#propping up capitalist systems is not punk

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

JESSE MCCARTHY Notes on Trap A world where everything is always dripping

https://nplusonemag.com/issue-32/essays/notes-on-trap/ A SOCIAL LIFE STRICTLY ORGANIZED around encounters facilitated by the transactional service economy is almost by definition emotionally vacant. 8.

TRAP IS THE ONLY MUSIC that sounds like what living in contemporary America feels like. It is the soundtrack of the dissocialized subject that neoliberalism made. It is the funeral music that the Reagan revolution deserves.

9.

THE MUSICAL SIGNATURE embedded in trap is that of the marching band. The foundation can be thought of, in fact, as the digital capture and looping of the percussive patterns of the drum line. The hi-hats in double or triple time are distinctly martial, they snap you to attention, locking in a rigid background grid to be filled in with the dominant usually iterated instrumental, sometimes a synth chord, or a flute, a tone parallel that floats over the field. In this it forms a continuum with the deepest roots of black music in America, going back to the colonial era and the Revolutionary War, when black men, typically prohibited from bearing arms, were brought into military ranks as trumpet, fife, and drum players. In the aftermath of the War of 1812, all-black brass bands spread rapidly, especially in cities with large free black populations like New Orleans, Philadelphia, and New York. During the Civil War, marching bands would aid in the recruitment of blacks to the Union. At Port Royal in the Sea Islands, during the Union Army occupation, newly freed slaves immediately took to “drilling” together in the evenings in public squares, men, women, and children mimicking martial exercises while combining them with song and dance — getting in formation. The popularity of marching and drilling was incorporated into black funerary practice, nowhere more impressively than in New Orleans, where figures like Buddy Bolden, Louis Armstrong, and Sidney Bechet would first encounter the sounds of rhythm and trumpet, joy and sorrow going by in the streets of Storyville. This special relationship, including its sub rosa relation to military organization, persists in the enthusiasm of black marching bands, especially in the South, where they are a sonic backdrop of enormous proximate importance to the producers of trap, and to its geographic capital, Atlanta.

10.

But closer to home, Traplanta is saddled with too much of the same racial baggage and class exclusion that criminalizes the music in the eyes and ears of many in power. The same pols who disgrace their districts by failing to advocate for economic equity find themselves more offended by crass lyrical content than the crass conditions that inspire it . Meanwhile, systemic ills continue to fester at will. It’s enough to make you wonder who the real trappers are in this town.

— Rodney Carmichael, “Culture Wars”

The pressure of the proliferation of high-powered weapons, the militarization of everyday life, an obvious and pervasive subtext in trap, is also one of the most obvious transformations of American life at the close of the American century: the death of civilian space.

Trap is social music.

TRAP VIDEOS FOR OBVIOUS reasons continue an extended vamp on the visual grammar developed in the rap videos of the Nineties, a grammar that the whole world has learned to read, or misread, producing a strange Esperanto of gesture and cadence intended to signify the position of blackness. In the “lifestyle” videos, the tropes are familiar, establishing shots captured in drone POV: the pool party, the hotel suite, the club, the glistening surfaces of dream cars, the harem women blazoned, jump cuts set to tight-focus Steadicam, the ubiquitous use of slow motion to render banal actions (pouring a drink, entering a room) allegorical, talismanic, the gothic surrealism of instant gratification.

Like David Walker’s graphic pointers in his Appeal, one of the key punctuation marks of this gestural grammar is the trigger finger, pointing into the camera — through the fourth wall — into the consuming eye. The very motion of the arm and finger are perversely inviting and ejecting. You are put on notice, they say. You can get touched.

A preoccupation with depression, mental health, a confused and terrible desire for dissociation: this is a fundamental sensibility shared by a generation.

Among other things, it’s clear there has never been a music this well suited for the rich and bored. This being a great democracy, everyone gets to pretend they, too, are rich and bored when they’re not working, and even sometimes, discreetly, when they are.

19.

