#t.l.o

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Kronos but their Cyn.

T.L.O! Bad Ending where when The Gods burst into Olympus’s Throne Room, their met with the sight of Pęrcy hunched over the body of Luke, and think the day is saved,,, failing to notice the other bodies sprawled a bit away on either side of him…

“ Haha. Oh yes, , , get Snuck Upon :). ” — Křoñöş after possessing his grandson's body, erasing Luke from existence and ripping out his Divine granddaughter’s (Athena’s) throat :)c

#greek mythology#greek gods#bullshit to keep me going ♾️✨#slight shitpost#Pjo#percy jackson fandom#percy jackon and the olympians#percy jackson#pjo kronos#Pjo athena#luke castellan#riordanverse#Possession#Slight eldritch horror#F in the chat for Poseidon who had to watch the body of his son contort and move around like his bones r constantly snapping all while his-#Face has a extremely unsettling grin stretched on it :D#greek titans#Possession horror#Bad ending#Uncanny deities#Their fucked. That’s it.#Kronos but their Cyn A.U

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the case and address the following: Identify three justifications for the search Identify the special need and the expectation of privacy balanced in this case Present your own decision on this case.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the case and address the following: Identify three justifications for the search Identify the special need and the expectation of privacy balanced in this case Present your own decision on this case.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the case and address the following: Identify three justifications for the search Identify the special need and the expectation of privacy balanced in this case Present your own decision on this case.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the case and address the following: Identify three justifications for the search Identify the special need and the expectation of privacy balanced in this case Present your own decision on this case.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the case and address the following: Identify three justifications for the search Identify the special need and the expectation of privacy balanced in this case Present your own decision on this case.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the case and address the following: Identify three justifications for the search Identify the special need and the expectation of privacy balanced in this case Present your own decision on this case.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

I���n regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the case and address the following: Identify three justifications for the search Identify the special need and the expectation of privacy balanced in this case Present your own decision on this case.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the c

In regards to the case of New Jersey v. T.L.O, analyze the case and address the following: Identify three justifications for the search Identify the special need and the expectation of privacy balanced in this case Present your own decision on this case.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

New Jersey v. T.L.O., 1985

The Right to Search Students

By Fidel Andrada

★★★★★★★ Background of the Case ★★★★★★

A New Jersey high school teacher discovered a 14-year-old freshman, whom the courts later referred to by her initials, T.L.O., smoking in a school lavatory. Since smoking was a violation of school rules, T.L.O. was taken to the assistant vice-principal’s office.

When questioned by the assistant vice-principal, T.L.O. denied that she had been smoking. The assistant vice-principal then searched her purse. There he found a pack of cigarettes along with rolling papers commonly used for smoking marijuana. He then searched the purse more thoroughly and found marijuana, a pipe, plastic bags, a large amount of money, an index card listing students who owed T.L.O. money, and “two letters that implicated T.L.O. in marijuana dealing.”

The assistant vice-principal notified the girl’s mother and turned the evidence of drug dealing over to the police. T.L.O. was charged, as a juvenile, with criminal activity. T.L.O., in turn, claimed the evidence of drug dealing found in her purse could not be used in court as evidence because it had been obtained through an illegal search and seizure. T.L.O.’s attorneys claimed that the Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable search and seizure. They maintained that the Fourth Amendment requirements for a warrant and probable cause applied to T.L.O. while in high school as a student. After appeals in lower courts, the case eventually reached the United States Supreme Court.

Want to Know More? Click on this Link for the Outcome

https://5f6a28f65b7a5.site123.me/

0 notes

Photo

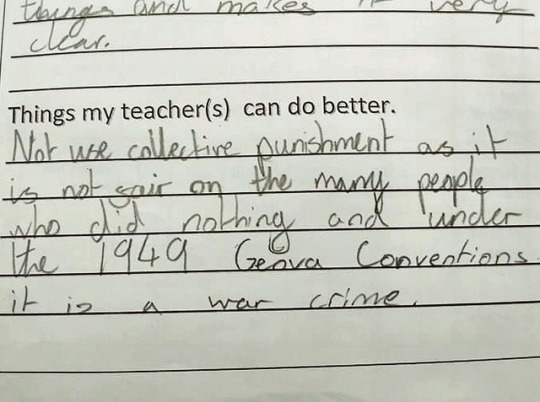

This is great and a power move on her part that the teacher can\ block by saying that within school her rights are limited according to Ingraham v. Wright(Although this had to do with corporal punishment in school whch is allowed to an extent) and New Jersey v. T.L.O , and honestly speaking , the school has the right to act in loco parentis which is basically taking care of you as parents would group punishments and all.

