able to resolve their bloody and distrustful history? Will Earth ever be a home?! Time will tell!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are models for the proposed terraforming of Mars which involve the use of lichens and similar organisms to transform the soil and atmosphere. There's something fascinating about entire strains of living things reproducing and dying for the sake of humanity's own propagation. This is the reduction of entire species of life to a sort of instrumentalism, and there is a horror to that.

There is a (primarily but not exclusively american) cultural cohort who I will call for the purposes of this list the astro-futurists. They are strong proponents of space colonization, frequently for the purposes of building humanity's resilience against supposed "x-risks", such as asteroid strikes or sapient computers that we are unable to control. Even if Earth dies, humanity will live on on martian soil and around the stars of Alpha Centauri!

There is a certain type of high school 'nihilist' who has no philosophical groundings for his works, but has a primitive understanding of Darwinism, and so concludes that the purpose of all life is to reproduce. In the most base sense, he is correct; all extant life is shaped by the need to pass on its genetic material. Most people would say this is reductive, however, and they are correct too.

The lichen would not be the first thing humanity has bent to specific purposes like that. Billions of chickens are kept in factory farms for the sake of meat and egg production, and so their lives are similarly reduced to a singular purpose in the service of humanity. In the reductive eyes of the high schooler, who views procreation as the highest virtue of life, humanity has done these chickens a great favour! While disease and predators might threaten populations of junglefowl in the wild, the structure of the farm protects the chickens from predators, and judicious cullings ensure that some part of the population will always be resilient against disease. Even as humanity kills the chickens for their meat, we ensure that there will always be another chicken.

The chicken is, therefore, the immortal junglefowl. Bar a vast reorganization of human civilization, the domestic chicken will last as long as humanity does. The genes which distinguish them from their wild relatives will propagate forever, just as the lichens humanity plants in the martian soil will have a monopoly on that soil, free of the rival strains of lichen which populate the earth. No one, however, looks at a factory farm and says "How charitable of humanity to make these birds immortal!" Why is this?

The most existentially concerned of the astro-futurists might consider the cultural and social development of space travel, like their more idealistic peers, but ultimately their prerogative is the survival of humanity against any threat which might render Earth uninhabitable. Some have criticized these efforts as a new form of colonialism to further enrich the global north, and note that the countries most capable of creating space colonies are those mostly strongly integrated into the capitalist system. The first flag on Mars will in all likelihood be that of the United States, or that of whichever ascendant capitalist power who succeeds them.

There are two problems with the existential programme of the astro-futurists, beyond the ways in which it unduly advantages the global north. The first is that Mars, and indeed much of space, is a terrible home for humans. Those who live there will suffer from radiation, and poisonous dust, and will likely reside in cramped underground dwellings. The lower gravity will cause their bones and flesh to atrophy, and should they have children on Mars, there is a good chance their young will never return to the home of their parents, lest Earth's gravity crush their feeble lungs and hearts. These lives will be bold and novel, entirely distinct from those of all humans before them, but they may not be enviable.

The second problem is that, even assuming that Mars somehow becomes wholly self-sufficient of Earth, in the event that Earth is destroyed, Mars will not save humanity. A narrow slice of the cultures of the global north will be salvaged by the Martians, perhaps. English will still be spoken, but the hundreds of languages of Africa will likely perish. Recorded music will survive, but the little regional songs no one thought to record will not. This is the survival of humans, not of humanity.

The notion of 'memes' is sometimes attributed to Richard Dawkins, a man with a complicated legacy not worth discussing. I have heard rumour that the idea originates from somewhere else, however. If one takes the traditional formation of memes to be true, then astro-futurism can be considered a sort of meme or collection there, as can its more existentially-concerned strains. If we settle Mars to survive the loss of Earth, then perhaps humanity will die and this meme will continue to propagate. What remains will become another example of the instrumentalization of life, with a vast complexity of experiences reduced, ultimately, to the ability to serve the propagation of others.

#just some ideas#perhaps this is what i believe#perhaps not#i do hope we get up an o'neill cylinder in my lifetime#but i very much doubt we will

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"okay but just because it's called colonization doesn't mean it's actually bad in any similar way to the way intra-earth colonization efforts were right?" strictly speaking, no, but its indicative of the logic in play that would desire the selling pitch of space colonization to begin with; the promise of an infinite pool of resources that we can milk out with no ethical or environmental concerns on our end, allowing us to not only keep our presently wildly unsustainable society but to expand it tenfold. the promise of a true terra nullis that can keep the consumer products coming forever and ever without the subsequent reports of devastation. the pitch of this is always ofc with the promise that the horrific scenes of terran mining will come to an end, but the pitch is not inherently about ending mining on earth, its about expanding it to space. thats a very important distinction to make, because before we start gutting luna for parts, the materials to create spacecraft must come from here, the materials to produce mining equipment must come from here, the launch sites for the spacecraft must be on here, and the exhaust from rocket launches will be within earth's atmosphere. the promises of space mining only start to pan out well into its operation, before that, the level of resource extraction on earth must intensify, not decline. all of these little projects that the u.s and chinese govts are working on abt hypothetical mining operations in the 2030s or 2040s or whenever are not alternatives to their dependency on colonial peripheries for resource extraction but a means to greatly expand it.

thats what im interested in, the transitional window between our current state of terran mining and the promised pay-off of ending all mining on earth, because its in that window that we see the continuity of logic here as well as the price we are going to pay for that pay-off. we already reduce lands to terra nullis, we already strip mine large swathes of land that we have deemed to be uninhabited and or undesirable, we already have the assumption that we can keep doing that to more and more land for as long as we will, and we are justified in doing so because our society needs - no - deserves the incomprehensible amount of riches that come from it. its just that we're stuck doing that on earth. that the moon in many ways actually fits this description (i object to this but thats more on the level of high minded "actually we shouldnt treat any land as if it were worthless" beliefs and not helpful to this convo) doesnt negate the fact that this is just extending the extractivist logic, a logic that is presently strip mining the earth and destroying the biosphere. a lunar mine that gives us all an ocean of precious metals is still a great many decades away, and until then, its coming out of our planets pockets, and it will be mined by the same companies and same governments in the same designated sacrifice zones by the same workers, and it just so happens that those zones are overwhelmingly colonial peripheries.

its a bit hard taking the condescending rebuttals of anti-space colonization arguments by the astroleninists seriously when the entire politics and discourse of space colonization is so thoroughly rooted in colonialist logic and ideology that we, well, refer to it as "colonization" by default. i dont think thats a coincidence

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading the last part of Shamus Young’s big Mass Effect review, where they talk about Mass Effect: Andromeda... I haven’t played the games, but it sounds to me like Andromeda didn’t follow a potentially interesting aspect of its premise.

The Andromeda galaxy doesn’t have Reapers, right? So what does a galaxy where death robots don’t kill everybody every 50,000 years look like?