IMAGINE A PEOPLE enthralled, gleefully internalizing the world of pure capital flow, of infinite negative freedom (continuously replenished through frictionless browsing), thrilled at the possibilities (in fact necessity) of self-commodification, the value in the network of one’s body, the harvesting of others. Imagine communities saturated in the vocabulary of cynical postrevolutionary blaxploitation, corporate bourgeois triumphalism, and also the devastation of crack, a schizophrenic cultural script in which black success was projected as the corporate mogul status achieved by Oprah or Jay-Z even as an angst-ridden black middle class propped up on predatory credit loans, gutted by the whims of financial speculation and lack of labor protections, slipped backward into the abyss of the prison archipelago where the majority poor remained. Imagine, then, the colonization of space, time, and most importantly cultural capital by the socially mediated system of images called the internet. Imagine finally a vast supply of cheap guns flooding neighborhoods already struggling to stay alive. What would the music of such a convergence sound like?

TRAP IS A FORM OF soft power that takes the resources of the black underclass (raw talent, charisma, endurance, persistence, improvisation, dexterity, adaptability, beauty) and uses them to change the attitudes, behaviors, and preferences of others, usually by making them admit they desire and admire those same things and will pay good money to share vicariously in even a collateral showering from below.

A SOCIAL LIFE STRICTLY ORGANIZED around encounters facilitated by the transactional service economy is almost by definition emotionally vacant.

The grand years of the Obama masque, the glamor and pageantry of Ebony Camelot, is closed. Les jeux sont faits. The echo of black resistance ringing as a choral reminder to hold out is all that stands between a stunned population and raw power, unmasked, wielding its cold hand over all.

The deep patterns of the funeral drill, the bellicose drill, the celebratory drill overlay each other like a sonic cage, a crackling sound like a long steel mesh ensnaring lives, very young lives, that cry out and insist on being heard, insist on telling their story, even as the way they tell it all but ensures the nation’s continued neglect and fundamental contempt for their condition.

TRAP IS INVESTED in a mode of dirty realism. It is likely the only literature that will capture the structure of feeling of the period in which it was produced, and it is certainly the only American literature of any kind that can truly claim to have a popular following across all races and classes. Points of reference are recyclable but relatable, titillating yet boring, trivial and très chic — much like cable television. Sports, movies, comedy, drugs, Scarface, reality TV, food, trash education, bad housing: the fusion core of endless momentum that radiates out from an efficient capitalist order distributing itself across a crumbling and degraded social fabric, all the while reproducing and even amplifying the underlying class, racial, and sexual tensions that are riven through it.

“When young black males labor in the plantation of misogyny and sexism to produce gangsta rap, white supremacist capitalist patriarchy approves the violence and materially rewards them. Far from being an expression of their “manhood,” it is an expression of their own subjugation and humiliation by more powerful, less visible forces of patriarchal gangsterism. They give voice to the brutal, raw anger and rage against women that it is taboo for “civilized” adult men to speak.”

— bell hooks, Outlaw Culture

THE EMO TRAP OF LIL UZI VERT, his very name threading the needle between the cute, the odd, and the angry, might be thought, given his Green Day–punk styling and soft-suburban patina, to be less invested in the kind of misogynistic baiting so common to trap. But this is not the case. Like the unofficial color-line law that says the main video girl in any rap video must be of a lighter skin tone than the rapper she is fawning over, there is a perverse law by which the more one’s identity is susceptible to accusations of “softness” (i.e., lack of street cred), the more one is inclined to compensate by deliberate hyperbolic assertions of one’s dominance over the other sex.

THE QUIRKY PARTICLES coming out of the cultural supercollider of trap prove the unregulated freedom of that space: that in spite of its ferocious and often contradictory claims, nothing is settled about its direction or meaning. The hard-nosed but unabashedly queer presence of Young M.A; the celebratory alt-feminist crunk of Princess Nokia; the quirky punkish R&B inflection in DeJ Loaf; the Bronx bombshell of Cardi B: to say that they are just occupying the space formerly dominated by the boys doesn’t quite cut it. They are completely changing the coordinates and creating models no one dared to foresee. The rise of the female trap star is no longer in question; an entire wave of talent is coming up fast and the skew that they will bring to the sexual and gender politics of popular culture will scramble and recode the norms of an earlier era in ways that could prove explosive in the context of increasingly desperate reactionary and progressive battles for hearts and minds.

