#the afrikaner Nationalist party

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ask an older generation of white South Africans when they first felt the bite of anti-apartheid sanctions, and some point to the moment in 1968 when their prime minister, BJ Vorster, banned a tour by the England cricket team because it included a mixed-race player, Basil D’Oliveira. After that, South Africa was excluded from international cricket until Nelson Mandela walked free from prison 22 years later. The D’Oliveira affair, as it became known, proved a watershed in drumming up popular support for the sporting boycott that eventually saw the country excluded from most international competition including rugby, the great passion of the white Afrikaners who were the base of the ruling Nationalist party and who bitterly resented being cast out. For others, the moment of reckoning came years later, in 1985 when foreign banks called in South Africa’s loans. It was a clear sign that the country’s economy was going to pay an ever higher price for apartheid. Neither of those events was decisive in bringing down South Africa’s regime. Far more credit lies with the black schoolchildren who took to the streets of Soweto in 1976 and kicked off years of unrest and civil disobedience that made the country increasingly ungovernable until changing global politics, and the collapse of communism, played its part. But the rise of the popular anti-apartheid boycott over nearly 30 years made its mark on South Africans who were increasingly confronted by a repudiation of their system. Ordinary Europeans pressured supermarkets to stop selling South African products. British students forced Barclays Bank to pull out of the apartheid state. The refusal of a Dublin shop worker to ring up a Cape grapefruit led to a strike and then a total ban on South African imports by the Irish government. By the mid-1980s, one in four Britons said they were boycotting South African goods – a testament to the reach of the anti-apartheid campaign. . . . The musicians union blocked South African artists from playing on the BBC, and the cultural boycott saw most performers refusing to play in the apartheid state, although some, including Elton John and Queen, infamously put on concerts at Sun City in the Bophuthatswana homeland. The US didn’t have the same sporting or cultural ties, and imported far fewer South African products, but the mobilisation against apartheid in universities, churches and through local coalitions in the 1980s was instrumental in forcing the hand of American politicians and big business in favour of financial sanctions and divestment. By the time President FW de Klerk was ready to release Mandela and negotiate an end to apartheid, a big selling point for part of the white population was an end to boycotts and isolation. Twenty-seven years after the end of white rule, some see the boycott campaign against South Africa as a guide to mobilising popular support against what is increasingly condemned as Israel’s own brand of apartheid.

. . . continues at the guardian (21 May, 2021)

#israel#palestine#gaza#south africa#i think all of us need to seriously study the history and actions of the anti-apartheid movement#and apply these lessons to the israeli occupation

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

sarie ethnicity musings (with historical context!!)

It’s hard to overstate just how much Sarie’s Jewishness impacts her as a character, specifically how she views herself in relation to other people. Afrikaans-speaking Jews (Boerejode) lived mainly in rural areas where knowledge of Afrikaans would be needed in daily life (mainly the rural Cape and the Transvaal). However, the biggest waves of Jews immigration came from Lithuania in the 1880s and 1890s, followed by an influx of German Jews in the 1930s. Most of these immigrants (with the exception of people like Sarie’s mom who married into Afrikaans-speaking families) settled in cities like Cape Town, Johannesburg, and Durban, where knowledge of Afrikaans wasn’t needed. So right off the bat, Sarie is alienated from the vast majority of her community by virtue of being Afrikaans-speaking.

But that doesn’t mean she belongs among the Afrikaans-speakers, either! White Afrikaans-speaking (Afrikaner) identity is fundamentally tied to adherence to a deeply-rooted Calvinist tradition (non-white Afrikaans-speakers are generally split between Calvinism and Islam). For a nationalist hardliner, it’s impossible for a Jew (or even a Catholic or an irreligious person) to be considered an Afrikaner, regardless of how White or Afrikaans-speaking they are. And in the 1930s and 1940s, these kinds of hardliners were everywhere.

The intensification of Afrikaner nationalism in this period would culminate in the accession to power of the National Party in 1948, which would go on to enjoy both the near-unanimous support of Afrikaners as well as considerable support (albeit less fervent and at times more tacit) from white English-speakers for the next forty-odd years. Expanding on the structures left behind by English colonial rule, the successive National Party governments would institutionalize the draconian policies of mass disenfranchisement, arbitrary displacement, censorship, economic disempowerment, imprisonment, and segregation — all enforced through brutal violence against non-white populations — that we know as apartheid.

Sarie is born at the tail end of 1921, meaning she comes of age in the mid-to-late 1930s. This is where it’s necessary to elaborate on the role that the Depression played in the upswing of Afrikaner nationalism. Lord Kitchener’s scorched-earth policy in the second half of the 2nd Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) destroyed thousands of Afrikaner farmsteads across the northern Cape, Orange Free State, and Transvaal. Afrikaners had always been an agrarian people; in 1947, less than thirty percent of all Afrikaners worked outside of agriculture. The loss of land forced a majority of mid- and small-scale Afrikaner farmers to either become sharecroppers for English and wealthier Afrikaner landlords, or go into mine or factory work in the cities and towns along the Rand. And as in all societies, these groups were hit hard by the Depression, leaving many Afrikaner workers, poor to begin with, destitute (farmers, especially wool farming families like Sarie's, would also be significantly affected). Suddenly, Afrikaners found themselves living in the same slums, standing in the same job lines, and eating the same food as their Black counterparts — and this is what sparked alarm in the middle-class and wealthy Afrikaner establishment.

Fearing that Afrikaner destitution would erode the myth of white supremacy which legitimized minority rule (or, to take a more Marxist perspective, that the poor Afrikaners would gain class consciousness), Afrikaner nationalists and their English supporters spent untold amounts of time and effort trying to rectify this supposed reversal of the “natural” racial hierarchy. This would culminate in the Carnegie Commission of Investigation on the Poor White Problem in South Africa, a 1932 report by the Carnegie Corporation which recommended racial segregation as a solution to the “problem” Throughout the 1930s, Afrikaner nationalists would appeal to the mythical Voortrekker (pioneer) past to foster increased national affiliation. This would culminate in the 1938 Voortrekker Centenary, which saw Afrikaners reenact the trek from the Cape to the interior taken by their ancestors a century earlier.

Sarie would have felt this increase in nationalism acutely, not just as someone whose religious affiliation excluded her from the mainstream Afrikaner milieu, but as a woman. The ideal Afrikaans woman, the “boeremeisie” (farm girl) or “volksmoeder” (mother of the people), was, in the words of author Lize van Robbreck’s high school principal, “proper, humble, and chaste.” Van Robbreck was the daughter of Catholic Flemish parents, and while she had spoken Afrikaans her whole life and been raised on a steady diet of folk dance and traditional songs, in her Afrikaans high school she realized that her Catholic heritage fundamentally differentiated her from her peers. “I could never be one of them, no matter how hard I tried.” Sarie, as both a Jew and as a woman who is neither proper, humble, nor chaste, already finds herself distinctly isolated from the other girls at her school.

And yet, at the same time, I think that Sarie does, to an extent, resent this exclusion. While she frowns on the racial discrimination and antisemitism inherent in Afrikaner nationalism of this era, and as much as she takes pride in going against the grain (manifesting in an admittedly not-like-other-girls attitude towards her fellow Waasies), a part of her is still desperately searching after the validation from her peers, the validation of inclusion, that she was never going to be able to receive. This, I think, is what fuels her continuous affirmation of her South African — and Afrikaans/Boer — identity amongst her fellow soldiers in the SAS. In the SAS there’s nobody who can call her out, who can deny her Boer identity — even if it’s just by virtue of the fact that they don’t know enough to say otherwise. However, I don’t think that Sarie herself would realize that this is what’s pushing her — to her, she’s just explaining her identity with the same aggression she has always had to use to justify herself. I think that there's a reason that Sarie only ever refers to herself as a Boer or a Boerejood, and never, ever, as an Afrikaner.