“Not use collective punishment as it is not fair on the many people who did nothing and under the 1949 Geneva Conventions it is a war crime.”

466K notes

·

View notes

Text

EXCLUSIONS OF THE EXCLUSIONARY RULE

By: Arzoo S. Kapil, Rutgers University - New Brunswick Class of 2022

March 23, 2019

Exceptions to the Fourth Amendment requirement of a warrant include (but, as always, are not limited to) consent, search incident to lawful arrest, plain view, stop and frisk, automobile, exigent circumstances including hot pursuit, community caretaker function, impounded vehicles, probation and parole searches, school searches, open fields, the independent source doctrine, good faith, inevitable discovery, the attenuation rule, and border searches.

Consent is arguably the clearest and simplest exception. Consent requires the person being searched to agree to the search; therefore, waving any need of a warrant. Once an individual consents to a search, he/she cannot argue that a warrant is necessary or that his/her rights are abridged as they waived any rights/protections when he/she agreed to the search.

Search incident to lawful arrest aims to protects police officers when a person is lawfully arrested. It also ensures that no evidence on the individual is tampered with or destroyed. Search incident to lawful arrest only permits the searching of the person and the area near him/her. It does not extend any further than that. To conduct other searches, a warrant would be required.

Plain view exception simply means that if evidence is viewable from where one is, then no warrant is required to seize it. This can extend to situations where a warrant is issued for the search of one thing, but another item is found. For example, if a warrant is for cocaine and the police also stumble upon weed, the weed would also be permissible. This, however, does not justify illegal entrances.

Stop and frisk, although heavily debated, is an exception as well. This exception allows for the searching individuals as long as there is a reasonable and articulate suspicion of the individual. This standard is less than that of probable cause. Also, if the police believe a person is dangerous and armed, they may also frisk him/her. This exception aims to protect the community.

Automobile exceptions stem from the idea that an individual can be out of reach of an officer due to the mobility a vehicle offers; so, there is not enough time to obtain a warrant. This exception requires for the probable cause standard to be met and includes but is not limited to automobiles.

Exigent circumstance applies a similar argument to the automobile exception. In this case, the urgency to search to prevent the destruction or removal of evidence trumps the need for a warrant. There is no defined circumstance for this as it is a very case-by-case situation.

Community caretaker function refers to the ability of police to search property that individuals in society turn in to them and property that is abandoned. This is simply to serve the community and protect it, as the name suggests.

Impounded vehicles are allowed to be searched without a warrant as it is considered standard police procedure to inventory and secure the vehicles.

People on probation, parole, or other forms of supervised release can be subjected to warrantless administrative searches under the "reasonable grounds" standard to ensure that the community is not harmed. In Griffin v. Wisconsin, Justice Scalia stated that "a probable-cause requirement would [reduce] the deterrent effect of the supervisory arrangement."

Regarding school searches, New Jersey v. T.L.O. found that a student's expectation of privacy must be balanced with the "substantial interest of teachers and administrators in maintaining discipline in the classroom and on school grounds."

Open fields have a lower expectation of privacy, diminishing the need for a warrant as the location is not private.

The Independent Source Doctrine states that evidence that was legally found should still be permissible in a case even if it were originally illegally found as there is nothing incorrect with the legal search.

The good faith exception protects officers from being prosecuted for an illegal search if the officers had reasonable, good faith belief that they were acting according to legal authority. Cases of this can be when the warrant is defective or even simply has a typo on it since that is not the fault of the officers.

The Inevitable Discovery Doctrine allows for evidence that was obtained illegally to be permitted if it would have been found in a lawful investigation. Some courts require the prosecution to demonstrate how the investigation would occur.

The Attenuation Doctrine allows for the inclusion of evidence found illegally if the connection between the misconduct and other evidence or confession is attenuated.

Border searches do not require a warrant, probable cause or suspicion of any kind simply to their nature to ensure the safety of citizens within the country.

________________________________________________________________

Arzoo S. Kapil is currently a Pre-Law student studying Business Analytics and Information Technology (BAIT) and Political Science at Rutgers University-New Brunswick. She is very interested in corporate and civil law and hopes to explore them in depth.

