#the real world is our singular point of reference for fiction anyway

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Friday Night Lights: A Non-American’s Guide to American Football

https://ift.tt/3zYMt15

Friday Night Lights is now back on Netflix and you have to watch it.

Just to be clear, that isn’t a request – it’s an order. The NBC football drama is simply one of the most affecting, thrilling American TV shows of all time. Though premiering in 2006, the show can mark its lineage all the way back to a true story from the late ‘80s. In 1990, sports journalist H.G. “Buzz” Bissinger published the non-fiction book Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream. The book follows the story of the 1988 Permian Panthers high school football team in Odessa, Texas as they make a run for a Texas state championship.

The book was adapted into a Peter Berg film of the same name in 2004, starring Billy Bob Thornton. The story of the Permian Panthers was dramatically rich enough to conquer two mediums already, but when a third was announced in the form of a TV series for NBC it seemed like overkill. Did the world really need more high school football drama after a successful book and movie? It turns out that the world really did.

Friday Night Lights, the TV show, further fictionalized Bissinger’s story. Odessa, Texas becomes the fictional Dillon, Texas (though the Permian Panthers logo remains a big yellow “P”). Kyle Chandler steps into the role of a new coach, the magnanimous Eric Taylor. Shot in a cinema verite-style where blocking is optional, Friday Night Lights makes the viewer feel like they are just another Dillon citizen, desperately dreaming for a state championship. Above all else, this empathetic show never speaks down to its small town characters.

As previously stated, Friday Night Lights is a must-watch. But if you’re one of our many non-American readers (Hello, everyone! I see you out there, writing “s” in words that need “z”), the football angle may seem like a real roadblock. So let’s tear down that roadblock. American football is the most popular sport in the United States but also perhaps its most impenetrable. The rulebook is thick and its connection to American culture deep. What follows is an attempt to explain American football for non-American viewers who are hesitant to tackle the show. Hopefully this will also prove useful to existing Friday Night Lights fans who have some questions about the game.

To simplify matters, we’ve broken our football school down into three parts: The Different Levels of American Football, which explains the sport’s place in American culture and why high school football is a big deal; The Rules of American Football, which is as succinct a distillation of how the game is played as possible; and The Strategy of American Football, which examines whether Eric Taylor is even a good coach anyway.

The Different Levels of American Football

Football is a pervasive force in American society. The highest level of play in the country (and the world) is the National Football League in which 32 teams of well-paid professionals compete against one another. The NFL is the richest sports league in the world by revenue and its championship, the Super Bowl, is usually watched by roughly 100 million people per year. Football’s influence doesn’t begin and end with the NFL though. The NFL doesn’t have a minor league or development system, so those interested in watching younger athletes are able to do so by following the sport on the collegiate or high school level.

College football is a huge deal. Some major universities’ football stadiums can house upwards of 100,000 fans. Four-year universities and colleges across the country field their own football teams that compete against one another in 12-game seasons (before a postseason consisting of “Bowl Games” but that’s too complicated to get into right now). Football at the collegiate level contains hundreds of teams split up into different leagues based on size and different conferences based on geography (for the most part). There isn’t any promotion and relegation like in European football leagues but if an institution grows big enough they can secure an invite to a higher level.

Though the decision-makers of the sport like to pretend it’s an amateur exercise and the players are not paid, college football is really a multi-billion dollar business. In fact, college football’s governing body, the NCAA, was just spooked enough by a U.S. Supreme Court decision that it allowed its athletes to finally pursue “Name, Image, Likeness (NIL)” deals in which they are allowed to make money from personal sponsorships.

Read more

TV

25 Best Sports TV Shows: Cobra Kai, Ted Lasso, and More

By Alec Bojalad

TV

12 Best Movie and TV Quarterbacks of All Time

By Chris Longo and 1 other

Then we come to the high school level of football. Longtime viewers of American teenage dramas may have a pretty good idea of what a U.S. high school is now but here’s a primer for those who don’t. High school is the highest level of free public education in the U.S. before the more academically (and financially) strenuous college system. High school follows eighth grade (which together with seventh grade usually comprises of “middle school”) and consists of freshmen (ninth graders or 14-15-year-olds), sophomores (tenth graders or 15-16-year-olds), juniors (11th graders or 16-17-year-olds), and seniors (12 graders of 17-18-year-olds).

In some areas of the country, high school football is a bigger deal than college football or even the NFL. Though this level of the sport is played by essentially children, a high school football team may be the only competitive sports enterprise within hundreds of miles for some communities. This is particularly true in the massive U.S. state of Texas. Every region of the U.S. loves football, but passion for the sport is particularly acute in the Southeast, Midwest, and Texas. West Texas, where Friday Night Lights is set, is really high school football mad. The region is distinctly rural and far removed from the state’s three big cities – Houston, Austin, and Dallas. As such, high school football is the singular cultural force that many oil-drilling West Texas communities rally around.

High school football leagues across the country differ considerably, but like in college football, schools are generally grouped together by size and funding. Public and private high schools are able to compete in the same sports conferences as long as they have similar enrollments and budgets. Typically a high school football season consists of only 10 games (football is a physically brutal sport and as such plays far fewer games per year than other sports like baseball, basketball, or soccer). The regular season is usually followed by a bracket-style playoffs culminating in a state championship. There is no country-wide tournament, which is why “winning state” is the ultimate goal in Friday Night Lights.

The Rules of American Football

I won’t lie to you: this is going to be difficult. Explaining any sport from scratch is a tall task, let alone a sport as complicated as football. Let me attempt to do so from the ground up and please be patient. There will be some visual aids as well.

First, it’s probably helpful to know about the field that football is played on. There’s a reason why in some European markets that the sport is known as “Gridiron Football” and that’s because the field resembles a cooking utensil known as a gridiron.

Every American football field consists of 100 yards (split into two sides of 1-50 yards). At the end of each side of the field is an “endzone.” A player entering into the endzone with the football is called a “touchdown” and nets a team six points. At the back of each endzone are the goalposts – yellow tuning fork-like structures that the ball is occasionally kicked through for more points. These are akin to rugby’s goalposts but slightly differently shaped. Let’s table the whole kicking thing for now and focus strictly on the action on the field.

The goal of football is to enter into the endzone with the ball to score points and have more points at the end of the game than the other team. A football game is 60 minutes, split into four 15-minute quarters (with a lengthy halftime break after the second quarter). Eleven players take the field for each team, one side on “offense” and one side on “defense.” A coin is flipped at the beginning of each game to decide who gets to start as offense and who gets to start as defense. The team who began the game on defense will get to be the offense at the start of the second half.

The offense is charged with advancing the ball 100 yards down the field into the end zone, while the defense is tasked with stopping them by tackling the person with the football to the ground. The offense is granted four tries or “plays” to try to score. The action isn’t continuous in American football like it is in European football. After a team runs a play to attempt to advance the ball, they get a 40-second break to plot their next play. A play simply refers to the action on the field that the offense takes to get down the field. It begins with the “center” “snapping” the ball to the “quarterback” behind him and ends when the offense either scores (rare) or is foiled in some way – whether that means being tackled in bounds, stepping out of bounds, or throwing the ball out of bounds. Here is a chart of the typical football positions.