I’m probably going to follow this up with a whole other essay just about her gender but I spent all of today flying home and there’s hockey on TV and I’m tired so this is all you’re getting for now. Thanks for reading this absolute fucking thesis of an OC post <3

#ch: sarie#notes from the front#!!!!!!! spinning her in my head like soup in the microwave#sas rogue heroes

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

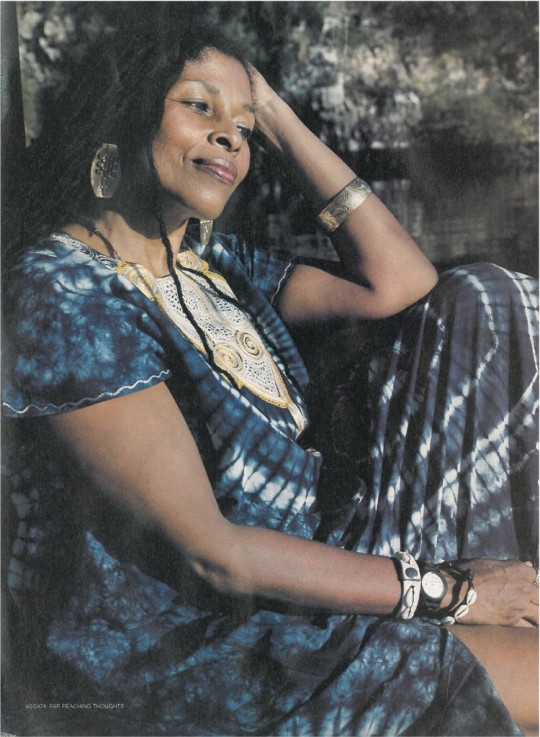

Assata: An Autobiograhy - Assata Shakur

Hello friends!

I’m incredibly excited for this week’s recommendation as we start Black August, a month dedicated to highlighting the history of revolutionary Black political prisoners and their comrades in and outside the US. I’ll be highlighting a crucial radical Black woman’s experience today: “Assata: An Autobiography” by Assata Olugbala Shakur.

While Assata needs no introduction, here’s a quick biography before delving into the text. Assata Shakur, born JoAnne Deborah Byron on July 16, 1947, is a New Afrikan revolutionary and former member of the Black Liberation Army and Black Panther Party. She grew up between New York and North Carolina, experiencing the worst of Jim Crow, and was radicalized by the Vietnam War in college. After joining the BLA for a while, she was present in a shootout on a New Jersey Turnpike that left a state trooper dead in 1973. She was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison, but she escaped in 1979 and fled to Cuba, where she was granted political asylum and lives in to this day.

There are too many aspects of Assata's storied history to highlight here, all of which deserve serious reflection. I'll start by noting her incredible bravery and fortitude throughout her harrowing encounters with white supremacy, patriarchal violence, and settler capitalism in and out of prison. As her name shows, she is one who thankfully struggles for the people.

Her position as a socialist revolutionary is important to highlight. She was a part of a militant black freedom struggle rooted in communist thought which sought to upend global imperialism and colonialism to free all peoples, especially black women as some of the most exploited Third World Women (seeing New Afrika as a colony). She also criticized white chauvinist elements of the Left which sadly still exist.

I also want to mention her solidarity with Lolita Lebrón, an incredibly important Puerto Rican nationalist, in prison when no one else would. She knew that decolonization for Puerto Rico was a part of a global struggle for liberation.

I highly recommend everyone read this book to gain first-hand insight into a Black revolutionary's struggle for freedom!

#book blog#book review#bookblr#assata shakur#black liberation#communism#socialism#women's liberation#black august

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The best-known of [interwar South Africa’s] overtly anti-semitic Nazi movements was The South African National Party (originally called The South African Gentile (Christian) National Socialist Movement), and its uniformed section, the Greyshirts, detailed to ‘protect’ its founder and leader, Louis Weichardt. The founding of the Greyshirts, he wrote:

was greeted with a howl of rage from South African Jewry and likewise from those renegade Europeans (‘Gentile Hoggenheimers’, as they are commonly called) who include the greater number of our professional politicians and who show more diligence and zeal than even the Jews themselves in exploiting and oppressing the unhappy South African people. ...

Weichardt believed that his party should work towards ending the antipathy between Afrikaans and English-speaking South Africans, and that the way to do this was to demonstrate the difference between ‘British imperialism’ – a positive force – and ‘capitalist-Jewish-finance imperialism’, which, if the Afrikaner but knew it, was the true cause of his suffering. Moreover, the British themselves had to realize that Britain’s world role had to be reformed “if White Christian European civilization is to be preserved as the directing force in the world.”

Much of the propaganda which the Greyshirts and other imitation Nazi movements in South Africa published was translated, or reproduced in the case of cartoons, directly from Nazi journals, and the Nazi periodical Blitz even carried a South African newsletter. It must not be assumed, however, that this sort of political pornography was easily accepted by a majority of Afrikaner Nationalists at first. In 1934, Die Burger attacked the authoritarian structure of the Greyshirt movement, and in 1936 [National Party leader] Malan was still able to attack anti-Semitism, although his statement was based on a broader racism. In South Africa he argued, “we cannot discriminate against the Jewish race or any other race. All who are white in this country deserve to stand on an equal footing politically and otherwise.”

— Jeff J. Guy, “Fascism, Nazism, Nationalism and the Foundation of Apartheid Ideology” in Fascism Outside Europe, ed. Stein U. Larsen

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Given the presence of an Afrikaner nationalist party in South Africa's ruling coalition, I am skeptical of those genocide claims.

0 notes

Text

This second source is another pamphlet, dating to December of 1980, with this one advertising to Nottingham University students to come join the society’s fight against South Africa’s system of racial segregation.

The implementation of apartheid started in South Africa with the election of the Afrikaner Nationalist Party in 1948 (Clark and Worger 2022, South Africa: The rise and fall of apartheid, p. 37). Why it was put into practice was down to a multitude of factors: economically through ensuring a low-paid African workforce was available for white business owners to make large profits off of, culturally through the maintenance of Afrikaner society and culture, and historically through the development of previous segregation legislation already in place by 1948 (Clark and Worger 2022, South Africa: The rise and fall of apartheid, p. 37).

The pamphlet mentions the “Obligatory classification of every human being into 4 Racial groups” under apartheid, which was first introduced under the Population Registration Act of 1950 (Clark and Worger 2022, South Africa: The rise and fall of apartheid, p. 49). In addition to the racial categorisation of South Africa’s population, the Act also instituted the issuing of identity cards which listed the assigned race of an individual (Clark and Worger 2022, South Africa: The rise and fall of apartheid, p. 49). This was used to judge any person’s access to legal rights within the country (Clark and Worger 2022, South Africa: The rise and fall of apartheid, p. 49). Other aspects of life under apartheid cited by the pamphlet also had its roots in 1950s legislation, such as the Immorality Act, which prohibited sexual relations between whites and non-whites, and the Group Areas Act, that designated one group to a particular area for occupation and forcibly removed existing occupants from said area (Clark and Worger 2022, South Africa: The rise and fall of apartheid, p. 52).

#nottinghamsrebelliousstudents

0 notes

Text

#SouthAfrica #ElonMusk #DonaldTrump #Politique Le président sud-africain Cyril Ramaphosa a récemment rejeté avec fermeté les allégations selon lesquelles la minorité blanche du pays, en particulier les Afrikaners, serait victime de persécutions systématiques. Ces accusations, portées par des figures telles que Donald Trump et Elon Musk, ont suscité un débat international sur les tensions raciales en Afrique du Sud. Ramaphosa a qualifié ces affirmations de "narratif complètement faux" et a exhorté ses concitoyens à ne pas se laisser diviser par des discours provenant de l’étranger. Elon Musk, né en Afrique du Sud, a ravivé la controverse en publiant sur les réseaux sociaux que certains leaders politiques sud-africains promouvaient activement un "génocide blanc". Cette déclaration faisait référence à un rassemblement du parti d'opposition Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), où un chant controversé datant de l'ère de l'apartheid a été entonné. Musk et Trump ont également critiqué les lois foncières sud-africaines, les qualifiant de discriminatoires et accusant le gouvernement de ne pas protéger suffisamment les fermiers blancs. Cependant, le gouvernement sud-africain a réfuté ces accusations, soulignant qu’aucune preuve ne démontre une persécution ciblée des fermiers blancs. Les statistiques policières montrent que les crimes violents touchent toutes les communautés sans distinction raciale. Les experts attribuent les attaques contre les fermiers à leur isolement géographique et à leur richesse relative, plutôt qu’à des motifs raciaux. Ils dénoncent également la diffusion d’un narratif exagéré par certains groupes nationalistes blancs. Les tensions ont été exacerbées par une décision récente de Donald Trump visant à suspendre l’aide américaine à l’Afrique du Sud et à offrir un statut de réfugié aux Afrikaners. Cette mesure a été critiquée comme étant basée sur des informations infondées et risquant d’aggraver la situation économique et sociale des populations vulnérables dans le pays. Ramaphosa a réaffirmé son engagement envers la cohésion sociale et la lutte contre la désinformation. Il a appelé à rejeter les discours qui divisent et à se concentrer sur le renforcement de la démocratie sud-africaine. Alors que ces débats continuent d’alimenter les tensions internationales, le président insiste sur l’importance de préserver l’unité nationale face aux défis internes et externes. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

