#the first one looks idyllic but in essence it's all deception

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

THE DOUBLE 墨雨云间 (2024) Two different men, two very different embraces...

#the double#the double 2024#the double the series#usersugar#userrobin#dailyflicks#userrlaura#userlera#useraurore#asiandramanet#asiandramasource#tvedit#userbbelcher#chewieblog#perioddramaedit#weloveperioddrama#usermandie#userkitkat#dailyasiandramas#cdramaedit#cdrama#baek1nho#wu jinyan#wang xingyue#episode 9#episode 14#it's about the contrast! it's also about the contrast in colors!!!#the first one looks idyllic but in essence it's all deception#but the second one is more sincere - he's comforting after a scary situation and she needs that hug#also you would never guess that the one in white is her husband who betrayed her in the worst possible way

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Depending on who you ask, the character of Tom Ripley is a Machiavellian criminal, a mastermind of deception, or a hopelessly deluded dreamer. Patricia Highsmith’s quintet of novels centering on the tortured, talented con artist have invited several cinematic interpretations, each with a different take on his slippery essence. Some actors might hesitate to step into the protagonist’s dubiously-acquired Ferragamo loafers, but Andrew Scott, star of the new limited series Ripley, had no such qualms. “Since I’ve been associated with the role, people say ‘Oh my god, that character,’” recalls the Irish actor, known for his subtle, precisely observed performances as the magnetic Priest in Fleabag and Adam, a lonely writer batting grief in All of Us Strangers. “People have a lot of preconceptions about Tom Ripley. It’s my job in some ways to ignore all that and create our own particular version of it.”

Anchored by Scott’s mercurial performance, Ripley is a finely drawn character study of one of the most beguiling creations of twentieth-century fiction. Helmed by DGA Award-winning director and Academy Award-winning writer Steven Zaillian, the gripping psychological thriller unspools over eight episodes shot in elegant black and white by Academy Award winner Robert Elswit. From a rat-infested flophouse in 60s Manhattan to a dolce vita gone sour in Italy, Ripley’s travels — and travails — come to life in noir at its most luxurious and complex. Its cinematographic lushness is haunted by ever-present threats of deception and violence and shot through with sly wit. “It’s just the way I write, intertwining drama and in this case, suspense, with humor, because that’s what life is like,” says Zaillian. “I’m always after what’s real in behavior.”

When we first meet Ripley, he is scraping together a living in New York’s underbelly when an offer arrives that few in his position would refuse. A shipbuilding magnate practically hands Ripley a blank check to retrieve his wayward son Dickie Greenleaf (Johnny Flynn) from an extended vacation in Italy. Yet upon arrival, the mission takes on a complex and sinister edge as Ripley becomes dangerously infatuated with Dickie’s haute bohemian lifestyle and carefree cool. He grows possessive and jealous, raising the suspicions of his partner Marge Sherwood, played by Dakota Fanning. “Marge susses him out pretty quickly,” notes Fanning. “A lot of the other characters think that they’re playing Tom — and Tom is fully playing them.”

Zaillian sought out Fanning after watching her “expressive and eerie” turn as the Manson cult member Squeaky Fromme in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood: “I thought, This is someone who can go toe to toe with Tom Ripley, who is too smart to be conned, who can threaten his schemes.”

To find the perfect setting for Dickie and Marge’s Italian idyll, Zaillian and production designer David Gropman set about the rather enviable task of location scouting on the Amalfi coast. Amid the area’s swishy modern-day hotels and luxury boutiques, they discovered Atrani, a quaint village that seemed frozen in time with its lemon tree-lined streets, tenth-century church, and stunning vistas of the Tyrrhenian Sea. The costume department meticulously recreated the period’s fashions to outfit a supporting cast that brings richness to Atrani’s pensiones and vibrant life to its bustling Roman piazzas. Filming happened to coincide with a lull in vacationers, adding to the authentic feel. “This was during COVID, so there were no tourists,” notes Zaillian. “It made it feel all the more like we’d gone back in time.”

