#like stefanos is a greek god that's a fact

Text

#they are so achilles and patroclus coded#like stefanos is a greek god that's a fact#and they are meant for each other but also bond on tragedy#someone please write a Stefaniil song of achilles fic like the ones that exist so far are not heart breaking enough already#stefaniil#stefanos tsitsipas#daniil medvedev#tennis#the song of achilles#aesthetic#books#fanfics#quotes#poetry

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

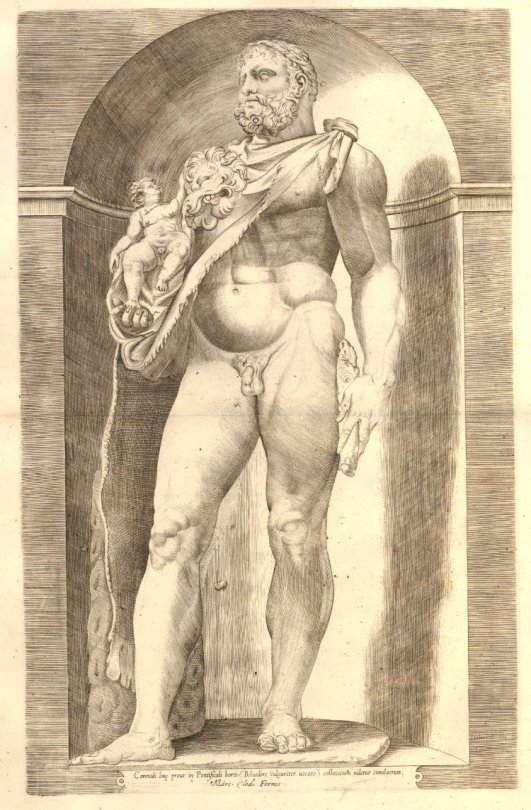

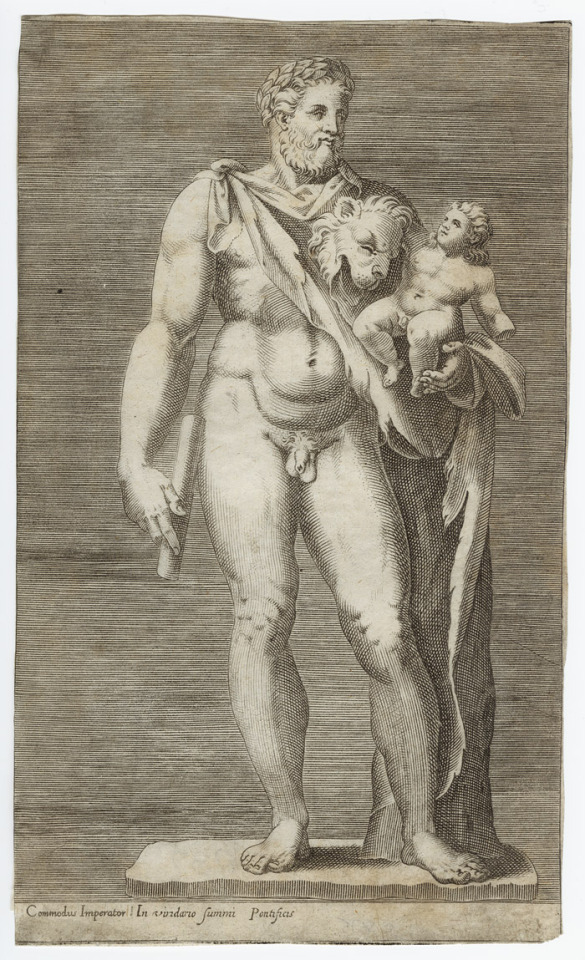

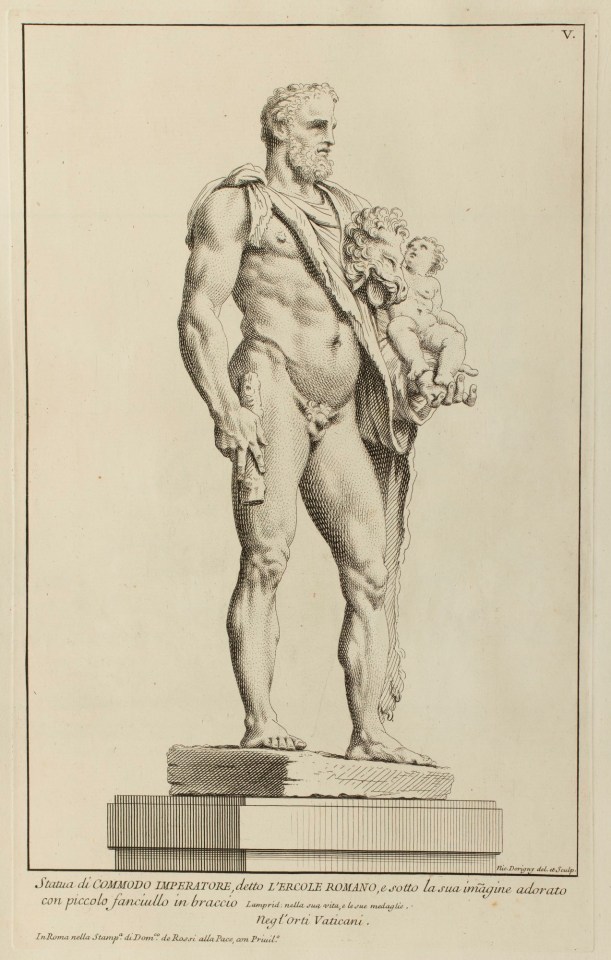

The Image of Hercules with infant Telephos

The statue of Heracles with infant Telephos which is located in the Chiaramonti Museum is the oldest example of this image, having been created in the 2nd century A.D. as a copy of a Greek statue of the 4th century A.D.

This statue, which was discovered in Rome in the vicinity of Campo de’ Fiori, was one of the first sculptures to come into the Vatican collections. Pope Julius II (1503-1573) exhibited it in the Courtyard of the Statues in the Belvedere. The presence of Heracles, in fact, leads us back to the mythological origins of Rome and alludes in particular to the victory of the Romans over the tribes of ancient Latium. The god Heracles, with his club and lion skin, holds his son Telephos in his arms. Telephos is the son born to Heracles by the priestess Auge who was forced to abandon the child in the mountains of Arcadia, where he was nourished by a doe until he was rescued by his father. Telephos became King of Mysia and one of the leading characters in a rich and complex mythology that sees him involved in the Greek expedition against Troy. This statue is a second century A.D. copy, probably of a Late Hellenistic original.

In The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates: Rome's Deadliest Enemy, Adrienne Mayor states that "Recent analysis of portraiture in contemporary coins and sculpture suggests that the model for the little boy was none other than Mithradates!"

