#okabae

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Why The Niger Delta Should Support The Nee Tax Reform But With Some Caution.

Being my response to questions raised on the above subject matter from journalist at the Gatwick Airport London The issue of the new tax reform in Nigeria in the context of the agitations for resource control and management is not only complex but also has serious implications for addressing the core demands of equity, justice and prosperity of the people who have suffered despicable conditions…

0 notes

Text

IYC Western Zone Affirms Support For Otuaro, Okaba, Warns Distractors To Desist

By Blessing Ebareotu The Ijaw Youth Council, Western Zone expresses utter displeasure against the misguided comments by a faceless and aimless group under the aegis of Project Niger Delta led by one Princewill Timipre targeting the National President of the Ijaw National Congress (INC), Prof. Benjamin Okaba following his endorsement of the Administrator of the Presidential Amnesty Programme, Dr.…

0 notes

Text

Tosa kinno-to, Okaba Ibo

#art#ryu ga gotoku#yakuza#akira nishikiyama#like a dragon ishin#yakuza ishin#ishin#okada izo#studying from my goat wilddreamz :)

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Chanoyu Hyaku-shu [茶湯百首], Part V: Poem 108.

〽 Kōgō to kan to habōki oku-toki ha migi-ba hidari-ba gimmi-shite oku

[香合と鐶と羽箒置く時は 右羽左羽吟味して置く].

“When placing the kōgō or¹ kan with the habōki, [you] have to examine [the habōki] closely [to determine whether it is made from] right-feathers, [or] left-feathers, when setting them [on the shelf].”

Migi-ba [右羽]² means a feather, or feathers³, taken from the right side of a bird -- these feathers are widest on the right side of the rachis.

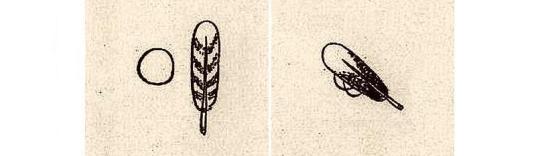

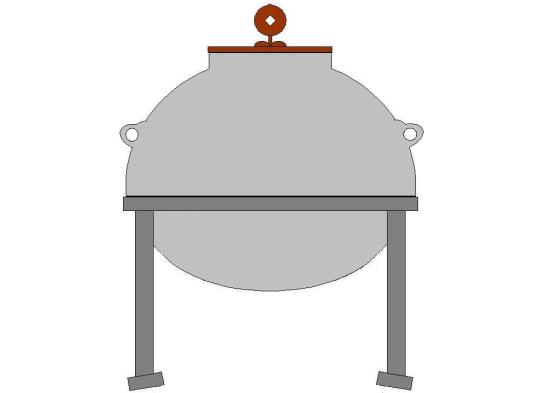

In Rikyū’s Nomura Sokaku-ate no densho [野村宗覺宛の傳書]⁴, the arrangements of the kōgō (left) and kan (right) with a migi-bane habōki are shown in this way:

In other words, the kōgō and kan are to be placed on the right side of the habōki -- in the latter case, with the widest part of the feathers overlapping the kan, as shown.

Hidari-ba [左羽]⁵ refers to a habōki made from feathers taken from the left side of a bird. Such feathers are widest on the left side of the rachis.

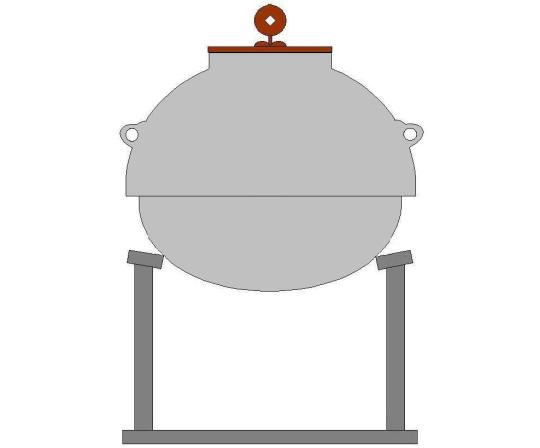

When placed on the shelf together with a hidari-bane habōki, the kōgō and kan should be disposed as shown below.

Again, the arrangement of the habōki together with the kōgō is shown on the left, while that where it has been placed with the kan is shown in the right sketch.

Because the way the utensils should be arranged depends on the nature of the feathers from which the habōki was made, it is important for the host to ascertain (ginmi-suru [吟味する]⁶) whether it is a migi-bane or hidari-bane before proceeding to lay out the arrangement.

Once again, this is another poem that is found in both Jōō’s Matsu-ya manuscript, and in the Jōō collection that was preserved by Katagiri Sadamasa.

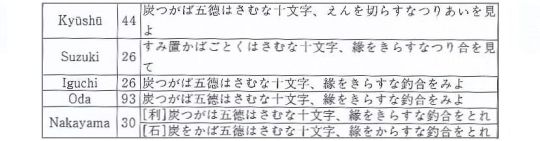

The differences between Sadamasa’s version and what is found in Jōō’s manuscript are synonymic, and so do not have any bearing on the actual sense of the poem:

〽 kōgō no kwan no habōki kazari-okaba migi-ba hidari-ba ginmi-shite oke

[香箱のくわんの羽箒かざりをかば 右羽左羽吟味してをけ].

