#or actually to Lexember as a whole

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lexember Day 5: Wák/Valak

The Proto-SZ word *wadak meant "family," a concept that is very important across many cultures.

wák, *wadak, /wák/ - (n) family, household; (n) we, 1st person plural pronoun implying a degree of closeness

In Lu Izhél, it is one of many words that can be used as a pronoun. It is a first person plural pronoun which can be inclusive or exclusive, and implies some connection within the group - it might refer to a literal family, a group of friends, a military unit, or other similar groups, but it would not be used for a group of strangers.

wák suutta uwák ise inák 1P see-PAST ACC-family GEN-person GEN-victory We saw the emperor's family.

In most of the posts so far, the Lu Izhél form is the focus, and the Svinık form is just a side note. Here, it's actually worth talking about!

valak, *wadak, /’βa.lak/ - (n) family, clan

Families are core to the political organization of Svinık society. Loyalty to the family is essential, above any other association, and the actions of any member of the family reflect upon the whole group. Similarity to the word valık "root vegetable" is entirely coincidental.

valak ik vadzım shak family GEN-1S 3P-side INST-1S My family rides with me

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lexember 2024: Day 12

Sorkish

máqa- [ˈmɑqæ] v. bury → máqarm [ˈmɑqærm] n. burial → máqban [ˈmɑqæn] n. grave

Chytari

kuyuș [ˈkujuʃ] n. death → kuișeya [kuɪ̯ˈʃɨjɐ] v. die → kuyuși [kuˈjuʃi] adj. dead giàuniya [giʔɑu̯ˈɾijɐ] v. bury (from gi "into" + auni "land, earth, soil" + -ya "infinitive marker") → giàunikas [giʔɑu̯ˈɾikɐs] n. burial auțun [ˈɑu̯d͡ʒun] n. grave (from auțeya "protect" + an unknown element)

also have some lore crumbs: sorkans first cremate their dead, then they bury their ashes. according to the holy book, the two gods created sorkans from fire and so return to the fire is a symbolic end to one's life that ensures their soul can be reborn one day. so understandably, if the body of a sorkan is not cremated, it never enters the afterlife, meaning that one of the worst things you can do to your enemy is to ensure their body cannot be cremated (this actually gives a WHOLE new layer to sorkans in exile damn. you are not just sending them away from their family and their land, you straight up banish them into nothingness because lets be honest its very unlikely they will get a proper burial outside of sorka)

as for the chytari, most of them bury their dead into the soil, believing that offering their bodies to the earth is a thanks for everything it has given them

#sorkish conlang#chytari conlang#conlanging#conlang#constructed language#conlangs#kélas#lexember#lexember 2024

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tepatic Anti-Claus

Lexember #24, Tsapay

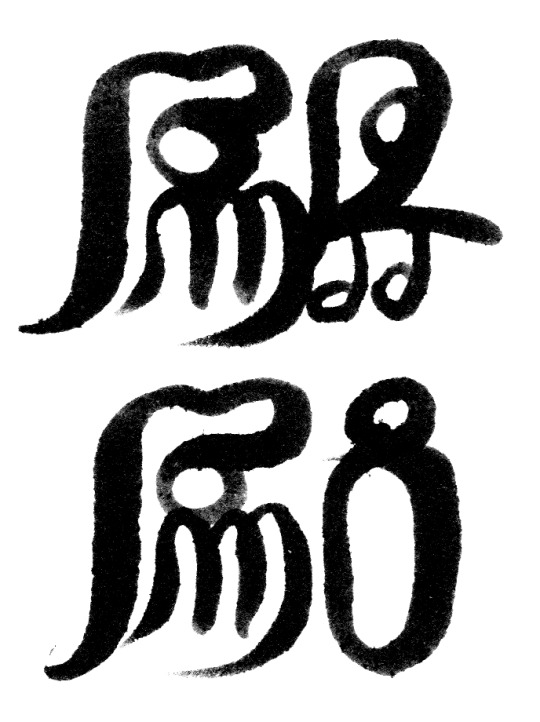

Tsapay (Tepatic Romanization, capay [t͡sa:paj]) refers to a monster of folklore. It is spelled with two glyphs ca(p) pay. The first glyph uses the demon semantic determiner on the left side, and on the right side is the phonetic determiner, the glyph cap ‘wax,’ showing drops coming out of an ear. The second glyph is demon determiner + pay ‘wart’ - a previous Lexember word.

