#nonrivalrous

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

weird it's almost like information is nonrivalrous 🤔

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tech a la carte

“Oblique Strategies” is Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s deck of 100+ cards, each with a sentence of gnomic advice. They inspired Roxy Music, David Bowie, Talking Heads and Devo. My favorite? “Be the first person to not do something that no one else has ever not done before.”

Why that one? Because it challenges us to imagine how something that we perceive as unitary and indivisible might be decomposed into smaller units. It’s a challenge to the notion that one must “take the bad with the good.” What if we could just get rid of “the bad?”

Back in 1998, John Kelsey and Bruce Schneier proposed the “Street Performer Protocol” as a means of funding nonrivalrous, nonexcludable projects — that is, things that can be infinitely reproduced at effectively no cost, and whose reproduction can’t be easily prevented: things like software and digital books, music, and videos.

https://www.schneier.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/paper-street-performer.pdf

As the name implies, the Street Performer Protocol is inspired by the tactics of street performers like magicians, jugglers and acrobats, whose work is nonrivalrous (lots of people can watch the performance without impacting others’ viewing) and nonexcludable (performers can’t limit the audience to people who’ll put money in their hats).

A hypothetical performer draws a crowd with a series of feats of escalating daring and difficulty, building towards a peak. Then the performer halts the show and announces, “You’ve seen how skilled I am, but you haven’t seen my greatest trick. I will perform that trick once there is $50 in my hat. I don’t care how many of you pay, and I can’t make you pay, and if $50 doesn’t land in my hat, I’m going home.”

The Street Performer Protocol is a digital version of this. After producing a bunch of work to attract an audience, a creator announces, “I have some very ambitious song or book or movie I’d like to make. I will make it once there is $1000 in this escrow account, and then release it for all to enjoy. You know I won’t run away with this cash because it’s being held by a trusted third party until I deliver it.”

The Street Performer Protocol arrived at the dawn on the copyright wars (it came out a year before Napster), and in the years that followed, lots of people tried to create a functional Street Performer Protocol service. These all foundered on the same point: the escrow account. A creator who raised $1000 to (say) write a book needed that $1000 to pay their rent while their wrote, but they only got it after they were finished.

The escrow account was deemed necessary to prevent scammers from poisoning the well: if funders were convinced that putting up money for a project would mostly enrich con-artists, then legitimate creators wouldn’t be able to attract funders.

This was a deadlock. Escrow and crowdfunding were inseparable. Doing one without the other courted disaster. Then, 11 years after the Street Performer Protocol was proposed, three technologists tried being “the first person to not do what no one else had ever tried not doing.”

They founded Kickstarter. Kickstarter is a Street Performer Protocol without escrow. Once a project reaches its funding goal, the founder is guaranteed their payout. This meant that a lot of projects raised a lot of money and then never delivered, either because they were run by con artists or by unrealistic dreamers.

Kickstarter was a bet that the excitement at the projects that did happen would outweigh the disappointment and anger at the projects that didn’t. Instead of escrowing funds until delivery, they escrowed them until a funding threshold was met — if you said you needed $50k to make a short film and your backers only pledged $2k, you got nothing.

Once Kickstarter showed that the indivisible prix fixe Street Performer Protocol could be decomposed into an a la carte menu, rivals sprang up to see what else they could remove. Indiegogo took away the threshold escrow — no matter how much you raised, you got paid. Patreon created rolling pledges, first based on the number of works you produced, then on a monthly schedule.

It’s business-model Jenga: removing one block at a time until the system collapses. Removing too many blocks produces hardship and misery (cough Pledgemusic cough). But the insistence that no blocks can be removed leads to stalemate — the decade-plus interregnum between the Street Performer Protocol paper and Kickstarter.

Even better than businesses “not doing the thing that no one has ever tried not doing before” is when people don’t do “the thing that no one has ever tried not doing before.”

Remember pop-up ads? Once upon a time, most web-pages spawned whole flocks of pop-up ads, each more obnoxious than the rest. Some popups were one pixel by one pixel, others ran away from your cursor, others autoplayed music. Some did all three!

How did we get rid of pop-ups? It wasn’t by banning them — it was by blocking them. Browser vendors sought out competitive advantages by adding pop-up blocking to their offerings: first Opera, then Mozilla, and, finally, Internet Explorer.

