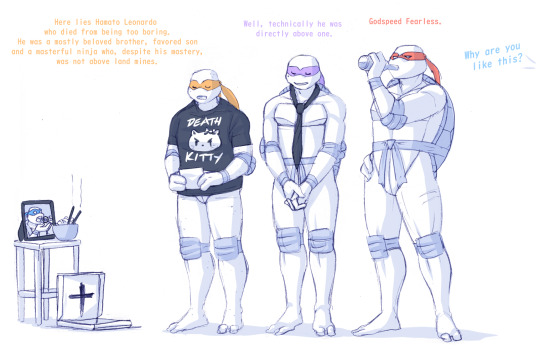

#this all came to be because I wanted to make a 'leonardo of the landmines' joke

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

LMAO YES

He didn’t let them sign up for Demolition Derby with the BattleShell

Retaliation:

#tmnt#tmnt 2003#this all came to be because I wanted to make a 'leonardo of the landmines' joke#and... it turned into an eulogy#why is raph drinking beer you ask? As a sign of disrespect#I live for Leonardo tormented eldest brother#addition#lol

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

INGMAR BERGMAN’S ‘AUTUMN SONATA’ “People like you are a menace”

© 2019 by James Clark

I can’t, for the life of me, regard Ingmar Bergman’s film, Autumn Sonata(1978), as the flat-out domestic clash others choose to believe. What is the real fascination and entry-point here, to me, is that the film’s protagonist, Eva, played by actress Liv Ullman, is made to look like a carbon copy of the actress, Ingrid Thulin, in the Bergman film, Winter Light (1963). Whereas Ullman generally holds forth as a flakey dreamboat, Thulin forever relishes looking and behaving scary. And, moreover, the latter’s performance, as an off again/ on again lover of a rural clergyman, looms very large in Autumn Sonata.Arguably the most contentious and demanding of all Bergman’s films, Winter Light needs to be carefully fathomed, if nonsensical soap opera is to be avoided here. Thulin’s Marta, in that 60’s puzzler, perseveres as a fatuous humanitarian infatuated by an angst-ridden atheist priest. The latter has come to detest her ugly body and her even more ugly attitude. But he is very fortunate that the sexton of the church (a retired, hunchback railway man, named Algot) is a far deeper student of spirit than he (which is to say, a far better acrobat)—quixotically larding his sense of Jesus as a misunderstood, sensualist mortal (mortal, period)—and, as such, a slow-dawning supplement of the so-called expert’s long-held, heretical orientation. It is this ironic eventuality of risk-taking which opens the door to Marta being still in the picture and now a beneficiary of a regime of that “juggling” of opposites so dear to the vision of this film series.

The return of the aura of Marta within the orbit of Eva effectively messes up the facile supposition that we are here to deal with the dynamics and possible salvation of a family. One other inspired touch, apropos of the elephant in the parlor, is the choice of career-long wayward Ullman’s adversary, namely, Hollywood star, Ingrid Bergman, a career-long, banner sentimentalist, in her swan song, as Eva’s mother—light years away from all her other pleasing roles confirming eternal feminine wisdom. As if to lend a hand in clarifying where these rather abstruse landmines lurk, the first scene ignores “timeless truths,” in order to broach something quite new. Eva is married to another clueless preacher, Viktor (no less), who idolizes her imaginative—Algot-like—zeal, and his is the sermon of the day. With Eva at her desk in the blurred distance, there is Viktor, just outside the study, addressing us, in close-up, with some good news, pertaining to her apparently significant, individual source of reflection, salient in its disinterestedness. (A preamble, to that singularity we’re supposedly to buy into by means of the acolyte/ guide, is Victor’s sense of seeming miraculousness in becoming her husband. This would constitute a sort of inversion of Jof and Marie, from the mother lode that is The Seventh Seal. It would also constitute this Norwegian backwater being a vaguely subversive agency.)

