#v iii o'keeffe

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Pater being like the baby/lil bro of the group, on account Hawkins calls him "son" as a term of endearment and he also mentions O'Keeffe helped him out.

But Pater is also like "if one of you dies, I get a promotion!"

#v.viii pater#v.v hawkins#v.iii o'keeffe#armored core 6#armored core vi#v viii pater#v v hawkins#v iii o'keeffe

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

eventually want to translate these few quotes from my silent war into a talk between o'keeffe and rusty regarding squad III vs II, with SIS and MI5 being analogous to the two respectively. because i like o'keeffe having to share with snail, just a little bit. he can't have it too easy working at arquebus.

SIS alone receives secret funds, for which it is not accountable in detail, so that it may get information from foreign countries which is not obtainable by ordinary, lawful means. Section V, to which I found myself attached, was in a peculiar position, in more than one respect. To sum up very briefly the place of Section V in the intelligence world: as part of SIS, it was responsible for the collection of counterespionage information from foreign countries by illegal means. The department chiefly interested in its intelligence was MI5, which was responsible for the security of British territory and therefore required as much advance news as possible of foreign attempts to penetrate British secrets. If MI5 makes a mistake, questions are asked in Parliament, the press launches campaigns, and all manner of public consequences ensue, of a kind distasteful to a shy and furtive organization. No such inhibitions hamper the operations of SIS in breach of the laws of foreign countries. The only sufferer is the Foreign Service which has to explain away mistakes to foreign governments, usually by simple denials.

i know pater states o'keeffe is the sole arbiter and chief of intelligence within arquebus and the vespers, but i like the idea that snail and therefore squad II tends to rewrite its job description in order to suit his means. personally, for petty reasons, he's pissed there's a black budget that's not his. professionally, he doesn't trust anyone who isn't him, so of course o'keeffe needs to be watched, and squad III with him.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 3 Acts, 9 Blocks, 27 Chapters Method by Kat O'Keeffe (Aug 16, 2022)

The 3 Acts, 9 Blocks, 27 Chapters Method is supposed to make your plotting easy.

-------

Breakdown of The 3 Acts, 9 Blocks, 27 Chapters Method:

This method was made popular by Kat O’Keefe, so when I found it on youtube I have decided to share it with you, guys.

HERE AR SOME VIDEOS FROM YOUTUBE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fe3eodLF_Uo - HOW TO OUTLINE | 3 act 9 block 27 chapter example

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=94F-3Z6CJJw - How I Outline! [3 Acts: 9 Blocks: 27 Chapters]

-------

First of all, the story is broken into 3 acts. It is then further broken down into 9 chapters per act. Here’s an overview of those acts and chapters.

Chapter Overview:

ACT I

Intro

Inciting Incident

Immediate Reaction

Reaction

Action

Consequence

Pressure

Pinch

Push

ACT II

New World

Fun & Games

Old Contrast

Build Up

Midpoint

Reversal

Consequence

Trials

Dedication

ACT III

Calm Before The Storm

Pinch

Darkest Point

Power Within

Action

Converge

Battle

Climax

Resolution

-------

Chapter Descriptions:

Below is a description of what should happen in each chapter, with examples from a story from start to finish.

ACT I

Intro: Introduce Hero and the ordinary world. Example: We meet Jane and Sarah, two sisters that hate each other. Jane is an overachiever and Sarah is a slacker.

Inciting Incident: A problem disrupts the Hero’s life that will kick off the rest of the story. Example: Jane dies

Immediate Reaction: The Hero deals with the inciting incident and/or the changes that result from the inciting incident. Example: After Jane dies, Sarah’s tattoo starts hurting and she sees visions of Jane. It seems Jane’s ghost is bound to Sarah’s tattoo.

Reaction: Long-term reaction. The reader begins to understand just how the inciting incident will affect the Hero’s life. Example: Sarah freaks out. She doesn’t want to be haunted by Jane. She tries to find ways to exorcise her sister, but nothing works (refusal to the call to action). The sisters determine that Sarah needs to help Jane pass on by dealing with her unfinished business.