Despite its fidelity to the 60s setting, there’s a sense that Ripley is meeting the moment, reentering popular consciousness at a time of cultural fascination with real-life scammers such as Anna Delvey and Elizabeth Holmes. Even so, Scott bristles at the idea that the series’ protagonist is a mere grifter. “I think he’s very charming and not in a manipulative way,” says Scott, who rocketed to stardom playing a true literary villain, James Moriarty in the BBC’s Sherlock. “When [Ripley] comes to Italy and he’s exposed to all this beautiful art and landscape and beauty and food, he adores it. But the people that he’s with I’m not sure have the same appreciation or humility about that stuff that he does. So in a way, he’s very like us.”

Scott adds that Ripley’s unsavory exploits are motivated by fear, specifically the FOMO-like certainty that everyone else is having a fabulous time without him. “He’s a dark character and does bad things,” says Scott. “To me, what it’s about is feeling like you are not invited to the party. It’s about feeling like you’re ‘other.’”

It’s hard to blame Ripley for longing for what he can’t have. One early scene in New York sees him gazing admiringly into the window of a refined boutique while on the way home from a dingy dive bar, transfixed — taunted — by an upper-crust lifestyle that is inaccessible to him no matter the cash in his wallet. You can’t merely buy your way into the echelons of high society, or acquire the laissez-faire attitude to wealth that comes with it: Dickie shrugs on his made-to-measure Italian suits with the same careless ease that a dock worker tosses on his overalls. “Essentially, Dickie doesn’t want to inherit the rich kid status,” says Flynn. “In his heart, he’s a bohemian artist-poet, and he’s getting to imagine he is that, living in this reclusive place in Italy.”

This nonchalantly rakish dreamer-gone-adrift casts a particular spell over Atrani’s newest arrival. “To my mind, it’s all about love,” says Scott of Ripley’s attraction to Dickie. “I think he loves Dickie. It’s not really specified as to what the nature of that love necessarily is from Tom’s point of view. Do I think that it’s in some way sexual? Possibly.” Ripley doesn’t know whether he wants to be Dickie, or wants to be with him.

Scott is no stranger to getting into the bones of characters that subvert audience expectations. He recently scored an Olivier nomination for a tour-de-force turn in the West End’s Vanya, an audacious Chekhov adaptation in which Scott played every role. His Ripley is just as multidimensional, teasing out the humanity of a man who is certainly no hero, but is also too complex to quite be a love-to-hate-’em antihero. “I always think the great works of art are or should be about who we are and not who we should be,” says Scott. “I think we contain multitudes within us and all great art reflects that, that we’re both the light and the dark.”'

#Steven Zaillian#Andrew Scott#Dakota Fanning#Marge Sherwood#Dickie Greenleaf#Johnny Flynn#Ripley#Netflix#Vanya#Chekhov#West End#Hot Priest#Fleabag#All of Us Strangers#Robert Elswit#Patricia Highsmith#David Gropman#Atrani#James Moriarty#Sherlock

0 notes

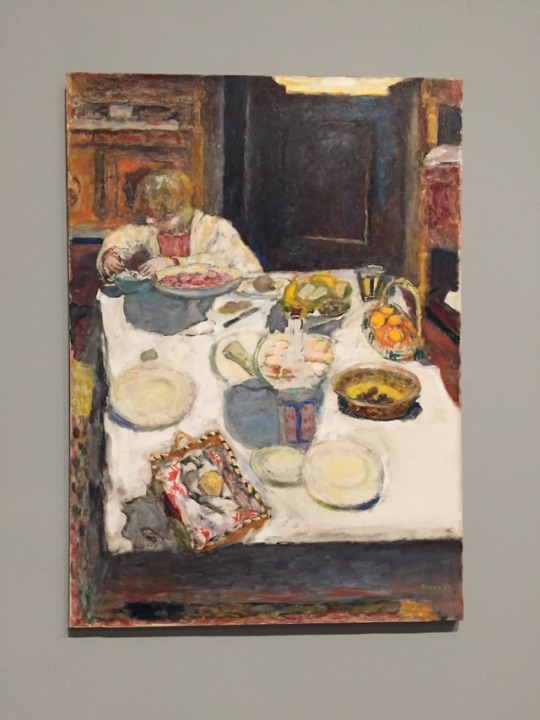

Photo

BONNARD EXHIBITION REVEIW

This exhibition brings together a grand total of 100 carefully selected paintings, photos, sketches, and rare filmed footage of Bonnard himself. With it being the first major exhibition for twenty years of Bonnard’s work in the UK, some are calling it a ‘once-in-a-generation opportunity’. Gale says that at in this collection of works shown at Tate Modern, “we’re trying to look at his work in the context of the 20th century”, through “slow looking tours”. In doing so we discover that his work ventures far beyond just the manipulation of colour.