ABOVE: Tsapay in Tepatic glyphs

Like most ancient names, the etymology is uncertain, but it has nevertheless been folk-etymologized as due to the monster having warts and greasy skin.

The Tsapay is kind of like a reverse Santa Claus. To understand it is necessary to know a bit about Tepatic holidays.

In Tepat, the New Year is the biggest holiday of the year - in fact, 5 days long, consisting of the 5 days out of 365 that do not fit into a 30-day 12-month system. (The year also starts on the equivalent of our October 25th, but ignore that for now.) Despite being a big event, it is viewed and celebrated very differently from Earth. Tepatites believe that whatever you do on New Year sets the pattern for the year, so anything you do should be done perfectly. If you doze away lazily on the holiday, you are doomed to be an unproductive slob for a whole year with all the negative consequences that follow from that. No, in order to be sure you are a bright, alert, timely person all year, you should get up earlier than usual on New Year - at minimum, to see the sunrise. Hence, you should also go to bed as early as you can on New Year’s Eve. Before sunset is best, but you must absolutely not be up past midnight. Anything left undone by midnight, and your goals will remain unfinished for next year.

More about Tepatic New Year:

https://www.tumblr.com/yuk-tepat/131244433960/new-year-in-tepat?source=share

https://www.tumblr.com/yuk-tepat/131308699272/new-year-in-tepat-ii?source=share

https://yuk-tepat.tumblr.com/post/154867637619/lexember

To keep them in line, adults tell children in Tepat that if they are out after dark on New Year’s Eve, they will stolen by the Tsapay. What began as a tale has gotten more elaborate, with patrols of large men wearing costumes slinking around at night to fool kids who may be peeking out the window. When boys get too old to be scared anymore, they are conscripted. After being kidnapped by Tsapay, they are revealed his imaginary nature. (Naturally, they are told the truth AFTER being kidnapped, so there is one last chance to make them pee their pants.) After this, they are trained to impersonate Tsapay for younger children. This is an important rite of passage. And the whole society conspires to keep it secret.

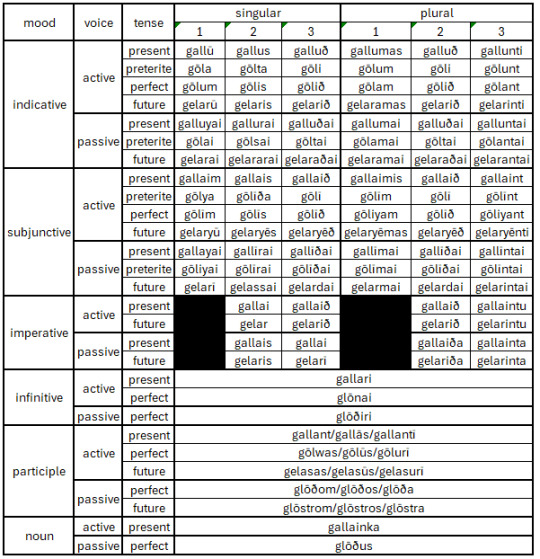

ABOVE: An artist's depiction of Tsapay

This Tsapay is typically identified with one of the ‘leftover’ demons of Tepatic mythology. After being defeated by mankind, the Demon King and his legions retreated to a mountain (which became a volcano), and were imprisoned in it - but not before taking captive one of the human leaders, who continues to fight an eternal battle against the monsters deep in the earth. At least one of the king’s legions, though, fled and survived in hiding on the surface of the earth.

Another connection has been made with the mythology of the pre-Tepatic Milim people. The Milimites feared a long-nosed monster that threatened to eat the world at the end of each year, before being defeated by the heavenly kings with the help of, you guessed it, blood sacrifices.

More about human sacrifice:

https://www.tumblr.com/yuk-tepat/678299852131729408/2021-lexember-31-sel?source=share

https://www.tumblr.com/yuk-tepat/735912532678721536/lexember-6-8-tsaltep-kyeng-ngy%C3%BBp?source=share

This may be connected to the folk custom of leaving meat out to ‘make Tsapay go away’ (which is then actually eaten by dad).