Imagine going from a setting that’s kind of like Star Trek with more alien aliens to a setting that’s kind of like David Brin’s Five Galaxies civilization. Or, to put it another way, imagine going from a setting that’s kind of like Star Trek to a setting that’s kind of like a mix of the Star Wars Galactic Empire and the Orion’s Arm Terragen Sphere. Just this tremendously vast and old civilization, because in Andromeda there are no Reapers so civilizations actually get a chance to flourish and grow and develop for more than an eyeblink in cosmic time. It wouldn’t necessarily even have to be technologically super-advanced, just huge because civilization has had so much time to spread.

Maybe have the colonists arrive during a Dark Age, so they can still be a locally significant faction instead of just a curiosity. The antagonists of the game could be the local pirates and post-apocalyptic warlords. Shamus Young had a “how I’d have done it” idea I like that would mesh well with this with only a small modification.

One idea, inspired by this: instead of the colonists having trouble because the worlds they intended to settle are less habitable than they expected, they have trouble because more-or-less every nice planet is already inhabited. The Milky Way is mostly empty because civilization gets razed every 50,000 years, but in Andromeda civilization has been growing and spreading for so long that most nice worlds in the galaxy have been colonized (which implies billions of inhabited worlds and a galactic population in the quintillions or more). Andromeda looks like Earth, where basically all habitable land already has people on it and most of the true Terra Nullius you’re going to find is the equivalent of Antarctica (Mars-like worlds, airless moons, etc.).

Maybe one of the big decision points in the game could be something like this:

You have surveyed all worlds within 40 light years. This region of Andromeda seems to be thickly inhabited; of the 78 habitable worlds within that volume, 68 are already inhabited. You must choose between these options:

1) The surveys have revealed 9 marginally habitable worlds that remain uninhabited. These include ocean worlds with small islands the only land, desert worlds with only small seas and vegetated areas, etc.. You may choose to settle these. While some of these worlds would be habitable enough in the short term, a few centuries of plausible population growth would render them cramped homes for any new society.

2) The survey has revealed one very habitable and lush world that remains uninhabited. Ancient beacons mark this world as having a status in the Old Empire similar to a national park; it was set aside to remain uncolonized, as a gift to the future or to any intelligent species which might one day evolve on it. The message implies this policy was in continuity with a practice that far pre-dated the Old Empire, and a number of huge monuments in varying locations around the planet, its moon, and in orbit of the planet suggest this may be the case, although we cannot read the text on the older monuments. The oldest of these monuments is a skyscraper size monolith that stands on the summit of the highest mountain of the planet’s airless moon, and analysis of micrometeorite erosion suggests it may be over seventy million years old. The world has remained uncolonized because of the reverence this law is held in even after the fall of the Old Empire. You may choose to settle this world; the survey team has thoroughly checked for ancient defense systems and other dangers and found none, and it is a rich world which would provide an excellent home for Humans or other species with similar environmental needs. The only apparent worry is alienating the neighbors - though of course with the disclaimer that there is still much you do not know about this galaxy.

3) You may attempt to liberate some of the worlds ruled by some of the nastier warlords and settle the colonists on them. It would not be difficult to offer the locals a better deal than some of these warlords, which should win their cooperation in the short term. The colonist population is small enough that it would not greatly burden an already inhabited world with a sizable population in the short term. While settling on an already inhabited world has obvious risks and disadvantages, it would also mean gaining access to pre-existing infrastructure instead of having to build it, as well as gaining access to a labor force much bigger than the colonist population. The obvious risk is, well, the obvious bad places that “settle on a world that already has people on it” might lead.

4) You may send survey teams farther afield to try to find more empty habitable worlds. The risk is there’s no guarantee you’ll have better luck elsewhere, sending out survey probes and expeditions uses up resources, and the colonists are burning through supplies while they wait for the survey teams to find new homes for them.

5) You may attempt to establish air-sealed colonies on various uninhabited barren worlds and/or convert some of the Arks into self-sufficient space habitats. Upside is you’ll have plenty of empty asteroids, airless moons, etc. to choose from. Downside is the technological challenges of establishing a society of this type will be formidable and if you fail everyone might die, maybe too quickly to make any attempt to change strategy. The prospect of spending the rest of their lives in a sealed artificial habitat may also lower colonist morale and generate political resistance.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Simulations reveal the most likely place for a galactic civilization in the Milky Way

https://sciencespies.com/space/simulations-reveal-the-most-likely-place-for-a-galactic-civilization-in-the-milky-way/

Simulations reveal the most likely place for a galactic civilization in the Milky Way

The Milky Way is 13 billion years old. Some of our galaxy’s oldest stars were born near the beginning of the Universe itself. During all these eons of time, we know at least one technological civilization has been born – us!

But if the galaxy is so ancient, and we know it can create life, why haven’t we heard from anybody else?

If another civilization was just 0.1 percent of the galaxy’s age older than we are, they would be millions of years further along than us and presumably more advanced. If we are already on the cusp of sending life to other worlds, shouldn’t the Milky Way be teeming with alien ships and colonies by now?

Maybe. But it’s also possible that we’ve been looking in the wrong place. Recent computer simulations by Jason T. Wright et al. suggest that the best place to look for ancient space-faring civilizations might be the core of the galaxy, a relatively unexplored target in the search for extra terrestrial intelligence.

youtube

Above: Animation showing the settlement of the galaxy. White points are unsettled stars, magenta spheres are settled stars, and white cubes represent a settlement ship in transit. The spiral structure formed is due to galactic shear as the settlement wave expands. Once the Galaxy’s center is reached, the rate of colonization increases dramatically. (Credit: Wright et al.)

The Churn

Older mathematical models of space colonization have tried to determine the time required for a civilization to spread throughout the Milky Way. Given the size of the Milky Way, wide-scale galactic colonization could take longer than the age of the galaxy itself.

However, a unique feature of this new simulation is its accounting for the motion of the galaxy’s stars. The Milky Way is not static, as assumed in prior models, rather it is a churning swirling mass. Colonization vessels or probes would be flying among stars that are themselves in motion. The new simulation reveals that stellar motion aids in colonization contributing a diffusing effect to the spread of a civilization.

The simulation is based on previous research by Jonathan Carroll-Nellenback et al. which proposed that a hypothetical civilization could spread at sub-light speeds through a moving galaxy. The simulation assumes a civilization using ships travelling at velocities comparable to our own spacecraft (about 30 km/s).

When a ship arrives at a virtual habitable world in the simulation, the world is considered a colony and can itself launch another craft every 100,000 years if another uninhabited world is in range.

Simulated space craft range is 10 light years with maximum travel duration of 300,000 years. Technology from a virtual colony was set to last 100 million years before dying out with the opportunity to be resettled should another colony drift into range by galactic motion.

The results are dramatic. The galaxy’s rotation generates a wave or “front” of colonization. Once the front reaches the galactic core, the core’s density catalyzes a rapid increase in the rate of colonization. Even with very conservative limits placed on the speed of the space craft, a majority of the galaxy could be colonized in less than a billion years – a fraction of its total age.

