#thank you to my colleague charlie who's gonna teach me how to play it with his friend

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I FINALLY FOUND SOMEONE TO PLAY SEA OF THIEVES WITH

#thank you to my colleague charlie who's gonna teach me how to play it with his friend#i was begging my girl gamer bff to play w me forever but she said no#BUT FINALLY I GET TO LIVE OUT MY PIRACY DREAMS#“you might have to carry me while i learn” “oh that's totally cool”#they sing sea shanties???? bitch i know so many sea shanties i'm in for the ride#ooc

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dead Poets Society: The Story

Dead Poets Society opens in a pretty traditional way: with the first day of school.

It’s the beginning of a fresh school year for transfer student Todd Anderson (Ethan Hawke), new, shy kid on the block at Welton Academy, a prestigious prep-school for boys, located in Vermont. At the opening ceremony, older recruits march through a church, down the aisles full of other students, carrying banners that display the words: Tradition, Discipline, Honor, and Excellence. New students light candles, and, most importantly, headmaster Nolan takes to the podium to welcome the new students, and shy, quiet Todd Anderson sits in the pew, looking nervous as Headmaster Nolan begins his speech, discussing the four Pillars of the school, the prestigious nature of the establishment, and introducing the new English teacher: John Keating (Robin Williams).

The panel of teachers, sitting behind Nolan, is notably older and grayer than Keating, who, while not a terribly young man, is considerably more lively and animated than his new colleagues. This will be important later, but not right now. (Spoilers below!)

After the ceremony, the courtyard in front of the school is full of parents saying goodbye to their sons. It is here that we learn something interesting about Todd: he has, as Nolan puts it, “big shoes to fill” . As it turns out, Todd’s older brother was a student here, and a pretty good one. Even more nervous, Todd files out of the courtyard with the rest of the students, where we meet Todd’s to-be roomate: Neil Perry (Robert Sean Leonard).

Neil Perry seems to be Todd’s complete opposite in personality. He’s confident, and out-going, and is expected by Nolan to be doing ‘great things’ this year. He takes Todd up to their dorm room, and there, Todd meets Neil’s friends: Knox Overstreet (Josh Charles), Richard Cameron (Dylan Kussman), Stephen Meeks (Allelon Ruggiero), Gerard Pitts (James Waterson), and Charlie Dalton (Gale Hansen). The boys get comfortable in Neil and Todd’s room, teasing Neil for being made to take chemistry courses over the summer. The laid-back nature of the introductions is cut short, however, by a knock at the door.

It’s Neil Perry’s father (Kurtwood Smith).

Mr. Perry tells Neil that he has spoken to Mr. Nolan, and has cut all of Neil’s extra-curricular activities for the year, including the school yearbook, as he doesn’t want Neil distracted from the end-goal of medical school. Neil tries to argue, but is quickly shot down.

After Mr. Perry leaves, the other boys encourage Neil to stand up to his father, but he refuses, resigned to doing what he’s told. The other boys leave, inviting Todd to join them for a Latin study group the next day.

The next day, on the first true day of classes, the boys pass through lesson after lesson, taught by wizened, distinguished men who bore their students to tears.

And then comes English class.

Mr. Keating enters the room, passes his entire classroom, and heads for the opposite door, telling his class to follow him. Confused, the class obeys.

Keating takes them out to the hallway, encouraging them to look at the case full of pictures of Welham alumnus, and tells them that those who first attended Welton, explaining that these people who were once young, are now old, or even dead.

“Carpe diem, seize the day. Gather ye rosebuds while ye may.”

He also recites to them some poetry:

“O Captain, my Captain. Who knows where that comes from? Anybody? Not a clue? It’s from a poem by Walt Whitman about Mr. Abraham Lincoln. Now in this class you can either call me Mr. Keating, or if you’re slightly more daring, O Captain my Captain.”

