#these two quotes always come to mind when I try to explain my linguistic difficulties and ironically I usually find myself in Naoko's shoes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Raven King by Maggie Stiefvater (ch 37) // Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami (ch 2)

(Quote text under read more)

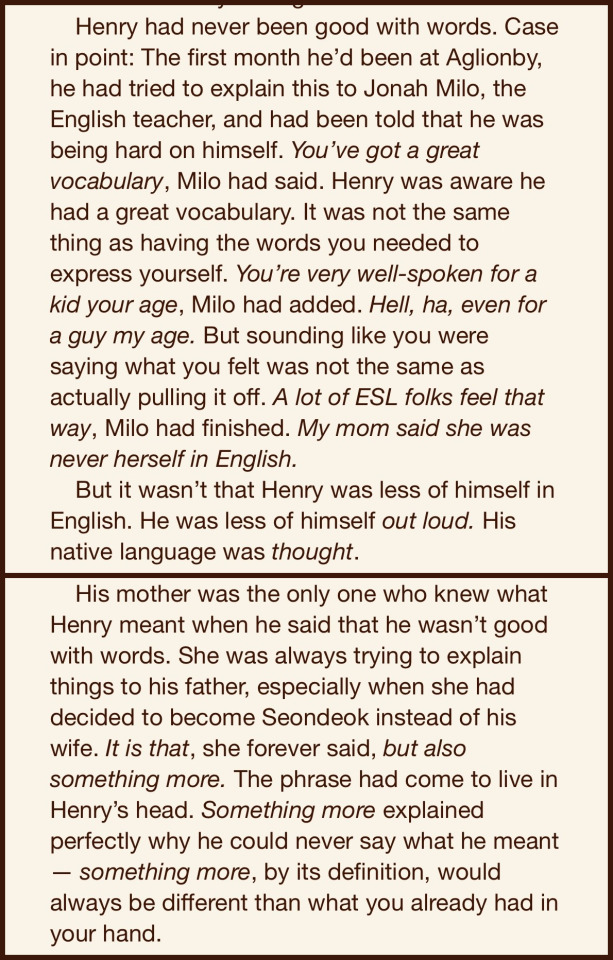

Henry had never been good with words. Case in point: The first month he'd been at Aglionby, he had tried to explain this to Jonah Milo, the English teacher, and had been told that he was being hard on himself. You've got a great vocabulary, Milo had said. Henry was aware he had a great vocabulary. It was not the same thing as having the words you needed to express yourself. You're very well-spoken for a kid your age, Mino had added. Hell, ha, even for a guy my age. But sounding like you were saying what you felt was not the same as actually pulling it off. A lot of ESL folks feel that way, Milo had finished. My mom said she was never herself in English. But it wasn't that Henry was less of himself in English. He was less of himself out loud. His native language was thought.

His mother was the only one who knew what Henry meant when he said that he wasn't good with words. She was always trying to explain things to his father, especially when she had decided to become Seondeok instead of his wife. It is that, she forever said, but also something more. The phrase had come to live in Henry's head. Something more explained perfectly why he could never say what he meant — something more, by its definition, would always be different than what you already had in your hand.

— — —

"I can never say what I want to say," continued Naoko. "It's been like this for a while now. I try to say something, but all I get are the wrong words - the wrong words or the exact opposite words from what I mean. I try to correct myself, and that only makes it worse. I lose track of what I was trying to say to begin with. It's like I'm split in two and playing tag with myself. One half is chasing the other half around this big, fat post. The other me has the right words, but this me can't catch her." She raised her face and looked into my eyes. "Does this make any sense to you?" "Everybody feels like that to some extent," I said. "They're trying to express themselves and it bothers then when they can't get it right." Naoko looked disappointed with my answer. "No, that's not it either," she said without further explanation.

#Haruki Murakami#Norwegian Wood#The Raven King#maggie stiefvater#I came across a post the other day talking about difficulties with speech and neurodivergency#specifically the fact that speech with one's mouth and with ASL and typed/written out is all effectively the same#including within the context of going nonverbal#and that going nonverbal and speech loss or selective mutism are not the same thing even if people online often confuse the them#I don't know... what exactly my issue is -- well it's several issues that exacerbate each other but point being#these two quotes always come to mind when I try to explain my linguistic difficulties and ironically I usually find myself in Naoko's shoes#Meanwhile the one time I tried to talk to my mother about it she said “But you're so eloquent!”#I've lost track of where I was going here...#tldr language hard

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Happiness Hypothesis: Chapter 1, “The Divided Self”

[NOTE: I am reading this book for a book club at my work, and I wanted to take notes so it would be easier to discuss. I don’t really recommend reading this post if you haven’t already read the book! My summary is long enough that you might as well just go read the original thing. Haidt writes much better than I do. I’m just doing this because note-taking helps me remember things.]