Line of Sight

The simulation’s results reaffirm past proposals by Vishal Gajjar et al. to search the galactic center for signs of life. Not only can the center of the galaxy be rapidly colonized, but also efficiently scanned for technology.

We have a direct line of sight to the galaxy’s center which encompasses the densest region of space relative to us. And since the galaxy formed from the inside out, the center is filled with older planets which provide more time for life to evolve.

The center also serves as a logical place to “talk” to and from – a central focal point of the galaxy. If you wanted to get a signal out to the rest of the galaxy, you could do so from the center to blanket the disk of the Milky Way. Likewise, if you wanted to find a signal, you might look to that same center.

Gajjar et al. also hypothesize that an advanced civilization may be capable of tapping into the energy of the Milky Way’s central supermassive black hole to power a galaxy-wide signal beacon. Talk about a powerful “hello!”

A view toward the galaxy’s center from Earth captured in the Mojave Desert. (Matthew Cimone)

Then Why so Quiet?

Still, none of this answers the previous question – where are they? In fact, the speed at which the galaxy could be colonized complicates why we haven’t heard from anybody.

Furthermore, Caroll-Nellenback et al. also note that during colonization, an advanced civilization might develop new propulsion technologies shortening the time needed to spread. And yet, preliminary radio scans of the galactic core haven’t revealed any signals.

Perhaps the silence itself is an answer. The galaxy is so old with so much time available for life to spread that some believe the silence dooms any hope of meeting anybody.

But there is still hope!

The simulation shows it’s possible that some parts of the galaxy are never settled despite eons of time. It’s a matter of efficiency. Remember, you want to colonize at the shortest possible ranges.

As time passes, some colonies die out and are lost perhaps from resource exhaustion or cataclysmic event. Rather than reach farther out into space, colonies choose to reinhabit a dead colony at closer range.

Clusters of inhabited colonies form surrounded by uninhabited planets that are never colonized. A “steady state” is achieved where regions of the Milky Way’s habitable worlds are simply too inefficient to colonize.

There are other possibilities to explain the silence as well. Perhaps long-lived civilizations are governed by sustainability to grow more slowly than anticipated. If there are multiple colonizing civilizations perhaps they are competing for resources or keep a distance from each other.

Perhaps civilizations take care to not interfere with inhabited planets such as ours (similar to the Prime Directive in Star Trek) or are cautious of potential biological incompatibilities faced on other worlds. All these possibilities may explain why we have yet to meet anyone… unless we already have… no, seriously.

A Buried Past

Carroll-Nellenback et al. consider a “temporal horizon” – a point in history beyond which Earth would no longer retain evidence of previous colonization. Let’s say, for example, a galactic alien civilization landed on Earth billions of years ago, lived thousands of years, then died off.

After all this time, virtually no evidence would remain of their presence. So “we” haven’t met an alien civilization, but it’s possible Earth itself has.

The simulation shows that, given our location in the galaxy, there is an 89 percent likelihood that at least a million years could pass without visits from interstellar ships – potentially enough time to erase signs of previous colonization.

The point is that between the galaxy being completely colonized, or being completely empty, the simulation demonstrates that there can be middle grounds – valid responses to the silence which still leave room for technological extraterrestrial life even without contact.

Globular Life?

While the center of the galaxy is an ideal future realm for SETI research, there are other regions of the galaxy which mimic the same favorable conditions as the center – globular clusters.

Globular clusters (GC) are ancient massive collections of stars orbiting about the center of the galaxy at distances of tens of thousands of light years. Relics from a period of intense star formation catalyzed by galaxy mergers, there are about 150 known GCs in the Milky Way ranging from 10-13 billion years old.

youtube

GCs are incredibly dense with stars much closer to each other on average than found in the disk of the Milky Way. When considering interstellar travel or communication, we are typically talking about millennia.

However, a civilization within a GC would experience travel time between stars on the order of just a few years with communication times of months or even weeks. Problem is that the densities of GCs may negatively impact planet formation as well as the orbital stability of planets.

R. Di Stefano and A. Ray calculate what they call a “GC habitable zone”. We generally use the term “habitable zone” to describe the distance a planet needs to orbit a star to maintain temperatures for liquid water. Earth resides in the habitable zone of the Sun (good thing for us). Rather than a 2 dimensional radius like the orbit of a planet, a GC habitable zone is a three dimensional shell orbiting around the center of the cluster itself.

The inner part of the shell’s thickness begins where the GC density drops to where solar systems can survive the gravitational interference of nearby stars. The gravity of a nearby star might pull apart planetary dust rings disrupting the creation of planets. Another star passing near a system could also eject a planet from its parent star.

The outer edge of the shell’s thickness is defined by where the density becomes so low that the average distance between stars is greater than 10,000 AU (astronomical units, representing Earth’s distance from the Sun at about 150,000 km). 10,000 AU is equal to about 2 light months.

After this point, the advantages of being in the cluster – namely the short travel and communication times to neighboring stars – diminish. The zone encompassed by the shell is what Di Stefano and Ray call the GC “sweet spot” for colonization – star systems that are close together facilitating quick travel/communication but not so close that they tear each other’s systems apart.

We want the GC sweet spot to encompass mainly lower mass stars which live the longest. Serendipitously, low mass stars also have the smallest radius solar habitable zones. The closer a planet orbits its parent star the less likely it is of being torn away by another star.

Globular cluster M13. (Howard Trottier/SFU Trottier Observatory)

GCs also experience a phenomenon called “mass segregation” where the most massive stars – and therefore the least favorable to habitability in the cluster – find themselves gravitationally drawn toward the center. This segregation then naturally sorts the cluster from least to best choice systems from core to periphery.

The results are favorable. In a hypothetical GC approaching 100,000 solar masses, the sweet spot encompasses 40 percent of G stars (yellow dwarfs like our own Sun) and 15 percent of K and M stars (orange and red dwarfs) in the cluster. That’s a lot of stars.

There is even the possibility that planets which have been ejected from systems could still host a civilization because of the combined ambient energy the planet receives from all the stars in the cluster – especially if the civilization has advanced solar energy capture technology. A free-floating world of space aliens.

Just throwing out numbers, Di Stefano and Ray suggest that even if only 10 percent of GC stars have habitable planets, 1 percent of those support intelligent life, and 1 percent of those host a communicating civilization, at least one communicating civilization could exist in every GC in the Milky Way.

Similar variables assigned to the Milky Way itself – with far lower stellar density – would result in… one communicating civilization (probably us). Changing the percentages to be slightly less conservative would mean more civilizations could exist in the diffuse disk but would be separated by massive distances upwards of 300 light years.

If you were located in a GC, you may try to communicate with the distant disk of the Milky Way. We, unfortunately, have yet to find any direct evidence that planets even exist in GCs. Our techniques for finding exoplanets are impaired by the distance to and densities of GCs. But that doesn’t rule out the possibility. If a civilization does exist in a GC, with quick access to thousands of stars, Di Stefano and Ray say the civilization would essentially be “immortal.”

