#michael o'haughey

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Chicago at Long Beach, LA, 1992: A Story of Bebe Neuwirth, Choreography, Riots, Revivals, and Relevance

Recently and rather excitingly, more footage made its way to YouTube of the 1992 version of Chicago staged at Long Beach in LA, featuring Bebe Neuwirth as Velma and Juliet Prowse as Roxie.

Given its increased accessibility and visibility, this foregrounds the chance to talk about the show, explore some of its details, and look at the part it might have played as a contribution to the main ‘revival’ of Chicago in 1996 – which has given the show one of the most resonant and highly enduring legacies seen within the theatre ever.

This Civic Light Opera production at Long Beach was staged in 1992, four years before the ‘main’ revival made its appearance at Encores! or had its subsequent Broadway transfer, and it marked the first time a major revival of Chicago had been seen since the original 1975 show disappeared nearly 15 years previously.

This event is of particular significance given its position as the first step in the chain of events that make up part of this ‘new Chicago’ narrative and the resultant entire multiple-decade spanning impact of the show hereafter.

But for all of its pivotal status, it’s seldom discussed or remembered anywhere near as much as it should be.

This may be in part because of how little video or photographic record has remained in easily accessible form to date, and also because it only played for around two weeks in the first place. As such, it is a real treat on these occasions to get to see such incredible and unique material that would otherwise have been lost forever after such a brief existence some 30 years ago.

This earlier revival of the show still feels like what we have come to identify “Chicago” as in modern comprehension of the musical, most principally because the choreography was also done by Ann Reinking. As with the 1996 production, this meant dance was done “very much in the master’s style” – or Mr Bob Fosse.

The link below is time-stamped to Bebe and Juliet performing ‘Hot Honey Rag’. As one of the most infamous numbers in Broadway history, it’s undoubtedly a dance that has been watched many times over. But never before have I seen it done quite like this.

https://youtu.be/4HKkwtRE-II?t=2647

‘Hot Honey Rag’ was in fact formerly called ‘Keep It Hot’, and was devised by Fosse as “a compendium of all the steps he learned as a young man working in vaudeville and burlesque—the Shim Sham, the Black Bottom, the Joe Frisco, ‘snake hips,’ and cooch dancing”, making it into the “ultimate vaudeville dance act” for the ultimate finale number.

Ann would say about her choreographical style in relation to Fosse, “The parts where I really deviate is in adding this fugue quality to the numbers. For better or worse, my style is more complicated.” The ��complexity’ and distinctness she speaks of is certainly evident in some of the sections of this particular dance. There are seemingly about double the periodicity of taps in Bebe and Juliet’s Susie Q sequence alone. One simply has to watch in marvel not just at the impressive synchronicity and in-tandem forward motion, but now also at the impossibly fast feet. Other portions that notably differ from more familiar versions of the dance and thus catch the eye are the big-to-small motion contrast after the rising ‘snake hips’ section, and all of the successive goofy but impeccably precise snapshot sequence of arm movements and poses.

More focus is required on the differences and similarities of this 1992 production compared against the original or subsequent revival, given its status and importance as a bridging link between the two.

The costumes in 1975 were designed by Patricia Zipprodt (as referenced in my previous post on costume design), notably earning her a Tony Award nomination. In this 1992 production, some costumes were “duplications” of Zipprodt’s originals, and some new designs by Garland Riddle – who added a “saucy/sassy array” in the “typical Fosse dance lingerie” style. It is here we begin to see some of the more dark, slinkiness that has become so synonymous with “Chicago” as a concept in public perception.

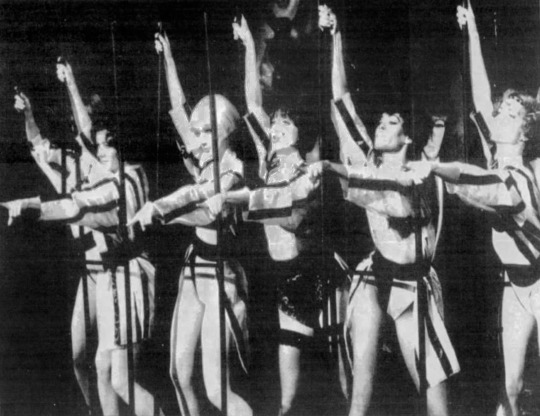

The sets from the original were designed by Tony Walton – again, nominated for a Tony – and were reused with completeness here. This is important as it shows some of the original dance concepts in their original contexts, given that portions of the initial choreography were “inextricably linked to the original set designs.” This sentiment is evident in the final portion of ‘Cell Block Tango’, pictured and linked at the following time-stamp below, which employs the use of mobile frame-like, ladder structures as a scaffold for surrounding movements, and also a metaphor for the presence of jail cell bars.