“If [one] is going to place the kōgō⁷, the kan⁸, on display together with the habōki, [you] must⁹ scrutinize closely [to determine if it is made from] right-feathers [or] left-feathers, when placing them [on the shelf].”

_________________________

¹The particle to [と] should more literally be translated “and.” However, this might lead to the impression that both the kōgō and kan can be arranged with the habōki at the same time -- which is never the case.

²Migi-ba [右羽] is more usually read migi-bane. Migi-ba seems to have been used for poetic reasons (i.e., syllabic count).

Migi-bane are widest on the right side of the rachis, as can be seen above.

³Ordinary habōki are made from three feathers*, joined together at their calami† by a handle -- that may be either made of dried bamboo-sheath or wood (usually lacquered)‡.

The ultra-wabi ichi-wa [一羽] habōki, however, which was created by Sen no Dōan**, is made from a single feather, without a handle.

Ordinary habōki are made either using migi-bane [右羽] (right feathers) or hidari-bane [左羽] (left feathers). Habōki made from migi-bane are used with the furo; those made from hidari-bane are to be used with the ro††.

Habōki made from three identical central tail-feathers (which are symmetrical -- the left and right sides are of identical width, and are called moro-bane [雙羽], as seen above) were originally the preferred habōki for use with the daisu‡‡.

Habōki intended for use in the larger rooms are made from feathers that are between 8-sun and 1-shaku long; those for the small room should have feathers 5-sun long, and are consequently known as go-sun-hane [五寸羽]***. ___________ *The three feathers were originally supposed to be absolutely identical in size and shape, if not pattern. Today it is almost impossible to find habōki made like this. Rather, the top and bottom feathers are roughly the same size (though the bottom feather has an inferior color or pattern), while the one in the middle is smaller, and in every way inferior to the other two. This reflects the way that chanoyu has evolved from the early days down to the present (where appearance is more important than the true nature of things).

†The calamus (plural calami), sometimes called the shaft, is the lower part of a feather which lacks barbs, and which terminates in a point.

‡The handle of the original habōki was always lacquered. Some scholars ascribe this kind of habōki to Jōō, but it almost certainly predates him by decades, if not centuries.

The handle covered with bamboo sheath (which usually has a wooden core) is said to have been first made by either Jōō, or Rikyū.

The wood, in either type of handle, is bored with three holes into which the calami fit, and into which they are glued.

**The story is told that the teenaged Dōan (at a time when the family’s finances had not yet been stabilized) found an old mayu-buro [眉風爐] in the local dump, that had been thrown away because the mayu had been broken. He took it home, and cut away the remaining parts of the mayu, so that the sides of the hi-mado extended in a straight line up to the rim; after which he rubbed it with several coats of lacquer, and so used it for the style of wabi-no-chanoyu that he practiced.

Because this furo had been a broken piece, he felt it was wrong to use an ordinary habōki with it, so he found a large right-feather, and used that, without a handle, as his habōki when serving tea with this furo.

††Cf. poem 41:

〽 habōki ha furo ni migi-bane wo ro-toki ha hidari-bane wo ba tsukau to zo shiru

[羽箒は風爐に右羽を���時は 左羽をば使うとぞ知る].

“With respect to the habōki, in [the case of] the furo, [it should be] a migi-bane; [but] when using the ro, a hidari-bane should certainly be used: [you should] understand [this]!”

The URL for the post entitled the Chanoyu Hyaku-shu [茶湯百首], Part II: Poem 41, which discusses the relevant poem, is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/755652293596217344/the-chanoyu-hyaku-shu-%E8%8C%B6%E6%B9%AF%E7%99%BE%E9%A6%96-part-ii-poem-41

‡‡It is extremely difficult to find three central tail feathers -- which would have had to come from three different birds -- that are identical in every way. Thus moro-bane habōki were always exceedingly rare, and very costly.

While it was originally taught that the habōki (like the chasen, chakin, hishaku, and chashaku) should be used only once, the rarity and high price of the moro-bane habōki argued against this practice, so that such things would be kept carefully, and reused whenever appropriate. This eventually became accepted practice for all habōki.

***Because this was the rule from Rikyū’s day until the beginning of the Edo period, habōki made from the larger, beautiful feathers were either thrown away, or else put into storage.

Beginning in the early Edo period, when antiques were preferred, people began to search their storehouses, to find old utensils that had fallen out of favor during Rikyū’s push for simplicity. And since the only habōki found in storage were those made from the larger feathers, people started using them even in the small room. As a result, while not really unknown today, go-sun-hane [五寸羽] are rarely seen in modern chanoyu.

Also, because the ro was originally supposed to be used in the small room all year round, ordinary go-sun-hane are made from hidari-bane, even today. But after the use of the furo (during the summer months) came to be accepted in that setting (during the summer of 1587), go-sun-hane made from migi-bane came to be the appropriate habōki to use in the small room with the furo.

⁴The Nomura Sōkaku-ate no densho [野村宗覺宛の傳書] is dated “an auspicious day” in the Ninth Month of Tenshō 9 (which was the Year of the Snake)*.

