#to be fair my breakfast is bland and not at all sustainable BUT IT'S STILL ANNOYING

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

totally not projection for testosterone hunger headcanon:

post plaga infection, not only does leon crave the weirdest and most disgusting shit (see: raccoon moment in the dumpster, old and rotten roadkill)

he also has to eat so much to account for his funky lil enhanced state that he very easily gets the shakes because well two bowls of cereal and some pancakes wasn't fuckin enough for his meat mecha and now he's sick and shaking as he gets some proper *protein* a mere two hours later. bullshit.

#resident evil#leon s kennedy#headcanons#i have barely moved beyond straightening up and i feel like i'm full of bees#to be fair my breakfast is bland and not at all sustainable BUT IT'S STILL ANNOYING#fuckin hate having to take care of this meat suit

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 Professional Athletes Share The Workout and Fitness Tips That Got Them to the Top

As a reader of Men's Health, it would seem a fair assumption that you know what's required to stay healthy, both in body and mind. Less known, however, is how the men and women at an elite level keep themselves at the top of their game for years — sometimes decades — on end, surpassing feats that previously weren't thought possible.

Below, we've compiled nine case studies from our annual Body Issue, an edition of Men's Health that celebrates a tapestry of world-beating champions, each with a body that's built for purpose — whether that's running 26.2 miles in under two hours, hoarding gold medals at the Olympics or being crowned The Fittest Man on Earth consecutively for four years. This is what it takes to reach the top.

Eliud Kipchoge The Greatest Marathon Runner of All Time: 35-Years-Old, 170cm, 56kg

In most sports, the issue of who is the GOAT is a matter of endless contention. In the world of long-distance running, however, there is simply no dispute: Eliud Kipchoge is the most extraordinary athlete over a distance of 26.2 miles that the world has ever seen.

In 2012, the remarkable Kenyan finished his first half-marathon in under an hour, the third-fastest debut ever. A year later, he won his first marathon in Hamburg, beating the field by more than two minutes and setting a course record.

For his first major in Berlin, just a few months on, he came second behind former world-record holder Wilson Kipsang. Even then, he still posted the fifth-fastest time in history. Since that relative disappointment, he has won every marathon he’s run on the world stage, including the gold medal at the Rio Olympics. That’s 11 in a row, including Berlin and London four times.

Then, last October in Vienna, Kipchoge set out to achieve the impossible. The sub-two-hour marathon had been mythologised possibly even more than the four-minute mile. He had trained relentlessly, clocking 140 miles per week, combining punishing speed sessions and strength training, all at high altitudes. But it was perhaps Kipchoge’s mental strength that proved decisive in Austria.“Some people believe it is impossible,” he said before the event. “My team and I believe it is possible. We will prove them wrong.” When Kipchoge broke the tape in Vienna, one hour, 59 minutes and 40 seconds after he started, he not only proved his doubters wrong – he turned a collective dream into reality.

"I believe in a calm, simple and low-profile life. You live simply, you train hard"

“It’s not just the speed at which he runs and the incredible endurance that sustains him,” says Rick Pearson, senior editor of Runner’s World. “It’s the way he does it. Kipchoge’s running style is a thing of beauty – pure poetry in motion. It’s smooth, it’s serene, there’s no wasted effort. And somehow, he tops it all off with a megawatt smile.”

Indeed, what makes Kipchoge’s achievements all the more astounding is his humility. In between running, he works on the family farm, collecting and chopping vegetables. “In life, the idea is to be happy,” he says. “So, I believe in a calm, simple and low-profile life. You live simply, you train hard, and you live an honest life. Then you are free.”

Peaty harnessed his competitiveness to push himself to new lengths

Tom Watkins

Adam Peaty The Leviathan of the Olympic Pool: 25-Years_old, 191cm, 93kg

By Ted Lane

Hitting the pool is a tranquil way to boost fitness and sink stress – at least, it is for ordinary men. Olympic gold medallist Adam Peaty takes a more combative approach. “I love the aggression of racing,” he says. “You have to be very composed when you’re swimming, but I use that composure in an angry way.” If you’ve been following Peaty on Instagram during the lockdown, you will have seen him repping out parallette press-ups in a weighted vest, wearing all black and sporting a quarantine buzz cut. This militant aesthetic only serves to reinforce the brutality of his workouts.

This focused aggression has yielded exceptional results. As well as becoming the first male British swimmer to win the gold medal in the 100m breaststroke for 24 years at the 2016 Olympics in Rio, Peaty has set 11 swimming world records. He became the first man to break the hallowed 58-second mark in the same event. Then he broke the 57-second mark.

“In the water, all of this comes from your core – it powers every stroke.”

“Adam has got reality distortion,” says coach and 2004 Olympian Mel Marshall. “He doesn’t see limits – he just sees opportunities.” Which comes in handy when Marshall floods his week with a staggering workload, both in the pool and on dry land. Peaty swims a breathtaking 50km each week; 5km in the morning, 5km in the afternoon, Monday to Friday. But it’s far from a mind-numbing slog. “Tuesday afternoon is intense,” says Marshall. “He does 40 25m reps – each one in 60 seconds. That’s 12 seconds of sprinting, 50-ish seconds of recovery, 40 times.”

It may lack a barbell, but it’s an EMOM workout to make you wince. “His other high-intensity session is 20 100m reps: four reps at lactate threshold [30bpm below his maximum heart rate], with one recovery, then three reps at his VO max [10bpm below his maximum heart rate], with two recovery, and repeat.” And that’s just his pool work.

Peaty’s gym sessions dovetail with his water-based workouts. On Mondays, he follows up a kick-based pool session with an upper-body shift pumping iron. There’s a lot of core work, too. “On dry land, you have the ground to offer stability and provide leverage for movement,” says Marshall. “In the water, all of this comes from your core – it powers every stroke.”

By his own admission, Peaty is intensely competitive – fiercely, even. But it’s his ability to absorb the workload that sets him apart. “He recovers incredibly quickly and he adapts incredibly quickly,” says Marshall. Curiously, his coach feels that it’s the foundations laid in the gym early on that are ultimately responsible for his success.

“Starting young means he can take advantage of all of those hormones coursing through his body,” says Marshall. “And those benefits then continue. The man is a workhorse.” Which is bad news for those playing catch-up before the next Olympics.

Joshua reclaimed all he had lost by learning to play to his strengths

David Venni

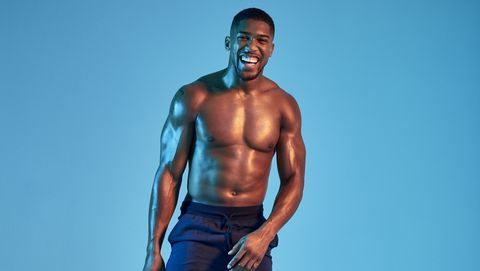

Anthony Joshua Unified Heavyweight Boxing Champion: 30-Years-Old, 198cm, 108kg

By David Morton

Men's Health: Last December, you went into your second fight with Andy Ruiz with a noticeably different game plan to when you lost your titles – WBA, IBF, WBO and IBO – to him earlier in 2019. Was that the key to winning your belts back?

AJ: I think it’s all about adapting. Different circumstances require different preparation. It was the same war, but I had learned a lot from the first battle. Ruiz isn’t the type of fighter that you go head to head with. For the first fight, I was planning on going in there and trading with him. But there’s an old boxing saying: “You don’t hook with a hooker!” So, what did I do? I went in there and hooked with a hooker and the actual hooker came out on top.In the second fight, I went in there and he tried to box with a boxer. And I came out on top. I had to learn what my strengths were and what his weaknesses were, and then I just boxed to those. That’s your basic foundation: never play to someone else’s strengths. In anything you do, everyone has their own strengths. If you play to theirs rather than yours, they are always going to come off better than you in the long run.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

MH: You weighed in almost 5kg lighter for the second fight and were under 108kg for the first time since 2014. How did you adapt your training to come in so visibly leaner?

AJ: Ha, ha! You want me to give away my secrets? You’ve just got to be specific. Training is all about what you’re trying to achieve. To prepare for 12 rounds of boxing, it sounds obvious, but you’ve got to box, box, box. And that’s what we did.

There’s not much point boxing and then spending time in the swimming pool to build endurance, because all you’re doing is building swimming endurance. The same goes for boxing a little bit and then spending hours lifting weights, because that’s for weightlifters. The best boxing stamina work you can do is to hit the heavy bag or shadow box. Everything that involves boxing without getting injured is the best form of training.