The offense’s two most reliable ways of advancing the ball downfield are either throwing it or running it. On a running play, the quarterback (Jason Street or Matt Saracen in Friday Night Lights) will receive the snap and hand it off to a running back (Smash Williams or Tim Riggins) who tries to run the ball upfield while his teammates block for him. Alternatively, the quarterback can throw the ball to an open wide receiver as long as the throw originates from behind the line of scrimmage (the area on the field where the play originated).

Four tries to reach the end zone are rarely enough opportunities for the offense. Thankfully, that’s where “first downs” come in. If the offense advances 10 yards, their “downs” or attempts to score reset back to the full four. That’s where terms like “1st and 10” or “2nd and 7” or “4th and 1” come from. The first number refers to which “down” or attempt the offense is on (1, 2, 3, or 4) while the second number refers to how many yards they need to reach to achieve another first down. Due to penalties or a player being tackled well behind the line of scrimmage (called a “sack” or a “tackle for loss”), the number of yards needed to reach a first down can exceed 10. One time in 2012, the Washington Football Team even had a “3rd and 50”, meaning they needed to move 50 yards for a first down.

If the offense fails to score or get a first down while on fourth down, possession of the ball is granted to the other team on the same spot that the offense failed. This is called a “turnover on downs.” The team that was previously on offense will bring their defensive unit into the game while the other team will bring their offensive unit. At the collegiate and professional level, players usually only play on one “side” of the ball – offense or defense. In high school, where the level of talent is more inconsistent, it’s not uncommon for several players to be on both the offensive and defensive units. This doesn’t come up much on Friday Night Lights though – for the most part the offensive players stay on offense and the defensive players stay on defense.

It is possible for the defense to force a turnover in other ways beyond just a turnover on downs. If the offense drops or “fumbles”’ the ball and the defense recovers it, it belongs to them. If the defense catches a ball thrown by the offense it is an “interception” and the offense suddenly becomes the defense and the defense suddenly becomes the offense. This situation factors prominently in Friday Night Light’s first episode.

Turnovers are awful, so the offense has a couple of tools to combat them. At any point during their drive down the field, the offense can choose to “punt” the ball. This means that if they’ve reached 4th down and are unlikely to convert a first down (if it is 4th and 10 from their own 30 yardline for instance), they can choose to have a kicking specialist called a “punter” enter the field. The punter receives the snap, tosses the ball up in the air, and punts the ball far down the field to the other team to catch and try to advance. This is a surrender from the offense but at least they’re making things a bit more difficult for the other offense by pushing the new offense further down the field. Punts rarely factor into Friday Night Lights as they aren’t particularly interesting.

Alternatively, if the offense is close to the end zone but not close enough that they’re confident they can reach it, they can attempt to kick the ball through the aforementioned goalposts for three points. A “kicker” is brought onto the field and attempts to kick the ball through the goalposts from the ground. A “holder” is allowed to hold the ball upright for the kicker but the ball must be touching the ground for the attempt to count.

Let’s delve a little further into the scoring system. We’ve mentioned that kicking the ball through the uprights is a field goal and nets three points while carrying the ball into the endzone is a touchdown and nets six points. But there are a couple other ways to score in football as well. After a touchdown is achieved, the offense is immediately granted the opportunity to score again. They must choose whether they want to kick the ball through the uprights from extremely close range (which nets one extra point) or to try to reach the end zone again from extremely close range (which nets two extra points). Additionally, if the offense is tackled in their own end zone, it nets two points for the opposing team and they receive the ball back via punt. This is called a “safety.”

To recap:

Safety: 2 points

Field Goal: 3 points

Touchdown: 6 points (+1 for a field goal attempt, +2 for a scoring attempt).

This means that football scores can generate pretty much any result other than 1-0 or 1-1. Typically a “normal” scoring game will be somewhere between the 20-40 range in divisions of 7 or 3. A score of 35-28 is a pretty usual final football score.

Still confused? That’s understandable. Football is a fairly confusing sport at times. But hopefully you are a little better equipped to understand the action on the field in Friday Night Lights. The show certainly isn’t trying to present a complicated depiction of football. Armed with the basics, you should have a rough idea of what’s happening during all the football action.

If you feel like you’ve mastered the basics, feel free to move on to the final section of this piece.

The Strategy of American Football

The only constant in football is change. The rules of the sport are tweaked every single year and sometimes the sport undergoes truly massive alterations. In fact, the forward pass itself (now a staple of the game) wasn’t even legal for the first few decades of football’s existence. As such, the offensive and defensive strategies of football are in a constant state of flux.

What’s interesting to note about Friday Night Lights is how old-fashioned its depiction of football appears to be at the series’ beginning. Keep in mind that this story began with the 1988 Permian Panthers. So despite premiering and taking place in 2006, the Dillon Panthers offense looks quite antiquated at first.

The Dillon Panthers open the series as a run-first offense in a “Wing-T” formation. Running back Brian “Smash” Williams is the cornerstone of the Panthers’ strategy because back in the ‘80s and ‘90s, athletically superior running backs were usually the most dominant force in any high school offense. The Panthers plan of attack is to have a fast tailback (colloquially called a “running back” because they begin the play in the backfield and then…run) and a strong fullback in the backfield alongside the quarterback. The Panthers’ plan is to snap the ball, give it to the fast guy, have him follow the big blockers, then rinse and repeat.

Interestingly enough, the show uses the primitiveness of the Panthers’ offense to its advantage in later seasons. When some parents and Panthers boosters (literally just rich people that support a high school or college team) want to oust Coach Eric Taylor, they point to his inability to change with the times and create a sophisticated passing attack as one reason. Coach Taylor does eventually attempt to implement a “spread” offense.

Spread offenses were all the rage at the high school and collegiate level in the early aughts. The “spread” strategy refers to “spreading” three to five wide receivers on the line of scrimmage to force the defense to cover them man-to-man. Defenses are always strategizing just like offenses, and by forcing the defense to spread out and guard many receivers, it takes away a lot of their more sophisticated coverage options (like double-teaming or divvying up the field into “zones” of coverage).

In later seasons, when Coach Taylor gains access to a fast, dynamic quarterback, he incorporates a bit of the “option” into his spread offense. This is where the QB uses the spacing from the spread to scan the field, analyze certain players’ positioning on the defense, and decide to pass the ball, hand off the ball, or run the ball himself.

Based on all this, it sounds like Eric Taylor is a pretty brilliant coach, right? Well, not exactly. The internet is littered with breakdowns of Taylor’s strategy from smart football minds. Most of said articles criticize him on two big fronts. The first is his tardiness in adapting to a pass-heavy offense. The second is his absolutely abominable clock management. Since the clock counts down in American football and there is no stoppage time, managing time is a huge part of a coach’s responsibility.

Since the show naturally wants to inject some drama into its football scenes, the Dillon Panthers as coached by Eric Taylor often have next to 0 clock awareness. This breakdown even notes than in the pilot episode, the Panthers somehow only move the ball 30 yards in five minutes of gametime. That is…pretty curious.