Though the identification of Nomura Sōkaku with the military man Nomura Naotaka [野村直隆; his dates are unknown†] is tenuous, it is not unreasonable, given his period and well-documented associations‡.

Naotaka is first mentioned (c. Eiroku 13 [永祿十三年], 1570) as being an adherent of the daimyō Asai Nagamasa [淺井長政; 1545 ~ 1573]; though, after the defeat of the Asai clan (at the hands of Oda Nobunaga), he joined Nobunaga, and then continued to serve Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who gave him a fief of 20,000 koku at Kunitomo [國友], in Omi Province [近江國], present day Shiga prefecture. Kunitomo was famous for the production of firearms during the Sengoku-jidai, which suggests that Hideyoshi considered Nomura Naotaka to be a man worthy of considerable trust; and, given Hideyoshi’s passion for chanoyu (which was shared by his entire court), it is logical to conclude that Naotaka, too, would have cultivated an interest in tea -- and so been an appropriate recipient of the densho in question**.

He participated, with Hideyoshi and Rikyū, in the Battle of Odawara, leading a contingent of Hideyoshi’s musketeers; and at the Battle of Sekigahara, he fought on the side of Hideyoshi’s heir, Hidenori, and Ishida Mitsunari. Naotaka disappears from history after that battle, though the exact year in which he died, or the circumstances of his death, are unknown.

In the Rikyū Daijiten [利休大事典] (Tankōsha, 1989), a similar text is reproduced under the name Tenshō 9-nen ki-mei no densho [天正九年記銘の傳書]††. __________ *Tenshō ku[-nen] mi no ku-gatsu kichi-nichi [天正九 巳ノ九月吉日].

Other copies of the document date it to Tenshō 13 [天正十三], 1585, which would establish Nomura Naotaka firmly in Hideyoshi’s court.

The original document appears to have been in an extremely poor state of preservation when it was inspected by Suzuki Keiichi, which is why he copied the drawings, and much of the text, from later copies of the densho.

†The first historical mention of Nomura Naotaka is dated to sometime in 1570, at which time he was already a military man of some standing (suggesting he was firmly in his middle years).

The last puts him at Sekigahara, in the ranks of Ishida Mitsunari’s Western Army, though the implication is that he survived the battle and the immediate fallout that rained down on the more prominent members of the losing side.

‡The name Sōkaku would have been a religious name, of the sort used in the context of chanoyu, while the surviving information paints Naotaka in an exclusively military context, with the only side note being that he retired from public affairs and became nyūdō toward the end of his life (though the actual name that he assumed in his retirement has not been recorded -- he is referred to only as Higo-nyūdō [肥後入道], which, of course, was simply a reference to his having served as governor of Higo province, in west-central Kyūshū).

**The Nomura Sokaku-ate no densho has a certain focus on practices that might best be associated with the larger rooms, rooms such as Hideyoshi and his courtiers might be received on formal occasions -- a class of sahō [作法] that a courtier would be required to master. Since nothing that is known about Naotaka would lead us to believe that he and Hideyoshi were on intimate terms (and so would have reason to enjoy chanoyu in the small room setting), Rikyū’s focus on the more formal settings is completely understandable.

††This appears to be a generic copy of the densho from Rikyū’s personal archive. (It appears that Rikyū, perhaps because of his dyslexia over the Japanese language, wrote a basic draft of each of his densho first, which he then personalized before sending a copy to each of the disciples who had requested it -- and this Tenshō 9-nen ki-mei no densho was the document from which Rikyū adapted the text of his Nomura Sokaku-ate no densho.)

Both versions of this densho were translated earlier in this blog.

⁵Hidari-ba [左羽] is more usually read hidari-bane. Hidari-ba was probably used by Jōō because he needed a word with four syllables.

Feathers of this sort are widest on the left side of the rachis.

⁶Ginmi-suru [吟味する] means to examine closely, scrutinize.

⁷Kōgō [香箱] could also be read kō-bako (without any change to the syllabic count of the line). Both kanji-compounds (and pronunciations) were used interchangeably during the sixteenth century.

⁸Kōgō no kan no [香箱のくわんの]: this use of the particle no [の] is similar to using the particle ga [が] (which indicates the subject of the verb), albeit in the context of a subordinate phrase. In other words, both of these items (kōgō, kan) are subjects, albeit subordinate to the habōki (since that is the subject of the verbs okaba [をかば = 置かば] and oke [をけ = 置け], and to which the text of the shimo-no-ku [下の句], refers).

⁹The verb oke [をけ = 置け] is a command, indicating that the host must look carefully to ascertain the kind of habōki he is using before arranging the kōgo or kan with it.

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator.

