#moving company in the bronx

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

When it comes to relocating, finding a reliable moving company is crucial for a stress-free experience. Whether you are moving locally or long distance, the logistics can be overwhelming. That's why it's important to choose a professional service like Bronx Moving Company - Flat Fee Moving LLC to ensure everything goes smoothly.

From packing your belongings carefully to transporting them safely, Bronx Moving Company - Flat Fee Moving LLC offers comprehensive moving solutions tailored to your needs. Their team of experienced movers is trained to handle all types of items, ensuring that even the most delicate possessions arrive at your new home intact.

One of the key benefits of using Bronx Moving Company - Flat Fee Moving LLC is their commitment to customer satisfaction. They provide personalized service, working closely with you to plan every detail of your move. This attention to detail helps prevent any issues and ensures a seamless transition to your new location.

Additionally, Bronx Moving Company - Flat Fee Moving LLC offers competitive pricing without compromising on quality. Their transparent pricing structure means there are no hidden fees, giving you peace of mind and allowing you to budget effectively for your move.

For any inquiries or to schedule your move, you can contact Bronx Moving Company - Flat Fee Moving LLC at the following:

Phone: (917) 905-7576

Email: https://bronxflatfeemovers.com/

Address: 2037 Westchester Ave, Bronx, NY 10462, United States1

In summary, when you're planning your next move, consider the reliable services of https://bronxflatfeemovers.com/. With their expertise and dedication to excellence, you can rest assured that your move will be handled with the utmost care and professionalism.

0 notes

Text

Ready to move to the Bronx? Start planning today for a stress-free tomorrow! For more information, visit our website at https://moversnotshakers.com/bronx/ or call us at 718-243-0221.

#bronx movers#professional movers nyc#local moving company nyc#packers and movers nyc#furniture movers nyc

0 notes

Text

youtube

The Padded Wagon : Commercial Moving Solutions In New Jersey

The Padded Wagon is a reliable and experienced commercial moving company that offers tailored moving solutions to businesses in New Jersey. Our team of professional movers has the expertise and resources to handle all types of commercial moves, from small offices to large corporate relocations. We strive to provide a seamless and efficient moving experience that minimises downtime and disruption to your operations. https://goo.gl/maps/q4UjqVcQnCD11PMQ6

https://www.facebook.com/thepaddedwagon

https://www.instagram.com/thepaddedwagon/

1 note

·

View note

Text

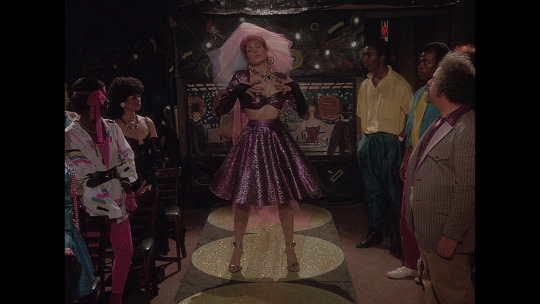

Miami Vice S1E18: Made for Each Other

Larry's house burns down, and Izzy and Noogie are sent undercover.

Made for Each Other suffers immensely from coming right after The Maze, which is a true "the system is broken" classic Vice episode. Made for Each Other is a comedy breather, and actually kind of great in its own right, but where it sits in the progression of the series feels more like a deflation than a break.

Made for Each Other is also almost comically homoerotic-- it's the episode that convinced me that Sonny is supposed to be a textually closeted bisexual man on my first watch through of the series, but on a repeat watch it's somehow even more obvious. Why are there all those half-naked bears on a boat? Why is the entire plot basically "Stan and Larry sort of have a breakup because of Stan's new girlfriend and then get back together at the end?" Why does Izzy keep saying things like nubile and anal? Why does the camera linger so very long on his and Noogie's cigarillos touching? What's up with the repetition of 'shafted'? Why are all the guests at Noogie's wedding like, extras from a Boy George video?

Why does this happen?

(plz draw your OT3 like this)

Anyway I actually really like Made For Each Other upon rewatch, it really just should have been placed elsewhere in the season. It's a fun, silly episode, and a little levity is necessary in a series that is often so very bleak.

The episode opens with Sonny and Rico trying to catch a counterfeiter, and Rico is bitchy and condescending to Sonny in a way that I think is supposed to be "ha ha, my criminal persona is a dick," but actually just comes off as "ha ha, I am a dick." It seems like he's trying to impress the counterfeiter by throwing Sonny under the bus. This occasional cruelty towards someone he does genuinely like is a fascinating part of Rico's characterization, and part of what elevates his character writing to "actual nuanced person" and not "nice Black sidekick who always supports the main white guy." Rico absolutely sees himself as more educated and worldly than Sonny, and occasionally he lets that slip. He has a very complicated relationship to both class and geography-- he's a New Yorker (...from the Bronx), he wears a perfectly tailored suit everyday (...and is a poorly paid cop), he idolizes Sonny for his football career but also thinks he's a bit of a yokel. As someone whose own class status is a bit shaky, Rico tends to get a little mean when it seems like he might be 'found out.'

Zito almost gets blown up in the ensuing warehouse fire, and Switek flips out. A short while later, a surprisingly chill Zito says he believes things are "either in whack or out of whack," shortly after while they discover that his entire house is on fire.

Please note the company that moves Zito's stuff to Switek's house:

I am dying

Trudy and Gina, in their only real appearance in the episode, very sweetly present Zito with a new fish as an office gift. Sonny is a dick about it.

Swi and Zito go to investigate BONZO BARRY who is a shady stereo and computer system dealer who has a FUCKING SEAL in his store

Michael Talbott is wildly overacting this entire episode, like to the point that I wonder if they had to turn down his mic

Noogie is marrying a stripper(?) named Ample Annie. They argue about going to Disneyland while she's practicing her routine. She does a striptease down the aisle. She is perhaps the only person bonkers enough to keep up with Noogie.

Stan's girlfriend, Darlene (who was Larry's girlfriend a short period of time ago), is extremely unhappy with Larry staying at their house, and spends the entire episode either complaining or being upset that the conditions are not right to bone; frankly, Stan does not seem to like her and she does not seem to like Stan. The most likely reasoning behind this is "bad 80's hurr hurr the ol' ball and chain" comedy, but considering the homoeroticism of the episode I'd like to think it could be a comment on compulsory heterosexuality

Izzy and Noogie show up at Stan's and, in one ridiculous whirlwind, declare the current case "theirs," ask who is the "Captain Kirk of this Enterprise," and start eating Stan's breakfast

In one scene Tubbs asks Zito and Swi if they want backup and they both very loudly yell NO like he's the reason everything has been on fire in this episode

Switek asks Zito at one point, "do you ever think about the future, Larry?" and Zito answers No.

This is funny the first time you watch the episode!

This is not funny anymore after Season 3.

The bad guy (whose crime seems to be like. Selling stolen stereos or something equally stupid) has a boat full of half-naked men with guns. This is not remarked upon.

Then we get to the Night Talk scene. I've talked at length about this scene before, but basically: Zito has been kicked out of Switek's and is sleeping at the station; Sonny comes in, romantic music plays, Zito basically describes Switek as the perfect man, and Sonny tries to get Zito to come back to his place (and fails.) It's very gay. I like to think that Sonny has a burgeoning crush on Rico at this point but is certain Rico is straight (and also. Y'know. Was a bit of an asshole at the beginning of the episode.) and takes desperate, tragic shot on Zito because of that. Zito politely declines because his heart is already spoken for.

Meanwhile, Stan is unable to perform sexually because he's thinking about Larry.

I'm sure that means nothing.

The outfits at Noogie's wedding are just. They are. Truly they are something.

The priest is a leather daddy. Many people appear to be in space blankets, including Noogie. Annie has a tearaway wedding dress. The pianist has the world's most incredible zebra shirt. There are headbands and weird hats abound.

By contrast, all the members of Vice look like they're supposed to be at a PTA meeting. (Also Sonny looks like he wishes he could ask where the punch is but doesn't want to bother Gina and Trudy, who are clearly each others' plus-ones.)

And the episode ends with Switek and Zito, side by side, at a wedding.