On Oct. 22, Devlet Bahceli, the leader of the far right Turkey’s Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and a key ally of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, stunned the country by suggesting that Abdullah Ocalan—the leader of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which Ocalan founded in 1978 and that has waged an insurgency against the Turkish state since 1984 and is listed as a terrorist organization by Turkey as well as the United States and the European Union—should be granted parole if he renounces violence and disbands the organization.

Ocalan has been serving a life sentence since 1999 on the prison island of Imrali, located to the south of Istanbul. Bahceli proposed that the leader of the PKK be given the opportunity to make this announcement in an address in the Turkish parliament directed to the pro-Kurdish, left-wing Peoples’ Equality and Democracy (DEM) Party.

The Kurdish political movement has a broad base among Turkey’s Kurds. In the 2023 parliamentary election, the Peoples’ Democracy Party (HDP)—the DEM Party’s predecessor— received just over 46 percent of the votes in the predominantly Kurdish provinces. However, like its earlier incarnations, the pro-Kurdish party largely remains in the shadow of the PKK. Presumably, Bahceli believes that the symbolic effect of Ocalan’s statement would be all the more profound if delivered to the political wing of the Kurdish movement. In that case, the legal obstacles to granting him parole would disappear, Bahceli said.

When the Turkish parliament reconvened on Oct. 1, Bahceli had unexpectedly shook hands with the lawmakers of the pro-Kurdish party. The far-right leader stressed the importance of national unity and brotherhood and said, “We are entering a new era, and when we call for peace in the world, we must also secure peace in our own country.”

By making these statements, Bahceli has assumed a role that is akin to that of South Africa’s F.W. de Klerk in the early 1990s. De Klerk was the president of South Africa from 1989 to 1994 and served as the last leader of the white minority National Party, which ruled the country brutally from 1948 to 1994 and institutionalized the system of apartheid that made nonwhite South Africans second-class citizens. The National Party also fought a series of wars against anti-colonial independence movements and attacked Black-led neighboring states that hosted exiled anti-apartheid leaders.

Yet de Klerk broke the taboos of Afrikaner nationalism by freeing anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela in 1990 and negotiating the transition to democracy.

The MHP also has a history marked by violence. Between 1975 and 1980, MHP activists—who were known alternatively as the Gray Wolves or Idealists —took to assassinating left-wing students, state officials, and intellectuals. In response, some left-wing groups also took up arms. The party’s leader, the former army colonel Alparslan Turkes was arrested when the military took power in a coup 1980, but he was later acquitted.

Turkes then softened his rhetoric, committing himself to nonviolence. The MHP’s transformation continued when Bahceli, an economics professor who was untainted by the party’s violent past, succeeded Turkes upon his death 1997. In 1999, Bahceli joined the government of the leftist Bulent Ecevit, the MHP’s arch-enemy in the 1970s, as deputy prime minister. Bahceli has since then played a key role at critical junctures in Turkey’s politics.

In 2000, Bahceli accepted a moratorium on the execution of Ocalan—who had been sentenced to death after he was captured in Nairobi, Kenya in February 1999 and extradited to Turkey. (The death sentence was commuted to a life imprisonment in 2002.)

In 2002, Bahceli precipitated the fall of Ecevit’s coalition government by calling for the snap election that brought the Islamic conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) to power; it has since ruled the country for more than 20 years. However, the MHP remained part of the opposition until 2016.

When the AKP government engaged in peace negotiations with Ocalan between 2013 and 2015, Bahceli denounced the peace process, saying that “there is no difference left between the AKP and the PKK.”

At that point, Turkey sought an agreement with the PKK because Ankara feared the effects of the empowerment of the Kurds in northern Syria, where the PKK-affiliated People’s Protection Units (known as the YPG) had established a de facto autonomous region in 2012. But in 2015, the fighting resumed when the PKK sought to subvert government control in Turkey’s predominantly Kurdish southeastern region.

In 2016, when Erdogan’s erstwhile allies—the followers of the Islamic cleric Fethullah Gulen—mounted a coup against Erdogan, Bahceli shifted course. The coup failed, but the Turkish state had been deeply fractured, and it was imperative to shore up its power and authority. With this in mind, Bahceli called on Erdogan to make a transition to a presidential system, and in 2018, the AKP and the MHP entered into a formal alliance that was crucial for the AKP.

Indeed, Erdogan owed his reelection in 2018 and 2023 to the support of Bahceli, and the AKP government retains parliamentary majority today thanks to the MHP. In the 2023 parliamentary election, the AKP won 268 seats of 600 seats, and the MHP won 50.

The partnership runs deep: Erdogan’s government has espoused the nationalism of the far right, and MHP officials now populate the state bureaucracy and the judiciary, where they have replaced the Gulenists after the attempted coup.

But the AKP’s dependency on the MHP and hard-line policies has cost the ruling party—which has been in steady electoral decline since 2018—the support of the Kurds, once an important part of the party’s base.

Today, both domestic political considerations and regional developments have compelled Erdogan’s government to reconsider its Kurdish policy. In a statement published on Oct. 22, the DEM Party assessed that “the encirclement of Iran in a ring of war has raised the possibility that the Kurdish people will play a decisive role.”

The pro-Kurdish party seems to believe—correctly—that the specter of ethnic violence is haunting the AKP-MHP regime, and that this is a revolutionary moment. The statement issued by the DEM assembly on Oct. 22 expressed hard-left militancy: “Our party believes that the real solution is to be expected not from the government, but that it will be made possible by organizing the joint struggle of Turkey’s labor and oppressed groups and peoples,” it read.

Bahceli believes that he had to take this initiative to prevent the loss of territory for Turkey, MHP deputy chairman Yasar Yildirim explained at a meeting on Nov. 17.

The republication on Oct. 14 by the pro-PKK daily Yeni Ozgur Politika of an old article by Ocalan, in which the PKK leader enjoins the Kurds to enter into an alliance with the United States and Israel against Turkey, Iran, and Syria, is sure to have confirmed and reinforced Turkish concerns. Indeed, such an alliance has already formed in northern Syria, where the PKK’s affiliates are armed and protected by the United States, to the consternation of Ankara.

And on Nov. 10, new Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Saar said that the Kurdish people “are our natural ally.” Describing the Kurds as victims of Iranian and Turkish oppression, Saar argued that Israel “must reach out and strengthen our ties with them.”

The war and chaos in the Middle East have made the Turkish elite attentive to the need, in the words of Erdogan, to “fortify the home front” by defusing domestic ethnic tensions. But Erdogan could not risk antagonizing Bahceli and nationalist opinion. Neither could he realistically hope to succeed with a new opening to the Kurdish political movement without the sanction of the party that is the principal proponent of Turkish nationalism.

But like South Africa’s de Klerk in the early 1990s, Bahceli also has to contend with radical nationalists who cry treason. In response, Bahceli has exhorted the nationalist opposition to be realistic and finally come to grips with the Kurdish reality. He pointed out during a speech to the parliamentary group of the MHP in early November that keeping Ocalan incarcerated has not prevented the Kurdish voters from reelecting representatives to parliament who share his views.