To contribute, please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

❖ As the international exchange rate continues to collapse, your help is even more necessary than heretofore, since this blog is my only source of income. Please donate, if you can.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Constitution review: INC proposes creation of 2 additional Ijaw states

By Deborah Coker The Ijaw National Congress (INC) worldwide has proposed the creation of two additional Ijaw States. The proposed states the INC said should be carved out from Edo, Delta, Ondo, Bayelsa, Rivers, Cross River and Akwa Ibom. Prof. Benjamin Okaba, Global President, INC, made the proposal in his memorandum at the National Assembly Constitution Review Public hearing for South South…

0 notes

Text

Fubara Is Free To Join APC – Ijaw Nation President

The President of the Ijaw Nation, Professor Benjamin Okaba, has said there is nothing unusual if Rivers State Governor Siminalayi Fubara decides to leave the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) and join the All Progressives Congress (APC), especially if it helps settle the ongoing political tension in the state. He made this known on Thursday while speaking on a television programme shortly after…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Pa Edwin Clark lived for others - Goodluck Jonathan

…Diri, Dickson, PANDEF, INC, IYC also pay tributes…Bayelsa Government to immortalise late Ijaw leader Prominent leaders from the Ijaw ethnic nationality, including former President Goodluck Jonathan, Bayelsa State Governor, Senator Douye Diri, his predecessor, Senator Seriake Dickson and President, Ijaw National Congress (INC), Prof. Benjamin Okaba among others, on Monday, paid tributes…

0 notes

Text

How The Best Auto Body Shops Differ From The Others

What Sets Estes Collision Repair Apart From The Other Collision Repair Shops

Estes Collision, a premier collision repair shop in Miami, OK, provides high-quality auto body repair services, setting itself apart from the competition. With a steadfast commitment to quality, customer satisfaction, and state-of-the-art technology, Estes Collision has become a trusted name in the industry. This article gives an overview of what the best auto body shops do to differentiate themselves from the others.

Experience & Expertise

Estes Collision stands out as a collision repair shop due to its extensive experience and expertise. Founded by Billie Estes, an industry professional since 2007, the shop has been providing top-notch collision repair services since 2015. The team at Estes Collision is composed of highly skilled technicians who bring years of experience to every repair job. Their depth of knowledge ensures that each vehicle is restored to its pre-accident condition with precision and care.

Trained And Skilled Technicians

The backbone of any reputable auto body shop is its technicians. At Estes Collision, the technicians are not only trained but also continuously updated on the latest repair techniques and technologies. This ongoing education ensures that every auto body repair is performed to the highest industry standards. Skilled technicians are adept at diagnosing and addressing both visible and underlying issues, ensuring comprehensive and effective repairs.

Latest Technology, Equipment, And Facility

To deliver the best auto body repair services, Estes Collision invests in the latest technology and equipment. They follow OEM procedures. The shop is equipped with advanced diagnostic tools, computerized paint-matching systems, and modern repair equipment. These resources enable technicians to perform precise and efficient repairs, ensuring vehicles are restored to their original condition. Estes Collision is expanding with a new, cutting-edge facility expected to be completed in 2025, further enhancing its capabilities.

Focus On Customer Experience And Satisfaction

Exceptional customer service is a cornerstone of Estes Collision. From the moment customers walk through the door, they are met with personalized service tailored to their unique needs. The friendly and knowledgeable staff guides customers through the repair process, providing clear explanations and accurate estimates. This dedication to customer satisfaction ensures a smooth and stress-free experience, building long-lasting relationships based on trust and reliability.

Credentials

Any affiliations with manufacturers or industry groups can indicate a commitment to quality and adherence to specific repair standards. Estes Collision is a member of the Oklahoma Auto Body Association (OKABA). They uphold the highest standards of quality and professionalism in the industry.

Clear Communication

Transparent communication is key to a positive customer experience. Estes Collision prioritizes keeping clients informed throughout the collision repair process. From detailed explanations of necessary repairs to regular updates on the progress, the shop ensures customers are always in the loop. This clear and honest communication helps alleviate concerns and build confidence in the repair process.

Transparent Cost Estimates And Warranty

At Estes Collision, transparency extends to cost estimates and warranties. The shop provides detailed and accurate estimates before any work begins, ensuring customers understand all associated costs upfront. There are no hidden fees, and the clear breakdown of expenses builds trust. Furthermore, Estes Collision stands by the quality of its work with a limited lifetime warranty for vehicles owned by customers, providing them with peace of mind.

Flexibility Of Working With Insurance Providers

Dealing with insurance claims can be a hassle, but Estes Collision simplifies the process by working seamlessly with all major insurance providers except AllState. The shop assists with every step of the insurance claim process, from helping file the claim to communicating with the insurance provider. This flexibility ensures a smooth and efficient collision repair in Miami, OK, minimizing out-of-pocket expenses for customers.

Estes Collision, The Auto Body Shop In Miami, OK, You Can Trust

Choosing the right auto body shop is crucial for ensuring the safety, performance, and appearance of your vehicle. Estes Collision, with its skilled technicians, state-of-the-art equipment, and commitment to customer satisfaction, stands out as a trusted auto body shop in Miami, OK. Experience the difference that exceptional service and expertise can make. Contact Estes Collision at (918) 542 6699 or [email protected], or visit their shop. Trust Estes Collision, for all your auto body repair needs, and let them restore your vehicle to its original condition with the care and precision it deserves.