Colloquially, anything used to keep people in line, particularly punitive measures of dubious effectiveness, or things that appear threatening but are not dangerous, are called Tsapay too.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy 1st of Lexember!

I'm doing another attempt at a "Belgic" language (intended to be intermediate between Gaulish and Germanic, also with some Italic features, because it turns out a lot of those just fall out naturally when you sit between Celtic and Germanic), with this outline being intended to be a fairly early stage, roughly contemporary with Proto-Germanic (so around 5-1st Centuries BCE)

In keeping with that, it has a vigesimal system with a long-hundred (120) and long thousand (1200) and the basic (masculine) cardinals are:

1: oinos /'ojnos/

2: duwa /'d̥uwa/

3: treyis /'tʰrejis/

4: piðūr /'pʰiðu:r/

5: pempi /'pʰempʰi/

6: sehs /'sexs/

7: siftum /'siftʰum/

8: aɣdau /'aɣd̥aw/

9: neun /'newn/

10: dehun /'d̥ehun/

20: wīɣuntī /'wi:ɣuntʰi:/

120: kantom /'kʰantʰom/

1200: ɣeslī /'ɣesli:/

Numerals 5-10 are indeclinable, whilst 20, 120, and 1200 are actually nouns (feminine, neuter, and feminine respectively) referring to groups of that many instead (and so taking a genitive plural noun, rather than agreeing with the noun they quantity)

The word for number is rīmom /riːmom/, and in the plural (rīma), this can refer to the numerals as a whole.

This language is currently called Damwās Velgaiɣa /'damwa:s 'velg̥ajɣa/, from the root *bʰelǵʰ- "to swell", with the sense "to be wrathful"

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lexember 11

Kertazma, [kɛɾˈtaz.ma] (n.) | cousin, relative of the same generation

So to explain this word we once again have to look at its root words which today are *kert and *jazma.

*kert survives unchanged as kert and means 'fruit'. Since the beginning of Elvish this word has been used a metaphor for offspring and the Shembaba word for child is the diminutive: kertö.

*jazma used to mean branch (of a tree) but now basically only shows up as a derivational suffix to derive things that have something to do with the original. So while your cousins aren't your own fruit, they are someone close to you's fruit, so that's the whole story behind it.

I haven't fully worked out the Shembaba kinship system yet but what I do know is that young Elves tend to grow up with their age cohort and that they are just as close to them as any cousins would be, hence the polysemy. But yeah, I might one day make a post about the fully kinship system, so stay tuned!

On a more meta level I'd like to talk about inspiration and the ever-hated question a-priori-conlangers get asked: 'What languages is your conlang based on?' And while my first answer will always be 'I exclusively do a-priori-conlangs that exist in worlds that have nothing to do with the languages of Earth (made up or not) and I'd be unsatisfied to the point of feeling ashamed if I actually based my languages on a specific language' I will let you in on a secret:

I chose this exact shape of *jazma to get derivations that resemble High Valyrian. And I did this with a bunch of derivational suffixes and the like. Writing up all the explanations for my lexember words, in fact, makes me embarrassingly aware of how much I did that - but I just wanted my players to have a sense of familiarity with the sound and aesthetics of Shembaba. After all, it was to be the Elvish language at our table. I strongly suspected that they'd enjoy this language much more if it resembled what they had previously encountered as Elvish/High Fantasy languages. Not only that, it had to look and feel like a language that was ancient, that had prestige and that generations on top of generations had done music, poetry and art in. So yeah, I leaned heavy into High-Valyrian-isms. But, to be fair, not only that – the aesthetics of Elvish were heavily influenced by Latin and Ancient Greek as well, because these are the canonical ancient languages Central Europeans grow up with. It didn't stop there, though - there also is some Russian, Japanese, even Turkish and Finnish in there.¹ Why exactly these? Because I felt like it. And to say that this is a definite, extensive or limiting list would be silly. But yeah, if you conlang, you might sorta understand what I'm getting at.