For decades, the Turkish state refused to acknowledge the existence of the Kurds—claiming that they were ethnically Turkish, banning the Kurdish language, and forbidding other expressions of the Kurdish identity—and sought to assimilate them. The tolerance of ethnic and religious diversity that defined the Ottoman Empire has been anathema to contemporary Turkish nationalists.

But just as de Klerk renounced apartheid, Bahceli now appears to be repudiating Turkish ethnic supremacy. He has started praising Ottoman diversity: “The Ottoman Empire secured peace and security by keeping local cultures and ethnic groups together, and we can accomplish the same by following in their footsteps.”

Bahceli’s claim that the “Turkish nation has never sought assimilation (of others) during its history” is demonstrably false, but is nonetheless remarkable insofar as it rejects the nation-building strategy of Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey, who sought to assimilate Kurds and other Muslim, non-Turkish ethnic groups.

The Ataturk cult is an impediment to liberalization. When Turkish Armenian economist Daron Acemoglu, a Nobel laureate in economics this year, recently pointed out that Ataturk concentrated power into his hands when he instead could have built on the pluralistic legacy of the Ottoman Empire, Kemalist nationalists blasted him. A celebrity actor demanded that he “bow respectfully to the savior of the nation.”

Bahceli seems to hope that Ocalan can be Turkey’s interlocutor in the same way that Nelson Mandela was to de Klerk. Responding to Bahceli’s overture, Ocalan—in a message relayed by his nephew, who is also a DEM Party member of the Turkish parliament—said that “if the conditions arise, I possess the theoretical and practical strength to pull this process away from fighting and violence toward a legal and political platform.”

Yet it was immediately clear that such conditions have yet to arise.

On Oct. 23, the day after Bahceli raised the specter of Ocalan’s release, the PKK carried out a terrorist attack, for which the organization claimed responsibility, against a military-industrial complex outside Ankara, killing five civilians.

Bahceli may soon discover that Ocalan does not command authority in the same way Mandela did. However, Mandela was offered a similar conditional release deal in 1985, which he rejected. Ocalan may even be trying to mimic Mandela’s refusal. It wasn’t until after de Klerk freed him in 1990 that the African National Congress agreed to reconsider its commitment to armed struggle and eventually disband uMkhonto weSizwe, its military wing. Mandela refused to negotiate the use of force until political concessions were made, and Ocalan may do the same.

On Nov. 4, the Turkish state showed its teeth when three Kurdish mayors were removed from their offices and charged with abetting “terrorism.” One of them was the octogenarian Ahmet Turk, a veteran of Kurdish politics, who last year for the third time was elected the mayor of the city of Mardin with nearly 60 percent of the votes. Speaking on Nov. 5, Bahceli honored Turk as a “venerable Kurdish notable.” He implored the removed mayors to “patiently await the result of the judicial process.” Given the weight of MHP cadres in the judiciary, this suggests that the removals were not the last word.

Bahceli nonetheless then reiterated his invitation to Ocalan and held out the prospect of a comprehensive solution, adding that “as taboos are broken and people freely express their views, we can with small steps build confidence and advance from one agreement to another.”

De Klerk similarly said in a speech in 2020 that South Africa’s historic achievement of dismantling apartheid between 1990 and 1994 shows “that we can solve even the most intractable problems when we reach out to one another.”

But in South Africa, the geopolitical backdrop—which was as important for de Klerk as it is for Bahceli in Turkey today—was more favorable. The fall of the Berlin Wall three months before Mandela was freed and the general collapse of Soviet support for South Africa’s enemies along its borders meant that, as de Klerk pointed out in the same speech, that South Africa found itself in a position of relative strength that created a window of opportunity for negotiations.

In contrast, Turkey is mindful that the threats against it have increased, and the PKK and the DEM Party are becoming emboldened by the conflagration in the Middle East, believing that the Kurds across the region stand to benefit from the chaos and have little incentive to tame their aspirations.

Bahceli has shattered the taboos of Turkish nationalism. He has persisted in his overture to Ocalan even in the face of Kurdish militancy and terrorism, but it risks turning into a lost opportunity.

The Kurdish movement will only conclude that it is in its best interest to reciprocate Bahceli’s opening and engage in a confidence-building process with the Turkish state if the United States, whose support for the autonomous PKK region in Syria encourages Kurdish intransigence, decides to invest in a peaceful resolution of the Turkish-Kurdish conflict.

It’s in the interest of the United States that Turks and Kurds make common cause in Syria and beyond. The ball is in President-elect Donald Trump’s court.

0 notes

Text

Events 10.16 (before 1940)

456 – Ricimer defeats Avitus at Piacenza and becomes master of the Western Roman Empire. 690 – Empress Wu Zetian ascends to the throne of the Tang dynasty and proclaims herself ruler of the Chinese Empire. 912 – Abd ar-Rahman III becomes the eighth Emir of Córdoba. 955 – King Otto I defeats a Slavic revolt in what is now Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. 1311 – The Council of Vienne convenes for the first time. 1384 – Jadwiga is crowned King of Poland, although she is a woman. 1590 – Prince Gesualdo of Venosa murders his wife and her lover. 1736 – Mathematician William Whiston's predicted comet fails to strike the Earth. 1780 – American Revolutionary War: The British-led Royalton raid is the last Native American raid on New England. 1780 – The Great Hurricane of 1780 finishes after its sixth day, killing between 20,000 and 24,000 residents of the Lesser Antilles. 1793 – French Revolution: Queen Marie Antoinette is executed. 1793 – War of the First Coalition: French victory at the Battle of Wattignies forces Austria to raise the siege of Maubeuge. 1805 – War of the Third Coalition: Napoleon surrounds the Austrian army at Ulm. 1813 – The Sixth Coalition attacks Napoleon in the three-day Battle of Leipzig. 1817 – Italian explorer and archaeologist Giovanni Belzoni, uncovered the Tomb of Seti I in the Valley of the Kings. 1817 – Simón Bolívar sentences Manuel Piar to death for challenging the racial-caste in Venezuela. 1834 – Much of the ancient structure of the Palace of Westminster in London burns to the ground. 1836 – Great Trek: Afrikaner voortrekkers repulse a Matabele attack, but lose their livestock. 1841 – Queen's University is founded in the Province of Canada. 1843 – William Rowan Hamilton invents quaternions, a three-dimensional system of complex numbers. 1846 – William T. G. Morton administers ether anesthesia during a surgical operation. 1847 – The novel Jane Eyre is published in London. 1859 – John Brown leads a raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia. 1869 – The Cardiff Giant, one of the most famous American hoaxes, is "discovered". 1869 – Girton College, Cambridge is founded, becoming England's first residential college for women. 1875 – Brigham Young University is founded in Provo, Utah. 1882 – The Nickel Plate Railroad opens for business. 1905 – The Partition of Bengal in India takes place. 1909 – William Howard Taft and Porfirio Díaz hold the first summit between a U.S. and a Mexican president. They narrowly escape assassination. 1916 – Margaret Sanger opens the first family planning clinic in the United States. 1919 – Adolf Hitler delivers his first public address at a meeting of the German Workers' Party. 1923 – Walt Disney and his brother, Roy, found the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio, today known as The Walt Disney Company. 1934 – Chinese Communists begin the Long March to escape Nationalist encirclement. 1939 – World War II: No. 603 Squadron RAF intercepts the first Luftwaffe raid on Britain.

1 note

·

View note

Link

By now, the spectacle that is South Africa’s insurrection has been dominating the attentions of just about every political junkie on twitter, drawing the best minds from every corner of the world to bear witness to the fall of the rainbow nation into a predictable quagmire of irresolvable chaos. At home, the pessimism comes in many flavours, and the denialism in many, many more.

The brute facts are now well-known. After dodging prosecution for extreme corruption for over a decade, the former president Jacob Zuma was finally arrested for the relatively minor charge of contempt of court, for not appearing when summoned. While he held out for several days as his supporters (who comprise about half the ruling party including several senior cabinet ministers) picketed outside his palatial compound (bought with the UK foreign aid budget of 2017) and blocked police from entering, he eventually handed himself in. So concluded a long factional battle between Ramaphosa and Zuma that claimed hundreds of lives in burned freight trucks, assassinated councillors, and billions of Rands in legal fees, patronage and PR. Or so it appeared.

