#raymond spruance

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This Day in History: The Battle of Tinian

On this day in 1944, United States Marines invade the island of Tinian, in the Pacific. By August 1, they would be in possession of the island. “In my opinion,” Admiral Raymond A. Spruance would say, “the Tinian operation was probably the most brilliantly conceived and executed amphibious operation in World War II.”

It would prove vitally important, too. Tinian later became the base of operations for aircraft dropping nuclear bombs on Japan. Its relatively flat terrain made it the perfect spot for airfields.

It would all start with a surprise attack.

The story continues here: https://www.taraross.com/post/tdih-wwii-tinian

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film Review - Midway (2019)

Our next film review sticks with narratives based on real-world events, but compared to the last one, we’re going back a few years and west by a great many miles, as we check out the 2019 film Midway…

Plot (as adapted from Wikipedia):

In December 1937, Lieutenant Commander Edwin T. Layton, an American naval attaché intelligence officer, is warned during a state function by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto that, because 80% of Japan's oil is imported, if the US were to threaten their oil supply, then the Japanese would have no choice but to wage war.

On December 7, 1941, during World War II, following the US's decision to cut off Japan's oil supply, the Japanese launch a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, forcing the US to enter the war. In response, naval aviator Lieutenant Richard "Dick" Best and the Air Group of the carrier USS Enterprise try to find the Japanese carrier fleet, but they are unsuccessful.

Admiral Yamamoto, with the support of Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, proposes an audacious plan to invade Midway Island using the four available Japanese carriers known as the "Kido Butai", but the Japanese Army overrules them. In February 1942, the USS Enterprise launches raids against the Marshall Islands. In April, after Lieutenant Colonel Doolittle's raid on Tokyo, Yamamoto, Yamaguchi, and Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo are permitted to carry out their plan to attack Midway.

In May, following the Battle of the Coral Sea, Layton, along with Joseph Rochefort and his cryptography team, use signals intelligence to intercept Japanese messages about an operation against an objective identified only as "AF". Layton and his team believe that "AF" is Midway Atoll, while Washington believes it to be a target in the South Pacific. Still, the newly appointed commander-in-chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, remains sceptical. To prove their theory, Layton instructs Midway to send an unencrypted message stating they are suffering from a water shortage. The Japanese pick up this signal and send an intercepted message about water shortages on "AF," confirming that "AF" is indeed Midway.

Hoping to mount his surprise attack, Nimitz orders the aircraft carriers USS Hornet and Enterprise to be recalled from the Coral Sea and demands that the damaged USS Yorktown be repaired in 72 hours for combat operations. Halsey is placed on shore leave due to shingles and is temporarily replaced by Admiral Raymond A. Spruance.

On June 4, the Japanese launch an air attack on Midway. Initial attempts by US land-based aircraft to strike the Japanese fleet carriers fail. However, Nagumo is shaken when a crashing American bomber narrowly misses the bridge of the Japanese aircraft carrier Akagi in what may have been a ramming attempt. The submarine USS Nautilus tries to attack the Japanese fleet but is chased off by the Japanese destroyer Arashi. American squadrons attack the Japanese fleet without much luck, though the attacks prevent the fleet from launching their counterstrike. Upon spotting the Arashi from the air, Wade McCluskey correctly infers the Japanese destroyer is rushing back to the main Japanese fleet and leads his planes to follow its course. Arriving to find the Japanese Combat Air Patrol at low level due to the previous attacks, the dive bombers score several hits on the Japanese aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga and Sōryū, resulting in fires and further explosions, crippling all three. The shell-shocked Nagumo is persuaded to transfer his flag. Yamaguchi, aboard the sole remaining intact carrier, Hiryu, launches a strike that succeeds in crippling Yorktown, prompting Enterprise and Hornet to launch their remaining aircraft in response. Best leads the squadron, which successfully inflicts heavy damage to the Hiryu. Admiral Yamaguchi chooses to go down with his command along with Captain Kaku, as Hiryu is scuttled.

Yamamoto orders a general withdrawal. At Pearl Harbor, Rochefort intercepts the Japanese order to withdraw and passes it to Layton, who then informs Nimitz. Best is discharged from the Navy for his lung problems, incurred due to the use of faulty breathing apparatus during the attack, and returns home to his wife and daughter.

Review:

When I reviewed the Michael Bay film Pearl Harbour for my Facebook run of reviews, just over a decade ago, I noted that feature films showing war were not meant to be totally historically accurate. That was, and by and large still is, the business of documentary programs and not film dramatizations. However, since I did that review, I’ve seen more war films that strive for historical accuracy as much as possible, and I’ve seen that it often leads to films being better. While mainstream critics have been negative about this film and its profit levels were insufficient to avoid being labelled a box office bomb, there was a conscious effort by those involved to be more accurate, so do the critics have it wrong?