It’s a simple thing that’s easy to overlook. If you want to get good at something, do that thing. Focus on it. We try to add this and that, strip it back. But you need to box more if you want to be in shape for boxing.

Joshua found success in stripping back his approach

David Venni

MH: In what way did you change your nutrition? Is it true that Wladimir Klitschko advised you to reduce your salt intake?

AJ: I did cut out salt leading up to that fight. But the food was so bland! You don’t realise how much we depend on salts and sugars. When you remove them, you realise what the true taste of food is like. It had a real benefit, though, because it stripped my body of all the excess sugar and salt I didn’t need, and I managed to lose a shedload of weight.

Chicken and broccoli are tough when you can’t put any spice on them. Someone said to me that it’s not the chicken we like – it’s the spice and the sauces. That’s why I think vegetarians and vegans are onto something. We’re not meant to like chicken. They put the same sauces and spices on vegetables and get that taste and texture.

MH: What’s your diet like coming up to a weigh-in for a fight?

AJ: It’s pretty spot on. Weigh-in is usually about 2pm, so I will have had breakfast and lunch by then. Luckily, I don’t have to “make” weight, so I just continue my preparations like it’s another day. I don’t prepare for the scales; I just use it as an opportunity to showcase my work ethic and how hard I’ve been training.

MH: All boxers come in for criticism on social media. How do you handle negative comments or haters?

AJ: I think that it’s hard to ignore it. I’m not going to lie and say that I don’t pay attention to any of that, because it’s impossible not to see it. I started my social media on my own and, even though it has turned into a business page, I still handle a lot of it myself. I think that it’s fine to have doubters, as long as you don’t believe what they’re saying the whole time. You have to prove your doubters wrong. When they don’t believe, you should always believe.

"You’ve got to be specific: training is all about what you are trying to achieve"

The doubters aren’t always bad, either. You just have to try to find something positive out of it. They might say, “You’re shit, and you’re going to get knocked out because your hands are too low” – and I would think, “That’s a good indication I’ve got to keep my left hand up.” I use the doubters as a positive factor, not as a negative one.

MH: You’ve occasionally been called out for being more of an aesthete than an athlete. What do you think is the most underrated part of a boxer’s physique?

AJ: Their head! That’s where you take the most punishment. Everyone says it’s all about a good chin, but it’s actually your whole head. You get battered: left and right temples, forehead, nose, mouth, ears. The ears always hurt. Everyone looks at my biceps and the abs. But it’s your head that gets forgotten. What’s the best piece of advice that you would give to somebody who is trying to make it in boxing? I would tell them to talk to themselves and mentally prepare themselves.

You can always try to see a meditation specialist or a psychologist, but I think that the only way to test your greatness is to truly be in a position of adversity. You’re never going to find out how great you are by sitting on a beach. Boxers should talk to themselves more in the gym – build up those mental callouses. You’ve got to know that you are tough enough to get through this.

Murray returned to glory by channelling his will to achieve

David Clerihew

Andy Murray The Comeback Kid from Dunblane: 33-Years-Old, 190cm, 84kg

By Paul Wilson

At 5.09am on Saturday 4 August 2018, alone in a hotel bed in Washington, DC, two hours after he sobbed into his towel at the end of his first third-round win for a year, Andy Murray took a long, hard look into the black mirror of his iPhone and pressed record.

“It was a really emotional night for me, because I felt like I’m coming to the end and I’m really sad about that, because…” – his voice breaks, as he wipes tears from his eyes. “I really want to keep going but my body is telling me, ‘No.’ So… It hurts. And, yeah, I’m sorry that I can’t keep going.”

At the end of the 2016 tennis season, Murray was the world’s number one, the reigning Wimbledon champion and entering the imperial phase of his career. The following summer, a chronic hip problem got so bad that he couldn’t put on his shoes and socks. From there, he endured a two-year period during which he barely played, with two major surgeries, in January 2018 and January 2019 – the latter leaving him with a metal cap in his right hip socket.

“I think you look for miracles”

A week before that second op, there were more tears, this time in front of other people’s cameras at a press conference at the Australian Open, as he realised that the Grand Slam might be his last. (He lost his first-round match in five sets.) Tennis experts outside Murray’s circle thought he would never play again. Those inside knew that “never” is not in their man’s vocabulary.

“I think you look for miracles,” said Mark Bender, Murray’s physiotherapist, of competing at the top level with a metal hip. “But when you’ve got somebody who really wants to achieve and is going all-in, everybody buys into the hope that something magical can happen.” And, of course, it did.

Ten months after the DC dawn confessional, five after his second hip operation, Murray won the doubles at Queens in June 2019 and then the European Open in Antwerp in October – his first singles title for 30 months. After that, pelvic injury cut his year short. He hasn’t played in 2020.

Murray’s commitment to not merely return from setbacks but to excel makes him exceptional. He might well be enjoying (if that’s the right word) the current enforced lockdown – after all, there’s no pressure to be match-fit when there are no matches to play. But you can be sure that no one will be more determined to come back ready to play at the absolute best of his abilities.

Lewis Hamilton The Formula 1 Driver in Top Gear: 35-Years-Old, 174cm, 69kg

By Giuliano Donati

MH: Next season, you have the chance to match Michael Schumacher’s record of seven Formula 1 world championships. Nervous?

LH: I honestly don’t think about it much. I don’t want it to be a distraction. I’m currently the world champion but, every year, I start from scratch. I just want to be at the top of my game in a physical sense, just as I want my car to be the best in terms of engineering. How can I make sure I’m ahead of everyone else? How can I be more consistent, meticulous and precise? How can I better understand the technology? That’s what I focus on.

MH: What do you do to stay at the top, physically speaking?

LH: I like lifting weights, but I have to make sure that I don’t overdo it. Formula 1 drivers can’t be too heavy: more muscle means more kilos. It’s also disadvantageous to put too much muscle on your shoulders and arms, because you need to have a low centre of gravity in the car.

It’s important to have a good cardiovascular system as a driver. Over the course of a two-hour race, you might have an average heartbeat of 160-170bpm. During qualifying, it can go up to 190bpm. That’s why I do a lot of running. Sprints are a part of every workout.

MH: How has your training evolved since you started out in F1 almost 15 years ago?

LH: When I was young, I had a lot of energy and felt I could do anything. I didn’t have a strategy, and I didn’t stretch: I just got in the car and drove to win. But over the years, I’ve experimented with a number of different disciplines, like boxing and muay Thai. These days, I do lots of pilates, focusing on the core – the muscles beneath the muscles.

"I’m more mobile and in better shape than I was at 25"

MH: What’s your approach to nutrition?

LH: Three years ago, I decided to follow a plant-based diet. The only thing I regret is not having done it before. My taste buds have learned about things that I never thought I would eat and that I now love: falafel, avocado, beetroot, fresh and dried fruit. I’ve also noticed a marked improvement in my fitness level since I switched, which is motivating.

MH: So, you credit your plant-based diet with helping you stay at your peak?

LH: I was already at the top before changing my approach to food, but I was definitely struggling more and my energy was inconsistent. I had days when I felt strong and others when I was just sapped. When I switched to a plant-based diet, those highs and lows decreased significantly.

I’ve also noticed positive effects on my sleep and on my health in general. The benefits keep coming, and I’ve honestly never felt better. I’m 35 now, and though theoretically I should be less fit than before, I’m more mobile and in better shape than I was at 25.

Smart tweaks to nutrition and training have kept Hamilton in the fast lane

David Clerihew

MH: F1 is high octane, high adrenalin. How do you rest and recharge?

LH: Unplugging is a fundamental part of my routine. It’s so important to decompress after a race, so you can face the next one with a clear mind. I love spending time with my friends and family. Being with them helps me relax and focus my energy. But I can’t live without adrenalin. I love anything that makes my heart beat faster, whether that’s skiing, sky-diving, surfing or training.

MH: What are you most proud of achieving in your career?

LH: I was the first working-class Black F1 champion. I’m proud to have paved the way for others. One of my favourite phrases is: “You can’t be what you don’t see.” Anyone who sees me on the podium, even if it’s a child, can be inspired to follow their dreams. If that happens, I’ll have done my job well. Diversity is a problem that Formula 1 has to face up to. I want to do my part in helping the sport make progress, not only by inspiring others but also by collaborating to create more opportunities for people from different communities.