Also, while it’s not uncommon for a head coach to specialize in either the defensive or offensive side of the ball, Eric Taylor’s is particularly offensive-focused. Defensive plays aren’t as exciting to depict on television, so Coach Taylor is rarely shown coaching up the defensive half of his team. That’s a pretty big blindspot when it comes to head coaching.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

Now that you’ve read through this full breakdown of American football, give Friday Night Lights a watch or a rewatch. Who knows – you may even be a sharper football mind than Coach Taylor at this point.

The post Friday Night Lights: A Non-American’s Guide to American Football appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3lnaaMj

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

How it got growing

I was originally going to call this post "How it got started" but the truth is, I started thinking about my necessary responsibility towards the world/creation after watching a film on Netflix: Okja. (Although, sadly, it really should have started when I came to understand for the first time that there is a designer behind the world, God, the Creator, and I am made in His image for a purpose - more on that later though.) Yes, it is fictional, and even fantastical, but the film drew its inspiration and data from real life practices. The film asks a serious question: can we justify animal welfare practices as 'ethical' just because they leave a small ecological footprint? Anyway, long story short, I decided to cut out meat from my diet. You can read my summarised version of when I first needed to think through my response here. As an evangelical Christian, perhaps in my naivety, I was somewhat surprised by the response of some evangelical Christians around me. I was judged as being theologically 'weak' (I even had a friend open the Bible with me to 1 Corinthians 8 and explain to me that it doesn't matter how our meat is killed or where it comes from...to which I responded, as gently as I could, that the same writer writes what he does in Romans 14...and also the/my issue was not with eating meat but with the welfare of animals in the meat industry, which involves completely different theological considerations, namely understanding God as the Creator) or, I was judged as being "one of those vegans" (a very sad stereotyping of individuals into a singular political movement). At first, I felt anger and disbelief: how can you not feel that this is wrong? How can you think it’s fine? I wanted to convince people to do what I do. But God was nudging my conscience: I needed to make sure I didn't let pride dictate how I responded to these brothers and sisters of mine. It was not right to tell them to live exactly like me (God made us each individually unique so we would express Him as His children in different ways, according to how He has made us and where He has placed us), or think that they were less than me because they didn't feel and think as I did - as if I know the best way to live. After all, I am also waiting for God (I am not the Saviour) to restore everything and make it as He intended. I am living in light of that hope, even as I mourn now (and increasingly, as I learn of more that is wrong with the world) at the brokenness of everyone to everyone and everything. But it did start my questioning and thinking: why don't evangelical Christians have a strong theology and clear ethic and lifestyle of creation care rising out of God as Creator? (Also to be discussed in a later post.) Why should it surprise evangelicals that a natural expression of that could be vegetarianism? It is almost like there isn't a place or framework for thinking about such a thing, let alone do such a thing. (I have since learned that this is not true, but this is what I felt at the time.) I am growing in conviction more and more that being a child of God is about living out/bearing His image in His world, bringing redemption on all levels, by His power. This is what I am redeemed for. This is what I am destined for. And this is why Jesus came. Yes, to bring me reconciliation with God (through his death on the cross - bringing justice from judgment, freedom from guilt and slavery to sin, honour from shame, freedom and power from fear and powerlessness) but this begins the process of reconciliation to self, others and the world. Mike Koheen drives home this point, and more, brilliantly:

If redemption is the restoration of the whole of creation, then our mission is to embody the good news: every part of creational life is being restored. The good news will be evident in our care for the environment...If redemption were merely about an otherworldly salvation then our mission would be reduced to the sort of evangelism that tries to get people into heaven. We would be forced to surrender most of God’s creation to the evil powers that claim it for their own...

That was back in 2017. God has shown me many other ways since then of how creation care is an essential part of my growing discipleship, my growing to become what I am: child of God, redeemed image bearer. It is intertwined deeply with loving God and loving neighbour in so many different ways.

My minister recently gave me a book titled "Coming Home" (a thoughtful title!) by an Australian Christian and political economist who has practically lived out the things he discusses in personal and professional ways. It looks at, what the author considers, seven key areas of discipleship when it comes to ecology and economics, where the home is the central place for getting started and growing*:

#hospitality: opening our homes

#workandleisure: Sabbath-centred living

#consumption: a right relationship to things

#sustainability: an earth care-full way of life

#giving: living with an open hand

#savingsandinvestment: the building up of one another

#debt: freedom to follow God

I cannot recommend this book to you enough. It is theologically sharp and deeply thoughtful, culturally relevant, and incredibly practical. In fact, each chapter is structured around these three questions: What’s the problem? What does the Bible say? What should we do?

My husband and I read this book together and resolved to take up new habits in each of the areas every six months, ensuring we continue to grow in this area of discipleship in an everyday way, that is, in our home and lifestyle. We want to share our journey of growing in thinking about, understanding and appreciating God's creation and our cultural mandate towards creation care, and how we're practically doing it in our little corner of the world. It is by no means prescriptive! It is going to be an account of our honest and humble reflections and actions. We hope it encourages you and gives you food for thought and action in whatever way God might be bringing new convictions to you about what your discipleship looks like in light of the cross and looking forward to the full restoration of His world. We hope that you would be willing to share with us your thoughts along the way - iron sharpens iron.

*Author Jonathan Cornford says “home economics is central to the reconciling of economics and ecology that lies at the heart of humanity’s great challenge in the 21st century...I have come to the conclusion that reclaiming a Christ-centred practice of home economics is central to our own spiritual health and to our witness in the world. The Greek word for ‘house’, oikos, is the root word from which we get economics (oikonomia), ecology (oikologia) and ecumenical (oikumene). Economics describes the management and ordering of the work, consumption and finances of a household...Ecology describes our attempts to understand the great household of nature and, in particular, to understand the interdependent relationships that support the functioning of that household. We have tended to think of economics and ecology as two separate spheres, when in fact the human economy exists entirely within the great household of nature and still depends entirely upon it, even if modern urban life gives us the illusion that we are somehow independent of nature. Ecumenism describes the movement towards unity within the household of God, usually referred to as ‘the church’. It is based on the recognition that belonging to Christ draws us so deeply into relationship with others that we are members of a single body. Generally, this last ‘household’, the church, is seen as having little to do with the other two. Moreover, in practice, the church even tends to have little to do with the ways in which its members run their homes. However, if we accept, as the Apostle Paul tells us, that faith in Christ requires presenting our ‘bodies as living sacrifices’ - that is, conforming our day-to-day bodily and material existence to the way of Jesus - then we must understand our individual households as not only the base of our participation in economy and ecology, but also the core site in which we enact or deny our membership in the household of faith in the hundreds of choices we make every day. What’s more, if we understand the household of faith as merely the first-fruits of the great reconciliation that God intends for the whole created order, but is yet to be accomplished, then a fuller understanding of the household of God should expand to encompass the whole household of nature, the human economy that exists within that and our own individual households within that.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