After class, Cameron remarks that Keating seems rather odd, but the rest of the boys seem to like him, or at least, find him interesting. While the boys hit the showers, Knox reveals that he has to attend a dinner at the Danburys’ (whoever they are, more on that later) explaining that he can’t meet to study with them tonight. The boys pick on him a little and then invite Todd, who doesn’t seem to be on board for the plan.

That night, the boys meet to study, and Knox comes in late, elated. See, he’s met the most beautiful girl he’s ever seen: Chris. The bad news is that she’s engaged to a guy named Chet, but that doesn’t seem to deter Knox that much. He remains completely smitten.

The next day, Keating’s class remains as unconventional as the day before. This is no course where the first class is fun and then it’s down to business the next day: Keating seems to mean business about seizing the day.

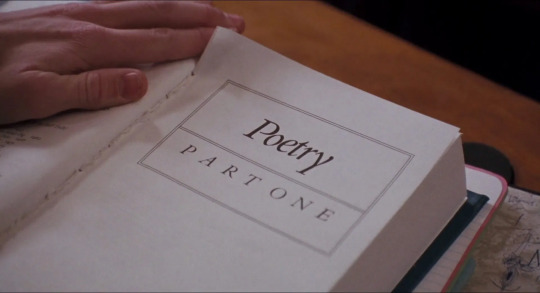

He opens class by requesting that Cameron reads the first page of the introduction of their poetry book, an introduction about how to rate a poem’s ‘greatness score’. As he reads, Keating writes on the board, allowing him to reach the end of the page before telling Cameron, and the rest of the class, to rip out the introduction.

At first, the class hesitates, but after a moment, many of the students gleefully obey. As they tear out the pages, another teacher, Mr. McAllister stops to investigate. Keating explains that he is teaching the boys to think for themselves, to enjoy the use of language and the power of words.

“No matter what anybody tells you, words and ideas can change the world.”

The boys contemplate this as Keating adds:

“We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for. To quote from Whitman, “O me! O life!… of the questions of these recurring; of the endless trains of the faithless… of cities filled with the foolish; what good amid these, O me, O life?” Answer. That you are here – that life exists, and identity; that the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse. That the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse. What will your verse be?”

At dinner, McAllister sits next to Keating and chastises him warningly about his choice to educate the boys to think for themselves, encouraging them to be creative.

“Show me the heart unfettered by foolish dreams and I’ll show you a happy man,” McAllister quotes.

Keating smiles and replies with a verse of his own: “But only in their dreams can men be truly free. ‘Twas always thus, and always thus will be.”

At their own table, the boys unearth an old yearbook, searching for Mr. Keating’s page. They learn that he was involved in a group called the ‘Dead Poets Society’.

Curiosity piqued, the boys ask Keating about the Dead Poets Society after dinner. Keating explains that it was a secret society, inspired by the words of Henry David Thoreau to ‘suck the marrow out of life’. This group would gather in a nearby cave and read poetry aloud, and write some of their own.

Neil suggests to the rest of the boys in private that they should revive the Dead Poets Society and meet that night. In his room, he finds a book called Five Centuries of Verse, with an inscription from Keating: the opening to every Dead Poets Society meeting.

“I went to the woods because I wanted to live deliberately. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life. To put to rout all that was not life; and not, when I had come to die, discover that I had not lived.”

That night, the boys all sneak out of the school and meet in the caves. Neil begins the meeting, reading the opening, and then the group takes turns reading poems and talking, getting progressively more spirited. After a while, they conclude, heading back to the school and singing.

The next day, in English class, Mr. Keating shows the boys how to read Shakespeare: not dull and stuffy, but full of life, (doing impressions of Marlon Brando and John Wayne to illustrate) and then does something even stranger.

Keating climbs onto his desk and asks the class why he does this. Charlie suggests that it is to feel taller.

“No! Thank you for playing, Mr. Dalton. I stand upon my desk to remind myself that we must constantly look at things in a different way.”

With that, Keating encourages his class, one at a time, to stand on his desk, looking at the room from a different perspective. As class comes to a close, Keating announces that the boys are to write, and then read aloud, their own poems, privately telling Todd that he is quite aware how much this assignment must scare him.