Mental discipline made Fraser the undisputed king of fitness

Hamish Brown

Mat Fraser Reigning CrossFit Games Champion: 30-Years-Old, 170cm, 88kg

By David Morton

MH: How are you managing to keep up with your training in lockdown?

MF: I’m in Kentucky right now with my friend and training partner [female CrossFit Games champion] Tia-Clair Toomey. With all of the gyms shut down, we thought we’d make the best of it and came out to a buddy’s lodge, which is usually used by rock climbers. We kinda just moved in and brought all our equipment with us. Our partners are here, too, so we’re just congregating as a big unit.

MH: You clearly have a tight network. You share the same agent, and Tia’s husband, Shane Orr, is your coach. How important is that set-up for you?

MF: It’s crucial. You’ve got to be surrounded by good people – people you belong with, who are like-minded. We’re in a unique situation, because we’ve been able to come together during this pandemic and train and hang out and go through this rollercoaster of emotions as a group. But current events aside, I know that I perform better when I’m happy and life is good.

Training with Tia didn’t just come about because we were located in the same place. I’ve been located in the same place as other training partners before, and it didn’t work out quite as well. I started working with Shane not because it was convenient, but because I liked what he was doing. Regardless of the fact that I was around him every day, I saw what he was doing, liked his demeanour, liked his attitude to everything. And most of all, I liked his programming.

The fact that we get along well as friends is just a bonus. The four of us all lived together before the Games last summer. That was a rare situation but it worked, and we had a great time doing it. We woke up every morning excited to put ourselves through what we had to go through. That’s always been the most important thing for me – keeping that good headspace while in training.

MH: Here in the UK, most people are having to train at home without the sort of kit you guys have. What would you do if you only had your bodyweight and a dumbbell or kettlebell?

MF: We actually try to use minimal equipment quite often, because it keeps you thinking outside the box. Yes, we have access to a lot of equipment, but we’ve been making sure that we keep changing it up with burpees, press-ups, air squats.

Whenever I train with bodyweight, I try to set it up as an EMOM [every minute, on the minute]. For me, those longer workouts are more of a mental barrier than a physical one. I know that I’m physically capable of it, but it’s whether it can keep my attention and keep me engaged for long enough to get a good workout in. So, I always put it into an EMOM, where you’re only looking at 40 seconds of work and 20 seconds’ rest before moving onto the next station. I’m only looking 40 seconds ahead, instead of being two or three rounds into a regular workout and thinking, “Oh, my gosh! I’ve still got 30 minutes left. I’m not even halfway!” With an EMOM, the light at the end of the tunnel is only 40 seconds away, and then you can have a sip of water or sit in front of a fan.

"Lifestyle stuff came to the fore: terrible diet, terrible sleep schedule, terrible attitude"

MH: You alluded to mental strength there. You finished second twice at the CrossFit Games, before going on your dominant run. What was it that changed? Do you think it was your mental game?

MF: I’d say it was half-mental and half-lifestyle. The first time I came second at the Games, I had no real idea what I was doing. You know, I was brand new to CrossFit and showing up at the gym when I could. I was a happy-go-lucky youngster, that first year.

The second year was when all of my lifestyle stuff came to the fore: terrible diet, terrible sleep schedule, terrible attitude mentally. I can’t say that my time in the gym wasn’t great. I hit huge PBs that year, but they were spontaneous, sporadic. I would show up at the gym and not know what deck of cards I was dealing with, whether I’d have enough energy to train, whether I’d be too tired, or whatever.

On top of that, I had a terrible attitude at the Games. If something didn’t go well, I would throttle back and just say, ‘This one’s not for me.’ After that, I took some steps. I started eating better; I committed myself to a good sleep schedule; I began doing some recovery work and warm-ups. Basically, everything I was supposed to be doing, I actually started doing.

And in competition, my attitude completely changed – seeing the benefit of a bad situation and managing to find a silver lining in it, instead of just being miserable and stewing.

MH: Now that you’ve won multiple times, you exude a sense of confidence when you compete. Do you still get nervous?

MF: If I wasn’t nervous, I’d be questioning whether I cared about what I was doing. I hate the way it feels, the immediate effect. Before most events, I dry-heave or throw up, because I’m so nervous. It’s not enjoyable. But at the same time, I know that I care and I still have that excitement. Backstage, people will see me dry-heaving and they look at my manager and say, “God, is Mat OK?” And he’s like, “Oh, yeah, he’s good. This is good.”

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

For Fraser, maintaining “a good headspace” is paramount – so he keeps his training varied with intense EMOM workouts

MH: Tia says that the reason you’re the world’s fittest man is your work ethic. She says that she’s never seen determination like it and that, in turn, it challenges her to get better every day.

MF: Well, the feeling is mutual. When I started training with Tia, it was immediately apparent that it was going to be different from any partnership I’d had before. She’s incredibly polished when she knows that people are watching, but she also has this aggressiveness that I’ve never seen in a female athlete.

We’re true training partners – gender never comes up. It’s almost like a mirror. I’ve never trained with anyone who has the same aggressiveness going into each and every workout, when it’s time to grind and you’re miserable and you’re not getting a pat on the back. You get to see someone’s true character when the conditions are less than ideal. You see this fight come out of her that you don’t see in many people.

MH: The Games season, as with all sports, is up in the air. At the moment, it seems that there will be a form of CrossFit Games, but on a smaller scale without fans. How do you feel about that?

MF: As long as the top people are there to compete against, it doesn’t matter. I have a soft spot for spectators who look forward to the event, and for sponsors and vendors, it’s their big opportunity, so it’s unfortunate. In the same breath, the whole world is dealing with a situation that we’ve never been in before. Everyone is understanding and everyone is dealing with the same problems. But as far as training goes, it’s business as usual.

Like all great sportsmen, Itoje has a powerful curiosity of mind

Hamish Brown

Maro Itoje The Thinking Man's Battering Ram: 25-Years-Old, 193cm, 155kg

By Ted Lane

Maro Itoje is not your average rugby player. This is the standard way profiles of the Saracens and England lock and flanker begin. Despite his size and talent, the reader is asked to marvel at his brain more than his biceps. It’s well known that his burgeoning rugby career dovetailed with a politics degree. He is revered as a gentle giant with a penchant for poetry. Hell, it’s even a trope we ran with ourselves after he arrived for a previous Men’s Health shoot carrying a book about the Nigerian civil war.

"He ended up having 74kg around his waist and doing a chin-up with ease"

But to gloss over his physique is to miss half the picture – half of what makes him a sporting powerhouse. Talking to the website Rugby Pass last year, Itoje’s Sarries colleague Alex Goode recounted a one-rep max test for chin-ups during one training session: “He came in, first day, and started on 20kg. He proceeded to go up and up and up. He was so unaware. He ended up having 74kg around his waist and doing a chin-up with ease. This is a guy a couple of days out of school.” Goode neglected to mention his own score.

Left to his own devices, Itoje likes beach weights. Training for fun means abs exercises and 21s, the quintessential biceps-building protocol. But disco muscles alone have not propelled him to the top of his sport. At Saracens, Itoje lifts three times a week. Monday is lower body, Tuesday is upper body, while Thursday is total body.

Mondays are most interesting because Andy Edwards, Saracens’ head of strength and conditioning, tweaks Itoje’s routine depending on where they are in the season. “His two main lifts are the trap bar deadlift for strength and the concentric squat for explosive strength,” he says. Low rep ranges are key. “If the priority is building strength, we’ll start with deadlifts. If the priority is being more explosive, it’s the concentric squat.”

Alternatively, if Edwards needs to maintain intensity at the business end of the season but reduce neural fatigue to avoid burnout, “We swap heavy deadlifts for weighted CMJs [counter-movement jumps], where Maro is jumping with a barbell on his back.”

Still, eventually, it’s Itoje’s mind that returns to the fore. “I’ve been at Saracens for 13 seasons and watched Maro develop from a kid,” says Edwards. “He’s always been the one to challenge me and ask: why? That craving for knowledge is unique to top sportsmen, and he’s got it.”