There was a period of skirmishing here, where pop-up designers created anti-block pop-ups that circumvented the blockers, but eventually they threw in the towel. Your current browser probably has a pop-up blocker enabled by default, but if you turn it off, you won’t be inundated with pop-ups. They’re gone.

Once advertisers realized that most users wouldn’t see pop-ups, they stopped demanding that publishers include pop-ups. Web users, collaborating with browser designers, killed pop-ups more thoroughly than any regulation could have. Rather than banning pop-ups they hunted them to extinction.

Today, pop-up blockers have been replaced by ad-blockers, which a quarter of internet users have installed (Doc Searls calls it “the biggest boycott in human history”). As with pop-ups, internet users are removing the ad Jenga block and seeing whether things fall over:

https://blogs.harvard.edu/doc/2015/09/28/beyond-ad-blocking-the-biggest-boycott-in-human-history/

And, as with crowdfunding, different actors are removing different blocks. Privacy Badger, a project from EFF, doesn’t block ads, but it does block trackers.

https://privacybadger.org/

Proponents of commercial surveillance like to call their products a bargain: “in exchange for this much website, we take this much privacy.” But it’s a curious kind of bargain: visiting a website is like walking into a store where the merchant gets to take as much money out of your wallet as they like, without telling you in advance, and never has to give it back.

Ad- and tracker-blocking can be thought of as a means of bargaining back. When the website says, “To see this content, you must give us all your privacy,” blockers let you respond: “How about ‘Nah’?”

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/07/adblocking-how-about-nah

Tech platforms don’t like this bargaining, of course, but they couch their objections in the language of impossibility, not choice. When we say, “Give us a search-engine that doesn’t spy on us,” Google responds by saying that this is inconceivable, like asking for a way to go for a swim without getting wet.

But it’s obviously possible to run a non-surveilling search-engine. We know that because Google only started spying on us in 2004, six years after its founding and long after it became the most used search engine online:

https://evgenverzun.com/google-and-user-privacy-the-evolution-of-a-20-year-relationship/

No one came down off a mountaintop, intoning “Larry! Sergey! Thou shalt stop rotating thine logfiles and begin mining them for actionable intelligence.” Spying was a late-breaking addition to Google Search, and what can be added can be removed.

Likewise Facebook. A lot of us have forgotten this, but until 2008, Facebook billed itself as the privacy-friendly alternative to MySpace and promised it would never spy on its users, as is beautifully documented in Dina Srinivasan’s must-read “The Antitrust Case Against Facebook”:

https://lawcat.berkeley.edu/record/1128876?ln=en

Today, Facebook would like us to think that there is no way to talk to your friends without also letting Mark Zuckerberg peel you open from asshole to appetite. It’s bullshit. Web publishing doesn’t require pop-ups. Social media doesn’t require surveillance. These are choices, not foundations.

With both Facebook and Twitter failing, we’re at a crossroads. We’re being told that we can’t get the benefits they delivered — the friendships, debates, transactions, support, and connection — without the increasingly desperate anti-features they’re trying to cram down our throats:

https://doctorow.medium.com/how-to-leave-dying-social-media-platforms-9fc550fe5abf

But a Facebook that you can leave behind without losing contact with your friends isn’t just a fantasy — it’s a technical possibility. Regulators could force Facebook to expose an API to the Fediverse so you could leave the platform but still connect with the people who want to connect with you:

https://www.eff.org/interoperablefacebook

Or reverse-engineering guerrilla hackers could accomplish the same thing with bots and scrapers and alternative clients (AKA “Adversarial Interoperability” or “Competitive Compatbility” or “comcom”):

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/10/adversarial-interoperability

Or we could do both.

Elon Musk now claims absolute dominion over Twitter. That’s only true to the extent that the courts let him exclude rivals who create interoperable add-ons that let you alter the service to suit your needs; or to the extent that regulators choose not to order the service to expose APIs to make life better for users.

We don’t have to give up Twitter, nor do we have to remain on Musk’s terms. As Skylar Hill writes writes, we can embrace “the anarchist philosophy of dual power; do the work to build better systems while the old ones still dominate, and it’ll be there for folks when the bad system finally collapses.”

https://mamot.fr/web/@[email protected]/109303911626298524

For decades, clueless lawmakers have made stupid demands of tech companies For example:

Create an encryption system that works when criminals are trying to steal your data, but stops working when cops want to execute a search-warrant, or

Create a copyright filter that automatically blocks infringement but not parody, fair use, or other legitimate activities.