Original Source: https://estescollision.com/all-auto-body-shops-are-not-the-same/

0 notes

Text

INC support staff eulogies Benjamin Okaba on his 62 birthday

OFFICIAL BIRTHDAY MESSAGE To Our Visionary Leader and Exceptional Boss, Prof. Benjamin Ogele Okaba, President, Ijaw National Congress On the occasion of your birthday, we, the INC Support Staff, Office of the President, extend our heartfelt congratulations and best wishes. Your exemplary leadership, marked by uprightness, truth, and justice, has been a shining example to us all. As the voice of…

0 notes

Text

INC President Benjamin Okaba Shares Hope For a Better Niger Delta, Felicitates Ijaw People On Christmas Celebration

The President of Ijaw National Congress INC Professor Benjamin Okaba has congratulated Ijaw people and Nigerians at large for making it to the last month of the year 2024 and most importantly celebrating Christmas amidst the economic challenges of the nation. The Frontline Ijaw leader, Prof Okaba in a statement urged Ijaws to celebrate the yuletide with renewed commitment to development and…

#INC President Benjamin Okaba Shares Hope For a Better Niger Delta#Felicitates Ijaw People On Christmas Celebration

0 notes

Text

Dapatkan Stiker Hologram Berkualitas, Siap Kirim Ke Kabupaten Merauke

Dapatkan Stiker Hologram Berkualitas, Siap Kirim ke Kabupaten Merauke Untuk masyarakat Kabupaten Merauke, kini Anda dapat dengan mudah mendapatkan stiker hologram berkualitas tinggi. Kami melayani pengiriman ke seluruh kecamatan dan kelurahan di Merauke, termasuk: Merauke Tanah Miring Kurik Semangga Jagebob Lampu Satu Samkai Salor Ngurumbun Okaba Erambu Anda juga dapat menikmati layanan bayar…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

PAP: INC Expresses Satisfaction In Otuaro’s Administration, Says Ijaw Nation Is Proud Of Him

By Freeborn Abraye The Presidential Amnesty Programme (PAP) Administrator, Dr. Dennis Otuaro, has received praise from the national leadership of the Ijaw National Congress (INC) for his creative leadership. This was said by Prof. Benjamin Okaba, President of the INC, on Thursday at the PAP Office in Abuja while leading a delegation from the leading Ijaw socio-cultural organization to visit…

0 notes

Text

The Chanoyu Hyaku-shu [茶湯百首], Part II: Poem 44.

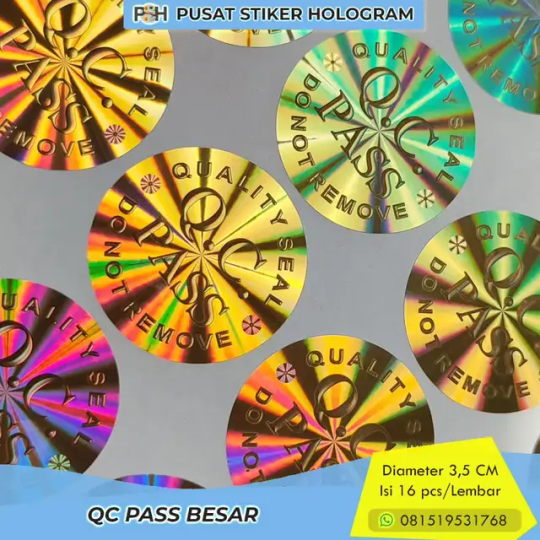

〽 Sumi tsugaba gotoku hasamu-na jū-mon-ji en wo kirasu-na tsuri-ai wo mi yo

[炭次がば五德挾むな十文字 緣を切らすな釣合を見よ].

“If [one is] adding charcoal, [two pieces should] not pinch [a leg of] the gotoku, nor [overlap to form] a cross or project beyond the perimeter¹; and [the distribution of the charcoal] should appear well-balanced.”

The first several points that Jōō makes -- that two pieces of charcoal should not pinch the leg of the gotoku, nor form a cross, nor extend beyond the perimeter of the fire² -- are also mentioned in the Rikyū sanjū-go-jō ken-ki [利休三十五條嫌忌] (which was translated earlier in this series³), suggesting that they were part of the traditional teachings that had been codified during the first half of the sixteenth century.

The final admonition (that the host should make sure that the distribution of charcoal is well-balanced) is important because it will help to prevent one side of the fire from becoming too hot⁴ -- which could cause the fire to burn out on that side before the service of tea had been concluded.

There are two different versions of the first line of the kami-no-ku [上の句]. Jōō’s version begins sumi okaba [炭置かば], which means “if [one is] placing the charcoal....” The later versions⁵ (including the one found in Hosokawa Sansai’s Kyūshū manuscript) begin with the words sumi tsugaba [炭次がば] -- meaning “if [one is] adding charcoal....”

As these both describe precisely the same series of actions, there is no real difference between any of the versions.

_________________________

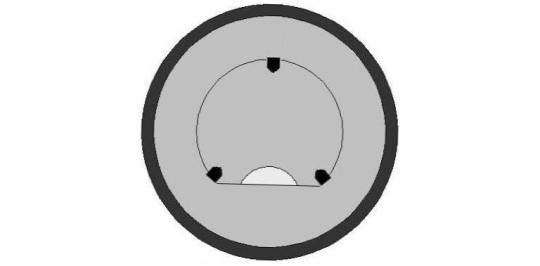

¹The perimeter (en [緣], which is a contracted form of enishi [緣]) of the fire was originally determined by the rim of the kimen-buro (which was mirrored by the shape of the ashes). When Jōō first began to use the ro, he sculpted the hai-gata to serve as his guide. And after he introduced the use of a gotoku* (as equivalent to the rim of the kimen-buro), the perimeter was thereafter defined by the ring of the gotoku.