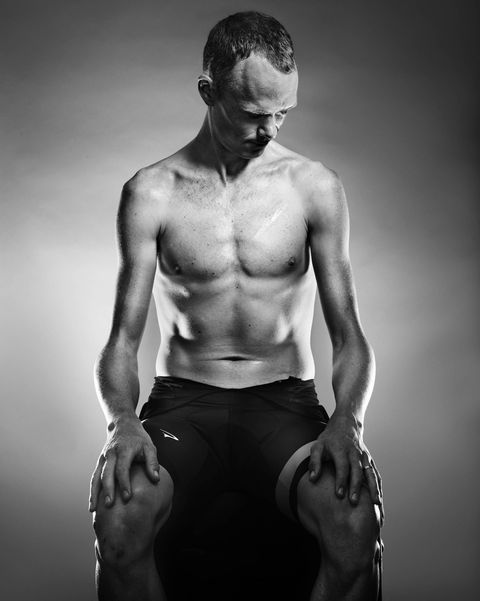

Chris Froome The Fastest (and Hardest) Man on Two Wheels: 35-Years-Old, 186cm, 66kg

By Paul Wilson

Chris Froome makes long-term and short-term targets central to his success. “I’m a forward thinker, always planning, sometimes way too far in advance,” he told Men’s Health in 2015, shortly before the second of his four Tour de France victories. “So, I enjoy reaching the smaller goals, which are motivating to reach the larger goals.” He could not have imagined that such targets would include “learn to walk again”, as they did after a horrific freak crash in June 2019.

On a recon of the time trial course at the Criterium du Dauphiné race in Roanne, France, gusty wind funnelled between buildings and took his front wheel just as he lifted a hand to clear his nostrils. Attempting to recover control, he veered off the road and into a wall, breaking his ribs, right femur, elbow, hip and sternum and the lowest vertebra in his neck. His team had clocked him at 54km per hour.

Such a calamitous accident was atypical in the extreme, and Froome’s rehabilitation came with many uncertainties. “It was progressive, really, because we just didn’t know how long it would take in terms of recovery,” said Froome’s coach, Tim Kerrison. “We had some different plans right at the beginning, but it’s been an ongoing review.” Not least because, despite the extent of his injuries, very quickly Froome began surpassing smaller comeback goals.

Seven weeks after the crash, it was said that he was “ahead of all predictions that were made initially of how long it would take to get to even this point”. In early August 2019, he was having three to four hours of physio every morning, then two hours of exercise after lunch. Afternoon shifts involved pedalling a stationary bike using only his left leg as his right leg healed, propped on a platform.

At the end of August, 10 weeks after the crash, he was doing track sessions on a bike; by the end of October, a team time trial at an exhibition race. In November, he had his final operation, which included removing from his right hip a 10-inch plate with screws as long as his thumb. In January this year, he joined a training camp with his beloved TeamINEOS. By February, he was performing on the UAE Tour –one that was unfortunately cut short by the pandemic – at which his stats were close to top-level.

“From that point on, it felt like everything was so positive.”

Upon reviving in intensive care in France, Froome was told by the surgeon that there was nothing to stop him making a 100% recovery. “That’s all I wanted to hear at that point,” he said later. “From that point on, it felt like everything was so positive.”

He immediately set a larger goal: to win the next Tour de France. At the time of writing this, despite some scepticism, that was scheduled to begin on 29 August. If it isn’t postponed, Froome will be 35 and very possibly in yellow-jersey form, having come back from – no hype, this – one of the worst injuries in his sport.

For Whitlock, playing the long game has meant becoming more strategic

Tom Watkins

Max Whitlock The Most Decorated Gymnast in Britain: 27-Years-Old, 167cm, 62.5kg

By Scarlett Wrench

Despite almost qualifying as a member of Generation Z, Max Whitlock is already a veteran of his sport. “Gymnastics is really demanding,” he says, by way of understatement. “A lot of people are already thinking about retiring by my age, because that’s when they start to struggle.” The lifespan of an Olympic gymnast is short, but while most burn out in their early-to-mid-twenties, Whitlock has no plans to fade away. Already the most decorated athlete in British gymnastics history, he has his sights set on Gold at the delayed Tokyo Games – then Paris 2024, too.

For Whitlock, playing the long game has meant tuning into his body’s signals. As a teenage prodigy, he could handle 35 hours of training per week; now, he has dropped it to a more “moderate” 20 hours of graft, split over six days. Whitlock has observed older gymnasts training like juniors and wearing themselves down. “I’m hoping I’ll never burn out, because I’m careful not to push myself too far,” he says. “I do what I need to – and what I know I can recover from – so the next day is always productive.”

His training is very specific to his sport. What most people consider “cardio” is of little use. He might run once a week in the build-up to a competition, “but it’s just a mile done as quickly as possible. We’re only on the apparatus for a minute and a half to two minutes. So, it’s still targeted.”

He doesn’t lift weights, either – it doesn’t build the sort of strength he needs. Conditioning workouts are purely bodyweight-based, incorporating handstand variations, ring work, triceps dips, wide-arm press-ups and leg lifts. “I also do a lot of joint-strengthening exercises to make sure my wrists and ankles are ready for my session,” he says. “As I’m getting older, my joints need more attention.” Staying leaner and lighter also helps with longevity. Excess muscle mass would hinder his flexibility.

1 note

·

View note

Text

9 Professional Athletes Share The Workout and Fitness Tips That Got Them to the Top

New Post has been published on https://vip.anthonyjoshua.club/9-professional-athletes-share-the-workout-and-fitness-tips-that-got-them-to-the-top/

9 Professional Athletes Share The Workout and Fitness Tips That Got Them to the Top

As a reader of Men’s Health, it would seem a fair assumption that you know what’s required to stay healthy, both in body and mind. Less known, however, is how the men and women at an elite level keep themselves at the top of their game for years — sometimes decades — on end, surpassing feats that previously weren’t thought possible.

Below, we’ve compiled nine case studies from our annual Body Issue, an edition of Men’s Health that celebrates a tapestry of world-beating champions, each with a body that’s built for purpose — whether that’s running 26.2 miles in under two hours, hoarding gold medals at the Olympics or being crowned The Fittest Man on Earth consecutively for four years. This is what it takes to reach the top.

DAVID CLERIHEW

Eliud Kipchoge

The Greatest Marathon Runner of All Time: 35-Years-

Old, 170cm, 56kg

In most sports, the issue of who is the GOAT is a matter of endless contention. In the world of long-distance running, however, there is simply no dispute: Eliud Kipchoge is the most extraordinary athlete over a distance of 26.2 miles that the world has ever seen.

In 2012, the remarkable Kenyan finished his first half-marathon in under an hour, the third-fastest debut ever. A year later, he won his first marathon in Hamburg, beating the field by more than two minutes and setting a course record.

For his first major in Berlin, just a few months on, he came second behind former world-record holder Wilson Kipsang. Even then, he still posted the fifth-fastest time in history. Since that relative disappointment, he has won every marathon he’s run on the world stage, including the gold medal at the Rio Olympics. That’s 11 in a row, including Berlin and London four times.

Then, last October in Vienna, Kipchoge set out to achieve the impossible. The sub-two-hour marathon had been mythologised possibly even more than the four-minute mile. He had trained relentlessly, clocking 140 miles per week, combining punishing speed sessions and strength training, all at high altitudes. But it was perhaps Kipchoge’s mental strength that proved decisive in Austria.“Some people believe it is impossible,” he said before the event. “My team and I believe it is possible. We will prove them wrong.” When Kipchoge broke the tape in Vienna, one hour, 59 minutes and 40 seconds after he started, he not only proved his doubters wrong – he turned a collective dream into reality.

“I believe in a calm, simple and low-profile life. You live simply, you train hard”

“It’s not just the speed at which he runs and the incredible endurance that sustains him,” says Rick Pearson, senior editor of Runner’s World. “It’s the way he does it. Kipchoge’s running style is a thing of beauty – pure poetry in motion. It’s smooth, it’s serene, there’s no wasted effort. And somehow, he tops it all off with a megawatt smile.”

Indeed, what makes Kipchoge’s achievements all the more astounding is his humility. In between running, he works on the family farm, collecting and chopping vegetables. “In life, the idea is to be happy,” he says. “So, I believe in a calm, simple and low-profile life. You live simply, you train hard, and you live an honest life. Then you are free.”

Adam Peaty

The Leviathan of the Olympic Pool: 25-Years_old, 191cm, 93kg

Hitting the pool is a tranquil way to boost fitness and sink stress – at least, it is for ordinary men. Olympic gold medallist Adam Peaty takes a more combative approach. “I love the aggression of racing,” he says. “You have to be very composed when you’re swimming, but I use that composure in an angry way.” If you’ve been following Peaty on Instagram during the lockdown, you will have seen him repping out parallette press-ups in a weighted vest, wearing all black and sporting a quarantine buzz cut. This militant aesthetic only serves to reinforce the brutality of his workouts.

