#replica of David Hockney's work

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Say Hello to Hockney

(digital drawing replica, collage)

0 notes

Text

The Camera Obscura and Painting

Unit 9

Research

Since the advent of photography, there has been a somewhat uneasy relationship between photography and painting. Even though the word, "photography" means "drawing with light" when translated from its Greek roots, many painters are reluctant to admit that they work from photographs. But many painters now use them as references, and some even work from them directly, by enlarging and tracing them.

Some, like well-known British artist David Hockney, believe that Old Master painters including Johannes Vermeer, Caravaggio, da Vinci, Ingres, and others used optical devices such as the camera obscura to help them achieve accurate perspective in their compositions. Hockney's theory, officially called the Hockney-Falco thesis (includes Hockney's partner, physicist Charles M. Falco), postulates that advancements in realism in Western art since the Renaissance were aided by mechanical optics rather than merely being the result of improved skills and abilities of the artists.

The Camera Obscura The camera obscura (literally "dark chamber"), also called a pinhole camera, was the forerunner of the modern camera. It was originally a darkened room or box with a small hole in one side through which rays of light could pass. It is based on the law of optics that states that light travels in a straight line. Therefore, when traveling through a pinhole into a dark room or box, it crosses itself and projects an image upside down on the opposite wall or surface. When a mirror is used, the image can be reflected on a piece of paper or canvas and traced.

It is thought that some Western painters since the Renaissance, including Johannes Vermeer and other Master painters of the Dutch Golden Age that spanned the 17th century, were able to create very realistic highly detailed paintings by using this device and other optical techniques.

Documentary Film, Tim's Vermeer The documentary, Tim's Vermeer, released in 2013, explores the concept of Vermeer's use of a camera obscura. Tim Jenison is an inventor from Texas who marveled at the exquisitely detailed paintings of the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675). Jenison theorized that Vermeer used optical devices such as a camera obscura to help him paint such photorealistic paintings and set out to prove that by using a camera obscura, Jenison, himself, could paint an exact replica of a Vermeer painting, even though he was not a painter and had never attempted painting.

Jenison meticulously recreated the room and furnishings portrayed in the Vermeer painting, The Music Lesson, even including human models accurately dressed as the figures in the painting. Then, using a room-sized camera obscura and mirror, he carefully and painstakingly proceeded to recreate the Vermeer painting. The whole process took over a decade and the result is truly amazing as seen in the trailer of the documentary Tim's Vermeer, a Penn & Teller Film.

David Hockney's Book, Secret Knowledge During the course of the filming of the documentary, Jenison called upon several professional artists to assess his technique and results, one of whom was David Hockney, the well known English painter, printmaker, set designer and photographer, and master of many artistic techniques. Hockney has written a book in which he also theorized that Rembrandt and other great masters of the Renaissance, and after, used optical aids such as the camera obscura, camera lucida, and mirrors, to achieve photorealism in their paintings. His theory and book created much controversy within the art establishment, but he published a new and expanded version in 2006, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, and his theory and Jenison's are finding more and more believers as their work becomes known and as more examples are analyzed.

Does It Matter? What do you think? Does it matter to you that some of the Old Masters and great painters of the past used a photographic technique? Does it diminish the quality of the work in your eyes? Where do you stand on the great debate over using photographs and photographic techniques in painting?

https://www.liveabout.com/camera-obscura-and-painting-2578256

0 notes

Text

Week 9 - 20200714

> Lesson 6 1. Keith Haring - an American artist whose pop art and graffiti-like work grew out of the New York City street culture of the 1980s

2. Claes Oldenburg - an American sculptor, best known for his public art installations typically featuring large replicas of everyday objects

3. Robert Rauschenberg - an American painter and graphic artist whose early works anticipated the pop art movement - well known for his "combines" of the 1950s, in which non-traditional materials and objects were employed in various combinations - a painter and a sculptor, and the combines are a combination of the two, but he also worked with photography, printmaking, papermaking and performance

4. Richard Hamilton - an English painter and collage artist - pop art

5. Roy Lichtenstein - an American pop artist - inspired by the comic strip - influenced by popular advertising and the comic book style

6. Peter Blake - an English pop artist, best known for co-creating the sleeve design for the Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and for two of the Who’s albums - best known British pop artists - considered to be a prominent figure in the pop art movement

7. Andy Warhol - an American artist, film director, and producer who was a leading figure in the visual art movement known as pop art - best known works include the silkscreen paintings

8. David Hockney - a British painter, draftsman, printmaker, stage designer, and photographer - an important contributor to the pop art movement of the 1960s, he is considered one of the most influential British artists of the 20th century

> 3As 1. Awareness 意识 - go and look around - talk to people

2. Awakening 醒悟 - learn from people - think and learn

3. Autonomy 自主 - passion - can imitate people works - find own voice from inspiration - continue develop - expand

> DESIGN is to design a DESIGN to produce a DESIGN

> the heart of the problem is the problem of your heart

> Project Review - Final (Poster)

> Feedback - minor refine of the maze

0 notes

Text

Blog·8:Ipad/Iphone and Art

In my last blog post, I talk about digital art, and today I want to continue my research on this topic. 80% of my illustrations are done through iPad, thus I would like to introduce creating with iPad as the medium in this article.

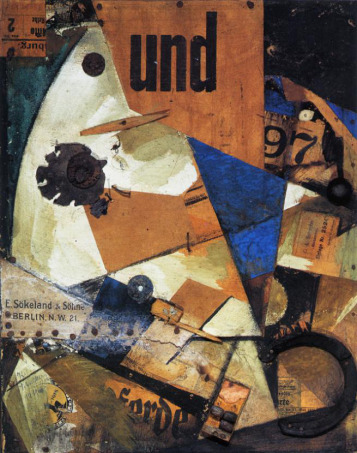

I read a large number of books about creating with iPad, among which one of the authors states that a new art movement would usually be replaced by another. In this short period of 20 years, realism gives way to impressionism, and surrealism and pop art are separated from Dadaism. Marcel Duchamp’s readymades and Kurt Schwitters’ creative collages are outmoded by the idea of surrealists, who come back to re-emphasize the importance of technical proficiency. Dadaists and surrealists make place for abstract expressionists, pop artists and conceptual artists. If artistic freedom is the origin of the art movement, the artistic freedom in the 21st century brings art movement to a new level. Through the powerful network, the interaction and communication of this art movement are beyond the imagination of artists in the past.

Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain ”

Kurt Schwitters’collages

In the past, people needed to make a chart to connect each art movement. But now the art of digital tools, such as the iPhone and iPad, is influenced by the diversity of the world and the artists who share the same artist studio. The iPhone art movement encompasses the artistic styles of artists all over the world, including realists, impressionists, dadaists, cubists, surrealists, abstract expressionists, pop artists, concept artists, technical artists, music artists, video artists, and craft artists. What they have in common is that they use the iPhone or iPad and use any of their skills to create art.

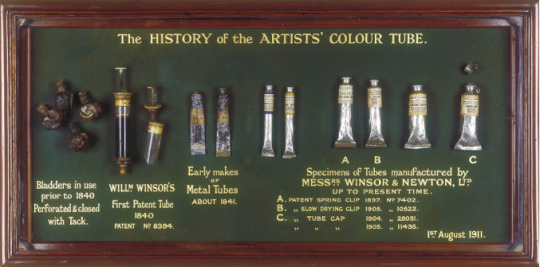

There are certain times when the birth of a new art movement needs to be based on the destruction of another. However, the emergence of digital illustration does not disrupt any art movement. Application developers adopt the latest and greatest tools to provide a creative platform for the public. New technology creates new art. In the long history, people always create technology. For instance, in 1841, the first metal paint tube was first invented by an American oil painter, who applied for a patent for the collapsible metal paint tube made of tin, a way to bring the pigments to the outdoor for use. These tubes were actually syringes, which were used by squeezing the paint. In addition, this also made the storage time of the pigments greatly longer, which not only increased the flexibility of artists, but also allowed them to use a larger palette. Before the first metal paint tube came out, artists had to play the role of chemists, grinding pigments themselves and mixing them with oil and paint thinners.

In order to make painting outdoors easier, artists had to put the paint mixture in the pig bladder. Unfortunately, even in this way, the paint dried out quickly.

Therefore, metal paint tube was a new technology at that time, which enabled impressionist artists to create art outdoors, promoting the creation of the most popular movement in the art history.

The artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir once said, "without paint in tubes, there would have been…nothing of what the journalists were later to call Impressionists". In the field of digital art, the technology that drives artists is not the metal paint tube, but the introduction of hardware and software.

Newspapers, life magazines and supplements were the most popular publications until the tablet computer came out in 2010. However, the rapid development of digital publications today offers new opportunities for designers, publishers and advertisers. Including website, mobile phone, Android tablet computer, iPad, and a wide variety of applications, all enable to designers to add mobile images and interactive contents to digital newspapers and magazines. Many people carry mobile devices with them, giving publications more followers via digital transmission than print editions.

The earliest digital publishing websites were mainly page sites with PDF documents, which could be viewed as quickly as traditional paper newspapers or magazines, but required large memory spaces and available fonts. Conde nast, an American publisher, developed its own customized software without using the external software system, and produced a series of magazines such as Wired, GQ and Vanity Fair. In the 1990s, HTML emerged as a computer-coding language, which made it convenient for designers to embed mobile content into websites, and then browsers read tags and convert them into texts and images for the public to view.

With the development of interactive design technology, a variety of applications attract a large number of advertisers to add mobile images and interactive content to advertisements. With the launch of the iPad in 2010, digital publishing has become a better and more portable way of publishing. The iPad puts all the editorials and life needs into a portable device, including email, photos, shopping, surfing the Internet, and reading.

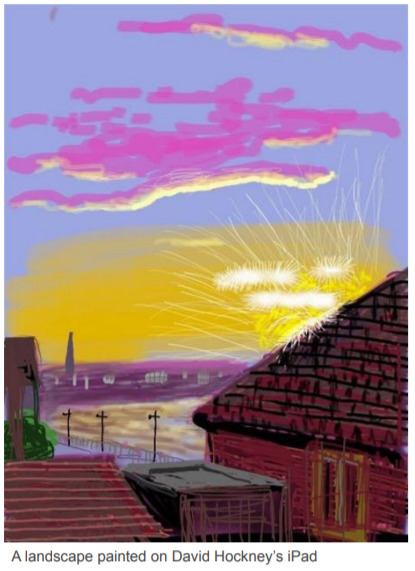

The painting above is by a famous artist Hockney on the iPhone, who has illustrated hundreds of works since he began using apple devices in 2008. He has been creating his own works on the iPad since the spring of 2008, some of which are on display at the Fleurs Fraiches at the Fondation Pierre berge-yves Saint Laurent, Paris, from October 21 to January 30. He often sends illustrations drawn on his iPhone to his friends. The iPhone is a new medium for him, with unlimited possibilities. He experiments with this unorthodox method of painting, choosing to use his fingers instead of pens. Hockney mainly paints with the edge of his finger, because the iPhone is so sensitive to heat that he can't use the whole finger. Finger painting is more than just touching. It is difficult to control the area where a finger touches the electronic screen, the lines can bend.

References:

Leibowitz, D.S. 2013, Mobile Digital Art: Using the iPad and iPhone as Creative Tools, Taylor and Francis, Independence.pp.2-3

Caldwell, C. & Zappaterra, Y. 2014, Editorial design: digital and print, Laurence King Publishing, London.pp.23-24.

Gayford, M. (2010). David Hockney's iPad art David Hockney explains why the iPhone and iPad inspire him. [online] Prod-images.exhibit-e.com. Available at: http://prod-images.exhibit-e.com/www_richardgraygallery_com/2010_DH_Telegraph.pdf [Accessed 15 Dec. 2019].

Tate. (2019). ‘Fountain’, Marcel Duchamp, 1917, replica 1964 | Tate. [online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/duchamp-fountain-t07573 [Accessed 15 Dec. 2019].

Tate. (2019). Kurt Schwitters 1887-1948 | Tate. [online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/kurt-schwitters-1912 [Accessed 15 Dec. 2019].

