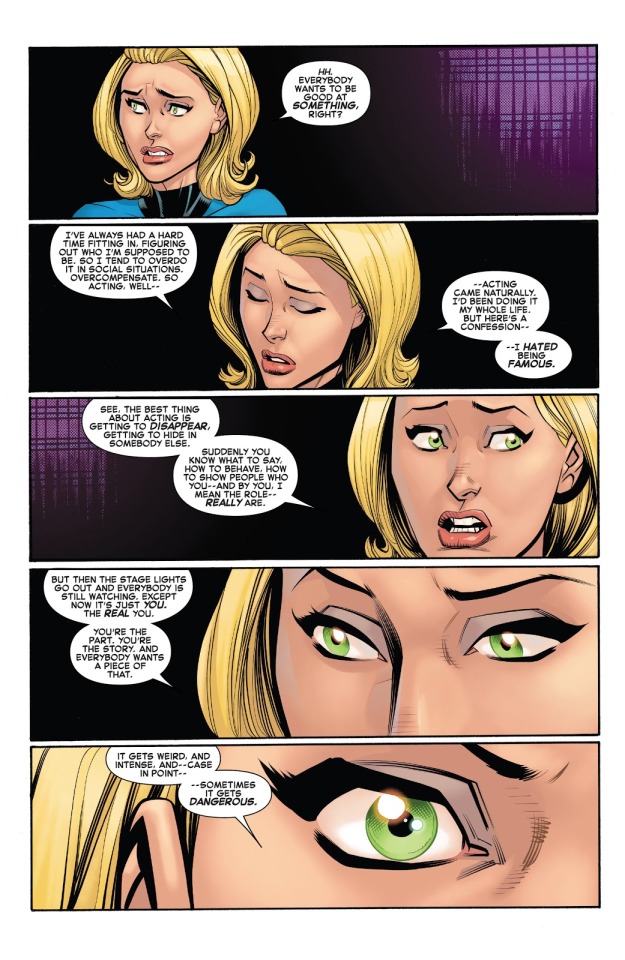

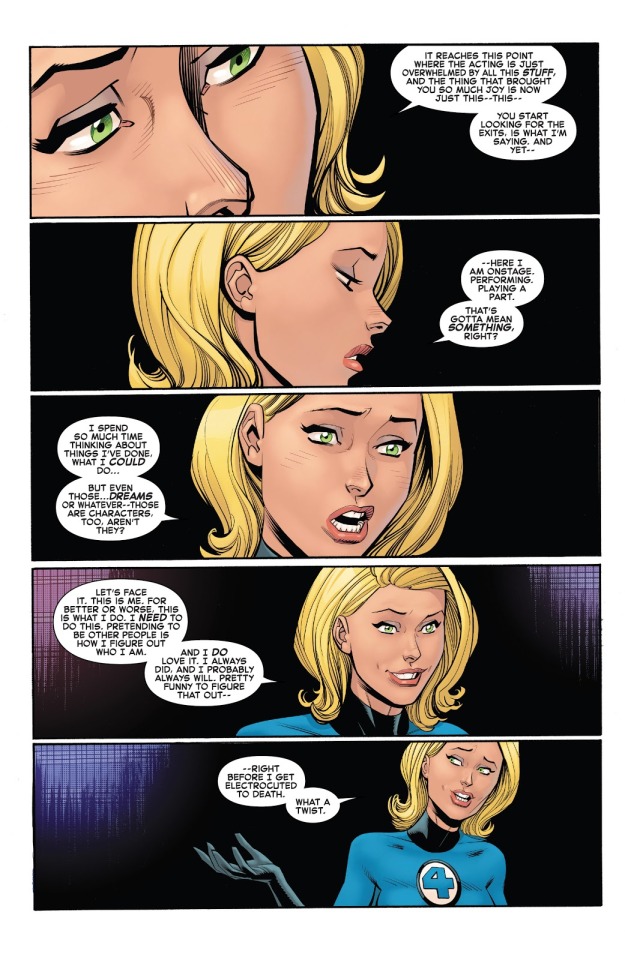

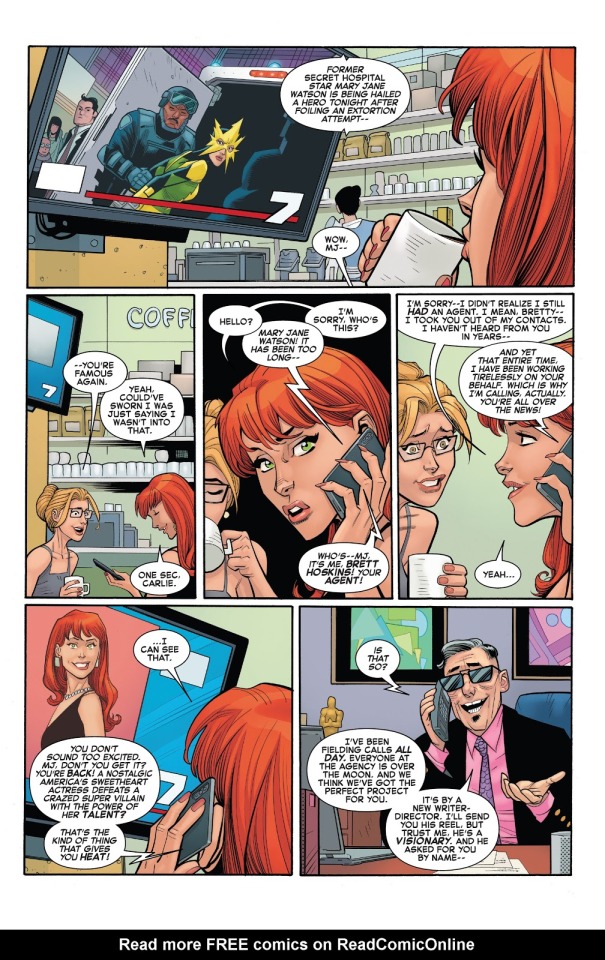

#the last art takes.... so much context for what the director's DOES actually

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hello, I have my little guy, a thirdfrin AU where Siffrin made a wish, but unlike Loop, wasn't as much of a guide. Loop calls him stardust, but he's more aptly named "The Director". Thus, Director AU.

An AU where Siffrin was convinced the loops would never end, that this was always going to be their life forever more, this too sweet existence grating until they feel like they're nothing, he makes another wish.

"I don't want to be here, I can't keep up acting like this, but please give me the power to keep going"

But The Director is not a guide. They are here to ensure that this Siffrin will endure.

Another Siffrin wakes up in the meadow, another try to end these cursed loops. Loop is not as fun of a guide, but they look at this new Siffrin, and calls him our satellite. Loop doesn't play any games, no laughing no fun, the break was lost when stardust decided to give up too. Besides, Loop learned their lesson in trying the same things over and over again and expecting different results. Loop tells them about the keys and refuses to let them leave rooms without taking the ones they would have missed otherwise, makes sure they always go the right directions, all of it.

Perhaps Loop is a good guide, but not much of a friend.

This Loop also doesn't talk with this Siffrin except for the bare minimum. "I'm here to guide you, satellite! Nothing more, nothing less! If you want to talk to someone about the loops, maybe you should talk to your party!"

Loop is a bit more insistent about this whole "tell your party about the loops" thing. Siffrin doesn't get it.

Loop lets Siffrin die to the King; they don't think Siffrin would have believed them if they said he needed a shield. But the dutiful guide tells them of a shield and a secret library. As Siffrin goes to get their needed tools, Loop tries to think of what they can do to make sure their satellite doesn't fall into despair like their stardust did. Because, despite stardust abandoning them, Loop fundamentally believes there is a way out. There HAS to be.

Why would they be here to help otherwise?

Siffrin defeats the King after a few tries. After victory Mirabelle runs ahead. Happily, he guides the rest of the party to the Head Housemaiden and to the end of their journey.

But there's a shout, Mirabelle runs back.

Something is blocking the way. A giant curtain of night as far as the eye can see stretches across the top of the house. There's also a welcome mat sitting oddly on the ground. Everyone tries to read it, but they only get a headache.

Suddenly, the curtain opens, a white glove beckons.

There are two choices, to take it or not.

Curiously, knowing they can just loop if something goes wrong, Siffrin takes it, much to the other's distress.

They're INSTANTLY pulled in. Beyond the curtain, there is nothing but an empty void and a face familiar to their own, but wrong wrong wrong. A star in their stomach, hair of stars, and an incomprehensible shade echoing out from their feet and hair. The being has no eyes to see, but Siffrin knows They Are Looking At Him.

