#systems which were targeting queers at the time HEAVILY and continue to do so

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

two articles on psychiatric medication

I'm planning on writing a bigger psychiatry-critical piece soon about how the overwhelming majority of both leftists and trans people that I know believe themselves to be necessarily reliant on either psychiatric medication or therapy or both, and permit themselves (rather, semi-deliberately evacuate themselves of agency in identification with those harming them, I do not wish to victim blame) to be extensively abused by the psychological-psychiatric medical system in a fruitless search of validation for their malaise in some horrible cycle of iatrogenic dependence.

In particular, I know at least two transgender people personally (one male, one female) who are so heavily medicated that I have few compunctions about calling what is being done to them a kind of chemical lobotomy. They have both been left minimally functional and dramatically changed in personality by their "treatments", but both still seek out psychiatry to endorse their transgender interpretation of themselves, despite the fact their doctors are brutally and with little humanity "re-adjusting" them out of inconvenient behavior through repeated hospitalization, high and probably inappropriate doses of lithium alongside multiple other medications, and of course their whole gender treatment paradigm.

So I am continually startled by not only the distinct lack of modern leftist criticism of psychiatric medical institutions but outright collaboration with these institutions. Many people in the broader community-- whether radical queers or lesbian feminists-- purport to value self-reliance and peer support networks, distrusting well-funded and politically undermining officially-sanctioned institutions, but I am not sure I know a single gay person in my everyday life who is not regularly attending counseling sessions of some variety or another or who is not taking psychiatric medications-- prescribed by a psychiatrist that they see monthly or sooner-- that they believe they cannot live without.

One of the reasons I am so critical is that I was once one of these people: I have been on at least fourteen different psychiatric medications in various combinations throughout my life, and both I and many of my doctors believed that I was so critically ill that I could not live a meaningful or even minimally functional life without them. I, or my depression-- we were coextensive, inseparable, my personhood was inconvenient to assessment, I suppose-- was considered so deeply treatment resistant that I had multiple psychiatrists tell me to my face that it might not be possible to help me (of course, while still holding the prescription pad). I was lucky to never have been on lithium or Lamictal, nor subjected to electroshock, but all were floated as an unfortunate but potentially necessary part of my treatment plan. I was indeed considered such a hopeless case that I was actually approved for disability payments for mental illness, without appeal, an extreme rarity in the United States, especially at such a young age (23). I do not know for sure or not whether I could have set the grounds to get my shit together without the intervention of psychiatry-- I did survive long enough to leave an abusive home, after all-- but I do not consider it a coincidence that I did not get my shit together until I stopped having a therapist whispering in my ear and stopped having these substances in my body.

I don't think you can understand the modern transgender movement-- whether the push to identify various gender-distressed people as having a disorder or just niche lifestyle in need of medicalized affirmation, or the ideology that demands we believe that gender identity is an essential characteristic of human beings-- without understanding the history of psychiatry as a coercive practice attempting to normalize the socially abnormal, often in service to extremely oppressive interests, and the history of therapy as inherently individualizing and anti-political, an authority-laden substitute for discernment and appropriate and healthy social feedback.

In any case, I want to keep it short today, and it's with this context I want to share with you two articles, one from the New Yorker and the other from NPR.

The first article, by the amazing writer Rachel Aviv, who has previously covered dense and thorny ethical issues regarding psychiatric treatment and the construction of mental illness, is a critical article about how many modern psychiatric patients come to take consecutive strings of multiple psychiatric medications, coming to have and then losing faith in their doctors and medications to fix their ills. It follows a woman who decided to withdraw from her medications and the people she meets as she must build her own support network during her process of withdrawal, given her unhealthy dependence on the psychiatric network treating her and the psychiatric industry's public denial that medication discontinuation symptoms even occur, nonetheless can have severe and life-disrupting effects. Aviv gives a contextual history and science of the use of several classes of modern psychiatric medications, including their incredible limitations given psychiatry's practice and value system; in a description that will read eerily familiar to any detransitioned woman, she states that "there are almost no studies on how or when to go off psychiatric medications, a situation that has created what he [Allen Frances, chair of the DSM-4 committee] calls a 'national public-health experiment.'"

An important excerpt relevant to both general psychiatry and the practice of transgender medicine and health care:

A decade after the invention of antidepressants, randomized clinical studies emerged as the most trusted form of medical knowledge, supplanting the authority of individual case studies. By necessity, clinical studies cannot capture fluctuations in mood that may be meaningful to the patient but do not fit into the study’s categories. This methodology has led to a far more reliable body of evidence, but it also subtly changed our conception of mental health, which has become synonymous with the absence of symptoms, rather than with a return to a patient’s baseline of functioning, her mood or personality before and between episodes of illness. “Once you abandon the idea of the personal baseline, it becomes possible to think of emotional suffering as relapse—instead of something to be expected from an individual’s way of being in the world,” Deshauer told me. For adolescents who go on medications when they are still trying to define themselves, they may never know if they have a baseline, or what it is. “It’s not so much a question of Does the technology deliver?” Deshauer said. “It’s a question of What are we asking of it?”