This focused aggression has yielded exceptional results. As well as becoming the first male British swimmer to win the gold medal in the 100m breaststroke for 24 years at the 2016 Olympics in Rio, Peaty has set 11 swimming world records. He became the first man to break the hallowed 58-second mark in the same event. Then he broke the 57-second mark.

“In the water, all of this comes from your core – it powers every stroke.”

“Adam has got reality distortion,” says coach and 2004 Olympian Mel Marshall. “He doesn’t see limits – he just sees opportunities.” Which comes in handy when Marshall floods his week with a staggering workload, both in the pool and on dry land. Peaty swims a breathtaking 50km each week; 5km in the morning, 5km in the afternoon, Monday to Friday. But it’s far from a mind-numbing slog. “Tuesday afternoon is intense,” says Marshall. “He does 40 25m reps – each one in 60 seconds. That’s 12 seconds of sprinting, 50-ish seconds of recovery, 40 times.”

It may lack a barbell, but it’s an EMOM workout to make you wince. “His other high-intensity session is 20 100m reps: four reps at lactate threshold [30bpm below his maximum heart rate], with one recovery, then three reps at his VO max [10bpm below his maximum heart rate], with two recovery, and repeat.” And that’s just his pool work.

Peaty’s gym sessions dovetail with his water-based workouts. On Mondays, he follows up a kick-based pool session with an upper-body shift pumping iron. There’s a lot of core work, too. “On dry land, you have the ground to offer stability and provide leverage for movement,” says Marshall. “In the water, all of this comes from your core – it powers every stroke.”

By his own admission, Peaty is intensely competitive – fiercely, even. But it’s his ability to absorb the workload that sets him apart. “He recovers incredibly quickly and he adapts incredibly quickly,” says Marshall. Curiously, his coach feels that it’s the foundations laid in the gym early on that are ultimately responsible for his success.

“Starting young means he can take advantage of all of those hormones coursing through his body,” says Marshall. “And those benefits then continue. The man is a workhorse.” Which is bad news for those playing catch-up before the next Olympics.

Joshua reclaimed all he had lost by learning to play to his strengths

Anthony Joshua

Unified Heavyweight Boxing Champion: 30-Years-Old, 198cm, 108kg

Men’s Health: Last December, you went into your second fight with Andy Ruiz with a noticeably different game plan to when you lost your titles – WBA, IBF, WBO and IBO – to him earlier in 2019. Was that the key to winning your belts back?

AJ: I think it’s all about adapting. Different circumstances require different preparation. It was the same war, but I had learned a lot from the first battle. Ruiz isn’t the type of fighter that you go head to head with. For the first fight, I was planning on going in there and trading with him. But there’s an old boxing saying: “You don’t hook with a hooker!” So, what did I do? I went in there and hooked with a hooker and the actual hooker came out on top.In the second fight, I went in there and he tried to box with a boxer. And I came out on top. I had to learn what my strengths were and what his weaknesses were, and then I just boxed to those. That’s your basic foundation: never play to someone else’s strengths. In anything you do, everyone has their own strengths. If you play to theirs rather than yours, they are always going to come off better than you in the long run. This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

MH: You weighed in almost 5kg lighter for the second fight and were under 108kg for the first time since 2014. How did you adapt your training to come in so visibly leaner?

AJ: Ha, ha! You want me to give away my secrets? You’ve just got to be specific. Training is all about what you’re trying to achieve. To prepare for 12 rounds of boxing, it sounds obvious, but you’ve got to box, box, box. And that’s what we did.

There’s not much point boxing and then spending time in the swimming pool to build endurance, because all you’re doing is building swimming endurance. The same goes for boxing a little bit and then spending hours lifting weights, because that’s for weightlifters. The best boxing stamina work you can do is to hit the heavy bag or shadow box. Everything that involves boxing without getting injured is the best form of training.

It’s a simple thing that’s easy to overlook. If you want to get good at something, do that thing. Focus on it. We try to add this and that, strip it back. But you need to box more if you want to be in shape for boxing.

Joshua found success in stripping back his approach

MH: In what way did you change your nutrition? Is it true that Wladimir Klitschko advised you to reduce your salt intake?

AJ: I did cut out salt leading up to that fight. But the food was so bland! You don’t realise how much we depend on salts and sugars. When you remove them, you realise what the true taste of food is like. It had a real benefit, though, because it stripped my body of all the excess sugar and salt I didn’t need, and I managed to lose a shedload of weight.

Chicken and broccoli are tough when you can’t put any spice on them. Someone said to me that it’s not the chicken we like – it’s the spice and the sauces. That’s why I think vegetarians and vegans are onto something. We’re not meant to like chicken. They put the same sauces and spices on vegetables and get that taste and texture.

MH: What’s your diet like coming up to a weigh-in for a fight?

AJ: It’s pretty spot on. Weigh-in is usually about 2pm, so I will have had breakfast and lunch by then. Luckily, I don’t have to “make” weight, so I just continue my preparations like it’s another day. I don’t prepare for the scales; I just use it as an opportunity to showcase my work ethic and how hard I’ve been training.

MH: All boxers come in for criticism on social media. How do you handle negative comments or haters?

AJ: I think that it’s hard to ignore it. I’m not going to lie and say that I don’t pay attention to any of that, because it’s impossible not to see it. I started my social media on my own and, even though it has turned into a business page, I still handle a lot of it myself. I think that it’s fine to have doubters, as long as you don’t believe what they’re saying the whole time. You have to prove your doubters wrong. When they don’t believe, you should always believe.

“You’ve got to be specific: training is all about what you are trying to achieve”

The doubters aren’t always bad, either. You just have to try to find something positive out of it. They might say, “You’re shit, and you’re going to get knocked out because your hands are too low” – and I would think, “That’s a good indication I’ve got to keep my left hand up.” I use the doubters as a positive factor, not as a negative one.

MH: You’ve occasionally been called out for being more of an aesthete than an athlete. What do you think is the most underrated part of a boxer’s physique?

AJ: Their head! That’s where you take the most punishment. Everyone says it’s all about a good chin, but it’s actually your whole head. You get battered: left and right temples, forehead, nose, mouth, ears. The ears always hurt. Everyone looks at my biceps and the abs. But it’s your head that gets forgotten. What’s the best piece of advice that you would give to somebody who is trying to make it in boxing? I would tell them to talk to themselves and mentally prepare themselves.

You can always try to see a meditation specialist or a psychologist, but I think that the only way to test your greatness is to truly be in a position of adversity. You’re never going to find out how great you are by sitting on a beach. Boxers should talk to themselves more in the gym – build up those mental callouses. You’ve got to know that you are tough enough to get through this.

Murray returned to glory by channelling his will to achieve

Andy Murray

The Comeback Kid from Dunblane: 33-Years-Old, 190cm, 84kg

At 5.09am on Saturday 4 August 2018, alone in a hotel bed in Washington, DC, two hours after he sobbed into his towel at the end of his first third-round win for a year, Andy Murray took a long, hard look into the black mirror of his iPhone and pressed record.

“It was a really emotional night for me, because I felt like I’m coming to the end and I’m really sad about that, because…” – his voice breaks, as he wipes tears from his eyes. “I really want to keep going but my body is telling me, ‘No.’ So… It hurts. And, yeah, I’m sorry that I can’t keep going.”

At the end of the 2016 tennis season, Murray was the world’s number one, the reigning Wimbledon champion and entering the imperial phase of his career. The following summer, a chronic hip problem got so bad that he couldn’t put on his shoes and socks. From there, he endured a two-year period during which he barely played, with two major surgeries, in January 2018 and January 2019 – the latter leaving him with a metal cap in his right hip socket.

“I think you look for miracles”

A week before that second op, there were more tears, this time in front of other people’s cameras at a press conference at the Australian Open, as he realised that the Grand Slam might be his last. (He lost his first-round match in five sets.) Tennis experts outside Murray’s circle thought he would never play again. Those inside knew that “never” is not in their man’s vocabulary.

“I think you look for miracles,” said Mark Bender, Murray’s physiotherapist, of competing at the top level with a metal hip. “But when you’ve got somebody who really wants to achieve and is going all-in, everybody buys into the hope that something magical can happen.” And, of course, it did.