According to her Pompey the Great recognized the likeness of the baby Telephus to Mithradates and took it to Rome after defeating Mithradates in 63 BC (Mayor): "Pompey installed this Hercules statue in his Theater on the Field of Mars in Rome. The statue was discovered in 1507 in Campo dei Fiori, near the ruins of Pompey's Theater."

After its rediscovery in 1507, the statue became an inspiration for the artists of its time leading to many engravings of the image belonging to the 16th century. The emperor Commodus was pictured in the same pose multiple times in the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae (published c. 1540-80), inspiring slightly different copies which dates extend into the 18th century. I am not sure if I have acquired all of these copies since there are so many. But here are some;

Emperor Commodus as Hercules, Attributed to Jacob(us) Bos, 1550

This print comes from the museum’s copy of the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae (The Mirror of Roman Magnificence) The Speculum found its origin in the publishing endeavors of Antonio Salamanca and Antonio Lafreri. During their Roman publishing careers, the two foreign publishers - who worked together between 1553 and 1563 - initiated the production of prints recording art works, architecture and city views related to Antique and Modern Rome. The prints could be bought individually by tourists and collectors, but were also purchased in larger groups which were often bound together in an album. In 1573, Lafreri commissioned a title page for this purpose, which is where the title ‘Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae’ first appears. Lafreri envisioned an ideal arrangement of the prints in 7 different categories, but during his lifetime, never appears to have offered one standard, bound set of prints. Instead, clients composed their own selection from the corpus to be bound, or collected a group of prints over time. When Lafreri died, two-third of the existing copper plates went to the Duchetti family (Claudio and Stefano), while another third was distributed among several publishers. The Duchetti appear to have standardized production, offering a more or less uniform version of the Speculum to their clients. The popularity of the prints also inspired other publishers in Rome to make copies however, and to add new prints to the corpus.

