#there is probably a discussion about femininity to be had here but i'm not qualified enough to do that

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The fact that this page made me nearly tear up speaks of the level of character writing of Berserk

Farnese went from sadistically enjoying making people under herself suffer to feel a shred of power in her life, to panicking and rushing to protect the most vulnerable person that could be entrusted in her care, not for herself but because Casca needs to be cared for. And you get to see the evolution, what makes her question herself and the root of her beliefs, the guilt and sense of worthlessness that she carries with her and desperately wants to overcome.

What a wonderful character :)

#berserk#farnese de vandimion#how do you write meta about berserk when it has been dissected to its atomic structure for the past 30 years#i feel woefully inadequate#i just wanted to share this moment i felt#admittedly i always related to farnese#not really the sadistic part but the part where she realizes she's a burden not good for anything#which makes her desire to improve herself all the more touching#i also find interesting that her character development goes from being aggressive and stubborn to being meeker#on the surface of course#because farnese used to be aggressive to cover up her lack of spine with authority figures#while her quieter demeanor coincides with her becoming braver#there is probably a discussion about femininity to be had here but i'm not qualified enough to do that

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

mutuals only! i don't want this to spin out of control. okay here goes my first attempt at a gender/sexuality take, please tell me what you think

memes like these that celebrate being attracted to androgyny (used loosely, both seem pretty feminine to me) feel like they're still enforcing a gender binary. instead of admitting to some kind of pansexuality and letting non-binary folk feel included, it feels like it's saying "haha i love butch women girls and femboy man guys".

introspection that came to me after proofreading the above: am i asking too much? surely there may be bisexual people who are into gnc presentations of binary genders and not into non-binary folks, but i don't know if that's a thing that exists or a denial because of what kinds of gender non-conformity our societies allow into the mainstream. what i'm saying is i don't want to force anyone to say they're attracted to a group they're not attracted to, but that it seems potentially sus they're drawing a line around it.

introspection²: i think this is just a bisexual/pansexual/omnisexual discussion that's probably been had thousands of times, and i have never read on the subject so maybe i should do that before saying more about it. also i'm not into men so i'm not really qualified to talk about this probably

hmm. i should write down my thought process more often, this was fun. thoughts? (again, i discourage reblogs from non-mutuals, i don't want this shitty take to be taken out of its context: a random thought i had after waking up. if you're nice and really want to interact you may use comments)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, so I wonder if the problem here has less to do with translating the register of the speaker to something more natural for the target audience than with the fact that they used わ specifically.

If this were just an everyday interview on something like "What do you think of this tourist spot?" that has nothing to do with gender or differences in cultural norms in Aus vs. Japan, then I think that masculinizing her Japanese dub would probably draw unnecessary attention to her speech for TV viewers who are probably just expecting to learn how much foreigners love this one tourist spot in Japan. And I think you'd agree--you probably wouldn't have even reacted if they had made her speech a little more feminine but more neutral in other ways, like using 私 or ます・です (although that seems a little unnatural for a TV interview, and then you'd just be thinking about formality rather than gender).

I think the real issue is that... most Japanese women nowadays don't use わ. If a Japanese woman were stopped on the street for a similar interview, I highly doubt they would use わ, and of course they would never add わ in for any subbing of their dialogue.

When I was first reading this post, my first thought was about how I was watching my partner play dubbed Uncharted. It's not a series I'm especially familiar with, but when the female character came on and was speaking in わ and の all over the place, my first thought was... "She would not say that."

I mentioned this to my partner (who is not a translator but is a huge movie buff), and he mentioned that Uncharted in particular is going for a nostalgic, Hollywood style of movie, and the dubs in that case were mimicking the translation style of films in the 80s, which in a lot of ways defined Japanese people's expectations for Hollywood movies. As a result, I think those translation styles have stuck around because they're so entwined with the sense of "Hollywood movie", although that's not to say that things shouldn't be reevaluated and changed (or maybe even are currently in the midst of changing).

In fact, I kind of wonder if the use of わ nowadays has more in common with the classic Hollywood, Mid-Atlantic accent, which was really more affectation than actual dialect. Not to say that わ is also similarly constructed--it actually appears to have a long history beginning with school girls in the Meiji period using it maybe even as a form of mild rebellion (a more in-depth paper here that looks really intriguing). That image has obviously changed as it became widespread and more established, up until the current day where it would be an unusual way for modern women to talk, for whatever reason.