On the 8th of July, the president disbanded the Umkhonto weSizwe Veterans Association, essentially the continuation of the old military wing of the ANC, and fiercely loyal to Jacob Zuma. The next day, together with assistance from elements within state intel and security, they deployed to major transport routes, food depots, retail outlets, police stations, power stations, water treatment plants, and ports, to shut down and burn what they could, crippling the Johannesburg-Durban trade artery that carries 65% of our trade volume and half our economic capacity.

After encouraging looting targeting white-owned businesses or “white monopoly capital”, the MK vets could watch as riots burst out to take advantage of the chaos and everything was stripped to the bone by opportunistic looters. In the shadows, organised and disorganised elements blurred together, as even the wealthiest elements of black society got in on the fun of looting, packing luxury sportscars with groceries and appliances before watching the flames tear down the shops and factories.

The police and the military did nothing, and the president was silent, paralysed. Soon the violence spread to the suburbs, and residents cobbled together militia to guard their homes. Proof of address was required to buy groceries. This received wails of agony from the press class and black social media. Slogans calling for the slaughter of Indians (who form a large minority in Durban) and whites became common, and soon the newspapers were joining in on the scapegoating, accusing the citizens’ militia of racism.

…

Everyone here saw this coming, but for decades now, it has been an unacceptable thing to do, to remark upon the inevitable future we find ourselves in. Why it came to all this, and why it matters to Americans and Europeans, is the point of this essay. It will be uneasy to stomach, but it must be swallowed. We live on the brink of barbarism, and the West is following us every step of the way.

A nation may have a lot of ruin in it, but a poor nation has less ruin in it than a wealthy one. When a state collapses or undergoes revolution in the distant reaches of Africa or Asia, there is a certain social distance which prevents Westerners directly apprehending the significance of the social dynamics, the closeness of the dangers, the universality of the lessons, the pain and the tragedy of the loss.

But South Africa is different. South Africa is at once Western and alien to Westerners. Our constitution is Western. Our revolutionaries and our reactionaries and our racial cosmology is Western. Our highest aspiration is that of the West at large – a universal state which recognises no difference of class, race, or creed. And that is why when we observe South Africa, we stare into the abyss of Western civilisation and its global future. Each Westerner sees himself reflected in that void, from the national-socialist, to the anarcho-communist, to the black-nationalist and the bleeding-heart liberal.

And they are right to.

…

Watching any graph of any indicator in South Africa sees every resource drying up, every indicator of health taking a nosedive, and the population booming beyond control, kept in check only by the enormous and perennial pandemic of AIDS and tuberculosis that take many times the number of victims supposedly taken by the SARS-CoV2 virus, every year. We are the rape capital of the world, have seen over half a million homicides since 1994, and the state has not replaced any of the infrastructure built by the Afrikaner nationalist government. The graphs just spell doom in their trend lines, and have for years now, as the Centre for Risk Analysis’s I-told-you-so’s often repeat.

When they came to power, the ruling party was a coalition of communists, black nationalists, organised criminals and common thugs. However, their patrons in the Soviet Union were disbanded, and the Western state apparatus was still composed of law-abiding institutions and competent civil servants. So they purged the minorities, and placed party members at all key posts throughout, to ensure ideological and partisan loyalty – this was called cadre deployment. This crippled the institutions. When the last of the old guard experts were ushered into the wilderness in 1998, they made several systematic departmental reports, which declared the need for replacing infrastructure immediately, to cope with the increased dependent population. This was ignored, largely because the experts were white.

…

While many see the doom as setting in after 1994, it in fact began much sooner. The means by which the ANC gained power was not through civil disobedience, but through a long and sustained campaign of totalitarian violence called the Peoples War, which raged from 1979 until 1993. Black wage increases increased faster than white until this period (51.3% vs 3.8% since 1970), economic growth was over 5%, inequality was falling and blacks enjoyed the highest standard of living of any black population on the continent.

The addiction to cheap black labour meant that industry was irritated with state policies, and in the end, it was the local plutocrats like Harry Oppenheimer and the old secret societies like the Afrikaner Broederbond who opened secret negotiation to end apartheid. And while SA may have had a robust economy once, nothing survived the People’s War. It aimed to “make the country ungovernable”, and largely succeeded. Controlling migration from the black homelands became impossible, and maintaining law and order as the bodies piled up became harder and harder.

…

But the liberal establishment could not bring themselves to believe there were systemic reasons for this state of affairs beyond “corruption” or “inequality”, and the struggle to blame the status quo on the previous regime became ever harder. So they blamed Zuma. The lost decade, they called it. So when Cyril Ramaphosa, a man largely blamed for the Marikana massacre, finally took the party leadership in 2017, after a long, expensive battle of assassination, bribery and skulduggery, he billed himself as a liberal reformer and anti-corruption campaigner, and the international community fell for it hook line and sinker, and local liberals worshipped him like the coming of a new Mandela. He promised the 4th Industrial Revolution. He promised the reigning in of BEE. The Economist endorsed him over the liberal DA.

But he was lying.

…

There are only three sources for non-socialist print media coverage of politics in South Africa. Politicsweb, where all the old senior analysts go when they become persona non grata, the Institute of Race Relations (a venerable old classic-liberal institute with a daily paper, the Daily Friend, and a consulting business, Centre for Risk Analysis), and Maroela Media, an Afrikaans-language publication run by Afriforum, the civil rights activist organisation which sprung from the Afrikaner-national Solidariteit movement.

Aside from this, every other publication leans further to the left than a man with his left leg blown off, and due to a hangover of apartheid-era Cold War politics, “left and right”, terms only applicable among the educated classes, roughly align with a black-vs-white friend-enemy distinction. The Mail & Guardian, for instance (indirectly owned by the Open Society Foundation), has refused to cover any rural homicide committed against a white victim in nearly a decade, despite a global magnifying glass being placed on the barbaric torture and murder spree that has slowly been smouldering across our rural hinterlands. When a white person commits a crime, it is milked dry every day until the journalists get carpal tunnel. But against the ocean of violent depravity committed by the racial majority, which has taken half a million lives since the fall of apartheid, we receive virtual silence. Swaziland, seeing the same kind of violent uprising as KwaZulu Natal is, is treated as a democratic revolution against a tyrannical absolute monarch, despite the opposition being mainly violent communists receiving support from South African parties like the EFF.

…

I was a communist when I was at university. I was delivered a faithful belief in progressivism, nonracialism, revolution and universal democracy, through the national curriculum in South Africa. I was introduced to Marx and Mill as an A Level student in the UK, and when I returned to my native country, I was exposed once more to the poverty and desperation and racial tensions. I assumed all the positions one would expect. More democracy, more repudiation of Christianity and white people, more redistribution, more socialism. But the political waters were calm in those days, and this was mere posturing. Then in 2015 my friends began a campaign to topple the statue of Cecil Rhodes overlooking Cape Town from the university his will founded.

#RhodesMustFall mushroomed rapidly, and became the romantic darling of not only us horny little revolutionaries, but leftists worldwide, who exported the new iconoclasm to Oxford and South Carolina. It is now remembered as #FeesMustFall, a campaign to make tertiary education free (for blacks). But I watched it grow from the inside, and partook in the occupation of admin buildings, touring other college protests in the Cape out of solidarity. But it became clear that it was first and foremost about racial hatred and the purging of Western influence, under their holy trinity of Steve Biko, Franz Fanon and Kimberlé Crenshaw – segregation, national-socialism and a metaphysical racial hierarchy, in new nation called Azania, synonymous with the basketcase fictional nation of Evelyn Waugh’s novel Black Mischief.