https://youtu.be/4HKkwtRE-II?t=741

Defining exactly how much of the initial choreography was carried across is an ephemeral line. Numbers were deemed “virtually intact” in the main review published during the show’s run from the LA Times – or even further, “clones” of the originals. It is thought that the majority of numbers here exhibit greater similarity to the 1975 production than the 1996 revival, except for ‘Hot Honey Rag’ which is regarded as reasonably re-choreographed. But even so, comparing against remaining visible footage of Gwen Verdon and Chita Rivera from the original, or indeed alternatively against Bebe and Annie later in the revival, does not present an exact match to either.

This speaks to the adaptability and amorphousness of Fosse-dance within its broader lexicon. Fosse steps are part of a language that can be spoken with subtle variations in dialect. Even the same steps can appear slightly different when being used in differing contexts, by differing performers, in differing time periods.

It also speaks to some of the main conventions of musical theatre itself. Two main principles of the genre include its capacity for fluidity and its ability for the ‘same material’ to change and evolve over time; as well as the fact comparisons and comprehensions of shows across more permanent time spans are restricted by the availability of digital recordings of matter that is primarily intended to be singular and live.

Which versions of the same song do you want to look at when seeking comparisons?

Are you considering ‘Hot Honey Rag’ at a performance on the large stage at Radio City Music Hall at the Tony Awards in 1997? Or on a small stage for TV shows, like the Howard Cosell or Mike Douglas shows in 1975? Or on press reel footage from 1996 on the ‘normal’ stage context in a format that should be as close to a replica as possible of what was performed in person every night?

Bebe often remarks on and marvels at Ann’s capacity to travel across a stage. “If you want to know how to travel, follow Annie,” she says. This exhibits how one feature of a performance can be so salient and notable on its own, and yet so precariously dependent on the external features its constrained to – like scale.

Thus context can have a significant impact on how numbers are ultimately performed for these taped recordings and their subsequent impact on memory. Choreography must adjust accordingly – while still remaining within the same framework of the intention for the primary live performances.

This links to Ann’s own choreographical aptitude, in the amount of times it is referenced how she subtly adapted each new version of Chicago to tailor to individual performers’ specific merits and strengths as dancers.

Ann’s impact in shaping the indefinable definability of how Chicago is viewed, loved and remembered now is not to be understated.

An extensive 1998 profile – entitled “Chicago: Ann Reinking’s musical” – explores in part some of Ann’s approaches to creating and interacting with the material across a long time span more comprehensively. Speaking specifically to how she choreographed this 1992 production in isolation, Ann would say, “I knew that Bob’s point of view had to permeate the show, you couldn’t do it without honoring his style.” In an age without digital history at one’s fingertips, “I couldn’t remember the whole show. So I choreographed off the cuff and did my own thing. So you could say it was my take on his thoughts.” Using the same Fosse vocabulary, then – “it’s different. But it’s not different.”

One further facet that was directly carried across from the initial production were original cast members, like Barney Martin as returning as Amos, and Michael O'Haughey reprising his performance as Mary Sunshine. Kaye Ballard as Mama Morton and Gary Sandy as Billy Flynn joined Bebe and Juliet to make up the six principals in this new iteration of the show.

Bebe, Gary and Juliet can be seen below in a staged photo for the production at the theatre.

The venue responsible for staging this Civic Light Opera production was the Terrace Theatre in Long Beach in Los Angeles. Now defunct, this theatre and group in its 47 years of operation was credited as providing some of “the area’s most high profile classics”. Indeed, in roughly its final 10 years alone, it staged shows such as Hello Dolly!, Carousel, Wonderful Town (with Donna McKechnie), Gypsy, Sunday in the Park with George, La Cage aux Folles, Follies, 1776, Funny Girl, Bye Bye Birdie, Pal Joey, and Company. The production of Pal Joey saw a return appearance from Elaine Stritch, reprising her earlier performance as Melba Snyder with the memorable song ‘Zip’. This she had done notably some 40 years earlier in the original 1952 Broadway revival, while infamously and simultaneously signed as Ethel Merman’s understudy in Call Me Madam as she documented in Elaine Stritch at Liberty.