Action: The Hero decides to act and makes a decision that will impact the rest of the story. Example: Sarah decides she must get herself into the elite program her sister was involved in.

Consequence: The result of the decision made (see Action). Example: Because of her decision. Sarah now has to study and prepare for the tests.

Pressure: The Hero begins to feel the pressure of the task before them and is stressed. Example: Sarah is taking the test and doing the interview, a high pressure, stressful situation.

Pinch: Things get a little more complicated and the Hero wonders if the right decision was made. (see Action) A plot twist happens. Example: Turns out the test isn’t just a written test. There’s a hands-on portion that Sarah didn’t account for. Jane the ghost sister helps out at the last minute.

Push: The Hero is pushed in a new direction. Example: Sarah gets a tour of the lab. Meets new people that work there. She’s pushed into a new world.

ACT II

New World: The Hero experiences a new world or situation. Example: Sarah’s first day or a few days in the lab. Learning things, spending time with new people, etc.

Fun Games: The Hero explores and interacts in the new world. This is a good place to build relationships, romantic or otherwise, and develop your character more. Example: Sarah starts off a possible romance with someone in the lab who Jane, the ghost sister, hates.

Old Contrast: The Hero compares the new world to the old, and is reminded of how much has changed. Example: Sarah and Jane are fighting. Jane wants Sarah to focus on the work and not the guy she’s just met.

Build Up: This is where you prepare for the major turning point in your story. There is some form of struggle, internal or external, that will motivate your Hero to take matters into their own hands. Example: Sarah and Jane’s fighting gets to a boiling point and Jane decides to leave and not talk to her.

Midpoint: The Hero encounters something that complicates their plans and motivates them to change the course of events. Example: Sarah starts trying to figure out things on her own and then stumbles upon the fact that Jane might have been murdered.

Reversal: Everything changes. Example: The sisters make amends and discuss the possibility of murder.

Consequence: The Hero reflects upon what has happened. Example: Sarah decides to go to the police and try to report the murder. They don’t buy it, they need proof and evidence.

Trials: The Hero takes matters into their own hands and solves or works around the roadblocks that occurred. (See Reversal) Example: Sarah is now wary of everyone in the lab. She starts to investigate everyone in the lab. She might be nervous that she’s the next target.

Dedication: The Hero is now determined to overcome the overall issue. Example: Sarah finds no hard evidence but she’s dedicated to figuring it out.

ACT III

Calm Before The Storm: The Hero finds a solution, but now must overcome doubt, or some other complication. Example: Sarah builds on her romance with the love interest.

Pinch: Plot Twist! Everything is worse than it was. Example: Sarah finds out that the love interest is the murderer.

Darkest Point: Everything seems lost. Example: Sarah is betrayed.

Power Within: The Hero finds the courage and the strength to carry on. Example: Sarah musters up the courage to go on.

Action: The Hero takes action, and overcomes the plot twist, before taking on the overall issue again. Example: Sarah rallies the troops. Talks to the cops and any allies

Converge: Everything comes together: the main plot, the subplot(s), the conflict, etc. The big event is imminent. Example: The sisters have fully fixed their relationship and are working together flawlessly.

Battle: The Hero fights the villain and/or tackles the overall issue, full force. Example: Sarah and Jane fight the nemesis with all they’ve got.

Climax: The Hero either triumphs or succumbs to a fatal flaw. Example: Sarah gets the proof she’s needed and the love interest is arrested.

Resolution: Tie up all loose ends. Make sure the Hero has changed in some way.

Good Luck in writing your book.

0 notes

Text

Georgia O'Keeffe: An American Artist's Life and Legacy | Art History

In this blog post, we will explore the life and art of Georgia O'Keeffe, a prominent American artist known for her unique artistic style and contribution to modern art. We will discuss her famous paintings, poster collections, and quotes that continue to inspire generations.