"What are you?" Siffrin asks.

The being opens their mouth and reveals a full row of sharp teeth, made to tear apart and swallow. They speak, but Siffrin cannot hear the words.

The being closes their mouth. And opens it once more.

A single thought echoes and echoes in Siffrin's head.

[GO BACK]

Siffrin.

Loops.

Siffrin wakes up in the meadow.

[Memory of Control] When equipping this memory, your attack speed increases, but you will always do a random attack on your turn.

They immediately go to Loop. Good thing, because the star looks frantic. "I can't see anything past the King, satellite, but I know SOMETHING went down. Now explain."

Siffrin explains what's going on.

And by the end Loop looks on in horror, "oh stardust," they whisper, far too quiet, and almost said without their permission, "what have you done?"

And thus begins their mission to figure out what is going on with this "stardust".

#isat#art tag#luna draws#luna writes#isat spoilers#two hats spoilers#siffrin isat#director au#loop isat#the director#no idea their pronouns tbh tempted to go with 'any'#the director thinks they're helping!!! They are not!!!!#not sure when/if I'll write a fic of this but for now here they are#the last art takes.... so much context for what the director's DOES actually

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

What was it like meeting Val Kilmer? This is probably something that doesn't need asking but I've seen some more things about his bad reputation in the mid/late 90s and I'm just considering the word of someone who actually talked to him.

It was completely lovely. I've gone into a lot of detail about it in a previous post (it's in the last section), but basically it was the best possible experience. He set aside time to meet with me privately so we could have a real conversation one-on-one. He was warm and attentive; he asked me questions and listened when I spoke. When I explained to him how he and his movies had helped me, he seemed genuinely touched, and he thanked me. He gave me gifts, and insisted I get a picture of us together; I didn't even think to ask. I think I was probably literally glowing afterwards.

I've given thought to the rumors of his misbehavior during that period of his life. I'm definitely biased in his favor, but every complaint someone's made against him seems easily explainable given context. The directors of Top Secret! complained that Val asked them too many questions about his character, but this is Val's first major film role. He's the lead. He's only a few years out of Juilliard, which takes the same view of acting that Val did and does: That it's an art. He wants to do a good job; he asks the directors for direction, which is, like, literally their job that they get paid for? idk. Val butted heads with John Frankenheimer, the second director for The Island of Dr. Moreau (and the man who said, after Val wrapped, "Cut! Now get that bastard off my set!" so clearly Frankenheimer wasn't a big fan of Val's, either), but most of his concern seems to be about Frankenheimer not finishing the film. Val had just been informed of his impending divorce via entertainment news in a foreign country, and the first director of Moreau had already dropped out of the picture. Being anxious about partnerships ending and people leaving seems normal given the circumstances. I read a great anecdote from a teamster on The Doors, who had heard a rumor from other crew that Val insisted no one was to look him in the eye or speak to him because he was in character at all times. The teamster ignored this because he was a veteran and had heard his share of weird shit, and one day on set happened to start up a conversation with Val, during which Val asked him, "Hey, do you know why the crew in this city is so unfriendly?" He hadn't even heard the rumor, much less made the edict. And let's be real: It's in the interest of entertainment media to sensationalize things and blow them out of proportion. Drama makes for good TV.

TLDR: I don't worry about it too much. Every personal story I've heard from people I actually know and trust has belied the ugly rumors.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geoffrey Hill – 'The Unconscious Mind's Intelligible Structure': A Debate

I have chosen as title for this brief and inconclusive debate a phrase from Richard Ellmann's Eminent Domain (1967, 52). It is there said of Yeats that to the end, even in his last poems where everything estimable is imperilled, he remained stubbornly loyal to the conscious mind's intelligible structure.' I think it proper to emphasize that I am taking the phrase out of context and employing it in a possibly-arbitrary fashion.

The debate begins, somewhat remotely, by attempting to distinguish between various kinds of objectivity, in the hope that the distinction may profitably be applied to a consideration of modern poetry, particularly that of Yeats. At the outset it is necessary to refer to three epigraphs or texts. The first is from Donald R. Pearce's introduction to his edition of The Senate Speeches of W.B. Yeats (1961):

Mrs Yeats once explained to me that [Yeats] was accustomed to distinguish those pages of manuscript that were to be discarded from those that were to be kept and filed by referring to the latter as 'history'; early drafts of certain poems, abandoned ideas for a play, alternative versions of some essay - all had their place in an intellectual and personal 'history that was as objective to his scrutiny as if it were not his own but the life of another man (p.22).

The second text is a phrase from an essay by Matthew Corrigan, in which he writes of the 'primary objective world... its cruelty and indifference (Encounter, July 1970, 85). The third citation is from Simone Weil:

Simultaneous composition on several planes at once is the law of artistic creation, and wherein, in fact, lies its difficulty. A poet, in the arrangement of words and the choice of each word, must simultaneously bear in mind matters on at least five or six different planes of composition. . .Politics, in their turn, form an art governed by composition. on a multiple plane. (The Need for Roots, translated by AF. Wills, 1952, 207)

One understands Simone Weil to be suggesting that poetry recognizes the primary objective world not so much by exercising its discursive faculty as by enacting a paradigm: a paradigm in which objective... scrutiny', in the Yeatsian sense, is put into the arena with Corrigan's 'primary objective world'. The value of her statement, from one's own point of view, is in her recognition that one does not attain objectivity simply by surrendering to the primary objective world. Corrigan, of course, sees this too. I am employing his phrase for its succinctness, not because I have any quarrel with it. One's debt to Simone Weil is precise. Within the circumference of her 'law', lyric poetry is necessarily dramatic: indeed, the 'different planes' actually available to a director on his theatre-stage could even be regarded as an indication of what takes place 'simultaneously' in the arena of the poem. When Yeats depicts his own search for a speech 'natural and dramatic' (Letters, ed. Wade, 1954, 583), 'simple and passionate' (ib, 668) he is far from advocating spontaneous lyricism. He is, even, in the second instance, possibly echoing Milton. An early use of the word 'passionate in Yeats's Letters is to be found in his reference, in May 1887, to T.M. Healy's 'rugged, passionate speech' in the House of Commons, 'the most human thing I heard. (35). It is arguable that Yeats's sense of 'simple and passionate speech was always forensic rather than domestic.

Yeats recognized himself, though not without irony, to be an artist in the nineteenth century Romantic tradition. This is a self-limiting truism which requires prompt qualification since, on investigation, no such simple entity as the Romantic tradition can be discovered. To make a distinction based on Yeats's own terminology in A Vision, one might suggest that Romanticism had (and has) both false and true masks. The false mask is formed from what Jacques Maritain admirably summarized as the two unnatural principles: the fecundity of money and the finality of the useful (Art and Scholasticism, translated by J.F. Scanlan, 1930, 37). The false mask either gleams amid the fecundity of money or utters, in terms of the finality of the useful, the wrong kind of moral answer. The London commercial theatre, at the turn of the century, flaunting the fecundity of money, aroused Yeats s contempt (Letters, 308–311). He was equally accurate in taking issue with George Bernard Shaw. As early as 1900 (Letters, 335) Yeats was calling Shaw 'reactionary', a particularly prophetic epithet in the light of Major Barbara. It is at least open to suggestion that Shaw's adherence to the finality of the useful, far from being antithetical to the false mask of Romanticism, is but a further manifestation of it. In paying lip-service to the realist, the practical man, Shaw makes the fecundity of money finally useful It is a synthesis of a kind, but such a synthesis as to mak Weil's 'composition on several planes' a preferable alternative.

Having sketched this view of the false mask one will rightly be required to present an image of the true mask. Thus, the 'true mask' could be shaped in one of two ways, each of which is in accord with the conscious mind's intelligible structure The first way presupposes a grammar of assent. The second w: is available if the first is not; and is the way of syntax. Synt: could be understood as Donald Davie presents it in his bor Articulate Energy (1955) or it could be extended to accomodate Simone Weil's 'law of artistic creation', as defined The Need for Roots.