I feel like there could be a lot of issues coming to a head here that I'm not necessarily qualified to discuss... Like, is there a large overlap in audiovisual translators for Hollywood movies and Japanese news shows? Are there style guides keeping translators in line with rigid gender roles that perhaps need to be reevaluated? Do Japanese people expect Westerners to speak like Hollywood stars? Is there a larger tolerance for exaggeration in Japanese entertainment (think anime and kabuki) where Westerners expect more authenticity and realism? Is there a sort of shame associated with exaggerated feminism that we might not find in men's speech?

But in my opinion (as a non-native Japanese speaker), while I think わ may have an understandable place in media translation (or even native Japanese media), I do not think it had a place in that interview translation. It sounds like that was a neutrally casual Australian phrase that was not translated into what would be an equally neutral phrase for a Japanese woman, but instead added an unnecessary element of femininity.

I’ve been having trouble putting this idea into words so you’ll have to bear with me, but I was struck when I saw a Japanese news program interviewing foreign tourists in Japan, and some australian women were dubbed over with a stereotypically feminine speech register (lots of のs and わs), and my first thought was “they weren’t speaking that femininely in english”.

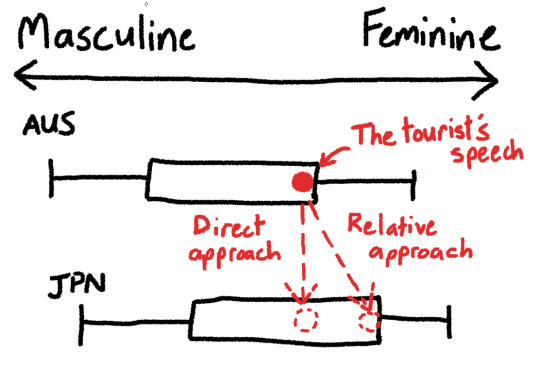

A friend of mine from the UK recently mentioned that he noticed that australia has a generally more masculine culture than england - he felt that everyone is a bit more masculine here, including women. This kind of confirmed to me that my impressions of the dubbing were right - the tourists were speaking in a relatively (internationally) more masculine way. Yet their dub made them sound so much more feminine.

It made me wonder. When translating something, do you translate the manner of speaking “directly”, or “relatively” in terms of cultural norms? Maybe this graph will help me explain the question.

A direct appoach in this case might appear to a Japanese person to result in an unexpectedly masculine register, but preserves how the speaker's cultural upbringing has influenced their speech.

The news program translators chose the relative approach - I think I would prefer the direct approach. I think I prefer it because I believe translation should be a rewriting of the original utterance as if the speaker was originally speaking the target language, and the direct approach compliments that way of thinking the best.

Actually now that I type that, I’m second guessing myself. Does it? It does, if for the purposes of the “rewrite it as if they spoke japanese” thought experiment, we suppose the speaker magically learned japanese seconds before making the utterance, but what if we suppose the speaker magically grew up learning japanese - then maybe they would conform to the relative cultural values. But also, maybe they would never have said such a thing in the first place - their original utterance was informed by their upbringing and cultural values, so how could you possibly know what they would have said if they had known japanese from birth? Maybe my initial instinct was right after all?

If you work in translation, I’m very interested to hear if you have come across this problem and how you deal with it 🙏

Further reading: I think this question also ties into this problem I’ve been struggling to answer for a while.

#translation#japanese#jimmy-diphthong#わ#This was such an exciting thought to stumble upon in my 5 seconds of tumblr today#and led to some really interesting discussions with my partner#I'm very curious to hear what kind of show it was used for#I'm guessing it's a fluff piece#And I don't always think those shows have the motive of showing authentic foreigners#both in who they choose to show and what responses they'll pick to broadcast from a whole reel#Also I'm really curious now about what style guides those shows may have for translators#And I wish I knew more E>J audiovisual translators to ask!!