Maybe somewhat interestingly, I never really looked much at QUenya and Sindarin. Like a lot of conlangers I had heard of them pretty early on, and I have some idea of what Tolkien did with them. But I made the maybe mostly subconcious decision to not look them up too much to not throw even more outside influence onto Shembaba. Maybe I had felt a sense of pride where I wanted my Elvish to be its own thing completely separate from what Tolkien did. I know, this is a bit ironic considering what I just admitted about High Valyrian, but hey. Every human being is a walking contradiction.

¹To be clear, when I say these languages served as inspiration, I really only means this in the aesthetic sense (whatever exactly that even means). Surely, if you looked at the grammar of Shembaba you will see similarities to real world languages - just like how between any two real world languages there will be some similarities. However, I do wanna say that I consider my work my own work - and while I am infinitely grateful for David Peterson's work and appreciate his influence on me, I will maintain that Shembaba is its own thing that ´, while it pays the occasional hommage - for the sake of my players just as much as me - is definitely not just a lazy copy.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Valya Vednesday #9

I bet you didn’t expect extra posts on top of the Lexember ones! I didn’t either, but I thought of some stuff to say so here we are. This is sort of a “miscellaneous bits and pieces” post.

First, I noticed a mistake in the Lexember 2 post: in the Valya orthography every single example of nu is written as ngu by mistake. You can see the correct spelling of mblatanu in today’s Lexember post and extrapolate from there.

Second, I realized a funny thing about yesterday’s example sentence. It is correct (as far as I can tell), but there’s actually a bit of ambiguity to it, probably more so in writing than when spoken aloud. The sentence includes the phrase ni nya, meaning “three ducks.” However, because Valya orthography doesn’t use spaces between words, it could also be read as ninya, or “a duckling.”

Diminutives were discussed in detail in this post, but the short explanation is that to form a diminutive noun, you repeat the first bit of the word. “Bit” here refers to a mora in the proto-Valya stage, which is a little fuzzier when it gets to the modern language. You could say “duckling” as nyanya by repeating the whole word, or as ninya by only repeating the first half of the syllable (ish). I would imagine that when speaking there would probably be some difference in stress, intonation, or syllable length that would mean that ni nya and ninya could be distinguished. In writing, though—nope!

Third, I wanted to show a bit of my documentation! A month or two ago I decided to try out Obsidian, after having seen @conlangery using it on a few Tongues and Runes livestreams. It took a little bit of figuring out but I have it set up a way that looks nice to me, and it’s very convenient for storing the Valya lexicon! I can have a separate page for each word, with links to related words, notes on spelling, and all sorts of other information. Here’s one of the most recent entries:

At the end are tags to mark this entry as both a noun and a compound noun specifically. I’ve also got list entries for each part of speech, and two big entries for the complete English → Valya and Valya → English lists. Compared to my previous methods of using text files and spreadsheets, this is way easier to navigate and organize. There’s even a graph view where you can even see all of the connections between the entries! If I zoom out you can’t see the labels so here’s just part of the interconnected web that is Valya:

(I promise this isn’t an ad—it’s a free program!)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

We're Back Baby!

So, after nearly two years of radio silence, we're finally back! Sorry about that everyone, we've been having a hard time maintaining our social media presence, and this place felt the brunt of it. But we're now back and with a brand new social media manager, who should make sure we never go this quiet again.

Now, for those who have forgotten who we are, and those who discover us now thanks to this post, a quick introduction:

We're the Language Creation Society, a California-based non-profit organisation with international reach and membership. Our main purpose is the promotion and furthering of the art, craft and science of language creation (conlanging) through conferences, books, journals, outreach activities, or other means (like literally, it's in our articles of incorporation and everything!). Basically, we're an organisation of conlangers, for conlangers, and for conlanging as a whole.

How do we do this? By many means. We've got a Jobs Board for conlangers who want to practice their craft professionally. It's set up so as to ensure people who do conlanging for others are paid fairly for their work (it's a work in progress) and don't end up in disadvantageous contracts. For people who are interested in doing something conlang-related academically, we've got the LCS Presidents' Scholarship, which is a (modest) amount of money we award to people with interesting academical projects that align with our main purpose. For general conlang-related projects, we've got the LCS Grants (currently the most famous project we supported financially is probably the Conlanging, The Art of Crafting Tongues film, the first full-length documentary on conlanging ever made). But our main article is the Language Creation Conference, for many conlangers the only way for them to ever meet other conlangers face to face. So far we've organised 8 face-to-face conferences in North America and Europe (all with live streaming and online participation for those who couldn't join), one online-only conference (thanks COVID), and due to circumstances outside our control our next conference will be online-only as well. But we'll get back to doing face-to-face conferences someday!