To my mind, the answer is that yes, the critics are wrong. The US film-rating site Rotten Tomatoes, for example, apparently claimed this film was re-telling a well-known story, which is typical of American bias regarding their own history. After all, one country’s well-known historical event is very often unknown history to the wider world, especially if that moment is seen in a negative light by other nations. History, after all, is often taught selectively, with many nations using their “best moments”, teaching history like a highlights reel, so it’s good that Midway takes a more balanced approach in how it depicts its events. So, for those of us not from America, this film represents a chance to learn a part of history we don’t know, albeit through the dramatic distortion of Hollywood.

Unlike Pearl Harbour, Midway isn’t making up a story around real events, but tells that story with tweaks here and there to work without the story-telling medium being used. It’s also probably more accurate than the 1970’s Midway film due to a book written by the real Lt. Comm. Layton coming out in 1985 that better details the issues around intelligence that contributed to the various engagements we see in the film. As such, while some might be claiming this latest film is less original, I would argue it is actually more original because it’s trying to get across a more accurate representation than the other two films while still being a dramatic re-telling and not a flat, dry documentary.

Helming the project is Roland Emmerich, known for such films as Independence Day, The Day After Tomorrow, 2012 and White House Down. As this brief snippet of his filmography shows, he puts together good films, and that’s reflected in the choice of cast, all of whom play their roles wonderfully. Among those playing the multitude of historical characters in the film are Ed Skrien (Deadpool), Luke Evans (Beauty and the Beast 2017 live-action remake), Woody Harelson, Patrick Wilson (The A-Team film, Aquaman, Watchmen), Aaron Eckhart (The Dark Knight), Denis Quaid, Joe Jonas and Mandy Moore.

Now the last one might catch some by surprise, myself included. Being a teenager during the late 90’s and early 2000’s, I originally knew Mandy Moore as a brief-lived singer following the template set by Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera. However, based on her Wikipedia page, it appears that Moore has alternated between singing and acting for much of her career. Indeed, she also has a claim to Disney fame due to providing the voice of Rapunzel in Disney’s Tangled. In this film, she plays the wife of Ed Skrien’s character, and does a superb job, much as the rest of the cast does.

If I was to criticise this film on any count, it would be over its depiction of why Japan attacked the United States. Both in Pearl Harbour and now in this film, Japan’s reasons are limited to an issue with their oil supply, but this is a major simplification, perhaps clung to by the United States and its film industry because of the nation’s past with getting into conflicts over oil subsequent to World War II. Had the film taken a little extra time to be a bit more nuanced, it might have been the closest we could come to historical accuracy in a film covering these events. As it is, maybe someone neutral to both the US and Japan could do an historically accurate political drama showing the build-up to Pearl Harbour from a neutral perspective. Otherwise, I’d say this film rates a score of 9 out of 10.

0 notes

Text

The damage control parties of USS RANDOLPH (CV-15) fight the fire in the overhead hangar and aft flight deck from a kamikaze attack. Later, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance and Capt Baker inspect damage to ship as crewmen are busily repairing the ship.

Filmed on March 11, 1945.

NARA: 23643

#USS Randolph (CV-15)#USS Randolph#Essex Class#Aircraft Carrier#Kamikaze#March#1945#world war 2#world war ii#WWII#WW2#wwii history#history#military history#military#united states navy#us navy#navy#usn#u.s. navy#video#war#my post

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

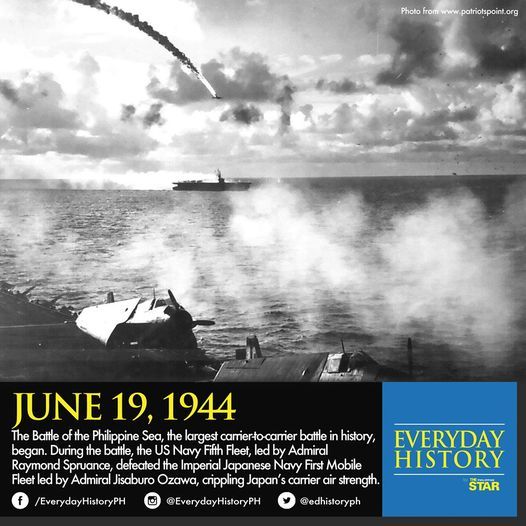

Everyday History: On this day in 1944, the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the largest carrier-to-carrier battle in history, began. During the battle, the US Navy Fifth Fleet, led by Adm. Raymond Spruance, faced the Imperial Japanese Navy First Mobile Fleet, led by Adm. Jisaburo Ozawa. The aerial phase of the battle was also known as the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot because of the significant losses the US inflicted on Japan’s carrier air strength. It was the last of the major carrier-to-carrier engagements between American and Japanese naval forces in World War II.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