While the ring is now buried in the ash (and so has to be guessed at by the host), when Jōō first began to use the gotoku, it was oriented with the ring uppermost (this is why the tops of the three legs on antique gotoku are frequently shaped like broad feet that are often etched with parallel lines that act like skid guards, to give the feet traction so the gotoku does not slip on the ash when the kama is rested on top). It, therefore, physically enclosed the space where the charcoal was to be arranged, much as does a fence around a flower-garden.

This arrangement of the gotoku was based on the way that a kiri-kake gama rests on the rim of a kimen-buro (since this was the only precedent available for Jōō to adopt at that time).

Originally the ring was always a complete circle, regardless of whether the gotoku was going to be placed in the ro, or (apparently only later) in a furo.

The reason why the third of the ring in front was cut away on gotoku intended for use in a furo was something suggested by Sen no Dōan, following his creation of the Dōan-buro [道安風爐] (all of which occurred when he was a teenager†).

Dōan made the Dōan-buro from an old lacquered clay mayu-buro [眉風爐] (mayu [眉] means “eyebrow,” and refers to the section of rim that extends across the top of the hi-mado, as can be seen in the left drawing)‡ that had been thrown away (some accounts claim that he brought it home from the local dump). Regardless of its source**, the rim of this furo was broken above the hi-mado, which is why it could no longer be used for chanoyu. Dōan cut away the remainder of the rim††, extending the sides of the himado up to the rim (as shown in the right sketch). After relacquering the furo, he went to place the gotoku in it as usual, but the third of the ring extending across the front was disquieting (since it seemed as if it would potentially interfere with the sumi-temae); so he cut it away, thereby creating what we refer to today as the furo-yō no gotoku [風爐用の五德]‡‡. ___________ *This object was originally called a ko-taku [火卓], which can also be pronounced ko-joku.

The name gotoku [五德] (which means “five virtues,” perhaps as a play on both the word ko-joku and jittoku [十德], the latter being the name for a monk’s black-gauze over-garment, which was sewn from ten pieces of cloth) seems to have been coined by Sen no Dōan, after he modified his gotoku by cutting off one section of the ring (so it could be used in his Dōan-buro, as described in this footnote): the three legs, plus the remaining two sections of the ring means the gotoku is composed of five pieces.

†Dōan was born in 1544, around the time of Rikyū’s departure for the continent; and he likely created the Dōan-buro at some point during the 1560s, while Rikyū was working on rebuilding the family fortunes through the sale of the chawan and other objects that he had brought back from Korea.

‡As a result of the continuing trade embargo with the continent during the first half of the sixteenth century, the locally produced mayu-buro had largely replaced the (imported) bronze kimen-buro [鬼面風爐] and Chōsen-buro [朝鮮風爐] as the preferred furo for use on the daisu.

**The most common way that the rim above the mayu would break is through mishandling -- because someone had attempted to pick the furo up by holding it with the fingers through the hi-mado. That it was broken, therefore, suggests that the person handling it had been extremely negligent. Finding the broken furo in the dump would exculpate Dōan (and anyone else in the household) from blame -- and this may be why this detail was often emphasized in retellings of this story.

††This would have been easy to do, since this kind of furo was made of very low-fired clay (indeed, the lacquer is necessary to protect the clay, since it is so low-fired that it can begin to disintegrate if water drips onto it), which is easily cut with an ordinary handsaw.

In those days, chajin also made their own mae-gawarake [前土器] (the semi-circular tile that is placed in the front of the furo, to protect from sparks shooting out of the kindling charcoal), by cutting off part of the edge of the low-fired clay sake-saucers that were sold for use in Shintō rituals (after use these saucers were thrown into a bucket of water, where they would eventually dissolve into clay again). These saucers were made by the same craftsmen who made the clay furo, and were fired in the same way, so the idea of cutting low-fired clay objects with a saw hardly originated with Dōan -- indeed, the necessary skill-set would have been commonplace among the chajin of that day.

Several years ago I witnessed the opening of the wooden box in which an old clay furo of this sort had been stored (the box had not been opened for many years, since the chajin of that house had died without a successor). Water had somehow dripped onto the box, and the furo had completely deteriorated into a mound of clay on that side, despite its having been painted with lacquer.

Modern clay furo are fired at higher temperatures to prevent this kind of thing from happening. (In the old days, clay furo were used only until the lacquer began to crack on the inside, and then discarded. Those made nowadays, however, are sent back to the craftsman, and the old coat of lacquer is burned off in a kiln before they are polished and re-lacquered again.)

‡‡The idea of turning the gotoku upside-down (so the ring would be buried in the ash) was proposed by Rikyū, in 1582 or 1583, so that the small unryū-gama could be used inside the large kimen-buro (the kiri-kake gama for which had been lost in the fire at the Honnō-ji, while the rim of this iron furo was cracked above the himado when Mori Ranmaru threw it against the wall in order to start the fire that would consume the shoin, in order to prevent Akechi Mitsuhide from collecting and displaying Nobunaga’s head).