Ten months after the DC dawn confessional, five after his second hip operation, Murray won the doubles at Queens in June 2019 and then the European Open in Antwerp in October – his first singles title for 30 months. After that, pelvic injury cut his year short. He hasn’t played in 2020.

Murray’s commitment to not merely return from setbacks but to excel makes him exceptional. He might well be enjoying (if that’s the right word) the current enforced lockdown – after all, there’s no pressure to be match-fit when there are no matches to play. But you can be sure that no one will be more determined to come back ready to play at the absolute best of his abilities.

Lewis Hamilton The Formula 1 Driver in Top Gear: 35-Years-Old, 174cm, 69kg Interview: MH: Next season, you have the chance to match Michael Schumacher’s record of seven Formula 1 world championships. Nervous? LH: I honestly don’t think about it much. I don’t want it to be a distraction. I’m currently the world champion but, every year, I start from scratch. I just want to be at the top of my game in a physical sense, just as I want my car to be the best in terms of engineering. How can I make sure I’m ahead of everyone else? How can I be more consistent, meticulous and precise? How can I better understand the technology? That’s what I focus on. MH: What do you do to stay at the top, physically speaking? LH: I like lifting weights, but I have to make sure that I don’t overdo it. Formula 1 drivers can’t be too heavy: more muscle means more kilos. It’s also disadvantageous to put too much muscle on your shoulders and arms, because you need to have a low center of gravity in the car. It’s important to have a good cardiovascular system as a driver. Over the course of a two-hour race, you might have an average heartbeat of 160-170bpm. During qualifying, it can go up to 190bpm. That’s why I do a lot of running. Sprints are a part of every workout. MH: How has your training evolved since you started out in F1 almost 15 years ago? LH: When I was young, I had a lot of energy and felt I could do anything. I didn’t have a strategy, and I didn’t stretch: I just got in the car and drove to win. But over the years, I’ve experimented with a number of different disciplines, like boxing and may Thai. These days, I do lots of Pilates, focusing on the core – the muscles beneath the muscles. “I’m more mobile and in better shape than I was at 25” MH: What’s your approach to nutrition? LH: Three years ago, I decided to follow a plant-based diet. The only thing I regret is not having done it before. My taste buds have learned about things that I never thought I would eat and that I now love: falafel, avocado, beetroot, fresh and dried fruit. I’ve also noticed a marked improvement in my fitness level since I switched, which is motivating. MH: So, you credit your plant-based diet with helping you stay at your peak? LH: I was already at the top before changing my approach to food, but I was definitely struggling more and my energy was inconsistent. I had days when I felt strong and others when I was just sapped. When I switched to a plant-based diet, those highs and lows decreased significantly. I’ve also noticed positive effects on my sleep and on my health in general. The benefits keep coming, and I’ve honestly never felt better. I’m 35 now, and though theoretically I should be less fit than before, I’m more mobile and in better shape than I was at 25.

Smart tweaks to nutrition and training have kept Hamilton in the fast lane MH: F1 is high octane, high adrenalin. How do you rest and recharge? LH: Unplugging is a fundamental part of my routine. It’s so important to decompress after a race, so you can face the next one with a clear mind. I love spending time with my friends and family. Being with them helps me relax and focus my energy. But I can’t live without adrenalin. I love anything that makes my heart beat faster, whether that’s skiing, sky-diving, surfing or training. MH: What are you most proud of achieving in your career? LH: I was the first working-class Black F1 champion. I’m proud to have paved the way for others. One of my favorite phrases is: “You can’t be what you don’t see.” Anyone who sees me on the podium, even if it’s a child, can be inspired to follow their dreams. If that happens, I’ll have done my job well. Diversity is a problem that Formula 1 has to face up to. I want to do my part in helping the sport make progress, not only by inspiring others but also by collaborating to create more opportunities for people from different communities.

Mental discipline made Fraser the undisputed king of fitness HAMISH BROWN MH: How are you managing to keep up with your training in lockdown? MF: I’m in Kentucky right now with my friend and training partner [female CrossFit Games champion] Tia-Clair Toomey. With all of the gyms shut down, we thought we’d make the best of it and came out to a buddy’s lodge, which is usually used by rock climbers. We kinda just moved in and brought all our equipment with us. Our partners are here, too, so we’re just congregating as a big unit. MH: You clearly have a tight network. You share the same agent, and Tia’s husband, Shane Orr, is your coach. How important is that set-up for you? MF: It’s crucial. You’ve got to be surrounded by good people – people you belong with, who are like-minded. We’re in a unique situation, because we’ve been able to come together during this pandemic and train and hang out and go through this rollercoaster of emotions as a group. But current events aside, I know that I perform better when I’m happy and life is good. Training with Tia didn’t just come about because we were located in the same place. I’ve been located in the same place as other training partners before, and it didn’t work out quite as well. I started working with Shane not because it was convenient, but because I liked what he was doing. Regardless of the fact that I was around him every day, I saw what he was doing, liked his demeanor, liked his attitude to everything. And most of all, I liked his programming. The fact that we get along well as friends is just a bonus. The four of us all lived together before the Games last summer. That was a rare situation but it worked, and we had a great time doing it. We woke up every morning excited to put ourselves through what we had to go through. That’s always been the most important thing for me – keeping that good headspace while in training. MH: Here in the UK, most people are having to train at home without the sort of kit you guys have. What would you do if you only had your bodyweight and a dumbbell or kettlebell? MF: We actually try to use minimal equipment quite often, because it keeps you thinking outside the box. Yes, we have access to a lot of equipment, but we’ve been making sure that we keep changing it up with burpees, press-ups, air squats. Whenever I train with bodyweight, I try to set it up as an EMOM [every minute, on the minute]. For me, those longer workouts are more of a mental barrier than a physical one. I know that I’m physically capable of it, but it’s whether it can keep my attention and keep me engaged for long enough to get a good workout in. So, I always put it into an EMOM, where you’re only looking at 40 seconds of work and 20 seconds’ rest before moving onto the next station. I’m only looking 40 seconds ahead, instead of being two or three rounds into a regular workout and thinking, “Oh, my gosh! I’ve still got 30 minutes left. I’m not even halfway!” With an EMOM, the light at the end of the tunnel is only 40 seconds away, and then you can have a sip of water or sit in front of a fan. “Lifestyle stuff came to the fore: terrible diet, terrible sleep schedule, terrible attitude” MH: You alluded to mental strength there. You finished second twice at the CrossFit Games, before going on your dominant run. What was it that changed? Do you think it was your mental game? MF: I’d say it was half-mental and half-lifestyle. The first time I came second at the Games, I had no real idea what I was doing. You know, I was brand new to CrossFit and showing up at the gym when I could. I was a happy-go-lucky youngster, that first year. The second year was when all of my lifestyle stuff came to the fore: terrible diet, terrible sleep schedule, terrible attitude mentally. I can’t say that my time in the gym wasn’t great. I hit huge PBs that year, but they were spontaneous, sporadic. I would show up at the gym and not know what deck of cards I was dealing with, whether I’d have enough energy to train, whether I’d be too tired, or whatever. ADVERTISEMENT – CONTINUE READING BELOW On top of that, I had a terrible attitude at the Games. If something didn’t go well, I would throttle back and just say, ‘This one’s not for me.’ After that, I took some steps. I started eating better; I committed myself to a good sleep schedule; I began doing some recovery work and warm-ups. Basically, everything I was supposed to be doing, I actually started doing. And in competition, my attitude completely changed – seeing the benefit of a bad situation and managing to find a silver lining in it, instead of just being miserable and stewing. MH: Now that you’ve won multiple times, you exude a sense of confidence when you compete. Do you still get nervous? MF: If I wasn’t nervous, I’d be questioning whether I cared about what I was doing. I hate the way it feels, the immediate effect. Before most events, I dry-heave or throw up, because I’m so nervous. It’s not enjoyable. But at the same time, I know that I care and I still have that excitement. Backstage, people will see me dry-heaving and they look at my manager and say, “God, is Mat OK?” And he’s like, “Oh, yeah, he’s good. This is good.” This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

For Fraser, maintaining “a good headspace” is paramount – so he keeps his training varied with intense EMOM workouts MH: Tia says that the reason you’re the world’s fittest man is your work ethic. She says that she’s never seen determination like it and that, in turn, it challenges her to get better every day. MF: Well, the feeling is mutual. When I started training with Tia, it was immediately apparent that it was going to be different from any partnership I’d had before. She’s incredibly polished when she knows that people are watching, but she also has this aggressiveness that I’ve never seen in a female athlete. We’re true training partners – gender never comes up. It’s almost like a mirror. I’ve never trained with anyone who has the same aggressiveness going into each and every workout, when it’s time to grind and you’re miserable and you’re not getting a pat on the back. You get to see someone’s true character when the conditions are less than ideal. You see this fight come out of her that you don’t see in many people. ADVERTISEMENT – CONTINUE READING BELOW MH: The Games season, as with all sports, is up in the air. At the moment, it seems that there will be a form of CrossFit Games, but on a smaller scale without fans. How do you feel about that? MF: As long as the top people are there to compete against, it doesn’t matter. I have a soft spot for spectators who look forward to the event, and for sponsors and vendors, it’s their big opportunity, so it’s unfortunate. In the same breath, the whole world is dealing with a situation that we’ve never been in before. Everyone is understanding and everyone is dealing with the same problems. But as far as training goes, it’s business as usual.