Winsornewton.com. (2015). From the Archives: The History of the Metal Paint Tube. [online] Available at: http://www.winsornewton.com/na/discover/articles-and-inspiration/from-the-archives-history-of-the-metal-paint-tube [Accessed 15 Dec. 2019].

Gayford, M. (2010). David Hockney's iPad art David Hockney explains why the iPhone and iPad inspire him. [online] Prod-images.exhibit-e.com. Available at: http://prod-images.exhibit-e.com/www_richardgraygallery_com/2010_DH_Telegraph.pdf [Accessed 15 Dec. 2019].

0 notes

Text

Multiple Images

Task 1 – Selected Multiple Images and Techniques Used

1. Typology

Transform everyday objects into a thing of art. The creation of a typology usually has one of two intentions.

· To compare and highlight differences and/or similarities between subjects that do share a visual relationship.

· To create a relationshipbetween subject that share no obvious visual relationship.

The ability to compare the similarities and differences between the components is important and for this reason artists/photographers often use a grid, layout to showcase their work.

Working in Germany between the first and second world wars, August Sanderundertook typological study called The Physiognomy of Our Time. He classified German society into types based on class and social standing, using the following major categories – The Farmer, The Skilled Tradesman, The Woman, Classes and Professions, The Artists, The City and The Last People. He wasn’t interested in taking photographs that revealed the uniqueness of each person, rather he saw them as archetypes and employed a style that emphasised this aspect.

The Physiognomy of Our Time. ,August Sander

Sander influenced generations of photographers, among them the couple Bernd and Hilla Becker who in the 1950s they began documenting rundown and disappearing industrial architecture – blast furnaces, water towers, foundries. Presenting the work in a straightforward grid format, each picture was taken under a uniform grey sky at the same time of day, from the same distance and angle – allowing the images to be easily compared and classified.

Bernd and Hilla Becker

2. Triptych

Is a three-fold piece of art that is typically hinged together as carved panels side by side. The artistic works complement each other with similar subjects or a relatable message. Photographers also use the triptych style, using it to arrange three of their images within one frame with clear borders between them, or by using a separate frame for each photo and mounting them on the wall next to each other. Triptych photography might involve taking one picture and splitting it into three different parts as in the image of the Manhattan Skyline or shooting three separate photos that are related.

JR Wheatley – Manhattan Skyline from Brooklyn Bridge Park

Ashleigh Jarvis – Books Grid

3. Joiners

This style was created by British artist David Hockney in the early 1980s. He called the collages ‘joiners’ and spawned a technique that has remained popular ever since.

To achieve this, you need to shoot images that capture small areas of a larger scene. There are two main guidelines:

· Each image needs to overlap both the one taken before and the one after. This includes those to the left, right, above and below. The process to ensure this is very simple, and to make matters even better the odd missing image can often be replaced with another.

· Position of shooting must remain consistent. Once you begin shooting you should remain standing in the same spot, only turning on the spot to capture the wider landscape around you.

Pear Blossom Highway – David Hockney

David Hockney Style Image

Task 2 – Which Image Resonates?

The image which I have chosen is Last Suppers taken by London based photographer who normally works in advertising, James Reynoldsin 2009 where former death row prisoners were represented not by their portraits or more traditional photojournalistic documentation, but by their choice of last meal.

Last Suppers

To me this work is not only visually eye caching but provokes thought on a number of levels. This is the last thing prisoners would see before they die. What would be my last meal, what does is say if anything about the prisoners, their crime, thoughts before death. What wold their families feel at this representation? What are my thoughts on the death penalty and death itself?

Essentially it is a documentary, and although Reynolds is not the only photographer to have explored such an issue there is something eye catching about the way it has been woven into typology. The birds eye view, the orange trays which were replicas of the ones they actually use in maximum security prisons, the symmetry of their presentation and the somewhat bizarre selection of meals makes it an intriguing image.

0 notes

Photo

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hamilton-diab-ds-101-computer-t07124

Diab DS-101 Computer is a large object by the British artist Richard Hamilton that consists of a computer. It is comprised of three grey metallic-looking blocks, stacked on top of one another and separated by 1 cm spacers, which are placed on a fourth black block that sits directly on the gallery floor. The uppermost block features the logo of the computer’s Swedish manufacturer Diab (Dataindustrier AB), as well as a green LED light and a drive unit containing a floppy disk drive, a hard drive and a backup drive. On the block beneath this, which is the largest of the four, are featured two further LEDs, the top one glowing red or green and the lower one green, and this block’s grey casing conceals the computer’s central processing unit. The third grey block, which sits below this, is completely plain and contains the power supply.

This work was initiated in 1983 when Hamilton, who at the time was living and working in Oxfordshire in the UK, was invited by the computer company Ohio Scientific (acquired by Diab in the mid-1980s) to collaborate on the design of a minicomputer. A prototype of the work, with an existing Diab circuit board, was first exhibited in the exhibition Antidotes to Madness?: Richard Hamilton, Nam June Paik, Ree Morton, Hannah Collins and Piotr Sobieralski at Riverside Studios in London in 1986, and the final version was completed in 1989. Hamilton designed the exterior of the computer, dividing it into three sections according to function, and the UNIX operating system that it runs. At the time the machine was very advanced, with a specification that equalled an existing Diab computer that was three times its size. However, while the company planned to produce ten of these computers, only six were ever made.

The title of the work is the name of the computer product and states the model number in Diab’s standard format, and Hamilton’s use of 1s and 0s, which make up binary code on which computers run, emphasises the item’s function. The original title given to the computer when it was conceived for Ohio Scientific was ‘01-110’, a formulation that visually resembles the word ‘OHIO’. While the ‘DS’ of the final title is a standard model number, it also resonates with the interest in the Citroën DS 19 car held by British architects Alison and Peter Smithson and the French philosopher Roland Barthes. Hamilton and the Smithsons had been members of the London-based Independent Group in the 1950s, a circle of artists who were fascinated by modern technology and design. This interest continued throughout his career: in 1979 Hamilton created Lux 50 – functioning prototype (private collection), a high-fidelity amplifier in the form of an image of a ‘hi-fi’ painted onto a very thin amplifier, in collaboration with the Japanese electronics manufacturer Lux. Hamilton was also quick to incorporate developments in computing into the production of his art. He was an early adopter of the Quantel Paintbox programme, which was also used by the British artist David Hockney, and later in his career Hamilton used Adobe Photoshop in his work.