II. Georgia O'Keeffe's Life and Artistic Style Georgia O'Keeffe was born on November 15, 1887, in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. She grew up in a family of farmers and was raised in rural Wisconsin. O'Keeffe studied art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and later at the Art Students League of New York. She is famous for her artistic style, which combines elements of abstraction and realism. Her paintings often feature close-up views of flowers, landscapes, and natural forms.

III. Famous Georgia O'Keeffe Paintings Georgia O'Keeffe's paintings are highly sought-after and are featured in galleries and museums across the world. Some of her most famous paintings include:

"Black Iris" (1926)

"Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1" (1932)

"Red Poppy" (1927)

"Cow's Skull: Red, White, and Blue" (1931)

"Abstraction White Rose" (1927)

IV. Georgia O'Keeffe Poster and Print Collections Georgia O'Keeffe's artwork is also available in poster and print collections. Some of her most famous prints include:

"The Red Maple at Lake George" (1926)

"Poppies" (1929)

"Calla Lilies on Red" (1928)

"Cow's Skull: Red, White, and Blue" (1931)

"Black and Purple Petunias" (1925)

V. Georgia O'Keeffe Quotes Georgia O'Keeffe's quotes reflect her artistic vision and unique perspective on life. Some of her most famous quotes include:

"I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn't say any other way... things I had no words for."

"To create one's world in any of the arts takes courage."

"I want to be able to paint what I feel. It's easier to paint what you think."

"Nobody sees a flower – really – it is so small it takes time – we haven't time – and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time."

"The days you work are the best days."

VI. Visiting the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum The Georgia O'Keeffe Museum is located in Santa Fe, New Mexico and houses a large collection of her artwork. Visitors can explore her paintings, drawings, and sculpture and learn about her life and artistic vision. The museum also offers educational programs, tours, and events.

If you plan to visit the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, here are a few tips:

Check the museum's hours and admission fees before you go.

Consider taking a guided tour to learn more about the artwork and the artist.

Bring a notebook or sketchbook to take notes or create your own drawings inspired by the artwork.

Take time to explore the surrounding area, as Santa Fe has many galleries and art museums worth visiting.

VII. Conclusion In conclusion, Georgia O'Keeffe's life and art continue to inspire artists, scholars, and admirers around the globe. Her unique artistic style, famous paintings, and poster collections have made her an icon of modern art. Whether you're visiting the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum or exploring her artwork online, take the time to appreciate her contributions to the art world and the beauty she saw in the natural world around her.

Check out our website for buying exhibition posters and Paintings. Merch Fuse.

Top of Form

0 notes

Photo

i. summer days ii. calla lilies iii. flower abstraction iv. from pink shell v. hibiscus vi. the red maple at lake george vii. lake george viii. new york street with moon ix. from the lake x. the barns, lake george

“It's my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.”

Georgia O'Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

#georgia o'keeffe#painting#art#oil painting#female artists#nature#flowers#landscape#mountain#god#new york#abstract#moon

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐌𝑢𝑗𝑒𝑟 𝐼 – 𝘞𝘪𝘭𝘭𝘦𝘮 𝘥𝘦 𝘒𝘰𝘰𝘯𝘪𝘯𝘨 (1950–1952)

Willem pintó una serie de seis obras representadas por mujeres, denominada "Woman".

"Woman I" sería iniciada por De Kooning en 1950 trabajando después frenéticamente y durante dos años sobre esta imagen monstruosa de mujer. Durante esos dos años cambiaría constantemente esta imagen amenazadora, añadiendo capas y capas sucesivas de pintura, raspándolas después para volver a empastar, buscando algo que solo el podría explicar. A principios de 1952, De Kooning abandonó este lienzo sin terminar y comenzó a pintar "Woman II", "Woman III", y "Woman IV", otras tres obras semejantes a "Woman I" y en las que también aparecen esas horribles mujeres con ese aspecto casi diabólico. Se cuenta que el historiador de arte Meyer Schapiro visitó el estudio de De Kooning en la primavera de ese mismo año animando al artista a retomar su "Woman I" lo cual hizo a la vez que terminaba las otras tres. Todavía pintaría a finales de ese año y principios de 1953 las "Woman V" y "Woman VI" siguiendo el mismo estilo de las anteriores.