When technologists insisted that these were impossible, the clueless lawmakers doubled down, shouting “NERD HARDER, NERDS!”

Today, tech barons are weaponizing these moments of idiocy by insisting that demands for privacy and interoperability are no different from the demands for working encryption with police backdoors. Don’t be fooled. Just because some demands are absurd, it doesn’t follow that all demands are absurd.

We can — we must — be the first ones to not do what no one else has ever thought of not doing before.

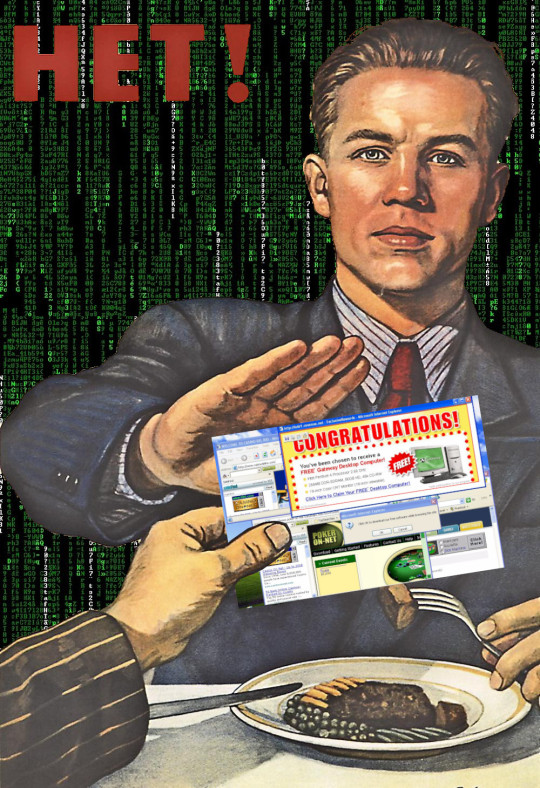

[Image ID: A remix of the iconic Soviet 'Nyet' anti-drinking poster. In this version, the background has been replaced by a Matrix 'code waterfall' effect and the main figure is refusing a proffered screen full of early-2000s pop-up ads.]

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adrian Vermeule has written a defense of common good constitutionalism, but his concept of "the common good" remains opaque to me.

The Common Good in Politics and Law In the classical account, a genuinely common good is a good that is unitary (“one in number”) and capable of being shared without being diminished. Thus it is inherently nonaggregative; it is not the summation of a number of private goods, no matter how great that number or how intense the preference for those goods may be. Consider the aim of a football team for victory, a unitary aim for all that requires the cooperation of all and that is not diminished by being shared. The victory of the team, as a team, cannot be reduced to the individual success of the players, even summed across all the players. In the classical theory, the ultimate genuinely common good of political life is the happiness or flourishing of the community, the well-ordered life in the polis. It is not that “private” happiness, or even the happiness of family life, is the real aim and the public realm is merely what supplies the lawful peace, justice, and stability needed to guarantee that private happiness. Rather, the highest felicity in the temporal sphere is itself the common life of the well-ordered community, which includes those other foundational goods but transcends them as well. [...] The common good, at least the civil or temporal common good, can be described in substantive terms in this way: (1) it is the structural political, economic and social conditions that allow communities to live in accordance with the precepts of justice, yielding (2) the injunction that all official action should be ordered to the community’s attainment of those precepts, subject to the understanding that (3) the common good is not the sum of individual goods, but the indivisible good of a community, a good that belongs jointly to all and severally to each.

Does anyone understand what Adrian is saying here?

I can understand why he wants to smuggle in a thick theory of the good, but what does all this Romish metaphysics mean? What work is it doing?

I am having trouble giving content to the basic terms here. Adrian seems to have constructed categories that can't hold much normative content or do much legitimation.

What kind of good is "unitary [and] nonaggregative" and "not the sum of individual goods, but the indivisible good of a community, a good that belongs jointly to all and severally to each"?

That seems to describe public goods, whose nonexcludability and nonrivalrousness make them "indivisible ... belong[ing] jointly to all and severally to each."

That can't be what Adrian means -- public goods are goods, not a unitary good; public goods exclude most of the work the modern state does; and public goods have no thick normative or prescriptive content -- but I don't know what he does mean.