Collaborations were not uncommon in Hamilton’s practice, but from an artistic point of view this computer work, like the Lux amplifier, reflects his interest in the readymade object in art. Once photographed with one of the first readymade artworks in the background – Marcel Duchamp’s famous Fountain 1917, replica 1964 (Tate T07573) – the Diab DS-101 does not entirely conform to the category of the readymade, as it remains functional despite being on display in a gallery. As is explained in the Antidotes to Madness? catalogue: ‘The computer enters the gallery not as an artwork, but providing a function. Hamilton makes available to the viewer a “menu” of information directly relevant to his work in general and more specifically to the works at Riverside’ (Paley 1986, unpaginated). Hamilton insisted that the machine should be operational as a computer when it was put on display, ‘rather than simply sitting as a sculpture in a gallery’, until technical obsolescence rendered this impossible (Nicholas Serota in a letter to Eddie Thordèn, 26 February 1992, Tate Acquisition File, Richard Hamilton, PC101.1). Although visually similar to the minimalist stacked sculptures of American artist Donald Judd (see, for instance, Untitled 1980, Tate T03087), the critic Alice Rawsthorn has noted that Diab DS-101 Computer is more comparable to furniture designed by Judd, which also question the divide between art and design as, unlike equivalent products not created by well-known artists, they are displayed in art galleries (Rawsthorn in Godfrey, Schimmel and Todolí 2014, p.133).

In 1987 a graphics board and colour graphics terminal that were not designed by Hamilton were added to some of the Diab DS-101 models to allow viewers to interact with coloured pictures and information about Hamilton’s work, as was the case when another version of the work went on display at the artist’s 1992 retrospective at the Tate Gallery, London. In 1995 Hamilton proposed that the machine might support Tate’s first ever website, or be connected with other examples of the same computer in the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen, to create a networked artwork, but such plans did not come to fruition (see Richard Hamilton, letter to Tate curator Richard Morphet with attached diagram proposing linking Tate computer to Stockholm, Copenhagen, Northend and the world, undated [April 1995?], Tate Acquisition File, Richard Hamilton, PC101.2).

[Emphasis Mine]

Addendum: Moderna Museet catalogue page for Diab DS-101

0 notes

Text

How to Find Your Artist Ancestors - Artists Network

Who Inspires You?

As artists, we almost have this inherent tourist attraction to our craft, to our requirement to produce. And, all of us have something or somebody that has fueled this enthusiasm. For many artists, the works of others steer the method they approach their own art. https://www.artistsnetwork.com/store/the-joy-of-acrylic-painting?utm_source=artistsnetwork.com&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=arn-mwo-bl-180110-JoyAcrylicPainting" target= "_ blank "rel= "noopener" > The Happiness of Acrylic Painting. In this inside look, she shares how to gain from your Artist Ancestors and also strolls us through an enjoyable, detailed demonstration influenced by one of her own artist influencers, Henri Matisse. Take pleasure in!

Knowing from your artistic forefathers is great. Finding out from the finest modern art instructors in the field of great art today is the chance of a lifetime if you desire to develop your&passion for painting and drawing. Come join us on Artists Network TELEVISION! Discovering Your Artist Ancestors Every artist has private tastes in artists they find inspiring. For example, the works of three really various artists-- David Hockney, Henri Matisse and Georgia O'Keeffe-- make my heart race for very various reasons. There are numerous others, even renowned artists, who leave me definitely cold. I'm sure you are the exact same.

Artists who resonate with us are what I call our Artist Ancestors. I think it's beneficial in our advancement as artists to believe about why. The majority of us understand intuitively which artists they are when we see their work. Take note of that signal so you can take the next step.

To gain from the work of an Artist Ancestor you love, apply the analytical part of your brain to evaluate what it is that makes his/her work so enticing and whether you can apply that to your own work. When you integrate components from your Artist Ancestors with your own interpretation, you are developing your own painting style.

From Motivation to Canvas

Henri's Window by Annie O'Brien Gonzales, acrylic on canvas

All artists are an amalgam of motivation from other artists and innovations of their own. Once you have analyzed the elements that you wish to include in your own work, you can move from replica to development utilizing those elements.

Study your Artist Ancestors, gain from them and take away concepts to include into your work. How can you consist of some of their ideas in your own work? And what about copying? Is it a bad thing? It is a fact that all artists through time have found out from other artists. The technique is to take what you discover and make it your own.

If you have an art sketchbook, brainstorm a list of 3 to 5 artists who consistently attract your attention. For each Artist Forefather, create a complete page in your sketchbook with the artist's name at the top of the page and connect a reproduction of among your favorite pieces of that artist's work.

Study the work and write down what you find most attractive about the work. Some questions to ask yourself may be:

Repeat this procedure for each artist on a brand-new page in your art sketchbook. Gather all of the aspects that bubbled up in your analysis of your Artist Ancestors onto one page, and see which ones keep repeating and how you might attempt these concepts out in your own work. This will give you insight into your particular painting design and a direction for future work. Now, let's have some enjoyable.

Paint Like Your Artist Ancestor

This project is developed to provide you an opportunity to attempt out the strategies of your favorite artist in your own work. For this presentation, I painted in the style of Matisse, a master expressionist painter. I love his work and gravitate to numerous of the aspects including the warm colors and loose brushstrokes.

Henri Matisse's Nature Morte, Serviette A Carreaux. Picture thanks to DOUG KANTER/AFP/Getty Images

For your project, select a painting from among your Artist Ancestors, specify the components of his/her work and after that paint utilizing that technique. You will find out a lot and will have the ability to consciously decide whether that technique will work for you.