¿Puedes creer que tardó dos años en hacer "Mujer I", utilizando la técnica de rociar pintura con su pincel y ser bruto con cada pincelada? El tipo pintaba capas y capas, para luego rasgarlas, quitarlas y pintar otras encima, hasta obtener este resultado. A simple vista es chocante y no gusta demasiado, la representación no canónica de una mujer grande, con expresión feroz, músculos formados, una cara poco agradable… los analizadores de esta obra –y sus compañeras– llegaron a hablar de cosas horribles que el pintor quiso retratar, ideas muy retorcidas resguardadas en el famoso psicoanálisis. Sí, a primera ojeada impacta muchísimo, pero como dijo O'Keeffe, la gente seguirá viendo lo que se le venga en gana y nunca lo que el pintor ve al realizar sus obras. Nunca veremos lo mismo que otra persona ve.

Verás, en el arte, las visualizaciones son muy relativas, porque éste lleva, empuja, a que uno vea desde el corazón, la razón y nuestra percepción estética. Nos demanda sentir y empaparnos de recuerdos enterrados, nos incita a sentir y enterrarnos de llenos en los trazos hasta tener una historia concreta en nuestra mente, en nuestro cuarto imaginativo.

Habrán muchas cosas que tú y yo no veremos de la misma forma, cosas que se sientan diferentes y no seamos capaces de pararnos en el mismo lugar que el contrario, pero eso no quita el hecho de que ellas nos harán sentir, nos acercarán desde las emociones y nos incitarán a compartir nuestros pensamientos más cálidos, y también, lo más analíticos. Sólo necesitamos tiempo, paciencia, quitar capas y capas de pintura para seguir retocando encima hasta que estemos satisfechos de nuestro lienzo, hasta que nuestras ideas nos tomen de la mano y nos lleven a un viaje en común cargado de preguntas sin insignificancia, bañado en arte y recompensa ante el esfuerzo puesto para que se vea de la manera en que nuestros ojos lo perciben. Sólo se necesita de la imaginación.

0 notes

Text

La fotografia come forma d’arte (quarta parte)

di Lorenzo Ranzato

I territori del “fotografico”: pittorialismo, documentarismo, concettualismo

Il riconoscimento della fotografia pittorialista come forma d’arte

La rapida carrellata storica che abbiamo compiuto, a partire dalla seconda metà dell’Ottocento sino alla chiusura della rivista Camera Work nel 1917, ci ha consentito di tracciare una panoramica del pittorialismo europeo e statunitense, ma soprattutto di conoscere metodi e stili di alcuni dei suoi più autorevoli rappresentanti, i cosiddetti artisti-fotografi. In questo modo, abbiamo potuto comprendere come il pittorialismo sia stato non solo “un’insieme piuttosto eterogeneo di idee su ciò che rende buona una fotografia d’arte”[i], ma sia diventato anche il primo vasto movimento fotografico internazionale, che si è guadagnato un proprio spazio di autonomia fra le arti maggiori.

A questo successo hanno contribuito senza dubbio le esperienze dei pittorialisti europei, ma un impulso determinante è stato dato dal movimento Photo-Secession (Edward Steichen, Clearence White, Käsebier, Frank Eugene, F. Holland Day e Alvin Langdon Coburn) e soprattutto dal loro più autorevole rappresentante, Alfred Stieglitz. Lo stanno a confermare le iniziative portate avanti dallo stesso Stieglitz, sia con la pubblicazione di Camera Work, sia con le diverse mostre realizzate, fra le quali spicca l’International Exhibition of Pictorial photography tenuta a Buffalo nel 1910, che segna il punto più alto dell’esperienza pittorialista europea e statunitense.

Negli anni successivi alla mostra di Buffalo il movimento Photo-Secession perde coesione, anche a causa dei modi autoritari di Stieglitz e - complice anche l’avvento della Prima Guerra Mondiale - conclude la sua parabola nel 1917, quando Stieglitz scioglie il movimento e chiude la rivista Camera Work.