The Emperor Commodus dressed as Hercules, after an antique statue placed in a niche in the Belvedere, Anonymous, 1587-89

Hercules and Telephos, Hendrick Glotzius, c. 1592

Emperor Commodus in the Papal gardens, after the engraving of Jacob(us) Bos, ca. 1614

Heracles with infant Telephos, Sir Nicolas Dorigny, 1704

Of course, the statue’s artistic interpretations were not limited to engravings. Here is a terracotta reproduction by Stefano Maderno, dated 1620.

And lastly, I would like to add a very interesting photograph by James Anderson dating 1859 and bearing the name Hercule avec le jeune Ajax. It is a photograph of the sculpture we know today but with the father's genitals covered and the club still intact.

Image Sources:

1. http://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/museo-chiaramonti/ercole-e-telefo-bambino.html

2. https://www.flickr.com/photos/askrobotov/48448640202/

3. https://www.flickr.com/photos/hen-magonza/7361370584/

4. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/402935

5. https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?assetId=340981001&objectId=3064979&partId=1

6. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/112044/hercules-and-telephos-plate-two-from-three-famous-antique-sculptures

7. http://speculum.lib.uchicago.edu/search.php?search%5B0%5D=commodus&searchnode%5B0%5D=all&result=7

8. https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/heracles-with-infant-telephos-kown-as-commodo-imperatore-or-ercole-romano

9. shorturl.at/fgDJ9

10. http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/218216/james-anderson-hercule-avec-le-jeune-ajax-vatican-british-1859/?dz=0.4745,0.4745,0.74

#greek art#roman art#hellenistic#hercules#herakles#telephos#herakles and telephos#vatican#musei vaticani#vatican museums#sculpture

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

8th July >> (@ZenitEnglish By Virginia Forrester) #Pope Francis #PopeFrancis Pope Francis Addresses Members of Permanent Synod of Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church. Full Text of 5th July Talk to Group Gathered in Rome.

The Holy Father Francis received in audience this morning, in the Bologna Hall of the Apostolic Vatican Palace, the Members of the Permanent Synod of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church, and he gave the address, which we translate below.

* * *

The Holy Father’s Address

Beatitude, Dear Brother Major Archbishop,

Eminences, Excellencies,

Dear Brothers!

It was my wish to invite you here, to Rome, for a fraternal sharing, also with the Superiors of the competent Dicasteries of the Roman Curia. I thank you for accepting the invitation; it’s lovely to see you. Ukraine has been living for some time a difficult and delicate situation, for over five years wounded by a conflict that many call “hybrid,” made up as it is by war actions where those responsible blend with one another; a conflict where the weakest and littlest pay the highest price; a conflict aggravated by propagandist falsifications and manipulations of various sorts, including the attempt to involve the religious aspect.

I carry you in my heart and I pray for you, dear Ukrainian Brothers. And I confide to you that sometimes I do so with the prayer that I remember and that I learned from Bishop Stefano Chmil, then a Salesian priest. He taught it to me in 1949, when I was twelve, and I learned from him to serve the Divine Liturgy three times a week. I thank you for your fidelity to the Lord and to the Successor of Peter, often costing dearly in the course of history, and I entreat the Lord, so that He may accompany the actions of all political leaders to seek not the so-called one-sided good, which in the end is always an interest to the detriment of another, but the common good, peace. And I ask the “God of all comfort” (2 Corinthians 1:3) to comfort the spirit of those that have lost their dear ones because of the war, and those that bear wounds in the body and in the spirit, those that have had to leave their home and work and face the risk of seeking a more human future elsewhere and far away. Know that my gaze turns every morning and every evening to Our Lady, of which His Beatitude made me a gift when he left Buenos Aires to assume the office of Major Archbishop that the Church had entrusted to him. I begin and end the days before that icon, entrusting all of you and your Church to the tenderness of Our Lady, who is Mother. It can be said that I begin the days and end them “in Ukranian,” looking at Our Lady.