#miami vice#miami vice s1#s1e19#made for each other#larry zito#stan switek#izzy moreno#noogie lamont#sonny crockett#my gifs

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Little Mac hcs but instead of general hcs he realizes his true potential and becomes a public menace like every other high schooler (the Bronx fears him)

hell yeah broski 😈😈😈

evil below cut 😈😈😈

- after realizing his potential his amazing potential for evil, he teams up with aran and starts to terrorize the Bronx

- He first starts with fake stickers of pennies, dollars, wall sockets etc just to watch people struggle

- He then starts to make fake posters about missing stuff, including masterpieces like : "have you seen my pancreas?", "my evil twin big whopper has been set free!" And other dumb shit like that

- at first people found it funny, what not people found funny was him torturing the minor circuit with dumb wanted posters, imagine something with glass joe's face on it with text that says "WARNING! THIS MAN WILL SNIFF OUT YOUR CREDİT CARD INFO WITH HIS HUMOUNGUS NOSE!!" And making posters accusing king hippo of eating a boulder

- He then moved onto the major circuit, taking pictures of don flamenco without his wig and playing a game of tic tac toe on it with a stranger before releasing it onto the wild like a rabid animal

- He teamed up with von kaiser's students and bullied him for getting beaten up by children on 3 different occassions, making dumb "no little german boy!!" posts about him

- where he truly caused chaos was the world circuit, he pretended to be Sandman sending a note to bull and bull sending a note to Sandman telling him to fight him, then he sent a note to soda popinski telling him that Sandman and bull are planning to go against him in a oil wrestling match and sent a note to super macho man that his next photoshoot is gonna be in the locker by pretending to be whatever company he talks to, the only person he told the truth was aran and he came to watch it unfold

- doc started to get pissed off by macs antics and proceeded to scold him, it didnt work and he trapped glass joe in a locker the next day

- He sent mail to mrs bear telling her that don flamenco wanted to fight to the death with her, mrs bear directed it to bear hugger and he directed it to don flamenco, he of course denied it and started to catch wind of what was going on

- it all ended with the boxes taping Mac to the ceiling and laughing at him

#punch out#headcanon#punch out wii#punch out headcanons#aran ryan#don flamenco#bald bull#glass joe#piston hondo#little mac#doc louis#this was so fun to do for what#hes just evil

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evelyn Berezin in 1976 at the Long Island office of her company Redactron. She developed one of the earliest word processors and helped usher in a technological revolution. Evelyn Berezin said her word processor would help secretaries become more efficient at their jobs. Photo By Barton Silverman/New York Times.

Evelyn Berezin, “Godmother of the Word Processor!” The Woman That Made Bill Gates and Steve Jobs Possible

Evelyn Berezin (1925-2018) was born in the Bronx to poor Russian-Jewish immigrants. Growing up, she loved reading science fiction and wished to study physics. She excelled at school and graduated two years early. Berezin had to wear make-up and fake her age to get a job at a research lab. She ended up studying economics because it was a more “fitting” subject for women at the time. During World War II, she finally received a scholarship to study physics at New York University. Berezin studied at night, while working full time at the International Printing Company during the day. She continued doing graduate work at New York University, with a fellowship from the US Atomic Energy Commission. In 1951, she joined the Electronic Computer Corporation, designing some of the world’s very first computers. At the time, computers were massive machines that could only do several specific functions.

Evelyn Berezin, “Godmother of the Word Processor.” Born: April 12, 1925, The Bronx, New York City, NY — Died: December 8, 2018, ArchCare at Mary Manning Walsh Nursing Home & Rehabilitation Center, New York, NY

Berezin headed the Logic Design Department, and came up with a computer to manage the distribution of magazines, and to calculate firing distances for US Army artillery. In 1957, Berezin transferred to work at Teleregister, where she designed the first banking computer and the first computerized airline reservation system (linking computers in 60 cities, and never failing once in the 11 years that it ran). Her most famous feat was in 1968 when she created the world’s first personal word processor to ease the plight of secretaries (then making up 6% of the workforce).

“Without Ms. Berezin There Would Be No Bill Gates, No Steve Jobs, No Internet, No Word Processors, No Spreadsheets; Nothing That Remotely Connects Business With The 21st Century.” — The Times of Israel (12 December 2018)

The following year, she founded her own company, Redactron Corporation, and built a mini-fridge-sized word processor, the “Data Secretary”, with a keyboard and printer, cassette tapes for memory storage, and no screen. With the ability to go back and edit text, cut and paste, and print multiple copies at once, Berezin’s computer freed the world “from the shackles of the typewriter”. The machine was an in instant hit, selling thousands of units around the world. Berezin’s word processor not only set the stage for future word processing software, like Microsoft Word, but for compact personal computers in general. It is credited with being the world’s first office computer. Not surprisingly, it has been said that without Evelyn Berezin “there would have been no Bill Gates, and no Steve Jobs”.

Evelyn Berezin Pioneered Word Processors and Butted Heads With Men! A ‘loud woman,’ she studied physics and found that to get to the top she had to start her own company. Evelyn Berezin later became a mentor to entrepreneurs, venture capitalist and director of companies. Photo: Berezin Family. Wall Street Journal

“Why Is This Woman Not Famous?” British Writer Gwyn Headley Wrote In A 2010 Blog Post. — The Times of Israel

Redactron grew to a public company with over 500 employees. As president, she was the only woman heading a corporation in the US at the time, and was described as the “Most Senior Businesswoman in the United States”. Redactron was eventually bought out by Burroughs Corporation, where Berezin worked for several more years. In 1980, she moved on to head a venture capital group investing in new technologies. Berezin served on the boards of a number of organizations, including Stony Brook University and the Brookhaven National Laboratory, and was a sought-after consultant for the world’s biggest tech companies.

She was a key part of the American Women’s Economic Development Corporation for 25 years, training thousands of women in how to start businesses of their own, with a success rate of over 60%. In honour of her parents, she established the Sam and Rose Berezin Endowed Scholarship, paying tuition in full for an undergraduate science student each year. Sadly, Berezin passed away earlier this month. She left her estate to fund a new professorship or research centre at Stony Brook University. Berezin won multiple awards and honourary degrees, and was inducted into the Women in Technology International Hall of Fame.

#Evelyn Berezin#Business & Finance#Science & Technology#Steve Jobs#Bill Gates#Computers#Computer Science#Microsoft Word#New York University#Physics#Teleregister#Word Processor#WWII#Redactron#Belarusian 🇧🇾 Russian 🇷🇺 Jewish

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A fake encampment was created at Queens College by CBS for the show FBI: Most Wanted on Monday (22 Jul). For clarification, the first two photos (with the fake tents and fake broken windows) are staged; the last two photos (with the person in the paramedic jacket and the placards) are of the real counterprotest.

Pro-Palestine advocates are criticizing Queens College, a school of the City University of New York (CUNY), for hosting a two-day TV production involving a prop protest encampment following an administrative crackdown on students for their Gaza advocacy efforts earlier this year. The imitation campsite, consisting of multicolored tents and signs featuring ambiguous environmental protest language and deliberately misspelled words, is part of an ongoing shoot for CBS’s FBI: Most Wanted, a television series by Wolf Entertainment. According to an email sent by Queens College to community members, shared on X by Within Our Lifetime (WOL) organizer Nerdeen Kiswani, the mock encampment would feature “signage and branding for a fictitious university”; a “chase and arrest scene”; and a staged set with tents, firecrackers, and smoke effects. In response to Hyperallergic’s request for comment, a Queens College representative stated that the school “is often the site of television and film shoots by reputable production companies and media outlets.”

“The campus community was advised in advance of the anticipated media shoot parameters, including the fact that the episode would focus on a climate change/environmental issue protest at a fictitious college,” the spokesperson said, adding that filming was completed today before noon.

Yesterday, July 22, the shoot was the focus of at least two actions led by pro-Palestine groups WOL, CUNY for Palestine, and National Students for Justice in Palestine. At Queens College, protesters alleged that their demonstration forced filming to wrap early, and outside the CUNY Graduate Center in Midtown Manhattan, more than 150 pro-Palestine advocates gathered to protest, joined by around 30 pro-Israel counterprotesters.