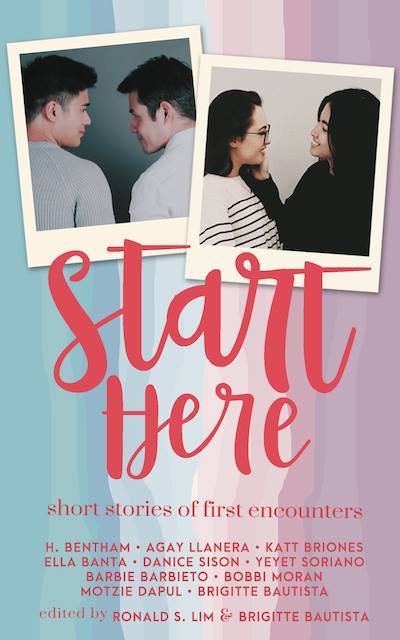

Start Here, Stories of First Encounters

Let me just say this right off the bat, I’m giving this 6 of 5 Stars! First of all, the editors and my co-authors deserve the 5.5 of 5 Stars. This is my favorite book this year, cheesy for me to say, but it is! I’m giving a half star more for my own story because I’m very proud of this, okay? :P I’ll talk more about that on a separate blog post, haha.

To begin, I want to thank the editors (and our PM, Hi Mina!) for coming up with this anthology. The intros by Ron and Brij, in itself, were already strong messages to those who are looking for contemporary romance that represents Filipinos of this time, LGBTQIAP or not. It perfectly put out the reasons behind the conception of this anthology, as well as the hope that this sparks a flame towards more Queer Romance and Queer HEA in Philippine Literature.

1. In the Moonlight by Agay Llanera

This was a sweet start to set the tone for the rest of the stories. It’s an awesome sequel to my other favorite, Another Word For Happy. And like what I said in my review for AWFH last year, Caleb seems to have been made after my own heart.

I wish I was exaggerating, but the indecision, the awkward reaction to ‘the kiss’, the hyperawareness to the smallest of things, IT ME! When I was Caleb’s age, at least. LOL. And I’m sure a lot of gay people (maybe not even gay people, everyone, really) will find it relatable one way or another.

What Caleb is better than me, though, is his courage towards the end of the story. He did something I never would’ve been able to do. And I hope when others read this, they’d be inspired to be braver, too.

2. Come Full Circle by Bobbi Moran

I love me some slow burn romance and huhu, the slow burn in this one killed me (in a good way!).

This short felt quite episodic as the characters are shown through different stages of them finding themselves – and eventually, love – but that slow progression allowed me to really root for them to be together at the end.

I found the attention to detail fascinating (especially the architectural ones when Alana and Marion went on a holiday) but what I loved most about this is the accuracy of tiptoeing in a relationship when one is still unsure where the other one stands. I mean, relationships are already complicated without the whole guessing-and-hoping-the-other-one-plays-on-the-same-team narrative, but add in sexual confusion (and tension!) and you’re in for a wild, but nonetheless more interesting, ride. This story tied to a full circle satisfyingly.

3. Gorgeous by Motsie Dapul

This is probably my first F/enby romance and it certainly lived up to its title. This might also be the first fiction story I’ve read using the singular they/them pronoun and while it took me about a minute to re calibrate my [faulty] sense of grammar, it wasn’t jarring and it told Jays and the MC (I’m not 100% sure she was named, I need to reread the story, stat!)more genuinely for me.

It is also somewhat a variation of the enemies to lovers trope which is always interesting. I’m happy to note that there is grovel. :)

I think what I want to focus more about this story is how something that happened years ago, something that seemed small and irrelevant to you, might mean a whole different world to another person. And simple things like words said haplessly, or actions that weren’t well thought of in our youth, could still impact us as adults no matter how much we’ve changed in the time in between.

This story tells and awesome story of discovering one’s self, discovery of love, and acceptance of the MC’s past, present and future with Them. :)

4. Shipping Included by Danice Sison

Can this be any cuter?? <3 <3 <3

I will admit that I didn’t get all the KPop references but I know those who are knowledgeable (and obsessed) with oppas will appreciate and enjoy this.

Done in alternating POVs between the protagonists, David and Kiko, the story’s strength lay on the well-rounded characterization of the heroes, as well as the kids who made their meetcute extra cute! There is a glimpse of what it must be like to be a Filipino KPop fan while also focusing the spotlight on those who don’t share the dedication but support their loved one’s hobbies nonetheless.

The Kuya and Tito may not be in their girls’ fandoms but Kpopocalypse gave them (all of us, really) a different reason to swoon and make fingerhearts at each other.

5. Delubyo by Barbie Barbieto

This is beautifully written.

This was the first work from the author that I’ve read and I loved it so much, it made me seek out her other work. Haha. The style and flow of words are smooth and easygoing, it hooked me up real quick.

Add to that is Pebbles’ odd four-month relationship rule which I thought was mean at first, but actually makes so much sense and is understandable from someone who’s constantly afraid to put her heart on the line. Still, I don’t tolerate it. (I loved this so much, I’m super invested and I want to have a talk with Pebbles bec huhu, the poor ex-girlfriends! LOL)

I love the progression of her feelings towards Gabrielle, told brilliantly somewhere in the middle of the story – after that awesome beginning! It made the ending such a relief and a source of immense kilig!

6. The Other Story by H. Bentham

*sly grin emoji*

7. Blooms and Hues by Ella Banta

I loved the softness of the themes in this short story, reminiscent of Gay YA fiction I used to devour in college (from foreign authors like Brian Sloan, Alex Sanchez, John Hall, etc.) and the short films I still find on YouTube from time to time.

It is a lovely addition to this anthology, despite not being heavy on the romance like the other stories, especially since being queer in this country, love, relationships - and matters of the heart in general - are less likely to be this soft and dreamy. (At least during my time as an actual young adult. IDK, maybe kids these days are allowed this gay tenderness we weren’t given access to. It wasn’t even such a long time ago, I mean…anyway, that’s not what this review is all about. I got distracted. lol)

The artistic MC and LI are adorable. And flowers! I’m never not in love with stories where flowers come into play.

8. Another First by Yeyet Soriano

I admit that I felt scared to continue with this once it was established that Jess, the MC, is in a long term relationship at the beginning of the story. I dislike scenes with messy break-ups due to cheating, but I soldiered on and was greatly relieved that this didn’t go that way.

I liked that the characters acted like the adults that they are and that this did not turn into a rehash of popular love-triangle telenovela plots. I especially loved the part where things had to settle down and fall into place for all characters (Jess, Lili and even Matt) separately at first – on a personal level – before the romance could be resolved. It showed a healthy depiction of self-discovery and acceptance a little bit later in life.

9. Luck from the Skies by Katt Briones

This one I’ve actually read before the book came out and ugh, rereading it second, third and fourth time did not make it less wonderful! The characters have supporting roles from Katt’s other book, Chasing Mr. Prefect, but the timeline here is before that book’s time.

I liked the fictional artista/modeling angles and the progression of friendship between Chan and Asher towards a romantic ship (#ChaSher5everr!!!). The rainy weather theme is also very Filipino and how it plays in the advancement of the plot is just brilliant! And kilig! So kilig!