Purismo fotografico vs. pittorialismo

Il riconoscimento artistico della fotografia pittorialista rappresenta indubbiamente il più grande risultato ottenuto da Stieglitz e dal suo gruppo, ma all’interno di questo variegato movimento internazionale restano ancora molte questioni aperte, che ruotano prevalentemente attorno all’irrisolto rapporto fra pittura e fotografia, che ora bisognerà nuovamente affrontare.

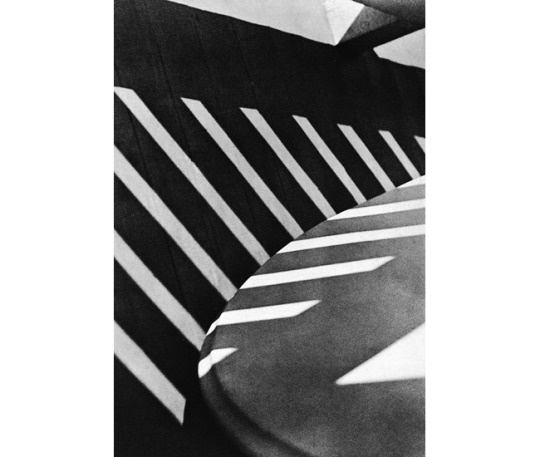

Paul Strand, Astraction-porch shadows, Connecticut, 1916

Dobbiamo fare riferimento ancora alla figura di Stieglitz che, attratto dal nuovo linguaggio fotografico di Paul Strand che incarna i nuovi principi della “fotografia pura”, pubblica le sue fotografie negli ultimi due numeri di Camera Work: nelle opere di Strand vede “una versione fotografica dell’astrazione pittorica” tipica dei dipinti di Picasso e che ora ritrova “nella sua prima passione, la fotografia”[ii]. Non dimentichiamo che sarà lo stesso Stieglitz a ospitare e a far conoscere le nuove tendenze dell’avanguardia artistica europea proprio a New York presso la Galleria 291, con mostre dedicate a Matisse, Cézanne, Picasso, Rodin.

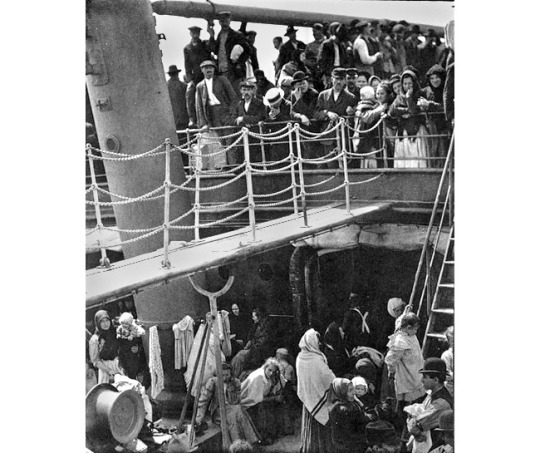

Alfred Stieglitz, The Steerage, Il ponte di terza classe, 1907-1911

Già da queste brevi considerazioni, possiamo intuire come nei primi decenni del Novecento si radicalizzi una nuova contrapposizione fra linguaggi fotografici che - come ci racconta Luigi Marra nel suo libro, più volte citato Fotografia e pittura nel Novecento (e oltre) - sembrano apparentemente diversi: da un lato il purismo della cosiddetta “fotografia diretta” (straight photography), dall’altro il consolidato filone del pittorialismo fotografico, che in diversi modi continua a imitare la pittura impressionista.

Per rappresentare questo cambiamento di linguaggio inaugurato da Strand, si ricorre anche alla fotografia più emblematica di Stieglitz, La terza classe, considerata da molti critici il punto di passaggio “da uno stile pittorico a uno stile documentaristico”[iii]: è un unico scatto realizzato durante la traversata verso l’Europa, con una portatile Auto Graflex nel 1907, ma viene pubblicato su Camera Work solo nel 1911, quando Alfred è del tutto convinto che questa fotografia sia la sua prima opera modernista.