We’ve actually beamed a message to a GC – the beautiful M13 Hercules globular cluster. Located in the constellation of Hercules, the cluster is 22,000 light years away, 145 light years in diameter, and is comprised of about 100,000 stars.

In 1974, a message was sent to M13 from the Arecibo radio telescope (RIP). The message contained the numbers 1 to 10, chemical compounds of DNA, a graphic figure of a human, a graphic of the solar system, and a graphic of the radio telescope itself. Total broadcast time was 3 minutes. Still has a few thousand years to get there.

Likely the low resolution message won’t be discernible by the time it arrives at M13. But perhaps one day we will make contact with a galaxy-spanning civilization. Or, perhaps WE will become a galaxy-spanning civilization. For that story, I’m eagerly awaiting the upcoming screen adaptation of Asimov’s Foundation series!

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.

#Space

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sorry, Cassandra.

So, it's definite then

It's written in the stars, darlings

Everything must come to an end - Susanne Sundfør

I first learned about the climate crisis in 2008, as an undergrad at Hunter College, in a class called The History and Science of Climate Change. For the next decade I would struggle with how to process and act on the scientific paradigm shift climate change required: that human activity could disrupt the climate system and create a planetary ecosystem shift making Earth uninhabitable to human life. I became a climate justice activist and attempted to work directly on The Problem which was actually, as philosopher Timothy Morton writes, a hyperobject, something so systemic and enormous in size and scope as to be almost unintelligible to human awareness. I’ve cycled through probably every single response a person could have to this knowledge, despair, ecstasy, rage, hope. I’ve landed somewhere close to what I might call engaged bewilderment. For me, his particular locale has a soundtrack, and it’s Susanne Sundfør’s cinematic dance dystopia Ten Love Songs, an album that tells a story of love and loss in the Anthropocene. Sundfør is a sonic death doula for the Neoliberal project, with a uniquely Scandinavian version of bleak optimism. To truly grapple with this time of escalating transition, we need to really face what is, not what we hope or fear will be, but what is actually happening. A throbbing beat with shimmering synths around which to orient your dancing mortal envelope can’t hurt.

Susanne Sundfør’s Ten Love Songs was released a few days after Valentine’s Day in February of 2015, six months after I had been organizing Buddhists and meditators for the Peoples Climate March. I was already a fan, having first heard her voice as part of her collaboration with dreamy synth-pop outfit m83 on the Oblivion soundtrack. Oblivion was visually striking but felt like a long music video. The soaring synths and Sundfør’s powerful voice drove the plot more than the acting, though I loved how Andrea Riseborough played the tragic character Vika, whose story could have been more central to the plot but was sidelined for a traditional Tom Cruise romantic centerpiece. But since the movie was almost proud of its style over investment in substance, the music stood out. The soundscapes were as expansive as the green-screened vistas of 2077 in the movie. It was just nostalgic enough while also feeling totally new, a paradox encapsulated in the name of m83’s similarly wistful and sweeping Hurry Up, We’re Dreaming. I am not exempt from taking comfort in style that signifies a previous era, and I am also not alone in it. It’s a huge industry, and while the MAGA-style yearning for a previous era is one manifestation, maybe there are ways to acknowledge culture as cyclical in a way that doesn’t sacrifice traditional knowledge to some imagined myth of perpetual progress.

When Ten Love Songs came out the following year, I listened to it on repeat for days. Sundfør seemed to have absorbed the music-driven sci-fi into a concept album, with m83 providing her with a whole new panopoly of sounds at her disposal. Like Oblivion, Ten Love Songs told the story of a future dystopia with high speed chases, nihilistic pleasure-seeking and operatic decadence against a backdrop of technocratic inequality. It mixed electro-pop with chamber music and I listened to it on a Greyhound ride to Atlantic City in the middle of snowy February. I hadn’t felt like this since high school, that a full album was a sort of soundtrack to my own life, which I could experience as cinematic in some way while the music was playing. This situated me in my own story, of studying climate change as an undergrad and graduating into a financial collapse, working as a personal assistant to an author writing about ecological collapse and ritual use of psychedelics, to joining a Buddhist community and organizing spiritual activists around climate justice.

Ten Love Songs is a breakup album, with lyrics telling of endings and running out of time. But it didn’t read to me as an album about a single human romantic relationship coming to an end. It felt like a series of vignettes about the planet and its ecosphere breaking up with us, all of us. People. Some songs like Accelerate, one of the album’s singles, throb in an anthem to nihilistic numbness and speeding up into a catastrophe that feels inevitable. Fade Away is a bit lighter, tonally and lyrically, (and if you listen, please note the exquisitely perfect placement of what sounds like a toaster “ding!”), but is still about fading away, falling apart. The way the songs seem to drive a narrative of anthropocenic collapse built on science fiction film scores, the combination of orchestra and techno-pop, absolutely draws on Sundfør’s experience collaborating with m83 for the Oblivion soundtrack, which itself combined Anthony Gonzalez’s love for the adult-scripted teen dramas of his own 80’s adolescence. In Ten Love Songs, Sundfør takes what she learned from this collaboration and scores not a movie but a life experience of living through ecological collapse and all of the heartbreak and desire that erupts in a time when everything seems so close to the knife’s edge.

I am reminded of another Scandinavian dance album that was extremely danceable yet harbored within it a sense of foreboding. The Visitors, ABBA’s eighth studio album, was considered their venture into more mature and complex music. The two couples who comprised the band had divorced the year before it was released, and the entire atmosphere of the album is paranoid, gloomy, and tense. The cover shows the four musicians, on opposite sides of a dark room, ignoring each other. Each song is melancholy and strange in its own way, unique for a pop ensemble like Abba. One song in particular showcases their ability to use an archetype of narrative tragedy and prophesy to tell the story of regret. Cassandra is sung from the perspective of those who didn’t heed the woman cursed by Zeus to foretell the future but never be believed.

I have always considered myself a pretty big Abba fan, something my high school choir instructor thought was riotously funny. I was born in the 80’s and nobody in my family liked disco, so I seemed like something of an anachronism. But pop music, especially synth-oriented pop, has always felt like a brain massage to me. It could get my inner motor moving when I felt utterly collapsed in resignation to the scary chaos of my early life. But I only discovered the song Cassandra in 2017, while giving The Visitors a full listen. It felt like I had never heard the song before, though, as a fan I must have. But something about 2015 made the song stand out more. It starts with piano, soft tambourine, and the ambient sound of a harbor. It has a coastal Mediterranean vibe, as some Abba songs do, foreshadowing Cassandra’s removal from her home city, an event she foretold but could not get anyone to believe. It’s a farewell song of regret, echoing the regret the members of Abba felt about their own breakups.