The themes of the exhibition are made clear through the title ‘Colour of memory’, revealing it to be prominently focusing on colour and memory, but also sub-topically time and domestics. Colour hits you the moment you enter, a range of yellows, hot blues, fleshy pinks, reds, greens all sit together in a dreamlike, chaotic yet structured matter. Loud, bright, yet delicate. The theory behind these colours is that he paints from only memory and preliminary pencil drawings, giving an insight to how he experienced and remembers the scene, but also imposing his own emotions onto the piece through colour. The colourful nature of the paintings give a idyllic beauty and happy reminiscence to the pieces, however there is usurping tone verging on melancholic, in the trying to capture a fleeting moment in time. But he is so effective in transcribing this short lived observation into a permanent statement. Memory was key in the making of his work, as he moved around France a lot in his lifetime , making the mobility of his paintings key despite their finished state. This is successfully portrayed in the various landscapes dotted around the exhibition. The oxymoronic melancholy tone of capturing these fleeting moments, creates an almost eerie and uncomfortable complexion to the paintings, almost deceptive in nature hiding secret truths through their false promises of idealised bliss that we associate with bright colours- this could be reflective of his personal life and marriage.

The work centres unremittingly around his wife Marthe de Méligne and lover Rennée Monarchy, in a homely and almost invasive matter. You almost feel as if you are intruding or overstaying your welcome in a strangers home encountering the personal, unseen nature of a marriage. Marthe’s presence in the work is noticeable from almost the start, parallel to Bannard’s life, they met in their twenties in 1893 and lived together for almost fifty years. The moment you walk through that entrance, feel her presence as if you were in their family home, even when she is absent in a painting her presence and influence is still notable. This makes sense as she was Bonnard’s biggest muse, she would pose and move for his preliminary drawings- some of which are exhibited, the drawings are loose in nature, and capture the essence of the room and the tonal qualities of the room. Although like all marriages there was a hiccup, in his forties with his lover Méligne who similarly modelled for Bonnard. She later killed herself when he returned to his wife after breaking off their proposal. Bonnard’s depiction of Marthe de Méligne in the artwork is vague, she seems to hold no true form, cropped out, often shown from behind, faceless, blurred or distorted, dipping in and out of the bathtub. She never changes, or ages with the timeframe of the paintings, she is stuck in time fittingly like a memory. It makes you question the nature of their relationship and marriage. She was known to be a naturally silent and recluse woman, this silence is reflected in the work, where we see her passively sitting across the checkered clothed table, up at her mundanely pinning up her hair, and below at her catechismal state submerged in the bleak dark water. Encompassed, contained, objectified, and dismissed. She was also known to suffer from many psychological illnesses and to compulsively bathe herself many times a day. This adds a new significance to the domestic intimacy of many of the pieces such as ‘Nu dans le bain’ (1936-8), and ‘Baigneuse, de dos’ where she is displayed faceless infront of a mirror playing with her hair, or lifeless and submerged, with more colour and attention focused on the window behind her than her rag doll frame. While venturing through the many rooms of the exhibition, I noticed that Bonnard has a resurfacing theme of cropping mirrors, never showing the full reflection. It could be seen as a visual metaphor for the self divided, and an unhappy fragmented mind. This is again reenforced by the cropping of the mirror’s reflections which reflect a mutilated and distorted version of her body.

This paradox between idealism and truth, is a dark reoccurring theme within the richly coloured l exhibition. There are a few key pieces in the exhibition that break this serenity that surrounds his artwork, one being the self-portrait ‘a ghost in glasses’. In it we see a reflection of Bonnard himself. He looks aged, tired, drained, a former shell of his once self. We could extend this metaphor of the mirror to Bonnard, portraying instead his fragmented mind and disjointed self, especially as this is painted after the suicide of his once fiancé. His eyes look ghoulish with dark circles. He is a direct reflection of us the viewer looking at him, a stranger to even himself.