Of course, all these activities cost money. Which is why we encourage people to join our organisation as a member, which will give you many benefits, including the power to help decide what we actually do. The more people join us, the more we can do to help conlangers and conlanging as a whole. Not just thanks to a larger budget (we fully depend on membership fees for our income, and everyone working at the LCS does so as an unpaid volunteer), but because you can bring your ideas to the table and help us provide the best support we can to the conlanging community in general and our members in particular.

So this is us. In the next weeks, expect more announcements from us as we pick up steam (I'll also share videos from the latest Language Creation Conference from our Youtube channel). In the meantime, feel free to reblog this post so everyone can be made aware of our return to Tumblr, and our Asks are also open to anyone who has any question concerning us or conlanging in general. We're here to support you, so don't hesitate to get in touch!

And since it's the season, happy Lexember everyone!

#language creation society#lcs#language creation conference#lcc#conlang#conlanging#conlangs#who we are

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

For Lexember this year, I’ll be using Ra Na i Ku, which I’ve worked on on and off since about April or so. It’s a priori and set in a fantasy conworld. I’m hoping to get a reference grammar for it finally written up soon (along with two other languages of mine, Mane Injsikut and u:w-ata).

I’ll start with some kinship terms, and then move on to other domains (animals, abstractions, natural phenomena, etc).

The name translates roughly to “The Speech of the River”, referring to the Nau River by which its speakers live. Although since ku as a noun also translates to “breath”, the name could be more poetically rendered as “The Breath of the River”.

It’s pretty strongly head-final (and thus SOV), nom-acc (with some complications), and almost entirely isolating. Verbs are closed class (with maybe ~100 items), so don’t expect too many showing up.

Some interesting features:

The aforementioned closed class verbs, à la Kobon.

Imperative clauses are marked by dedicated imperative second person pronouns as subjects. (Mood/modality is else indicated by particles.)

The third person pronouns double as definite articles. (Although “definite” is a misnomer, because it’s actually specificity that’s marked.)

Subjects of transitive verbs cannot be inanimate, unless followed by a postposition. What postposition this is depends on whether the event described is the result of underlying agency or not. (Ie, “the stone killed the man” must be marked for whether or not it simply fell or was thrown.)

Alignment/voice is based on the inherent transitivity and accusativity of the verb, which leads to various syntactic/semantic complications.

Transitive verbs must occur with a direct object, even if it’s just a dummy pronoun.

Tense is unmarked, but telic verbs are by default understood as past, and atelic verbs as present. (Also, telicity and accusativity usually occur together, but there are exceptions.)

There is no voicing distinction in stops, but there is one in fricatives, as what were once voiced stops became fricatives in all environments. Furthermore, the fricative series are also mismatched (/s, h/ vs. /β, z, ʒ/). (Proto-Nauic */g/ merged into /h/, there was never a voiced counterpart to /q/, and Proto-Nauic had post-alveolar affricates that patterned with the stops.)

The rhotic is an English-esque abomination that is usually /ɹ/, but often more retracted than that, and is sometimes /ɻ/. Also it has creaky voice, which spreads to surrounding segments (at least vowels), and it affects the quality of adjacent vowels.

Complicated onset clusters, often doing violence to the whole idea of a sonority hierarchy, including such monstrosities as /nz/, /ʃkɹ/, and /mkɹ/, but no clusters, and in fact only /m, n, ɹ/, allowed in codas.

A purely quinary number system, with a syntax for forming higher numbers similar to that of Mandarin.