This movement, while it began as nonracialist, soon became openly genocidal. Student leaders who called for genocide went unpunished, even praised by the VC of the University of Cape Town. This movement spread to every single university in the country, and despite prominent student leaders praising Adolf Hitler and calling for whites to be swept into the sea, singing genocidal songs at every protest, white students still offered themselves as human shields before police. Dining halls were segregated, classes were violently shut down, nonparticipants in some universities were beaten in their dormitories, staff were chased with buckwhips, buses were burned, paintings were burned, even security guards were burned, and more recently, so was the continent’s largest library. But no big newspaper offered moral criticism, just worries about whether the tactics were effective.

These young people defined a new era, and a new consensus – all struggles are one, and all are about black vs white, and whites must hand over everything and beg for their lives. The only lecturer in the entire country who stood up in public against this cultural revolution was the antinatalist philosopher David Benatar. All others kept their heads down, dithered, or joined the fray, calling for the heads of their less enthusiastic colleagues. Now the Fallists’ ideology is the official pedagogy of the entire university system. But this agitation had been the nature of political life at the poorer “bush colleges” for years now, just without the presence of minority students to trigger resentment or the ideas to build ideology: shut down every exam season to extract more lenient standards and increases in student grants.

And much like the explosion of violence seen at the national level today, South Africa’s poorer areas have been an unremitting hell for all those living in it below a certain class divide. 15% of all women are prostitutes, and the homicide rate is among the highest in the world, and some areas experience permanent civil war level violence. The old apartheid era town planning meant that black areas and minority areas were clearly separated, and this has meant a geographical buffer, where violent protest, which is again among the highest in the world, has largely left the middle classes out of it, even while it occasionally diverts traffic. Protests flare up constantly, as rival factions of the ANC, hamstrung by a corrupt internal promotions process and forbidden from dragging out dirty laundry in public, instead mobilise violent protests to contest wards and civil service posts, often burning down public infrastructure while the mob on the ground chants for “service delivery”.

…

Whatever else Nick Land writes, the lasting impact he had on me was in the very first essay at the opening of Fanged Noumena. He wrote it in 1989, when nobody beneath the highest reaches and darkest recesses of the Atlantic power structure had any awareness that South Africa was about to change forever.

Apartheid still seemed undefeatable to outsiders. The NP had recently smashed the heart of the ANC’s military campaign, creating a bloody hurting stalemate that observers at the time had no expectation would result in any pleasant outcome. Tens of thousands had already been massacred in the Peoples War to give the ANC a monopoly over the black liberation movements, but they seemed to be running out of steam. And so did Pretoria – influx from the Bantustans was unstaunchable, dependence on black labour was firm, and confidence in local cultural hegemony collapsed in 1976.

Nick Land, watching this, noticed something peculiar.

For the purposes of understanding the complex network of race, gender, and class oppressions that constitute our global modernity it is very rewarding to attend to the evolution of the apartheid policies of the South African regime, since apartheid is directed towards the construction of a microcosm of the neo-colonial order; a recapitulation of the world in miniature. The most basic aspiration of the Boer state is the dissociation of politics from economic relations, so that by means of 'Bantustans' or 'homelands' the black African population can be suspended in a condition of simultaneous political distance and economic proximity vis-a-vis the white metropolis. […] My contention in this paper is that the Third World as a whole is the product of a successful - although piecemeal and largely unconscious - 'Bantustan' policy on the part of the global Kapital metropolis.

…

When the British seized the Boer republics in 1900, they drew up the limits of control of the native African tribes where they already lived, and displaced a few thousand of them to tidy up the borders. These eventually became the Bantustans. Immediately, a long slow trickle of immigration was encouraged, not just from the Bantustans, but from British possessions in Asia. The migrant labour created a dense network of diffident ethnicities who demanded fences between them and their neighbours, while attempting to pursue economic exchange.

Black men, who could achieve far greater material wealth from working in the white economy than raising cattle and sorghum in the homelands, flowed steadily into white farmland areas and mining towns. In 1922, the South African Communist Party launched a general strike to demand the enforcement of a colour bar – “CPSA for a white South Africa!”. They were put down in a hail of gunfire by Jan Smuts, the architect of the unitary constitution, which allowed no devolved powers for regional self-governance.

Smuts was a member of Cecil Rhodes’s Round Table club, and shared Rhodes’s ambition to create a grand state where all literate English-speaking men and women south of the Zambezi would have the vote regardless of colour, and all the resources would belong to one grand cartel controlled by a British-American elite of enlightened natural aristocrats. Rhodes used money from his diamond empire and loans from Nathan Rothschild to fund the Jameson Raid and other means to instigate war with the Boer republics, which eventually resulted in the second Boer War and the creation of the Union of South Africa.

…

Smuts, architect of the Union of South Africa, also had a grand philosophy not unlike Nick Land’s – Land treats all matter and life as being ontologically the same, driven by “machinic desires” – all tendencies to motion and behaviour, whether in living or non-living material being fundamentally the same. All matter seeks more complex and integrated forms over time as a result of the force of entropy. Smuts’s grand philosophy, of which he wrote at length in Holism and Evolution, envisaged a means of looking at the world in which all of nature and society could be apprehended and governed as a single holistic system – all organisms, all cultures, all individuals, were destined to evolve into a greater whole, in which each part had its natural place, and that the common teleology of all matter and spirit was the global state, embodied in the League of Nations, the constitution of which he penned himself. Together with his extensive biological knowledge, Smuts and his London interlocutor Arthur Tansley gave birth to the modern systems theory of ecology, and hoped to see a central global technocracy overseeing a holistic ecological management system.

The aims of the United States since the Second World War have some remarkable similarities in approach. The post-war order saw the US employing a philosophy of “defence in depth,” controlling a defensive frontier from the China Sea in the East to the very edge of the Warsaw Pact countries, to ensure freedom of trade throughout this entire region. But this extended beyond military control. The use of embedded CIA operatives meant that those democratic representatives who resisted the grand plans of Atlanticism were swiftly dealt with under insidious operations like Gladio.

…

As these ideas bled into the old left, who were increasingly disillusioned from the failures of the Soviet Union. They turned, as Laclou and Mouffe did, to the notion of using sectional grievances to deconstruct the nation state, leading to the birth of intersectionalism under Kimberlé Crenshaw. The very foundations of nationhood and capitalist Christian civilisation could be toppled if only we united our struggles by leveraging our historical grievances, creating acrimonious divisions in the body politic on the basis of sex, sexuality, race and religion. Thus, the universal loyalties of the nation state that supposedly upheld capitalism would fall, and revolution would arise. This fell right into the plans of the American ruling class.

However, when the social morality of the postwar American colonial project in Europe met the plans of the military and the Malthusian tendencies of the RAND corporation, everything took on a far more ambitious character, with the help of a concept called “environmental security”. The first reference to ES in the sense of protecting the natural environment comes from the US EPA Technical Committee in 1971, as part of an ambitious attempt to quantitatively measure total social wellbeing. This EPA committee was the first to make environmental regulation part of a comprehensive plan for social wellbeing, driven by Holism and cybernetic ecology. They were exceeded in scope by the UN’s 1972 Stockholm Conference, where the idea of “comprehensive” (today, “human”) security emerged, and further, the Palme, Brundtland and Brandt Reports.

…

Under these new umbrella concepts came “human security” and environmental security, the Social Sciences Department of UNESCO and the SSRC found the unifying principles and programs they had sought since the 1950s, and pushed a proselytising program grounded in cross-discipline application of avant-garde ideas to seek “new ways of knowing”, promoting not scientific objectivity, but a synthesis of diverse perspectives. A wholesale transformation of the rules and discipline of social sciences followed, in service of global governance (see the works of Perrin Selcer).

UNESCO even deliberately set about creating a new world religion, in the words of its founder Julian Huxley, and formed the United Religions Initiative, to mould the world’s spiritual beliefs in line with international Anglo progressivism. Feminism and sexual libertinism formed a crowbar against the community cohesion that couldn’t be attacked by means of anti-nationalism, and into this soup of value inversions (erosion of disciplinary distinction, inter-subjectivity [i.e., truth-by-consensus over objectivity], and utopian welfare ideals like “freedom from fear”; “freedom from want”), dropped three wonder pills: Poststructuralism, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Global Warming. Now the great power-narratives of the Atlantic empire were consolidated – Malthus-by-proxy, anti-traditionalism, international diversity-and-inclusion, and the free-trade, open-borders paradigm of the 90’s.