At that doorway, where we meet them, Viktor also provides a smattering of Eva’s rather cosmopolitan background. She had a several years’ relationship in Oslo with a medical doctor and had written “two small books” during that time, before cutting off the technician. (We should, on the basis of that sketch, recall the imaginative protagonist in Bergman’s film, Through a Glass Darkly[1959], who comes to grief with a husband/ doctor, loathing her failing to worship in the church that is rather bloody-minded science for the tone-deaf and feeble courage, and convincing her that she is schizophrenic and needing to be locked up in a mental hospital. In her being violated, she comes to regard God as a giant spider. As it happens, Ingrid’s role here, as Charlotte, a famous classical pianist, comes to show us her technique on the keyboard, which reveals one hand in action being like a flitting spider. Moreover, in the Ingrid vehicle, Gaslight [1944], she finds her run-of-the-mill-crook/ husband attempting to see herself insane, and ripe for suicide and a nice payday.) Eva’s next gig was as a journalist; and in that capacity she met Viktor at a bishop’s reception where she wouldn’t have to linger long—though seeing in Viktor a gentle front to make some progress.

On the day we meet them, he explains that he often pauses by her workshop/ study/ dining room to try to imagine how newish thoughts come about. Pulling out one of the “little books,” he tells us, “This is the first of her books. I like it so much. She has written, ‘One must learn to live. I practice every day. My biggest obstacle is that I don’t know who I am. I grope blindly. If anyone ever loves me as I am [which is to say, loves her vastly unusual and usually hated presence], I may dare at last to look at myself [to become a factor in a hitherto, totally, hostile jungle]. For me that possibility is fairly remote.’” Viktor reverts to his own statement, to confirm to us that the mild spouse looms, notwithstanding a strong loyalty, as part of the jungle which bedevils her seemingly placid home and militant planet. “I’d like to tell her just once that she is loved wholeheartedly, but I can’t say it in a way that she’d believe [she in fact not looking to him for accompanying her high-risk leaps]. I can’t find the words [he can’t find the daring].”

He leaves his post as Eva approaches us, folding a letter to Charlotte (of whom there has been not a word in seven years). Coming to his office, she’s of a mind to have Viktor read aloud what she’s now proposed for their partnership, with the one silent partner. (First, though, we hear from the active partner that she has learned, from a mutual friend, that Charlotte’s lover, a Renaissance man, Leonardo [no less], has died.) “Dearest, Mama, I know what a terrible blow this must be to you. [She and he actually knowing nothing of the sort.] I was wondering if you’d care to come to visit us for a few days or weeks. Please don’t say no, right away… We have a piano and you can practice all you want to. [A vaguely cavalier gambit.] It would make a change from a hotel. [Superstars don’t usually get kicked around like that.] …We’ll make a fuss over you and spoil you.” [The ambiguities of “fuss” and “spoil,” in play.]

For whatever reason Charlotte agrees to come, it is clear the fjord locale is not the attraction. On reaching Eva’s bailiwick, the visitor is most struck that her drive has aggravated her chronic back condition. “Well, here I am,” the communicator fails, a communicator who had failed to look at the letters mentioning that their four-year-old had drowned several years ago. (Don’t for a second imagine that this is a family reunion or any form of family. Both of the women are out for something transcending family. And both of them crash miserably.) Charlotte does feel obliged to say, “It’s beautiful here,” and promises to her daughter’s hope, “Indeed, I will” [stay a long time]. Getting down to business, Eva asks, “You’ll give me some lessons, won’t you?” Charlotte’s, “Yes,” could just as well mean, “That wasn’t what I came to do here.”

Eva, I think, when you take account of her daily “practice,” could well be using Charlotte’s disarray in order to challenge the long-term, almost forgotten, contempt she sees everywhere, but particularly in the mother who could and should be exposed as being far from the real deal. And what chased Charlotte out of the woodwork? The end of a gratifying liaison in an ancient villa, the loss of which prompting a revamp of her solicitousness? (She will mention, after the skirmish to come, “I am always homesick, but, moreover, I find it’s something else I am longing for…”)