Juliet Prowse appeared as Phyllis in Follies in 1990, and Ann Reinking acted alongside Tommy Tune in Bye Bye Birdie in 1991, in successive preceding seasons before this Chicago was staged.

But for all of its commendable history, the theatre went out of business in 1996 just 4 years after this, citing bankruptcy. Competition provided in the local area by Andrew Lloyd Webber and his influx of staging’s of his British musicals was referenced as a contributing factor to the theatre group’s demise. This feat I suspect Bebe would have lamented or expressed remorse for, given some of her comments in previous years on Sir Lloyd Webber and the infiltration of shows from across the pond: “I had lost faith in Broadway because of what I call the scourge of the British musicals. They've dehumanized the stage [and] distanced the audience from the performers. I think 'Cats' is like Patient Zero of this dehumanization.”

That I recently learned that Cats itself can be rationalised in part as simply A Chorus Line with ears and tails I fear would not improve this assessment. In the late ‘70s when Mr Webber noticed an increase of dance ability across the general standard of British theatre performers, after elevated training and competition in response to A Chorus Line transferring to the West End, he wanted to find a way he could use this to an advantage in a format that was reliable to work. Thus another similarly individual, sequential and concept-not-plot driven dance musical was born. Albeit with slightly more drastic lycra leotards and makeup.

But back in America, the Terrace theatre could not be saved by even the higher incidence of stars and bigger Broadway names it was seeing in its final years, with these aforementioned examples such as Bebe, Annie, Tommy, Juliet, Donna, or Elaine. The possibility of these appearances in the first place were in part attributable to the man newly in charge as the company’s producer and artistic director – Barry Brown, Tony award-winning Broadway producer.

Barry is linked to Bebe’s own involvement with this production of Chicago, through his relationship – in her words – as “a friend of mine”.

At the time, Bebe was in LA filming Cheers, when she called Barry from her dressing room. Having been working in TV for a number of years, she would cite her keenness to find a return to the theatre, “[wanting] to be on a stage so badly” again. The theatre is the place she has long felt the most sense of ease in and belonging for, frequently referring to herself jokingly as a “theatre-rat” or remarking that it is by far the stage that is the “medium in which I am most comfortable, most at home, and I think I'm the best at.”

Wanting to be back in that world so intensely, she initially proposed the notion of just coming along to the production to learn the parts and be an understudy. Her desire to simply learn the choreography alone was so strong she would say, “You don’t have to pay me or anything!”

She’d had the impetus to make the call to Barry in the first place only after visiting Chita Rivera at her show in LA with a friend, David Gibson. At the time, the two did not know each other that well. Bebe had by this point not even had the direct interaction of taking over in succession for Chita in Kiss of the Spider Woman in London. This she would do the following year, with Chita guiding her generously through the intricacies of the Shaftesbury Theatre and the small, but invaluable, details known only to Chita that would be essential help in meeting stage cues and playing Aurora.

Bebe had already, however, stepped into Chita’s shoes multiple times, as Anita in West Side Story as part of a European tour in the late ‘70s, or again in a Cleveland Opera Production in 1988; and additionally as Nickie in the 1986 Broadway revival of Sweet Charity – both of which were roles Chita had originated on stage or screen. In total, Velma would bring the tally of roles that Bebe and Chita have shared through the years to four, amongst many years also of shared performance memories and friendship.

They may not have had a long history of personal rather than situational connections yet when Bebe visited her backstage at the end of 1991, but Chita still managed to play a notable part in the start of the first of Bebe’s many engagements with Chicago.

After Bebe hesitantly relayed her idea, Chita told her, “You should call! Just call!”

So call Bebe did. One should listen to Chita Rivera, after all.

Barry Brown rang her back 10 minutes later after suggesting the idea to Ann Reinking, who was otherwise intended to be playing Velma. The response was affirmative. “Oh let her play the part!”, Annie had exclaimed. And so begun Bebe’s, rather long and very important, journey with Chicago.

In 1992, this first step along the road to the ‘new Chicago’ was well received.

Ann Reinking with her choreography was making her first return to the Fosse universe since her turn in the 1986 Sweet Charity revival. Diametrically, Rob Marshall was staring his first association with Fosse material in providing the show’s direction – many years before he would go on to direct the subsequent film adaptation also. Together, they created a “lively, snappy, smarmy” show that garnered more attention than had been seen since the original closed.

“Bob Fosse would love [this production],” it was commended at the time, “Especially the song-and-dance performance of Bebe Neuwirth who knocks everyone’s socks off.” High praise.