“We’re here to send a very clear message to the CUNY administration that we will not stop until they drop the charges and until they meet the demands of student organizers,” Kiswani and other protesters at the Manhattan rally said in a call-and-response chant. “But instead, what does CUNY do? They rent out Queens College for a film shoot for FBI: Most Wanted, where they set up a fake encampment to capitalize [on] the momentum of the Palestinian struggle,” the protesters continued, echoing long-standing calls for the school to divest from Israeli military interests and sever its relations with all Israeli academic institutions.

Carol Lang, an assistant professor at Bronx Community College who was at yesterday’s protest at the Graduate Center, told Hyperallergic that she broke a rib when police raided the City College of New York’s student solidarity encampment at the end of April, arresting 173 people. “[The police] knocked me down, and kept saying, ‘Move! Move!’ but there was no place to move. It was just this really big crowd, so we all fell on top of each other and my knee got all messed up when I slammed it against the ground,” Lang said. Hyperallergic has reached out to the New York Police Department about the allegations. “The criminalization of students who participated in encampments to stop a genocide is comical,” a protester at the Graduate Center who asked to remain anonymous told Hyperallergic. They added that they were suspended from their out-of-state school for participating in a solidarity encampment, which was also targeted by “many arrests and many suspensions.”

-- "TV Show’s Bizarre Mock Student Encampment Draws Protests in NYC" by Maya Pontone for Hyperallergic, 23 Jul 2024

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The North Star - Part Five: Ask Me Again (NSFW) - Terry Bruno x Reader

Welcome to mine and @the-hinky-panda The Bronx universe featuring our favs Terry Bruno & Mike Duarte.

This story takes place several years after 'Blood Out'. Terry still lives in the Bronx and works in Manhatten SVU.

Following on from @the-hinky-panda story 'The Dog' Mike has retired from the NYPD on medical grounds due to seizures causes by the attack. He has a therapy dog called Bono and lives with @the-hinky-panda character Meredith.

Tagging: @mysoulisasunflower @legit9thlunaticwarrior @bbyxoo @the-adzukibean @xoxabs88xox @crazy4chickennuggets @beardedbarba @wooshwastaken @justreblogginfics @im-just-a-mississippi-girl @storiesofsvu @anime-weeb-4-life

Part One: Moments

You fall asleep on the car ride home, Terry’s jacket draped over you, pulled up to your chin. The temperature had dropped by the time you left Meredith’s. He runs hot, he always has but he knows you feel the cold. This thing with Paul, and this case it’s exhausting you. You’ve stayed late the last couple of nights, and he sees the weight pressing down on your shoulders. The robberies are high profile, increasingly violent and now they’ve taken an even darker turn which is how they’ve landed at your feet. The victims are mostly from City Park and the Spencer Estates, the latest now being Morris Park. The homeowners are not Upper East Side rich, but the items that were stolen were heirlooms, past down from generation to generation. Duarte thinks there’s something in that, all these pieces are one of a kind, historical items, each of their stories running so deep you can feel the echo of generations when you look at the pictures.

He turns down Billy Joel on the radio as he pulls up in front of his apartment building. His head tilts towards you and he smiles. You’re curled up in the heated seat, head resting against the window. There’s a contented smile on your features and he loves that, loves the fact you feel comfortable enough with him to let your guard down.

A little wine, some good food, and excellent company can solve all the world’s woes.

“Hey pretty girl,” he says softly into the darkness of the car as he uses gentle fingertips to brush a strand of hair away from your features. “We’re home.”

“Hm…” You grumble, shuffling further down into the confines of his jacket. “Leave me, I’m comfortable here.”

Terry chuckled, his thumb tracing over the apple of your cheek. You leaned into his touch, your lips brushing over the base of his palm.

“I’m not letting you sleep in the car.” He says with a smile as he undoes your seatbelt.

“Always such a hardass.” You mumble, rubbing the back of your wrist across your tired eyes.

“Somebody has to take care of you.”

“You always do.” You told him resolutely. “I trust you more than I trust myself sometimes.”

“Nah, you’ve got good instincts.” Terry said. His fingertips caught the delicate gold chain around your throat, following the trail down to the centre of your chest where that tiny compass resided. “You just need to listen to them.”

“I do.” You told him, your gaze lowering to the compass between his fingertips. “When I’m not sure where I’m headed, I look down at this and think what would Terry do? And then I do the opposite.”

Terry rolled his eyes before releasing the compass.

“My girl, the comedian.”

There was silence for a second as Terry unclasped his own seatbelt and removed the keys from the steering console.

“I do want to move in with you, you know?” You said abruptly, the words spilling from your lips. “It’s just hard for me.”

“I know.” He said, his lips pursing together grimly, his fingers wrapping around the steering wheel. “Meredith told me.”

“I didn’t want you to see me as a victim, the work you do…” You trailed off, swallowing hard against the well of emotion in your chest. “I didn’t want you to have that in your home life too.”

“I don’t see you as a victim.” Terry said inclining his head towards you. “I see you as a survivor. You went through something awful at the hands of someone who was supposed to care about you and you’re still standing. Do you know how much strength it takes to do that?” Terry asked, angling his body towards you. “To get yourself out of that situation. You must have been terrified and you pushed through it. I admire that, I respect that.”

“Look…” Terry said meeting your gaze. His hand reached out to clasp yours, his thumb trailing over the indentation of your knuckles. “Move in with me, don’t move in with me. It doesn’t matter. I just want you feel safe, I want you to be able to sleep at night and know that everything’s going to be ok, that nothing is going to hurt you.”

“I love you; you know that?” You told him, leaning in close and inhaling that intoxicating scent. Your fingertips traced over the line of his jaw, your lips brushing over his softly. “Sometimes I look at you and I wonder how I got so lucky.”

“Luck had nothing to do with it.” Terry said quietly as he kissed you. “The two of us, it’s fate.”

----------------------------------------------------------------------

“Ask me again.” You whisper against his lips. You have him at your mercy, your hands threaded in his hair as you straddle his lap, his cock buried deep inside of you. There’s a flush across both of his cheeks, it reminds you of peaches and cream as you arch just a little taking him even deeper. His eyes are wild, locked on yours as you rock just a little coaxing a low moan from his throat. You have him at his peak, standing at the crest of the mountain and you are right there with him. His calloused palms roam up your curve of your back, clasping you close, holding on for dear life.

“Move in with me.”

His voice is husky and rough, his pupils blown as you sink down on him once more, tugging his head back and baring his throat. There’s an intimacy in the gesture, a sense of vulnerability and trust. You love him and this is your way of showing it, of reminding him that he’s yours, he’ll aways be yours.

You tantalise, you tease, you strip away every ounce of his control until he’s desperate and reckless, skin pressed so tightly against yours because he can’t stand not to touch you, not to feel you on every level. You drive him to the precipice, holding him there until the only thing he can focus on is the blurring of heaven and earth as he hits that rapture.

“Please, pretty girl.” He asks as he clings to the edge.

You know what he’s asking, it’s not just the moving in, it’s the commitment. The promise that you’re ready to take the next step, that you’re ready to trust him as much as he trusts you. It’s the final act, the shedding of that fear that sends you hurtling over the edge and plummeting into the sea of ecstasy. It washes over your synapses, drowning you like a wave until the only word on your lips is ‘yes’. You lose track of yourself, but Terry is always there, always grounding you. His hands are on your hips, his mouth smothering yours, drinking down your moans, your words and everything else you can give him as he spills himself inside of you.

You lose yourself in the bliss, the sense of belonging that comes with this man as he kisses you like you’re the only woman in the world. The only one he’s ever truly loved.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

It rains that night. Terry can hear the patter on the bedroom window as he lies in the darkness with your body draped over his. Your face is buried in the hallow of his throat, your arm thrown over his chest. His thumb trails over the curve of your spine, caressing your bare skin underneath the sheets. There was a perfection in this moment. The rhythm of your breathing against his. In the space of twenty-four hours his life has been flipped upside down and now he was considering the future.

There was a house for sale in Meredith’s neighbourhood, a couple of bedrooms, a small yard if you wanted a dog. It needed a little work, but the location was solid, and he had the money to renovate. He knew you would fight him on that point but the two of you would work out the details, you always did.