________________________________________________________________

0 notes

Text

Rebuttal: As Adults, Students Should be Able to Smoke as They Please - Albany Student Press

Albany Student Press

Rebuttal: As Adults, Students Should be Able to Smoke as They Please Albany Student Press In the 1985 Supreme Court case New Jersey v. T.L.O., two teenage students were caught smoking in their high school bathroom by a teacher and were brought to the principal's office. Once there, the principal forcibly took the girl's handbag and searched ...

from smoking pipe - Google News http://ift.tt/2FNvsPY via http://ift.tt/2wx2G1p

0 notes

Text

Can I travel to South Korean this June?

— 미찬⁷ (@af_min95) Thu Apr 02 08:31:26 +0000 2020

Yeah

— T.L.O. Ty🐉 (@glitty_) Thu Apr 02 08:49:55 +0000 2020

0 notes

Text

Proms and PBTs

Spring is only a few weeks away. Soon preparation will begin for the rites of the season, among them pruning, planting, and, of course, prom.

A few weeks ago, I chaperoned a dance at my son’s high school. (I elected not to tell him that I was chaperoning, so you can imagine his reaction when he saw me there. For more about that, please check out my parenting blog.) When I walked into the gymnasium, I saw tables laden with dozens of bright yellow flashlight-shaped devices. The school had not stockpiled flashlights for gazing into dark corners. Instead, these were portable breath testing instruments awaiting samples of air drawn from the deep lungs of teenagers. Every student seeking admission to the dance was required to submit a breath sample. Only students who registered no alcohol concentration were eligible to attend the dance.

After the dance, someone asked me whether it was lawful for a school to require students to submit to a breath test before admitting them to a school function. My answer? Yes. My reasoning? See below.

Breath tests are a Fourth Amendment search. The question was a reasonable one given that when a government official carries out a breath test, he or she conducts a Fourth Amendment search. See Skinner v. Railway Labor Executives’ Ass’n, 489 U.S. 602, 617 (1989) (holding that “a breathalyzer test, which generally requires the production of alveolar or ‘deep lung’ breath for chemical analysis” is a search governed by the Fourth Amendment); People v. Chowdhury, 775 N.W.2d 845, 854 (Mich. App. 2009) (rejecting argument that because a portable breath test is less intrusive than a Breathalyzer test, it is not a search for purposes of the Fourth Amendment); cf. State v. Jones, 106 P.3d 1, 6 (Kan. 2005) (asserting that while “[i]t would be overbroad to declare that all PBT[]s are searches [given that some use passive sensor technology to detect the presence of alcohol in an area where a person is breathing normally] . . . the particular PBT used on [the defendant] tested his deep lung breath for chemical analysis and, under Skinner, was a search subject to the strictures of the Fourth Amendment”). For such a search to satisfy the reasonableness requirement of the Fourth Amendment, it generally must — absent the person’s consent to the search, exigent circumstances, or a special needs exception — be carried out pursuant to a judicial warrant issued upon probable cause.

Searches by public school officials are special needs searches. Searches by public school officials are among the types of searches that fall within the special needs exception to the general requirement of a warrant and probable cause. See Vernonia School District 47J v. Acton, 515 U.S. 646 (1995) (so stating); see also Griffin v. Wisconsin, 483 U.S. 868, 873 (1987) (noting that the Supreme Court has permitted exceptions to these requirements when “special needs, beyond the normal need for law enforcement, make the warrant and probable-cause requirement impracticable”). The Supreme Court has reasoned that, in the public school context, the warrant requirement “would unduly interfere with the maintenance of the swift and informal disciplinary procedures.” New Jersey v. T.L.O., 469 U.S. 325, 340, 341 (1985). Moreover, “strict adherence to the requirement that searches be based upon probable cause” would undercut “the substantial need of teachers and administrators for freedom to maintain order in the schools.” Id. The legality of such a search depends instead on its reasonableness under all the circumstances.