Maro Itoje The Thinking Man’s Battering Ram: 25-Years-Old, 193cm, 155kg Maro Itoje is not your average rugby player. This is the standard way profiles of the Saracens and England lock and flanker begin. Despite his size and talent, the reader is asked to marvel at his brain more than his biceps. It’s well known that his burgeoning rugby career dovetailed with a politics degree. He is revered as a gentle giant with a penchant for poetry. Hell, it’s even a trope we ran with ourselves after he arrived for a previous Men’s Health shoot carrying a book about the Nigerian civil war. “He ended up having 74kg around his waist and doing a chin-up with ease” But to gloss over his physique is to miss half the picture – half of what makes him a sporting powerhouse. Talking to the website Rugby Pass last year, Itoje’s Sarries colleague Alex Goode recounted a one-rep max test for chin-ups during one training session: “He came in, first day, and started on 20kg. He proceeded to go up and up and up. He was so unaware. He ended up having 74kg around his waist and doing a chin-up with ease. This is a guy a couple of days out of school.” Goode neglected to mention his own score. Left to his own devices, Itoje likes beach weights. Training for fun means abs exercises and 21s, the quintessential biceps-building protocol. But disco muscles alone have not propelled him to the top of his sport. At Saracens, Itoje lifts three times a week. Monday is lower body, Tuesday is upper body, while Thursday is total body. Mondays are most interesting because Andy Edwards, Saracens’ head of strength and conditioning, tweaks Itoje’s routine depending on where they are in the season. “His two main lifts are the trap bar deadlift for strength and the concentric squat for explosive strength,” he says. Low rep ranges are key. “If the priority is building strength, we’ll start with deadlifts. If the priority is being more explosive, it’s the concentric squat.” How England Rugby’s Maro Itoje Built His Body Alternatively, if Edwards needs to maintain intensity at the business end of the season but reduce neural fatigue to avoid burnout, “We swap heavy deadlifts for weighted CMJs [counter-movement jumps], where Maro is jumping with a barbell on his back.” Still, eventually, it’s Itoje’s mind that returns to the fore. “I’ve been at Saracens for 13 seasons and watched Maro develop from a kid,” says Edwards. “He’s always been the one to challenge me and ask: why? That craving for knowledge is unique to top sportsmen, and he’s got it.”

DAVID CLERIHEW

DAVID (PRIVATE) CLERIHEW The Fastest (and Hardest) Man on Two Wheels: 35-Years-Old, 186cm, 66kg Chris Froome makes long-term and short-term targets central to his success. “I’m a forward thinker, always planning, sometimes way too far in advance,” he told Men’s Health in 2015, shortly before the second of his four Tour de France victories. “So, I enjoy reaching the smaller goals, which are motivating to reach the larger goals.” He could not have imagined that such targets would include “learn to walk again”, as they did after a horrific freak crash in June 2019. On a recon of the time trial course at the Criterium du Dauphiné race in Roanne, France, gusty wind funneled between buildings and took his front wheel just as he lifted a hand to clear his nostrils. Attempting to recover control, he veered off the road and into a wall, breaking his ribs, right femur, elbow, hip and sternum and the lowest vertebra in his neck. His team had clocked him at 54km per hour. Such a calamitous accident was atypical in the extreme, and Froome’s rehabilitation came with many uncertainties. “It was progressive, really, because we just didn’t know how long it would take in terms of recovery,” said Froome’s coach, Tim Kerrison. “We had some different plans right at the beginning, but it’s been an ongoing review.” Not least because, despite the extent of his injuries, very quickly Froome began surpassing smaller comeback goals. Seven weeks after the crash, it was said that he was “ahead of all predictions that were made initially of how long it would take to get to even this point”. In early August 2019, he was having three to four hours of physio every morning, then two hours of exercise after lunch. Afternoon shifts involved pedaling a stationary bike using only his left leg as his right leg healed, propped on a platform. At the end of August, 10 weeks after the crash, he was doing track sessions on a bike; by the end of October, a team time trial at an exhibition race. In November, he had his final operation, which included removing from his right hip a 10-inch plate with screws as long as his thumb. In January this year, he joined a training camp with his beloved Team INEOS. By February, he was performing on the UAE Tour –one that was unfortunately cut short by the pandemic – at which his stats were close to top-level. “From that point on, it felt like everything was so positive.” Upon reviving in intensive care in France, Froome was told by the surgeon that there was nothing to stop him making a 100% recovery. “That’s all I wanted to hear at that point,” he said later. “From that point on, it felt like everything was so positive.” He immediately set a larger goal: to win the next Tour de France. At the time of writing this, despite some scepticism, that was scheduled to begin on 29 August. If it isn’t postponed, Froome will be 35 and very possibly in yellow-jersey form, having come back from – no hype, this – one of the worst injuries in his sport.

For Whitlock, playing the long game has meant becoming more strategic TOM WATKINS Max Whitlock The Most Decorated Gymnast in Britain: 27-Years-Old, 167cm, 62.5kg Despite almost qualifying as a member of Generation Z, Max Whitlock is already a veteran of his sport. “Gymnastics is really demanding,” he says, by way of understatement. “A lot of people are already thinking about retiring by my age, because that’s when they start to struggle.” The lifespan of an Olympic gymnast is short, but while most burn out in their early-to-mid-twenties, Whitlock has no plans to fade away. Already the most decorated athlete in British gymnastics history, he has his sights set on Gold at the delayed Tokyo Games – then Paris 2024, too. Why Max Whitlock Has Adapted His Training For Whitlock, playing the long game has meant tuning into his body’s signals. As a teenage prodigy, he could handle 35 hours of training per week; now, he has dropped it to a more “moderate” 20 hours of graft, split over six days. Whitlock has observed older gymnasts training like juniors and wearing themselves down. “I’m hoping I’ll never burn out, because I’m careful not to push myself too far,” he says. “I do what I need to – and what I know I can recover from – so the next day is always productive.” His training is very specific to his sport. What most people consider “cardio” is of little use. He might run once a week in the build-up to a competition, “but it’s just a mile done as quickly as possible. We’re only on the apparatus for a minute and a half to two minutes. So, it’s still targeted.” Max Whitlock Shares His Daily Meal Plan He doesn’t lift weights, either – it doesn’t build the sort of strength he needs. Conditioning workouts are purely bodyweight-based, incorporating handstand variations, ring work, triceps dips, wide-arm press-ups and leg lifts. “I also do a lot of joint-strengthening exercises to make sure my wrists and ankles are ready for my session,” he says. “As I’m getting older, my joints need more attention.” Staying leaner and lighter also helps with longevity. Excess muscle mass would hinder his flexibility. With an unanticipated additional 12 months to hone his Olympic routine, Whitlock’s focus is now on consistency and consolidation. “I was still adding in new skills last year, which is quite late,” he says. “My target is to keep [my routine] at the highest level of difficulty in the world. That way, I’ll always be in a position to gain the title. That’s my mindset.”

0 notes

Text

9 Professional Athletes Share The Workout and Fitness Tips That Got Them to the Top

New Post has been published on https://vip.anthonyjoshua.club/9-professional-athletes-share-the-workout-and-fitness-tips-that-got-them-to-the-top/

9 Professional Athletes Share The Workout and Fitness Tips That Got Them to the Top

As a reader of Men’s Health, it would seem a fair assumption that you know what’s required to stay healthy, both in body and mind. Less known, however, is how the men and women at an elite level keep themselves at the top of their game for years — sometimes decades — on end, surpassing feats that previously weren’t thought possible.