Analyze the style of the painting you are using as your inspiration and tape your ideas in your sketchbook, comparable to my example for this project:

What you will require to finish this tutorial:

1. Evaluating Your Artist's Style

Select an Artist Ancestor who motivates you. What piece of work makes you swoon? I chose Henri Matisse's painting Table with Fruit.

Evaluate his/her use of the 5 elements of painting: line, shape, color, value and texture. Evaluate the design concepts stressed by that artist and how these play a part in his or her work.

Step 1

2. Picking Your Color Palette

Create a color scheme utilizing your inspiration painting as a referral. Ensure to keep this reference close by.

Step 2

3. Starting Your Sketch (or Underpainting)

You can choose to copy the structure of the motivation painting or choose your own subject matter to be painted in the color combination and design of your Artist Ancestor.

After studying Matisse's work, I sketched my composition onto the canvas without an underpainting since I had actually seen he sometimes let the white canvas show in places.

Action 3

4. Determining Your Painting Design

For Matisse's style, I picked to paint outlines of the topic with black paint and a little round brush.

Describe the image by including variations on color and thicker paint.

7. Working on the Details

Include smaller sized information to separate the large shapes utilizing your Artist Ancestor's painting as a referral point.

The Reveal

My completed painting reflects my study of the line quality and color utilized by Matisse, but I utilized my own images.

Finished Art

Who are your Artist Ancestors? Share them with us in the comments listed below! And then make sure to join us on Artists Network TELEVISION, where the best of our contemporary "artist ancestors" are teaching us what they understand!

0 notes

Text

Tim’s Vermeer

- Engineer/Inventor Tim Jenison attempts to recreate Vermeer’s Music Lesson, after reading David Hockney’s book Secret Knowledge

- In Hockney’s book he suggests that artists were using camera obscura to achieve detailed, camera like images

- The method includes using a darkened room with a small hole and lens. The subject is positioned outside the dark room, where it is projected backwards and upside down inside the dark room

- In order to replicate Vermeer’s work, Tim Jenison had to supply pigments which Vermeer would have used and make his own paint

- He then found the best way to imitate Vermeer’s work by placing mirrors above the canvas at a 45 degree angle, where he could consistently color match and create an identical image with a lens aka camera lucida

- In the process of attempting to recreate Vermeer’s Music Lesson, Jenison constructed an exact replicate of Vermeer’s art studio inside of a warehouse.

- Using the camera lucida method Jenison was able to paint an exact replica of Music Lesson, despite many different set backs. All the while discovering that the curvature of the lens he used also created a curvature on the painting, where it is discovered that Vermeer made the same mistake

- The painting itself took 7 months to finish.

- After its completion, Jenison took the Painting to England to present it to David Hockney, who originally suggested that artists used a lens to create camera image like paintings. Hockney expressed the accuracy of Jenison’s painting to Vermeer’s work

0 notes

Text

2018 Gift Guide: Art

Art is such a wonderful gift to give someone, especially for someone who might not buy it for themselves, whether they see it as an extravagance or they just can’t afford it. Whatever the reason, having someone thoughtfully select a piece of art out for them is pretty special and most definitely unforgettable. Read on to see a variety of types of art, from prints, sculptures, figures, and paintings, all pieces most anyone would love to own.

Anyon x Elyse Graham – Nicasio Vase \\\ $1250 Part of the Blithe Collection, this resin and plaster vase is a one-of-a-kind, as is all of Graham’s handmade work. The faceted exterior displays shades of lavender while the interior pops with a bright yellow making for a beautiful and unique display piece.

Eames House Exterior Photography Print by Charles Eames \\\ Starting at $35 Taken by Charles Eames himself in the early 1950s, the photo shows the south side of the Eames House with the front door and reflections of the trees all through his perspective. Plus you can customize it by choosing the type of paper and size of the print, as well as have it professionally framed.

Teak Duck & Duckling Model Set by Hans Bølling for ARCHITECTMADE \\\ $238 Based on a headline-making story from 1959 in Copenhagen where a family of ducks crossed a busy street during rush hour traffic, this adorable pair of figures is handmade from solid teakwood making for a charming yet whimsical display on any shelf or tabletop.

David Hockney. A Bigger Book. Signed Limited Edition from TASCHEN \\\ $2500 For the ultimate Hockney or modern art fan, this massive illustrated book spans over 600 pages revisiting more than 60 years of work, from teenage years through his 1960s breakout in London to LA pools in the 1970s to most recent works of portraits, iPad drawings and landscapes. This limited collector’s edition even comes with a Marc Newson bookstand for display.

U.S.A. Song Map Print from Dorothy \\\ £30 Dorothy has a way of cleverly giving maps a new purpose. This particular one is a fun, vintage style map featuring over 1,000 songs that will take you through a musical journey across the United States by using songs with states, cities, rivers, mountains, and landmarks in the title. Don’t let the £ price scare you as they ship internationally!

Farnsworth House by Chisel & Mouse \\\ $1550 It doesn’t get much more iconic than the Farnsworth House and this plaster wood 3D printed model is a super fun replica for any architecture lover. The model weighs approximately 17.5 lbs. and measures 11″ deep by 18.5″ wide making it a hefty and impressive model for display.

Training Mission #241 painting by Michael Moncibaiz \\\ $150 While slight in size at a mere 8″ x 6″ x 1.5″, this gouache, acrylic, and graphite piece packs a beautiful punch with shades of yellow, white, and black in a minimalist composition that will add seriously visual interest to any empty spot on the wall.

Open Eye Object by MQuan \\\ $290 The eye has long been a symbol for protection and visual insight and this hand-painted ceramic eye makes the perfect piece for someone to add to their home with its storied past.

Columbia Cargo Print by Jorey Hurley \\\ $249 A minimalist print that still evokes a playful sense of wonder with its hand-drawn blue lines that feel as if the boat and water are actually moving along. It’s soft but graphic making it a visually pleasing piece for anyone’s collection.