The exhibition layout was not overwhelming despite the richness of colour on every wall, and there was space to move and draw, which I always appreciate. I also enjoyed the chronological nature of it, showing his development as an artist, and particularly enjoyed his discovery of white paint in his later paintings. If I had one criticism it would be that I would of liked to have seen the various ‘dining room in the country’ paintings groups, as well as the bath paintings, and particularly the self portraits which felt demeaned and lost in a sea of landscapes.

Its rare for me to leave an exhibition of someone else work, with an overwhelming sense absurdly of who I am myself as an artist, and a better understanding of my own creative practice, the work want to make, and how to strive towards it. I think this is because Pierre Bonnards work, and in particular his colour palette and use of colour in such an inventive way, answered a lot of questions I had been having in my own creative practice concerning colour and colour theory. I left inspired and ready to make work, which I believe is proof of a successful exhibition and of what is truly inspired work of a colour genius.

0 notes

Video

youtube

If you’re a fan of any kind of Fantasy, you undoubtedly know about Lord of the Rings, with its beautiful story, complex characters, and its imaginative and colorful world. The significance of Lord of The Rings for the fantasy and sci-fi genres as a whole cannot be understated. If you were to ask any Fantasy writer, chances are most today would cite Tolkein as an influence in some way. His worldbuilding, personalities, and character archetypes have influenced nearly every corner of literature profoundly.

To be honest, when sitting down to write this episode, it was a DAUNTING task. There’s so much in the lore of Middle Earth, including its expanded universe, where do you even start? In case you didn’t already know, not only was Tolkein influenced by many religious, spiritual, philosophical, and even metaphysical sources, but there are also numerous underlying spiritual messages in his works that hold great wisdom if you know where to look and how to apply it. So let's dive into the Hidden Spirituality of Lord of the Rings!

Intro

To start with, since there’s so much to cover, we should point out that we’re going to be doing it on a movie/book by book basis, starting with this episode on the Fellowship and ending with Return of the King to wrap it up. Hey, we might even include the Silmarillion for all of the nerds out there who want to explore Numenor and Eru Illuvatar!

Now, at its heart, the central theme of LoTR is the quest. On its surface, we see a kind of normal fantasy thing. In essence, the heroes have to overcome the Dark Lord by going on this great journey of self-discovery to conquer the darkness both in the world and within themselves. With Lord of the Rings, it is depicted through the temptation of the One Ring, and the journey to save Middle Earth from its destruction.

But where LoTR begins to get interesting is when you look at the actual pacing of it. The story is completely flipped on its head compared to your average story trope. See, the heroes are not seeking a “treasure,” but are questions to destroy one instead. If we were to look at this same story from Sauron's point of view, the tale is a quest, with Sauron trying to get the treasure back, with the evil Black Riders replacing the traditional "errant knights seeking the holy of holies." The movie begins with a bit of backstory, giving us an awareness of the rings, and the races. We learn about the villain, Sauron, who forged the rings of power and delivered them to the leaders of the tracks who could be controlled, humans, elves, and dwarves. These rings, bestowing power to the bearers, also binds them to the dark lord, which sets the spiritual tone of the story - the idea that absolute power corrupts absolutely, and the deception that evil will use to trap others. In giving these rings to the leaders of the three races, Sauron essentially puts his hold on the world.

But as Sauron's power grows, some fight back, and we see the fall of Sauron at the hands of Isildur, but who is unable to destroy it - another powerful lesson for us still, the temptation that power has over us. What could this ring represent? The story says that into the ring, Sauron poured his cruelty, his malice, and his will to dominate all life. And so the ring ultimately comes to represent these qualities in the form of greed. This can be reflected in our daily lives as any kind of temptation, such as money, fame, sex, all of which can be used to subjugate or manipulate others into doing what you want. In addition to this, the ring bestows the wearer with invisibility, providing a false sense of security, which we can also see in this idea of greed - for as you generate more money or fame or what have you, it gives you this sense of security, but real security - as the story also teaches us, comes from the connections that we have with our friends and family.