In setting the phrase 'grammar of assent' in lower case ty one is arbitrarily making a metaphor, a metaphor to take place of Newman's reality. A Grammar of Assent is not same thing as a grammar of assent; and one's metaphor exists to acknowledge the difference

As the structure of the universe speaks to us of Him who made it, so the laws of the mind are the expression, not of mere constituted order, but of His will. (John Henry Cardinal Newman, An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent, 1913 ed., 351)

The shape of my debate, if it can be said to have one, require 'mere constituted order' to be held in equal observation against 'the conscious mind's intelligible structure'. It will not have escaped notice that my discussion relies heavily on a law' devised by a writer who, in the words of E.W.F. Tomlin, devoted a good deal of 'wistful attention' to the Church but who was unable, finally, to assent. One is, with the greatest reverence and respect, citing Simone Weil's predicament as being an exemplary one. She has been dead nearly thirty years; the issues have long been public; one is not trespassing on any privacy. It needs to be said equally strongly that one is not trespassing on one's own privacy. There is nothing 'confessional' about this debate. The situation is far from being intimate. Arguably one is describing, albeit hypothetically, a common cultural predicament: so common as to verge on mere truism. One cannot, however, pervert the purity of Newman's meaning. A Grammar of Assent would have to be Catholic: 'Non in dialectica com-placuit Deo salvum facere populum suum'. A grammar of assent, which is a lesser thing, a metaphor, does not have to be Catholic, though it could be:

. . .when faith is informed by what Newman calls real assent, which involves the imagination, it is as living as the imagination itself', and this means to say that it not only leads on to action, but is enriched and deepened by action. (Alexander Dru, Peguy, 1956, 60)

Readers of Alexander Dru's book will recognize that my emphasis does not do his argument justice. I have chosen to interpret as metaphor a statement that he did not necessarily set down as metaphor; and for this I would ask his forgiveness.

It is my contention that there are certain sectors, not necessarily or exclusively Catholic, where real assent, involving a reciprocity between imagination and action, can be observed. There is a sense in which Conrad's assent to the code of the British Merchant Service provided him with a grammar that transfigured syntax as effectively as it transcended dangerous spontaneity. Óne thinks particularly of the two polemic essays, first published in the English Review in 1912, on the sinking of the 'Titanic. His imagination not only leads on' to action but is 'enriched and deepened' by his grasp of right action:

So, once more: continuous bulkheads — a clear way of escape to the deck out of each water-tight compartment. Nothing less. And it specialists, the precious specialists of the sort that builds 'unsinkable ships, tell you that it cannot be done, don't you believe them. It can be done, and they are quite clever enough to do it too. The objections they will raise, however disguised in the solemn mystery of technical phrases, will not be technical, but commercial. (Notes on Life and Letters, 1921, 314)

One notes here how facialties come together: the faculty of moral indignation with the faculty of practical amelioration. Contrasted with this, Arnold's 'sweetness and light' is inane and what Yeats called Burke's 'great melody sounds off-key, reveals itself to be, for all its resonance, a protest against natural right in the name of expediency'. (H.J. Laski, Political Thought in England: from Locke to Bentham, (1920), 1932, 187).

With Burke, however, we approach our second category. Failing a grammar of assent, syntax may serve. Possibly it is not untrue to say that the best answer to Burke's conservatism is to be found in his own pages.' (Laski, 176). In this respect Laski's suggestion conrelates with Arnold's praise of Burke's return... upon himself'. In his essay "The Function of Criticism at the Present Time', Arnold cites the concluding passage of Burke's 'Thoughts on French Affairs' of December 1791:

The evil is stated, in my opinion, as it exists. The remedy must be where power, wisdom and information, I hope, are more united with good intentions than they can be with me. I have done with this subject, I believe, for ever. It has given me many anxious moments for the two last years. If a great change is to be made in human affairs, the minds of men will be fitted to it; the general opinions and feelings will draw that way. Every fear, every hope will forward it; and then they who persist in op. posing this mighty current in human affairs, will appear rather to resist the decrees of Providence itself, than the mere designs of men. They will not be resolute and firm, but perverse and obstinate.

Burke's passage is plangent with futile simplistic determinism and witless platitude (the minds of men will be fitted to it... this mighty current in human affairs). If Burke were spontaneously ejecting platitudes it would be contemptible. It is his very recognition of the force of the contemptible, in oneself and in others, that makes the passage an arena of 'several planes. The fact that such a quality of recognition may be thought uncharacteristic of Burke's general mode does not invalidate its particular power or detract from the effectiveness of Arnold's choice. 'That return of Burke upon himself' says Arnold, has always seemed to me one of the finest things in English literature, or indeed in any literature.' At the moment that one recognizes the justice of Arnold's praise, one simultaneously seizes upon the nub of his situation. Burke's words, which have impinged upon Arnold's critical intelligence in their true nature, that is, as thwarted politics, are made to issue from Arnold's critical intelligence as a quite distinct entity, that is, as English literature'. If, as Alexander Dru suggests, assent in the illative sense 'not only leads on to action, but is enriched and deepened by action', , then Arnold, for all the fineness of his critical eye, is subjecting Burke's sentences to a process of negative conversion. How an intuitive sense of this can oppress a fine intelligence is, I think, nowhere better described than by Arnold himself, brooding over 'Empedocles on Etna':

What then are the situations, from the representation of which, though accurate, no poetical enjoyment can be derived? They are those in which the suffering finds no vent in action... in which there is everything to be endured, nothing to be done. (Preface to Poems, 1853)

If one cannot have a grammar of assent one has a dichotomy. On one side of this will be, at worst, a dependence on tones of voice, Arnold's fastidious whining about an original shortcoming in the more delicate spiritual perceptions'; at best, syntax or 'the conscious mind's intelligible structure. On the other side there may be merely 'manic and depressive phases of activity and inactivity, mostly of an 'intermittent character', as Conor Cruise O'Brien suggests in his essay on Yeats's politics:

If a Marxist, believing that history is going in a given direction, thinks it right to give it a good shove in the way it is going, it is natural enough that one who, like Yeats, feels that it is going in the opposite direction, should accompany it that way with, if not a shove, at least a cautious tilt. (O' Brien, in A.N. Jeffares and K.G.W. Cross, eds., In Excited Reverie, 1965, 263, 265, 278)

Though his phrasing here is callous and slovenly, the critic is not at fault. He knows perfectly well what he is about and his words mimic effectively the nature of Yeats's error: an error which we are to discern amid the shambles of phrases like 'natural enough' and 'if not a shove. In Yeats's poetry there is imagination; in Yeats's politics there is action; but the one does not enrich and deepen the other. There is no real assent; there is no illative sense, no grammar. In politics, therefore, Yeats's aristocratic bias does not save him from vulgarity; the 'aristocrat' is conned by a pseudo-aristocracy of the gutter.

If, however, we accept the dichotomy as a simple datum, we have the right, within the terms of such a proviso, to praise the persistent energy of Yeats's poetic syntax. Arguably, the entire melody of Easter 1916, a poem that Maud Gonne, dedicated to the finality of the useful, thought wholly inadequate to the occasion, is itself an articulation of the Burkean 'return'. So, perhaps, is the second stanza of section five of 'Vacillation', though here one's argument is less secure. Yeats's gesture strikes one as being formulistic:

Things said or done long years ago, Or things I did not do or say But thought that I might say or do, Weigh me down, and not a day But something is recalled, My conscience or my vanity appalled. (Collected Poems, 1950, 284)

The mannerism of lines two and three is close to being a travesty of what Arnold meant when he praised that return of Burke upon himself. Perhaps, though, the last-minute snatching away of the formula constitutes a more genuine 'return'. The last four words of the stanza redeem the truism. One could speak of 'conscience' with firmness and without appearing a fool. It is 'vanity' that, at the last moment, effects the 'return', that concedes the element of clownishness in the man who might have preferred to be a hero in remorse.