In the same moment as de Klerk gave up on apartheid, the West gave up on the nation state, and handed control to the internationalists, under hegemony of the Atlantic community. A new empire was being consolidated from the territories captured by the Allies in WWII. Thirty years later it is becoming transparent – the new centralised global tax regime has cemented it. Just as the ANC funds the influx of black voters into urban minority areas to build shacks on squatted land, the West welcomes mass migration from the third world, total open-borders, to transform the electoral system against the interests of the native population who might have their own desires, against the grain of global empire. Every corporation and state in the Western world discriminated against whites in hiring. The CIA peddles Critical Race Theory and actively recruits sexual minorities. Colour revolutions can be spotted whenever the rainbow flag or black fist makes an appearance.

Today, the Democratic Party in the US openly looks to South Africa for inspiration in dealing with what Yarvin called the “outer party” – all conservatives are being purged from every institution, in a vast cadre deployment program to ensure the core of the establishment becomes forever untouchable. On the streets they have even begun to use the same tactics for control – deploying huge mobs to destabilise cities when election season is approaching.

Minimum wage rises funnel employment into companies in public-private partnerships with the state, like Amazon, who is part of the Enduring Security Framework partnership of the CIA (which includes Facebook and Google). The analogies between their experimental management strategies and collectivised central-planning are no accident – any company that aims for a total retail monopoly through state-subsidised negative-profit growth is merely another route to total control.

And as the nation and the state are decoupled, the liberal-democratic institutions are being geared toward the concentration of power and wealth, and a strategy of divide-and-rule, to create a cannibal economy. Only a few, like Denmark, have realised what they have gotten themselves into.

…

Much as Aristotle said, a democracy can only function beneficially when steered by the middle class, as it was in Rhodesia and the old Cape, which restricted the vote to property-owners of all races. The middle class’s needs are the core of the productive community, and as Marx observed, they are loyal to the requirements of productive industry and local trade. With the combination of the proliferation of the welfare state and globalisation, the middle class has been whittled away in the West, just as it has here in southern Africa.

Reliance on the state for services means they can’t be sacrificed – in the UK, the NHS has become essentially a religious cult, feeding the civil service, medical contractors, immigrants and the poor alike, in a financially unsustainable way, for decreasing returns. As Philip Bagus observed, the democratic pressures to maintain institutional support via this sort of patronage forces modern western states to take on ever more debt and expand taxation to the limits. This then must be offset by QE, which must be guaranteed by the central state at a rate that benefits the most fragile provinces of any empire so that the whole system does not collapse.

…

What Robert Mugabe did was pursue the universal extension of a first-world welfare state to every peasant in the hinterland, praised by the global left. This required taking on an enormous amount of national debt. Once the IMF tried to impose austerity, Mugabe found this politically unsustainable – his support depended on the handouts, corrupt and legitimate, that he was delivering. So he had to switch to printing money to pay the debts. When inflation became too much to handle, they replaced the core of the economy with dollars, and only elites could survive, much like Venezuela today. As the national treasury ran dry, the military and the civil service became restless. To placate them, they were fed the farms and businesses of the remaining white minority, as well as many areas formerly occupied by black peasants. The state had to cannibalise itself to sustain the predatory ruling class.

During this time, Mugabe attempted to control every aspect of the environment and economy through price and capital controls, suffocating every aspect of social life with red tape. It only accelerated the process. While the vast global network of UN subsidiaries extract compliance from the US client states

In South Africa today, the state coffers are empty. Even the ruling party is feeling it, as their headquarters Luthuli House was attached by the court to pay for a crooked PR contract they refused to deliver on. We have since taken out an IMF bailout, which is being poured into infrastructure, mostly Durban’s port, which is now choked by smoke and looting. Our president’s advisors are pushing for land reform, and remarkably, one of them, Ruth Hall, was advising Robert Mugabe how to liquidate his pale kulaks back in 2002. Other advisors, like Thembeka Ngcukaitobi, call for the fulfilment of the genocidal prophecy of Makhanda, and have whites deprived of all land and all moveable and liquid assets. This is deliberate Zimbabwefication.

The same economic dynamics are present in the world at large – the share of GDP spent on welfare keep increasing, as does the debt-GDP ratio. Capital formation has been falling for decades, and chronic inflation is treated as a static phenomenon, which nobody dares reign in, because the entire system is dependent on low interest rates to keep the constant corrosive consolidation of the global market going full steam ahead. This arrangement results in the inflation of property prices as along term hedge against inflation which, when the plebs followed suit resulted in the 2008 bubble, when they tried to play the elites’ asset accumulation game with borrowed money.

…

What has America been doing these past 18 months? It has been printing money so fast that it has kept pace with the plummenting Rand, and allowed Cyril Ramaphosa to tell investors that his economy is relatively strong – the Rand has “stabilised”. Error of parallax. Nor is it even just America printing money. While they certainly can afford to, as the holders of the world’s reserve currency, China is attempting to do the same, only they are directly funnelling the cash into commodities, rather than spreading it around a financial elite over which they have minimal control.

And yet their leverage is far worse than America’s – Kyle Bass, who has been shorting the Chinese market for years now, insists that the historically unprecedented levels of leverage in the Chinese economy are unsustainable, and that they cannot, even under miracle conditions, correct their shrinking population trends sufficiently to turn this ship around. But what many forsee in dreams of revolution and revolt, the breakups of massive crumbling empires, is not going to happen as they hope.

Instead, the state will protect the stability of the ruling class and its control over the levers of power at the core, bleeding everyone dry and terrorising them into submission. What happened to Zimbabwe is a warning, but it only happened the way it did because half the population could leave and send home remittances. The iron fist of a “democratic” government capable of rigging its elections and gagging the press and the courts is only as tyrannical as the cost of a bus ticket to the next country. After 900-member Zoom calls and election “fortification”, I shouldn’t need to gild the lily any more.

As many observers of China remark, an economic collapse of a country of its nature will not result in a breakup or a massive reform, but in the shrink-wrap tyranny of North Korea, an eternal sclerotic stagnation, fed by government dependency, held in place by state security. The West is losing control of its ability to provide the kind of total state security required for this however, and has been reaching for a far more sinister method of control – the financial system.

And this is where all analogies break down, because what is about to happen here is unprecedented. The international Bank of Settlements has recently announced that they intend to use Central Bank Digital Currency to control the spending of all global citizens, and have the tech and the power to control each and every expenditure, and to shut anybody out of the ability to feed themselves if they so choose. But this movement to kick away the ladder and consolidate total control follows the same logic as Zimbabwe’s – the poor can only be fed for so long, but the ruling elite must be fed forever, or else the whole house comes down.

…

The twin systems of China and Atlantis are both attempting to consolidate total control over their economic and social environment. And in order to achieve the kind of reforms that he wishes to, Ramaphosa has reached for the help of both power blocs. China has colonised our northernmost province, and receives special treatment from law enforcement that must learn Mandarin. Chinese are registered as black, to benefit from the racial privileges blacks enjoy under Black Economic Empowerment. While the government’s reports usually look like a dog’s breakfast, their reports on the UN sustainable development goals are always crisp, professional, and detailed. SDG 10 justifies the expropriation of property, according to their logic.

…

The erosion of the middle class, the working class, the institutions of law and order and even the substance of the informal economy was dry tinder to the Zuma-faction’s firebrands. To fulfil his mandate to end corruption, Ramaphosa had begun prosecutions proceedings into the Zuma faction – tentatively of course, since any too-wide-ranging investigation would unearth the corruption of all. But lawfare isn’t enough. They were cut out of party patronage systems as big figures like Ace Magashule were expelled from the party. Judges ruled that the state would not cover their defence costs anymore.

When the Umkhonto we Sizwe veterans association was disbanded and cut off from “pension” money, they finally put into action something that they would have had up their sleeve for months. Police armaments caches had been going missing for months. Firearms training for youths had been going on at the local branches for years. Every storage depot and major highway was targeted, petrol stations, power stations, water treatment plants were hit. They needed to make the country ungovernable, and they did. But this time they didn’t have the support of the Swedish, the Russians or anybody else.