In the face of the complex situations caused by the conflicts, the principal role of the Church is to offer the witness of Christian hope. Not a hope of the world, which is based on things that pass, come and go, and often divide, but the hope that never disappoints, that does not yield to discouragement., which is able to overcome every tribulation in the gentle strength of the Spirit (Cf. Romans 5:2-5). Christian hope, nourished by the light of Christ, makes the resurrection and life shine even in the darkest nights of the world. Therefore, dear Brothers, I believe that, in difficult periods, even more so than in those of peace, the priority for believers is to be united to Jesus, our hope. It’s about renewing that union founded on Baptism and rooted in the Faith, rooted in the history of our communities, rooted in the great witnesses: I think of the array of daily heroes, of those numerous next-door saints that, with simplicity, have responded among your people to evil with good (Cf. Romans 12:21). They are the example to look at: those that in the meekness of the Beatitudes had the Christian courage of not opposing themselves to the wicked, of loving enemies and praying for persecutors (Cf. Mathew 5:39.44). In the violent field of history, they planted the Cross of Christ, and they have borne fruit. These brothers and sisters of yours, who have suffered persecutions and martyrdom and that, close to the Lord Jesus, rejected the logic of the world, according to which violence is answered with violence, have written with <their> life the most limpid pages of the faith: they are fecund seeds of Christian hope. I read with emotion the book “Persecuted for the Truth.” Behind those priests, Bishops, Sisters, is the People of God, which carries forward with faith and prayer the whole people.

Some years ago the Synod of Bishops of the Ukrainian Greed-Catholic Church adopted the pastoral program entitled “The Living Parish, Place of Encounter with the Living Christ. In some translations, the expression “Parrochia viva” was rendered with the adjective “vibrant.” In fact, the encounter with Jesus, the spiritual life, the prayer that vibrates in the beauty of your Liturgy transmit that beautiful strength of peace, which soothes wounds, infuses courage but not aggression. When, as from a well of spring water, we draw this spiritual vitality and transmit it, the Church becomes fecund. She becomes the Herald of the Gospel of hope, Teacher of that interior life that no other institution is able to offer.

Therefore, I wish to encourage you all, in as much as Pastors of the People of God, to have a primary concern in all your activities: prayer <and> the spiritual life. It’s the first occupation; no other goes before it. We know and all see that in your tradition you are a Church that is able to speak in spiritual, not worldly, terms (Cf. 1 Corinthians 2:13), because every person that approaches the Church needs Heaven on earth, nothing else. May the Lord grant you this grace and make us all dedicated to our sanctification and that of the faithful entrusted to us. In the night of conflict you are going through, as in Gethsemane, the Lord asks His own to “watch and pray”; not to defend themselves, and much less to attack. However, the disciples slept instead of praying and, when Judas arrived, they pulled out the sword. They hadn’t prayed and fell into temptation, in the temptation of worldliness: the violent weakness of the flesh prevailed over the meekness of the spirit. Not sleep, not the sword, not flight (Cf. Matthew 26:40.52.56), but prayer and the gift of self to the end are the answers that the Lord awaits from His own. Only these answers are Christian; they alone save one from the worldly spiral of violence.

The Church is called to carry out her pastoral mission with various means. After prayer comes closeness. What the Lord had asked His apostles that evening, to stay close to Him and to watch (Cf. Mark 14:34), He asks today of His Pastors: to be with the people, watching beside one going through the night of pain. The closeness of Pastors to the faithful is a channel, which is built day by day and which brings the living water of hope. It’s built thus, encounter after encounter, with the priests that know and take to heart the people’s concerns, and the faithful that, through the care they receive, assimilate the proclamation of the Gospel, which the Pastors transmit. They don’t understand it if the Pastors are only intent on saying God: they understand it if they spend themselves in giving God: giving themselves, being close, witnesses of the God of hope that made Himself flesh to walk on the roads of man. May the Church be the place where hope is drawn, where the door is always open, where consolation and encouragement is offered. Never closure towards anyone, but an open heart; never looking at the clock to send home one who needs to be listened to. We are servants in time. We live in time. Please, don’t fall into the temptation to live as slaves of the clock! –Time, not the clock.