The boys are not quite what they were before, either. Bobby Shmurda’s path to “Hot Nigga,” before landing him in prison, landed him on the charts in no small part because of his dance, his fearless self-embrace, and his self-love breaking out in full view of his entire crew. People sometimes forget that for the latter half of the Nineties and the early Aughts, dancing for a “real one” was a nonstarter. Now crews from every high school across the country compete to make viral videos of gorgeous dance routines to accompany the release of a new single. The old heads who grumble about “mumble rap” may not care for dancing, but the suppression of it as a marker of authentic masculinity was the worst thing about an otherwise great era for black music. Its restoration is one of the few universally positive values currently being regifted to the culture by trap.

(sobre Young Thug) The music critic for the Washington Post writes that “if he lived inside a comic book, his speech balloons would be filled with Jackson Pollock splatters,” which is halfway there (why not Basquiat?). Thugger is more exciting than Pollock, who never wore a garment described by Billboard as “geisha couture meets Mortal Kombat’s Raiden” that started a national conversation. Thugger’s work is edgier, riskier, sans white box; if anything it is closer to Warhol in coloration, pop art without the pretension. It is loved, admired, hated, and feared by people who have never and may never set foot in a museum of “modern art.”

THE PROBLEM OF THE overdetermination of blackness by way of its representation in music — its tar baby–like way of standing in for (and being asked to stand in for) any number of roles that seem incongruous and disingenuous to impose upon it — is the central concern of Dear Angel of Death, by the poet Simone White. Her target is the dominantly male tradition in black literary criticism and its reliance on a mode of self-authorization that passes through a cultivated insider’s knowledge of “the Music,” which is generically meant to encompass all forms of black musical expression, but in practice almost always refers to a canonical set of figures in jazz. It’s clear that she’s right, also clear that it’s a case of emperors with no clothes. It may have been obvious, but no one had the courage to say so. Take these notes on trap, for example: they neatly confirm her thesis, and fare no better under her sharp dissection.

Let’s be clear: White’s larger point stands. Looking to trap music to prepare the groundwork for revolution or any emancipatory project is delusional and, moreover, deaf. If we start from the premise that trap is not any of these things, is quite emphatically (pace J. Cole) the final nail in the coffin of the whole project of “conscious” rap, then the question becomes what is it for, what will it make possible. Not necessarily for good or ill, but in the sense of illumination: What does it allow us to see, or to describe, that we haven’t yet made transparent to our own sense of the coming world? For whatever the case may be, the future shape of mass culture will look and feel more like trap than like anything else we can currently point to. In this sense, White is showing us the way forward. By insisting that we abandon any bullshit promise or pseudopolitics, the project of a force that is seeping into the fabric of our mental and social lives will become more precise, more potent as a sensibility for us to try and communicate to ourselves and to others.

34.

TRAP IS WHAT GIORGIO AGAMBEN calls, in The Use of Bodies, “a form-of-life.” As it’s lived, the form-of-life is first and foremost a psychology, a worldview (viz. Fanon) framed by the inscription of the body in space. Where you come from. It never ceases to amaze how relentlessly black artists — completely unlike white artists, who never seem to come from anywhere in their music — assert with extraordinary specificity where they’re from, where they rep, often down to city, zip code, usually neighborhood, sometimes to the block. Boundedness produces genealogy, the authority of a defined experience. But this experience turns out to be ontology. All these blocks, all these hoods, from Oakland to Brooklyn, from Compton to Broward County, are effectively the same: they are the hood, the gutter, the mud, the trap, the slaughterhouse, the underbucket. Trappers, like rappers before them, give coordinates that tell you where they’re coming from in both senses. I’m from this hood, but all hoods are the hood, and so I speak for all, I speak of ontology — a form-of-life.

the force of our vernacular culture formed under slavery is the connection born principally in music, but also in the Word, in all of its manifold uses, that believes in its own power. That self-authorizes and liberates from within. This excessive and exceptional relation is misunderstood, often intentionally. Black culture isn’t “magic” because of some deistic proximity of black people to the universe. Slavers had their cargo dance on deck to keep them limber for the auction block. The magic was born out of a unique historical and material experience in world history, one that no other group of people underwent and survived for so long and in such intimate proximity to the main engines of modernity.

One result of this is that black Americans believe in the power of music, a music without and before instruments, let alone opera houses, music that lives in the kinship of voice with voice, the holler that will raise the dead, the power of the Word, in a way that many other people by and large no longer do — or only when it is confined to the strictly religious realm. Classical European music retained its greatness as long as it retained its connection to the sacred. Now that it’s gone, all that’s left is glassy prettiness; a Bach isn’t possible.