L’equivoco della contrapposizione tra pittorialismo fotografico e straight photography

In realtà, se seguiamo il ragionamento di Marra, il passaggio dal pittorialismo alle fotografia diretta (o purismo fotografico), considerato da molti critici come l’affrancamento della fotografia dalla pittura è una questione mal posta. In effetti, “sotto le apparenze di un rinnovamento linguistico capace di far emergere la tanto invocata specificità fotografica” sembrano emergere ancora forme di “un pittoricismo ben più potente e subdolo”[iv].

Ma dove sta l’equivoco?

Marra sostiene che ci troviamo di fronte a un evidente “errore metodologico”: “si è attribuita una categoria generale (il pittorialismo, cioè l’essere simile alla pittura) a una particolare interpretazione della pittura, l’Impressionismo appunto”, nella convinzione che la fotografia pittorialista sia stata un fenomeno circoscritto soltanto ai due o tre decenni a cavallo tra Ottocento e Novecento. Questo “limite temporale ma soprattutto stilistico indurrebbe a credere che “la fotografia possa essere definita pittorica solo quando imita l’Impressionismo e non altre scuole” [v].

Seguendo l’interpretazione critica di David Bate, che abbiamo già brevemente illustrato nella prima puntata, appare del tutto evidente che il pittorialismo, assieme al documentarismo e al concettualismo, siano le tre categorie del fotografico[vi] “entro le quali racchiudere i comportamenti della fotografia nel tempo e fino alla contemporaneità”[vii], comportamenti che assumeranno di volta in volta una propria specificità linguistica e poetica.

Ne consegue che “il pittorialismo fotografico non è un fenomeno limitabile a un determinato periodo storico e a una particolare scuola”, ma si ripresenta ogni volta che “la fotografia segue la logica complessiva della pittura”[viii].

Possiamo dunque riconoscere nel linguaggio della straight photography nuove forme di pittorialismo fotografico, che ovviamente si distinguono dalle più tradizionali soluzioni proposte dal “pittorialismo storico”, ispirato dall’accademismo e basato sui metodi di manipolazione dell’immagine (due nomi per tutti: l’inglese Robinson e il francese Demachy).

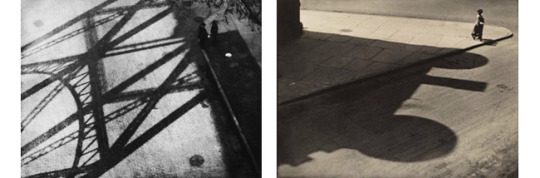

Paul Strand, Vedute di New York, 1915 e 1916

Sotto questo profilo, esemplare è l’opera di Paul Strand che, alla ricerca di un’autonomia della fotografia, rifiuta il linguaggio del pittorialismo storico e disprezza i cosiddetti “fotopittori”. Ma in questo modo ricade in una nuova forma di “pittorialismo forse inconsapevole ma potentissimo”[ix] che riprende le modalità stilistiche delle avanguardie e risente delle influenze del cubismo e dell’astrattismo. Quando afferma che lo specifico fotografico va identificato con “le forme degli oggetti, le tonalità di colore relative, le strutture e le linee”, in realtà sta descrivendo quello che costituisce “lo specifico trasversale di tutta la pittura”[x], peraltro ancora rintracciabile in molta fotografia contemporanea.

Tutto ciò vale anche per la fotografia di altri autori come ad esempio Clarence White, Coburn e Stieglitz, quando il loro linguaggio fotografico si allontana dal “gusto” impressionista e si avvicina a quello delle nuove correnti artistiche del primo Novecento.