Sab is defineitely a scene stealer (I love bestfriends!) but since the romance was so strong in the first place, she didn’t overshadow my boys. LOL.

Also, prepare to crave bulalo!

10. Lemon Drop Friday by Brigitte Bautista.

“Here goes [Brij] again, making a mess [with my heart]”

When I was reading the review copy and got to this point in the book, I stopped for a full day before I started this story. Part of me knew I would breeze through it and I didn’t want the book to end just yet. And I was right.

Brij did it again! Made me fall in love with her mastery of words and then made me cry because this was so good and so satisfying.

I was highlighting passages throughout the book (for review notes) but with this one, I couldn’t even stop to highlight words, I just wanted to fully immerse in that universe and feel the love, and the fear of rejection, and the ultimate HEA where these messy girls finally, finally got together!

I have a favorite quote (aside from the mis-quote above. Lol)

“If she looked at me a tad longer, she would figure it out.”

Argh! MY HEART! I loved Tala’s POV so much! It’s quirky and funny and honest and SO relatable. I’m done talking about this because I WILL SPOIL IT FOR EVERYONE so please get the book and read it! :P

To end, again I want to thank everyone who worked (and continue to work hard to promote) this book! I cannot fully express into words how important this is to me, as well as to others who might need these stories in their lives (whether they know it or not). I hold this dear this not because it is among the first queer books from #romanceclass, but more because all were written with wonderful skill and heart. Each story offers something unique for the reader who might be reading queer for the first time as well as someone looking for themselves in the written page,

We yearned so much to be represented well. We craved for stories we can connect to on a deeply personal level. We waited for our happy endings, in fiction at the very least.. This is definitely the beginning of us getting all that. And more.

Blurb:

There’s a first time for everything. Gatecrashing a KPop concert with an oppa in a business suit. Taking shelter from the storm with the girl you’ve been meaning to shake off. That kiss that blurs the line between friendship and something more. A one-night stand (or, is it?) with your best friend from across the hallway.

Dive into these 10 stories of first encounters – unapologetically queer, happy endings required, with a smattering of that signature #romanceclass kilig. Whether you’re recalling your own firsts or out there looking for one, there’s a story in here for you.

So, go on.

Turn the page.

Start here.

Edited by Ronald S. Lim and Brigitte Bautista. Featuring short stories by Agay Llanera, H. Bentham, Ella Banta, Danice Sison, Yeyet Soriano, Barbie Barbieto, Katt Briones, Bobbi Moran, Motzie Dapul, and Brigitte Bautista. This anthology contains M/M, F/F, F/NB romance stories with happy endings. Some stories have a high heat level.

Release Date: January 27, 2018

Book Cover Design: Dani Hernandez

Additional Photography: Alexandra Urrea & Chachic Fernandez

Buy Links:

Pre-order Start Here on Amazon: bit.ly/rcStartHere Order Start Here on paperback (PH only): bit.ly/StartHere-PrintPH

Add Start Here on Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/37880247-start-here

Author links:

Katt Briones: @kttbri (Twitter& IG)

Ella Banta: @gabbie_ellaine (Twitter) , @ellamaepot (IG), gabrielluna.wordpress.com (blog) , https:// www.facebook.com/ ellabantawriting/ (FB)

Agay Llanera: http:// amzn.to/ 2k2gj34.(Amazon)

Yeyet Soriano: @ysrealm (Twitter & IG) @Yeyetsorianowrites (FB), www.yeyetsoriano.com (blog), [email protected]

Danice Sison: @hastyteenflick (Twitter)

Bobbi Moran: [email protected]

Motzie Dapul: FB.com/atemozzarella, FB.com/atemozzarellastories, @atemozzarella (Tumblr) , mozzarellastories.wordpress.com (blog), motzie.dapul@ gmail.com.

Barbie Barbieto: @barbiebarbieto (Twitter), barbiebarbieto.com (blog)

H. Bentham: this is me. heh.

Editors:

Brigitte Bautista: @brijbautista (Twitter & IG), brijbautista.wordpress.com (blog)

Ronald S. Lim: @tristantrakand (Twitter), [email protected]

1 note

·

View note

Note

does fiction have an impact on reality?

this is a debate i’ve thought a lot about and it’s something i’m really cognizant of as i write my own fiction. because fiction aims to portray human experiences and emotions, good fiction inherently has an impact on how the reader understands the experiences it portrays. subconsciously or consciously, readers take those assumptions and impressions into reality to varying extents. the answer to whether or not it impacts reality is unquestionably yes. fiction is both an echo and a mirror of the world, regardless of whether or not it was intended to influence opinion on reality. it’s unavoidable.

that being said, i don’t think it’s accurate or helpful to judge art with a solely reactionary lens, and that’s where this question gets complicated.

fiction can be a powerful force in driving cultural conversations, and can either question or reinforce societal assumptions with how its portrayals match up to the reality it enters into. it’s easy to fixate on the discourse fiction inspires when there’s entire websites and industries dedicated to it, especially when those conversations are in-depth, rapid, and conflated again and again to broader cultural/societal concerns. but it’s important to remember that a lot of this discourse is more self-contained and niche in the grand scheme of things than we want to admit. fiction can have a monumental impact on isolated circles, individuals, and flash cultural movements without really being a drop in the ocean to reality as a whole. to some people, and certainly to those within that space, this still matters a lot. it intimately impacts their reality. we can admit that impact is real and important without overstating its reach.

for example, something like sansa’s rape scene in game of thrones may help spark a very real look into our voyeuristic obsession with female pain, but 1. that conversation is very unlikely to be the primary impact of game of thrones as a piece of fiction, and 2. is really only going to take place in circles looking specifically at the implications of fictional narratives in light of our current reality. you could make a pretty strong argument that the lasting impact of game of thrones as a piece of fiction might very well be how it inspires discourse and think-pieces at a dizzying, astronomical rate. but it’d be very difficult to argue that it was directly correlated to the specific, unique narrative content of the show and that its status as an immensely popular TV program in a volatile cultural climate was incidental.

if your argument is that problematic scenes in fiction impact how we understand and deal with those things in reality, it’s more or less impossible to isolate the specific content from an audience that has already decided to use fiction as a mouthpiece for their cultural concerns in most instances. fiction, in this case, gives us a tangible way to illustrate and discuss a societal problem when it is reflected in its contents. by giving us a concrete look at the problem, we are able to have an understandable, clear conversation about how those implications play out in the reality that created it. but that problem isn’t being framed through the lens of game of thrones ONLY due to the way it was portrayed, because it’s not the ONLY way that conversation would ever take place. that specific portrayal may have sparked a uniquely intense and prominent conversation, but it only did so in a society already having conversation upon conversation about that subject, already deeply concerned about that problem, and predisposed to use popular media as a reference point.