The second article, which also contains a longer-form audio interview with the author, is about a new book by Harvard historian of science Anne Harrington called Mind Fixers: Psychiatry's Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness. What I found particularly striking about her interview is Harrington's assertions about the state of psychiatry and psychiatric pharmaceutical research now-- she claims that the psychiatric medication market has stalled because of research finding that many common antidepressant medications work no better than placebo versions, and that pharmaceutical companies therefore are de-investing from psychiatric medication research and development because they can no longer use their previous strategy of slightly tweaking the chemical components of previously monetizeable drugs. She states there have been very few innovations in finding new classes of antidepressant medications in particular (the most easily marketed psychiatric drugs, for whom the target population can easily be expanded).

I think her points here are crucial to understanding exactly why pharmaceutical companies and psychiatry have become increasingly invested in transgender health care and in expanding the market for hormones and transgender-related surgeries through promoting interventions like HRT and "top surgery" as elective procedures suggested as ways to "affirm a patient's identity" rather than "treat a disorder". The gender critical blogger Brie Jontry, a mother of a formerly trans-identified female teen, calls this practice and ideology "identity medicine", a term I find useful to describe the unholy conglomeration that is the individualized medicalization of gender-related distress and the advertising of medical treatments (particularly those provided by cosmetic surgeons) as ways to facilitate self-expression and authenticity. Given increasing attempts by gender doctors to create patients permanently dependent on exogenous hormones (those children left with non-functional gonads after treatment with GnRH agonists like Lupron and cross-sex hormones, or those transgender people who have had theirs removed) or to convince patients that gender dysphoria is a life-long, inescapable condition that they had already failed in not treating/affirming earlier (because you Always Were A Boy), I have to note parallels with psychiatric medicine's anti-recovery, anti-patient-autonomy assertions about other recently marketed drugs such as atypical antipsychotics, on which patients are also purportedly permanently dependent, or antidepressants (as above) where withdrawal symptoms purportedly prove that a patient is doomed to relapse should she cease psychiatric treatment. "Informed consent" and the formation of transgender resources outside a "gatekeeping" paradigm, where patients need not seek insurance approval nor the opinions of several doctors of different specialties for transgender medical interventions, nor wait a set period of time prior to transitioning, is often lauded as progressive and anti-institution by radical transgender activists, who can rightly see issue with a psychiatry put in charge of policing the intimate personal beliefs, coping mechanisms for misogyny or homophobia, and individual gender expression of its patients. However, I can't but see this as part of a new and terrifying medical strategy regarding transgenderism, where a loss of patient agency is replaced with the false sense of consumer choice; we have seen this in other realms of psychiatry, where forms of psychiatric incarceration were rebranded as the choice to take a break or "finally" seek help after self-negatingly denying it for so long, where tranquilizing drugs were rebranded as assistive devices for women struggling to have it all, and where high-risk, heavily sedating antipsychotic medications were rebranded as ways to give other psychiatric medications a "boost" should you still experience unhelpful emotions after complying with psychiatric treatment. "Gender dysphoria" is increasingly nebulous, something you might have had all along if you experienced various forms of generic malaise or failed to have your suffering sufficiently validated and thereby dissipated by psychiatry; funny that we've seen this before with other conditions and their treatments, and psychiatry somehow always comes up with a money-making solution for its own problems.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Studies of Devassos No Paraíso by João Silvério Trevisan - Part II

About the representation of queer people in the Brazilian modern mainstream media

I’m skipping a bit of the vast historic background in Devassos no Paraíso provides to focus on the chapters where Trevisan (2018) describes the appearance of queer personalities and other artists that broke with the heteronormativity from the 70s onwards. It is important to remember that during this period of time, Brazil was going through a military dictatorship that was going to last until 1985. In addition, in 1968 a series of laws named The Institutional Act Number 5 (AI-5) was put into action. The AI-5 determined that the president (non-democratically elected) could, without any jurisdictional review, shut down the Congress, discharge congressman, suspend the rights of any citizen for 10 years, suspend habeas-corpus, amongst others. This led to high persecution of anyone or anything considered to be “subversive”: countless arrests of artists and activists - some even exiled, reports of torture from government agents, and heavy censorship on media and entrainment.

Having this said, the chapters start by commenting on the emergence of young liberation movements, not necessarily associated with any political side, but dedicated to a self immersion. The first icon of this movement was the singer and composer Caetano Veloso. He constantly broke with heteronormative expectations of the time, wearing bras and lipstick on stage, kissing his band members and stating a clear identification with a feminine side. Even though Veloso never stated he was gay or bi, there were comments of his admiration of the same sex in some of his lyrics.