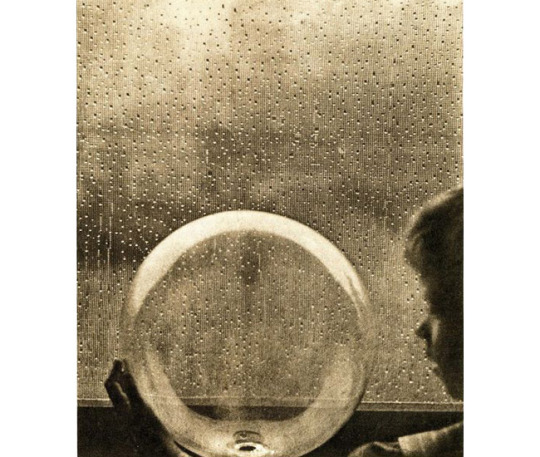

Clarence White, Drop of rain, 1908

Possiamo dunque concludere con Marra che con l’avvento della straight photography il filone pittorialista non si esaurisce, ma piuttosto si aggiorna, con “un passaggio di tutela dall’area impressionista a quella “neoplastica-costruttivista”[xi].

Alvin Langdon Coburn, Vortografia, 1917

Peraltro, il concetto di neopittorialismo introdotto da Marra e anche da Bate, con sfumature diverse, per definire questi nuovi orientamenti fotografici, può diventare un’utile chiave interpretativa, per affinare il nostro “occhio critico”, ogni volta che andremo a indagare tipi di fotografia che in qualche modo fanno uso di linguaggi riconducibili a qualche tendenza pittorica, sia essa figurativa o astratta. Ciò vale ad esempio, per la fotografia astratta di Làslò Moholy-Nagy o per le composizioni alla maniera di Malevič o Modrian della newyorkese Florence Henri – commentate da Marra -, oppure in epoca più vicina a noi, per i tableaux del canadese Jeff Wall – che David Bate accosta a quelli ottocenteschi di Robinson – o infine per le grandi composizioni di David La Chappelle, dalla quali emerge prorompente lo scontro “tra artificio e natura”.

Alfred Stieglitz, Fofografie di Georgia O'Keeffe, 1917-1918

Oltre il pittoricismo: “l’arte del documento” e la fotografia concettuale

Per ricercare l’autonomia della fotografia dalla pittura dovremo esplorare altri territori del “fotografico”, dove si consumerà lo scontro dialettico tra pittoricità ed extrapittoricità[xii]. E le prime avvisaglie di un autentico sforzo antipittorialista potremmo rintracciarle in quel tipo di fotografia che “entra in relazione con le ricerche extrapittoriche sviluppate in area dadaista-surrealista”[xiii].

Ad ogni modo, come afferma Walter Benjamin, a incarnare la nuova forma d’arte dell’epoca moderna è il documento fotografico[xiv], che trova negli album fotografici della Parigi di Eugéne Atget l’esempio storico più significativo. Rilevanti esponenti della fotografia documentaristica saranno i fotografi della Farm Security Administration in America e August Sander ed Henri Cartier-Bresson in Europa, solo per fare alcuni nomi.

L’affrancamento definitivo dalla cultura del pittoricismo avverrà soltanto con l’affermazione della fotografia concettuale[xv], che nascerà sulla scia delle esperienze artistiche del concettualismo: performance, body art, land art, narrative art… Solo allora la fotografia potrà acquisire in modo completo quella specifica identità extrapittorica, che, come sappiamo, trova origine nella poetica del dadaismo e nella teoria del ready-made di Marcel Duchamp[xvi]. A titolo esemplificativo, seguendo le indicazioni di David Bate sul tema dell’assenza della presenza, possiamo ricordare Richard Long e Victor Burgin, o la sequenza Autoseppellimento di Keith Arnatt (1969); oppure, seguendo il racconto di Claudio Marra, l’opera di Francesca Woodman sul tema del corpo, o le opere narrative di Franco Vaccari e Duane Michals “maestro della narrazione pseudotriller di gusto cinematografico”, o ancora i lavori di Cindy Sherman, in bilico tra finzione e realtà, per arrivare alla fotografia italiana del “pensiero debole”, rappresentata da Luigi Ghirri, Gabriele Basilico, Mimmo Jodice e Guido Guidi.