Ole AP/50 (2016) by Stephen Ormandy \\\ AUD $1000 And last but not least, a piece that surely holds its own with a bold color palette and organic shapes that Ormandy is so famous for. This limited edition fine art reproduction is a more affordable option for those who can’t afford an original painting but want to own his vibrant work.

via http://design-milk.com/

from WordPress https://connorrenwickblog.wordpress.com/2018/11/21/2018-gift-guide-art/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hyperallergic: Paintings that Revel in the Wonder of Our Domestic Spaces

Becky Suss, “August” (2016) (all images ©Becky Suss, courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York unless otherwise noted)

Pristinely kept and replete with beautiful objects, the domestic spaces that Becky Suss paints are like photographs in interior design magazines that leave you coveting the lifestyles of strangers. But unlike those glossy spreads, the Philadelphia-based artist’s oil paintings feel familiar, even though you’ve never stepped inside these particular bedrooms, libraries, and hallways before.

Seven of these large-scale works are currently on view at Jack Shainman gallery for Suss’s solo show, Homemaker, where they boldly usher the quiet comforts of home into the sterile, white-walled space. Books, seashells, and other evocative trinkets such as a saxophone mouthpiece line shelves; a sliced grapefruit nestles in a bowl like a ritual breakfast for one; a closet door stands ajar to reveal soft flannel shirts and an unmarked box of potential secrets.

Becky Suss, “Red Apartment” (2016)

Suss began painting her detailed rooms after her grandparents’ passings, memorializing the rooms of their house in vivid oils as a way to process her sudden inheritance of their countless belongings. For Homemaker, her new paintings are less faithful to reality: the rooms blend actual, lived spaces with Suss’s imagined visions as well as details she looked up online.

In the expansive “August” (2016), for instance, a small library on the left emerges from memories of her therapist’s office, while the marble mantlepiece in the central living room is a copy of one in her current house. The view out the window of apartment buildings is a replica of that in David Hockney’s “Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy,” minus the British painter’s wispy foliage. For “Blue Apartment” (2016), Suss drew upon the architecture of an Upper East Side apartment belonging to her parent’s friends, and filled the cozy bedroom with a number of her personal possessions.

These diverse sources aren’t made explicit, but Suss’s paintings immediately feel unreal because of their flatness, broad perspectives, and use of three-fourths scale — which makes these rooms seem enterable from afar, but up close, are clearly diminutive, and even dollhouse-like because of Suss’s playful colors. But her careful and deliberate construction of them also lends them their sincerity and heartfelt associations of a relatable home. Her paintings celebrate the everyday environments that we may take for granted, and urge us to behold the wonder in our domestic spaces, which are stages for us to air our identity without bars. Our gaze is kept moving by the many curious objects and busy patterns, which encourage a meandering of another kind — to mine our own memories for places that hold meaning. Further inducing this psychological wandering are Suss’s many connective furnishings, like doors, archways, mirrors, and windows that create continuous realms, like abstract, labyrinthine spaces of the mind.

Becky Suss, “Hallway” (2017)

The show also features about a dozen small-scale paintings of book covers and decorative objects, such as vases and wall art, that appear in her larger paintings. These extend the fictional architectural spaces into the gallery so it, too, becomes her own constructed, personal space — one that we can actually walk around in — with these particular, chosen articles speaking to her own associations of home.

Two paintings of embroidery are especially personal: the original needlepoint of an American flag by her great-grandmother who was a suffragette; and one of the Irish phrase of allegiance, “Erin Go Bragh,” that hung in her grandmother’s house. Suss painted them partly because she wanted to honor her own family of women homemakers — a word, she told me, for which she has a slight disdain because of its traditionally gendered meaning. With Homemaker, she reclaims the term, devoting herself to the domestic space, but to domains that are utterly of her own and that are fully under her control. The title is also a proud assertion of her sustained labor and successful career as a working female artist. More broadly, it is a testament to her power and presence today in a system that has always catered more to men.

Becky Suss, “Bathroom (Ming Green)” (2016)

Becky Suss, “Bedroom with Peacock Feathers” (2017)

Becky Suss, “Home Office” (2016)

Becky Suss, “Blue Apartment” (2016)

Becky Suss, “Still Life” (2017)

Becky Suss, “Stars and Stripes For-Ever” (2016)

Becky Suss, detail of “August” (2016) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Becky Suss, detail of “Bathroom (Ming Green)” (2016) (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Installation view of Becky Suss: Homemaker at Jack Shainman Gallery

Becky Suss: Homemaker continues at Jack Shainman Gallery (513 West 20th St., Chelsea, Manhattan) through June 3.

The post Paintings that Revel in the Wonder of Our Domestic Spaces appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2rwb1vP via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

End of Art, Again?!

[Photo: Andy Warhol in 1964. Photo by Mario De Biasi/Mondadori/Getty]

There are more artworks, and more types of artwork, being produced than ever before. Galleries are widespread and – in some countries – free. Major art prizes, and major artists, receive frequent press attention. With all this abundance, it seems nonsensical to suggest that art had ended. It’s not clear that the claim even makes sense – how could art come to an end?

But this idea is not as obviously wrong as it seems. Talented and insightful philosophers of art have taken this claim quite seriously, even while acknowledging that artworks will continue to be produced in larger numbers, and in new and exciting ways. When these philosophers claim that art has ended, they are not saying that there will be no new artworks. Their claim is quite different. They are telling us that art has some kind of goal, or line of development, which has been completed; plenty more will happen in art, but there is nothing left to achieve. Just as Francis Fukuyama claimed in 1989 that history had ended – meaning not that nothing more would ever happen, only that all ‘viable systematic alternatives to Western liberalism’ had been exhausted – so too some philosophers claim that art as a practice will continue, but has no more ways of progressing. Two of the more prominent philosophers to have made this sort of argument were G W F Hegel in the early 19th century, and Arthur Danto in the late 20th century.

Hegel was, in many ways, the father of what we now call the history of art. He gave one of the earliest and most ambitious accounts of art’s development, and its importance in shaping and reflecting our common culture. He traced its beginnings in the ‘symbolic art’ of early cultures and their religious art, admired the clarity and unity of the ‘classical’ art of Greece, and followed its development through to modern, ‘romantic’ art, best typified, he claimed, in poetry. Art had not just gone through a series of random changes: in his view, it had developed. Art was one of the many ways in which humanity was improving its understanding of its own freedom, and improving its understanding of its relationship to the world. But this was not all good news. Art had gone as far as it could go and stalled; it could, according to Hegel’s Lectures on Aesthetics (1835), progress no further:

The conditions of our present time are not favourable to art […] art, considered in its highest vocation, is and remains for us a thing of the past.