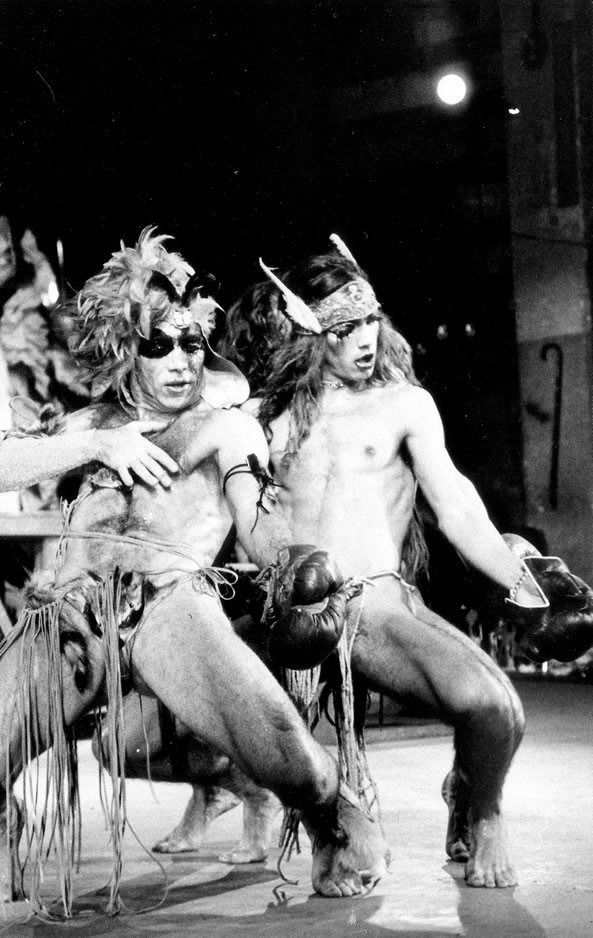

Another important mention was the theater group Dzi Croquettes. They were the ones to introduce the gender fuck movement: originated in San Francisco, it consisted of gay men who liked to wear feminine symbols but mixed it with strong masculine traits like beards and hairy chests. The group performed dances and told provocative jokes on stage, they were a fundamental piece in breaking the heteronormativity in the LGBTQ+ community.

Above: (1) two members of Dzi Croquettes performing on stage

Following the tendency of playing with gender symbols was Ney Matogrosso. He had great success amongst different age and social groups, representing a figure of mystery. Contrasting glitter, makeup, skirts, feathers, and a hairy chest, Ney was a phenomenon as the lead singer of Secos & Molhados and, later on, in his solo career. He suffered plenty of verbal and nonverbal aggression, even being kicked out of the stage at one point (Pereira, 1982), but nevertheless always was a clearly stated homosexual. The singer said once in an interview (1978) that his mission was to “end the tale that [being] homosexual was something sad, suffered, that you need to hide”. Mostly, Ney Matogrosso represented artistic freedom to break with gender stereotypes and symbols; apart from his clothes, he constantly mocked masculinity in his lyrics and performance. To Brazilian society he posed as a mythical figure, provoking shock and curiosity in the audience, which always kept them interested.

Above: (2) Ney in his stage costume (Maia, circa 1970)

Moving over to television entertainment - another very important sector of Brazilian pop culture - it is also possible to start seeing representations of LGBTQ+ subjects, even though television channels also suffered heavily from censorship. One of the first personalities to do so was the Talent show host Chacrinha, who often dressed up as a woman and inserted sexual innuendos in every bit of the show during its exhibition in the 80s. From that onwards, there were more and more queer personalities in soap operas and TV shows. And the reason for that was simple: the polemic topic helped in the audience numbers - and therefore, profit. Actors that interpreted gay characters became nation-wide famous, all for performing very palatable version of real LGBTQ+ people, to please the public’s voyeuristic desires. The author suggests that this hygienization is mandatory for the continuous exotification of the public towards these ’strange loves’ that stayed in Brazilian’s imaginary.

Above: (3) The couple Niko (right, Thiago Fragoso) and Félix (left, Matheus Solano) in the prime time soap opera Amor À Vida.

In the same logic, LGBTQ+ characters also became the center of the joke. Many popular TV comedy shows had one or another sketch with their male actors cross-dressing or representing a very emasculated gay character. One persona in particular to highlight was Capitão Gay (Captain Gay), a Super-Man parody covered feathers who solved problems “no man or woman could solve” (Capitão Gay, 1981) with the help of a very dubious magic wand. The gay superhero was attacked both by the moralist, who thought this would promote homosexuality and by the LGBTQ+ community, which accused the character of perpetuating stereotypes. More recently, there was Ferdinando Show, an interview show featuring Ferdinando, a comic character who used the art of drag, musical performances and loads of gay slang in his talk show.