Obligatory phoneme inventory (and romanization, where it differs from IPA):

The culture of the speakers is inspired by various sources, including Oceania, “Old Europe”, and the Bronze Age Near East, as well as parts of Africa and the Americas, but closely follows none of these. Technologically, they’re at the cusp of widespread use of bronze, as well as true writing. Potato-based agriculture has just taken off, and the first small cities have sprouted up. There’s something of a strong, but recent, cultural dichotomy between those who live in the Five Cities (Mkran i Sha) themselves, and those who live in the surrounding countryside, the so-called Drylands (Krasai Huvi). As for religion, they’re animists, with a belief in reincarnation. The surrounding cultures are neolithic and mostly garden agriculturalists, and most speak related Nauic languages.

As stated above, there’s almost no morphology, although there are a few derivational processes: a productive augmentative suffix and diminutive prefix (kar “stone” → karan “boulder”, kikar “pebble”) and a semi-productive collective plural (shau “tree” → shasau “forest”). (Non-collective plural is unmarked and only explicitly indicated by by the use of the plural article, or else by actual numerals.) As far as compounds are concerned, they’re very common, though are (almost) always phonologically phrasal.

Happy #Lexember!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

3rd of Lexember

Today I'm doing a more proper lexember, with the word gallū /'gal:u:/ "to be able to, can"

The verb is irregular, but not suppletive, all forms come from the root *gelH-

The present stem is from the Ø-grade of the nasal infix present i.e. *gl<n>H- with assimilation of the n to the l (seen also in Welsh gallu). The conjugation here is slightly irregular, as it retains the vowel from the vocalised laryngeal, something that is elsewhere replaced with the typical thematic vowel

In keeping with the theme of Velgaiɣa being intermediate between Celtic and Germanic, the verbal system is reduced from that found in the Ancient Celtic languages (or better attested in Italic, which seems to have been largely parallel in terms of the categories attested, even if the specific forms differ). In particular, instead of an imperfect, perfect/preterite/aorist, and pluperfect, we have a preterite and perfect, with no future perfect either. The perfect is also restricted to the active voice

The preterite uses a mix of aorist (as in this case) and (more typically) perfect stems as in Celitc (and Italic), but wholely perfect endings (as in Germanic), rather than the innovative endings found in Celtic and Italic (likely originally aorist endings followed by perfect endings). As such, it broadly continues the Late PIE perfect, but has been reinterpreted as a general past tense (as is common cross-linguistically)

The perfect is, in origin, a pluperfect, but was pulled into the position of perfect when the perfect became a preterite. It has the same stem as the preterite, but uses imperfect/aorist endings (as in the Latin pluperfect)

This particular verb has a "rhotic" future, the regular continuation of the Late PIE sigmatic future when the s is added directly to the root or with a preceding vowel (including from an inserted laryngeal), as *s regularly develops into r following an unstressed vowel (following a stressed vowel it instead debuccalises to h, unless followed by an additional consonant, including a *y or *w which would subsequently be lost)

The passives are in -i as in Germanic, rather than in -r (as in Celtic and Italic)

The non-finite verbal system is actually slightly larger than seems to have existed in either Celtic or Germanic, mostly because I love non-finite verb forms:

Present active infinitive: this is a locative of an s-stem noun, as seen in the Latin present active infinitive. It is derived from the root itself, not the present stem, so must be learnt separately when learning the paradigm of a regular verb. It was originally always e-grade (which would give *gelari), but in some instances like here, the present stem has spread to it by analogy

Perfect active infinitive: this is a dative of a nó-stem noun, as seen in Greek, and similar to the Germanic infinitive (although that is an accusative). It is derived from the root itself, not the perfect stem, so must be learnt separately when learning the paradigm of a regular verb. Whilst it does use the same ablaut grade as the perfect passive verbal noun, the n typically assimilates to a preceding consonant, making the relationship opaque

Perfect passive infinitive: this is a locative of an s-stem noun with the -t- suffix seen in the perfect passive participle

Present active participle: this is the regular old present active participle

Perfect active participle: this is the old stative participle

Future active participle: this is a stative participle with the future stem

Perfect passive participle: this is a tó-stem adjective, as seen in Latin and, possible, Germanic weak verbs

Future passive participle: from a thematisation of a verbal noun in -otr-/n- formed with the future s-suffix (this same -otr-/n- suffix is one of the more plausible suggestions for the origin of the Latin gerundive or future passive participle, albeit from the -otn- form, which would give -tt- here instead)