The theme of this chapter was: the self contains multiple parts, which are often at odds with each other.

A relevant quote from ancient literature:

St. Paul, Galatians 5:171: For what the flesh desires is opposed to the Spirit, and what the Spirit desires is opposed to the flesh; for these are opposed to each other, to prevent you from doing what you want.

In order to explain the divided self, Haidt introduces the metaphor of the elephant and the rider (which also appears in his book The Righteous Mind). You can think of the mind as containing two parts, an elephant and a rider. The elephant represents emotions, deep biological urges, and automatic mental processes. The rider represents reason, logic, and conscious thought. The point of the metaphor is that the elephant is much larger, and is basically in control. The rider can try to control the elephant; it can give directions, and sometimes those directions will even be followed. But if the elephant really wants to go in a particular direction, there’s not much the rider can to do stop it.

Comparing the divided self to a rider and an animal also has precedents in ancient literature, and Haidt gives a couple of quotes:

Buddha: In days gone by this mind of mine used to stray wherever selfish desire or lust or pleasure would lead it. Today this mind does not stray and is under the harmony of control, even as a wild elephant is controlled by the trainer.

Plato described the self as a chariot, with two horses and a driver holding the reins: The horse that is on the right, or nobler, side is upright in frame and well-jointed, with a high neck and a regal nose; ... he is a lover of honor with modesty and self-control; companion to true glory, he needs no whip, and is guided by verbal commands alone. The other horse is a crooked great jumble of limbs ... companion to wild boasts and indecency, he is shaggy around the ears -- deaf as a post -- and just barely yields to horse-whip and goad combined.

Haidt also mentions Freud as a proponent of the divided self.

Then he describes four ways in which the self is divided.

Mind vs. Body

Many people have described the penis of having a mind of its own.

The autonomic nervous system, which governs many bodily functions, exists outside of conscious control.

There’s a whole separate “gut brain” containing over 100 million neurons, which controls digestion and operates largely independently of the real brain.

Left vs. Right

This is referring to the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

The left hemisphere does language and analytical tasks. The right hemisphere is better at spatial reasoning. (Though Haidt is quick to point out that the idea of scientists being “left-brained” and artists being “right-brained” is oversimplified.)

Haidt talks about split-brain patients (people whose left and right brains can’t communicate with each other). The left hemisphere processes information from the right visual field, and vice versa. So the scientists took some split-brained patients, and showed them a picture of a hat on the right side of their visual field. When asked what they saw, they were able to respond (since the left, verbal hemisphere was the one that got the information). When the picture was shown on the left side, the patients would say they saw nothing, but their left hand would still be able to point at the correct object.

The funny thing is, if you show the right hemisphere some information that causes it to act in a certain way, the left hemisphere will generate an explanation for the action, even though it has no idea what the real reason is. So, like, if you show the right hemisphere the word “walk”, the patient might get up and start walking. And if you ask them why they got up, they might say something like “I’m going to get a Coke”.

Haidt thinks this is important, because it means there’s a part of the brain that’s totally willing to generate explanations of things you do, even though it has no idea why you actually did it.

Actually, I should just quote him directly about this last bit:

These dramatic splits of the mind are caused by rare splits of the brain. Normal people are not split-brained. Yet the split-brain studies were important in psychology because they showed in such an eerie way that the mind is a confederation of modules capable of working independently and even, sometimes, at cross-purposes. Split-brain studies are important for this book because they show in such a dramatic way that one of these modules is good at inventing convincing explanations for your behavior, even when it has no knowledge of the causes of your behavior.

Haidt equates this “convincing explanation” module with the rider in the rider/elephant metaphor. The elephant takes some action, and then the rider (without necessarily knowing why the elephant did it) comes up with an explanation.

New vs. Old

New parts of the brain have been added over the course of our evolutionary history.

The oldest parts are in the back and the newest parts are in the front.

The limbic system is an older part of the brain, which controls our “animal urges” (sex, aggression, hunger).

The frontal cortex is a newer part of the brain which contains our critical faculties.

But emotion and reason are not cleanly divided between these two parts of the brain. Actually, a great deal of our emotional functions reside in the orbitofrontal cortex, which is part of the frontal cortex. So it’s not “newer, human reason” and “older, animal urges and emotions”. It’s more like “older animal urges” and “newer human reason and emotions”.

Also, we need our emotions in order to function in life. When the orbitofrontal cortex is damaged, you don’t get a bunch of perfectly logical superhumans, capable of overcoming problems without interference from emotions. Instead, you get people who are perfectly able to reason, but who have great difficulty making decisions, since they have no emotions to guide them towards one choice or another.

Haidt emphasizes that it’s not the rider (reason) controlling the elephant (which includes the emotions of the orbitofrontal cortex). The rider and the elephant have to work together to get anything accomplished. But it’s the elephant that’s doing most of the work.