Complicit elements are even inside the SSA, our central intelligence agency. What it will take for Ramaphosa to clear the state and party of seditious elements will give him the power of a modern dictator, cheered on my the press and everybody else, who despises Zuma and his people for what they’ve wreaked upon us. But with three months left of military deployment, all of the military capacity in one province, and the president fearing wielding lethal force on black mobs for fear of his Marikana ghosts coming back to haunt him, the rebels have three months to decide whether to act.

That leaves three months to see whether we become a black-nationalist disctatorship, or a new Yugoslavia. The Zulu, who form the backbone of the rebellion, have cheered for Zulu independence before, though their forces are split – the Zulu nationalist/traditionalist party the IFP have stood firmly against this chaos. Zuma’s people are still pushing black identity over tribal. Zuma may have been a traditionalist, a defender of the Swazi royal house when in crisis, an expander of chieftains’ rights, but his time in head of the ANC death squads in Zululand in the 1990s makes Zulu solidarity impossible.

So chaos it is.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apartheid

Apartheid, or “apartness” in the language of Afrikaans, was a system of legislation that upheld segregation against non-white citizens of South Africa. After the National Party gained power in South Africa in 1948, its all-white government immediately began enforcing existing policies of racial segregation. Under apartheid, nonwhite South Africans—a majority of the population—were forced to live in separate areas from whites and use separate public facilities. Contact between the two groups was limited. Despite strong and consistent opposition to apartheid within and outside of South Africa, its laws remained in effect for the better part of 50 years. In 1991, the government of President F.W. de Klerk began to repeal most of the legislation that provided the basis for apartheid.

Racial segregation and white supremacy had become central aspects of South African policy long before apartheid began. The controversial 1913 Land Act, passed three years after South Africa gained its independence, marked the beginning of territorial segregation by forcing Black Africans to live in reserves and making it illegal for them to work as sharecroppers. Opponents of the Land Act formed the South African National Native Congress, which would become the African National Congress (ANC). Did you know? ANC leader Nelson Mandela, released from prison in February 1990, worked closely with President F.W. de Klerk's government to draw up a new constitution for South Africa. After both sides made concessions, they reached agreement in 1993, and would share the Nobel Peace Prize that year for their efforts.

The Great Depression and World War II brought increasing economic woes to South Africa, and convinced the government to strengthen its policies of racial segregation. In 1948, the Afrikaner National Party won the general election under the slogan “apartheid” (literally “apartness”). Their goal was not only to separate South Africa’s white minority from its non-white majority, but also to separate non-whites from each other, and to divide black South Africans along tribal lines in order to decrease their political power. The Population Registration Act of 1950 provided the basic framework for apartheid by classifying all South Africans by race, including Bantu (Black Africans), Coloured (mixed race) and white.

A fourth category, Asian (meaning Indian and Pakistani) was later added. In some cases, the legislation split families; a parent could be classified as white, while their children were classified as colored. A series of Land Acts set aside more than 80 percent of the country’s land for the white minority, and “pass laws” required non-whites to carry documents authorizing their presence in restricted areas. In order to limit contact between the races, the government established separate public facilities for whites and non-whites, limited the activity of nonwhite labor unions and denied non-white participation in national government. Hendrik Verwoerd, who became prime minister in 1958, would refine apartheid policy further into a system he referred to as “separate development.” The Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act of 1959 created 10 Bantu homelands known as Bantustans. Separating Black South Africans from each other enabled the government to claim there was no Black majority and reduced the possibility that Blacks would unify into one nationalist organization.

Every Black South African was designated as a citizen as one of the Bantustans, a system that supposedly gave them full political rights, but effectively removed them from the nation’s political body. In one of the most devastating aspects of apartheid, the government forcibly removed Black South Africans from rural areas designated as “white” to the homelands and sold their land at low prices to white farmers. From 1961 to 1994, more than 3.5 million people were forcibly removed from their homes and deposited in the Bantustans, where they were plunged into poverty and hopelessness. Resistance to apartheid within South Africa took many forms over the years, from non-violent demonstrations, protests and strikes to political action and eventually to armed resistance.

Together with the South Indian National Congress, the ANC organized a mass meeting in 1952, during which attendees burned their pass books. A group calling itself the Congress of the People adopted a Freedom Charter in 1955 asserting that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, Black or white.” The government broke up the meeting and arrested 150 people, charging them with high treason. In 1960, at the Black township of Sharpeville, the police opened fire on a group of unarmed Black people associated with the Pan-African Congress (PAC), an offshoot of the ANC. The group had arrived at the police station without passes, inviting arrest as an act of resistance. At least 67 people were killed and more than 180 wounded.

The Sharpeville massacre convinced many anti-apartheid leaders that they could not achieve their objectives by peaceful means, and both the PAC and ANC established military wings, neither of which ever posed a serious military threat to the state. By 1961, most resistance leaders had been captured and sentenced to long prison terms or executed. Nelson Mandela, a founder of Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”), the military wing of the ANC, was incarcerated from 1963 to 1990; his imprisonment would draw international attention and help garner support for the anti-apartheid cause.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Assata Shakur

Assata Olugbala Shakur (born JoAnne Deborah Byron; July 16, 1947), whose married name was Chesimard, is an activist, member of the left-wing Black Liberation Army (BLA), who was convicted of murder in 1977. She escaped from prison in 1979 and fled to Cuba in 1984, gaining political asylum.

Between 1971 and 1973, Shakur was charged with several crimes and was the subject of a multi-state manhunt. In May 1973, Shakur was involved in a shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike, in which New Jersey State Trooper Werner Foerster was killed and Trooper James Harper was grievously assaulted; she was charged in these attacks. BLA member Zayd Malik Shakur was also killed in the incident, and Shakur was wounded. Between 1973 and 1977, Shakur was indicted in relation to six other incidents—charged with murder, attempted murder, armed robbery, bank robbery, and kidnapping. She was acquitted on three of the charges and three were dismissed. In 1977, she was convicted of the first-degree murder of Foerster and of seven other felonies related to the shootout.

Shakur was incarcerated in several prisons in the 1970s. She escaped from prison in 1979 and, after living as a fugitive for several years, fled to Cuba in 1984, where she received political asylum. She has been living in Cuba ever since. Since May 2, 2005, the FBI has classified her as a domestic terrorist and offered a $1 million reward for assistance in her capture. On May 2, 2013, the FBI added her to the Most Wanted Terrorist List; the first woman to be listed. On the same day, the New Jersey Attorney General offered to match the FBI reward, increasing the total reward for her capture to $2 million. In June 2017, President Donald Trump gave a speech cancelling the Obama administration's Cuba policy. A condition of making a new deal between the United States and Cuba is the release of political prisoners and the return of fugitives from justice. Trump specifically called for the return of "the cop–killer Joanne Chesimard."

Early life and education

Assata Shakur was born Joanne Deborah Byron, in Flushing, Queens, New York City, on July 16, 1947. She lived for three years with her mother, a school teacher, her Aunt Evelyn, a civil rights worker, and retired grandparents, Lula and Frank Hill. In 1950, Shakur's parents divorced and her grandparents moved to Wilmington, North Carolina, where she then spent most of her childhood with younger siblings, Mutulu and Beverly. Shakur moved back to Queens with her mother and stepfather after elementary school, attending Parsons Junior High School. However she still frequently visited her grandparents in the south. Their family struggled financially, and argued frequently, so Shakur was rarely ever home, exploring the street life. She often ran away, staying with strangers and working for short periods of time, until she was taken in by her aunt Evelyn to Manhattan. Here, Shakur underwent personal change. She has said that her Aunt Evelyn (Williams), her mother's sister, was the heroine of her childhood, as she was constantly introducing her to new things. She said that her aunt was "very sophisticated and knew all kinds of things. She was right up my alley because I was forever asking all kinds of questions. I wanted to know everything." Much of her time with Evelyn was spent in museums, theaters, and art galleries, and the conflicts that did rise between the two were typically due to Shakur's habit of lying.