you could argue that it’s still influencing reality because voyeuristic female abuse in fiction illustrates how pervasive and problematic it is in a way that real life on its own cannot. you could argue that its presence in popular media runs the risk of further normalizing and proliferating that tendency. you could argue that, even if it is culturally motivated and not a unique problem to any given piece of media, it has a heightened impact on reality because of the culture it’s being presented in. those are valid arguments. but they are arguments primarily concerned with the reactionary lens, which is first and foremost examining traces of reality in fiction in order to process that evidence back out of it. it is a valid, useful way to analyze the relationship between fiction and reality, but is ultimately only one of many. just like any singular critique of fiction, it’s never going to definitively prove it impacts reality outside of its own criteria. that isn’t inherently a bad thing. if we decided every incomplete critique was useless, we’d risk throwing out the entire discipline of literature.

that’s exactly why i have a problem when this sort of tumblr-esque ‘anything problematic in fiction has a direct and serious impact on real life’ is treated as a complete and indisputable way to measure the fiction/reality relationship, or when a black-and-white reactionary critique is used to render fiction either moral or immoral. (setting aside the debate on whether or not art even has moral quality within itself.) the idea that using any other criteria to look at fiction is irresponsible and harmful makes me nervous, because i fundamentally believe that looking through fiction in ONLY one direction is irresponsible and harmful within itself. fiction is an infinitely mutable medium and requires nuance and patience to fully understand, especially in the context of the world around us or human nature in general. people spend their entire lives looking at this shit, and there’s no cut and dry answer to how certain things should be portrayed, when they should be portrayed, and how they reflect or echo reality. acting like there’s a prescriptive methodology to analyzing that is dangerously naive.

the age-old ‘life impacts art and art impacts life’ equation is fundamental for a reason; it’s an ouroboros-like relationship of influence onto influence, but it’s also important to remember that life impacts life, and art impacts art. even in satire or other social critiques, fiction is inherently self-reflective, using the unique confines of the medium itself to portray absurdity. though its goal is to have the audience question and reflect on the reality in which it portrays, the only thing fiction can definitively, always be is just that: a portrayal. more often than not, art does not inspire a definitive change in reality as a whole as much as it inspires definitive change within itself as it interacts with its relationship to reality over time. the extent to which we use it to manipulate and conceptualize the world around us is often circumstantial. fear-mongering the inevitable push and pull of this process just isn’t that effective anyway.

#man i love this shit i wish i liked formal education more so i could do it all the time#i love you anon... i love you#Anonymous#witness testimony

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Cartridge: Everyday Conspiracy

((Hi all! as we move into our final piece on Firewatch, a reminder that you can support No Cartridge at patreon (www.patreon.com/hegelbon), paypal (www.paypal.me/hegelbon) and on twitch (www.twitch.tv/hegelbon). We also will soon be moving to another, singular website, so keep your eyes peeled for that! Onward and upward, thanks to your support!

Oh, and spoilers, as always.))

One of the more underreported weirdnesses of the American wilderness is just how many damn people go missing on a yearly basis in our national parks. Well, underreported may be unfair -- it’s not as if there are a lot of misconceptions about the dangers of parks, how easy they are to get lost in, and what can happen if one veers off the trail. But the cavalcade of paranormal stories -- some along the lines of r/nosleep style fiction, others in the realm of true conspiracy theories -- are a bit more subterranean.

Popularized largely by David Paulides Missing 411 series, the nefarious reasons for disappearances in our national parks have gained steam in a national moment where frankly most of us would rather learn about aliens, conspiracies, and the occult than actively engage in the world surrounding and vexing us. So whether it’s just the deeply fatal quality of the wilderness, tragic missteps, or something darker, we’re drawn to stories about the events we can’t readily explain that happen in areas we more often than not don’t really think about. Is it any wonder then that some of these theories end up looking more like questions about shadow governments, surveillance, or unseen forces? No, of course not -- but what’s underlying those theories, anyway?

The most gripping storyline in Firewatch, as I discussed in my previous piece, is the story of Brian Goodman and his father, Ned. Ned, years ago, had the job of the player’s avatar Henry, and Delilah, his friend, confidant, and psychological lover in the tower across the way, grew to have a fondness for Ned’s son, Brian. Brian was in the Shoshone National Park in defiance of state rules banning minors from the park during forest fire season. Delilah knew about Brian, but said nothing as he seemed to be enjoying the outdoors and was getting some time with his (fairly bad) dad.

You end up learning about Brian in fits and starts, first finding his backpack full of ropes that allow you to rappel down steep cliffs, and then hearing stories about his (importantly generic) Dungeons and Dragons campaigns that he played with Celia. By the time you reach the fort Brian had set up outside the cave systems that undergird the Shoshone, he’s almost like a third character in the game, a phantom that refers metonymically to the world outside of the park, the past and future of all the world spinning outside of your own personal soap opera.

And as it happens, you need a phantom to keep the massive complexities of the park and its residents in perspective as your own massive problem and conspiracy unravels in front of you. After finding two girls firing off fireworks and lecturing them to mixed results, you find your guardtower trashed, the phone lines cut, and a taunting set of panties left to identify the vandals. Unfortunately, the girls are missing when you find their trashed campsite, and they go missing completely.

Immediately, you are a suspect, as your character is the last to see either of them alive, and even Delilah delicately asks what happened to them and if you know...anything at all. You don’t, and suddenly the specter of disappearance is brought up -- a sheer drop, a drowning, a murderer. It’s unclear, but it’s also potentially incriminating to Henry.

And this is exacerbated by the discovery of “Wapiti Station”, a seemingly abandoned research station that is surrounded by a massive fence and is inaccessible to everyone, including rangers. The discovery comes after the girls go missing, and directly afterward, Henry is assaulted from behind after finding notes that dictate his and Delilah’s conversations, copying routes and exact diction. Suddenly, the two realize they’re being watched, and the teens disappearing seem like an harbinger of future danger than an isolated tragedy.

The danger continues to mount as both Henry and Delilah start to doubt each other, begin to see the entire forest as a sinister set of unspoken threats or misrepresentations. Quickly, after the introduction of Day 75, where Henry is sitting, legs dangling on a rock face eating a sandwich, the whole relationship unravels under the force of the threat of Wapiti Station, one part Paulides, two parts the spy novels littering the rangers’ stations in the Shoshone. The facelessness of your confidants suddenly become deeply suspect, and no one can be trusted -- the conspiracy is too wide to comprehend.

At the point at which Henry and Delilah decide to explore the caves -- convinced something must be down there that will lead to the Truth -- they think they are being framed for setting a fire at Wapiti Station, they assume they are being surveiled by sinister forces, and they fear for their lives. The conspiracy has deepened to an incredible degree, and the stakes have risen to levels that, had you asked in Day 1, would seem absurd. The cave, our firewatchers and the player all think as one, is where the solution will be found, the thread that unravels this entire terrible puzzle.

And of course it is. They find the dead body of Brian at the bottom of the cave and all intrigue stops. In quick order, the fire ravaging the Shoshone requires extraction of our protagonists, and we find out that Brian’s death has been the moving factor of the whole campaign of conspiracy. Ned, Brian’s father, has been trying to scare you and Delilah off the trail of his dead child, a child he has left to mummify in a cave while he hung out away from the law in a national park. The girls turn up in a local jail, and the intrigue of the game turns into nothing more than dueling codices -- trying to connect all of the dots while Delilah begs you just to leave it all be and get out before the forest burns around you.