We feel so full of promise at the dawn of a new relationship. Only after the split can we look back and say we saw the fissures in the bond. The signs were there. Why did we ignore them? This happens on an individual level but the Cassandra paradox is an archetype that climate scientists and journalists are very familiar with. This particular Abba song, and the Visitors album overall, uses this archetype to tell the story of a breakup in retrospect. With climate change, the warnings have been there, even before science discovered the rising carbon in the atmosphere. Indigenous peoples have been warning of ecological collapse since colonization began. Because of white supremacy and an unwavering belief in “progress,” perpetual economic and technological development and growth, warnings from any source but especially marginalized sources have been noise to those who benefit from that perpetual growth model and from white supremacy itself. Is there a way to undo the Cassandra curse and render warnings signal BEFORE some major event turns us all into the chorus from Abba’s song, singing “some of us wanted- but none of us could-- listen to words of warning?” Composer Pauline Oliveros called listening a radical act. It is especially so when we listen actively to the sounds and signals of those we would otherwise overlook.

When I look back at my life in the time that Sundfør’s Ten Love Songs and m83’s movie music seems nostalgic for, the late 1980’s in New Jersey, I was a child with deeply dissociative and escapist tendencies, which helped me survive unresolved grief, loss, and chaos. I recognize my love for Abba’s hypnotic synth music as a surrendering to the precise and driving rhythm of an all-encompassing sound experience. I also see how my early life prepared me to be sensitized to the story climate science was telling when I finally discovered it in 2008. I had already grown up with Save the Whales assemblies and poster-making contests, with a heavy emphasis on cutting six-pack rings so that sea life would not be strangled to death. I knew what it was like to see something terrible happening all around you and to feel powerless to stop it, because of the way my parents seemed incapable of and unsupported in their acting out their own traumatic dysregulation. Wounds, unable to heal, sucking other people into the abyss. I escaped through reading science fiction, listening to music like Abba and Aphex Twin loud enough to rattle my bones. I wanted to overwhelm my own dysregulated nervous system. I dreamed of solitude on other planets, sweeping grey vistas, being the protagonist of my own story where nothing ever hurt because ice ran through my veins and the fjords around me. My home planet was dying, and nobody could hear those of us screaming into the wind about it.

Ten Love Songs woke up that lost cosmic child who had banished herself to another solar system. Songs of decadence, songs of endings, songs of loss. Though that album was not overtly about climate change, Sundfør did talk about ecological collapse in interviews for her radically different follow-up album Music For People In Trouble. After the success of Ten Love Songs, Sundfør chose to travel to places that she said “might not be around much longer” in order to chronicle the loss of the biosphere for her new album. It is more expressly and urgently about the current global political moment, but the seeds for those themes were present and in my opinion much more potent in the poppier album. But maybe that’s the escapist in me.

The old forms that brought us to this point are in need of end-of-life care. Capitalism, white supremacy, patriarchal theocratic nationalism, neoliberalism, they all need death doulas. Escapism makes sense in response to traumatic stimulus, and for many of us it may have helped us survive difficult circumstances. But if we are to face what it means to be alive on this planet at this moment, we might be here to be present to and help facilitate and ease the process of putting these systems to rest. And maybe this work is not at odds with a dance party. The ability to be visionary about shared alternatives to these dying systems is not inherently escapist, when we are willing to take the steps together to live into those new stories. What would happen if cursed Cassandras, instead of pleading with existing power structures to heed warnings that sound like noise to them, turned to each other to restore the civic body through listening, through bearing witness to each others unacknowledged and thwarted grief over losses unacknowledged by those same systems of coercive power?

Engaged bewilderment means my version of hope, informed by Rebecca Solnit’s work on the topic, comes from the acceptance that things will happen that I could never have imagined possible. Climate change is happening and there are certain scientific certainties built into that trajectory. Some of it is written in the stars. But as with any dynamic system change, we do not know exactly how it will all shake out. These unknowns can be sources of fear and despair, but there is also the possibility for agency, choice and experimentation. The trajectory of my individual life was always going to end in death. Does that make it a failure? Or does it render each choice and engagement of movement towards the unknown an ecstatic act? As the old forms collapse, no need to apologize to the oracles. At this point they are dancing, and hope you’ll join.

#susanne sundfør#abba#anthropocene#hope#climate crisis#climate change#ecological collapse#scandinavian music#dystopia#utopia

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Space Colonization beyond the Earth Sphere

Meta by AngelT (published in Rhythm Generation Zine, 2019)

Disclaimer: No money is made in the research and production of this presentation. This was part of a team-based project. The contents presented in this essay are inspired by Mobile Suit Gundam Wing, which is the sole property of Sotsu, Sunrise and their affiliates. Also, an appreciation for the Universe beyond Earth’s atmosphere; the science of astronomy is beautiful.

Most of us who grew up back in the day recall witnessing space stations, satellites and colonies on our television screens. We’ve seen human life preserved beyond the Earth’s sphere in space colonies. Our beloved characters, including The Mad Five and members of The Alliance, have acquainted themselves with continuing the trend of political stability, health and wellness, education, housing, and industry—miles away from our planet amidst warfare. Today, scientists are researching the possibility of colonizing the Solar System, beyond Earth and the Moon.[1]

Predicting Colonization in CE 2030

During the events of the television series, we see that a lunar station exists. This is a distinct possibility for Earth in the coming years, and it’s not hard to imagine small businesses and corporations operating from there in the future. Prior to launching the official project, however, extensive training and preparatory exercises would be a requirement. Relocating to the Moon comes with risks, considering the physical attributes of the location. Even so, there’s a good chance humans will one day be able to survive for extended durations in space. Scientists and researchers today are working towards opening the doors of opportunity. But successful expansion into the solar system has everything to do with timing, how well we can put knowledge into practice, and overcoming challenges such as limited funding, support from governments and health risks associated with living off of Earth.

Weighing the Odds: Inner Space

Mercury would be fun (imagine seeing your next birthday every 88 Earth days). Unfortunately, that will require a lifetime supply of sunblock and water—both of which will be hard to maintain on-planet. Mercury’s orbit is closest to the Sun, where it experiences a stronger gravitational pull from the sun than other planets in the solar system. In addition, although a year is significantly shorter than on Earth, Mercury’s days last significantly longer (roughly 176 Earth days) due to its slow rotation. Combined with the naturally shorter year, colonists on Mercury would experience a quicker aging process compared to life as we know it on Earth. The proximity to the sun would require measures to be taken to limit sun exposure, and extreme fluctuations in temperatures—made worse by the lack of an atmosphere which would have otherwise helped regulate them—make Mercury less than ideal for human colonization.