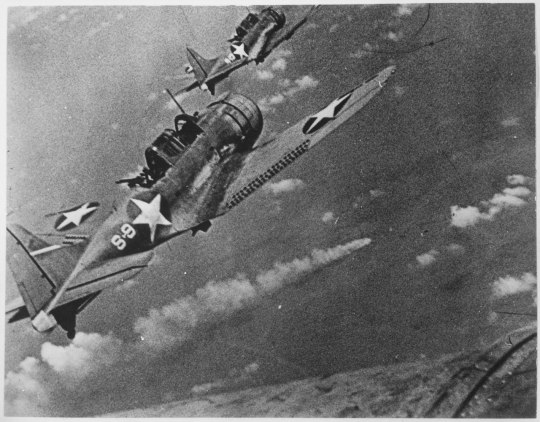

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea.[6][7][8] The U.S. Navy under Admirals Chester W. Nimitz, Frank J. Fletcher, and Raymond A. Spruance defeated an attacking fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy under Admirals Isoroku Yamamoto, Chūichi Nagumo, and Nobutake Kondō near Midway Atoll, inflicting devastating damage on the Japanese fleet. Military historian John Keegan called it "the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare",[9] while naval historian Craig Symonds called it "one of the most consequential naval engagements in world history, ranking alongside Salamis, Trafalgar, and Tsushima Strait, as both tactically decisive and strategically influential".[10]

Luring the American aircraft carriers into a trap and occupying Midway was part of an overall "barrier" strategy to extend Japan's defensive perimeter, in response to the Doolittle air raid on Tokyo. This operation was also considered preparatory for further attacks against Fiji, Samoa, and Hawaii itself. The plan was undermined by faulty Japanese assumptions of the American reaction and poor initial dispositions. Most significantly, American cryptographers were able to determine the date and location of the planned attack, enabling the forewarned U.S. Navy to prepare its own ambush.

Four Japanese and three American aircraft carriers participated in the battle. The four Japanese fleet carriers—Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, and Hiryū, part of the six-carrier force that had attacked Pearl Harbor six months earlier—were sunk, as was the heavy cruiser Mikuma. The U.S. lost the carrier Yorktown and the destroyer Hammann, while the carriers USS Enterprise and USS Hornet survived the battle fully intact.

After Midway and the exhausting attrition of the Solomon Islands campaign, Japan's capacity to replace its losses in materiel (particularly aircraft carriers) and men (especially well-trained pilots and maintenance crewmen) rapidly became insufficient to cope with mounting casualties, while the United States' massive industrial and training capabilities made losses far easier to replace. The Battle of Midway, along with the Guadalcanal campaign, is widely considered a turning point in the Pacific War.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Midway

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Balao-class submarine, USS Lionfish was laid down on 15 December 1942, launched on 7 November 1943, and commissioned on 1 November 1944. Her first captain was Lcdr. Edward D. Spruance, son of the famous World War II admiral, Raymond Spruance.

After completing her shakedown cruise off of New England, she headed to the Pacific and commenced her first war patrol in Japanese waters on 1 April 1945. Ten days later, she dodged two torpedoes fired at her by a Japanese submarine and on 1 May destroyed a Japanese schooner with her deck guns. After a rendezvous with the submarine Ray, she transported B-29 survivors to Saipan and then made her way to Midway Island for replenishment.

On 2 June she started her second war patrol, and on 10 July she fired torpedoes at a surfaced Japanese submarine, after which Lionfish’s crew heard explosions and observed smoke through their periscope. She subsequently fired on two more Japanese submarines and ended her second and last war patrol performing lifeguard duty (the rescue of downed fliers) off the coast of Japan. When hostilities ended on 15 August she headed for San Francisco and was decommissioned at Mare Island Navy Yard on 16 January 1946.

Lionfish was recommissioned on 31 January 1951, and headed for the East Coast for training cruises. After participating in NATO exercises and a Mediterranean cruise, she returned to the East Coast and was decommissioned at the Boston Navy Yard on 15 December 1953.