The people who make music out of this form-of-life are the last ones in America to care for tragic art. Next to the black American underclass, the vast majority of contemporary art carries on as sentimental drivel, middlebrow fantasy television, investment baubles for plutocrats, a game of drones.

Coda: What is the ultimate trap statement?

Gucci Mane: “I’m a trappa slash rappa but a full-time G

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get Political (part one)

Contemporary theatre would like to be political: ever since Brecht placed his talents at the service of Marxism – becoming the pride of the post-war East German communist state – and Boal claimed that ‘all theatre is political’, playwrights and directors have grappled with the potential of performance to provide political positions.

Given the intensity of current parliamentary shenanigans, from David Cameron’s destabilising government through a series of referenda, the bold attacks on the welfare state by a Conservative cabinet that barely has public support through a Labour party riven by internal anxiety, despite the popularity of its leader Jeremy Corbyn (who has his own Blue Peter style annual, now available at half-price in Waterstones), through to a press determined to push an agenda that plays to the interests of its millionaire owners, politics is a fertile ground for satire and artistic commentary. The results, however, have been limited. The Traverse production of How to Disappear aimed at the savagery of the benefits system, only to resolve it through a science-fiction fantasy; Buzzcut’s Double Thrills programme has included performance that deconstructs oppression and celebrates counter-cultural identity; Arika invites artists working from queer and marginalised communities to question the relationship between creativity and activism.

Script-based theatre, on the other hand, tinkers with political intention without much effect. How to Disappear is a fine example of the lack of meaningful engagement: having set up a scenario that exposes the cruelty of the benefit system, it simply wishes away the evil, content to claim that a personal transformation is enough to rescue both ‘clients’ and officials from the tyranny of a system that cares more for business than the individual.

Trumpageddon went for it

While these have all articulated protest, and have entertained and educated, they are outposts of rebellion, either reaching limited audiences or addressing general concerns. There is no obligation to these organisations to take on more specific issues – or to change, as it would be a great loss for either Buzzcut or Arika suddenly to subsume their visionary curation of events beneath a dogmatic call to political action.

Other new work has been more explicit and focussed – Julia Taudevin’s Blow Off may have drawn a nihilistic conclusion, but it captures a broad sense of how patriarchal oppression impacts on the individual and expresses punk frustration – but the programme of The Lyceum, which artistic director David Greig regards as an engagement with contemporary society, seems reluctant, at times, to follow through its ambitions with immediate relevance, deferring direct assaults on Brexit to meditations on the past (Cockpit’s sumptuous staging by Wils Wilson rescued a strangely xenophobic script that examined displaced persons in the aftermath of World War II)or manipulating classical texts for contemporary allusions (The Suppliant Women of Aeschylus becoming a metaphor for the treatment of migrants). Even more disappointingly, the recent Tron presentation of The Brothers Karamazov majored in a discussion about the relationship between church and state in Czarist Russia, concentrating on a largely irrelevant historical idiosyncrasy of the source novel and ignoring the qualities of the novel that have allowed it to maintain relevance into the twenty-first century. Scripted theatre – although it has champions for new work in the Traverse and at Oran Mor’s Play, Pie and A Pint – is often undermined by its desires to revive plays from the past, plays that have often disappeared from the repertoire because of their historical contingency and present cultures and politics that resonate distantly to contemporary concerns. Placing political discussions in the past can allow the audience to displace responsibility: Restoration comedy, for example, frequently mocks the sexual morality of the fashionable set but, given its obnoxiously hypocritical double-standards, this satire doesn’t hit home in a society that is beginning to recognise the corruption of Harvey Weinstein, Donald Trump and the internet. If anything, it gets audiences off the hook of responsibility, providing evidence of progress. Future generations of scholars, no doubt, will be able to comment on how the various revivals of The Oresteia or Jumpy reveals the anxiety of the twenty-first century, and that the omnipresence of consumerism caused a tension between notions of theatre as art and entertainment. The role of the audience – largely middle-class – and the desire to pander to their broad beliefs – will be analysed, and the confluence of capitalist individualism and left-wing beliefs identified to explain why activist content was so frequently presented in a traditional, conservative format.