The musical royalty inherent in Charlotte, after iterating that her back hurts (sign of a weak backbone?), dashes into a long account of being wonderful under the stress of Leonardo’s final days. (Travel does have a way of crowding out what you really should be attending to. Rather than shooting her geriatric face off, her agenda would be better met by listening and watching.) “I sat with him through his last day and night. He was in bad pain. They gave him shots every two hours. Now and then he cried because it hurt. He wasn’t afraid of dying.” This tug-of-war about grace might have been an avenue taking her and us a long way. Losing, as she carelessly does, such a field of well-being and ascendance might have put Charlotte seeing some playability about the hosts, a primer in a new solitude. Being an acrobat of high distinction in the mode of music does closely coincide with juggling as to others. Could she take that opportunity with Eva and Viktor? Did Leonardo open a door to her where there is much to be learned and enjoyed? (During the brawl to come, Charlotte reveals that her nothing of a set of parents—nothing but money—hurled her into a process of regarding nothing but the gratifications of brilliantly hitting the right notes.)

Eva’s moment to shine would be at the piano and its heretic arrangements. But her mother has tossed such a load of dismal screwballs at the outset as to shred her (truth to tell frail) reflective traction. (What looked, to her, at that sanctuary at the silent desk, being a go, nearly instantly becomes the ruin of all her rosy plans. The paragon of a range of sublimity puts foot to the floor a very common bilge of gossip pertaining to her friend’s cancer implicating the factor of plague, so omnipresent in the films of Bergman, where the functional so rapidly slips to the dysfunctional.) “The sun was blazing down and there were no awnings.” Then there were troubles securing a better room in the hospital. She opens the window at sunset (without any sharing of the beauty). “He said it wouldn’t be long…”—the kind of insert familiar from the world of Nicholas Ray. “The nurse said I should eat. But I wasn’t hungry… The smell was making me sick. Leonardo dozed off; then woke up and asked me to leave the room. He called the night nurse, and she came with a shot. A minute or two later, she came out and said Leonardo was dead… We had lived together for 13 years. And had never had an angry word. As often as I could, I went to see him at his villa near Naples. He was kind and thoughtful and happy about my success… One day, he gave me a long look and lovingly said, ‘This time next year I’ll be gone… but I’ll always be with you.’ It was sweet of him to say so, but he was apt to be rather theatrical… I can’t say I go around grieving. Of course he left a gap but it’s no good fretting… Do you think I’ve changed much?” “You’re just the same,” Eva tells her, having been seen, by quick cuts, overrun by Charlotte’s remarkable grossness.

The visitor/ technocrat eventually notices the disappointment and tears on her daughter’s face. “Did I say something wrong?” the star asks. Eva brushes it off as being excited and a bit tense. Tentative hugs break up to news of such a supposed vacuum here, specifically, activated by Eva’s church accompaniment and recitals. This prompts Charlotte to compare that virtual nothing with the five school concerts she gave in Los Angeles, each time seating 3000 children. “I played and talked with them. I was a huge success…” That unspoken provocation, now part of a new realization that her mother will always be a sterile, but volatile, brute, shifts the sophisticated hope into the shadows in order to posit a cheap assault of her own. With the fanfare, “There’s something I have to tell you,” Eva melodramatically discloses that her cerebral- palsy-victim-sister, Helena, whom Charlotte consigned to a clinic of the hopeless, years ago, to forget (later she will reason, “Why can’t she die?”), has for the past few years been living with the hosts. The doting mother had prefaced her annoyance with, “Some people are so naïve.” When Eva retorts, “You mean me?” the now feeling-besieged guest snarls, “If the shoe fits.” Not surprisingly, on meeting the one she hoped to never see again, she takes off her wristwatch, and, placing it on her daughter, tells her, “It was a gift from an admirer who said I was always late…”

A quick cut from this bemusing good deed finds Charlotte in her room devouring a cigarette and firing off the soliloquy, “Why do I feel like a fever? Why do I want to cry? I’m to be put to shame. That’s the idea. A guilty conscience. Always a guilty conscience. I was in such a hurry to get here. What was I expecting? What was I longing for so desperately?” Cut to the dining room where the hosts, putting out the best tableware, have become tentative, and in the case of Eva, pathological. “You should have seen her when I told her Lena was here! She actually managed a smile…” What she actually managed managed—along with the hostess who imagined taking the classy road—was to obliterate any traction toward disinterested discovery between them. Now tightened like snare drums, the duration of the visit becomes a fevered battle, testing us to see through shabby rhetoric (like the dead sermon of Tomas, in Winter Light, and the dead childishness of Isak, in Fanny and Alexander).