I assume this extended definition works to keep out utilitarianism, individualism, and pluralism, but I have no sense of what is left when they've all been forced out.

Can anyone make sense of this?

32 notes

·

View notes

Quote

When Locke spoke of creating property by mixing our labour with the land, he had fallow land in mind. This is precisely not the nature of artistic and scientific creation, where the creator ‘mixes’ his ideas with those of others to create a new work. Think of the relationship between rock ’n’ roll and the blues, between Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and Baz Luhrmann’s, between older scientific theories and the newer ones that build on them. Knowledge and creative works are nonrivalrous, nondepletable goods subject to network effects. To control them like ‘tangible property’ is to reduce their social utility. The domain of the various bodies of law that make up ‘intellectual property’ is a very different kind of property, perhaps so different that it shouldn’t be understood as such.

The idea of intellectual property is nonsensical and pernicious

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Many different types of goods exist within our daily lives without realizing it! Below I'll show each type with a real-life example! First is the public good, which is parks. Parks are public goods because they are non-excludable, which means many people can enjoy them. And they are also nonrival because many people can enjoy the park without limiting someone else's enjoyment.Second, are common resources which are roads. Public roads are non-excludable because everyone can use the streets freely. However, they are rivalrous in consumption because someone else is having a less enjoyable experience using the streets. Traffic jams occur because there is a limited amount of space.Third an example of club goods is a subscription such as HBO Max. Hbo max is excludable because you need to pay to use it. However, it is nonrivalrous because multiple people can utilize HBO, and there is no set limitation of people that can use the subscription.Lastly, an example of private goods is a drink. My Philz coffee is rivalrous in consumption and excludable because no one can drink my coffee once I have bought it.

Helen Mateo (#12865135)

0 notes

Text

Economics of Camping & Routers

Name: Johnson Tat

School ID#: 20067605

Camping is one of my favorite hobbies that I used to do before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced many camping grounds to be closed to prevent and slow down the spread of the virus. Despite this, not every camping ground is closed and camping interest has actually increased due to the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many people to be quarantined and to work from home. This new ability to work from home has allowed many people to camp more often and work simultaneously. Without the need to be present at a specific location to do work, this allows for more flexible schedules and more time for other activities like camping. Another possible reason for this increased interest is due to the fact that many people want a break from being inside all day. The pandemic has made a lot of people realize the importance of nature and being outdoors has on our mental health.

The graph above illustrates what happens to the price and quantity demanded of camping grounds. As shown above, the supply of camping grounds has decreased due to many of them closing down due to COVID-19. The demand for camping ground spots has increased due to this renewed interest in camping caused partially by the pandemic. As a result, the equilibrium quantity has remained about the same while the price has increased. Because of this, it has been quite difficult to get a reservation at one of these camping grounds for a price I can afford.

These camping grounds are also an example of a club good. This is because it is nonrivalrous in consumption and excludable. It is excludable in that permits are often required for camping at many of these camping grounds or national parks. It is nonrivalrous in consumption because using a camping ground does not prevent another person from using it as well.

The demand for RVs has also increased dramatically due to this increased interest in camping. Some vendors have seen up to three times the number of demand for RVs than the previous year. As a result, prices for RVs have risen. This increased demand and price is reflected in the graph below.

While the demand for camping related goods is increasing, the demand for something else is also increasing: routers and internet service.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced hundreds of thousands of people into quarantine where they cannot leave their homes. Because people cannot just go outside to enjoy the activities that they used to enjoy, many people have to rely on the internet to do work or to entertain themselves. As a result of this, demand for electricity and routers increased.

The price elasticity of demand curve for electricity looks like a vertical line or close to one(illustrated below). This is because electricity is a necessary resource for thousands of people in order to function and be productive. It also does not have any close substitutes. Both of these attributes makes electricity an inelastic good. What this means is that even if the price is raised and we whine and complain about it, we are still willing to pay it because there is no other choice and is necessary.

There are negative externalities that come with increased electricity demand. As internet usage and electricity usage goes up, the amount of fossil fuels power companies have to burn to meet this increased demand of electricity creates tons and tons of carbon dioxide(CO2). This increased amount of CO2 traps more and more heat and causes global temperatures to rise, making it harder for plants, animals, and humans to survive. This evidently effects everyone living on Earth, including people who don’t even use electricity.