as seen as the Lyceum

Economics, especially the influence of the funding bodies, will be laid out and the movement towards another mode of performance explained, much as the neo-classical tragedy of seventeenth century France becomes a prelude to the bourgeois sentimental drama of the eighteenth century. In the meantime, theatre is failing in its political ambitions. While I don’t have any great enthusiasm to see a selection of plays revelling in a right-wing bias, the lack of diversity in the political perspective presented on stage suggests either a lack of imagination or a deliberate pandering to the audience’s exiting beliefs. Iphigenia in Splott, a success at the 2016 Fringe, is a case in point. Rightly lauded for a power solo performance and sharp writing that captures both regional detail and the wider impact of government policy on the poor, it was wrongly praised as ‘revolutionary’ when its only conclusions were a celebration of working-class resilience: far from pointing to solutions, or even attacking the causes of oppression, it is a powerful steam-valve for the audience’s anger, providing the illusion of political engagement. Against this, companies like Cardboard Citizens tour into venues, like shelters, to engage homeless people, aligning their means of presentation with their subject matter. Me and Robin Hood concludes with a collection for charity, asking the audience to go beyond simple assent to the politics expressed.

Attendance at a political performance, like the Lyceum’s programme, rather, becomes a form of virtue-signalling that demands no action: an end in itself, the public sphere of theatre becomes a mimesis of activism, in the worst sense. It effects no change, even encourages a sense of hopelessness, a point made in Ontroerend Goed’s Audience. The spirit of the agit-prop performance has been replaced by empty gestures. That isn’t to conclude that all of these works are irrelevant or unnecessary, or even beyond redemption. How to Disappear had some strong performances – Sally Reid, unsurprisingly, lent sympathy to a simplistic character, Cockpit imagined a way of using the auditorium to immerse the audience within the action. But without more explicitly political theatre, without the extremes of content and form, it never moves beyond a vague assent that things aren’t that great, are they?

It has a go at politics

from the vileblog http://ift.tt/2Cmu7K3

1 note

·

View note

Text

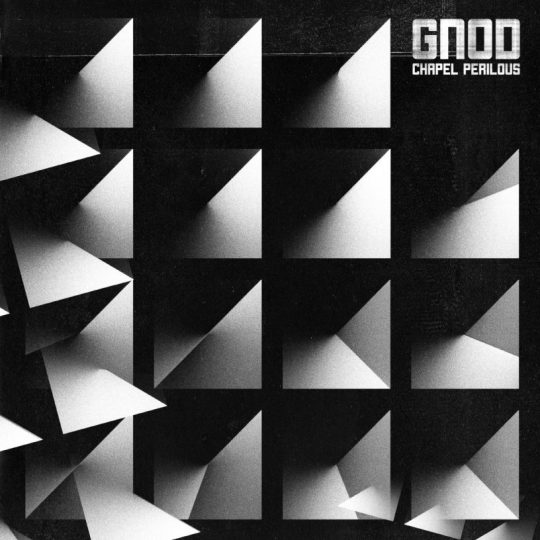

Chapel Perilous reviewed on Psych Insight

Album Review: Chapel Perilous by GNOD

Date: March 20, 2018

Author: Simon

GNOD are something of a enigma for me. Looking back over their discography few can deny that there have been significant highpoints, but I have to admit not all of it has landed with me. This conundrum, I guess, comes with what seems to be a constant desire to move on, and to try something different. If you’re going to be experimental then not everyone is going to get the results all the time. So it was for me with the collective’s last album ‘Just Say No To The Psycho Right-Wing Capitalist Fascist Industrial Death Machine’, an album whose sentiments of the title I could fully subscribe to, but overall felt to me just a bit too obvious and unimaginative. Don’t get me wrong I think ‘Bodies For Money’ is one of the best tracks of last year, and stands out as a high-point in the GNOD oeuvre, but while I acknowledge that the album was intended to be a stripped back statement it really didn’t strike a chord with me at all, and it is a set of tracks that I’ve come back to on more than one occasion to try to rectify.