In his room, Todd attempts to write a poem as Neil bursts in, full of excitement. He has discovered a flier for a community play of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and intends to try out, realizing that he wants to be an actor. He says:

“For the first time in my whole life, I know what I wanna do! And for the first time, I’m gonna do it! Whether my father wants me to or not! Carpe diem!”

The next class, Keating takes the boys out to the field, handing them each a line of poetry. He begins an exercise where each boy must read aloud the line before running up and kicking a ball, one after another, while he plays classical music. Directly after, Neil blazes through the dorm, shouting that he’s secured the part in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, his enthusiasm undaunted by the fact that his father will never write the approval letter necessary. He forges the necessary letter from his father for the theater and the school principal as Todd looks on.

It is the next English class, and it is time to read the poems from the class. Knox, who has ridden his bike to Chris’s school to watch her at least once, reads aloud a poem dedicated to her. Other students read, and finally, it comes time for Todd’s turn.

Todd, as it turns out, hasn’t written a poem.

Undaunted, Keating brings Todd to the front of the class, covering his eyes and encouraging him, helping him create a poem on the spot. Todd’s spontaneous poem brings the class to applause, and Mr. Keating moves the class outside for some more ‘poetry in motion’.

At this point in the story, we’ve got a lot of information about quite a few characters.

Protagonists Todd and Neil, originally apparently the opposites of one another, are similar in pressures from home: Todd to be like his older brother, and Neil to follow the carefully laid plan that his father has set out for him. Neil is already moving outside of that plan, pursuing acting, and Todd, with some encouragement, manages to come up with an intense poem in front of an entire class, despite his shyness.

Even the other boys in the group have unique characterization: Charlie, the anything-for-a-joke class clown, Knox, the hopeless romantic, and Cameron, the reluctant tag-along. (Meeks and Pitts are there too, but they have far less screen time and personality than the rest of the DPS.) We as an audience are watching their growth and personal arcs after the catalyst that is John Keating.

Oddly enough, Keating is the main character that we spend the least amount of time with, and know the least about. We don’t know a lot about his home life, or what his background is, or what his thoughts are. All we see is his direct influence on the boys at the school, and his unintentional inspiration to restart the Dead Poets Society.

Speaking of which:

At the next Dead Poets Society meeting, Knox seems uneasy, announcing that he’s going to kill himself if he can’t be with Chris, and leaves the meeting to call her. The boys follow, cheering him on, as he makes the call, hanging up at first, before working up his nerve (Carpe Diem) to call her again. Chris invites Knox to a party, saying she was thinking about calling him, and elated, Knox accepts the invitation.

The next night is the night of the party. Knox heads off to the Danbury house, where he’s swallowed up by a rowdy crowd of teenagers. Soon enough, Knox (and everybody else) is at varying levels of intoxicated. Inhibitions loosened, Knox kisses the forehead of a passed-out Chris, enraging her boyfriend and starting a fight, ending the party abruptly.

Meanwhile, Todd is given the exact same birthday present as last year: a desk set that he didn’t even like, yet another sign of his parents not really paying attention to him. Neil, noticing Todd’s disappointment, cheers him up, throwing the desk set off the roof, before taking him to another Dead Poets Society Meeting, where Charlie (now insisting on being called Nuwanda) has brought girls in to impress them with poetry.

Charlie also announces that he published an article in the school newspaper demanding that girls be admitted to Welton, signing it the Dead Poets Society. The rest of the group is justifiably angry, afraid that this will put the school’s administration onto them.

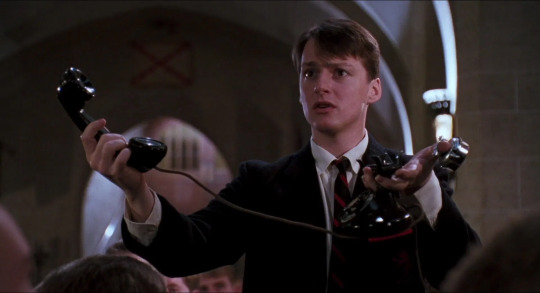

Sure enough, at an assembly, Headmaster Nolan demands to know which of the students was responsible for the article. At first, none of the students come clean, until a phone rings.