Indeed, the high court in Acton dispensed with the requirement of individualized suspicion altogether, upholding as constitutional the random, suspicionless drug testing of student-athletes by public schools. 515 U.S. at 664-65. In reaching its conclusion, the Court relied upon (1) students’ decreased expectation of privacy with regard to medical exams and procedures required by and performed at school and athletes’ further decreased expectation of privacy given locker room conditions, (2) the fact that urine samples were collected in relatively unobtrusive circumstances approximating those regularly encountered in public restrooms, and (3) the severity of the need to ensure that role-model student athletes did not use drugs and thereby fuel the school drug problem. The Supreme Court expanded Acton’s reach in Board of Education of Independent School District No. 92 of Pottawatomie County v. Earls, 536 U.S. 822 (2002), upholding a school policy requiring middle and high school students to consent to suspicionless drug testing in order to participate in any extracurricular activity. The Earls Court minimized the distinction between athletic and other extracurricular activities, reasoning that students participating in extracurricular activities also had limited expectations of privacy and that the drug testing program was a reasonably effective means of addressing the school district’s legitimate desire to prevent and deter drug use among schoolchildren.

Lower courts have relied upon Acton in upholding other types of suspicionless searches of students. See In re Latasha W., 70 Cal.Rptr.2d 886 (Cal. Ct. App. 1998) (upholding as lawful the search by hand-held metal detector of a student selected at random; after detector beeped, student was asked to open her pocket, revealing a knife); State v. J.A., 679 So.2d 316 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1996) (upholding lawfulness of search carried out pursuant to school policy authorizing random searches of students in high school classrooms with hand-held metal detector wands; a gun was discovered in the student’s coat); People v. Pruitt, 662 N.E.2d 540 (Ill. App. Ct. 1996) (upholding as lawful the pat-down search of a student by a school-liaison police officer after a metal detector that the student was required to walk through to enter the school reacted; a gun was discovered in the student’s pants pocket). And while special needs searches must be divorced from the State’s general interest in law enforcement, the subsequent criminal prosecution of a student based on evidence discovered in a special needs search by school officials apparently does not a fortiori render the search unlawful, see, e.g., Pruitt, 662 N.E.2d at 547, though the sharing of information with law enforcement is a factor in evaluating the objective for and lawfulness of the search, see Board of Education of Independent School District No. 92 of Pottawatomie County v. Earls, 536 U.S. 822, 833 (2002) (noting that results of drug tests of students who wished to engage in extracurricular activities were not turned over to any law enforcement authority); cf. Ferguson v. City of Charleston, 532 U.S. 67, 82–84 (2001) (holding that a state hospital policy requiring the diagnostic testing of pregnant women meeting certain criteria, such as history of drug abuse, could not be justified by the special needs exception because the results of the warrantless blood tests were frequently handed over to law enforcement; stating that “[w]hile the ultimate goal of the program may well have been to get the women in question into substance abuse treatment and off of drugs, the immediate objective of the searches was to generate evidence for law enforcement purposes in order to reach that goal.”)

Application to portable breath tests administered before a school function. Public schools have an interest in ensuring that students do not consume alcohol in connection with school functions. Consumption of alcohol by underage persons is associated with driving while impaired and other dangerous behaviors by young people. And students who have consumed alcohol may act disruptively at school functions. Given a school’s tutelary authority over students, it is reasonable for the school to adopt measures to discourage students from attending school functions after consuming alcohol. Requiring all students to submit to a minimally intrusive test that reveals nothing more than whether they have recently consumed alcohol is a reasonable manner of accomplishing that objective.

Plus, the students consent. In some of the circumstances mentioned above, students were searched in connection with their presence at a school that they were required by law to attend. Attending an after-school function like a prom is different from compulsory school attendance. Thus, submitting to a breath test in this circumstance also may be deemed reasonable on the basis of students’ consent to search.

How did the dance turn out? I don’t believe any students were turned away from the dance I attended based on a positive breath test. I’ve heard anecdotally that no student ever tests positive. The students know before coming that their breath will be tested. I’m sure the tests don’t prevent students from drinking altogether. But the administration of portable breath tests do appear to be an effective and lawful way of deterring students from drinking before attending school functions.

The post Proms and PBTs appeared first on North Carolina Criminal Law.

Proms and PBTs published first on https://immigrationlawyerto.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Academic Sample

Shedding Privacy Rights at the Schoolhouse Gates

Deterring drug use among youth has been a campaign among local, state and federal governments since drug abuse became a nationwide problem in the 1960s and ‘70s. One of the measures that schools began to adopt in order to prevent drug use in the 1990s was drug testing students. The constitutionality of drug testing was challenged by students seeking to protect their privacy interests until it eventually reached the Supreme Court. Ultimately, they would have to decide if the government had a compelling interest in deterring drug use amongst its students and if this was narrowly tailored in order to achieve that interest. Although the court in Board of Education v. Earls approached the issue of drug testing students within the legal framework by adhering to precedent, the ruling ignited political controversy around the country.