To correct the negative effects of this, the government can levy a tax on carbon emissions from plants which would bring the price up to the socially efficient price(P1 to P2). This money could be used to subsidize renewable energy technologies to correct or reduce the negative effects of carbon emissions.

To access the internet, I also needed a better router. Last quarter, I had to build a new ASUS router since my old router was giving me some issues. Before deciding on this router, I had to go through multiple different router brands in order to find the best one that suited my needs.

I had the choice between a Netgear router, a TP-Link router, and an ASUS router. In the end, I ended up choosing the ASUS router since it gave me the best performance for a decent price.

In comparison to the price elasticity of demand curve for electricity, the price elasticity of demand curve for routers is more horizontal(still a little vertical) and elastic as there are more substitutes for routers than for electricity in general. What this means is that routers are price sensitive and if the price for a specific router brand were to rise by a dollar, consumers would switch to a substitute router that is lower in price and would demand more of that.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 11 - Reflections

1. Think of an example of a Public Good (not a publicly provided good, but a Public Good using the definition from the chapter.) What are the costs of providing the good? What are the benefits? Is there another way to have the good provided? Did this chapter cause you to think of Public Goods differently? In what way?

- A public good has two key characteristics: it is nonexcludable and nonrivalrous. These features make it difficult for market producers to sell the good to individual consumers. Nonexcludable means that it is costly or impossible for one user to exclude others from using a good. Nonrivalrous means that when one person uses a good, it does not prevent others from using it.

Studying Economics definitely changed my perspective on looking at ordinary things in life. Therefore, something I have never thought of as in the definition of Public Good, and it definitely belongs in that category is a lighthouse. I was spending my summers during my childhood on an island, and there was nothing around but a lighthouse in front of my summer home. The ships passing by and using the benefit of the lighthouse haven’t paid anything for it, and also there is no limit on the number of vessels that can benefit from its existence at the same time.

0 notes

Text

Day #151

Today I started with a Math lesson on multiplying and dividing complex numbers in polar form. I started off with a video on dividing complex numbers in polar and exponential form. Then, I did a complex number multiplication visualization review in which I learned that the formula for multiplying complex numbers in their polar form is Z1*Z2=r1*r2[cos(theta1+theta2)+i sin(theta1 + theta2)]. I also learned that the formula for dividing complex numbers which is Z1/Z2=r1/r2[cos(theta1-theta2)+i sin(theta1-theta2)]. I then did a practice quiz on multiplying an dividing complex numbers in their polar form followed by a video on powers of complex numbers. When calculating the powers of complex numbers in their polar form, all you have to do is multiply the exponent by the module and theta. I then watched a few videos on De Moire’s theorem which I said above when I was articulating the formulas for multiplying and dividing complex numbers in their polar form. Next, I did a French lesson on Duolingo followed by a chemistry lesson, more on Entropy. As stated in the Second Law of Thermodynamics, any spontaneous process increases the disorder of the universe. In order for a process to be considered spontaneous, the reaction must not need any outside forces to act upon them in order to react. Entropy is very important to chemistry and is one of the main reasons why chemical reactions even occur. It can also help conclude how spontaneous a reaction is. When you plug it into the formula and the change in entropy from the products to the reactants is positive, then the reaction has entropy and therefore increases the disorder of our universe. Entropy is also a state function, meaning it doesn’t depend on the pathway it takes to get form the products to the reactants, it only matters what you get as a result of that process and if any outside forces where acted upon it in order to make it occur. In this video, I looked at an example of Barium Octahydrate and Ammonium Chloride, reacting spontaneously. If you put a beaker on a block of wood and in between the blacker and the wood, place a bit of water, at you react the Barium Octahydrate and the Ammonium Chloride, it sucks out any heat within a certain distance of them reacting and therefore freezes the beaker to the block of wood. If you put this into the Entropy formula, you will find that this reaction is entropic and that the reaction itself proves it to be true. I then took an environmental science class on the Green Revolution which was started in the 1940s by Norman Borlaug as he brought specially breed wheat to Mexico and other developing countries in order to reduce the amount of additional cultivation when one system is depleted. This had a great amount of positive results such as a tiger human pollution, less overcultivaiton, more food for a wider expanse of people etc,. BUT... this also had a tremendous amount of negative effects after industrial agriculture became abundantly popular and resulted in pollution, erosion, salinization, desertification, etc,. Also, as more monocultures are being used more, genetic variation is depleting in a time where genetic variation is needed. I then did a quick exercise followed by an hour long lunch. I then took an economics class on Public Goods which are non excludable and nonrivalrous and is a main reason why “Tragedy of the Commons” is even a thing! Next, I took a women's history class on Marian Anderson who was an African American singer that was the first member of the Metropolitan Opera Company and inspired many young, black singers to follow their dreams despite many racially skewed obstacles. Next, I took a grammar class on prepositions of space followed by reading the first chapter of “The Beauty Myth” which talks about beauty standard around the world developed by the Patriarchy that women feel they have to live up to to be worthy. Whether that be eating disorders, self harm etc,.