What I guess I’m trying to say here in what is, for me, an unusually negative introduction; is that I don’t automatically assume that anything that GNOD does is going to be something that I rave over. What I will attempt to do though is approach the band’s music with as open a mind as I can… so here goes…

Well what I can say straight away is that ‘Chapel Perilous’ has had a much more immediate effect on me, it seems to me that there is much more going on here, right down to how the album has been put together. ‘Donovan’s Daughters’ is a massive fifteen minute track which opens ‘Chapel Perilous’, apparently honed through live performances during the bands long 2017 tour. Setting off simply it is not long before the hallmark GNOD guitar starts kicking in, angular and sporadic… you’re left in no doubt who this is. Then when the vocals come in I’m struck how much this iteration of the collective are indebted to post punk. There’s definitely something of the early eighties about this track… and I mean this is a good way. There’s PiL, Wire, Gang of Four… but then as ‘Donovan’s Daughters’ continues to intensity you get a sense of that being subsumed by noise to a certain extent, although the Lydonesque voice persists even though it struggles to be heard.

There is something wonderfully all encompassing about this… something that I pretty much felt I got on the third run through, and from then on its just been building inside my head as the noise becomes more industrial before taking a pause… almost a bridge… but if it is a bridge it’s somehow one that’s being built as you travel over it. No so much spontaneous, as taking the listener somewhere nebulous. Then BANG! Into the final movement with a massive riff just flying off into the stratosphere… into a heavy and dark cloud of unknowing.

These ideas take us into the heart of ‘Chapel Perilous’, a term which appeared in literature as early as the fifteenth century, and could be understood as a liminal state where we are exposed to experiences that disagree with our perceptions of reality; whether they be it spiritual, philosophical, social or even physical. A state which you could argue is at the heart of psychedelic music, and is central to this album. So while ‘Donovan’s Daughters’ may well take us to this state the following three tracks take us over the threshold. Tracks which it seems are developed much more in the studio with the involvement of Neil Francis who has returned to the GNOD collective for this project.

First up is ‘Europa’ a dark and unsettling piece that utilises some unusual percussion involving scrap metal and blacksmith’s tools, giving it something of a low realism underneath the vocal samples that advocates responsibility ‘towards the European system’. The sense of fracture here is obvious, the ‘Chapel Perilous’ for me here being the unknown future of the European Project.

‘Voice For Nowhere’ is equally bleak and anxiety driven, this sense of stepping into the unknown a clear and constant theme for the mid-section of the album. Here the post-industrial mantra hammering out a raised sense of consciousness that is anything but meditative and relaxing. Quite the opposite, the more you become subsumed by the rhythm that more uneasy you become. From what I’ve read about it there’s a danger that when you enter the ‘Chapel Perilous’ you may never leave… ‘Voice From Nowhere’ certainly draws you in to this liminal space, but the essence of the meaning here is that it’s up to you to get out again…

This is a state that is exacerbated by ‘A Body’ the third of the three ‘studio’ tracks, and probably the one that sums up the album for me. The vocals here are, to say the least, chilling and add a nuance that really takes this album to another level for me. This is a massively intense and destabilising track that personifies what I think GNOD are seeking to get across with the ‘Chapel Perilous’ motif… a place that confronts and collides with our sense of reality… it is a track that does not so much act as a siren voice guiding towards the liminal as pulls us straight into the heart of our unknowing…

Taking us out the other side is another number that has been honed on the road. ‘Uncle Frank Say Turn It Down’ is a heavy uncompromising noise track that snaps us out of our reverie and brings us back to the ante-chamber of perceived reality… we’re by no means back into the everyday, that’s never going to happen with GNOD, but we are back amongst the familiar this pummelling track being a welcome respite from the dislocation of the three central tracks of the album.

I won’t call ‘Chapel Perilous’ a return to form because there are plenty people whose opinions I value who thought ‘Just Say No To The Psycho Right-Wing Capitalist Fascist Industrial Death Machine’ was a great album. What I will say though is that through ‘Chapel Perilous’ I have come back to GNOD. For me this is an album that is far more subtle than its predecessor, an album that takes you into and out of the liminal void of the ‘Chapel Perilous’ through the bookending tracks, and then provides anyone willing to listen closely enough with an experience that is bleak and auto-confrontational, an experience that is weirdly meditative yet has that opposite effect. This is not an exploration of mindfulness, neither is it one of mindlessness. Rather it takes you into a nihilistic realm and rather brutally leaves you there… kicking the props of reality from under you… forcing you to confront your own truth… your own reality… enter at your peril!

-o0o-

‘Chapel Perilous’ is available to pre-order now from Rocket Recordings here.

Follow me on Twitter @psychinsightmsc, Facebook, Instagram, and Bandcamp

Original here

0 notes