Above: (4) Capitão Gay (right) and his helper Carlos Suely (left) in their famous costumes. / Below: (5) Ferdinando, interpreted by actor Marcus Majella.

The trans community also had its representation on the TV screens. Rogéria was the first to appear, as a guest in Chacrinha’s Talent show. Her fame led her to receive the title of “the transvestite of the Brazilian family”. Nany People, another trans comedian, and actress followed the legacy of Rogéria and has been featured in plays and soap operas. Another celebrity to mention is Roberta Close. She started out as the ad girl for a closets campaign and later on she sold out 200k copies of a Playboy magazine (Kfouri, 1984). Close had the looks of the beauty standards for a woman at the time and, therefore, was an easy target for the objectification and projection of male desires. Nevertheless, Roberta got famous to the point of receiving backlash from both sides: the conservatives were outraged by the idea of having a trans woman as a national sex-symbol, while feminist groups saw on Close a clear representation of sexist male desire.

Above: (6) Roberta Close in the beginning of her career.

Back to the chronological order, in the 1990s the world suffered from the AIDs crisis and Brazil had its martyrs from popular music who carried out this cross. Cazuza and Renato Russo were famous names in the music industry, adored by the public (mainly the youth) as rock stars and came out as gay during the 80s. They were far from the stereotypical gay man propagated by the media, which allowed them to merge their romantic/sexual life as part of their regular public and creative career. Cazuza and Russo were HIV positive and made public through lyrics their experiences with the disease and sexuality, contrary to what older generations icons - such as Matogrosso (1992) and Veloso (Fraga, 1993) - did at the time, separating themselves to any comparison to the LGBTQ+ community.

Through this quick flashback, we can glance at the permissiveness of the queer representation in Brazilian mainstream culture. This phenomenon is dependent of a few factors: it is either a “polished” version that is in accordance with heteronormative standards, such as the looks of Roberta Close or the lack of similarities between Cazuza and the advertised gay man; or it represents something exaggerated and different enough to either spark exotification - like Ney Matogrosso’s performance - or to be the pun of the joke - as did Capitão Gay. This so-called ‘acceptance��� is according to the malleability of society to identify similarities that don’t offend the heteronormative system or differences so evident that make those individuals to be treated as something mysterious and possibly beyond-human. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize the path that these personalities built to contribute to the integration of the LGBTQ+ community outside of the margins and into pop culture.

References

Capitão Gay (1981) Viva O Gordo. Rede Globo, 9 March.

D'Araujo, M.C. (Unknown) Fatos e Imagens: artigos ilustrados de fatos e conjunturas do Brasil. Available at: https://cpdoc.fgv.br/producao/dossies/FatosImagens/AI5 (Accessed: 7 January 2020).

Fraga, P. (1993) ‘Caetano ataca New York Times no programa do Jô’, Folha de S.Paulo, 30 September.

Kfouri, J. (ed.) (1984) ‘Lídia Bizzocchi (especial: Roberta Close)’, Playboy, March.

Matogrosso, N. (1978) ‘Ney Matogrosso fala sem make up’. Interview with Ney Matogrosso. Interviewed by Vânia Toledo and Nelson Motta for Interview (n.5), May, p. 4-7.

Pereira, E. (1982) ‘Ney, em liberdade moral’, Journal da Tarde, 13 November, p.7.

Vaz, D. P. (1992) Ney Matogrosso: Um cara meio estranho. Rio de Janeiro: Rio Fundo Editora.

Figures list

1 - Para a caracterização, o figurino trazia brilho, meia arrastão e maquiagem pesada (2012) Available at: http://redeglobo.globo.com/globoteatro/bis/noticia/2013/09/relembre-momentos-marcantes-da-carreira-do-grupo-dzi-croquettes.html (Accessed: 7 January 2020).

2 - Maia, J. ( circa 1970) Ney Matogrosso, o showman brasileiro. Available at: https://imagesvisions.blogspot.com/2013/11/ney-matogrosso-o-icone-camaleao-do.html (Accessed: 7 January 2020).

3- Amor À Vida (2013) Rede Globo, 13 January, 21:00.

4- Viva O Gordo (1981) Rede Globo, 9 march.

5- Fernando Show (2015) Multishow, 10 August.

6- Fala cinco idiomas: o inglês, o francês, o alemão, o português e o italiano (2015). Available at: https://entretenimento.r7.com/famosos-e-tv/fotos/musa-dos-anos-80-roberta-close-aparece-com-o-rosto-irreconhecivel-em-rede-social-compare-06102019#!/foto/8 (Accessed: 7 January 2020).

0 notes