0 notes

Text

wk2 hw baijia huang

The declaration ‘Information wants be free but is everywhere in chains’, which is the reason for revolutionary change. There are some factors impose unnecessary deprivation, which is the contradictions of contemporary modes of production, distribution and consumption. But most important thing is the information is nonrivalrous. Furthermore, vectorealism means the denial of the brave new. Hackers produce this. So, hacking therefore begins with abstraction, in other words, it will construct previously unrealized relationships and distinctions through thoughts and things. Unfortunately, the hacker gradually become the coodization. Wark offers a glimpse of potential new worlds. In my mind, wark means hack, by mashing up Romantic idealism with historical materialism.

0 notes

Text

How "America First" Undermines Our Health

This article was originally posted on Hastings Bioethics Forum, a blog of the Hastings Center.

People value their health. It allows them to pursue their aims and enjoy their lives, and it contributes to their well-being. But health is not only good for particular healthy individuals. It is also good for their families, communities, nations, and in a world in which people flows are global, health is good for the global community. Health fosters robust economies and fruitful innovation. It has a spillover effect. Because people are socially embedded, it is difficult to exclude others from the good and bad health of individuals. This can be clearly seen with respect to contagious diseases, and with vaccinations and herd immunity. If enough people have been vaccinated, the immunity provided by the vaccination is conferred on people who have not been vaccinated. In the absence of social isolation, the benefits (and harms) of health extend to others. Not only does one person’s health not deprive others of health, it very often contributes to the health of others.

Put differently, our health depends on the health of others. The social determinants of health provide another good example of how health depends upon other people. Inequality, for example, harms the health of rich and poor, though the poor are more vulnerable. Studies also show that social networks are important for health. For example, the likelihood that a person will be obese increases when their social networks include many obese people. A similar phenomenon has been observed with depression. Social determinants of health, such as inequality and our social networks, are critical for health. Indeed, some studies show that the social determinants are more important for health than medical care. Because people are social and thrive in the company of others, it is difficult, if not impossible, to limit their exposure to the health of other people. As it turns out, loneliness and social isolation are also risk factors for health. So even if one could limit one’s exposure to the social underpinnings of health, it would be counterproductive to do so.

Economists call goods with these characteristics public goods. Public goods are nonrivalrous and nonexcludable. Fireworks are a good example. One person’s enjoyment of fireworks does not interfere with the enjoyment by others. Indeed, collective enjoyment might enhance the experience. It would also be difficult, if not impossible, to exclude people from enjoying them.

Because it is difficult to exclude people from enjoying public goods, people may try to enjoy the good without contributing to it—so-called free riders. In our new book, The Health of Newcomers, Wendy Parmet and I suggest that health understood as a public good should guide health care policy for immigrants. Many nations, including the United States, refuse to provide health care to immigrants, both documented and undocumented. When health is understood as a public good, we can see the inherent irrationality of such policies. The health of natives depends upon the health of immigrants, and, in turn, the health of immigrants on the health of natives. It is therefore in everyone’s interest to ensure the health of others—regardless of whether they are native or newcomer.

Understanding the public good dimension of health can also alert us to the moral risk that arises when we refuse to provide newcomers with health insurance. Newcomers tend to be younger and healthier than natives. When natives refuse to protect the health of newcomers, but nonetheless enjoy the health benefits that newcomers bring, natives are free riding, and thereby violating basic principles of justice and fairness.

When it comes to health, it is in our interest to promote the health of all people—distant strangers, natives, and newcomers. In view of health’s public good dimension, an America-first perspective toward health will simply not work.

A wall could be built, and strangers could be kept out, but as long as there are people crossing national borders for business, tourism, and family, the diseases of people in other countries will have an impact worldwide, and so too will our health impact theirs. Similarly, given the public good nature of health, it is very much in the interest of the United States to ensure that newcomers, neighbors, and the global community are as healthy as possible. When the health of others suffers, so too will our health. When the health of others flourishes, so too will ours. Health has the potential to bridge differences and underscore our common humanity.