In 1960, the venerable submarine was called to duty again, this time serving as a reserve training submarine at Providence, Rhode Island. In 1971, she was stricken from the Navy Register, and in 1973, she was unveiled for permanent display as a memorial at Battleship Cove, where she has evolved into one of the museum’s most popular exhibits and a revered monument to all submariners.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Change of Command Ceremony for Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz on board USS Menhaden (SS-377). In a change of command ceremony, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, USN, is relieved as Commander-in-Chief Pacific-Pacific Ocean Area (CINCPAC-CINCPOA) by Admiral Raymond A. Spruance on board USS MENHADEN (SS-377) moored at Submarine Base, Pearl Harbor, 24 November 1945. On left side of pier is USS Dentuda (SS-335), and passing by is USS Begor (APD-127).”

(NHHC: NH 62277)

#Military#History#USS Menhaden#Submarine#USS Dentuda#USS Begor#Transport#United States Navy#US Navy#WWII#WW2#Pacific War#World War II

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle group spruance

Spruance entered her first major overhaul in 1980 at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard. Upon "breaking" (unfurling) the flag on the halyards, they would play the theme song from the 1976 film Rocky as they increased speed and sailed ahead of the logistics vessel. fleet, had an underway replenishment breakaway flag (flown while pulling away from receiving supplies and fuel from a logistics ship at sea) that was a replication of the large yellow warning seen on the side of aircraft carriers, with red block letters saying "BEWARE JET BLAST" on a large yellow background. Spruance, being the first gas-turbine powered ship in the U.S. Spruance suffered a malfunction in one of her LM2500 Gas Turbine Main Engines and had to replace the engine while deployed. During this deployment, Spruance made a transit into the Black Sea to conduct surveillance on the new Soviet helicopter carrier, Moskva, as she steamed from her building shipyard to the Soviet Red Banner Northern Fleet. The other warships in this task force included USS Biddle, USS Conyngham, USS Milwaukee, and USS Mount Baker. Spruance 's first operational deployment was in October 1979 to the Mediterranean Sea, as a member of the USS Saratoga Carrier Battle Group. Also added to Spruance after several years of service was an eight-cell launcher for Harpoon antiship missiles. This replaced the original Mark 16 ASROC launcher. Spruance received one Mark 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) during the late 1980s. At first she was armed with two 5-inch naval guns, an ASROC missile launcher, and an eight-cell NATO Sea Sparrow missile launcher. Spruance was the first of a highly-successful class of anti-submarine warfare and anti-ship destroyers, and was the first destroyer powered by gas turbines in the U.S. Eventually, Litton's bid won the competition. Of the $30 million assigned, $28.5 million has been provided to three contractors. ( May 2008) ( Learn how and when to remove this template message)īath Iron Works, General Dynamics and Litton Industries submitted proposals for production of DD-963 on 3 April 1969. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Spruance was decommissioned on 23 March 2005 and then was sunk as a target on 8 December 2006. Atlantic Fleet, assigned to Destroyer Squadron 24 and operating out of Naval Station Mayport, Florida. Spruance was built by the Ingalls Shipbuilding Division of Litton Industries at Pascagoula, Mississippi, and launched by Mrs. USS Spruance (DD-963) was the lead ship of the United States Navy's Spruance class of destroyers and was named after Admiral Raymond A. 1 x 61 cell Mk 41 VLS launcher for Tomahawk missilesĢ x Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk LAMPS III helicopters.2 x Mark 32 triple 12.75 in (324 mm) torpedo tubes ( Mk 46 torpedoes).2 x quadruple Harpoon missile canisters.1 x 8 cell NATO Sea Sparrow Mark 29 missile launcher.2 x 5 in (127 mm) 54 calibre Mark 45 dual purpose guns.AN/SLQ-25 Nixie Torpedo Countermeasures.AN/SQR-19 TACTAS towed array Passive sonar.Mk 23 TAS automatic detection and tracking radar.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

80th anniversary of the #battleofmidway Thank God for Admiral Raymond A. Spruance #NorthAmericaStrong (at Midway) https://www.instagram.com/p/CeaUr25ura0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

https://pacificeagles.net/battle-of-midway-the-torpedo-attack/

Battle of Midway: The Torpedo Attack

Task Force 16 – Enterprise and Hornet, under RAdm Raymond Spruance – sailed for Midway on the 29th of May, just two days after Kido Butai departed from Japan. RAdm Frank Fletcher’s Task Force 17, including the bruised and battered Yorktown, sailed a day later. She was carrying a rebuilt air group, with three former Saratoga squadrons replacing the units worn down by months of combat in the South Pacific. Fletcher was in overall control of the American forces, but throughout the upcoming battle he would give Spruance great latitude to operate independently. Both carrier task forces passed the planned Japanese submarine patrol lines before they were in place, and so were undiscovered as they reached the optimistically name ‘Point Luck’ northeast of Midway. From this location it was hoped that Fletcher could surprise and pounce on the Japanese carriers, expected to approach Midway from the northwest.