Controlled vs. Automatic

The mind contains two processing systems, controlled and automatic (I’m guessing these relate to Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2).

Haidt says that “most mental processes happen automatically, without the need for conscious attention or control”. These automatic processes also tend to be unconscious.

There are also controlled processes, “the kind of thinking that takes some effort, that proceeds in steps and that always plays out on the center stage of consciousness”.

We can only have one controlled process running at a time, whereas we can have tons of automatic processes running in parallel.

So what is the relationship between controlled and automatic processes?

Automatic processes have existed throughout our evolutionary history, while controlled processes require language and are therefore quite new. So we’re on “Rider version 1.0″ (controlled processes are the rider, automatic processes are the elephant) and elephant version 1000 or whatever. That’s why “there are still a lot of bugs in the reasoning and planning programs” but the automatic processes are nearly perfect. And that’s why it’s easy to build an AI that plays games and solves logic puzzles as well as humans, but much harder to build one that can see or walk as well as we can.

I’m just going to quote the next paragraph because it’s hard to summarize:

Evolution never looks ahead. It can’t plan the best way to travel from point A to point B. Instead, small changes to existing forms arise (by genetic mutation), and spread within a population to the extent that they help organisms respond more effectively to current conditions. When language evolved, the human brain was not reengineered to hand over the reins of power to the rider (conscious verbal thinking). Things were already working pretty well, and linguistic ability spread to the extent that it helped the elephant do something important in a better way. The rider evolved to serve the elephant. But whatever its origin, once we had it, language was a powerful tool that could be used in new ways, and evolution then selected those individuals who got the best use out of it.

One function of language is that it helps to free us from the behaviorist stimulus-response stuff that Skinner and Pavlov studied. Instead of being complete slaves to immediate temptation, we’re able to think about the long-term consequences of our actions. But of course, we’re still somewhat susceptible to behaviorist principles.

So the rider isn’t king, or boss, or in charge of the elephant. The rider can be better understood as an advisor to the elephant, providing guidance but not any actual control over what the elephant does.

Haidt writes:

The elephant and the rider each have their own intelligence, and when they work together well they enable the unique brilliance of human beings. But they don’t always work together well.

Then he gives three cases where they don’t.

Failures of Self Control

Haidt gives the example of the marshmallow experiment. He points out that the kids who did best in the marshmallow experiment were the ones who were able to distract themselves from thinking about the marshmallow.

This has the following lesson: it’s hard to control yourself via willpower alone (since the controlled processes will get tired, and the automatic processes will keep on going). So instead of pitting willpower against “stimulus control” (that is, environmental stimuli controlling what you do), it’s better to either change your environment (so you’re not confronted with the temptation), or change your automatic response to that stimulus (apparently Buddhists overcame carnal temptations by thinking about the body as a rotting corpse).

Mental Intrusions

This section was about the difficulty of “not thinking about a white bear” (or whatever else you try not to think about). According to Haidt, your conscious mind tries not to think about a white bear. Meanwhile, your automatic processes continually check in to ask “am I thinking about a white bear?” This makes you work even harder to suppress the thought, which makes you check in even more, which makes the white bear even harder to stop thinking about.

Haidt says this is where a lot of obsessive thoughts come from. A scary or shameful thought shows up in your mind, and you try to suppress it, which only leads to thinking about it more.

The Difficulty of Winning an Argument

Here, Haidt talks about his own research. He gives people a moral situation (in this case, a tale of incest between a brother and sister) and asks people whether it’s moral. People usually say “no”, but they have a hard time justifying why.

Haidt says this is another case (like in the split-brain patients) where one part of the mind has made a decision, and the rider tries to justify it without knowing why the decision was made. Haidt says:

In moral arguments, the rider goes beyond being just an advisor to the elephant; he becomes a lawyer, fighting in the court of public opinion to persuade others of the elephant’s point of view.

It’s worth pasting Haidt’s conclusion in full:

This, then, is our situation, lamented by St. Paul, Buddha, Ovid, and so many others. Our minds are loose confederations of parts, but we identify with and pay too much attention to one part: conscious verbal thinking. We are like the proverbial drunken man looking for his car keys under the street light. (”Did you drop them here?” asks the cop. “No” says the man, “I dropped them back there in the alley, but the light is better over here.”) Because we can see only one little corner of the mind’s vast operation, we are surprised when urges, wishes, and temptations emerge, seemingly from nowhere. We make pronouncements, vows, and resolutions, and then are surprised by our own powerlessness to carry them out. We sometimes fall into the view that we are fighting with our unconscious, our id, or our animal self. But really we are the whole thing. We are the rider, and we are the elephant. Both have their strengths and special skills.

So I guess he’s concluding that, in the light of modern science, the ancient wisdom is true. But it’s only a cause for concern if we identify too strongly with the rational parts of our minds.

1 note

·

View note