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

i’m not sure if you do writing advice and if you don’t, feel free to ignore this! i was wondering how do you come up with such beautiful metaphors/descriptions in your writing? and are there any authors that are good examples of how to create new + striking ones? i struggle with finding new ways to describe things and i fear it’s making my writing boring :(

hi!! firstly, thank you so much for the compliment, it's incredibly kind. secondly, if i'm not mistaken you might have sent me a very similar question some months ago, and i totally forgot until now because i started to answer, draft it, then never remembered to finish it. if that was you i'm so sorry (and if it wasn’t you, i’m still very sorry to the person whose question i never answered)!! i'm not sure i ever feel entirely qualified to give writing advice, and please don’t think your writing is “boring” because it doesn’t fall into a certain style. i fully admit that i lean heavily on metaphor (which is probably obvious give you came to me with the question), but i tend to get really tired of this and wish i could write more pointed, startling prose than manages to impart emphasis without excessive description or “floweriness” (the most widely known author i can think of to point to might be chuck palahniuk, but on tumblr i also think abby aka @exalibur manages this beautifully). we are always hardest on ourselves, and the grass always looks greener on the other side of the stylistic hill.

ocean vuong discusses metaphor in particular better than i ever could, and there’s some reposts of stories he made on the subject here. i also think heather o'neill would be a fantastic person to look at for metaphor, particular her latest book when we lost our heads (albeit possibly my fave modern book is the lonely hearts hotel, if you read this please come scream to me about it). i pulled a couple quotes of o’neills from the former to use as example, which also fall in line with what vuong outlines:

The mansion was surrounded by a thick bed of beautifully kept pink roses. They were like ballerinas taking a break and sitting down in their tutus. darling. delightful. feminine. and with context, the home of a girl who would put sofia coppola’s marie antoinette moodboard to shame: precious, precocious, and doll-like. She found the violin, took it out of the case, and tried playing a note on it. It sounded like a black cat who was on the gallows confessing to all the bad luck it had caused. this character refused to play piano because she found every sound it made too happy, and didn’t feel it ‘matched her soul,’ which is why she would eventually try the violin. for a girl who would inadvertently murder someone, and spend much of her life wearing black and writing startling erotica, it’s also entirely on-theme. there’s obviously a lot of ways one could describe roses or the sound of a violin, but each fits perfectly into the respective character. if in the first quote the roses has been described as heavy red roses bowing reluctantly under the weight of a snowdrift like angry russian courtiers, you’re going to get a very different impression of the moment. as with the sound of the violin, if it has been described as a lonesome widow calling to her drowned lover from the pier, it’s going to completely alter the reader’s perception. so while these devices can create beautiful things to read in isolation, the most impactful ones are about more than saying something in a creative way: they add to the desired ambiance!

i know none of that is particularly instructive as to how i or others come up with descriptions, but i think that’s going to be very individual to the person! i personally like to think of it as the association game. i’d like to say it’s something more sophisticated than that, but a lot of the time it really does some down to just pausing for a moment and running along an evolution of images: the roses are red. what other physical objects are red? what emotions do we associate with red? what acts are those emotions elicited by? what sensations do we experience in those actions? there’s no right or wrong way to come up with your descriptive text, but don’t be afraid to take continual leaps not only forward, but backwards and sideways until you find something you like. even if you struggle to feel like you’re not being ‘original’ in the comparisons you’re drawing, there’s always ways to make something more ‘obvious’ less cliche. want to describe the colour red but can only think of roses? that’s okay! just rip it up a bit. turn it to sit on its side. think of a way to make it new. apply the notion of trying to impart something in your metaphor: where can a rose be seen, in what context can they be given or seen? instead of saying her lips were red as roses, there’s something like her lips were the red of a rose you’d find abandoned at the stage door, leaning its forgotten head across the last stoop. finally, it’s overstated (and you probably already know this given how you framed the question), but it also can’t be said enough: reading is your friend! while i definitely recommend the authors i mentioned above (or catherynne m valente, or janet fitch, or i remember reading how much of these hills is gold by c. pam zhang in the summer and thinking there was a gorgeous command of language), i think reading of any kind is going to give you a benefit. it’s just stretching the creative muscle, taking in new phrases, words, and ways to apply them. if you’re feeling mentally a bit bogged up, you could even listen to some spoken word poetry on youtube! i never know if any of my ““advice”” makes sense, but i hope this does, or that it helps in some small way!! ♡

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi! I was a forensic anthropology major, which means bones actually were part of my curriculum! Like, the entire focus of my degree is on recovery and identification of skeletal remains. Not in a historical sense, that's bioarchaeology (or at least, was at my university), but in a modern crime scene sense. Add to that the fact that I'm nonbinary, and I feel pretty damn qualified to speak on this issue. I'm going to add a read more because I can go on and on about this. Bones are a special interest (hence the reason I majored in forensic anthropology).

