#unschematically

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

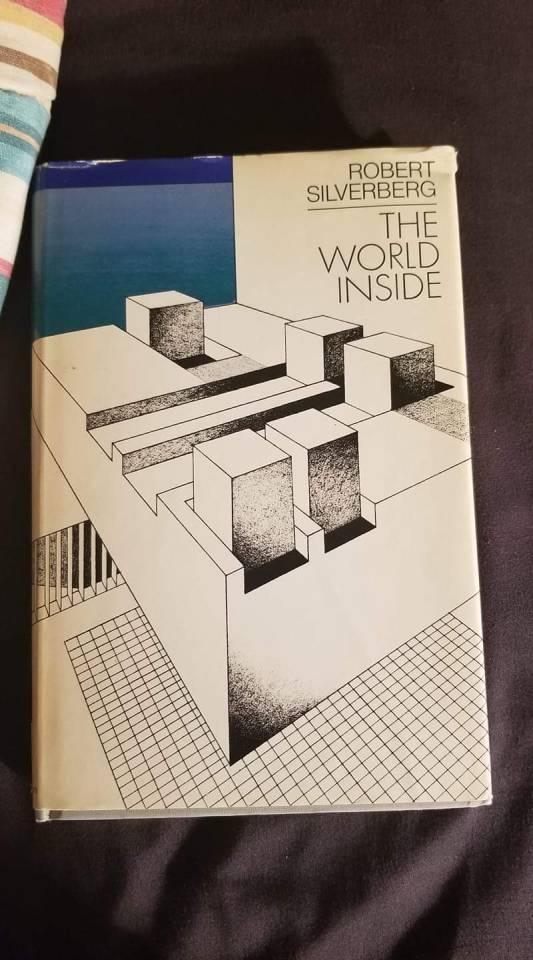

The World Inside

By Robert Silverberg

This story is much unlike any I have read previously. A couple of centuries in the future the vast majority of humans have isolated themselves within buildings three kilometres high, remaining in their own building for their entire life, with extremely rare exceptions. Those outside the urban monads, as they are called, work the fields to supply food for the larger population. It is also indicated that in this time they are a space-faring species having adapted Venus to support colonies of humans, although the details of said colonies are sparse.

Presented are many cultural norms that are different from those which we currently encounter, especially regarding sexuality and privacy. In this literary explorarion sexual openness is expected of all members of the community upon maturation. In the enclosed society everything, from sleeping, to sexual activities, to toilet breaks, is done in the open and without restraint. Although human interaction and openness is encouraged, there are some oppressive measures within this society that cause stress on some members, especially those whom become curious about the world outside and wish to fulfil their wanderlust.

Although the situation and culture are vastly different from that within which we live, and even more different from that of the time of its publication in 1971, the characters show a depth which intimately connects the reader with their experience.

Even the characters in the novel discuss the evolution and adaptations humans would have required to have occur to accept and thrive within such a community, so vastly different of that of a few generations prior.

This book has drawn me in from the first page, being immersed into a collection of lives, struggles, perseverance, wonder, and self-reconciliation. It is not for those readers whom are disturbed by some sexual and dark imagery, but it is a great story for those who are intrigued about one of many possibly futures our species may create.

A few favourite quotations from the novel:

'In the morning, at his office, he begins his newest line of inquiry, summoning up the data on the sexual mores of ancient times. As usual, he concentrates on the twentieth century, which he regards as the climax of the ancient era, and therefore most significant, revealing as it does the entire cluster of attitudes and responses that had accumulated in the pre-urbmon industrial era. The twenty-first century is less useful for his purposes, being, like all transitional periods, essentially chaotic and unschematic, and the twenty-second century brings him into modern times with the beginning of the urbmon age. So the twentieth is his favorite area of study. Seeds of the collapse, portents of doom running through it like bad-trip threads in a psychedelic tapestry.' ~narrator, regarding Jason Quevedo, p. 78.

'He tries to keep this silly sense of embarassment a secret. He knows that it doesn't fit with the image of himself that everyone else sees.'

...