Charlie picks it up, and announces that it’s from God, saying they should admit girls to Welton.

This prank inevitably ends with Charlie getting paddled in the Headmaster’s office (1959, remember?) and threatened with expulsion. Nolan wants the names of the other members of the Dead Poets Society, but Charlie won’t tell.

After dismissing Charlie, Nolan calls Keating in, questioning him about his teaching methods. Keating explains that he’s trying to teach the boys individualism.

“I always thought the idea of education was to learn to think for yourself.”

“At these boys’ age? Not on your life!”

Afterwards, Keating approaches the boys, specifically Charlie, and gently scolds him for his stunt.

“There’s a time for daring and there’s a time for caution, and a wise man understands which is called for,” he says, explaining that being stupid is not the same as being an individual.

This is a common theme of the entire story, actually. As much as Keating encourages free-thinking and exploration of ideas, he knows the difference between bucking authority for the sake of it versus nonconformity. Each of the boys is exploring this aspect in their own way, from Todd’s slow-growing confidence to Neil’s direct disobedience of his father’s oppressive plan to Charlie’s defiance, even to Cameron’s caution against ‘disobeying rules’. Dead Poets Society is a story about encouraging people to think for themselves, but to be wise about what they do once they start, and while some are more obvious than others (Charlie’s foolishness and Knox’s overzealousness contrasted with Cameron’s blind following of ‘the rules’, all portrayed as kind of problematic), some examples are more ambiguous.

Such is the case with Neil.

After a rehearsal for the play, Neil comes back to his dorm to find his father, very displeased with him. He’s incredibly angry about Neil joining the play, and instructs him to quit the play the next morning, the same day as the first performance. Upset, Neil goes to Mr. Keating’s office to ask him for advice.

Keating listens to him, and suggests trying to talk to his father, for Neil to show him how passionate he is about acting so that he will allow him to do the play, encouraging him to come to his father earnestly before the play.

On a slightly lighter note, Knox enters Chris’s high school and follows her to class with flowers, trying to apologize for the previous night. She’s understandably embarrassed and tells him that her boyfriend, Chet, is still upset with Knox and is out to get him. Undeterred, Knox follows her into class and reads a poem about Chris aloud, in front of all of her classmates.

Remember what I said about ‘wise’ ways to deal with free thinking?

A little later, Neil lies to Keating, telling him that he’s talked to his father, and that he’s allowed to stay in the play.

The next night, Keating and the boys prepare to go see Neil perform, with Chris even turning up and deciding to accompany Knox to the play. It’s well worth it. Neil is in his element, comfortable and dynamic on stage, and his classmates and teacher cheer him on, awestruck by his talent.

Before the last monologue, Neil spots his father, entering the theater. Clearly daunted, he goes out and sells his final monologue anyway, to the wild applause of the audience.

All but his father.

After the performance, Neil’s father brings him home, informing him that he is being pulled out of Welton, and enrolled into a military school, immediately followed by medical school. Neil attempts to argue, to plead his case, but his father shuts him down, and Neil stops arguing.

Later that night, after his parents go to bed, Neil sneaks into his parents’ room wearing his costume, opens the drawer, taking his father’s gun, before retreating to his father’s study and killing himself.

It is right here that the movie goes from a good, even average film about ‘seizing the day’ and living life to the fullest, to a great movie about the consequences of doing it.

In another movie, Neil’s father would have seen the performance and realized his son was right. Or if he hadn’t, Neil would have finally stood up for himself, and his parents might have seen the light.

In another film, Neil wouldn’t have died. Especially not like that.