Below, we’ve compiled nine case studies from our annual Body Issue, an edition of Men’s Health that celebrates a tapestry of world-beating champions, each with a body that’s built for purpose — whether that’s running 26.2 miles in under two hours, hoarding gold medals at the Olympics or being crowned The Fittest Man on Earth consecutively for four years. This is what it takes to reach the top.

DAVID CLERIHEW

Eliud Kipchoge

The Greatest Marathon Runner of All Time: 35-Years-

Old, 170cm, 56kg

In most sports, the issue of who is the GOAT is a matter of endless contention. In the world of long-distance running, however, there is simply no dispute: Eliud Kipchoge is the most extraordinary athlete over a distance of 26.2 miles that the world has ever seen.

In 2012, the remarkable Kenyan finished his first half-marathon in under an hour, the third-fastest debut ever. A year later, he won his first marathon in Hamburg, beating the field by more than two minutes and setting a course record.

For his first major in Berlin, just a few months on, he came second behind former world-record holder Wilson Kipsang. Even then, he still posted the fifth-fastest time in history. Since that relative disappointment, he has won every marathon he’s run on the world stage, including the gold medal at the Rio Olympics. That’s 11 in a row, including Berlin and London four times.

Then, last October in Vienna, Kipchoge set out to achieve the impossible. The sub-two-hour marathon had been mythologised possibly even more than the four-minute mile. He had trained relentlessly, clocking 140 miles per week, combining punishing speed sessions and strength training, all at high altitudes. But it was perhaps Kipchoge’s mental strength that proved decisive in Austria.“Some people believe it is impossible,” he said before the event. “My team and I believe it is possible. We will prove them wrong.” When Kipchoge broke the tape in Vienna, one hour, 59 minutes and 40 seconds after he started, he not only proved his doubters wrong – he turned a collective dream into reality.

“I believe in a calm, simple and low-profile life. You live simply, you train hard”

“It’s not just the speed at which he runs and the incredible endurance that sustains him,” says Rick Pearson, senior editor of Runner’s World. “It’s the way he does it. Kipchoge’s running style is a thing of beauty – pure poetry in motion. It’s smooth, it’s serene, there’s no wasted effort. And somehow, he tops it all off with a megawatt smile.”

Indeed, what makes Kipchoge’s achievements all the more astounding is his humility. In between running, he works on the family farm, collecting and chopping vegetables. “In life, the idea is to be happy,” he says. “So, I believe in a calm, simple and low-profile life. You live simply, you train hard, and you live an honest life. Then you are free.”

Adam Peaty

The Leviathan of the Olympic Pool: 25-Years_old, 191cm, 93kg

Hitting the pool is a tranquil way to boost fitness and sink stress – at least, it is for ordinary men. Olympic gold medallist Adam Peaty takes a more combative approach. “I love the aggression of racing,” he says. “You have to be very composed when you’re swimming, but I use that composure in an angry way.” If you’ve been following Peaty on Instagram during the lockdown, you will have seen him repping out parallette press-ups in a weighted vest, wearing all black and sporting a quarantine buzz cut. This militant aesthetic only serves to reinforce the brutality of his workouts.

This focused aggression has yielded exceptional results. As well as becoming the first male British swimmer to win the gold medal in the 100m breaststroke for 24 years at the 2016 Olympics in Rio, Peaty has set 11 swimming world records. He became the first man to break the hallowed 58-second mark in the same event. Then he broke the 57-second mark.

“In the water, all of this comes from your core – it powers every stroke.”

“Adam has got reality distortion,” says coach and 2004 Olympian Mel Marshall. “He doesn’t see limits – he just sees opportunities.” Which comes in handy when Marshall floods his week with a staggering workload, both in the pool and on dry land. Peaty swims a breathtaking 50km each week; 5km in the morning, 5km in the afternoon, Monday to Friday. But it’s far from a mind-numbing slog. “Tuesday afternoon is intense,” says Marshall. “He does 40 25m reps – each one in 60 seconds. That’s 12 seconds of sprinting, 50-ish seconds of recovery, 40 times.”

It may lack a barbell, but it’s an EMOM workout to make you wince. “His other high-intensity session is 20 100m reps: four reps at lactate threshold [30bpm below his maximum heart rate], with one recovery, then three reps at his VO max [10bpm below his maximum heart rate], with two recovery, and repeat.” And that’s just his pool work.

Peaty’s gym sessions dovetail with his water-based workouts. On Mondays, he follows up a kick-based pool session with an upper-body shift pumping iron. There’s a lot of core work, too. “On dry land, you have the ground to offer stability and provide leverage for movement,” says Marshall. “In the water, all of this comes from your core – it powers every stroke.”

By his own admission, Peaty is intensely competitive – fiercely, even. But it’s his ability to absorb the workload that sets him apart. “He recovers incredibly quickly and he adapts incredibly quickly,” says Marshall. Curiously, his coach feels that it’s the foundations laid in the gym early on that are ultimately responsible for his success.

“Starting young means he can take advantage of all of those hormones coursing through his body,” says Marshall. “And those benefits then continue. The man is a workhorse.” Which is bad news for those playing catch-up before the next Olympics.

Joshua reclaimed all he had lost by learning to play to his strengths

Anthony Joshua

Unified Heavyweight Boxing Champion: 30-Years-Old, 198cm, 108kg

Men’s Health: Last December, you went into your second fight with Andy Ruiz with a noticeably different game plan to when you lost your titles – WBA, IBF, WBO and IBO – to him earlier in 2019. Was that the key to winning your belts back?

AJ: I think it’s all about adapting. Different circumstances require different preparation. It was the same war, but I had learned a lot from the first battle. Ruiz isn’t the type of fighter that you go head to head with. For the first fight, I was planning on going in there and trading with him. But there’s an old boxing saying: “You don’t hook with a hooker!” So, what did I do? I went in there and hooked with a hooker and the actual hooker came out on top.In the second fight, I went in there and he tried to box with a boxer. And I came out on top. I had to learn what my strengths were and what his weaknesses were, and then I just boxed to those. That’s your basic foundation: never play to someone else’s strengths. In anything you do, everyone has their own strengths. If you play to theirs rather than yours, they are always going to come off better than you in the long run. This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

MH: You weighed in almost 5kg lighter for the second fight and were under 108kg for the first time since 2014. How did you adapt your training to come in so visibly leaner?

AJ: Ha, ha! You want me to give away my secrets? You’ve just got to be specific. Training is all about what you’re trying to achieve. To prepare for 12 rounds of boxing, it sounds obvious, but you’ve got to box, box, box. And that’s what we did.

There’s not much point boxing and then spending time in the swimming pool to build endurance, because all you’re doing is building swimming endurance. The same goes for boxing a little bit and then spending hours lifting weights, because that’s for weightlifters. The best boxing stamina work you can do is to hit the heavy bag or shadow box. Everything that involves boxing without getting injured is the best form of training.

It’s a simple thing that’s easy to overlook. If you want to get good at something, do that thing. Focus on it. We try to add this and that, strip it back. But you need to box more if you want to be in shape for boxing.

Joshua found success in stripping back his approach

MH: In what way did you change your nutrition? Is it true that Wladimir Klitschko advised you to reduce your salt intake?

AJ: I did cut out salt leading up to that fight. But the food was so bland! You don’t realise how much we depend on salts and sugars. When you remove them, you realise what the true taste of food is like. It had a real benefit, though, because it stripped my body of all the excess sugar and salt I didn’t need, and I managed to lose a shedload of weight.

Chicken and broccoli are tough when you can’t put any spice on them. Someone said to me that it’s not the chicken we like – it’s the spice and the sauces. That’s why I think vegetarians and vegans are onto something. We’re not meant to like chicken. They put the same sauces and spices on vegetables and get that taste and texture.

MH: What’s your diet like coming up to a weigh-in for a fight?

AJ: It’s pretty spot on. Weigh-in is usually about 2pm, so I will have had breakfast and lunch by then. Luckily, I don’t have to “make” weight, so I just continue my preparations like it’s another day. I don’t prepare for the scales; I just use it as an opportunity to showcase my work ethic and how hard I’ve been training.

MH: All boxers come in for criticism on social media. How do you handle negative comments or haters?