Procedures requiring suspicionless drug testing in schools were created in response to the increasing drug problem among youth in the decades preceding litigation on the matter. According to a Gallup poll, 66% of Americans considered marijuana to be a serious problem in the middle and high schools within their area in 1978; 35% said the same when referencing hard drugs (“Decades of Drug Use”). In 1983, the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) program was instituted in schools. Within the program, uniform police officers would go into schools to warn students about the dangers of drugs and to promote drug-free lives. This program brought the conversation on drug abuse into schools once a week, for approximately 60 minutes (“Why ‘Just say no’ Doesn’t Work”). However, since its implementation, there has been little evidence generated regarding its effectiveness. In fact, a recent study demonstrated that D.A.R.E. had almost no effect on a teen’s peer resistance skills (Ennett). Throughout the 1970s, drug use amongst teens continued to rise.

By the time the mid-80s rolled around, crack cocaine had transformed youth drug use, particularly within inner cities. Crack lured users with its cheap, addictive qualities and it was plentiful in nature. The introduction of crack prompted President Reagan to sign the “National Crusade for a Drug-Free America” anti-drug abuse bill into law on October 27, 1986 (“ReaganFoundation.Org”). Two years later, Nancy Reagan spearheaded a “Just Say No” campaign, creating clubs across the country and throughout the world in an attempt to decrease youth drug use. According to the Reagan Foundation, high-school senior cocaine use reportedly dropped by 1/3rd following this campaign (“Ronald Reagan”). Following this, Congress passed the Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act of 1994. This provided federal grants to educational institutions for drug and violence prevention programs that are “designed ‘to combat illegal alcohol, tobacco and drug use” ("Board of Education v. Earls - Amicus (Merits)"). This is the source of federal funding for drug tests in schools demonstrating how the federal government provided incentives to the schools in order to fulfill their national drug policy agendas. The data on teen drug use in the 1990s is mixed. However, according to a Gallup poll, admitted teen marijuana use plunged from 38% in 1981 to 20% in 1999 ("The '80s and '90s").

The courts became involved in the mid-1980s when school authorities began performing “suspicionless searches” in response to rising teen drug use. The Supreme Court ruled in New Jersey v. T.L.O. (1985) that school officials may search a student’s property if they have an individualized “reasonable suspicion” that a school rule has been broken. Therefore, they do not need probable cause in performing the search. This means a warrant is not necessary to establish the reasonableness of all government searches. This ruling drew the line between a student’s legitimate expectation of privacy and a school’s legitimate expectations for maintaining order (Mersky).

Later cases upheld the constitutionality of drug tests as searches within schools. In Skinner v. Railway Labor Executives’ Association (1989), the court found that state-compelled collection of urine constitutes a “search” subject to the Fourth Amendment. The court, in this case, sided with the government stating that employers can subject their employees to drug tests if they are involved in an accident while on the clock (“Skinner v. Railway”). This ruling set the tone for drug-testing students to be considered a “search” under the Fourth Amendment. Furthermore, in Todd v. Rush County Schools (1989), the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the constitutionality of random drug-testing as a condition for participation in other extracurricular activities. With the Supreme Court refusing to hear the case, the verdict of the court of appeals stood (“Student Drug Testing”). Combined, these cases would be used as justification for suspicionless based drug testing for extracurricular activities in schools.

Perhaps the most influential Supreme Court decision leading up to Board of Education v. Earls occurred in 1995. Vernonia School District 47J v. Acton arose when James Acton, a seventh grader in the school district, signed up to play football. When he signed up, he was presented with a consent form that required all student-athletes to be drug tested. When he and his parents refused to sign the consent form, he was denied participation. Acton challenged the district’s policy all the way up to the Supreme Court. Justice Scalia issued the opinion. The opinion traced the origin of the drug problem back to the 1980s where “teachers and administrators observed a sharp increase in drugs” ("Vernonia Sch. Dist. 47J”).