One of the things that Sauron creates is feelings of absolute despair through facilitating the creation of evil forces, such as manipulating Saruman, to do his bidding in creating an army of orcs and uru-kai. Gandalf, on the other hand, has the reverse power, supporting others to resist the temptation of despair, and rekindling hope and courage wherever he goes. That Tolkien was conceiving these works during England’s darkest days during World War II, gives a unique context to this power to resist fear and despair.

It would also seem that Tolkein uses this narrative, especially the easily swayed humans, to describe the over-inflated ego and the dangers of what can happen when your desire and ambition are left unchecked. From this viewpoint, it appears that the Fellowship is on a quest to destroy the ego and ultimately free the world from the dark influence of desire and temptation. Tolkien had lived through two world wars, including the "routine bombardment" of civilians, the use of famine for political gain, concentration camps, and genocide, and the development and use of chemical and nuclear weapons, and so much of this story, although based in a different world than ours, is very much rooted emotionally and contextually in severe and real events in history.

The story raises the question of whether, if the ability of humans to produce that kind of evil could somehow be destroyed, even at the cost of sacrificing something, would it be worth doing.

Now, if any of this talk of desire, temptation and evil sound familiar, that’s because Tolkein was devoutly Catholic, a trait which he admitted to having been a profound influence on his writings. While it is interesting that he never included a direct form of religion in his main body of work, the themes, moral philosophy, and cosmology of The Lord of the Rings reflect his Catholic worldview. Christian items are ever-present in much of his work, more so in the later books -especially return of the king, which we will cover when we get there, many of the ideas focus around death, resurrection, forgiveness, grace, repentance and of course, free will.

Even Tolkien himself said, "Of course God is in The Lord of the Rings. The period was pre-Christian, but it was a monotheistic world," and when questioned who was the One God of Middle-earth, Tolkien replied, "The ONE, of course! The book is about the world that God created – the actual world of this planet." Delving a bit deeper into the language of Middle Earth, even the name itself comes from the Norse Midgard - which was the name for our earth.

The influence of Norse Mythology for Tolkein was HUGE. There are some excellent videos out here on YT that talk about the Mythology of LoTR, so if you want to go deeper, we recommend looking this up. Everything from the characters to the environments is rich in symbolic meaning.

Let’s take Gandalf, for instance. Speaking purely from Tolkein’s point of view, Gandalf was mostly based off of the Norse God Odin Who is a bit different from the Marvel version you’re probably familiar with. Odin, in Norse Mythology, is described as "The Wanderer," an old man with one eye, a long white beard, a wide-brimmed hat, and a staff. Tolkien, in a 1946 letter, nearly a decade after the character was invented, wrote that he thought of Gandalf as an "Odinic wanderer." Much like Odin, Gandalf promotes justice, knowledge, truth, and insight. His battle with the Balrog in the Mines of Moria was meant to mirror that of the fight with Surtr spiritually, the Fire Giant in Norse Mythology, with the ensuing collapse of the Bridge of Khazad Dum mirroring the prophesied destruction of the Bifrost during Ragnarok.

Interestingly though, it should be said that Ragnarok was not seen as the end of the world as it is often thought, but rather the beginning of a new cycle, and this is essentially what happens in the Fellowship, with the fall of the Balrog and the collapse of the bridge, it gives way for the journey to unfold. Gandalf had to fall to be reborn as a higher, more ascended, and powerful being than he was before.

As we looked at, there are several key races in the story, which seem to spiral around the elements. This is not spelled out directly by Tolkien. Still, it would appear as though the humans reflect the element of Fire, showing their passionate ways, leadership qualities, and also a bit of their destructive power, and even in Return of the King we see that it is time for humans to take the throne as the new world leaders, further reflecting the fire being the closest to the Godhead in the alchemical systems. The Dwarves are Earth for probably obvious reasons, the Elves are Air with their both living in the trees, their precision, their mental acuity and awareness of the world, and Hobbits as Water - being natural, flowing, and most importantly, nurturing qualities, a trait that is often described as the highest form of the divine feminine, manifested through the alchemical element of water, or the emotional body. If we were to count wizards and orcs, we would see angels and demons join the fray with the aspects of Aether and Voidness, the latter of which stands for lack of substance.