He thinks of the house with hardwood floors, your Aztec style rug in the living room along with his couch. A king-sized bed to go with the quilt he’d had to buy in the beginning of the relationship because you hoovered up the duvet when you were cold. The matching nightstands, you’d bought from a thrift shop before upcycling them with wallpaper and chalk paint. He wants to build a home with you, a place filled with laughter and love. He wants it to belong to both of you, for you to be able to come home and just relax in a space of your own. He longs for nights where you fall asleep with your head in his lap, a fire burning in the hearth, his fingers stroking through your hair. The two of you content.

This is what he falls asleep thinking about, with you in his arms. The life the two of you will have, the one you’ll create together.

Love Terry Bruno? Don’t miss any of his stories by joining the taglist here.

Like My Work? - Why Not Buy Me A Coffee

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

What to say about Rock in Rio 2024.

I expected to see something different. I was there to have fun, you know, and I felt angry that I didn't have enough fun. And man, I live in Brazil and I listen to Brazilian music every day.

The Rock in Rio 2024 music scene was driven by the big record companies. Artists who were very successful in the 1990s invaded Rock in Rio. I saw country music duos, who performed so-called 'country' music, but often far from the roots of Brazilian music. What they played was pure American country.

If I want to listen to country, I'll look for American country artists like Miley Cyrus or Taylor Swift, for example.

Then there were pagode groups, who hit the charts with romantic and standardized sambas. Rock in Rio, however, also gave space to creative artists.

They should show and invite more young people from Rio to sing. They are very talented and surprised me. They are really cool.

I was happy because in the Northeast, a singer complained: “I don’t understand why there aren’t any female rock artists on the main stage. But we are adapting and occupying the spaces we have, what can we do?”

I also liked the artists from the outskirts of the big urban centers. They created a model for musical genres that emerged in the ghettos of Rio. To me, they are black “North Americans,” and they mixed classical music and funk. They don’t participate in record label schemes and even refuse to give interviews to the press. So it’s hard to get to know their work, but it’s very successful.

They are closer to the classical style of MPB. I don’t want to write anything. But Xuxa surprised me. And a percussionist who was booed years ago at Rock in Rio rocked things up.

In electronic music, it was terrible, awful! No real dance music artist showed up. They should have invited Inna. European DJs are really cool and encourage young people to start independent productions. Only some American rap artists saved the dance genre and Katy Perry mixed her music with electronic music. It was like a typical breakdance street dance that emerged in the Bronx neighborhood of New York as a form of expression used by rival youth groups and became popular. I saw a movie called Flashdance by Adrian Lyne and listened to

Salt - n - Pepa…

youtube

The Americans showed acrobatic moves like Katy Perry, such as spinning on her back or head, keeping her limbs stationary, combining elements of dance with the most shocking and provocative moves of rap musicians.

In rock, I didn't see anything new… the singer of Evanesse was voiceless.

On the international and national scene, "as a whole", a bunch of old male and female singers appeared that no one listens to anymore. Next year, repeat the feat.

But Rock in Rio featured 50% Brazilian artists and the normal number should be 92% American musicians from abroad.

https://www.tumblr.com/nadiegesabate1990/762178133469413376/will-rocked-it-with-a-23-minute-show-and-ed-had-to?source=share

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering a childhood in the South Bronx.

As an aspiring actor, Pacino, seen here in 1972, would practice Shakespeare monologues while wandering the city streets.Photograph by Jerry Schatzberg / Trunk Archive

By Al Pacino August 26, 2024

My mother began taking me to the movies when I was a little boy of three or four. She worked at factory and other menial jobs during the day, and when she came home I was the only company she had. Afterward, I’d go through the characters in my head and bring them to life, one by one, in our apartment.

The movies were a place where my single mother could hide in the dark and not have to share her Sonny Boy with anyone else. That was her nickname for me. She had picked it up from the popular song by Al Jolson, which she often sang to me.

When I was born, in 1940, my father, Salvatore Pacino, was all of eighteen, and my mother, Rose Gerardi Pacino, was just a few years older. Suffice it to say that they were young parents, even for the time. I probably hadn’t even turned two when they split up. My mother and I lived in a series of furnished rooms in Harlem and then moved into her parents’ apartment, in the South Bronx. We hardly got any financial support from my father. Eventually, we were allotted five dollars a month by a court, just enough to cover our expenses at my grandparents’ place.

The earliest memory I have of being with both my parents is of watching a movie with my mother in the balcony of the Dover Theatre when I was around four. It was some sort of melodrama for adults, and my mother was transfixed. My attention wandered, and I looked down from the balcony. I saw a man walking around below, looking for something. He was wearing the dress uniform of an M.P.—my father served as a military-police soldier during the Second World War. He must have seemed familiar, because I instinctively shouted out, “Dada!” My mother shushed me. I shouted for him again: “Dada!” She kept whispering, “Shh—quiet!” She didn’t want him to find her.

He did, though. When the film was over, I remember the three of us walking down a dark street, the Dover marquee receding behind us. Each parent held one of my hands. Out of my right eye, I saw a holster on my father’s waist, a huge gun with a pearl-white handle sticking out of it. Years later, I played a cop in the film “Heat,” and my character carried a gun with a handle like that. Even as a child, I understood: That’s dangerous. And then my father was gone, off to the war. He eventually came back, but not to us.

My mother’s parents lived in a six‐story tenement on Bryant Avenue, in a three-room apartment on the top floor, where the rents were cheapest. Sometimes we would have as many as six or seven people living there at once. I slept between my grandparents or in a daybed in the living room, where I never knew who might end up camped out next to me—a relative passing through town, maybe my mother’s brother, back from his own stint in the war. He had been in the Pacific and would take wooden matchsticks and put them in his ears to drown out the explosions he couldn’t stop hearing.

My mother’s father was born Vincenzo Giovanni Gerardi, and he came from an old Sicilian town whose name, I would later learn, was Corleone. When he was four years old, he came to America, possibly illegally, where he became James Gerardi. By then, he had already lost his mother; his father, who was a bit of a dictator, had remarried and moved with his children and new wife to Harlem. My grandfather didn’t get along with his stepmother, so at nine he quit school and ran away to work on a coal truck. He didn’t come back until he was fifteen. He wandered around upper Manhattan and the Bronx—this was in the early nineteen-hundreds, when it was still largely farmland—doing apprentice jobs or working in the fields. He was the first real father figure I had.

When I was six, I came home from my first day of school and found him shaving in our bathroom. He was in front of the mirror, in a BVD shirt with his suspenders down at his sides. I was standing in the open doorway.

“Granddad, this kid in school did a very bad thing. So I went and told the teacher, and she punished that kid.”

Without missing a stroke, my grandfather said, “So you’re a rat, huh?” It was a casual observation, as if he were saying, “You like the piano? I didn’t know that.” His words hit me right in the solar plexus. I never ratted on anybody in my life again. (Although right now, as I write this, I guess I’m ratting on myself.)

His wife—my grandmother Kate—had blond hair and blue eyes, like Mae West, which was a rarity among Italians. We were the only Italians in our neighborhood, and she was known for her kitchen. When I’d be going out the door, she would stop me with a wet cloth, which always seemed to be in one of her hands, to say, “Wipe the gravy off your face. People will think you’re Italian.” America had just spent four years fighting Italy, and though many Italian Americans had gone overseas to help, others were labelled enemy aliens and put in internment camps. There was still a stigma against us.

Our little stretch between Longfellow Avenue and Bryant Avenue, from 171st Street up to 174th Street, was a mixture of nationalities and ethnicities. In the summertime, when we went on the roof of our tenement to cool off because there was no air-conditioning, you’d hear all kinds of languages and dialects. The farther north you went, the more prosperous the families were. We were not prosperous. We were getting by. My grandfather was a plasterer who worked during the week. Plasterers were highly sought after at the time. He had developed an expertise and was appreciated for what he did. He built the wall that separated our alleyway from the alleyway of the building next door for our landlord, who loved it so much that he kept our family’s rent at thirty-eight dollars and eighty cents a month for as long as we lived there.

I was an only child, and until I was six I wasn’t allowed out of the tenement by myself—the neighborhood was somewhat unsafe. My only companions, aside from my grandparents, my mother, and a little dog named Trixie, were the characters I brought to life from the movies. I had a little silent routine I did for my relatives from “The Lost Weekend”—starring Ray Milland as a self‐destructive alcoholic—in which I pretended to ransack an apartment, looking for booze. The grownups seemed to find it amusing. Even at five years old, I would think, What are they laughing at? This man is fighting for his life.