In 1835, Hegel claimed that art had ended. Almost exactly 10 years later, the German composer Richard Wagner premiered Tannhäuser in Dresden, the first of his great operas; the beginning in earnest of a career that would change musical composition forever. Less than a century after Hegel’s claim, the visual arts saw the onset of Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism and Fauvism, among other movements, and literature, poetry and architecture were deeply changed by Modernism.

In 1964, Danto attended an exhibition at the Stable Gallery in New York. He came across Andy Warhol’s artwork Brillo Boxes (1964) – a visually unassuming, highly realistic collection of plywood replicas of the cardboard boxes in which Brillo cleaning products were shipped. Danto left the exhibition dumbstruck. Art, he was convinced, had ended. One could not tell the artworks apart from the real shipping containers they were aping. One required something else, something outside the artwork itself, to explain why Warhol’s Brillo Boxes were art, and Brillo boxes in the dry goods store were not. Art’s progress was over, Danto felt; and the reign of art theory had begun.

We could ask ourselves whether these claims were false – but a better question is, what would it mean for these claims to be true? What do philosophers mean when they say art has or will come to an end? Is it just hyperbole? And why does art keep ending, for philosophers, while the rest of us see it carrying on, taking new directions?

In his Analytical Philosophy of History (1965), Danto drew attention to two different kinds of endings. We might claim that a narrative has ended; or we might say that a chronicle has ended. This is an important distinction. A narrative has a kind of structure – for example, I might describe to you how I (in some other possible world, alas) learned to manage my money properly. I would begin by describing the debt I fell into, and the advice I sought; the strategies I learned from certain books; and the tricks I employed to keep track of my outgoings. It would be a story about how I solved a certain problem; and once the problem was solved, the story ends.

A chronicle, by contrast, is just a series of events, with no structure – the events simply follow one after the other. The chronicle of my life includes every event that occurs in it – no matter how trivial – and will end only when I die. A chronicle ends only with the disappearance of the thing we are describing.

For Hegel, and Danto, art’s narrative had ended; it had progressed as far as it could in solving the task it had set itself. But art’s chronicle would never end: there would be new artworks for just as long as there were human beings to create them. Art’s end, in this sense, was a good thing. Art was released from labouring away at a task (given by the narrative); it was now free to be anything. For Hegel, art could revisit and re-use all the many tools and techniques the history of art had thrown up, and recombine them at will:

In this way, every form and every material is now at the service and command of the artist whose talent and genius is explicitly freed from the earlier limitation to one specific art-form.

For Danto, likewise, the artist should be overjoyed, and not discouraged, by the end of art. In The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art (1986), he wrote:

As Marx might say, you can be an abstractionist in the morning, a photorealist in the afternoon, a minimal minimalist in the evening. Or you can cut out paper dolls or do what you damned please. The age of pluralism is upon us. It does not matter any longer what you do, which is what pluralism means. When one direction is as good as another direction, there is no concept of direction any longer to apply.

For art to end, then, is for art to be released. Art no longer had to grind away at solving a task. But this still leaves the unanswered question: what does it mean for art to have a task?

Hegel’s answer to this question is complex. Its central motor is the claim that human life, including human culture, is underwritten by a collective principle of self-consciousness, known as Geist. (Geist, a notoriously tricky German term to translate into English, is most often rendered as ‘mind’ or ‘spirit’.) It is Geist’s task – developed across world history – to refine and complete its awareness of its own freedom, and its awareness of itself. The more this process of refinement progressed, the more abstract and conceptual it became. In the historical period that Hegel roughly identified with Ancient Greece, this self-awareness could find perfect embodiment in ‘classical art’. In Hegel’s words, art could achieve a ‘free and adequate embodiment of the Idea in the shape’.

However, as this self-awareness became more complex and abstract, it developed beyond art’s capacities for expression. Consequently, art could no longer push forwards the development of Geist. This task fell to the more discursive and conceptually complex spheres of religion and philosophy (the most adequate expression occurring in – to the surprise of no one – Hegel’s own philosophy!). Art, as a means of eliciting progress in the task of articulating Geist and its self-consciousness, became superseded, and no longer of use in this task.

Hegel’s idea of history as having a kind of narrative structure, a movement in stages towards a goal, is likely less compelling to us than it was to those of his contemporaries who claimed to understand it. But the idea that art is perhaps best understood as a practice exhibiting a narrative survives as a genuinely interesting idea, and we can make use of it without having to employ Hegel’s more obscure thoughts about history and Geist.

Danto gave just this kind of account: an explanation of the end of art that, though inspired by Hegel, was not founded on his notions of world history and Geist, and was focused on the recent history of art. Danto’s claim was that art’s first task – the first narrative it worked through – was the perfection of verisimilitude; of producing images that presented an exact likeness of their objects. From the painstaking work in Greek sculpture, aided by advances in Greek anatomy (the sculptures Doryphoros, or Myron’s Discobolus, for example), to the progressive use and refinement of optics and the science of perspective in the Renaissance (for example, Masaccio’s use of one-point linear perspective in his Holy Trinity), artists continually improved their ability to depict objects in a lifelike fashion.

These advancements were binding on those who came after – for example, Masaccio’s work with Brunelleschi’s advances in understanding perspective set the tone for the painters who followed, who took up and improved these techniques and generated their own skills and technologies. The camera obscura was later a key technological advancement, in allowing rudimentary reference photographs to be taken (or so the artist David Hockney claims, with growing agreement, based on features of paintings such as Vermeer’s The Music Lesson).

The camera obscura, of course, soon became the photographic camera, which could record virtually perfect likenesses of objects. Art’s innermost goal – its narrative of perfecting representations of objects – had been usurped. It now fell to art, in Danto’s view, to focus on a new question: ‘What is art?’