But in the end, anything but the true conspiracy underlying the game is a disappointment to Henry and to the player, one that requires concerted effort to re-litigate. In the end, there’s nothing there but a body, but the conspiracy masks this much more tragic banality with the promise of horror and barely speakable governmental darkness. Killers, creatures, aliens, spies -- it all comes down to a kid who didn’t keep his balance while his dad forced him to climb.

This let down is natural, and a part of what’s at the core of all comic book, videogame, or otherwise “nerd” culture. There is no cabal of rich, callous murderers in Ciudad Juarez, there are just banal and horrifying killings of women. The loss of a child in a park is not an abduction by an alien or a cryptid; it is a deeply unfortunate and unavoidable moment of tragedy. Pop culture helps us to believe that the banal moments of our life that impact us the most are not base trauma -- the things that keep us from owning or engaging with our lives to the fullest -- but mobilizing forces to our continued revelation of a more profound world. There is no tragedy here, in other words, that isn’t a door to perception.

But this is also what conspiracies do for us. We use them to convince ourselves that there is some sort of deeper logic to the world around us as opposed to a series of unknowable tragedies. And who would a conspiracy appeal to more than a man who lost his wife to Alzheimer’s and a woman who lost everyone she ever got close to. The protagonists of the game need a conspiracy in the same way many lonely people through time have needed one. As The Last Podcast on the Left has surmised: people need the Hollow Moon to fill some sort of deep hole in their lives.

But what Firewatch shows us is that there is nothing at the end of the narrative other than a dead body and a lack of explanations. Videogames for ages have been teasing massive conspiracies only to provide let-down compromises, the actions of a few crazy men or women read into larger significance in order to justify the machinations of a larger videogame narrative. Firewatch seems to be going that way, and while any seasoned gamer is probably ready to be disappointed, the gut punch full-stop of the actual truth is worse. There’s nothing that can steel us for the actual truth, the fact that there is no darker secret to most of our lives than the fact that none of them ride on a clear narrative.

Firewatch gives us a ton of narratives, too -- Henry’s relationship with Delilah; the missing teens; Brian and Ned; the notes found throughout the park; the research center; hell, even the fires themselves -- all of which resolve into dust by the end of the game. There’s no ultimate point to anything Henry does in Firewatch, and that’s certainly not for lack of trying on Henry’s part. It’s due to the fact that, despite our best efforts, the banality and everyday randomness of life is more likely to hit us than a true novelistic arc. Far more common in real life, and far rarer in fiction, Firewatch gives us a look at what happens when we turn over all of the rocks and follow every lead to its very end: we feel cheated by the materiality of the real world, that ubiquitous presence that reminds us of the solidity and the unremarkable quality of life.

Conspiracies, in the end, are nothing more than a set of snapshots taken by a stranger.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Circles of tragedy and How To Act

Clare Finburgh, Senior Lecturer in Drama and Theatre at the University of Kent, responds to How To Act.

A circle. Anthony Nicholl, the “successful theatre director in his fifties” invited in Graham Eatough’s How to Act to give an acting masterclass, asks members of the audience to remove their shoes, which he then places centre-stage to form a circle. Nicholl marks out the circular space in which his participant, the young female actor Promise, will do improvisation exercises based on her own past.

According to Friedrich Nietzsche The Birth of Tragedy (1872), tragedy pulls “a living wall … around itself to close itself off entirely from the real world and maintain its ideal ground and its poetic freedom”.

[1]

Since its ancient Greek origins, tragedy has demarcated itself clearly as an art form distinct from the lives of the audience members watching it, a feature that the circle in How to Act recreates. In this, and in other respects, How to Act returns to the vast scope of the Classics. At the same time, How to Act expands classical tragedy in order to speak eloquently both to theatre today, and to politics today.In a number of respects How to Act, like the “prize-winning tragedians of ancient Athens” to which Nicholl refers, foregrounds its own status as art. Like a classical tragedy, How to Act features a chorus. The chorus self-consciously draws attention to the fact that what the audience is watching, is a piece of theatre. In addition, according to the French cultural theorist Roland Barthes, the chorus constitutes the very definition of tragedy, since it draws attention to the tragic dimension of the play by remarking on it.

[2]

How to Act differs, though, in that the members of an ancient chorus tend to pass judgement on the proceedings in the play, whereas Eatough’s chorus involves clapping and movement, which are performed in the circle. But in the extent to which ancient plays themselves featured song and dance,

How to Act does inherit from classical tragedy.Predating Nietzsche by over two millennia, the first theorisation of tragedy in theatre was provided by Aristotle, whose Poetics stated that the central tenet of tragedy must be one single, unified, clearly defined plot – what Nicholl in How to Act describes as “Proposition – dilemma – response. The fundamental building blocks of drama.” The circular space in which a tragedy is performed becomes a kind of boxing ring, a scene of combat in which conflicts are battled out until their final dénouement. Within the circle, the two conflicting worlds of Nicholl and Promise – male and female, European and African, older and younger, coloniser and colonised – clash. However, the plot in How to Act is far from straightforward. Eatough introduces a play-within-a-play device, where Promise, following Nicholl’s instructions, enters the circle and conducts drama exercises in which she enacts scenes from her childhood in her native Nigeria. When Promise reveals that Nicholl, who had formerly travelled to Nigeria to conduct research for his theatre practice, had no doubt had a brief affair with her mother, it is not clear if she is enacting a fiction, or whether she has actually come in search of the man who might be the father she never knew. Like the French author Jean Genet’s The Maids (1947), where two maids play at being a maid and her mistress; or indeed the most famous play-within-a-play of all, The Mousetrap in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1599?), levels and layers of fiction in How to Act become entangled, as it is never quite certain on whose behalf the doubled characters speak. Like Shakespeare before them, generations of playwrights have abandoned the unity of an Aristotelian tragic plot in favour of multiple interweaving narratives. Indeed, the mid-twentieth-century German playwright, director and theatre theorist Bertolt Brecht, to whom I come presently, argues that today’s world is far too complex to be encapsulated in a singular dramatic plot:

Petroleum resists the five-act form; today’s catastrophes do not progress in a straight line but in cyclical crises; the ‘heroes’ change with the different phases, are interchangeable, etc.; the graph of people’s actions is complicated by abortive actions; fate is no longer a single coherent power; rather there are fields of force which can be seen radiating in opposite directions.[3]

“The truth is that theatre is dying and we all know it”, declares Nicholl in How to Act.

Whereas Nietzsche entitled his major work The Birth of Tragedy, George Steiner in the twentieth century announced The Death of Tragedy (1961) – the name of his important study. Steiner argues, “tragic drama tells us that the spheres of reason, order, and justice are terribly limited and that no progress in our science or technical resources will enlarge their relevance”.