My mother was a beautiful woman, but she was emotionally fragile. She would occasionally visit a psychiatrist when Granddad had the money to pay for her sessions. I wasn’t aware that my mother was having problems until one day when I was six years old and getting ready to go out and play. I was sitting in a chair in the kitchen while my mother laced up my shoes and put a sweater on me to keep me warm, and I noticed that she was crying. I wondered what the matter was, but I didn’t know how to ask. She was kissing me all over, and right before I left she gave me a great big hug. It was unusual, but I was eager to get downstairs and meet up with the other kids, and I gave it no more thought.

We had been outside for about an hour when we saw a commotion in the street. People were running toward my grandparents’ tenement. Someone said to me, “I think it’s your mother.” I didn’t believe it, but I started running with them. There was an ambulance in front of the building, and there, coming out the front doors, carried on a stretcher, was my mother. She had attempted suicide.

This was not explained to me; I had to piece together what had happened. I knew that she had left a note and that she was sent to recover at Bellevue Hospital. That period is kind of a blank to me, but I do remember sitting around the kitchen table, where the grownups were discussing what to do. Years later, I made the film “Dog Day Afternoon,” and one of its final images, showing the actor John Cazale’s character, already dead, being taken away on a stretcher, made me think of the moment I saw my mother brought out to that ambulance. But I don’t think she wanted to die then, not yet. She came back to our household alive, and I went out into the streets.

As a kid, I ran with a crew that included my three best friends: Cliffy, Bruce, and Petey. We were on the prowl, hungry for life. To this day, one of my favorite memories is coming down the stairs and out onto the street in front of my tenement building on a bright Saturday morning in the spring. I couldn’t have been more than ten years old. I remember looking down the block, and there was Bruce, about fifty yards away. He turned and smiled, and I smiled, too, because we knew the day was full of potential.

Every few blocks were vacant lots where victory gardens had been planted at the height of the war. By then, they were wrecked and full of debris. Once in a while, when you looked down at the sidewalk along the lots, you’d see a blade of grass growing up out of the concrete. That’s what my friend, the acting teacher Lee Strasberg, once called talent: a blade of grass growing up out of a block of concrete.

One winter day, I was skating on the ice over the Bronx River. We didn’t have ice skates, so I was wearing a pair of sneakers, doing pirouettes, showing off for my friend Jesus Diaz, who was standing at the shore. One moment I was laughing and he was cheering me on, then suddenly I broke through the surface and plunged into the freezing water below. Every time I tried to crawl out, the ice broke further and I kept falling back in. I think I would have drowned if it wasn’t for Jesus Diaz. He found a stick twice his size, spread himself out as far as he could from the shore, and pulled me to safety.

Another day, I was walking on top of a thin, iron fence, doing my tightrope dance. It had been raining all morning, and, sure enough, I slipped and fell, and the iron bar hit me directly between my legs. I was in such pain that I could hardly walk. An older guy saw me groaning in the street, picked me up, and carried me to my aunt Marie’s apartment. She was my mother’s younger sister, and she lived on the third floor in the same building as my grandparents. The Samaritan threw me on a bed and said, “Take care, man.”

It was customary for doctors to go to people’s houses in those days. While my family waited for Dr. Tanenbaum to come, I lay there on the bed, with my pants down around my ankles as the three women in my life—my mother, my aunt, and my grandmother—poked and prodded at my penis in a semi-panic. I thought, God, please take me now.

Our South Bronx neighborhood was full of characters. There was a guy in his late thirties or early forties who wore a suit and a collared shirt with a loose, tattered tie. He looked like he had gone to a Sunday service and got ashes spilled all over him. He would quietly walk the streets by himself; when he spoke, the only thing he said was “You don’t kill time—time kills you.” That was it. Our instincts told us he was different than we were, but we just accepted him. There was more privacy back then, a certain propriety and distance that people gave one another.

When Cliffy, Bruce, Petey, and I got a little older, eleven or twelve, we spent hours lying flat on our stomachs as we fished through sewer gratings for lost coins. This was not an idle pursuit—fifty cents was a game changer. On Saturday nights, we would see guys just a few years older than us who had started to date, taking girls out to the movies or on the subway, and we’d get up on the storefront roofs and pelt them with trash. Sometimes we’d split up a head of lettuce and toss it at them. A string bean thrown from twenty feet away could really sting.

In the summer, we opened up the hydrants, which made us heroes to all the young mothers who let their small children play in the water. We hitched ourselves to the backs of buses, jumped over turnstiles in the subway. If we wanted food, we’d steal it. We never paid for anything.

We played the old street games, like kick the can, stickball, and ring-a-levio, which involved splitting up into two teams. If you could stick one foot in the circle that was the other team’s jail and shout “Free all!,” your whole gang would get sprung. Kids were known to jump off buildings just to get a foot in that circle.

We were always either chasing someone or being chased. When we’d see cops, we’d yell out, “Hey, what’s a penny made out of?” And then we’d all answer, “Dirty copper!” The cops would yawn or laugh or take off after us, depending on their mood. But we all knew the neighborhood cop on our beat; he kept an eye on us. I don’t know how much violence he stopped, but we grew to love him, and he got a kick out of us. I always thought the guy had a crush on my mother. He’d ask me questions about her, and even at age eleven I sort of knew why.

There were a few others in our little gang—Jesus Diaz, Bibby, Johnny Rivera, Smoky, Salty, and Kenny Lipper, who would go on to become the deputy mayor of New York City under Ed Koch. (I later did a film called “City Hall,” directed by Harold Becker, which was based on his experience.) But Cliffy, Bruce, Petey, and me were the top bananas. They called me Sonny, and Pacchi, their nickname for “Pacino.” They also called me Pistachio, because I liked pistachio ice cream. If we had to choose someone as our leader, it would be Cliffy or Petey. Petey was a tough Irish kid. Cliffy was a true original. Even at thirteen, he was never without a copy of Dostoyevsky in his back pocket. He had talent. He had looks. And he had four older brothers who beat the shit out of him every day. He was full of trickery. You never had to ask him, “What are we going to do today?” He always had a scheme.

Often, when I looked down from my apartment window, I would see my friends—a pack of wild, pubescent wolves with sly smiles—looking up at me from the alley, calling out, “Come on down, Sonny Boy! We got something for ya!” One morning, Cliffy showed up with a huge German shepherd. He yelled up, “Hey, Sonny, wanna look at my dog? He’s my new friend, and his name is Hans!” He had got it from somewhere. Cliffy wasn’t known for taking dogs. Cars were more his thing. Once, he stole a garbage truck. He also used to burglarize houses—at a certain point, he could no longer go to New Jersey because he was wanted by the police there. He would tease me because I never did any of the drugs that he was into. He’d say, “Sonny doesn’t need drugs—he’s high on himself!”

There was one thing that divided me from the rest of the gang. My grandfather had instilled a love of sports in me: he was a lifelong baseball and boxing fan. He grew up rooting for the New York Yankees before they were even the Yankees—as a poor kid, he would watch their games through holes in the fence at Hilltop Park. Later, the Yankees got their own stadium, known as the House That Ruth Built, after Babe Ruth. That stadium is in the background of a scene in “Serpico”—shot by Sidney Lumet with such beauty—in which my character, Serpico, meets with a crew of corrupt cops. It was filmed the same day the actress Tuesday Weld and I broke up, and, if you notice the look on my face, you can tell I was pretty sad.

My grandfather would sometimes take me to baseball games, and we’d sit way up in the grandstand—the cheap seats. I didn’t think of myself as being disadvantaged—the more expensive box seats were just another block in the neighborhood, another tribe. The difference between Cliffy and me was that Cliffy would see those same box seats and want to go down there. If there was a line to get into a movie, he’d cut in front of someone and just go right in. It was like nobody existed but him.

I played baseball for the Police Athletic League team in my neighborhood. Sports were of no interest to Cliffy and the other guys, so it was almost like I lived two lives: my life with the gang, and my life with my pal teammates. One day, as I was coming back from a game in a bad neighborhood, a group of four or five guys not much older than I was got the jump on me; they had knives and God knows what else, and they said, “Give us the glove.” They knew I had no money, and I knew I was losing my glove, which my grandfather had bought for me. I went home in tears. If only I’d had Cliffy, Petey, and Bruce with me. It wasn’t just comfortable for us to be together in our group—it was necessary.