Because the rim of the furo was no longer strong enough to support the weight of a kama, Rikyū made the cylindrical unryū-gama the diameter of the original kama’s mouth, with the intention of placing the kama on a gotoku. But if the gotoku was oriented as usual -- with the ring uppermost, the ring would block the flow of air through the furo; so he came up with the idea of placing the gotoku upside-down, with the kama standing on the feet of the gotoku, which would allow hot air to rise freely all around the sides of the kama.

Since arranging the gotoku in this way allowed for virtually all of the kama that had theretofore been usable only when suspended from the ceiling (and so almost always had been limited to being used with the ro), it was adopted so widely that, over the course of the Edo period, the idea that the gotoku had originally been used with the ring uppermost was completely forgotten.

As for this original Dōan-buro, it is said that Rikyū held it should be used only in the most ultra-wabi of settings. To emphasize this fact, during the sumi-temae, the habōki was supposed to be a single feather, originally without a handle (ordinary habōki are typically made from three feathers, and have either a wooden handle, or one made from a folded bamboo sheath tied with cord). The rest of the utensils were also expected to be just as rustic as the habōki.

The mind behind this approach to chanoyu remained a feature of Dōan’s style for the rest of his life (and culminated in his creation of the Dōan-gakkoi [道安圍い] style of room). The reader should note that the doorway between the host and his guests is rendered as a kayoi-guchi [通い口], meaning a service entrance -- a door through which things are passed to the guests without otherwise disturbing them.

The above Dōan-gakkoi is found in the Yodomi-no-seki [澱看席] in the Saiō-in [西翁院] of the (Jōdo-shū [淨土宗] affiliated) Konkaikōmyō-ji [金戒光明寺] in Kyōto. (In this kind of room -- and contrary to what is seen in some modern photos -- Dōan, adhering to his father’s teachings, would have placed the furo on top of the lid of the ro, as in an ordinary mukō-giri room.)

While today it is usually taught that the host should slide the door open immediately before the sō-rei [総礼] (at the beginning of the koicha-temae), so the guests can watch his temae, Dōan is said to have kept it closed until the bowl of koicha was prepared -- after which he opened the door and offered the tea to the guests. Dōan seems to have taken his inspiration from the earlier o-chanoyu-dana [御茶湯棚], with the self-effacing humility that this inspires as the focus of his practice -- which, in turn, was based on the fact that the original kind of chanoyu was the offering of a bowl of tea to the Buddha, something that was done between the monk and the representation of the Buddha, with no other person present.

²Rather than en wo kirasu-na [緣を切らすな], which means (should) not project beyond the perimeter (of the grouping of charcoal), the Rikyū sanjū-go-jō ken-ki [利休三十五條嫌忌] alludes to this idea by way of hikozuri-basami [引すり挾み], which refers to the image of a formal court train that trails behind the rest of the wearer’s garments. While the image is different, the ultimate meaning, with regard to the arrangement of the charcoal (and the fact that no piece should project outward beyond the perimeter of the group), is the same.

³Please refer to the post entitled The Chanoyu Hyaku-shu [茶湯百首], Part I: Poem 21. The Rikyū sanjū-go-jō ken-ki [利休三十五條嫌忌] are translated, in full, in the appendix at the end of that post. The URL is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/750434095968010240/the-chanoyu-hyaku-shu-%E8%8C%B6%E6%B9%AF%E7%99%BE%E9%A6%96-part-i-poem-21

In the version of the sanjū-go-jō ken-ki translated there, the points dealing with the charcoal are numbered 31 to 35. In addition to the rejection of situations in which two pieces of charcoal pinch the leg of the gotoku, form a cross, or extend beyond the perimeter of the fire, this list also includes chō-ji [丁字], which means placing two pieces of charcoal so that they form a “T” shape. Since it is similar to jū-mon-ji [十文字], it was probably left out of the poem in the interests of syllabic structure -- thus allowing Jōō to cover everything he wanted to say about the charcoal in a single verse.

⁴Which could cause the lacquer coating on clay furo to crack on that side, rendering the furo useless*. ___________ *Not because it necessarily impacts the furo’s ability to perform its proper function, but because it is inauspicious. This is why damaged utensils were not supposed to be used (during that period).

The use of such “distressed” pieces was discouraged until the early Edo period, when the focus began to reflect economic considerations.

It might be good to add that the way the ashes were arranged that was preferred in Jōō’s and Rikyū’s day was very different from that advocated by many of the modern schools. Their hai-gata was shaped like what is shown below, and was relatively deep (the ash rose half way up the legs of the gotoku, or more).

This way of arranging the ashes protected the lacquered sides of the furo. The modern ni-mon-ji [二文字] ash-shape (and its “artistic” variants, where the host recreates the effect of mountains and valleys within the furo) focuses the heat of the fire on the left and right sides of the furo, invariably causing the lacquer to crack after not many uses. As a result, many professional chajin in Japan have to send their furo back to be relacquered at the end of every furo season. (Using a hotplate-style heating system helps, but does not completely alleviate the problem -- and, of course, it eliminates the sumi-temae and all of the teachings connected with that.)