Da questo punto in avanti, grazie anche ai nuovi scenari aperti dalla moda e dalla pubblicità - con la contaminazione fra ricerca artistica e industria culturale -, per il medium fotografico si schiudono nuovi orizzonti, che lo portano ad acquisire progressivamente una rilevante centralità in tutti i processi di produzione artistica contemporanea, sia nelle arti dello “spazio” (pittura, scultura, installazioni), sia nelle arti del “tempo” (video, media digitali e performance)”[xvii].

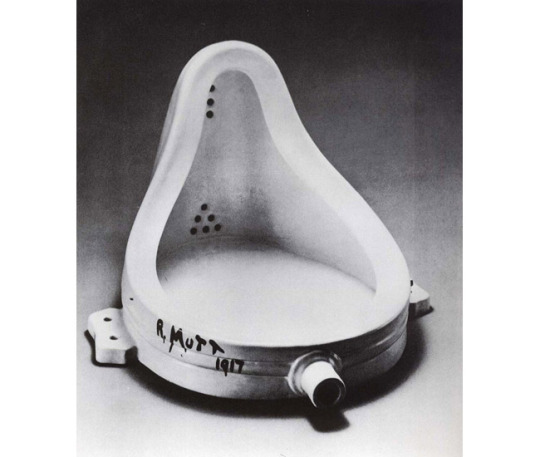

Fontana di Marcel Duchamp, fotografata da Alfred Stieglitz, 1917[xviii]

Dunque, non ci resta che concludere condividendo la tesi di David Bate: riconoscere che è tramontato il tempo della fotografia come arte e pensare piuttosto di essere entrati nella nuova epoca dell’arte come fotografia.

[i] David Bate, La fotografia d’arte, Einaudi, 2018, p.45.

[ii] Alfred Stieglitz, Camera Work-The Complete Photographs 1903-1917, Tachen, 2018, p.213.

[iii] Juliet Hacking (a cura di), Fotografia la storia completa, Atlante, 2013, p.183.

[iv] Claudio Marra, Fotografia e pittura nel Novecento (e oltre), Mondadori, 2012, p.120.

[v] Ivi, p.121.

[vi] David Bate, op. cit. p.9.

[vii] Roberta Valtorta, “Dissimiglianza vs. somiglianza: un concetto in flashback”, in rivista di studi di fotografia rfs, n.8, 2018.

[viii] Claudio Marra, op. cit. p.121.

[ix] Ivi, p.125.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ivi, p.131.

[xii] Ivi, p.120 e 122.

[xiii] Ivi, p.131.

[xiv] David Bate, op. cit. p.102. Per una conoscenza più approfondita del documento come forma d’arte, si consiglia la lettura di parte del cap. 3 “L’arte del documento”: pp. 83-112.

[xv] Si veda al proposito la parte iniziale del cap. 4 “Il concettualismo e la fotografia d’arte”, in David Bate, op.cit., e in particolare le pagine dedicate al ready-made Fontana, di Duchamp: pp140-143.

[xvi] Con il ready-made Duchamp attua una rivoluzione epocale, negando l’arte come attività manuale. In altri termini, l’artista non è più tale per l’abilità di manipolare la materia, ma per la capacità di creare nuovi significati.

[xvii] David Bate, op.cit. p.3.

[xviii] Anche in questo caso torniamo a incrociare l’onnipresente Alfred Stieglitz, quando nel 1917 Duchamp scandalizza l’ambiente artistico di New York, proponendo il ready-made Fontana, costituito da un orinale bianco firmato con lo pseudonimo “R. Matt”, che viene rifiutato alla mostra della Società degli artisti indipendenti, ma trova spazio in un’altra mostra organizzata dallo stesso Stieglitz che fotografa l’opera e l’importante riproduzione viene pubblicata sempre nel 1917 sul giornale dadaista The Blind Man. Fontana può essere considerata “un prototipo concettualista” (Bate, op. cit. p.141) ed è l’opera d’arte più dissacrante e influente del XX secolo: la geniale operazione dadaista, che postula il rifiuto dell’arte tradizionalmente intesa, consiste nell’estrapolare dal contesto un oggetto comune - in questo caso l’orinatoio -, che grazie a questa selezione eseguita dall’artista, diventa esso stesso opera d’arte.

0 notes