At the edge of the Bronx River, about four blocks from our homes, sat the Dutch houses, or the Dutchies. Built by Dutch settlers, they were ancient buildings, now dilapidated but not quite abandoned. Herman Wouk wrote about them in his novel “City Boy,” describing the surrounding territory as an area of “odorous heaps.” When we felt really daring, we would venture out to those ruins, which were populated by wayward kids and runaways—Boonies, we called them, because they lived on Boone Avenue. Wild plants grew along the riverbanks, including bamboo that kids would cut down and carve into knives, bows, and arrows. The Boonies lived in shacks, and the lore was that they had poison on the ends of their homemade weapons.

One day, I was on Bryant Avenue and saw the rest of the gang limping back from the Dutchies, looking defeated. Cliffy was covered in blood. He noticed the expression on my face and shouted, “It’s not me! It’s Petey’s blood!” Behind him was Petey, blood gushing from his wrist. They had been making their way down a hill when Cliffy suddenly screamed, “Look out, there’s a Boony there!” He shouted out a name that was notorious in the area at the time. Even now I can’t bring myself to say it. Cliffy had only been kidding, but the other kids scrambled in every direction. Unfortunately, Petey stumbled and fell, landing hard on something sharp and jagged that sliced through his left wrist. The cut was so deep that it went all the way down to the nerves. It was horrible, all because of a dumb prank.

The doctors eventually stitched Petey up, but in a botched way, so he couldn’t move his hand correctly. Cliffy always blamed himself for what happened.

I’m taking a bath in my grandparents’ apartment when I hear a rumbling in the alleyway downstairs. From five stories below, the voices reach up to my bathroom window:

“Sonny!”

“Hey, Pacchi!”

“Sonn‐ayyyyyyyy! ”

These are my friends calling to me. But something is preventing me from leaping out of the tub, throwing on my clothes, and joining them. I don’t mean my conscience; I mean my mother. She is telling me I am not allowed. She says it’s late and tomorrow is a school day and any boys who come to shout in the alley at that time of night aren’t the sort of boys I should be spending my time with, and, anyway, the answer is no.

I hate her for this. These friends are everything in my life that means something to me. And then one day I’m fifty‐two, looking in the vanity mirror at my face, fat with shaving cream, wondering whom I should thank in an acceptance speech for an award I’m about to receive. I think back to that moment in the bath, and I realize that I’m still here because of my mother. Of course, that’s who I have to thank. She’s the one who parried me away from a path that led to delinquency and violence, to the heroin that eventually killed Petey, Cliffy, and Bruce. I lost all three that way. I was not exactly under strict surveillance, but my mother paid attention to where I was. I believe she saved my life.

Pacino’s nicknames as a kid included Sonny, Pacchi, and Pistachio, because he liked pistachio ice cream.Photograph courtesy the author / Mark Scarola

I was lucky that I had people who were looking out for me, even if I didn’t always appreciate it at the time. One of those people was my junior-high teacher Blanche Rothstein, who selected me to read passages from the Bible at our student assemblies. I didn’t come from a particularly religious family. My mother had sent me to catechism class, and I wore a little white suit for my first Holy Communion, and that was it. But when I read from the Book of Psalms in a big booming voice—“He that walketh uprightly, and worketh righteousness, and speaketh the truth in his heart”—I could feel how powerful the words were.

Soon I was performing in school plays like “The Melting Pot,” a pageant celebrating the many nations whose people had contributed to the greatness of America. I was there to represent Italy, along with a ten‐year‐old girl with dark hair and olive skin. Our class put on “The King and I,” and I was cast as Louis, the son of the heroine, Anna. I sang a song with the kid who played the young Prince of Siam, about being puzzled by how grownups behaved. I didn’t take acting very seriously at that point—it was just a way to get out my energy, and especially to get out of classes. But I somehow became the guy that you simply had to have in these school productions.

In eighth grade, we put on “Home Sweet Homicide,” and I was cast as a kid who helps his widowed mother solve a murder at the house next door. Before I went onstage, someone told me that both my parents were in the audience. It threw me off. To this day, I don’t want to know who’s in the audience on opening night.

Still, I felt at home onstage. I liked that people were paying attention to me. Right after the show, my mother and my father, who was now an accountant living in East Harlem with a new wife and child, took me out to Howard Johnson’s, and we all toasted my success. A feeling of warmth and belonging came over me. It was probably the first time in my entire life that I saw my parents talking to each other pleasantly, not arguing about anything. At one point, my father even touched my mother’s hand with his own—was he flirting with her? It all felt so easy and natural.

When I was fifteen, a troupe of actors, as if out of some bygone century, came to the Bronx’s old Elsmere Theatre, on Crotona Parkway, to put on a production of “The Seagull,” by Anton Chekhov. The ornate theatre seated more than fifteen hundred people, and an audience of about fifteen came to see the play. Two of those audience members were my friend Bruce and me.

I don’t know how much of the play I really understood, with all its unrequited romances and the tragic character of Konstantin, but I was riveted by the performances. I saw myself in the lives of those fictional characters.

From then on, I started carrying Chekhov’s works around with me, amazed at the idea that I could have access to his writing whenever I wanted. I had just got into the High School of Performing Arts in Manhattan, and so had Cliffy, who had also acted in middle school and was very good. In the mornings, we’d ride the train together from the Bronx and emerge at Forty‐second Street and Broadway. For the four blocks we walked up to P.A., we were mesmerized by the tourists and gawkers. One day, as we turned a corner, I saw Paul Newman, the movie star, walk by with someone, and I thought to myself, Wow, he’s a real person, with real friends he talks to when there are no cameras around.

On one train ride, Cliffy’s thoughts were focussed on the teacher of our voice-and-speech class. She was an intelligent and sophisticated woman whose claim to fame was that she had dated Marlon Brando. Cliffy said to me, “I’m going to feel her breasts.” From the way he said it, it was clear this was something he had been thinking about for a while. I said, “What?” He said, “Watch. You’ll see.”

The class began that morning as it normally did, with the teacher giving us our lesson in her deep, resonant voice. Before long, Cliffy got up. He said something to her, I don’t know what, and suddenly the two of them were tussling. Then Cliffy reached his arms around her from the back, turned her around to face the class, and there he was, behind her, with both hands on her breasts. He looked at me and smiled.

This was the act of someone with no propriety, no limitations, and no conscience. Most of the students were silent. I broke into laughter, as did a classmate named John. It was just an involuntary reaction to the shock of what Cliffy had done. I loved Cliffy, but I was genuinely horrified by this trespass. John and I got tossed out of the classroom for the day, which I spent in the principal’s office until my mother arrived and apologized on my behalf. Cliffy was thrown out of school, and then thrown out of his house. After that, he disappeared from my life for a while.

One afternoon, I went out for lunch at a coffee shop near school, and there, taking orders behind the counter, was one of the actors from the performance of “The Seagull” that I had seen in the Bronx. I was a little bit starstruck, and I said, “I saw you the other night! Oh, my God, you were so great!” I couldn’t believe I was talking to him. He seemed pleased to have a doting fan.

By day, he wore a waiter’s outfit, and by night he performed in a play. One was a job, and the other was his artistic calling. He was an actor moving from role to role and theatre to theatre, like actors have done for hundreds of years. This was how I came to understand acting as a profession. You did whatever work paid you so you could keep acting, and, if you could find a way to actually get paid for acting someday, all the better.

Just before I turned sixteen, my mother started seeing someone new. She would say to me, “You know, we may live in Texas or Florida,” meaning her and her husband‐to‐be. I was relieved in a way, but I didn’t see how I belonged in this arrangement. This man was around fifty; I thought, This guy probably doesn’t want me around, plus I wanted the apartment to myself. By now, my grandparents had moved farther uptown, to an apartment on 233rd Street, so it was just me and my mother living on Bryant Avenue.