[4]

For Steiner and other Marxist theorists and theatre-makers, notably Brecht, the incontrovertible fate in tragedy is incompatible with a political commitment to the radical transformation of society: tragedy in art is anti-progressist because it reinforces political fatalism in life. It is important to note that Aritotle’s Poetics does not in actual fact mention fate, although ancient tragedies do often submit tragic heroes to their destiny. Sophocles’s Oedipus is the classic example: before his birth it was predicted that Oedipus would murder his father and marry his mother; and despite his and his parents’ lifelong efforts, this is precisely what takes place. The circle in Eatough’s How to Act thus denotes the inescapable circularity of fate.

The Algerian playwright Kateb Yacine, many of whose works were written during the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62), named his tetralogy of tragedies, which was inspired by Aeschylus’sThe Oresteia, the Circle of Reprisals (1950s). In this series of plays, as in Aeschylus’s House of Atreus in the Oresteia, a closed circuit of violence, an ancestral cult of violence, reprisals, revenge, fatality and failure, become inevitabilities for all of Algeria’s population. Kateb writes:

For me, tragedy is driven by a circular movement and does not open out or uncoil except at an unexpected point in the spiral, like a spring. […] But this apparently closed circularity that starts and ends nowhere, is the exact image of every universe, poetic or real. […] Tragedy is created precisely to show where there is no way out, how we fight and play against the rules and the principles of “what should happen”, against conventions and appearances.[5]

This resignation to a doctrine of circular fate is illustrated when Promise in How to Act says:

It’s all been written for us hasn’t it? Sometime in the past. Before we met anyway. Before you met my mother even. None of it could have been any other way. You thought you could make a difference. Control things. Control the story. But it’s not yours to tell. You’re just a part of it. Like we all are. You’re just in it. Subject to it. It’s all been decided. Who we are. What we mean to each other. How this turns out. I was always going to find you. Come back to you. Like a curse. Show you who you really are. A liar. That’s how this ends. There’s no escape.

It is precisely this belief in the circle of fate and the absence of a possibility for escape from this circle, that has been rejected by Marxist playwrights and directors like Brecht.

Instead of submitting to a destiny of suffering, for Brecht, characters – and the audience – must seek to understand the reasons for suffering, and to redress the social and economic injustices that cause that suffering. Marxist cultural theorist Walter Benjamin, Brecht’s contemporary, explains how Brecht’s politics distinguish between simplicity and transparency. Simplicity denotes the defeatist acceptance of misery and resists challenge to the status quo: “That’s just the way it’s always been”; transparency, on the other hand, rejects the mystifications that lead society to believe that suffering is universal and eternal. Erwin Piscator, a Marxist dramaturg who was also contemporary to Brecht, summarizes how tragedy is the result not simply of fate, but of political and socio-economic circumstances:

What are the forces of destiny in our own epoch? What does this generation recognize as the fate which it accepts at its peril, which it must conquer if it is to survive? Economics and politics are our fate, and the result of both is society, the social fabric. And only by taking these three factors into account, either by affirming them or by fighting against them, will we bring our lives into contact with the “historical” aspect of the twentieth century.[6]

In How to Act, the causes of suffering on the African continent, notably in Nigeria, are given clear explanations by Promise. As Brecht highlights in the quotation to which I have already referred, “petroleum” is one of today’s most pressing and complex problems. Promise explains how, in spite of Nigeria’s vast oil wealth, it has been crippled by “debt to western governments and the World Bank.” In addition, she describes how “western oil companies” such as “Shell, Exon, Chevron and Total” have not only made many billions of dollars of profits out of Nigerian oil and gas and massively expanded the west’s consumption of energy and goods while their employees live on “less than a dollar a day”. In addition, these oil companies have committed human rights abuses by encouraging the Nigerian government to execute activists campaigning for social and environmental justice. These perspectives provided by the play engage directly with current geopolitics, since in June 2017 the widows of four of the nine activists extrajudicially executed in 1995 by the Nigerian government for campaigning against environmental damage caused by oil extraction in the Ogoni region of Nigeria, launched a civil case against Shell, accusing them of being complicit in the torture and killings of their husbands.[7] While inheriting from classical tragedy, How to Act conducts, in parallel, a typically Marxist analysis that seeks out the causes for suffering, rather than submitting to them. “[Y]our having everything depends on us having nothing.”, admonishes Promise.

In Theatre & Ethics, Nicholas Ridout defines ethics by posing the question, ‘Can we create a system according to which we will all know how to act?’

[8]

By admitting to the reasons for social, economic, gender and environmental injustices, we can strive towards an ethics of “how to act”, as the title of Eatough’s play suggests.

In some respects How to Act could be described as a postcolonial play, or at least a play that examines and exposes the afterburns of British colonial occupation in Nigeria. The Nigerian playwright and Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, rather than dismissing tragedy outright, argues for the “socio-political question of the viability of a tragic view in a contemporary world”. For him, as he demonstrates in some of his great tragedies, notably Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), the theosophical school which would accept suffering and death as the natural order of things, and the Marxist school which insists that the historical reasons for human suffering must be explored, understood, and rectified, can indeed be encapsulated in the same play (1976: 48). Graham Eatough demonstrates, as Kateb Yacine and Wole Soyinka have done before him, and as authors such as the Lebanese-born Quebecan playwright and director Wajdi Mouawad continue to do today, that tragedy is an enduring form that can not only affirm the inevitability of suffering and injustice, but can also candidly expose the reversible reasons for that suffering. There are economic, social and political reasons for tragic suffering which must be comprehended and apprehended, in order to effect change. These artists replace circles with spirals, and spirals have an end.

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, trans. Shaun Whiteside, London: Penguin, 1993, 37-8.

[2] Roland Barthes, “Pouvoirs de la tragédie antique” [1953], in Ecrits sur le théâtre, Paris: Seuil, 2002, p. 44.

[3] Bertolt Brecht, Brecht on Theatre, trans. John Willett, London: Methuen, 2001, p. 30.

[4] Steiner, George. The Death of Tragedy. London: Faber & Faber, 1961, p. 88.

[5] Kateb Yacine, “Brecht, le théâtre vietnamien : 1958”, Le Poète comme un boxeur : Entretiens 1958-1989, Paris: Seuil, 1994, p. 158, my translation.

[6] Erwin Piscator, The Political Theatre [1929], trans. Hugh Rorrison, London: Methuen, 1980, p. 188.

[7] Rebecca Ratcliffe, Ogoni widows file civil writ accusing Shell of complicity in Nigeria killings, The Guardian, 29 June 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/jun/29/ogoni-widows-file-civil-writ-accusing-shell-of-complicity-in-nigeria-killings.

[8] Nicholas Ridout, Theatre & Ethics, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009, p. 12.

HOW TO ACT Written and directed by Graham Eatough.

Internationally-renowned theatre director Anthony Nicholl has travelled the globe on a life-long quest to discover the true essence of theatre. Today he gives a masterclass. Promise, an aspiring actress, has been hand-picked to participate. What unfolds between them forces Nicholl to question all of his assumptions about his life and art.

https://www.nationaltheatrescotland.com/content/default.asp?page=home_How%20To%20Act

0 notes