It is the final lines of 'The Second Coming that offer what is perhaps the finest of these returns. Scholars have made us familiar with the volatile emotional essences, what one might call the petty romanticism, out of which this major Romantic statement developed. We have learned of the possibly subconscious recollection of Shelley's 'Ozymandias' in Yeats's mental image of a desert and a black Titan' (see Jon Stallworthy, Between the Lines, 22-3) and we have read, in Yeats's own note in Wheels and Butterflies (1934 ed., 103) of a brazen winged beast' that he 'associated with laughing, ecstatic destruction'. I have called such recollections 'petty romanticism'. Yeats made his major discovery in the poem itself, ending:

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born? (C.P., 211)

As far as the original petty vision of laughing ecstatic destruct-ion' is here concerned, Yeats has revoked it, in the energy of imagination needed to recall it. He has returned upon himself and, as in the case of Burke, one would hazard the suggestion that the revocation is the outcome of acute historical intelligence drawing its energy from the struggle with that obtuseness which is the dark side of its own selfhood. In. Yeats's case, however, one does not refer so much to the conceptual intelligence operating through language-as-medium, as to the intelligence activated by the pitch of words. Jon Stallworthy has said (Between the Lines, 1963, 6) that 'where words are concerned [Yeats] has almost perfect pitch'. A poet who possesses such near-perfect pitch is able to sound out his own conceptual, discursive intelligence. The simultaneous bearing in mind described by Simone Weil would here relate to Stallworthy's suggestion about 'pitch. The poet is hearing words in depth and is therefore hearing, or sounding, history and morality in depth. It is as though the very recalcitrance of language - and we know that Yeats found the process of composition arduous - stood for the primary objective world in one of its forms of cruelty and indifference; but also for the cultivation of that other objectivity, won through toil (as objective to his scrutiny as if it were not his own but the life of another man').This is the most rewarding implication to be drawn from the exchange of letters between Yeats and Margot Ruddock. The debate between the old man and the young woman is emblematic, as when Yeats writes in reproof When your technic is sloppy your matter grows second-hand there is no difficulty to force you down under the surface _ difficulty is our plough." To this Margot Ruddock replies Do you know that you have made poetry, my solace and my joy, a bloody grind I hate! . . .poetry should not be worked at.' (R. McHugh, ed., Ah, Sweet Dancer, 1970, 81, 88). The irony is that both Yeats's reproof and Margot Ruddock's retort would have to be construed as belong. ing equally to the Romantic tradition, if such a simple entity did in fact exist. Rather they should each be recognized as an individual gyre within the so-called 'stream' of Romantic think-ing; each of necessity involved with the other and yet radically in conflict.

As I have already suggested in referring to Conor Cruise O'Brien's essay on Yeats's politics, it may sometimes be necessary to mimic a dilemma. At this point in the debate one must suggest, on the one hand, that sincerity is not enough, that creativity means cunning and artifice and that 'spontaneity' is an illusion. On the other hand one may have to concede that social empiricism has made of 'sincerity', especially in its current guise of spontaneous reaction to pressures, a potent arbiter of artistic motive and conduct. Put in its most extreme form, the sincerity of the primary objective world finds utterance in a book by the Polish writer Czeslaw Milosz:

The work of human thought should withstand the test of brutal, naked reality. If it cannot, it is worthless. Probably only those things are worth while which can preserve their validity in the eyes of a man threatened with instant death. A man is lying under machine-gun fire on a street in an embattled city. He looks at the pavement and sees a very amusing sight: the cobblestones are standing upright like the quills of a porcupine. The bullets hitting against their edges displace and tilt them. Such moments in the consciousness of a man judge all poets and philosophers. (The Captive Mind, translated by Jane Zielonko, 1953, 41).

Granted that this is a parable and not a manifesto; even so this passage moves from a first sentence of general acceptability to a third sentence that excludes from acceptability all those unbaptised by an arbitrary fire. The passage purports to establish new terms of the utmost purity: things and moments. What it does, in fact, is to elevate the man-of-the-moment. However humbled one may be by this, it is still necessary not to be bullied by its absolutist élitist tone. For those who detect the élitism, yet remain humiliated by their implied failure to live up to such demands, the poem of rigorous comfort is Yeats's'Easter 1916'. This poem could be described, in Simone Weil's terms, as a 'simultaneous review of several considerations of a very different nature (The Need for Roots, 206). It comprises middle-aged uncertain envy of those possessed by single-minded conviction, together with a humane scepticism about 'excess and romantic abstraction. One is moved by the artifice of the poem, the mastery of syntactical melody, that enacts this tension of 'several considerations'; the tune of a mind distrustful yet envious, mistrusting the abstraction, mistrusting its own mis-trust, drawn half-against its will into the chanting refrain that is both paean and threnos, yet, once drawn, committed utterly to the melody of the refrain. It is not Newman's real assent; it is not what I have chosen to call Arnold's negative conversion; it is certainly not Milosz's 'validity of moments in the con-sciousness. One can say only that it is a paradigm of the hard-won 'sanctity of the intellect (cf. Letters, 525). 'Intellect' is bound to be misunderstood but, in context, it should not be. One is in no way seeking to equate it with 'cerebral'. Yeats claims in A Vision (1962 re-issue, 268):

A civilisation is a struggle to keep self-control

but this poem, in its measure and syntax, stands as his more exact imagining of that struggle and that civility. One may well feel that Yeats presents arguments, or theories, that require to be answered. Yet even when this is so it remains true for him as for Burke: that the best answer is to be found in his own pages.

Published in Agenda, vol. 9/10 (Autumn–Winter 1971/2)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alright, I'm going to attempt to hopefully clear up a few misconceptions and assuage some worries about this Disco Elysium sequel and the general situation at za/um right now.

I see the shitshow that is unfolding on social media, and as someone who has known about this whole disaster for over half a year now I'd like to weigh in on it and provide some context for everyone who may not know the full story.

First off, Robert Kurvitz was fired at the end of last year. December 2021. As is strongly implied on Martin Luiga's twitter, the reason for this is greed (calling them "money men" and "crooks" and other similar statements for like, months now), and the executive producers, Tõnis Haavel (who has previously been tried for fraud) and Kaur Kender (who has previously been tried for... other things.) screwed everyone over. Kender provided funding for the game, as the majority of the original za/um cultural association did not have the financial means to.

The original za/um cultural association consisted of Robert Kurvitz, Jüri Saks, Martin Luiga, and Aleksander Rostov, originally founded in in 2009. The group, along with Argo Tuulik, played many different ttrpg campaigns over the years, several of them set in Revachol (centred around Precinct 41), and slowly built the world up from there. Kurvitz released the book The Sacred and Terrible Air, set 20 years after Disco Elysium, back in 2013* but the novel flopped, and it was decided that they would make a video game. Rostov has always been more than just an artist for Disco Elysium, as you can see from the dev threads he frequently updated promoting the game, as well as on his personal instagram, tumblr sketch blog, and several other accounts he used while the game was first gaining traction.

*The most notable credits for TSaTA are as follows:

Author: Robert Kurvitz, Editor: Martin Luiga, Cover Design: Aleksander Rostov, Worldbuilding: Robert Kurvitz, Martin Luiga, Kaspar Kalvet, Argo Tuulik. Helen Hindpere and Kaur Kender also appear in the credits.

I say this because some of the staff at za/um are now accusing fans of being unable to overcome the "auteur theory" of it all (ie. seeing Kurvitz as the singular creative mind behind it all) but the fact is that they have now lost not only the original ttrpg campaign's game master, The Sacred and Terrible Air's author, and Disco Elysium's lead writer/director (Kurvitz) but also their lead writer for the Final Cut's political vision quests (Hindpere) as well as their "co-founder" and art director/designer (Rostov). They are all CREATIVE LEADS, and not just well known only for their reputations/titles.

Luiga himself (who originally broke the news) was an Elysium world builder and provided much of the pale and innocence-related lore. He was also a part of the original tabletop campaigns (Chester McLaine is his player character!), but left midway through Disco Elysium's development due to creative differences (or as he says, "bad vibes" at the company). He is credited as an editor, but claims to have written a good chunk of the text in the game, including much of Joyce's dialogue about the pale. I have seen people discredit him due to his early departure, but Rostov also tweeted out confirming that he, along with Hindpere and Kurvitz were no longer at the company, with no additional comments. Rostov also posted a drawing on his twitter several months back depicting a man jerking off over an NDA, so take that as you will.

So what does this mean for the future?

Luiga has said that he has hope for the sequel, which could either mean that the script was finished or nearing completion before Kurvitz was fired (likely, and fits a pattern in the industry) and it's just a matter of finishing the actual game development aspect, or it may be that he has hope for the original za/um creatives to be able to re-acquire the IP.

I think it's worth pointing out that the original pitch for "Disco Elysium" was actually "The Return", and Disco Elysium was meant to be the smaller-scale prequel to introduce players to the world. Considering that the team was planning on this sequel all along, I think it's possible that a large amount of the "original" game was written years ago, so it's not all that far fetched to believe that the basic outline may be finished, or even that a large portion of the script already exists. Keep in mind that there are a large number of writers for both Disco Elysium and The Final Cut, and it may still be possible to work with a base that the others provided. We have no idea how far into development the sequel may be. Of course, proceeding without three key members of the original team is kind of a kick in the balls, and imo really quite disgusting, especially with how long the company has been keeping their departures secret (dishonesty is not a good look lmao), but it may still be canon, true to the authors' vision, and genuinely a good game in the end.