Initially, the school district turned to education as a solution. They held special classes, speakers and presentations all in an effort to deter drug use. However, the drug problem persisted. After hosting open forums, the district implemented a student-athlete drug testing policy. The District felt that “athletes were leaders of the drug culture”. The athletes were to be tested at the beginning of the season, and randomly throughout. The District argued that student-athletes have minimal legitimate expectations to privacy within the sport. Playing a sport requires them to “suit up” before each practice or game and then shower and change afterward. In school showers, student-athletes already have minimal expectations of privacy. Therefore, the court justified and upheld the District’s policy finding that “the effects of a drug-infested school are visited not just upon the users, but upon the entire student body and faculty” ("Vernonia Sch. Dist. 47J”). It is the Vernonia decision that upholds the constitutionality of random drug testing of student athletes because the school has a compelling interest in preventing teenage drug use, placing prevention above privacy.

The facts of Board of Education v. Earls are much like those in Vernonia, except they diverged on the students being drug tested. The Student Activities Drug Testing Policy was adopted by the Tecumseh, Oklahoma School District in the Fall of 1998. The policy required students in the middle and high schools to consent to drug testing as a requirement to participate in any extracurricular activities, not just student-athletes. The student would be required to submit to random drug testing before participating, during and “must agree to be tested at any time upon reasonable suspicion” ("Board of Education v Earls"). In protest, two Tecumseh High School students challenged the testing and brought suit, arguing that the policy violated the Fourth Amendment. Initially, the District Court granted the School District summary judgment. The Court of Appeals reversed and held that the policy did, in fact, violate the Fourth Amendment. The court concluded that the school’s compelling interest would have to rely on it demonstrating an “identifiable drug abuse problem among a sufficient number of those tested”, which the school failed to demonstrate ("Board of Education v Earls”).

When the case reached the Supreme Court, Amicus curiae briefs filed in for both sides, with briefs similar to those in Vernonia. On behalf of the petitioners was Deputy Solicitor General Paul Clement on behalf of the United States, a soon-to-be George W. Bush appointee to Solicitor General. Just as the United States had done in Vernonia, Paul Clement argued that drug use was not only a threat to school children but a threat to “the health of the Nation itself” ("Board of Education v. Earls - Amicus (Merits)"). As a whole, the United States believes their general role is to protect children and families from the dangerous effects of drugs. Also filing an amicus curiae for the school district, just as they had done in Vernonia, was Washington Legal Foundation, a conservative public law group. The foundation was backed by U.S. Senators Don Nickles and James Inhofe, both Republican senators from Oklahoma. They were joined by Oklahoma Governor Frank Keating, a Republican nominee, and Wes Watkins, a newly-transitioned Republican U.S. Representative. The Foundation did not believe the school should be required to wait for evidence of drug abuse in Tecumseh to institute strong policies to prevent it. Overall, they discussed the tragic consequences of drug use and urged the court to find for the district (“The Oxford Companion”).

In support of the respondents came forth an amicus curiae brief headed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, National Education Association and National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, among others. The rather lengthy brief summarized key points in the respondent's’ arguments. First, the brief asserted that the policy is unreasonable because students in extracurricular activities are far less likely to use alcohol, tobacco or other drugs in comparison to their peers. Sandra Day O’Connor referred to this particular point of the brief during oral arguments. Secondly, they argued that the testing is an unreasonable invasion of student privacy that should not be tolerated. In fact, the “urine collection is itself a significant intrusion”. This invasion of privacy, the brief continued, will likely deter students from participating. The brief concluded by stating that the policy instituted has not proven to deter drug use and the drug-use detection is not a part public schools’ core responsibilities (“Supreme Court”). The briefs presented reflect the controversy of drug testing for extracurricular activities in public schools.

Following the filing of the briefs came oral arguments beginning on March 19, 2002. Oral arguments began with the county, represented by one-shotter attorney Linda M. Meoli. The county’s main objective was to prove that the policy in Tecumseh was relatively the same as that upheld in Vernonia. However, Ruth Bader Ginsburg feared the policy engaged in a slippery slope. She argued that this expanded policy would essentially allow schools to drug test students who merely want to take an elective. Additionally, John Paul Stevens was interested in knowing if any sanctions were imposed on the student if he or she fails the test, other than not being able to compete. Meoli quickly answered no, and assured that the purpose of the policy is not to punish students (“Board of Education of Independent”).