Then their engagement was abruptly cancelled. The guy didn’t even have the decency to tell her in person. He sent her a telegram saying that he couldn’t go through with it. When she received it, she was sitting at our kitchen table, and I was leaning against the arch of our hallway. Four feet away was the door, which I was always aiming for.

When she told me the engagement was off, I actually said to her, “I knew that was too good to be true.” It was one of the most terrible things I ever said to her. How could I have? It bothered me that she was hurt. But it also bothered me that she wasn’t leaving.

My mother did not react well to the breakup. She was diagnosed with what the doctors called anxiety neurosis. She needed electroshock treatment and barbiturates. These were costly things that we didn’t have the money for. She encouraged me to quit school and go to work.

I stayed in school until I was sixteen, when I was legally old enough to quit. I was O.K. with it—I had never seen school as my place. At one point, P.A. had picked me to represent the student body in a photo accompanying an article in the New York Herald Tribune. At the last minute, I was replaced with another student, who was a dancer. She was tall and had red hair; I had my dark complexion and my Italian name. It crossed my mind that she represented a more mainstream version of beauty than I did; you didn’t see people like me in detergent commercials or on soap operas. But I didn’t think the school was being biased. Performing Arts was just trying to draw in more students, and this was the status quo at the time.

After I left, I went through various jobs, all short-lived. I spent a summer as a bicycle messenger. At seventeen, I had a successful stretch working for the American Jewish Committee and their magazine, Commentary. I said to the woman who interviewed me for the job, “I love sitting around offices. I love the sound of typewriters. I love switchboards.” I’m sure she saw right through my bullshit, but she hired me anyway. The people who worked there—people like Susan Sontag and Norman Podhoretz—were intellectual heavyweights, and, though they were very welcoming toward me, I never felt like I fit in. But, at an office party with a drink in my hand, I’d be able to talk to almost anyone.

At eighteen, I was nursing a fifteen‐cent beer at Martin’s Bar and Grill, on Twenty‐third Street and Sixth Avenue in Manhattan. It was a place where I’d sometimes go and have ketchup sandwiches: two saltine crackers with ketchup in the middle. The bar had a big picture window that looked across Sixth Avenue, where I could see the Herbert Berghof Studio, an acting school I was trying to get into. A friend had told me about the school, and a great teacher there named Charlie Laughton. I said, “The actor Charles Laughton?” He said, “No, no, different guy—his name is Charlie Laughton. He teaches sensory work.” I thought, I’m lost already.

I was pondering this when suddenly the bartender, who went by Cookie, got an angry look on his face. He got out from behind the bar and banged on the door of the men’s room. The next thing you know, he had hold of two scruffy young women by the collars of their leather jackets, and he was throwing them out. Cookie returned to his post at the bar, where seven or eight working stiffs were lined up, and the two women stood in front of that big, wide window in broad daylight and began passionately kissing. They were doing it so that everybody in the bar could see them. There was a rift I was witnessing right there between two separate worlds: the brazen young women outside who were the very essence of liberation, and the guys at the bar who were shell‐shocked by something they’d never seen in their lives. The sixties were coming.

I was introduced to Charlie Laughton at that same bar sometime later. The moment I set eyes on him, I thought, This guy is my kind of guy. He was about ten years older than me. He loved the poetry of William Carlos Williams, who came from Paterson, New Jersey, like he did. I enrolled at the Herbert Berghof Studio. I had no money, so I cleaned the hallways and the rooms where they had dance classes, and they gave me a scholarship.

By then, my mother had moved up to 233rd Street to live with her parents, and I had our apartment to myself. The rent was still thirty-eight dollars and eighty cents a month. But I had lost the Commentary job and I was broke. Charlie, who was married to an actress named Penny Allen, was broke, too, so he and I worked together as moving men. We moved office furniture and a lot of books. Our friend Matt Clark, who was in Charlie’s acting class, ran the moving operation. How does an actor prepare? He carries a refrigerator up the stairs.

In my free time, I became a voracious reader. Charlie turned me on to many novelists and poets I didn’t know. He would suggest various writers to check out and places to go, like the Forty‐second Street library for warmth and the Automat for sustenance. At the Automat, I could make a single cup of coffee last all morning, sitting there for five hours while I read my little books by the great authors. I would be reading “A Moveable Feast” and thinking, I don’t want to finish the pages, I like it here too much.

If the hour was late and you heard someone in your alleyway with a bombastic voice shouting iambic pentameter into the night, that was probably me, training myself on the famous Shakespeare soliloquies. I would bellow out monologues as I rambled through the streets of Manhattan. I’d do it by the factories, at the edges of town, places where no one was around. On those side streets, I didn’t need anyone’s permission to play Prospero, Falstaff, Shylock, or Macbeth. I grew to love Hamlet’s rogue-and-peasant-slave monologue so much that I started to use it at auditions. I would say to the director, “I know you have your pages that you want me to perform, but I have a little something that I’ve already prepared, if you don’t mind.” Usually they would give me a look that told me they were already finished with me.

Another young actor in Charlie’s class was a guy by the name of Martin Sheen. In one session, Marty did a monologue from “The Iceman Cometh,” and he blew the roof off. He was the next James Dean, as far as I was concerned. I got to be friends with him, and one day he said, “You know what my real name is, don’t you? Estevez.” He was half Spanish, and he came from Ohio, where he had a tough upbringing. He was one of ten kids in a working‐class family that was always struggling for money. He had tenacity and grit, and I could tell he was one of the best people I’d ever know.

Marty moved in with me in the South Bronx so we could split the rent. We worked together at the Living Theatre in Greenwich Village, where we cleaned toilets and laid down rugs for sets. The Living Theatre had been founded by Judith Malina and Julian Beck, two actors who started it in their living room in the nineteen-forties and eventually moved it to Fourteenth Street and Sixth Avenue. They did the kind of shows that made you go home afterward and lock yourself in your room and cry for two days, staring at the ceiling. They helped forge Off Broadway theatre, whose success paved the way for Off Off Broadway, which made possible some of the shows I was doing Off Off Off Off Broadway. When I appeared in “Hello Out There,” by William Saroyan, we would put on sixteen performances a week at Caffe Cino on Cornelia Street, and then we’d pass the hat to what little audience was there, hoping to come away with a few dollars for a meal. It was our Paris in the early nineteen-hundreds, our Berlin in the nineteen-twenties. That was the spirit of the scene.

The author, far right, with family in the South Bronx, including his grandfather, James Gerardi, far left, and his mother, Rose Gerardi Pacino, second from right.Photograph courtesy the author / Mark Scarola

Sometimes one of Marty’s brothers would stay over at the Bronx apartment, or this guy Sal Russo from acting class who was going with a woman named Sandra. Her best friend was a musician with long dark hair and piercing eyes named Joan Baez, who would occasionally drop in, sit cross‐legged in a corner, and play her guitar. She hadn’t linked up with Bob Dylan yet, but we knew Joan was going places. I don’t believe she and I even exchanged hellos.

I heard that Cliffy was back in the neighborhood again. Both he and Bruce had enlisted in the Army. Bruce made it as far as his induction ceremony, when he got second thoughts and threatened to jump out a window, so they let him go. Cliffy, on the other hand, served for a few months, but of course he got in trouble and was thrown into the brig before being discharged. I knew there was no risk that I’d be drafted myself, because I was supporting my mother. Anyway, could you imagine me, that boy I was, going around saying, “Hup‐two‐three‐four”? I can do it in a play.

Cliffy had come out of the Army in even worse shape than he went in. He was on the needle and doing and saying all kinds of crazy stuff. He said he had been in the same platoon as Elvis Presley, and it turned out he actually had. He said he went to Canada, got a Catholic girl pregnant, and converted from Judaism so that he could marry her. Every time he stopped by my apartment, he would go into the bathroom to shoot up, sometimes alone and sometimes in the company of other people he’d brought. Eventually I had to tell Cliffy he couldn’t come around anymore.

It was no surprise to anyone when he overdosed and died. It made me think of a story that he had told me. When he was in the brig, Cliffy said, he was watched by a guard, a Southerner who carried a .45 pistol. The guard would hold his pistol up just so and start saying ominous things about “the Jews.” In his Southern drawl, he would tell Cliffy, who was still Jewish at the time, “You know, I could just blow your head off and tell people you tried to escape. Would that be something to do?” He kept repeating it, day after day, until Cliffy finally turned to the guy and said, “Hey, man, you know what? You better kill me. Because if you don’t, when I get out of here, I’m gonna come back and kill you.” Cliffy may not have been the toughest guy I ever met, but he certainly was the most fearless.