Argo Tuulik, original Elysium world builder and part of the old ttrpg campaigns, as well as a main writer on Disco Elysium, is still working at za/um. Justin Keenan, former writer on The Final Cut who wrote the political vision quests alongside Helen Hindpere, still works at za/um (and has been promoted to lead writer, according to his LinkedIn), as does Kaspar Tamsalu, who painted several character portraits, (René and Gaston) and worked as a concept artist on the original game. Plenty of the original creatives still remain. The sequel could very well still be in good hands at the development level, even if the higher ups are "crooked".

So, in conclusion... If this game comes out and they still haven't worked things out with Kurvitz, Rostov and Hindpere? Honestly... fuckin' pirate it. But it is very likely it could still be a great game that plays out as it was meant to! All that being said, FUCK za/um as a company, don't support them through Atelier or their merch store. I wish everyone luck if they do attempt to get the IP back, and I sincerely hope this fan pressure will help get things moving for them.

#disco elysium#ada speaks#if anyone would like sources i can supply them#i just didnt want to bog down the post with links just in case it doesnt show in the tag#im leaving out a lot of shit for Reasons but i hate to see people upset because i do genuinely have hope for the future of elysium#but i will vouch for the quality of the sequel myself.#some minor updates as i accidentally stated argo was part of og za/um

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I think I remember that you guys do voice acting. I was wondering if you have any tips for getting into voice acting, or any tips for someone who's POC specifically who wants to go that route? My friend has been thinking about doing so, and I've been trying to help her out with it so I thought to ask

Huh, ok, so I guess for context, we do this as a hobby! We really could have turned this into paid work (not by joining the big industy, but by charging for lines in general), but figuring out prices has been very weird for us- it's different from charging for art!

I'm going to talk about voice acting at home, not on set/at a studio. We're also more of a character voice actor, s if your friend is looking to go into advertising, narration, etc, our knowledge will be limited on that! But the general idea should be very similar if not the same for some things. (Some companies and businesses or paid work in general will let your record at home, etc.)

We're going to ramble, so I'll put this under a read-more

(Also, a lot of us actually contributed to this post over the last few days, so it’s possible we repeat a few things, or our first-pronouns keep changing. Hope it still makes sense!)

Under the read-more, we’ll talk Equipment, Getting started (Auditions), and Other random advice we threw in.

Equipment

Anyway, you first want to start with your equipment. In our opinion, what matters isn't the name of what you have- but the quality of your end product. If you're recording with an iPhone for example (which is said to have one of the clearest microphones for a phone), that's fine! We knew someone who recorded his lines using his headset microphone. There's this knowledge that headset microphones have really bad quality, and the brand he has is known for being very bad in our country: CDR King, but it was VERY VERY CLEAR.. I remember in voice calls, we'd be at awe with how crisp his voice was! If you're using what you have, just make sure you take care of your equipment- what matters is how it sounds in the end. I will say though, that what's more required of you should be good headphones or earphones, so you can hear what you sound like, you should be able to pick up any mistakes or your background noise (i applicable), the fuzz, etc..

We use Garageband, since it came free with our macbook. I’ve seen a lot of professionals use Adobe Audition. These are not requirements:

Get Audacity. As a voice actor, your job isn't to clean up your lines, but if you're working without professional equipment (AND even if you DO have professional equipment, get Audacity), this really helps with Noise Removal! It's free! You can look up "how to do noise removal in audacity" and there is a lot of information on how to use this thing. For every recording, we put it through Noise Removal in audacity, unless our director specifically tells us not to (we usually ask every director when we meet a new one).

Additionally, you can record in audacity, which is once again free! It makes voice acting so much more accessible to those that can only use what they have

But if you're here to look for microphone and equipment recommendations:

We haven't tried that many Microphones; we've only been voice acting since 2014, and have only had literally 2 microphones over the 8 years! We got our first microphone in maybe 2016, though? When we started taking things seriously, and got a replacement microphone in maybe 2019, which has been our current microphone ever since. I say this, because we might not be the best perspective to suggest microphones from! Stuff's expensive, haha.

Our first microphone was an AT2020 USB by Audio Technica.

In our opinion, it's a good starter microphone. It does it's job, but it's most for talking in our opinion. If you need to sing or scream, it might not be the best, but it did serve us alright. It was a USB microphone, which will not be as good as an XLR. We replaced it because its quality started to degrade (it couldn't handle us screaming). But, Like I said, if you take care of your equipment, everything can last you a long time. We know a fellow voice actor who owns an AT2020 USB right now, and his audio is crisp :-)

Our second microphone, our current one, is a B-2 Pro by Behringer!

We finally got a mic stand so if we start slapping our desk, it doesn't absorb our shock hahaha. The quality is much better, and it can handle us screaming and shouting without the audio clipping. It came with a pop filter that hugged the microphone, and we could switch between different microphone modes! For solo voice acting, you just need it set to taking in audio only from the front side.

Also, when looking for your microphone, I highly suggest doing some personal researches on what ranges microphones can pick up. Some microphones can not handle screaming, while others can. Some microphones are only for talking, some can include singing, some will better pick up lower registers, some can pick up higher voice betters, etc. It’s complicated, but it’s something we looked up because microphones are expensive. And we wanted to make it worth it!

The best microphones will always be XLR's, which means you'll need an audio mixer so you can actually plug it into your computer!

I have nothing to add here, finding the right audio mixer for you depends on your preferences: Do you want every dial possible, so you can adjust the different frequencies in real life and in real time, or are you alright with handling all that in post production (Audacity, garageband, etc.)? With that in mind, do you want a small mixer instead? That will take up less space, and is portable. The only thing you need to worry about is making sure it has a USB output so you can actually plug it into your computer.

The first and only mixer we've ever owned is currently a XENYX Q802 USB. It has a bunch of dials and allows us for more than one XLR plugged in- which we don't need hahaha. It does its job! We just have to replace our microphone wire because you can hear its age now.

Before the pandemic, we were able to try a friend's audio mixer, because we recorded singing for him, and his audio mixer made our recordings so CLEAR without noise removal, but we were using the same microphone. IT WAS CRAZY. It was a Focusrite Scarlet (If you forget the name, searching "scarlet audio mixer" helps. It's a very small thing, and we know two people who own it! Very worth it.

Stepping In To Voice Acting (Auditions)

Like with any acting gig- go to auditions! This may be physical, or online. On Youtube, Twitter, and Tumblr, searching "casting call" and "auditions", then filtering by most recent, should help you! If you like certain medias, you can also type in the name in the search bar. For a huge majority of our voice acting ‘career’. We found casting calls via Youtube.

Otherwise, I highly recommend Casting Call Club, and joining discord servers surrounding casting calls and voice acting :-) For a long time now, we’ve been using CCC and Youtube to look for casting calls, but with Discord now existing, there’s plenty of servers out there. And just the other day, we found a casting call on tumblr!

Other Stuff (We throw random advice)

After that, the rest is just taking care of your responsibilities as a voice actor. Be on time, and respond to messages!

Unfortunately, we can’t give advice on how to price your work, we don’t have enough experience on that. but as usual, don’t go below minimum wage unless you’re totally fine with that. This is a service work, so just like how physical actors will have varied prices, it depends on your reputation and experience.

Editing your audio is literally not supposed to be your priority, unless you want to do that and it’s something you’d prefer than have someone else edit. If anything, the most I would suggest any voice actor do, is noise removal; But you shouldn’t be adding your own reverbs and echo’s unless, once again, you’re alright with that. I say this, because a voice actor’s job is to come in with your lines, give good takes, and leave. Just because you’re able to record at home, doesn’t mean you should be doing literally all the other work for every single project. That’s your director’s problem, unless you offer it

Don’t record more than 3-5 takes per line or paragraph. It will give the editor a headache, and it’s useless if all 5 takes will sound the same, anyway. What we do, is that after we finish recording a whole session, we go to audacity for noise removal. While we do that, we also listen through the whole recording to remove any useless takes to keep things quick and precise. this is Extra work, but a personal choice so we can look more professional and to-the-point.

If you need to scream for the line, then scream! Whisper screaming does nothing. Voice acting is not just saying the lines just because; you still have to be in character.

It’s ok if you’re not friends with the director or other cast members. It’s never an obligation for you to hang out in the cast servers. if you feel like you’re being forced to participate in a project server, that’s personally a red flag. You are allowed to say no to roles or events, this is especially if you are doing this as a hobby, or for free.