Jōō’s and Rikyū’s hai-gata are described (and illustrated) more fully in the post entitled The Three Hundred Lines of Chanoyu (Lines 51 - 60), under line 57. The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/26906281437/the-three-hundred-lines-of-chanoyu-lines-51

⁵Somewhat curiously, the version found in the collection of the Hundred Poems that was given to Katagiri Sadamasa during his period of study (with the Sen family) agrees with Jōō’s version. This suggests that the Sen family altered the contents of the collection preserved in their archives in deference to the version of this poem that was being disseminated by Hosokawa Sansai -- perhaps because, since Sansai was the last surviving of Rikyū’s personal disciples, they decided that his version must be “more accurate” than the one that they had acquired previously. But the uncertain nature of Sansai’s very influential recollections (he was pressed to write his teachings down during the last years of his life) can be easily seen when his manuscript is compared with Rikyū’s own densho.

Indeed -- and most unfortunately -- it is not infrequently the case that Sansai declares as correct something that is the polar opposite of Rikyū’s actual teaching (as supported by Rikyū’s own densho). The likely cause for why this version was given credence was because of another misunderstanding of Rikyū’s relationship to Sansai: Hosokawa Yūsai [細川幽齋; 1534 ~ 1610], Sansai’s father, was Rikyū’s great friend, and the connection between the two houses may be found there. The Sen family, nevertheless, interpreted Sansai’s visit to the bank of the Yodogawa, to bid Rikyū farewell as he was being sent back to Sakai (where he had been ordered to commit seppuku), as a sign, on a purely personal level, of the intimacy between these two men. But, in fact, it appears that Yūsai had ordered his son to do this -- in his stead -- because he would then be in a position to defend his house, and his son, against Hideyoshi’s potential anger, should their lord take offense at this gesture; whereas Yūsai would have been powerless to do anything if, having gone himself to say goodbye to his old friend, Hideyoshi had then fallen into a rage.

During the last eight or nine years of Rikyū’s life, Sansai was increasingly busy with affairs of state, so the time available for him to study with Rikyū would have been truncated to the point where, as we see in his writings, he ended up completely misinterpreting many of the things Rikyū sought to teach him* -- and so became guilty of misrepresenting them (whether deliberately or not†) to posterity. Nevertheless, on account of the respect and affection in which the Sen family held Sansai, his pronouncements were deemed strong enough to cause them to completely rethink the teachings of Rikyū that had come to them from other sources. ___________ *One commonly mentioned difference regards the way to pick up the natsume and wipe it with the fukusa, as opposed to the way to do the same with the nakatsugi. In his writings, Sansai completely reverses Rikyū‘s teachings on these matters.

†Sansai’s writings on chanoyu date from the period when the daimyō who were involved with chanoyu were becoming increasingly restive, as the conflict between those of Rikyū’s own teachings that were preserved in their family archives, and the teachings proselytized by the Sen family, came to diverge farther and farther. But whether he wrote things that would knowingly differ from the Sen family’s teachings, or did this inadvertently (as a result of his misremembering things that had been said to him by Rikyū), is unclear.

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator. Please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Warri ward delineation: INEC acting within constitution -INC

By Deborah Coker The Ijaw National Congress (INC) worldwide says the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) is acting within its constitutional mandate in the Warri ward delineation exercise. Prof. Benjamin Okaba, Global President of INC worldwide said this in an interview with the News Agency of Nigeria (NAN), in Abuja on Saturday. Okaba was reacting to the call for the cancellation of…

0 notes

Text

"Coalition of Indigenous Ethnic Nationalities Calls for Immediate Restructuring of Nigeria"

The Coalition of Indigenous Ethnic Nationalities (CIEN) has urgently called for the restructuring of Nigeria in light of the severe political and socio-economic issues threatening the nation’s unity. In a statement issued on Thursday in Kaduna, and jointly signed by Chairman Prof. Benjamin Okaba, Co-Chairman Mr. Timothy B. Gandu, and Secretary Mr. Nubari Saatah, the group highlighted the pressing…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Rivers political crisis: Ijaw group urges Wike to make peace with Fubara

The Ijaw National Congress Worldwide has urged Rivers State’s immediate past governor, Nyesom Wike, to make peace with Governor Siminialayi Fubara for peace and prosperity. The group, which expressed its discontent with the state’s political problems, particularly between Fubara and his predecessor, stated that it would always be on the side of truth and good administration. This was said in a statement released by the group’s President, Prof Benjamin Okaba, and made available to newsmen in Akure, Ondo State, on Sunday. In the statement, the group commended the people of Rivers State for standing up to the alleged planned impeachment of Fubara and encouraged Wike not to destabilize the state’s existing administration. The statement read, “We urgently call on all political players in Rivers State to play their duty to their constituents and forthwith cease from any further acts capable of slurring the sanctity of the office, institution, and person of the Governor of all Rivers people. “We specifically appeal to Chief Nyesom Wike, to retrace his steps from stoking division of any sort against the government of the day under the guise of protecting his ‘structure’. The political structure to which he refers should not be rolled up with the structure of the government of Governor Fubara as one entity under anyone’s thumb.” Read the full article

0 notes