Present active verbal noun: this is intended to parallel the Germanic "gerund" in -ungō, the origin of which is unclear. One proposal has it from an earlier form with a labiovelar, in which case we'd expect a verbal noun in -mp- here instead, but I wanted the clearer parallel to Germanic so decided to go with a plain (or palato) velar instead

Perfect passive verbal noun: this is the classic PIE supine tu-stem verbal noun. It is derived from the root itself, not the perfect stem, so must be learnt separately when learning the paradigm of a regular verb (although the perfect passive infinitive, perfect passive participle, and future passive participle are also derived from the same stem)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tlette Tlursday #2

Today’s topic is syntactic gemination! On Lexember 4 (lé) I talked about this phenomenon for the first time, and @yuk-tepat asked “Is there a diachronic explanation for why syntactic gemination occurs?” The answer was a bit too long for a reply so it’s getting its own post.

So first of all I basically just stole this idea from Italian. It also occurs in Finnish, but I didn’t know that until quite recently. I first came across the idea in a video about Italian pronunciation, which discussed the phrase tra poco, meaning “soon.” The word tra is a preposition coming from Latin intrā, which had a long final vowel. Even though the length of the vowel has been lost in Italian, it is preserved as the gemination of a following consonant, so tra poco is pronounced as /trap.ˈpɔ.ko/ (or /tra‿p.ˈpɔ.ko/ if you want to show that explicitly).

In Tlette it comes from the same general place. Proto-Tlette (or Kaleate) allowed CVV syllables, but a later sound change basically transferred the length from a vowel or diphthong onto the following consonant. This is the source for many of the doubled consonants within Tlette words. The word elle was originally *eele, with a long first vowel. The vowel got shorter but the consonant got longer, to preserve the timing of the word as a whole.

The same thing happened with no’’i, previously *neuʔi. There the first syllable had a diphthong instead of a long vowel, but the double vowel *eu squished down to *ew, which later became o.

Syntactic gemination is just this same process occurring at word boundaries. The word lé was originally *lee, and just like intrā shortening to tra it shortened to lé and caused following consonants to lengthen. If the next word begins in a vowel or a consonant cluster, it isn’t affected.

The accent mark in lé is just there to show that the gemination could happen. The singular nonhuman pronouns are actually a homophone pair, ku and kú (nominative and accusative respectively, originally *ko and *kol). They are pronounced identically in isolation, but only the latter causes gemination. It originally ended in a consonant and not a long vowel, but before the length-transfer sound change occurred the final l vocalized to make a diphthong.

Since original *o became u, in modern Tlette all instances of non-nasal o come from diphthongs like eu. That means that all words ending in o trigger syntactic gemination, and within words o is always followed by a geminate consonant or a cluster. Because this is so consistent, single-syllable words ending in o (like po) don’t need to be marked with an accent, since there’s no possibility for a homophone that wouldn’t cause syntactic gemination.

The same process also affects certain consonant-final words, like rıkk, originally *ruuqa. The final vowel was lost and the same transfer of length from the first vowel to the following consonant occurred, but the consonant is only pronounced as long when the next word begins with a vowel.

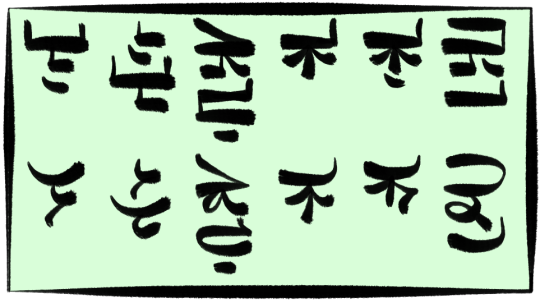

In the Tlette alphabet, there is a small accent-like mark that indicates both stress and gemination. It isn’t 100% consistent, but it generally follows stressed vowels and precedes geminate consonants, and is the equivalent of the accent mark for words like lé. In cursive Tlette, this mark joins with the preceding stroke. Below are, in order, lé, elle, no’’i, ku, kú, and rıkk. Since the geminate in no’’i follows an o, the mark is absent from that word.

9 notes

·

View notes