Voice acting needs you to be unafraid to be silly and goofy. Even if you’re introverted outside of the booth, you need to be able to show as much emotion with your voice when called for it! Allowing yourself to let loose means you can act for almost any role.

Speaking of the above, find out what you can do, and run with it. While we do original voices for characters of original works or creations, we actually started out with doing impressions of MLP Characters. To shorten the story, we’ve always wanted to play Fluttershy roles growing up, but the Fluttershy role is honestly oversaturated with voice actors who aren’t always the most accurate. Turns out, we’re extremely good at Twilight Sparkle, but originally never wanted to voice her. Thing is, No one ever voices Twilight Sparkle, it’s surprisingly in-demand since no one can do her much. Obabscribbler described us recently as one of the best Twilights out there. Even right up there with IMShadow :-). If you find your niche, it’s ok to run with it, even if you never originally planned to do that. Maybe something you never liked originally doing, was something plenty of other people of needed.

But if you feel stuck, practicing outside of your comfort zone will always be the best recommendation.

Lastly, take care of your voice! If you feel a sore throat coming on or a cold, immediately get as much rest. Your voice box is your tool, and you will be out of commission literally until you fully recover.

Also, I just realized that we didn’t include any advice for POC.. We’re Asian (Filipino), and I unfortunately don’t have a lot to add. I suppose this is because as a voice actor, you’re behind a curtain so no one will see you or your skin and features. I will say though- you can make it as a voice actor no matter who you are or what you look. As long as you’re a decent person, you can go anywhere and do anything. What matters, as a voice actor, is your skill. I say this as someone who voice acts at home, and does not go to physical auditions where people can see my face.

Your luck may especially come from those who are specifically looking for voice actors of color. If you want, looking for characters that have your ethnicity or accent might be something you’d be interested in! We personally just go after characters we want to voice, and it’s just a bonus if our ethnicity and background might match the character :-) (See: we voice a lot of non-humans haha). After all, you are supposed to be the character, unless the character was specifically molded after you. The different voice acting communities we’ve been in have been extremely diverse! The world is truly your oyster

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film Details #1: The Stairs in The Red Shoes

Film Details is a blog series of posts focusing on a specific detail in a film. Details may vary from a single shot, a particular cut, or a piece of sound to individual scenes, objects, and other elements in mise-en-scène as well as larger-scale motifs in the film under scrutiny.

One of the most memorable shots of The Red Shoes (1948), a mesmerizing classic of fable and ballet cinema, is actually a subtle combination of two identical shots by means of an almost unnoticeable jump cut. It is the image of Moira Shearer’s legs as she is rapidly running down a narrow spiral staircase. The shots are in a fairly small scale and framed in a manner that crops the rest of the character’s body so that attention is distinctly placed on the radiant red shoes on Shearer’s feet. Yet the background, or not just a simple backdrop of course but a space in which this event occurs, is also important: the staircase. Director Michael Powell has explained how he achieved the trick together with his crew. In order to capture the quickly moving legs of the actress, they had to first commission a separate spiral staircase to be moved and filmed, then make a rotating mount underneath the staircase so that they were able to move the spiral staircase in synchronization with the downward movement of the camera on the crane without losing the actress behind the edges of the staircase [1]. The impression is impeccable and alluring. There is an enigmatic sense of movement that feels impossible in a way that strangely resembles the viewing experience of a similarly enchanting, though very different, trick shot of a staircase in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). What should draw specific attention to the staircase at this crucial moment in The Red Shoes, however, is that this is not the first instance of the in-between space of transition in the film. There are plenty of steps along the way.

Before compiling, analyzing, and interpreting the many stairs of The Red Shoes, it is important to provide a short reminder of the film’s basic story line. It is crucial to bear this in mind because it is the story and the characters’ core relationships that introduce the film’s key theme that is articulated and structured by the staircase motif.

The Red Shoes is a film about the conflicts of life and art. It tells the story of a young aspiring dancer Vicky Page, played by Shearer, who is hired by Boris Lermontov, played by Anton Walbrook, to his renowned ballet company. During the time that Vicky is hired, Lermontov also employs an up-and-coming composer named Julian Craster, played by Marius Goring. Together they achieve great success, both creatively and financially, when Lermontov produces a ballet based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy-tale The Red Shoes, starring Vicky and with music composed by Julian. To much of Lermontov’s disappointment, however, since he sees other matters besides art as destructive to the creative enterprise, Julian and Vicky end up falling in love. Lermontov fires both of them in hopes that Vicky would leave romantic love behind and come back to the lure of the red shoes and ballet, as she eventually does. Yet, Vicky remains torn between the two men, who represent her conflicting desires for love and art, and in the end dies by falling under a train. She is, just like the protagonist in Andersen’s fairy-tale, unable to take off her red shoes; she is incapable of shaking off her pernicious passion for art. The story is rather simple, but it is elevated by a cleverly treated intertext of the Andersen story. The theme is as old as mankind, but Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger craft a unique cinematic discourse to articulate the theme and give it new meaning. Even more so, the film is rife with details that have this very effect. The staircase motif is one of them.

There is a plethora of stairs in the film. There are the stairs on the balcony to which Vicky runs and from which she falls to her death after leaving the rapid plunge to the spiral staircase behind. These steps on the balcony (and not the spiral staircase) are in fact the real last stairs of the film. More towards the beginning of the film, there are also the almost off-screen stairs leading to the party held by Vicky’s aunt in hopes of attracting Lermontov’s interest in her niece who is an aspiring dancer. There are the behind-the-scenes stairs leading to the stage at Covent Garden where Julian goes to after Lermontov has hired him for Ballet Lermontov. There are the further steps Julian climbs with Irina Boronskaja, the leading dancer of Ballet Lermontov who eventually leaves the company due to her marriage (exemplifying what Lermontov fears for Vicky). There are the stairs behind the stage which the dancers, including Vicky, walk down after the first class is dismissed. More towards the end, there is an underground staircase which leads to a platform at a railway station which Lermontov climbs to reach his train only to discover Vicky trying to convince him that there is room for more in her life than just dancing.

All these scenes concern, more or less explicitly, a movement between the outside world of real life and the dream world of art. I shall flesh out this interpretation in more detail below. It is perhaps more direct in scenes where characters move through stairs to the stage or away from the stage and it is perhaps less explicit in scenes such as Lermontov’s arrival to Vicky’s aunt’s party or his arrival to the train platform. But it is there, nonetheless: Lermontov’s confident walk on the stairs precedes Vicky’s attempt to reconcile the conflict; she tries to make Lermontov agree to let her dance as well as live her love life.

However, one scene not mentioned above is especially characteristic of this thematic function of the staircase motif. During the first day that Vicky and Julian are working for Ballet Lermontov, Lermontov climbs the small stairs of the theater from the auditorium to the stage. This moment, though seemingly minute especially when considered in the context of the staircase motif, is revealing in terms of the thematic function of the stairs in the film. In the long take, Lermontov first passes Julian trying to reach him in the auditorium and then Vicky trying to contact him on the stage. Lermontov moves from the shadows, that is, the real world, to the limelight of the stage, the dream world of art. It is this movement between these two worlds that is reflected by the many stairs of The Red Shoes.

All the stairs mentioned above are quite minor. That is to say, one does not really pay attention to them unless one is specifically looking for them. Even the thematic function just outlined might seem a little vague at first. But it becomes more salient, I believe, when one looks at these instances in the broader context of the staircase motif with its most important manifestation. To be more specific, there are three scenes in The Red Shoes in which stairs gain increased significance: there are the entrance stairs of Covent Garden in the beginning, the stairs of a castle-like building in the middle, and the stairs in the end (the spiral staircase and the stairs on the balcony). Since I have already described the final scene with the spiral staircase and the stairs on the balcony, I will start by describing the beginning and middle scenes both of which have not been mentioned above.

The stairs in the beginning are actually the first thing that are seen in the film. The film begins with a low-angle shot of a staircase leading up. Off-screen noise of a crowd from the outside is heard on the soundtrack. A porter enters the screen space at the top of the stairs and walks down a few steps. A cut reveals two guards holding the door shut below the staircase. The porter tells them to open the doors and let the awaiting crowd in. The crowd is a group of excited students about to lose it over ballet. It is opening night for Ballet Lermontov at Covent Garden. The camera follows the intense running of the students through the stairs until it settles on a corner to capture their enthusiastic movement -- which even ends up tearing a Ballet Lermontov poster for the show on the wall. The real world that is left behind is tactile, palpable, whereas the world of art is anything but. The audience is there to sit still; they are there to see and to hear, as they very clearly emphasize in dialogue with each other. It is this opening scene that establishes the theme of movement between the two worlds through the staircase motif.