Now speaking of Hobbits - the Shire itself represents an idyllic haven, where the hobbits live in harmony with nature and each other, creating an environment of peace, love, and pleasure. Even though not all hobbits get along and are mainly stuck in their ways, their ways are that of connection with the spirit of the earth. In many ways, living in the shire might be what we would think would be the end goal for many characters, a peaceful haven where evil doesn’t exist, reminiscent of the English Countryside.

We also see some new numerology here. As the story opens, we see Bilbo celebrating his eleventy-first birthday, which in the book just so happens to be on the same day as Frodo celebrating his coming of age birthday, as he turns 33. In Sacred Numerology, 111 signifies manifestation and prosperity. This number's central symbolism is manifesting thoughts into reality and is also said to symbolize awareness, uniqueness, motivation, and spiritual awakening. This makes sense as shortly after Bilbo’s celebrations; he slips away to go on a new journey in his life.

Frodo’s age is also hugely significant, as 33 in Christian numerology is the age Jesus was when he was crucified in the year 33AD. We might even go as far as to say that no number holds more esoteric significance than “33.” The number three is significant in all major religions, with there being a Trinity for Christians and even a trinity of Goddesses or Deities in many ancient cultures. The number 33 was also crucial to secret societies and is often concealed within significant literary works. There are even 33 degrees in modern Freemasonry. At the Vatican, there are 32 archways on each side of the courtyard with a giant obelisk in the middle, and the Pope’s cassock has 32 buttons with his head representing the 33rd.

Furthermore, the first Temple of Solomon stood for 33 years before being pillaged. Alexander the Great also died at 33, and Pope John Paul I was murdered after being in power for only 33 days. And if that wasn’t interesting enough, in the movie we see all of this happen on the 22nd of September! So all together, we have 111, 22, and a hidden 33.

When we first meet Bilbo and Gandalf, Bilbo is unwilling to give up a ring, a sign of being unable to let go of his worldly attachments and temptations. Eventually, after much persuasion from the Wizard, he gives it up and is relieved of a considerable burden, symbolic of him reducing his ego of its duty. When Gandalf returns later on to visit Frodo, he casts the ring into the fireplace, revealing the engraved Elvish Script. Isn’t it remarkable how the Black Speech of Mordor can be so beautiful and yet so evil at the same time? It's a scenario reminiscent of Lucifer, who was said to be the most beautiful of God’s angels, don’t you think?

Along with the strength of will, the value of wisdom is also integral to the underlying spirituality of The Lord of the Rings. Although I’m sure Tolkien never intended it this way, we find the elves to be the embodiment of and reminiscent of Taoist wisdom. Like the Taoist sage, the elves, for the most part, are free of the discontent that so affects humans. They love the natural world and govern their lives in harmony with it. They dedicate their creative powers to fashioning things of beauty that enhance the natural world without damaging it. Their dwellings bring to mind the houses in the tremendous Taoist landscapes — habitations in harmony with their environment. All of this, like the ideal government of the Tao Te Ching, is so at odds with our actual world that “fantasy” is an apt term for it. But it does bring to mind the kind of world, beings who were born with inner contentment might create. And in doing so reminds us of the degree that the world we have created is carried of our discontentment.

Leading up to their meeting in Rivendell, Frodo is stabbed by a Nazgul blade that begins to slowly infect him, which Aragorn says can only be healed by Elven Magic. If we look at it from a higher perspective, the Nazgul are creatures of Necromancy, fueled by dark magic and hatred. By being stabbed, perhaps that hatred and despair begin to enter Frodo slowly, but given that Elven magic is born solely out of love and compassion, it is the only thing that can heal a wound of fear and hatred. Much like our current situation, love is the sole real remedy for anxiety. It is no coincidence that Frodo meets Bilbo here again, as the environment itself is one of healing and repentance.

Now the first book and movie are called the Fellowship of the ring, and on a base level, it arguably represents the bonds of brotherhood and family and this idea that no one race is better than another. In this, we find that even once enemies can become friends, such as Legolas and Gimli. Although the fellowship was not meant to last, the establishing of this shared intention between all of them is ultimately what allows the entire story to transpire once they reach Rivendell.