Venus is the same size as Earth and its orbit is within the “habitable zone,” a safe enough distance from the sun; however, like Mercury, Venus has a significantly longer day (roughly 116.75 Earth days) and has a shorter year (almost 225 Earth days) which will cause similar stresses on any colonists looking to find a home on-planet. Venus’s atmosphere is not only incredibly toxic but also extremely dense with a surface pressure of nearly 92 times that of Earth’s. This dense atmosphere also means that the planet is hotter than Mercury (surprise!) limiting its chances of being particularly hospitable to humans. For these reasons, it’s best to keep would-be colonizers off-planet. Unfortunately, Venus also has no known moons, so using satellites as was done with Earth’s moon isn’t an available alternative. Therefore, pursuing a space colony project for Venus isn’t recommended.

Mars has been a hot topic for NASA and its affiliates since the late 1970s. Based on results from space probes that captured the red planet’s features, there’s a thin line of similarities to Earth: what many assume to be waterways, ground that is similar to Earth’s soil, and glaciers at the poles. Mars’s two moons, Phobos and Deimos, present an opportunity for additional lunar bases, which will benefit a population who relocates to Mars by providing additional space for industry, employment, and lodging. However, anyone who wishes to relocate to the planet should also expect two seasons—Summer and Winter—until the planet can be properly terraformed with an atmosphere able to support human life.

Weighing the Odds: Outer Space

Jupiter is a gaseous planet, the biggest in the solar system, and its volatile beauty is due to the multitude of storms travelling across its surface (similar to what we know as tornadoes and hurricanes). Such a volatile surface would deter on-planet colonization. But if researchers were to approach colonization from a practical standpoint, there’s a good chance lunar bases could be built on one of Jupiter’s moons. The moon Europa, for instance, has garnered attention from astronomers due to the possibility that it could support life if conditions were right. There is a serious threat of radiation from Jupiter’s magnetosphere, which is 20,000 times stronger than that of Earth’s, that poses serious challenges for colonizing both the planet and the moons.

Saturn, another gas giant, presents similar challenges, and humans are better served by colonizing one of its sixty-two moons instead. Protection from radiation will be needed. One of the best routes to carry out this mission is on Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, which is a ball of ice, with water. Titan’s icy layer can protect from the Sun’s rays and drilling the surface will intrigue anyone familiar with mermaids and Atlantis. Although Titan’s air pressure would allow someone to walk the surface without a spacesuit, the atmosphere is low in oxygen compared to Earth’s own and it is bitterly cold. To colonize it, ongoing research and developing technologies will help. Wearing specialized clothes that have the same attributes as space blankets, earbuds that protect the eardrum (in the middle ear) from shifting due to air pressure changes, and architecture designed for underwater environments is a starting point.

Uranus, another gas giant, does not have a breathable atmosphere, consisting primarily of hydrogen (outer layer) and helium. This planet is also the coldest in the entire Solar System, which is roughly -216°C. Unfortunately, the moons of Uranus are pure ice, with intolerable temperatures below -200°C. Although Miranda has various landscapes similar to Earth’s, colonization cannot currently happen. It will take several decades for engineers and scientists to come up with some alternatives: Heated clothing, mirrors that support solar energy, and SMART technology that supports temperature control. A terraforming project also needs to be in effect. Otherwise, living near Uranus is not recommended.

During the early 1990s, Neptune had a Great Dark Spot where powerful wind storms were consistent. Neptune rotates on its axis at a rapid pace, which makes it uninhabitable. Astronomers know Triton is Neptune’s biggest moon, but there’s a major safety hazard. On multiple occasions, Neptune has collided with other orbital bodies (hence its rings). Because of this, building satellite colonies is not the best route. Triton could crash and end up as remnants to Neptune’s ring supply; colonies near this planet present a grave risk to human life.

Pluto[2] has five moons that can serve as optimistic colonizers. But methane and nitrogen don’t offer a livable space for humanity. It’s the farthest from the Sun; a twinkling star in the sky even through a telescope. Colonization in orbit needs technological advancements first, such as lights that emit heat energy, specialized mirrors, and lifelong oxygen supply. Industrial workers can use Charon (Pluto’s largest moon) for lodging, business and trade markets. To colonize Pluto means living off-planet, but its temperatures and distance from the Sun (5.9 billion kilometres) present complications.

Closing Thoughts

Although each planet offers unique challenges to overcome for colonization, there are some things that are consistent across the whole solar system:

1. Colonization needs to figure out how to protect from solar and space radiation. Radiation has proven to have debilitating effects on our bodies (dehydration, weakened immunity, etc.). During the summertime, we’re often reminded by health officials to find a shady spot at noon. Heat and ultraviolet rays are stronger because Earth is closer to the Sun. Beyond the Earth Sphere, the presence of radiation is due to “particles trapped in the Earth’s magnetic field; particles shot into space during solar flares (solar particle events); and galactic cosmic rays.” Astronauts have been exposed to space radiation on six-month missions in the past.

2. Colonization needs to figure out how to deal with toxic/inhospitable atmospheres, so you’re going to need to have controlled environments regardless of whether you go on-planet or on moons. It’s a matter of trial and error. Therefore, astronomers can send space probes to explore surfaces and observe their behaviours (environment) to determine the pros and cons. Sustaining life beyond Earth poses a challenge; in the case of some aforementioned planets and moons, the best bet is to set up colonies within the orbit of the places that are deemed safe. Additional training/workshops for persons interested in relocating to space, and inventions designed to promote safety and longevity must be considered.

3. Colonization needs to figure out how to deal with fluctuating temperatures. The close proximity of the inner planets’ orbits to the sun and the immense distance from the outer planets’ orbits mean regulating temperatures to support human life is going to be a challenge regardless of where you end up. HOW you deal with those depends on the location (e.g. greater shielding for inner planets, use of mirrors and the like for the outer planets).

4. Colonization needs to figure out if it warrants the cost and time of terraforming the two other planets within the Goldilocks Zone (i.e., Venus and Mars) or if it’s better to keep space colonies outside the planets. The good news is Mars’s surface has similarities to Earth’s own. Mars also has a fluctuating atmosphere which depends on its distance from the Sun. Terraforming Mars will be costly, however, because its atmosphere has only small traces of oxygen (good for humans) and nitrogen (great for vegetation and agriculture). The presence of carbon dioxide (which makes up 96% of Mars atmosphere), and carbon monoxide isn’t healthy. Scientists are making plans to ensure that tanks can convert a higher percentage of carbon dioxide into oxygen by 2020. For Venus, terraforming is a possibility, but the presence of sulphuric acid and volcanoes presents a greater challenge for health and safety reasons.

Additional References

Out-Of-This-World Space Colonies as Imagined by NASA in the 1970s and Today. All That’s Interesting. July 17, 2018.

Victor Tangermann, A Timeline for Humanity’s Colonization of Space. Off World via Futurism.

How long would it take to colonise the galaxy? The Open University. November 4, 2011.

Space Settlement. National Space Society. 2018.

Planet Facts. Space Facts. 2019.

Elizabeth Howell. Interesting Facts about the Planets. Universe Today. 2015.

Footnotes

[1]NASA is working on a Mars Mission, with plans to pursue Europa (Jupiter’s moon) within the next decade.