Much of what followed in the history of art can be arranged into a neat sequence, on Danto’s account. Art found its former narrative completed, and then embarked on a new one: it now set itself the new task of enquiring into what art itself could be, and what the limits of art-hood were. The outer limits of the ability of visual art to be representation – to embody, and elicit an impression of something outside of the artwork, whether it be an object, a sensation, an experience, or a concept – started to be explored. And we can see the fruits of this approach in the various modern schools and ‘isms’ (Cubism, Fauvism, Futurism, and so on) and in works such as Pablo Picasso’s The Aficionado (1912) and Wassily Kandinsky’s Bustling Aquarelle (1923). But one cannot push at limits endlessly without eventually making them senseless; by 1953, Robert Rauschenberg was exhibiting a painting by Willem de Kooning that he had completely erased; it was a blank canvas, with (comparatively) little intrinsic visual value – an artistic hint, in my view, that this new narrative was coming to a natural end.

The world of perfect verisimilitude had morphed into the innovative and unusual approaches of the schools and movements that asked what art was, before finally being wiped away altogether in Rauschenberg’s symbolic erasure of another artist’s work. We can see why Danto might find a second narrative, here – an investigation of the limits, and meaning, of art itself. Underpinning the schools and ‘isms’ of modern visual art was a central push to arrive at an understanding of art’s essence – of what it means for an object to be an artwork. And it was Warhol’s Brillo Boxes that alerted Danto to the recent completion of this second narrative.

In Danto’s view, Warhol’s Brillo Boxes were deeply important because they were visually indistinguishable from non-artworks. There was nothing about the way that they looked that explained what made them artworks, as opposed to containers for scouring pads. Art had pursued the question of how to define itself as far as it could go through the way artworks looked; it now required concepts – art theory – to carry forward this task, as the objects alone were no longer up to this task unaided. Just as art had handed over the pursuit of verisimilitude to the camera, so now its search for self-definition had reached the point where it needed to pass on its task to art theory. So, art’s second and final narrative has been completed.

Hegel and Danto believed that art ends under very specific conditions. Their work asks us to see art as having a narrative and a goal; a desired outcome that we can recognise that artists together are working towards to achieve. When we can see no advance in the realisation of this goal, in Hegel and Danto’s view it seems reasonable to argue that art has ended, and no further progress is possible.

Hegel constructed his narrative for art against the backdrop of notions that we might now find hard to accept; on the other hand, Danto showed us that careful study of the history of art made the idea of art having an internal narrative appealing, and fitted the evidence of art history well. If art has a narrative, and a goal, it stands to reason it might one day achieve that goal, and complete its narrative: that it might come to an end. So, the broad idea of art coming to an end is one we cannot easily write off. But perhaps we should look a little closer at this. Even if we accept that individual narratives can come to an end, why think that there could be an end to all narratives themselves? After all, Danto saw art as replacing its first narrative with a second; why couldn’t there be a third one? Even if we agree with Danto that art has gone as far as it can in investigating what it means to be art, why rule out the possibility that art might embark upon a new narrative and find itself a new goal?

Both Hegel and Danto anticipated the art that came after them, but understood it not as progress in a new direction, but as further symptoms of the end of art. Hegel was writing towards the end of the great outburst of creativity known as German Romanticism. He anticipated an increase in the conceptual content of art, a move beyond sensuous art into something radically different. This (incompletely) described many of the features of the great art movements that came after him, which moved away from depicting the world, or conceptual ideas, with complete adequacy, and instead reflected on the very limits of artistic expression itself. Cubism, for example, no longer perfected perspective, or wanted to, but instead interrogated it, and attempted to show us the very limits of the way an artwork might represent something. This can be seen especially in the ‘analytical’ phase of Cubism – for example, in Picasso’s Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1910).

Danto, similarly, was writing at the very tail-end of modernism, and the beginning of what came to be known by many as post-modernism. Danto’s enthusiastic description of the end of art, as he himself realised, captures the essence of what some call art’s post-modern era (though Danto preferred to term it the ‘post-historical’ era). Both Hegel and Danto recognised the clear artistic trends confronting art at their time, and with remarkable foresight predicted, and even influenced, those forms of art that would soon emerge. But both philosophers described this inevitable ‘following after’ as not so much the beginning of a new narrative, but rather the end of all narrative. For both Hegel and Danto, the end of art that each pinpointed was supposed to be followed by the opening up of an endless and unstructured chronicle.

Perhaps each of these philosophers was wedded to an idea of art – of what counts as art; and of what art should do – that no longer applied. Perhaps art keeps ending for philosophers such as Hegel and Danto just because they confuse art, as a changeable, endlessly perfectible practice, with their historically contextualised conceptions of what art must be. All of us are prone to this misplaced essentialism about art. Influenced by the culture and arguments we have been reared within, we insist that art must necessarily be engaged in this set of questions – our set of questions – and lose any sense of progress once these questions are resolved, or found to be dead ends and no longer relevant. When art takes on a different shape, as it did in Hegel’s time, and in Danto’s, we are then prone to understand this to be the final symptom of art’s coming to rest – the end of a final narrative. In fact, this tells us only that our starting principles were more about our own time and culture than we had guessed, and that art resists being summed up in any neat single narrative, and always contains a great many overlapping narratives of its own.

This would be a wonderfully neat and open-handed response to the problem; but is it right?

Hegel and Danto’s discussions of the end of art are clearly Euro- and US-centric – as is this essay. Within these constraints, if we want to resist Hegel and Danto’s conclusions about the end of art – and if we believe that art can still progress and develop – we need to identify some new narrative and goal by which art could now be structured. Can we discern some future form of artistic goal that might emerge, or already be emerging, and once more bind together the free-floating strands of artistic creation into a unified practice with a clear goal? I don’t think we can; at least not yet. This might tell us that some kind of end of art has indeed occurred. Or it might be that we are merely waiting for art’s next narrative, when the goals and aims of art will change yet again in ways we cannot predict.

By Owen Hulatt -- teaching fellow in philosophy at the University of York. His research focuses on profundity in music and art. His latest book is Adorno’s Theory of Aesthetic and Philosophical Truth: Texture and Performance. Article published @ Aeon https://goo.gl/f18BxV

0 notes