It is this moment, this gear-switch, that the audience is forced to contend with the implications, the fallout of these actions, and that sometimes, even ‘seizing the day’ is impossible, depending on your circumstances.

It’s not an easy idea to swallow. It’s not one we’re used to in movies. But it’s here, nonetheless.

Back at Welton, the boys tearfully wake Todd up to tell him the news. Upset, Todd runs out into the snow, as the boys follow. He remarks on how beautiful the snow is before throwing up and breaking down, rushing into the snow alone. In the classroom, Mr. Keating paces empty desks, arriving at Neil’s and removing the poetry book he left for him with the Dead Poets Society inscription.

The next morning, it turns out that the fallout affects more than Neil.

Headmaster Nolan announces that he intends to conduct an investigation into what happened. The boys gather to talk as Nolan interrogates Cameron, the rule-abider. The remaining Dead Poets are certain that Cameron is going to sell them out, and sure enough, that’s exactly what he does. Cameron enters, telling the group that he told them everything, and that they all should too, as it’s too late to save Keating, but not to save themselves.

Charlie reacts to this by punching Cameron in the face, getting him expelled.

The next boy called in is Todd, who enters Nolan’s office to find his parents there, too. Nervously, he sits as Nolan tries to get Todd to sign a document blaming Mr. Keating for Neil’s death. Todd glances at the page: the rest of the Dead Poets have signed too.

Later, in English class, Headmaster Nolan arrives and announces that he will be teaching until they can find a permanent replacement for Keating. As he opens class (encouraging people to read the ‘excellent’ ripped out introduction from the book) Keating enters the room to collect his things. After long moments of silence of the boys keeping their heads down as Keating gathers his belongings, Todd finally breaks, calling out to Mr. Keating and telling him that the school forced them to sign the confession.

As Nolan tries to get him to sit down, Todd shouts out: “O Captain, My Captain”, and stands on his desk. Many other students follow, one by one, as Keating tearfully watches.

Keating gratefully thanks the boys, and the film ends on a closeup of Todd’s face, after he’s finally stood up for himself, and seized the day.

Make no mistake, this is not a happy ending. Keating is forced to leave the school. Neil has taken his own life, trapped into a lifetime he didn’t want. Charlie has been expelled, and it’s likely the rest of the boys will be too. This is a movie based on, and ending with, great uncertainty. Not every boy stood up. Not everyone is coming out of this okay.

The question is, what are we supposed to take away from this?

The message of the film, the core theme that people remember, is Seize the Day. And yet, of those who ‘Seize the Day’, very few come out of it unscathed, if any. Instead, people are left with heartbreak, making bad decisions or, even if the decisions may have been morally ‘right’, or what they felt they had to do, consequences must follow. Charlie’s overzealous sense of humor and bucking of authority gets him expelled. Knox’s over-the-top romanticization of Chris nearly drives her away and gets him in trouble. Neil kills himself because the restricting nature of his family won’t allow him to ‘Seize the Day’.

And Todd?

Todd finally speaks out, but too late to fix any of the damage.

Despite the focus on Mr. Keating in most of the promotional material, the protagonist of the movie is, of course, Todd. Once Neil dies, Todd is who we are left with, and it is Todd who changes from shy boy who won’t speak out to the leader of a final daring farewell to a teacher that changed his life. He’s the one that grows. He changes.

It’s just too little too late.

The story of Dead Poets Society is a sobering one, and not exactly a story you’d expect. The first two-thirds could have been part of any typical, ‘feel good’ teen drama about self-discovery, but the last third takes expectations and turns them on their head. This is real life: it doesn’t always work out. People get fired for trying to do the right thing. Parents don’t see the harmful impact they have on their children. People value rules and tradition over the dreams of the young.

It is in this devastating third act that Dead Poets Society earns its place as a classic: by refusing to allow the cliched beginnings to define its ending.

It would have been so easy to allow Neil to convince his father to allow him to act. It would have been simple to allow Keating to change the mind of the establishment, for the Dead Poets to take Welton by storm.