It was Bruce who told me that my mother had overdosed. I came back to my apartment late one night to find a note on my door, saying that he had an urgent message for me. I went to his place; he lived with his parents in the building next door, and he took me into their kitchen and said, “Your mom’s in a lot of trouble. She’s really sick. You better go, man.” I jumped in a cab to 233rd Street.

Arriving at the building, I looked up and saw the lights on in my grandparents’ apartment. I went up the stairs, walked in the door, and there were my grandmother and grandfather, their eyes wet with tears. I was too late. My mother had died like Tennessee Williams would, choking while taking her own pills.

Some people thought that she had committed suicide, as she had tried to almost fifteen years earlier. But she left no note this time, nothing. She was just gone. That’s why I have always kept a question mark next to her death.

I’ll never forget the image of my grandfather the next morning, sitting in a folding chair in the middle of the room, nothing around him, crouched over with his head in his hands, almost between his legs. He just kept banging a foot on the floor. I’d never seen him that way. He didn’t speak, but I knew what he was saying. No.

I thought that maybe somehow I could have stopped it from happening. Therapy, financial security—these things could have helped my mother. I had known that one day I was going to be able to supply her with all that and more. It sounds like an Odets play, but it’s true.

here. Come with me.” I was stunned. But I didn’t go. I had moved out of the Bronx by that time and found a low‐rent rooming house in Chelsea for eight bucks a week. Something was driving me. I had to make it, because that was the only way I would survive this world. ♦

This is drawn from “Sonny Boy: A Memoir.”Published in the print edition of the September 2, 2024, issue, with the headline “Early Scenes.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reggie Rock Bythewood (July 7, 1967) is a filmmaker and actor. He is known for directing the film Dancing in September (2000) and creating the television series Shots Fired and Swagger.

He grew up in The Bronx. He was a rapper in a neighborhood hip-hop crew. During assemblies in junior high school, he and other schoolmates were allowed to get on stage and break dance.

After junior high, his main focus became acting. He went to the High School of Performing Arts as a drama major. The school did not allow students to work as professional actors.

During his senior year, he was cast in the soap opera Another World, he left Performing Arts and attended Quintanos School for the Young Professionals.

He acted in The Brother from Another Planet. He graduated from Marymount Manhattan College with a BFA in theater. He co-founded a New York City-based theater company called The Tribe which performed plays written and directed by him.

He moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career in screenwriting. He became one of the first members of Walt Disney’s prestigious Writers Fellowship Program. He was hired as a writer on A Different World. He went on to write and produce New York Undercover. He wrote the screenplay for Get on the Bus. He was one of the film’s investors.

He was hired to do the rewrite for Notorious. He made his feature film directorial debut on Dancing in September. He has directed Biker Boyz, “Daddy’s Girl”, “One Night in Vegas”, and Gun Hill, which he won the 2014 NAACP Image Award for. He co-created Shots Fired with Gina Prince-Bythewood.

He was chairman of the B-Dads organization. He fed homeless families in Los Angeles, raised thousands of dollars for the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation, and conducted workshops on fatherhood. He has spoken on various panels regarding police reform such as the annual convention for the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement.

He is married to filmmaker Gina Prince-Bythewood and they have two sons. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read-Alike Friday: King of the Armadillos by Wendy Chin-Tanner

King of the Armadillos by Wendy Chin-Tanner

Victor Chin’s life is turned upside down at the tender age of 15. Diagnosed with Hansen’s disease, otherwise known as leprosy, he’s forced to leave the familiar confines of his father’s laundry business in the Bronx – the only home he’s known since emigrating from China with his older brother – to quarantine alongside patients from all over the country at a federal institution in Carville.

At first, Victor is scared not only of the disease, but of the confinement, and wants nothing more than to flee. Between treatments he dreams of escape and imagines his life as a fugitive. But soon he finds a new sense of freedom far from home – one without the pull of obligations to his family, or the laundry business, or his mother back in China. Here, in the company of an unforgettable cast of characters, Victor finds refuge in music and experiences first love, jealousy, betrayal, and even tragedy. But with the promise of a life-changing cure on the horizon, Victor’s time at Carville is running out, and he has some difficult choices to make.

Stealing by Margaret Verble

Since her mother’s death, Kit Crockett has lived with her grief-stricken father, spending lonely days far out in the country tending the garden, fishing in a local stream, and reading Nancy Drew mysteries from the library bookmobile. One day when Kit discovers a mysterious and beautiful woman has moved in just down the road, she is intrigued.

Kit and her new neighbor Bella become fast friends. Both outsiders, they take comfort in each other’s company. But malice lurks near their quiet bayou and Kit suddenly finds herself at the center of tragic, fatal crime. Soon, Kit is ripped from her home and Cherokee family and sent to Ashley Lordard, a religious boarding school. Along with the other Native students, Kit is stripped of her heritage, force-fed Christian indoctrination, and is sexually abused by the director. But Kit, as strong-willed and shrewd as ever, secretly keeps a journal recounting what she remembers - and revealing just what she has forgotten. Over the course of Stealing, she slowly unravels the truth of how she ended up at the school - and plots a way out.

Beyond That, the Sea by Laura Spence-Ash

As German bombs fall over London in 1940, working-class parents Millie and Reginald Thompson make an impossible choice: they decide to send their eleven-year-old daughter, Beatrix, to America. There, she’ll live with another family for the duration of the war, where they hope she’ll stay safe.

Scared and angry, feeling lonely and displaced, Bea arrives in Boston to meet the Gregorys. Mr. and Mrs. G, and their sons William and Gerald, fold Bea seamlessly into their world. She becomes part of this lively family, learning their ways and their stories, adjusting to their affluent lifestyle. Bea grows close to both boys, one older and one younger, and fills in the gap between them. Before long, before she even realizes it, life with the Gregorys feels more natural to her than the quiet, spare life with her own parents back in England.

As Bea comes into herself and relaxes into her new life - summers on the coast in Maine, new friends clamoring to hear about life across the sea - the girl she had been begins to fade away, until, abruptly, she is called home to London when the war ends.

Desperate as she is not to leave this life behind, Bea dutifully retraces her trip across the Atlantic back to her new, old world. As she returns to post-war London, the memory of her American family stays with her, never fully letting her go, and always pulling on her heart as she tries to move on and pursue love and a life of her own.

A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power

Sissy, born 1961: Sissy’s relationship with her beautiful and volatile mother is difficult, even dangerous, but her life is also filled with beautiful things, including a new Christmas present, a doll called Ethel. Ethel whispers advice and kindness in Sissy’s ear, and in one especially terrifying moment, maybe even saves Sissy’s life.

Lillian, born 1925: Born in her ancestral lands in a time of terrible change, Lillian clings to her sister, Blanche, and her doll, Mae. When the sisters are forced to attend an “Indian school” far from their home, Blanche refuses to be cowed by the school’s abusive nuns. But when tragedy strikes the sisters, the doll Mae finds her way to defend the girls.

Cora, born 1888: Though she was born into the brutal legacy of the “Indian Wars,” Cora isn’t afraid of the white men who remove her to a school across the country to be “civilized.” When teachers burn her beloved buckskin and beaded doll Winona, Cora discovers that the spirit of Winona may not be entirely lost...

#historical fiction#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#library books#tbr#tbr pile#to read#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog#readers advisory

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

( young aaron paul, he/him, cismale ) i’m pretty sure i just ran into riley gibson! you know them, they’re the 29 year old mechanic that’s been here for 6 years. they can be pretty laidback, but on the d.l., they’re also flippant. i have their ringtone set as clint eastwood by gorillaz in my cell. next time you’re around the bronx, tell them to give me a call! ( kirby, 24, she/her, cst )

hey y'all, i'm kirby! thanks for joining our little group :') here's my little mid 2000s king

stats!

name: riley glenn gibson

d.o.b.: may 23rd, 1975

hometown: carson city, nv

current residence: brooklyn, nyc

height: 5'8" (5'10" according to him)

sexuality: heterosexual