Fletcher and Spruance marked time near Midway, conducting light flight operations and waiting for word of the Japanese fleet. That word finally came at 0530 on June 4th, when one of Midway’s patrolling PBYs reported a carrier 180 miles from the island, with a follow-up message at 0552 reporting two carriers in sight. The staffs of both Task forces conferred to work out the best plan of attack. The three American carriers would sail south west to close the distance to the unsuspecting Japanese. Spruance’s Task Force 16 was to attack as soon as practically possible, around 0700, whilst Task Force 17 would conduct searches to the north for the two unreported carriers before also committing strikes against those already reported. The 0700-launch time gave the best chance of hitting the Japanese when they were most vulnerable – Spruance’s Chief of Staff Capt Miles Browning shrewdly calculating that an early launch would catch the Japanese in the act of recovering their aircraft from the Midway strike.

Enters Pearl Harbor, 26 May 1942. She left two days later to take part in the Battle of Midway. Photographed from Ford Island Naval Air Station, with two aircraft towing tractors parked in the center foreground.

Each of the carrier air groups launched their strike using different tactics in terms of coordination between their constituent squadrons. The Hornet Air Group, under the direction of Capt. Marc A. Mitscher, assigned all 10 of its VF-8 F4F Wildcats to escort the VB-8 and VS-8 SBDs, whilst VT-8 went in alone. The Enterprise Air Group also elected to keep VF-6’s Wildcats at altitude to cover VB-6 and VS-6, but VT-6 could at least call down support if required from the fighters. Only the Yorktown Air Group, realising how vulnerable the torpedo bombers were, provided direct support for the lumbering TBDs – albeit just 6 F4Fs. All three carriers kept a healthy reserve of fighters to protect the two Task Forces. Yet again, the Americans were hampered by a shortage of fighters that forced commanders to choose between supporting strikes or protecting their ships.

In any case, the group rendezvous became a mess – VF-6 failed to find VB-6 and VS-6, instead elected to fly very high cover over what they thought were VT-6s TBDs, with who they had no radio contact. The Hornet Air Group was tardy in launching, and then set out on completely the wrong heading for the Japanese fleet, all except for VT-8. Cdr John C. Waldron’s squadron alone chose to take a course which unerringly took them directly to Kido Butai. Unwittingly, VF-6 was actually escorting Waldron, having mistake his squadron for VT-6. Only the Yorktown Air Group, which launched her strike an hour after the others when no further news of further carrier sightings was evident, managed a well-coordinated running rendezvous.

The Hornet Air Group, less Torpedo Eight, suffered terrible losses without sighting even a single Japanese ship. Under the leadership of Cdr Stanhope C. Ring, 37 SBDs and 10 F4Fs droned west for hours, passing far to the north of Kido Butai. Gradually the shorter-ranged F4Fs began to run low and fuel and in pairs, then in divisions, they turned back, leaving the SBDs alone. None of the fighters would manage to find the Hornet, with all of the forced to ditch far out at sea. Two of the pilots were never seen again, the remaining eight picked up gradually over the ensuing days by patrol planes, many suffering from exposure or sunburn. The SBDs of VB-8, loaded with heavy 1,000lb bombs, turned back soon afterwards. Cognisant of their poor fuel situation they elected to fly to Midway rather than back to their carrier, jettisoning their bombs just outside the reef – a gesture that was treated as hostile by the jumpy Marine gunners, resulting in damage to several SBDs before they safely landed. Only VS-8, accompanied by Ring, managed to successfully find their way back to base, none the worse for their futile efforts.

Torpedo Eight Attacks

VT-8 was the first to find the enemy. LtCdr Waldron had disobeyed orders to fly due west towards what Hornet’s staff had assumed was the location of the Japanese carriers, and instead had turned to a more southerly course. He found the enemy at 0918, the first of the American carrier squadrons to sight Kido Butai. Waldron tried to get of a radio message informing Spruance of the location of the enemy carriers, but none was ever received. Nevertheless Waldron commenced an attack run that would lead his men into the pages of history.