Between the scene with the stairs in the beginning and the scene with the stairs in the end (both the spiral staircase and the stairs on the balcony), there is appropriately another chief scene involving stairs in the middle of the film. It is the scene where Vicky, all dressed up in a beautiful blue dress with an adorable tiara, accentuating her red hair in glorious Technicolor, is summoned by Lermontov to attend his company in an eerie castle-like building straight from the pages of a fairy-tale. Arriving to the scene, she climbs a stairway only to find a massive set of steps covered in grass. At the top, there are more stairs to be climbed. And what awaits her after all these steps? Lermontov telling her that she will be cast in the lead role for his new ballet based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy-tale The Red Shoes. The length of passage from the ground to the higher top where Lermontov awaits seems to reflect the hardship that entrance to the life of art takes. At the same time, however, the duration of the journey to the top expresses the detachment of the world of art from the real world below. Furthermore, the long stairway covered in grass has a mystery to it, enhancing the transition to the dream world of art. It is as if the film took a momentary pause to emphasize not only the narrative importance of this turning point but also the enchantment of art, which is both alluring and horrific.

As said, the stairs in these three scenes are more noticeable. They articulate, perhaps more explicitly, the theme of movement between the real world and the dream world of art. In the opening scene, excited students rush the stairs, leaving the tactile real world behind, to get closer to the dream. Julian Craster, the composer who Lermontov eventually hires for his company and with whom Vicky ends up falling in love, sits on the balcony, listening to the music. Vicky, however, is closer to the stage; she is already enamored, perhaps too enamored, with the dream world of art. She is the one to tell Lermontov that the way others justify continuing to live is how she justifies dancing. To her, the raison d’être for human existence is equivalent with the raison d’être for dancing. And, of course, she is the one who ends up dying for it. In the scene mentioned just above, the scene where Vicky walks up the high stairs of the castle-like building to hear Lermontov’s life-changing announcement, there is a similar sense of inter-world movement. Vicky is dressed as a princess, not for this occasion that has come as a surprise to her; she climbs the stairs covered in grass to a castle; she learns that she will be starring in a ballet based on a fable. The fairy-tale connotation could not be more unambiguous. The real world is left behind as the character is elevated (also concretely via the long stairs) to a spiritual plane of art. The fairy-tale aesthetics are used to further highlight the detachment of the world of art from the real world, a detachment that is, as said, both seductive and frightening.

In both of these scenes, characters move closer to the realm of art. In contrast to them, the famous image of Vicky rapidly running down the spiral staircase conveys an opposite kind of movement. This is not just to point to the simple fact that people are running or walking up in the first beginning and middle scenes, whereas Vicky is running down in the last scene, but to make a metaphorical observation about these kinds of movement. In a word, Vicky’s rapid run is her fleeing the dream (her dream) rather than getting closer to it. Following the scene where she is practically torn apart by Lermontov and Julian, the former embodying the dream world of art and the latter the real world with romantic relationships, Vicky is struck by a feeling of horror as she wobbles toward the stage escorted by her dresser. She -- perhaps controlled by the red shoes like the girl in the Andersen story -- starts to withdraw. She rushes away and storms to the spiral staircase. The image of her legs racing the stairs represents her fear, her uncontrollable need, and her conflicted desire to get farther away from the dream world of art that means everything to her, but also, in the same breath, her conflicted desire not to leave the art world that has started to consume her. The ambiguity of what is in fact happening in this finale (is it Vicky’s own free will or the spell of the red shoes? Is Vicky running away back to her love or is she running to her death?) emphasizes the unresolved conflict of art and life that torments the protagonist.

What is striking about the spiral staircase in contrast to the other stairs in the film is its surreal dimension. When one sees stairs in the film, one is quite sure of their location and spatial relation to the other spaces. This is not surprising at all because stairs are precisely a connection link between two or more spaces, typically between floors. There can be clear visual cues such as an arrow sign and the word “stage” on the wall reminding us where the stairs are leading or cuts from previous scenes to subsequent scenes that provide spatial context for the stairs. Such is the case, for example, with the scene where Vicky is training with the other dancers of the company. The scene ends with the choreographer shouting “class dismissed!” A cut shifts us to the behind-the-stage stairs which Vicky climbs down (see the image above). One can see the word “stage” on the wall in the background. The camera follows Vicky as she moves farther away from the stage until the camera stops at the music rehearsal room where the next cut shifts us. For another example, take the scene with the castle-like building. A cab driver picks Vicky up from the hotel. A long drive takes her to an unknown destination, but shots of the beautiful natural environment give the spectator a spatially coherent sense of the journey. After the drive, Vicky is then seen at the beginning of the first stairway which she starts climbing; next, a cut to movement shifts us to her arriving to the top of these stairs where she opens a gate, in a mobile following shot, to the huge flight of stairs covered in grass. Finally, a dissolve shows her arriving to the top of yet another staircase, which eventually leads her to Lermontov. In both scenes, the spatial relations are very clear. No such cues are available for the image of the spiral staircase.

After the shot of Vicky running away in fear, there is a cut to the conductor of the orchestra starting The Red Shoes ballet. The next cuts shifts us to the spiral staircase whose exact location in the building remains a mystery. The following cut does not help provide context for the spatial relations either: the camera remains on Vicky’s legs in the red shoes, with the rest of her body cropped off, walking an unknown hallway and climbing down a few steps until she arrives to the stairs on the balcony which lead to the more familiar space of the balcony over the railway tracks. In addition to the shots preceding and following the two combined shots of the spiral staircase, the shots of the spiral staircase themselves further enhance the spatial ambiguity. Given the velocity of Vicky’s flee and the duration of the two shots, one would assume that the spiral staircase covered quite a long journey. It is hard to see where exactly in the building such a large spiral staircase would be located. It is possible, of course, but it is not clear by any means. It is a surprise to the spectator, and that surprise is precisely the point.

More important than the shots surrounding the image of the run in the spiral staircase is, of course, the overall uncanny impression of the image of the spiral staircase itself. By combining the fast movement of the actress with the synchronized movement of the camera as well as the unnoticeable movement of the spiral staircase, the image gains a totally unique sensation that is quite difficult to be put into words. The fact that the actual staircase in the physical space (of the studio setting) has been moved with the help of a rotating mount while filming enables the camera to capture the actress’ movement in a different way than it would had the staircase remained still. However, since the staircase does not move in the diegetic space (i.e., the space of the fictional world where the characters act), the visual impression is perplexing to say the least. This only highlights the surprise factor of the cut to the spiral staircase. The surrealism of the image emphasizes that the protagonist’s flee is not really physical or concrete but metaphorical. In the poetic space of the film, the character is detaching from the dream world of art that means everything to her -- from the world whose detachment from reality had been established at the latest with the fable-like stairs covered in grass. The unresolved conflict can only end in death.

In addition to the thematic trajectory outlined by these three scenes (first steps toward the world of art at Covent Garden in the beginning, then entrance to that world via the stairs covered in grass in the middle, and finally an escape from its consumption of the soul in the spiral staircase in the end), it is worth noting that the famous seventeen minute ballet sequence of the film also features stairs. That is, stairs are involved significantly in the production design of not only Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes but also in The Red Shoes by Ballet Lermontov. There is a staircase in the background of the main milieu of the ballet, which is first being walked up and down by two women. In the end, the girl with the red shoes, played by Vicky, collapses on the stairs after being exhausted by the red shoes. Having been released from the curse of the red shoes by death, Vicky’s body is finally being carried by a man toward the stairs.

Although these uses of the staircase motif take place in a story within the story (the Andersen story as a ballet performed by characters in the film), it is quite interesting that stairs appear in the beginning and the end of the ballet, just as in the film itself. Stairs in the ballet also connote transition and, specifically, death. It is as if the stairs, which in the first instance are associated with entrance and movement, eventually turned into a gateway between two worlds. Vicky is first brought to the world of art (the first instance of the stairs in the ballet), then dies for it, and is finally being taken away from it back to reality (the last instance of the stairs in the ballet). This affinity between the ballet and the film should not come as a surprise, of course. For the ballet, to a very large extent, reflects many of the events in the film, including Vicky’s budding conflict between Julian and Lermontov.