We’ll cover this death march in two ways: a brief unpleasantness which probably never should have seen the light of day; and, a more extensive survey, of the textures of civilized hate. “I’ll cut my visit short,” the world traveler tells herself. “Then I’ll go to Africa, as I originally planned” [hoping to find in exotica the coverage she hardly dares to admit she lacks]. At any rate, she is ruthless (not the same thing as resolute) in her makeover. (“I held her [Helena’s] face and felt the disease twitching at her throat muscles.”) What needs to be recognized here, for Bergman’s work, is that the convention of family, for all its pragmatism and caring, is grossly overrated and stands essentially as a means of instinctively crushing serious lucidity, which is to say, serious love. Eva is embarrassed in her no longer seeing any point of contributing her musicianship in Charlotte’s presence, while being forced to suffer it, anyway; that night, the hostess invades the top dog and rains a dismal hurricane upon her mother, for having been a very poor instance of the form. The visitor leaves in the morning, never to be seen again.

However unforthcoming the interplay proves to be, it’s a gold mine treating of endeavor and its quicksands. With Charlotte dressing like a Mayan goddess for the Nordic 4 pm dinner, and handed, by a phone call from her agent, a small fortune for a week’s labor, she’s ready for what’s left of the day. Before she has surfaced, however, the hospitality-2 slips into a register often heard in the films of Nicholas Ray. Eva blurts out, “It’s like a ghost falling on top of you… Do you think I’m an adult?” Viktor tells her, “I guess being an adult is being able to handle your dreams and hopes, not longing for things… Maybe you stop being surprised.” Eva adds, “You look so sensible with your old pipe. You’re very adult.” (Viktor being a cipher; but her rapid decline being chilling.) After the end of that premature dinner, there is, by the protagonist’s one and only fan (unaware that the recital is now a bad idea), his urging her to what in fact is an arrangement of a Chopin prelude being shot forward a century to come forth as discrete notes reaching for others of that kind and taking the pulse of the infrastructure of sound itself. “But you wanted your mother to hear you play,” the innocent calls out. A nervous and unnerved performance ensues, with cuts to Charlotte, clearly unimpressed. The latter’s formulated politeness—“Eva, my darling. I was just so moved—adds to Eva’s annoyance. “Did you like it?”/ “I liked you.” The expert adds, “We each have our own.” The hostess’, “Exactly,” does not rise to diplomacy. Nor does her insistence to have Charlotte deliver her own rendition. Not only does the guest provide a powerfully professional effort; but she adds a conceptual commentary, which comes to bear as an exploding of the revolutionary’s emotionality. “Chopin was emotional but not sentimental. Feeling is very far from sentimentality. The Prelude tells of pain, not reverie. You have to be calm, clear and even harsh. Take the first bars, now. It hurts but he doesn’t show it. Then a short relief. But it evaporates immediately, and the pain is the same. Total restraint the whole time. Chopin was proud, passionate, tormented and very manly. He wasn’t a sentimental old woman. The Prelude must sound almost ugly. It is never ingratiating. It would sound wrong. You have to battle your way through it and emerge triumphant.”