But real life doesn’t always work out like that. Sometimes, the way we go about ‘seizing the day’ can end badly depending on our circumstances and the wisdom in the method we choose. The film isn’t telling us how to do it right. It’s showing you the lives of people who did it wrong, or at least, who seized the day, tried to make their lives extraordinary, and failed, due to many different reasons.

But.

That doesn’t mean we should stop trying.

For every failure, for every mistake (Neil sneaking to do the play, Charlie’s pranks, etc.), Todd’s example stands above and beyond. Yes, he might get into trouble. But this moment, this act of telling a beloved teacher that his work was not in vain, that his students will remember him, that he was not to blame, feels right. This is what he is supposed to do.

We cheer for that moment, we feel the weight of the movie lift just a smidge, because in the end, we have to seize the day. We have to try to make our lives extraordinary, but we have to find the right way to do it, the wise way to do it.

Because, for all of the mistakes made, Keating is right: Words and ideas will change the world. It is up to us how to use them, when to use daring, or caution, and in the end, try to find the meeting place between doing what is right, and doing what is true to yourself.

The ending is uncertain, yes. But it’s the only satisfying ending that an honest movie could give us.

Dead Poets Society is an emotional story, bringing up questions about non-conformity and following the rules that go beyond a surface: ‘yes or no’. A gripping story full of great performances, a warm atmosphere, and immortal dialogue, Dead Poets Society will continue to be a testament to words as long as we care to use them.

In the articles ahead, we’re going to be taking a look at some of the other important elements of Dead Poets Society, so if you enjoyed this one, stick around and join us! Don’t forget to leave a comment, like, or some other form of love if you enjoyed it, and follow for more! Thanks so much for reading, and I hope to see you in the next article.

#1989#80s#Dead Poets Society#Dead Poets Society 1989#Comedy#Drama#Dylan Kussman#Ethan Hawke#Film#Gale Hansen#Josh Charles#Kurtwood Smith#Movies#Peter Weir#PG#Robert Sean Leonard#Robin Williams

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Baghdad to Iwo Jima, an anthem for the dead

Two Marines — one a veteran of Iraq and the other a survivor of Iwo Jima — remember the fallen and weigh the meaning of a national anthem.

Abner Greenberg doesn’t look like someone who was shot in the head on Iwo Jima.

At 93, he’s stockier and more solid than any nonagenarian I’ve met. The skin on his forehead and cheeks is smooth and has a healthy glow, and despite being mostly bald, his head bears no evidence of the Japanese bullet that went through the left side of it, leaving him unconscious for weeks and confused for months, unable to access his own speech.

When I shake his broad, meaty hand, I cannot tell that he hasn’t had feeling in his right arm for the last 73 years. He cannot button a shirt; his wife, Marilyn, helps him get dressed every day. “That’s the fun with us,” he says with a grin.

His aphasia is another result of the bullet that entered his head, but I don’t recognize that he’s using almost exclusively pronouns instead of proper names until he points it out himself. He is lively and sharp, easily the envy of men two decades younger.

Iwo Jima is familiar to most Americans thanks to a John Wayne movie and the famous photo of the flag-raising on Mount Suribachi, which is immortalized at the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Va. It was a battle so fierce and horrifying it shocked even the battled-tested veterans of a country in its fourth year of world war.

Of the 82 Medals of Honor awarded to Marines during the entirety of World War II, 27 of them were for actions on Iwo Jima; of those, more than half were awarded posthumously. The island was death itself.

Imagine eight square miles where 29,000 lives ended in just 36 days.

Imagine: Somewhere in the vast Pacific Ocean is eight square miles of volcanic ash where nearly 29,000 lives ended in just 36 days. Greenberg was one of nearly 20,000 more who suffered a casualty but survived. Iwo was his fourth amphibious landing in 13 months, and he’s still shaken by the horror unleashed on the first day when 2,400 Americans were killed or injured. Two of them were the best friends he’d ever known. “We hung around together, y’know? We just … talked. ‘We’re gonna survive this thing,’ et cetera, et cetera.