[2]Although currently classified as a “dwarf planet,” this status remains under discussion among experts.

***If anyone wants a free copy of the fanzine Rhythm Generation, you may connect with @acworldbuildingzine. Thanks for reading!***

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earth’s Mightiest Retrospective Ep 50: “Operation Galactic Storm”

(Directed by Boyd Kirkland, Written by Christopher Yost, Original Airdate: October 21, 2012)

“Operation Galactic Storm” begins a two-parter that brings closure to one of Earth’s Mightiest Heroes longest on-going threads, dating back into season one, the Kree Empire and their interest in colonizing Earth. It starts when the Kree intercept SWORD agents investigating nearby the sun due to some strange energy patterns. The Kree warp in and hijack the SWORD vessel while setting a few ships in a pattern near the sun. Abigail Brand shows a message detailing what happened to the SWORD agents to the Avengers. They go interrogate a prisoner who might know what the Kree are after, for Kree Science Captain Mar-Vell.

He tells them why so many alien races have been interested in the Earth throughout the series. Energy around the planet makes establishing stable wormholes for instantaneous space travel easy, while even their most advance ships can take a while to travel across galaxies. The Avengers are warned that the ships near the sun will establish the first portal to help the Kree further expand their empire. It’s also going to damage the sun once it activates. That news rings familiar for the Avengers as they recall the warning Kang gave them in his first appearance that the sun would be damaged in a conflict with the Kree and leave Earth uninhabitable in the future. Mar-Vell says the Kree are likely using that location knowing what will happen as retaliation for the multiple humiliating defeats Earth’s Mightiest Heroes have dealt them in the past. He offers to alter the Quinjet so it can get them to the sun more efficiently by using the same subspace technology the Kree use to space travel and help the Avengers save their planet.

As they’re preparing to leave, they get attack by a Kree stealth-ops team that arrives to keep them from going into space. After some fighting and struggling to see the alien stealth-operatives, Yellowjacket decides to stay behind to keep them busy as the rest of the team and Mar-Vell go to the sun. When they get there and decide to engage the Kree out in space, we get to see the return of the Avengers red and white space uniforms with new ones for Ms. Marvel and Black Panther. The team splits up between rescuing the SWORD agents on their damaged ship and hijacking the other Kree warship to stop the aliens from activating their portal to destroy the sun.

The SWORD ship only has two beings on board, one is SWORD agent Peter Corbeau, who helped the rest of his squad evacuate before the Kree attacked, and the other is a Kree Sentry robot. Meanwhile, the Avengers fighting in space struggle to break through the warship’s force field. They throw everything they have at it, but even Vision can’t phase through it. Mar-Vell and Iron Man figure out they can bust a hole in the shields if they can match its frequency and accomplish it. When they take control of the bridge of the ship, the commanding Kree officer on board tells them they’re already too late to stop the portal from opening. The Avengers realize they’ll need to go inside the portal to destroy its source and keep it from damaging the sun and life on Earth with it.

It’s a move that will require sacrifice from all parties involved. Black Panther needs to stay on the Kree ship to direct the Quinjet through the portal while the rest of the team, Mar-Vell, and Corbeau go inside to destroy the machines projecting it, which will leave them stuck on the other side of the galaxy in hostile Kree territory. Captain America almost refuses to let Black Panther sacrifice himself, but the others remind him of Kang’s warnings. The only way to save the sun and keep that future from coming to pass is to let the fellow Avenger die as he thanks the team for letting him fight by their side. It’s a well-done speech and the sacrifice is given appropriate weight before the Avengers go through the portal and finish their part of the mission. The episode closes on the heroes knowing they were able to save the world again, but unable to enjoy it before realizing they’ve ended up directly in front of a Kree armada.

While all the space action was going on, Yellowjacket and Abigail Brand defended Hydro-Base from the Kree stealth-ops. The Kree’s attack on the facility has several phases, including reuniting Ronan the Accuser with his weapon before freeing him and setting a bomb that will blow up the facility and half of New York with it. This part of the episode serves as another showcase for Hank Pym’s impulsive attitude that’s come along with the Yellowjacket identity and costume. Before he can prevent the Kree from freeing Ronan, Brand calls on him to deal with the bomb the aliens planted on the base and the Kree teleport away with Ronan (Spoilers: this thread goes nowhere next episode and gets left hanging due to the series cancellation.) Yellowjacket gets a fantastic moment where he admits he doesn’t know how to stop the Kree’s bomb from counting down. Brand yells at him for his uselessness before he blasts the device with his shrink ray, reducing it in size until it can’t hurt anything aside from a few molecules. Abigail punches him for good measure for putting her under the stress of thinking they were about to let half a city get blown up.

This episode makes a good first half for the conclusion of the drama with Kree this season. Mar-Vell begins his path towards redemption for selling out the Earth to his people back in “Welcome to the Kree Empire.” The logic behind the necessity of T’Challa’s sacrifice is a little loose and kind of underwhelming considering the direness of Kang’s warnings about what would cause the sun to be damaged, but the vocal performances and visuals sell the moment despite that. Now we’re running down the clock on Avengers: Earth’s Mightiest Heroes with only two episodes left.

Next time, the Avengers meet the mind behind the Kree Empire.

If you like what you’ve read here, please like/reblog or share elsewhere online, follow me on Twitter (@WC_WIT), and consider throwing some support my way at either Ko-Fi.com or Patreon.com at the extension “/witswriting”

#Avengers#Avengers: Earth's Mightiest Heroes#Earth's Mightiest Retrospective#Wit's Writing#TV Review#Marvel Comics#Marvel#superhero tv#superhero animation#animation#comics

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

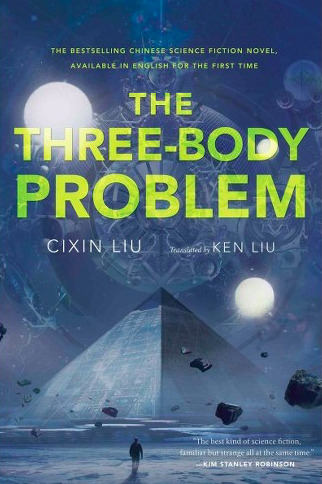

The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu, trans. Ken Liu

An invigorating and gripping book. Probably the best science fiction I have ever read & Cixin Liu is arguably the best sci fi writer alive — in both the “science fiction” and “writer” senses of that term.