Eva gives credit to Charlotte’s cogency, particularly since it is, appearances notwithstanding, surprisingly close to her own cogency. Crowning her lecture, the leader of thousands intimates, “For 45 years I’ve worked at these terrible preludes. They still contain a lot of secrets…” (Secrets, in fact, which Eva, the fragile rebel, had broached at her hermetic writing table, and also, perhaps, in face of the sentimental accompaniment of the popular music of her era. Thereby, not only the rather heroic involvement with Helena, but the shrine she has maintained in her dead son’s bedroom, being for her a way, “to let my thoughts wonder” [also a shock to Charlotte], implies, despite quixotic concomitants, a concern for some kind of holistic action, which her present guest seems intent to avoid at all costs. During the cattiness when setting the table, Eva emphasizes her upbringing in the style of “beautiful words,” which she equates with a large measure of phoniness (and explicitly nails hapless Viktor—he’ll tell the inoperative mother-in-law that Eva’s tenure here involves never a moment of love [in fact, her experience in total never entailing love]—for his being one such weakling when trying to be affectionate). And yet, at the shrine for the boy, she runs with “beautiful words,” hoping to mesmerize the multi-faceted celebrity along a course of rather facile “secrets.” “All I have to do is concentrate and he [toddler, Eric]is there. Sometimes, as I’m falling asleep, I can feel him breathing in my face… It’s a world of liberated feelings… There must be countless realities, not only the reality we perceive with our dull senses… It’s just fear and priggishness to believe in limits…” Eva looks to the Mom who is not a Mom, to corroborate these findings. Charlotte, for all her scandal, is far too savvy to buy into that scenario.

And that rebuff, in the vernacular of another era of confusion—Viktor telling Charlotte, “She [Eva, the myopic seer] got lazy, gazing at the play of light over the mountains and fjords”—goes viral soon after the clichés of pleasant dreams are done. Just before that, however, a little pothole springs up, when Charlotte (never straying from the forum having made her a rich goddess) brings up the loveless marriage. “If only you’d leave people alone!” Eva snaps, before assuring that she’s cool. The cool one fumes in the stairwell, while the pragmatist counts her recent inheritance and fantasizes giving the hosts a better car. “It’ll cheer them up.” Where things stand now—livid that she’ll never be part of a majority—nothing could cheer her up. Hearing Charlotte having a nightmare provides a pretext to attack. The aftermath of such an event being a prelude, for Bergman’s work, to cling to security, there is the mother, who isn’t a mother, fishing (as her daughter had gone fishing) for solicitude: “You do like me, don’t you?” / “You are my mother,” comes back, as if she’d pulled a handgun. Ready to be devastating, the one who loves no one plays a game of love. “Do you like me?”/ The rapid response is, “I love you. I broke off my career to stay at home with you and Papa.” Eva adds the cutting complement, “Your back prevented you from practicing six hours a day. Your playing got worse and so did your reviews. Have you forgotten it? I don’t know which I hated more, when you were at home or when you were on tour. I realize now you made life hell for Papa and me.”

She’ll go on to skewer the guest for being unfaithful to her father, amused by the attempts to maintain that everyone in the loop was cool. She’ll go on all night in that domestic vein, while the concise drama comprises her caring not a whit about that matter (while confronting her impotence as a thinker and cowardly laziness as a human being, along with large amounts of wine, put her in a temporary perspective of such madness). Of course, some sanity would prevail—one of Eva’s eyes fastened over the glass, her eye distorted—as she cries out, “I’m so confused! I thought I was grown up and could look clearly at you and me. Now it’s all one big muddle!” But when Charlotte attempts to state the obvious, “You’re exaggerating,” she’s met with, “You’re interrupting!” After more ridiculous momentum, the interrupted (largely self-interrupted) investigator asks, “What am I to say?” The nasty drunk replies, “Defend yourself!” [the ugly brawl, in Sawdust and Tinsel, 1953, putting in a brief visit]. To which the sort of Merry Widow asks, “Is it worthwhile?” Eva relives a time when Helena was hale, if not hearty, and Charlotte and Leonardo came by the homestead for a visit. The celebrity soon hopped off to Switzerland to prepare more fabulousness, and Leonardo was confronted by an adolescent Helena being infatuated by him. The less than Renaissance Man rudely bolts to Alpine power, disturbing the young girl to a point of her condition flaring up. This memory becomes an indictment going so far as to Eva’s accusing her mother that her poor behavior was the cause of the sister’s being a cripple. (“He left on the last plane…” [a touch of Casablanca melodrama].) “There’s only one truth and one lie. You’ve set up a sort of discount system with life, but one day you’ll see that your argument is one-sided. You’ll see you’re harboring a guilt, just like everyone else…” During the long night, Charlotte had had her own confusion and tears, in addition to needing to lie on the firm floor to offset a lack of backbone. Eva had spent most of the night in a chair which becomes an ironic throne, to Charlotte’s being a supplicant. The last word really registering, as the night dribbles down to clichés, like an Ingrid Bergman movie, is the visitor on the way out: “What guilt?”