“Well, we got off of the beach, and we had a spot … I got down with these two other guys, and all of a sudden it started lighting up. It got into the late afternoon and evening, and mortars were hitting us.”

This is how combat stories are told, by the way. Hours of terror and stress that shatter lives get compressed to a sentence in the service of a more interesting narrative.

“We got hit by mortars, all three of us. And, uh—” His voice wavers. “I got to Barney. Barney Aloysius Cochrane, who was my best friend, my leader, everything that I needed to get through what I went through … and I just couldn’t leave him for that moment. He was dead. I was shaking all over, and I was crying. And frozen, absolutely frozen.

“And then I realized that someone was moaning, and it was Schultz. George Andrew Schultz.” He pauses. A long pause. “I couldn’t get the corpsman, but I knew he was like 100 yards from me. I patched him up the best I could, hoping that in the morning I could get him [out] alive, because he was breathing. And I did all I could to hold him. And this corpsman got to me when it was still early [in the morning], and they pulled him down to the beach. I thought he made it.”

Abner and I served in wars that began 62 years apart, but we share this: You don’t say your friend’s full name if he made it out alive.

Getty Images

Marines in Kuwait prepare for war

‘I’m confident that this will be over soon.’

I met Brian Michael McPhillips at the end of our time at The Basic School in Quantico, Va. TBS is a six-month course that teaches Marine lieutenants the bare bones of leading an infantry platoon, even though most will go on to become specialists in other fields: aviation, artillery, logistics, supply, and so on. For our class of 240 students, there were three openings for tank officers. McP and I got two of them.

He was forthright and exacting, a New Englander with dark hair and icy blue eyes that hid nothing. He could bludgeon you with honesty or sarcasm, and like many Massachusetts natives, he had just enough charm to mitigate his asshole streak.

In the winter of 2001, we reported to Fort Knox together and joined a class of Army lieutenants, most of whom were reservists or National Guardsmen. Brian made no effort to hide his disgust for what he deemed their lack of knowledge, professionalism, and physical fitness. I tended to agree, but I at least tried to be nice to our colleagues.

McP had no time for niceties. He cared about training for war and keeping his Marines alive in battle; making friends wasn’t on his to-do list. Besides, he had me.

We were assigned to tank battalions on opposite sides of the country but ended up in the same desert for war. McP arrived in Kuwait a couple of weeks after I did, and his unit camped several kilometers away from ours. Still, he hitched a ride over one day and sought me out, no easy feat in a camp of four thousand Marines. I was out training with my platoon when he came by, so I didn’t see him that day. I never saw him again.

The war was mostly boring, except when it was terrifying. I’ve started forgetting even the memorable parts; I only recently recalled killing two Iraqi fighters with a coaxial machine gun — their bodies flung into the air like they’d stepped on cartoon springs — when I revisited an old diary. But the map is imprinted in my brain; the names of the cities and towns shine like beacons through the fog, checkpoints that put the war in order: Basrah. Nasiriyah. Diwaniyah. Numaniyah. Aziziyah.

Aziziyah is about 40 miles southeast of Baghdad’s outskirts, on the banks of a bulbous C-curve of the sidewinding Tigris. I didn’t fight there, but Brian did. My guess is the ambush came from the palm grove; it’s where most ambushes originated that spring, because they offered cover and restricted the movement of tracked vehicles. He was on top of a Humvee leading the scout platoon, returning fire with a .50-cal machine gun when he was shot in the head. I’ve heard rumors that the last thing he said was “I FUCKING LOVE THIS SHIT!” I’ve believed it for so long that it may as well be true.

Baghdad fell a few days later. I learned about his death 10 days after that. When my friend Charlie told me the news, I was standing in a garbage dump outside Baghdad; we’d left the city because tanks presented an “aggressive posture” that ran counter to the new mission of nation-building. We were going home.