Seeing three carriers before him, Waldron initially took his men toward Akagi but withering anti-aircraft fire and the arrival of an estimated 35 Zeros led him to choose another flattop, most likely the Soryu. It mattered little – one by one, the gallant crews of VT-8 perished as their slow, obsolete TBDs were shot down into the sea by clouds of enemy fighters. Waldron himself was last seen with his aircraft on fire, both wingmen already lost. He stepped out of the cockpit but did not have time to release his parachute before his TBD crashed. Only Lt George Gay’s aircraft survived long enough to release its torpedo, but he too was shot down without seeing the results of his drop. Gay survived the crash and escaped from his sinking aircraft, but his rear gunner perished. That left Gay as the sole survivor of his squadron – 15 TBDs had been shot down, carrying 29 men to their deaths. High above, Lt James Gray’s VF-6 watched the TBDs go in but never heard any calls for help. After orbiting uselessly for 30 minutes the fighters turned for home without firing a shot.

Torpedo Six

Then came Enterprise’s VT-6 – fourteen TBDs under LtCdr Eugene E. Lindsey. Lindsey had been painfully injured in a crash a few days before the battle that had left him with broken ribs and a strained back, but he refused to let his men fly into battle without him. Despite taking off from the Enterprise slightly earlier than Hornet’s VT-8, Lindsey’s men took a more circuitous route to find the enemy and ended up lopping around to attack from a different direction, about half an hour after Waldron had begun his attack.

Arriving from the southwest, Lindsey split his bombers into two groups of seven, leading the first division himself whilst the second division was led by Lt Arthur V. Ely. Lindsey hoped to be able to deliver an ‘anvil’ attack against one of the Japanese carriers and singled out the Kaga as the object of the attack. The Japanese carriers spotted the newcomers whilst they were still some distance off, and turned away from the incoming Americans. This meant that the 110-knot TBDs were trying to overhaul the 30-knot carriers – it took an agonisingly long time before attack position was reached. All the while VT-6 was exposed to anti-aircraft fire from Kido Butai and the unwanted attentions of the same Zeroes that had annihilated VT-8.

Ten of the Devastators were shot down before they reached position to release their Mark 13s, including the aircraft of LtCdr Lindsey – none of the crew survived. Ely frantically radioed for help from VF-6, who he assumed were still at high altitude, but Gray’s fighters never heard the call. Eventually the survivors reached attack position and five torpedoes were dropped against the Kaga, but again none of the American fish hit home. One TBD appeared to explode when its torpedo was hit by fire from a Zero, whilst the crew of another was forced to make a water landing because of fuel leak caused by battle damage, the two crewmen spending 17 days adrift before they were sighted by a PBY and picked up. Only four TBDs returned to Enterprise, one of them so badly damaged it had to be pushed over the side.

A Douglas TBD-1 Devastator torpedo plane, carrying a Mk. XIII torpedo, en route to attack the Japanese carrier force during the morning of 4 June 1942.

Torpedo Three

The next squadron to arrive, and the last of the three torpedo units, was Yorktown’s VT-3. Unlike the other groups, Yorktown’s flyers had managed to rendezvous successfully and LtCdr Lance E. Massey’s TBDs had an escort of six F4Fs from VF-3, and high above 17 Dauntless bombers of VB-3 waited to make an attack coordinated with the torpedo planes. The fighter escort did little good, as LtCdr John S. Thach’s men had to fight for their lives and could not offer any protection to the vulnerable TBDs – one Wildcat was shot down and another forced to break off with damage, the survivors using Thach’s innovative ‘beam defense’ manoeuvre to defend each other. Unfortunately this left Massey’s men exposed to the attentions of the relentless Zeros.

The twelve Devastators bored in towards the Hiryu, with five TBDs under Chief Wilhelm G. Esders reaching attack position unhindered. All of the Mark 13s they released failed to hit the carrier, passing ahead and astern of her. Three of Esders’ Devastators were shot down soon afterwards. The other TBDs, including that of Massey, never got the chance to attack as the Zeros picked them off one by one, leaving no other survivors. Massey himself was one of the first to fall, his aircraft falling victim to a Japanese fighter. In total ten of VT-3’s Devastators were lost, to add to the 25 from VT-6 and VT-8 that failed to return. Not a single torpedo found it mark.

The loss of 35 TBDs during the attacks was final proof of the complete obsolescence of the aircraft, Facing the cream of the Japanese naval air arm, the venerable old Devastator – slow, unwieldy, and carrying a torpedo that was unreliable at best – had been shown to be totally inadequate in modern war, and many fine crews had paid for this fact with their lives. They had all fallen without managing to inflict any damage on the enemy, but they had served to distract anti-aircraft crews and the Zero pilots, drawing their attention away from other American units which would soon deliver a telling blow. Whilst the TBDs of VT-3 were fighting and dying, high above three squadrons of SBD Dauntless dive bombers had moved into position, completely undetected, and would soon turn the battle decisively in favour of the Americans.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This Day in History: Battle of Tinian

On this day in 1944, United States Marines take possession of the island of Tinian, in the Pacific. They’d invaded the island just eight days earlier. “In my opinion,” Admiral Raymond A. Spruance would say, “the Tinian operation was probably the most brilliantly conceived and executed amphibious operation in World War II.”