So for starters: when we did sex estimation (that's the specific term used by the professors and curriculum I went through), literally the second slide (after the title) was about sex vs. gender. I had this discussion in two different classes (forensic anthropology and bioprofile). We had a full discussion, in class, about how we can only do very specifically sex estimation and we cannot speak on gender and how a person may have identified. I remember the very specific example of "we could find a body with 'female' trappings (breast implants, 'feminine' clothing, etc.) and if the bones trended male, we'd still have to say it was male, no matter the other evidence. That wouldn't be ignored, but it wouldn't be part of our sex estimation.

As forensic anthropologists, we are only capable of looking at the physical evidence. And we don't interpret other evidence found alongside remains. Our specific focus is the remains themselves. All we do is look at the bones and what they tell us.

Next up, you may have noticed that I used the term sex estimation. All our procedures are listed as estimations, in the classes I took. It's fully not possible to be 100% sure. But Kris, you say, aren't 'male' and 'female' bones different? Yes, but sexual dimorphism isn't black and white. If bones have 'female' traits, then we can assume with a reasonable degree of certainty that the individual was, at the very least, afab. However, there are documented examples of afab skeletons having more 'masculine' traits. You can see this even in looking at women across the world (especially in instances of athletes being questioned or 'accused' of being trans). Even with the use of programs like Fordisc, we can't get an exact result. I once had a prof say that we could plug the measurements of a soccer ball into Fordisc and it would still spit out a sex and ancestry estimation.

Additionally, sex estimation is only one of a number of procedures used. It's the one we're 'best' at, as there are only two options--once again, sex, not gender. (I once had a professor, not thinking, say "we're really good at sex!") However, we also do ancestry estimation, height estimation, identifiable features (such as op's "piece of metal permanently glued to the back of my teeth," which I, myself, also have). Dental records are used, medical records, medical ID numbers on any implants, etc. Sex estimation is just one of many tools in our toolbox, as a piece of a complete biological profile, and not the entirety of it.

Lastly, I mentioned that I myself am nonbinary. I dislike being called 'female' in my real life, but if forensic anthropologists (or even bioarchaeologists, though I'm going to focus primarily on the forensics side here) are examining my skeletal remains, I probably have bigger things to worry about than being misgendered--or nothing, rather, to worry about, as I don't believe in an afterlife. If them calling me 'female' helps identify my remains and bring closure to my loved ones, then that's more than worth it.

I don't have the time to pull out my old textbooks right now, as I am taking a break from my actual assigned task to infodump about bones and sex estimation, but if anyone is interested in a followup, either shoot me a message or an ask, and I will be more than happy to pull out textbooks and any notes I still have (I've been through two laptops since college, so I'm not sure I still have access to my notes) and give you some more information!

“When they examine your bones in a thousand years, you will only ever be seen as your biological sex”

1. I’m very flattered that you think my skeleton will be examined by scientists. Thank you for believing in my longevity.

2. When I’m a skeleton a thousand years from now, I plan on being dead so tbh I don’t see this being an issue.

3. I have an anthropology degree and I’ve worked with bones (not my focus, but it was still part of my curriculum), and yes we do use terms like “female pelvis” or “male proportions” when discussing remains. Even though I’m a trans person, I’ve never once been bothered by this. Gender and sex can exhibit themselves differently in a variety of contexts and language can adapt accordingly. Tbh I’m more concerned about my job security and my access to equal healthcare, rather than the gendered language my physical anthropology instructor uses.

4. In studying these bones, I can say that the sex or gender of the specimen I was looking at was the least interesting thing about them. Do you think archeologists thousands of years from now will care what biological sex I was? No, they’d probably wonder why I have a piece of metal permanently glued to the back of my teeth. Or the fact that my jaw is misaligned. Or what my joints can say about my daily lifestyle and level of movement. These details can help paint a broader picture of what life looked like back then on a physical level. That is the story my bones tell, not the shape of my pelvis or brow ridge or whatever.

5. Ur mom examined my bone last night 😂✌️🤙👅👅

51K notes

·

View notes