'If they only knew. Underneath it all was a vulnerable boy. Underneath it a shy, insecure Siegmund. Worried that he's climbing too fast. Apologizing to himself for his success. Siegmund the humble. Siegmund the uncertain.'

~narrator, regarding Siegmund Kluver, p. 95.

"Very often, we project onto other people our own secret, repressed attitudes. If 'we' think, deep down, that something is trivial or worthless, we indignantly accuse other people of thinking so. If we wonder privately if we're as conscientious and devoted to duty as we say we are, we complain that others are slackers."

~Rhea Freehouse, p. 103.

"You absolutely don't understand. Should we turn our commune into and urbmon? You have your way of life; we have ours. Ours requires us to be few in number and live in the midst of fertile fields. Why should we become like you? We pride ourselves on 'not' being like you. So if we expand, we must expand horizontally, right? Which would in time cover the surface of the world with a dead crust of paved streets and roads, as in the former days. No. We are beyond such things. We impose limits on ourselves, and live in the proper rhythm of our way, and we are happy. And so it shall be forever with us." ~Artha, p. 143.

"It's all here, isn't it? The story of the collapse of civilization. And how we rebuilt it again. Vertical as the central philosophical thrust of human congruence patterns." ~Siegmund speaking to Jason, p. 180.

0 notes

Text

Omertà and the Prisoner’s Dilemma

One of the most discussed thought experiments in game theory -- probably the most discussed topic in game theory -- is the prisoner’s dilemma. Here is a description of the prisoner’s dilemma from Wikipedia:

Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of communicating with the other. The prosecutors lack sufficient evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge, but they have enough to convict both on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the prosecutors offer each prisoner a bargain. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to: betray the other by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the other by remaining silent. The offer is:

If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves 2 years in prison

If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve 3 years in prison (and vice versa)

If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve 1 year in prison (on the lesser charge).

I have to wonder if those who formulated the prisoner’s dilemma, and the millions who have subsequently discussed it, had even a passing familiarity with criminal gangs or their culture. Cross culturally and over time, criminal subcultures abide by a “code of silence,” the most famous of which is the tradition of Omertà among Italian organized crime syndicates. (For readers who have watched Breaking Bad, you will immediately recognize this behavior in the character of Hector Salamanca, who is shown to be fully aware of his circumstances, despite his disabilities, but also completely unwilling to cooperate with the police, even when it might seem superficially to be in his interest to do so.)

Given that silence and non-cooperation with legal authorities is not merely the default position of criminal gangs, but has been brutally enforced through retaliation not only against “snitches” but also against their families, if, as in the prisoner’s dilemma, members of a criminal gang are held and questioned separately, they know all too well that they are expected -- and this expectation is contextualized in a long history -- to remain silent, even if silence means death or a long sentence of incarceration.

How anyone would even bother to discuss the prisoner’s dilemma without an examination of the cultural expectations of a code of silence strikes me as ludicrous, but it also points to something important. Science derives much of its predictive power, hence its power as a pragmatic force to extend human agency, from its careful and creative use of scientific abstraction. However, while a great deal has been written about scientific method, almost nothing has been written about scientific abstraction.

For science to be successful, the scientific method must operate within the parameters of just the right degree of abstraction -- neither too little nor too much. Too little abstraction leads to Pyrrhonian skepticism, as the parsing of empirical details will always lead to a uniqueness that defies schematization and prediction. Too much abstraction leads to circumstances such as the failure of the prisoner’s dilemma to describe actual human behavior: we have abstracted from too much of the context, something has been lost, and the theory that grows out of the his impoverished context is misleading.

The problem is that science itself is silent on arriving at what exactly constitutes just the right degree of abstraction. This is another way in which theory development in science is unscientific. The greatest scientists who make the greatest discoveries are those who possess an uncanny knack for hitting on just the right degree of scientific abstraction within a body of knowledge heretofore unschematized by science. There is no way to teach having a “knack,” and there is no method that can substitute for it.

#game theory#prisoner's dilemma#Hector Salamanca#omertà#code of silence#scientific method#scientific abstraction

0 notes