The oral arguments then turned to Graham A. Boyd as the attorney for Earls. Boyd is known nationwide for his political efforts to reform drug laws, which is why he was selected to represent the students (“Statement of Graham”). His main argument was that the court should use the individualized reasonable suspicion standard set forth in TLO and not the standard set forth in Vernonia. Justice Kennedy, also worried about the slippery slope, inquired if Boyd would be challenging police dogs and locker searches in schools next. Boyd rejected this argument and contended that he would not do so unless they involved blanket intrusive searches. The question then was brought back to whether or not there was a proven drug problem in schools nationwide. Boyd responded that there may be a nationwide issue, but that the problem has been greatly exaggerated in the amicus briefs filed by the petitioner and by opposing counsel. On that note, the arguments drew to a close.

Three months later on June 27, 2002 the court had reached its decision. The majority opinion is authored by Justice Thomas joined by Rehnquist, Scalia and Kennedy with Breyer filing a concurring opinion. It is worth noting that it was particularly rare that Justice Thomas wrote the opinion, and, furthermore, that he obtained a majority. However, as such, the majority relied their entire ruling on the precedent established in Vernonia, which seems to be the best avenue they could have taken. First, Thomas evaluated the policy’s reasonableness and utilized the balancing test established in Vernonia. Essentially the court would balance the individual’s right to privacy and the promotion of legitimate governmental interests. The legitimate governmental interests promoted here would be the public school’s role having “a custodial and tutelary responsibility for children” ("Board of Education v Earls"). When weighing the competing interest of individual privacy, the majority found that expectations of privacy in a school setting are limited. Further, the majority found that the testing for drugs is not overly invasive. The state’s role as a custodian requires them to maintain “discipline, health and safety”. This is why school children are required to undergo physical examinations and vaccinations against disease. After applying the test from Vernonia to the facts of this case, the majority found that the compelling government interest outweighed any right to privacy a student may have. Lastly, they asserted that the Court does not require evidence of a drug problem before the government can conduct suspicionless drug testing ("Board of Education v Earls").

In Justice Ginsburg’s fiery dissent, she applies the same balancing test the majority did from Vernonia. The question is whether it is reasonable for the school to conduct drug testing. The remedy is to balance the governmental interests against individuals’ right to privacy. Justice Ginsburg compares the drug problem faced in Vernonia to that in Tecumseh. In Vernonia, the school reported to the federal government that the students involved in interscholastic athletics were “fueled by alcohol and drug abuse”. Furthermore, athletes were singled out to be tested because they were found to be “leaders of the drug culture”. In the years leading up to the policy instituted in Tecumseh, the school reported to the federal government that drugs were not a “major problem” within their schools ("Board of Education v Earls"). This makes the governmental interests even less compelling. In this sense, Justice Ginsburg is arguing that a better approach would be to judge district-by-district. A potential conflict neither the majority nor the dissent commented on was the constitutionality of drug testing all students, regardless of their participation in extracurricular activities, which would rise later on through lower courts. The dissent concludes by applying the balancing test from Vernonia and finding that the legitimate expectations to privacy outweighed the interests presented by the school district.

The heavy reliance on both the majority and the dissent to rely on precedent illustrates that they were approaching the case from a legal perspective. In relying on Vernonia, they sought only to reach decisions within the legal framework and essentially to make good law. On the other side, one could argue that the justices voted ideologically on this matter instead of legally. If one breaks down the justices ideologies compared to their votes they will see that the argument is flawed. The two Democratic appointees on the Rehnquist court at this time were Breyer and Ginsburg. Justice Breyer, although he has a “moderate liberal image” joined the conservatives in the majority (Hensley). The same theory goes for Justice Stevens. Although a “moderate Republican”, he has voted liberally “71 percent of the time”. He joined Justice Ginsburg in the dissent. In this case, Justice Stevens has proven to go against his ideologies in seeking to make good law. Justice O’Connor, a Reagan appointee, additionally joined the dissent with Justice Ginsburg, thereby proving the decision did not rest on ideologies.

With the suspicionless based drug testing of students upheld in Earls, one may wonder the exact impact this has had nationwide on schools. There is research that indicates “currently less than 5% of high schools in the U.S. perform random drug tests on their students” (“Student Drug Testing”). Another study by the Journal of Adolescent Health combats these claims and states that the percentage may be slightly greater. They began studying the impact of Earls by surveying 745 schools nationwide. From 1998-2001, they concluded that 2% of middle school students were subjected to random drug testing. From 2005-2011, this increased to 9% and remained constant. For high school students, 6% were subjected to random drug testing in 1998-2001. This number increased to 11% in 2005 to 2007 and to 14% in 2008-2011 (Ennett). However, one might expect with the prominence of the Earls ruling why these numbers don’t show greater statistical significance. A second survey at Northwestern University explains the reasons why some schools don’t implement drug testing of their students.