Patricia Illingworth, J.D., Ph.D., is a research fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, and a professor at Northeastern University. She is the author, with Wendy E. Parmet, of The Health of Newcomers: Immigration, Health Policy, and the Case for Global Solidarity, published in January.

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

from http://ift.tt/2oVzmgv from Blogger http://ift.tt/2p5bjZA

0 notes

Text

How "America First" Undermines Our Health

This article was originally posted on Hastings Bioethics Forum, a blog of the Hastings Center.

People value their health. It allows them to pursue their aims and enjoy their lives, and it contributes to their well-being. But health is not only good for particular healthy individuals. It is also good for their families, communities, nations, and in a world in which people flows are global, health is good for the global community. Health fosters robust economies and fruitful innovation. It has a spillover effect. Because people are socially embedded, it is difficult to exclude others from the good and bad health of individuals. This can be clearly seen with respect to contagious diseases, and with vaccinations and herd immunity. If enough people have been vaccinated, the immunity provided by the vaccination is conferred on people who have not been vaccinated. In the absence of social isolation, the benefits (and harms) of health extend to others. Not only does one person’s health not deprive others of health, it very often contributes to the health of others.

Put differently, our health depends on the health of others. The social determinants of health provide another good example of how health depends upon other people. Inequality, for example, harms the health of rich and poor, though the poor are more vulnerable. Studies also show that social networks are important for health. For example, the likelihood that a person will be obese increases when their social networks include many obese people. A similar phenomenon has been observed with depression. Social determinants of health, such as inequality and our social networks, are critical for health. Indeed, some studies show that the social determinants are more important for health than medical care. Because people are social and thrive in the company of others, it is difficult, if not impossible, to limit their exposure to the health of other people. As it turns out, loneliness and social isolation are also risk factors for health. So even if one could limit one’s exposure to the social underpinnings of health, it would be counterproductive to do so.

Economists call goods with these characteristics public goods. Public goods are nonrivalrous and nonexcludable. Fireworks are a good example. One person’s enjoyment of fireworks does not interfere with the enjoyment by others. Indeed, collective enjoyment might enhance the experience. It would also be difficult, if not impossible, to exclude people from enjoying them.

Because it is difficult to exclude people from enjoying public goods, people may try to enjoy the good without contributing to it—so-called free riders. In our new book, The Health of Newcomers, Wendy Parmet and I suggest that health understood as a public good should guide health care policy for immigrants. Many nations, including the United States, refuse to provide health care to immigrants, both documented and undocumented. When health is understood as a public good, we can see the inherent irrationality of such policies. The health of natives depends upon the health of immigrants, and, in turn, the health of immigrants on the health of natives. It is therefore in everyone’s interest to ensure the health of others—regardless of whether they are native or newcomer.

Understanding the public good dimension of health can also alert us to the moral risk that arises when we refuse to provide newcomers with health insurance. Newcomers tend to be younger and healthier than natives. When natives refuse to protect the health of newcomers, but nonetheless enjoy the health benefits that newcomers bring, natives are free riding, and thereby violating basic principles of justice and fairness.

When it comes to health, it is in our interest to promote the health of all people—distant strangers, natives, and newcomers. In view of health’s public good dimension, an America-first perspective toward health will simply not work.

A wall could be built, and strangers could be kept out, but as long as there are people crossing national borders for business, tourism, and family, the diseases of people in other countries will have an impact worldwide, and so too will our health impact theirs. Similarly, given the public good nature of health, it is very much in the interest of the United States to ensure that newcomers, neighbors, and the global community are as healthy as possible. When the health of others suffers, so too will our health. When the health of others flourishes, so too will ours. Health has the potential to bridge differences and underscore our common humanity.

Patricia Illingworth, J.D., Ph.D., is a research fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, and a professor at Northeastern University. She is the author, with Wendy E. Parmet, of The Health of Newcomers: Immigration, Health Policy, and the Case for Global Solidarity, published in January.

-- This feed and its contents are the property of The Huffington Post, and use is subject to our terms. It may be used for personal consumption, but may not be distributed on a website.

from Healthy Living - The Huffington Post http://huff.to/2o1zkim

0 notes