Eva takes a walk in a graveyard by the fjord, untrammeled by the bilious self-expression that shot down the proposals of the thinkers of the day before. It’s getting dark, and the mystic has an agenda—making dinner for Helena and Viktor. But the rather alarming multi-tasker gives us a break. Though being surrounded by the dead, she commences a dialogue (frequently complemented by cuts to Charlotte and her agent, in a first-class train coach, on the matter of “something else I’m longing for…” as they flee from a cursed detour). “Are you stroking my cheek? Are you whispering in my ear? Are you with me now? We’ll never leave each other.” [The artist/ profit-center asks her neat-as-a-pin associate, “What would I do without you?” She’s suddenly troubled and looks into the darkness outside, her reflection leaving her cold.]

Once again, Viktor addresses us about his wife’s singularity: “She’s in such distress since Charlotte left so suddenly. She has not been able to sleep. She says she drove her mother away and can never forgive herself.” Once again, he’s to read out loud a letter to Charlotte, which can’t be seen as annoying. “Dear, Mama, I realize that I wronged you. I met you with demands instead of affection. I tormented you with an old hatred that’s no longer real. I want to ask for your forgiveness. I don’t know if this letter will reach you. I don’t even know if you will read it. Maybe everything is too late. But I hope all the same that my effort will not be in vain. There is a kind of mercy, after all. [It’s interplay by her has not been well engaged by the puppy-love that she’s reached.] I mean the enormous opportunity of getting to take care of each other. I will never let you vanish out of my life again. I’m going to persist. I won’t give up, even if it is too late. I don’t think it is too late.” [“Beautiful words, going nowhere.”] Though Bergman would have regarded the films of Jacques Demy as an abomination, the latter helmsman, a student of Robert Bresson, does, in his musical fantasy, Donkey Skin (1970), provide an oracle right out of our guide here, to wit, “Life is not as easy as you think.”

We’ve been challenged, by Autumn Sonata, to investigate a musical cosmos both elegant and vicious, both solo and infinite. (The backdrop of the initial credits presents us with a wildfire [perhaps including blood].) Each of the protagonists readily sees through the other’s shabbiness. Charlotte refers, with much validity, to her daughter’s being a “crybaby.” Eva, finding her mother a lot like her long ago, Oslo boyfriend, describes Charlotte as, “People like you are a menace. You should be locked away and rendered harmless.” While Eva dabbles with, “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida,” Charlotte, far more self-critical and sophisticated, notes, “Leonardo [in a seer role] once said, ‘A sense of reality is a matter of talent. Most people lack that talent and maybe it’s just as well.’” She asks if Eva knows what he meant. Recalling her mantra, “One must learn to live. I practice every day…” she comes to the matter differently. Talent and practice. The colloquium being a bust. But not a waste of time.

0 notes

Photo

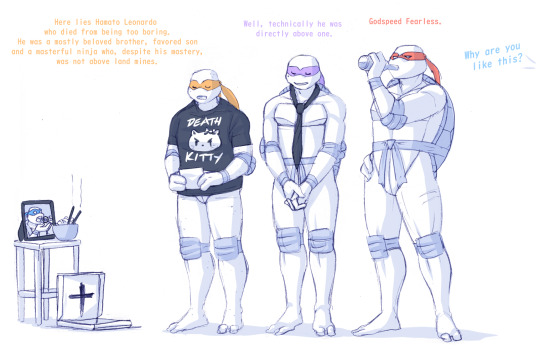

He didn’t let them sign up for Demolition Derby with the BattleShell

Retaliation:

#tmnt#tmnt 2003#michelangelo#donatello#raphael#leonardo#master splinter#this all came to be because I wanted to make a 'leonardo of the landmines' joke#and... it turned into an eulogy#why is raph drinking beer you ask? As a sign of disrespect#I live for Leonardo tormented eldest brother

6K notes

·

View notes