The Northwestern University research began by surveying ten schools in one Midwestern county. The survey found that out of the ten schools surveyed, three utilized drug testing. One school began drug testing in 2002 for students who have previous drug violations. The other two began drug testing their student-athletes in 1997, therefore not a result of Earls but more likely of Vernonia. The research they conducted showed that if a principal morally opposed drug testing the students, there would be no such policy implemented. This goes to show how the nature of the ruling on purely legal criteria affected political beliefs on the issue following. With the politics on whether or not principals morally oppose drug testing, there is great discretion in school leadership over whether or not to implement the program. The schools that did not implement drug testing of students stated that there are a variety of barriers to effective implementation. The first is that it is difficult to get support from all members of the community (including students). The second barrier they stated was cost. Another reason it is hard to implement is there are great problems preserving confidentiality and maintaining student trust (Conlon). The study also found that the principals felt there are more useful ways of deterring drug use in their schools. These include random locker searches, random searches by drug-sniffing dogs, systems of rewards for avoiding drugs, referrals to student assistance programs and assemblies or other educational efforts (Conlon).

One reason principals stated they do not drug test their students is because the process is costly. Therefore, even if the ruling had an impact on the politics of drug testing students, there are barriers to its implementation that make the court’s decision almost irrelevant. If the school chooses to conduct the testing themselves and tests approximately half its students (with 1,000 students in the school), the estimated cost is $6,800 per year. The kits themselves are about $10.00 each. If a student tests positive, there will need to be confirmatory tests. Confirming the tests costs $90 each. These procedures incur outside costs as well, such as paying the school staff time to learn about the program, the costs of collecting the samples and doing the tests and of handling students who test positive, along with preserving the students’ privacy. If the school chooses to utilize a third party administrator for the program, they charge about $25.00 per kit. If the school has 1,000 students and 50% of them are randomly tested, the costs can get up to $12,500 per year (“How Much Does”).

With all of these costs to the program, one of the deterring factors may be that it is hard to secure funding. There are a variety of ways schools that do implement the program secure funding. One way is to make the program a routine item to the school’s annual budget. Another is to get federal grant money from the U.S. Department of Education Safe and Drug-Free Schools as part of the school’s Title I funds. Other avenues schools may approach are fundraising from individuals or businesses within the community (“How Much Does”). However, these measures are timely for the staff involved.

Another reason schools may not be implementing suspicionless based drug testing of its students is because the drug problem is decreasing nationwide. According to a study at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, there has been a gradual decline among eighth, tenth and twelfth graders across the country reporting use of illicit drugs. Their studies show that youth drug use peaked in the mid-1990s and since then has fallen. The number of 8th graders reporting the use of an illicit drug in the past 12 months before the survey was 24% in 1996 but fell to 13% in 2007. This drop of nearly half illustrates that schools may not be implementing suspicionless based drug testing because the drug problem has significantly decreased. Tenth graders use dropped from 39% to 28% in the same time period, still a statistical change worth mentioning (“Overall, Illicit Drug”).

Many of the conversations surrounding drug testing of students following the ruling of Earls have been to discuss the ineffectiveness and costly measures of drug tests. Some policies in schools nationwide have expanded to include random drug testing all students, regardless of their participation in extracurricular activities. In this way, the ruling has effectively altered discussion on the topic where schools seek to go beyond the ruling. However, given the discretion of the school board and principals on whether or not to implement the policy locally, there seems to be a great deal of politics still surrounding the issue of drug testing students. It seems as if the ruling did not solve all of the issues at stake here, and it will likely take another Supreme Court decision to justify the constitutionality of schools randomly drug testing students across the board for simply being students at the school.

The political discussions on the constitutionality of drug testing students are likely to continue the more schools nationwide implement them. Schools have utilized Earls to go further and expand their drug testing procedures to combat illicit drug use. Although the drug problem nationwide has been proven to be decreasing, this has not stopped schools in implementing programs to deter drug use. The Earls decision revitalized the conversation on drugs and student privacy rights and brought all members of the community in on the discussion. The legal approach taken in Board of Education v. Earls brought forth new de facto concerns that altered the political debate on drug testing students.

0 notes