Bebe was also singled out for her “unending energy”, but Juliet too received praise in being “sultry and funny”. Together, the pair were called “separate but equal knockouts” and an “excellent combination”.

Juliet was 56 at the time, and sadly died just four years later. Just one year after the production though, Juliet was recorded as saying, “In fact, we’re thinking of doing it next year and taking it out on the road.”

Evidently that plan never materialised. But it is interesting to note the varied and many comments that were made as to the possibility of the show having a further life.

Bebe at the time had no recollection that the show might be taken further, saying “I didn’t know anything about that.” Ann Reinking years later would remark “no one seemed to think that the time was necessarily ripe for a full-blown Broadway revival.” While the aforementioned LA Times review stated in 1992 there were “unfortunately, no current plans” for movement, it also expressed desire and a call to action for such an event. “Someone out there with taste, money and shrewdness should grab it.”

The expression that a show SHOULD move to Broadway is by no means an indication that a show WILL move. But this review clearly was of enough significance for it to be remembered and referenced by name by someone who was there when it came out at the time, Caitlin Carter, nearly 30 years later. Caitlin was one of the six Merry Murderesses, principally playing Mona (or Lipschitz), at each of this run, Encores!, and on Broadway. She recalled, “Within two days, we got this rave review from the LA Times, saying ‘You need to take the show to Broadway now!’” The press and surrounding discussions clearly created an environment in which “there was a lot of good buzz”, enough for her to reason, “I feel like it planted seeds… People started to think ‘Oh we need to revive this show!’”

The seeds might have taken a few years to germinate, but they did indeed produce some very successful and beautiful flowers when they ultimately did.

In contrast with one of the main talking points of the ‘new Chicago’ being its long performance span, one of the first things I mentioned about this 1992 iteration was the rather short length of its run. It is stated that previews started on April 30th, for an opening on May 2nd, with the show disappearing in its final performance on May 17th. Less than a fleeting 3 weeks in total.

Caitlin Carter discussed the 1992 opening on Stars in the House recently. It’s a topic of note given that their opening night was pushed back from the intended date by two days, meaning Ann Reinking and Rob Marshall had already left and never even saw the production. “The night we were supposed to open in Long Beach was the Rodney King riots.”

Local newspapers at the time when covering the show referenced this large and significant event, by noting the additional two performances added in compensation “because of recent interruptions in area social life.”

It sounds rather quaint put like that. In comparison, the horror and violence of what was actually going on can be statistically summated as ultimately leaving 63 people dead, over 2300 injured, and more than 12,000 having been arrested, in light of the aftermath of the treatment faced by Rodney King. Or more explicitly, the use of excessive violence against a black man at police hands with videotaped footage.

A slightly later published review wrote of how this staging was thus “timely” – in reference to an observed state of “the nation’s moral collapse”.

‘Timeliness’ is a matter often referenced when discussing why the 1996 revival too was of such success. The connection is frequently made as to how this time, the revival resonated with public sentiment so strongly – far more than in 1975 when the original appeared – in part because of the “exploding headlines surrounding the OJ Simpson murder case”. The resulting legal and public furore around this trial directly correlates with the backbone and heart of the musical itself.

I'm writing this piece now at the time of the ongoing trial to determine the verdict of George Floyd’s murder, another black man suffering excessive and ultimately fatal violence at police hands with videotaped footage.

I think the point is that this is never untimely. And that the nation is seldom not in some form of ‘moral collapse’, or facing events that have ramifications to do with the legal system and are emotionally incendiary on a highly public level.

Which perhaps is why Chicago worked so well not just in 1996, but also right up to the present day.

Undoubtedly, we live in a climate where the impact of events is determined not just by the events themselves, but also the manner in which they are reported in the media. Events involving some turmoil and public outrage at the state and outcome of the legal system are not getting any fewer or further between. But the emphasis on the media in an increasingly and unceasingly digital age is certainty only growing.

#chicago#chicago the musical#chicago musical#bebe neuwirth#juliet prowse#ann reinking#bob fosse#fosse#dance#broadway#musicals#theatre#theatre history#choreography#gwen verdon#chita rivera#long reads#writing#george floyd#rodney king#oj simpson#dancing#dancer#andrew lloyd webber#cats the musical#musical theatre

76 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Gwen Verdon and M. (Michael) O’Haughey on ‘To Tell the Truth,’ includes a performance by Mr. O’Haughey (the original Mary Sunshine from Chicago) singing “A Little Bit of Good.”

(via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lNF49hqr2qs)

0 notes