The Three-Body Problem asks: If an alien civilization, desperate for survival, invaded Earth — could humanity survive? And would we deserve to? It begins during China’s cultural revolution in 1967, with a brutal act that will shape the future of the whole human race. You might say that this entire book, though packed with plot and information, is merely setting the stage for what’s to come in the next book. A physics professor named Ye Zhetai is being publicly berated in front of a crowd by several passionate young Red Guards, who want him to renounce Einstein’s theory of relativity and thus the “black banner of capitalism” it represents. When he refuses, they attack, whipping him to death with the copper buckles of their belts. The professor’s daughter, Ye Wenjie, has a front row seat to her father’s death. As the crowd disperses, she stares at his body, and “the thoughts she could not voice dissolved into her blood, where they would stay with her for the rest of her life.” These thoughts will haunt her throughout a stint in the Inner Mongolia Production and Construction Corps, cutting down trees in the once pristine and abundant wilderness — so full of life you could reach into a stream at random and pull out a fish for dinner, now transforming into a barren desert in front of her eyes — and at her hands. There, she meets a journalist who questions the wanton deforestation that has also touched her heart. “I don’t know if the Corps is engaged in construction or destruction,” he says. His thinking is inspired by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a copy of which he gives Ye Wenjie to read and which changes her life. It inspires her to wonder: if the use of pesticides, which she took for granted as a “normal, proper—or at least neutral—act,” is destructive to the world, then “how many other acts of humankind that had seemed normal or even righteous were, in reality, evil?”

Is it possible that the relationship between humanity and evil is similar to the relationship between the ocean and an iceberg floating on its surface? Both the ocean and the iceberg are made of the same material. That the iceberg seems separate is only because it is in a different form. In reality, it is but a part of the vast ocean.... / It was impossible to expect a moral awakening from humankind itself, just like it was impossible to expect humans to lift off the earth by pulling up on their own hair. To achieve moral awakening required a force outside the human race.

This idea shapes the rest of Ye Wenjie’s life. It is what prompts her to invite an alien civilization to our world, serving humanity up to them on a silver platter. She helps the reporter transcribe a letter to his higher-ups, warning them of the “severe ecological consequences” of the Construction Corps’ work. This letter is received as reactionary, and the terrified reporter claims Ye Wenjie wrote it, throwing her under the bus. All is not lost for her, however. Because of an academic paper she wrote before the revolution, "The Possible Existence of Phase Boundaries Within the Solar Radiation Zone and Their Reflective Characteristics,” she is not imprisoned, but scooped up to work on a top-secret military research project: an attempt to contact extraterrestrial life. Because it’s so highly classified, it requires a lifelong commitment, one she gladly makes: all she wants is to be secluded from the brutal world. And at Red Coast Base, on an isolated peak deep in the mountains, crowned by an enormous antenna, she finds the solitude she seeks, immersing herself in her work. It is here that, almost by accident, she harnesses the power of the sun to send a message far out into space — a message that, many years later, receives a chilling reply: “Do not answer! Do not answer!! Do not answer!!” This message is from one pacifist member of an powerful alien civilization, far more advanced than our own, who are facing extinction in their own solar system and desperately need to find a new home. The messenger explains that, if Ye Wenjie replies, she will allow this civilization to pinpoint earth’s location, then colonize earth.

Without hesitation, Ye Wenjie replies.

This story unfolds over the course of the book, interwoven with the present day, during which an ordinary scientist named Xiao Wang is experiencing the results of Ye Wenjie’s message. All over the world, scientists are killing themselves — and strange things are happening to him that are shaking his trust in reality and driving him to the brink of suicidal madness. Before it’s too late, he finds out that he is just one target in an intergalactic war. Through a video game called Three Body, he learns about the enemy: the aliens Ye Wenjie contacted all those years ago. These beings live on a planet called Trisolaris, over four light years away from our Earth. Trisolaris has not one, not two, but three suns, which interact in a chaotic, unpredictable, and deadly dance that alternately scorches and freezes the planet, obliterating Trisolaran civilization — over and over again. When the planet is orbiting one single sun, that’s a Stable Era: a time of predictability and peace. But when one of the other suns dances closer, drawing the planet away, the planet then “wander[s] unstably” though the gravitational fields of the three suns, causing chaos: thus, this is known as a Chaotic Era. No one knows when a Stable Era will occur, how long it will last, or what horrors each new Chaotic Era will bring with it. This brutal, unpredictable environment has shaped the Trisolarans physically, psychologically, technologically... everything. As one Trisolaran puts it, the freedom and dignity of the individual is totally suborned to the survival of civilization. It is a totalitarian society, mired in “spiritual monotony.” As one Trisolaran you might call a dissident puts it: “Anything that can lead to spiritual weakness is declared evil. We have no literature, no art, no pursuit of beauty and enjoyment. We cannot even speak of love ... [I]s there any meaning to such a life?”

Trisolaran society, meaningful or not, is teetering on the precipice of doom. The Trisolarans can dehydrate and rehydrate their bodies, turning them into empty husks that can survive the uninhabitable Chaotic Eras — thus, through both perseverance and blind luck, they have endured up to this point. However, they have never been able to solve the “three-body problem” — they cannot predict the three suns’ movement and thus stay one step ahead. (I’m pretty sure the problem is fundamentally unsolvable.) And there’s an even bigger problem on the horizon... literally. Soon, their planet will fall into one of the suns. Trisolaran astronomers discover that their solar system once held twelve planets — the other eleven have all been consumed by the three hungry suns. “Our world is nothing more than the sole survivor of a Great Hunt.” The Trisolarans have little time left and no hope of survival — unless they can find another planet that supports life. That’s when they receive Ye Wenjie’s message. To them, Earth is the Garden of Eden — stable, prosperous, overflowing with life... like the pristine Chinese wilderness before the Construction/Destruction Corps arrived. The Trisolarans build a fleet and set off for Earth. ETA: 400 years. And they do one more crucial thing: they construct and send what they call sophons to earth, or particles endowed with artificial intelligence that can transmit information back to Trisolaris instantaneously and interfere with human physics research to the point of stopping it completely, essentially freezing scientific progress. They are preparing the ground for their arrival. Through the sophons, the Trisolarans see all — the only depths they cannot penetrate are those of the solitary human mind. And did I mention that Trisolarans communicate their thoughts to each other instantaneously, and there is no such thing as deception? Humanity’s edge is our ability to lie and deceive — an edge that the sophons all but obliterate. All our plans are laid bare to them. And so the intergalactic chess game goes on.

All this, essentially... there is so much of it and it isn’t even the plot of the book; it’s just setup, it’s just the premise, it’s just the question Cixin Liu is asking. If such a thing happened, what would humanity do? What unfolds thereafter is his answer. When humanity finds out that the Trisolaran Fleet is on its way, this knowledge is enough to alter our fate forever. An organization called the Earth-Trisolaris Organization, or ETO, arises, with Ye Wenjie as its guru — an organization that seeks to further the Trisolarans’ aims on earth. Battling the ETO: the governments of the earth, desperate to find a way of defeating the Trisolarans and saving the human race. One faction within the ETO, the Adventists, hopes that the Trisolarans will kill us all; humanity, to them, is not worth saving. Another, the Redemptionists, worship the Trisolarans as gods and hopes that they can coexist with errant humanity and, through their influence, elevate — redeem — them. Ye Wenjie is a Redemptionist, and this is essentially her message: “Come here! I will help you conquer this world. Our civilization is no longer capable of solving its own problems. We need your force to intervene.”