During the council of Elrond, we see that the presence of the ring and the conversation stirs everyone to arms with each other. And honestly, if each of them tried to destroy the ring on their own, they would all fail and ultimately become corrupted by it. The only one who can do it is Frodo because he represents the purity and innocence of the natural soul, and even then, the ring still gets to him slowly but surely by the end. Nevertheless, only by having a united Fellowship made up of each of the world’s races can they hope to succeed. There is undeniably a lesson is cooperation here, only by working together and lifting each other when we can accomplish something seemingly impossible, and this is an excellent lesson for us to recognize in the world today. There is more power in unity than in separation. From a spiritual perspective, perhaps the experience here is that by creating and maintaining an environment of mutual trust and harmony and working together and creating a space for that kind of movement and growth to occur can we too “do the impossible” and curb our desires and egos, allowing us to exist in harmony with our world, collectively.

Also, it is impressive that the Fellowship numbers nine people (2 humans, an elf, a dwarf, four hobbits, and a wizard), along with their being 9 Nazgul. There's probably some strong numerology in there somewhere, as 9 is a very significant number numerologically. But for now, let's just say the two “groups” create a sense of balance, one for one.

Throughout the story, we also see the theme of personal sacrifice, over and over. I wonder if this was inspired by Tolkiens own spirituality, reflecting Jesus - who gave his own life because it was what must be done. Frodo went on the journey to take the Ring to Rivendell, and then to Mount Doom, sacrificing his old life, his old way of being, and things would never be the same again for him.

Further, Gandalf decided to allow Frodo the choice to take either the Mines or Mountains after leaving Rivendell, a decision which ultimately led to Gandalf’s death and Christ-like resurrection. While the majority of these scenes take place in the next film, it is significant that Gandalf dies his purpose, protecting and guiding the others. In doing so, he is allowed to return by the One as a much more leveled up Gandalf the White, taking the place of Saruman as the benevolent white wizard. The color symbolism here cannot go unmentioned, as his transition from Grey to White is arguably symbolic of him “shedding the veil of the night” (to quote our good friend Thoth in the Emerald Tablets) and becoming a real ascended being. This transition into ascension is also present with Galadriel in Lothlorien towards the very end of the film. For people who have only seen the movie version of The Lord of the Rings, we see a little context for Galadriel’s actions and words after she resists taking the ring. Even the book version does not provide the full context. But in the appendices at the end of The Return of the King and in The Silmarillion, we learn that Galadriel’s character flaw is the desire for power. This flaw she shares with her ancestors, who were exiled from the Far West due mainly to their pride and aggression. Through sharing in this exile, Galadriel was always torn by her love of the world and its beauty and her desire for power. Through the ages of Middle Earth, she steadfastly pitted her will against the will of Sauron, and in doing so, served in the protection of beauty and harmony against chaos and destruction. With this background, we can better understand the scene where Galadriel is finally offered the ring of power by Frodo. A part of her had long desired such an opportunity, yet she can resist this temptation, and in doing so, she finally can relinquish her desire for power. Having done so, she knows that the condition of her exile has been lifted and that she can return to the Far West, symbolic of her ascension and moving into a new life for herself.

Even the gifts of Lothlorien themselves have spiritual meaning. Frodo’s “Light of Earendil” that illuminates the darkness seems to signify light as purifying energy that provides hope, warmth, and shows the way. Interestingly there is a slight difference in the gifts that Sam gets from Galadriel. In the movie, he receives an Elven rope that can be easily anchored up by a simple tug, but in the book he receives soil from Galadriel’s garden and a seed, which he uses to replant the trees in the Shire after it is destroyed, signifying a spiritual rebirth and ultimately resurrection of the Earth. It makes sense that this item was changed for the movie because the destruction of the shire was cut from the film adaption.

The movie ends with Frodo disbanding the fellowship under the premise that the ring holds too much temptation to be able to keep the group together. Once again, he makes a substantial sacrifice for what he sees as the highest good. But like always, love is the answer. Sam, knowing Frodo as a friend, immediately guesses where he is going and follows him into what is quite literally the mouth of hell, signifying the bonds of brotherhood and family transcend even the darkest of darkness.

On that note, let’s bring this to a close. There is so much more that we could have spoken about here, and believe me, it was tough to condense this into just one video, but hey, at least we have two more to go! We will expand on each of these themes and delve more into them as we make our journey to Mt Doom by working through the story.

0 notes