It would prove vitally important, too. Tinian later became the base of operations for aircraft dropping nuclear bombs on Japan. Its relatively flat terrain made it the perfect spot for airfields.

It would all start with a surprise attack.

The Japanese were expecting Americans to hit Tinian so they had heavily fortified the beaches near Tinian Town. Much of the island was rimmed by cliffs, but the area near Tinian Town had better beaches. Another similar beach at Asiga Bay was also heavily fortified, but two smaller beaches to the northwest weren’t as well defended.

Those beaches were narrow, and it would take a great deal of planning and organization to get troops and equipment ashore efficiently, without clogging beaches.

Naturally, our Marines were up to the task.

The story continues at the link in the comments.

#tdih#otd#this day in history#history#history blog#world war ii#wwii#US Marine Corps#us marines#sharethehistory

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Admirals Chester W. Nimitz, Ernest J. King, and Raymond Spruance aboard the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis, ca. 1944. I’ve been reading about these three men lately. King (center) played a key role in advising President Roosevelt during the war. He can be credited with focusing American men and material toward the Pacific early in the war, rather than the “Europe First” that was the knee jerk reaction after she entered the war. Additionally, he held out for Nimitz’ command of naval forces in the Pacific. I find it interesting that America could afford to place two offensive groups in theater, one with the Army under MacArthur and the other under Nimitz with the Navy.

Spruance was recommended by Halsey as his replacement when Halsey had a shingles breakout right before the Midway Operation. He served as Nimitz’ Chief of Staff after the battle, overseeing operations against the Marshalls and Iwo Jima from the Indianapolis (above) or the Battleship New Jersey. Spruance and Halsey would work together effectively for the remainder of the war.

I’ve read some of Nimitz letters home after assuming command at Pearl Harbor and they really show a man intent on doing his duty and following the instructions of his leaders. He was really fascinating!

Chester Nimitz (24 Feb. 1885 - 20 Feb. 1966) Naval Academy Class of 1905.

Ernest King (23 Nov. 1878 - 25 June 1956) Naval Academy Class of 1901.

Raymond Spruance (3 July 1886 - 13 Dec. 1969) Nav. Academy 1906.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Admirals William Halsey and Raymond Spruance aboard USS New Mexico, 27 May 1945

0 notes

Quote

When reconsidering the debacle that befell on the Allied forces in the Netherlands East Indies in early 1942, it is hard not to feel as if one is viewing a colossal tragedy that no Western military commanders might have eluded, let alone overcome. There one must concede that ABDAFLOAT’s limited naval forces would have produced no better results in the final analysis, whether commanded by Bill Halsey, Raymond Spruance, Frank Jack Fletcher, James Somerville, or Andrew Cunningham.

In The Highest Degree Tragic, by Donald M. Kehn

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“In a change of command ceremony, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, USN, is relieved as Commander-in-Chief Pacific-Pacific Ocean Area (CINCPAC-CINCPOA) by Admiral Raymond A. Spruance on board USS Menhaden (SS-377) moored at Submarine Base, Pearl Harbor, 24 November 1945. Shown here boarding the submarine is Fleet Admiral Nimitz followed by Admiral Spruance. the sub on opposite side of pier is USS Dentuda (SS-335).”

(NHHC: NH 62274)

44 notes

·

View notes

Link

The United States was formed through rebellion against the British empire, but well after the Revolutionary War ended in 1783, resistance to that empire continued to shape America’s history. The civil rights movement, for instance, was not only deeply influenced by the thought and practices of the Indian anticolonial movement, but it was also part of a wider antiracist struggle in the era of decolonization that connected activists across Asia, Africa and beyond, mobilizing the global diasporas of Asians and Africans that colonialism had created.

Those diasporas extended to the United States. The British shipped enslaved Africans to the Americas starting in the 17th century. Indians were also in the United States from the start, such as the Bengali woman Mary Emmons, who was Aaron Burr’s servant and mother of two of his children. More Indians, many of them refugees from colonialism, arrived from the 19th century.

And so, freedom struggles abroad merged with the struggles of people of color in the United States. If Martin Luther King Jr. was inspired by Mohandas K. Gandhi, Indian anticolonial activists in the United States, like Lala Lajpat Rai, found inspiration in the Black struggle there from the early 20th century.