The staircase is an in-between space between spaces. Movement in the staircase thus usually connotes transition. Here, I have claimed that the stairs in The Red Shoes operate as a metaphor for the characters’ (mainly Vicky’s) movement between the real world of life and the dream world of art. The movement is oftentimes casual, but even then it exemplifies this thematic function. In scenes where the movement is less casual and the staircase is more salient, that is, the three scenes in the beginning, middle, and end discussed above, the articulation and structuring of this theme is more conspicuous. Vicky is first pulled toward the dream world of art by its mysterious lure in the first and second of these scenes, which establish the detachment of the dream world of art from reality, but in the end she is almost pushed away from the dream world by its even horrific enchantment with which she once identified so strongly. In the astonishing shots of the spiral staircase, the link between the worlds has broken down, which is reflected by the eerie movement in the shots and the ambiguity of the relations to other spaces. The image is a shock. The extraordinary effect of the image of the run through the spiral staircase, a spatial link both displaced and uncanny, expresses this ambiguous and unresolved conflict of art and life in the life of an artist.

Notes:

[1] Michael Powell tells this anecdote to Peter von Bagh at the Midnight Sun Film Festival in 1987: “At the end of the film, when the girl runs to her death in the red shoes, she gets out from her dressing room. I thought that it would be terribly boring if she just ran the stairs down in an ordinary way so I had a spiral staircase of roughly six meters made for the scene, the likes of which are used in industrial facilities. I asked Moira if she could run down the stairs in her ballet shoes. She told me she could. The camera had to shoot the running from a descending crane. I asked Moira to run as fast as she could because I wanted the shot to be as short as possible. I gave Moira the signal to go, and she ran the stairs down faster than the camera was able to follow. She beat the camera by roughly 20 film frames. The cinematographers were ashamed. She had to run again, and this time the camera kept up with her, but when Moira ran the spiral staircase, she was of course momentarily concealed by the staircase for every lap. Since the camera was unable to turn around the staircase in the same speed, we had to have a rotating mount made for the staircase whose speed could be controlled so that Moira was constantly kept in front of the camera. We told Moira that now she could run as fast as she wanted. She ran and won the camera again by two seconds. Later, once we had the shot, my editor Reggie Mills asked me if we could lengthen the stairs. I answered no, unless we would get a new staircase. But the shot was too short as it was so we decided to develop it twice and then cut the pieces together so that it would look like one shot.” (Peter von Bagh, Sodankylä ikuisesti [Sodankylä Forever], WSOY, 2010, p. 55; my translation from the Finnish text.)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monster Hunter Rating 21: Khezu, the Blank Stare

When I reviewed Basarios, I made a joke about how the devs likely gave it human teeth over sharp teeth because the latter might not give children nightmares, but I don’t actually think that the devs ever intended Basarios to be more terrifying than any other monster in the game. This monster, however, is literally the stuff of nightmares, and I’m not misusing “literally” here. This may be the longest review I’ve written yet, so buckle up. Time to get spooky with Khezu!

(How it appears in Monster Hunter 1)

(How it appears in Monster Hunter Rise)

Appearance: I think there’s been a mistake here; last I checked, Capcom wasn’t making Silent Hill games. Seriously, this thing would fit right into that series, and not just ‘cause its phallic neck lends itself well to metaphors. The pale, veiny skin, the leech-like mouth, the complete lack of eyes...Khezu’s unlike any other monster in the series because it’s the only monster that’s meant to be horrifying to look at. It’s got flabby, tattered wings and gecko-like feet, but its main characteristic (other than the head) is its tail, the tip of which can open up into a suction cup that allows Khezu to stick to ceilings.

Obviously, Khezu’s an abomination that came from a really dark place in someone’s mind, but that’s just it: Khezu is a monster that appeared in an MH developer’s nightmare either before or during the production of the first Monster Hunter game, and said developer (I don’t actually remember who) decided to put it in the game. I learned of this from the Twitch streams of a streamer called DuncanCan’tDie, who’s a huge MH fan that’s on great terms with Capcom. Unfortunately, I can’t find any other sources for this claim, but I don’t think he’s lying for a few reasons; firstly, like I said, he’s on great terms with Capcom. He’s friends with some people who work there, and he even has a tattoo designed by someone on the MH team he called “Kaname-san” (who didn’t actually give him the tattoo, but drew the design that a tattoo artist used) and the only person who could go by that name is Kaname Fujioka, the man who literally directed several MH games, including the first one, and who was the art director for Monster Hunter World. So yeah. Duncan and Capcom get along great, and if he was spreading false rumors, they’d probably know about it.

The second reason I believe Duncan about Khezu’s origin is that someone once came into one of his streams (and I was there at the time) and started spouting “lore” about two monsters that looked like they could be related, but actually weren’t. Duncan flat out told this person that what they were claiming wasn’t mentioned anywhere and asked for sources...which the loregiver did not provide. In fact, after Duncan started getting on their case, I don’t think they said a word for the rest of the stream. Duncan believes that this person was just making stuff up to sound like they knew a lot about MH and weren’t aware that he was an MH expert, and I doubt that someone who would call someone out on that would do the same thing, especially if he had a reputation to uphold.

I apologize if I spent a lot of time talking about that, but I didn’t want people getting on my case because they couldn’t find anything to support my claims. But in conclusion, I believe that Khezu truly was born of a nightmare, and that’s awesome. It makes the Silent Hill comparison even more fitting since the enemies in those games are basically projections of the protagonists’ psyches. Disturbing enemies are much more effective if they scare(d) the people who created them, and Khezu is certainly disturbing. Because of that, as well as its ominous origin, I’m giving it a 9/10.

Behavior: Khezu mostly inhabit caves, jungles, and swamps due to the need for their skin to be moisturized, though they usually only leave caves to hunt, which they don’t have to do very often due to the plentiful fat beneath their skin, which also keeps them warm. Their favorite hunting strategy is to ambush their prey from a location usually concealed by darkness, which is made easier by their extendable necks. However, their reliance on darkness, as well as their preference to dwell in caves, has made them completely blind and reliant on their other senses; despite not having visible nostrils or ears, Khezu have great hearing and a very good sense of smell. Back to hunting, while they need to subdue larger prey, smaller ones, like Kelbi, are slowly swallowed whole...which is apparently something you can actually witness in the games, according to TV Tropes (I normally stick to the wiki and what I already know for resources, but I went to the “Monster Hunter / Nightmare Fuel” page while searching for another source for Khezu’s origin as a nightmare). As if this thing needed to be more disturbing, it doesn’t always kill its prey before it tries to swallow it, so the Kelbi you can see it eat is constantly struggling as the Khezu swallows it bottom-first. That’s...that’s messed up. But it gets worse.

Practically every monster in this series isn’t any more intelligent than what we consider a normal animal to be. Aside from Lynians, which are people, the smartest monster I’ve talked about is the Velociprey, which might not be as smart as, say, an irl crow, which is very intelligent by the standards of nonhuman animals. What I’m getting at here is that most of the monsters in this series don’t really take any sadistic pleasure in killing and eating prey; they just do it to survive. But Khezu is different. In several MH games, including Rise, the first time you go on a quest to kill a specific monster, the gameplay is preceded by a cutscene that shows off how powerful or intimidating that monster is (and in Rise’s case, you also get a poem). Here’s Khezu’s intro, and I want you to pay attention to what Khezu does from 0:24-0:30:

youtube

That’s right: this thing��“looked” right at the monster it was going to eat, and smiled. That isn’t just me anthropomorphizing it, either; I’ve seen what Khezu looks like outside of that cutscene, and even with its mouth closed it has a neutral expression, so it smiling actually means something, and considering the context, it’s obvious what the devs wanted us to take from it: Khezu likes killing. It enjoyed the prospect of swallowing that monster whole while it was still alive and struggling, which means that this is the first monster I’ve talked about that we can definitively say is evil rather than just an animal. Rather fitting for a living nightmare, I would say. And if you thought all that was disturbing, I have some...unfortunate news. I hope you aren’t eating anything right now, ‘cause this next part is just gross.

Y’know how some wasps lay their eggs inside other bugs so the eggs have incubation they can eat when they hatch? Well, uh...Khezu do that, too. And they’re hermaphrodites that, from what I can gather, don’t need to mate, so any adult Khezu is capable of injecting another monster with its “whelps” (not saying that Khezu are always “pregnant,” just saying that any of them can be). And you know the really crazy part? After everything I said about Khezu, there are still people in the MH world that tame them and keep them as pets. Why would you want to have a slimy, flabby, sadistic, parasitoid, 14-to-40-foot abomination as a pet!? God, people are so freaking weird.