When I boarded the Navy ship that would bring me back to the States, I checked my email for the first time in five months. On Jan. 31, 2003, McP had sent a characteristically terse note.

Friends and Family,

We are leaving for Kuwait this evening. Thanks again for all the support. I’m confident that this will be over soon. God bless.

Brian

The subject line was one word: goodbye.

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images

‘At what point do we do something about it?’

On the internet, I have watched a war of words, waged mostly among people who haven't fought for their country. One side, pained by a protest occurring during the national anthem, will say that our troops fight for the flag. The other side, typically, will point out that servicemen and women swear an oath to defend not the flag, but the Constitution.

I grew up on Air Force bases, and wherever we lived, the theater played “The Star-Spangled Banner” before every movie. My father, a pilot who served 22 years, had a habit of haranguing teens and young airmen for wearing hats or talking during the anthem. It became a running bit for our family: We’d identify disrespectful culprits in the crowd and watch my father’s blood boil until he marched over to correct them.

Later, as a student in ROTC, I spent three years on the color guard, skipping tailgates to present the colors at windswept Big Ten football games, where my drunken classmates watched from the stands.

I still stand at attention for the anthem, from the first bars until the final note ends. I don’t think I can be any other way. Like a Catholic making the sign of the cross, I stand for the anthem. It’s a rite tied to my identity, ingrained by family and belief.

Photo by Thearon W. Henderson/Getty Images

When Colin Kaepernick first sat during the anthem — before he consulted with the former Green Beret Nate Boyer and began kneeling — I took offense. How could I not? Kaepernick rejected a ritual that was part of my identity as an American. But it was also his First Amendment right to protest peacefully. I swore an oath to defend the Constitution, not my feelings.

As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie advised in Americanah:

Hear what is being said. And remember that it’s not about you. American Blacks are not telling you that you are to blame. They are just telling you what it is. If you don’t understand, ask questions. [...] Sometimes people just want to feel heard. Here’s to possibilities of friendship and connection and understanding.

I had to say it to myself: It’s not about me. It’s not about the troops. It’s about Kaepernick’s experience as a black man in America. And he started the protest because he saw black men dying preventable deaths. “I remember thinking our posture was like a flag flown at half-mast to mark a tragedy,” wrote teammate Eric Reid in The New York Times.

If you read or listen to what black Americans have to say about police violence, chances are good that at some point you will see the names of the dead repeated. Philando Castile. Michael Brown. Tamir Rice. Terence Crutcher. Freddie Gray. “I couldn’t see another ‘hashtag Sandra Bland,’ ‘hashtag Tamir Rice,’ ‘hashtag Walter Scott,’ ‘hashtag Eric Garner,’” Kaepernick said to reporters in 2016. “The list goes on and on and on. At what point do we do something about it?”

Saying their names is the vigil the living keep.

I’ve only recently realized that veterans do the same thing. More than 70 years after his best friends died on Iwo Jima, Greenberg still says their names whenever he can: Barney Aloysius Cochrane. George Andrew Schultz.

And Brian McPhillips. He’s as dead as Barney and George, as dead as Tamir and Terence. The circumstances of their deaths were different, but details matter little to the dead. Their lives ended in their youth, and they stay that age while the survivors grow middle-aged and old, the memories fading but not the names of the dead they loved.

Saying their names is the vigil the living keep, a flame tended so the light they brought to the world isn’t extinguished entirely.

“Life is ... it’s people,” Abner tells me. “It’s touching people.” It’s the end of our conversation, and we’ve been talking about war and the anthem and Black Lives Matter.

“We’re doing it to us. What they’re doing to our people — how do we allow it?” I’m not sure who he means by they. The aphasia that robs him of specificity makes it unclear if he’s talking about his war or my war or police violence. Maybe it’s everything.

“I recognized, I’m a culprit. Which I didn’t recognize before. ‘We gotta win this war. The Nazis are there, we gotta win this war.’ But it became beyond that.

“It wasn’t winning this war — it’s never having any wars.”

0 notes