These intertwined histories of displacement and struggle have profoundly affected America’s current political moment. Two of the most powerful politicians in the Democratic Party, Barack Obama and Kamala Harris, are the product of families shaped by the global anticolonial and antiracial optimism of the 1960s, by the bonds of progressive young people around the globe who attempted to make new kinds of societies at a moment in which empire seemed to be completing the process of disintegration that had begun in 1776. As Kamala Harris vies for the Vice Presidency, a complete recounting of her formation requires recognizing her as both a quintessentially American politician—because of, not despite, her being a child of immigrants—and part of a global story of the former British empire.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

For Obama, that story goes back to colonial Kenya. His grandfather, serving with British regiments there, saw much of the British empire, including South Asia, during World War II. In the 1950s, he was detained for six traumatic months in the brutal camps the British established to crush anticolonial rebellion in Kenya. His son, the senior Barack, was arrested and jailed for his anticolonial involvement at the age of 20, before coming to the U.S. for university in 1959, on the eve of Kenya’s independence, to study economics. Economics, specifically development economics, was the discipline of the decade for the leaders of the emerging “Third World.” Questioning the theoretical assumptions that had justified colonialism, they strove to remake the discipline for the postcolonial era. With its technical power, they hoped to unleash the progress that colonialism had stifled in their nations.

President Obama’s moving memoir Dreams From My Father recounts his visit to Kenya in 1988, where he realized how profoundly colonialism had shaped his grandfather’s and his father’s lives, including his father’s blind faith in Western technocracy. In fact, the future president concluded, progress depended on “faith in other people.” He saw his work as a community organizer in Chicago as a continuation of his Kenyan forefathers’ struggle for freedom. Equality in America was, to him, part of global anticolonial struggle.

Obama also encountered Indians in Kenya, where, as in many African colonies, they had been brought by the British as indentured workers. When his relatives criticized the community’s seeming disloyalty to Kenya, Obama reassured them with stories of South Asian solidarity with Black struggle in the United States. Alongside the history of Indian anti-Blackness is this history of antiracist solidarity. Thus, after the predominantly white-settler government of another British African colony, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), unilaterally declared independence in 1965, the Indian government deputed P.V. Gopalan to newly independent Zambia (formerly Northern Rhodesia) to help its government cope with the resulting regional refugee crisis.

In 1969, his 5-year-old granddaughter visited him there; that granddaughter was Kamala Harris. In India, Gopalan, like Obama’s grandfather, had begun his career working for the British colonial government. According to his granddaughter, he participated in the Indian freedom struggle and frequently talked to her of the importance of civil rights and equality.

Kamala had come to Zambia with her parents. Her father, Donald Harris, had been born in another British colony, Jamaica, in 1938, a year of massive anticolonial rioting. There, too, people of Indian and African heritage lived together: after slavery ended in the 1830s, the British shipped in Indian indentured labor to work the plantations. A year before Jamaica’s independence in 1962, Donald arrived in the United States aiming for a PhD at U.C. Berkeley—in, again, economics, to foster his newly freed country’s growth. There he met a PhD student in endocrinology, Shyamala Gopalan, through common involvement in the civil rights movement on campus; their daughter Kamala also became part of that history as a young girl bussed to school for desegregation.

The common outlines of these family stories reveal the broader, historical forces that made these two influential figures, Obama and Harris, possible: parents daring to alter their societies in the early ’60s by overturning colonial-era hierarchies. Global history has shaped this national historical moment in which Kamala Harris, a woman of Black and Indian heritage, is the Democratic nominee for Vice President. The dividends of past progressivism continue to be paid out today.

Recognizing the way anticolonial bonds forged in the British empire has have shaped our Democratic Party leadership can combat pernicious falsehoods. Those who ignorantly question the American-ness of Obama’s and Harris’s Blackness must contend with the fact that African-American, Caribbean, African and Asian struggles and experiences have always informed one another. The British empire shaped the birth of the United States, and continued to shape its struggle to fulfill the promise of freedom.

Certainly, Obama and Harris are no radical Leftists, whatever their anticolonial inheritance. And yet, they show us that however Left the Democratic Party is today, it has much to do with the way in which the struggle for equality in the United States has been shaped by allied global struggles. After all, the forces of inequality—capitalism, imperialism, slavery—are themselves global, too.

Historians’ perspectives on how the past informs the present

Priya Satia is Raymond A. Spruance Professor of International History and Professor of History at Stanford University and the author of Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution and the forthcoming Time’s Monster: How History Makes History.

from TIME https://ift.tt/3aIhcnu

0 notes