Pastoral care includes in the first place the liturgy that, as the Major Archbishop has often stressed, together with spirituality and catechesis, constitutes an element that characterizes the identity of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church. She, to the world “still disfigured by egoism and greed, reveals the way towards the balance of the new man” (Saint John Paul II, Apostolic Letter Orientale Lumen, 11): the way of charity, of unconditional love, within which every other activity must be directed, to nourish the fraternal bond between persons, inside and outside of the community.

With this spirit of closeness, in 2016 I promoted a humanitarian initiative, to which I invited the Churches of Europe to take part, to offer help to those most affected by the conflict. I thank again from my heart all those that contributed to the carrying out of this collection, be it on the economic, be it on the organizational and technical plane. And to that first initiative, now essentially concluded, I would like other special projects to follow. Already in this meeting, some information could be provided. It’s so important to be close to all and to be concrete, also to avoid the danger of a grave situation of suffering falling into general oblivion. A suffering brother can’t be forgotten, regardless of where he comes from. A suffering brother can’ be forgotten.

I would like to add a third word to prayer and closeness, which is so familiar to you: synodality. To be Church is to be a community that walks together. It’s not enough to hold a Synod, it’s necessary to be Synod. The Church has need of intense internal sharing: a lively dialogue between Pastors and between Pastors and faithful. In as much as Oriental Catholic Church, you have already in your canonical order a marked Synodal expression, which foresees frequent and periodical recourse to assemblies of the Synod of Bishops. However, every day the Synod must be done, making an effort to walk together, not only with one who thinks the same way — this would be easy — but with all believers in Jesus. Three aspects revive synodality. First of all, listening: to listen to the experiences and the suggestions of Brother Bishops and Presbyters. It’s important that each one, inside the Synod, feels he is heard. To listen is all the more important the more one goes up in the hierarchy. Listening is sensitivity and openness to the opinion of brothers, also of those that are the youngest and also those considered less expert. A second aspect: co-responsibility. We can’t be indifferent in face of the errors and carelessness of others, without intervening in a fraternal but convinced way: our brothers have need of our thought, of our encouragement, as well as of our corrections, because, in fact, we are called to walk together. One can’t conceal what is not right and go on as if there were nothing to defend at all cost of one’s own good name: charity is always lived in truth, in transparency, in that Parrhesia that purifies the Church and makes her go forward. Synodality — <the> third aspect — also means involvement of the laity: in as much as full members of the Church, they are also called to express themselves, to give suggestions. Participants in ecclesial life, they are not only heard but listened to. And I underscore this verb: to listen. One who listens can then speak well; he who isn’t used to listening, doesn’t speak, he barks. Synodality also leads to widening the horizons, to living the richness of one’s tradition within the universality of the Church: to benefit from good relations with the other rites; to consider the beauty of sharing significant parts of one’s theological and liturgical treasure with other communities, also non-Catholic ones; to weave fruitful relationships with other particular Churches, as well as with the Dicasteries of the Roman Curia. The unity in the Church will be that much more fecund, the more agreement and cohesion there is between the Holy See and the particular Churches is real. More precisely: the more <there is> agreement and cohesion between all the Bishops with the Bishop of Rome. This must certainly not “entail a diminution in the awareness of one’s authenticity and originality” (Orientale Lumen, 21), but molded within our Catholic identity, that is, universal. In as much as universal, it is put in danger and can be worn down by attachment to the particularism of various sorts: ecclesial particularisms, nationalistic particularisms, political particularisms.

Dear Brothers, may these two days of the meeting, which I desired intensely, be intense moments of sharing, of mutual listening, of free dialogue, always animated by the search for the good, in the spirit of the Gospel. May they help us walk together better. In a certain sense, it’s a sort of Synod dedicated to the themes that are most at heart of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church in this period, marked by the still on-going military conflict and characterized by a series of political and ecclesial processes much more ample than those regarding our Catholic Church. However, I recommend this spirit to you, this discernment on which to verify yourselves: prayer and spiritual life in the first place; then closeness, especially with one that suffers; then synodality, walking together, walking openly, step after step, with meekness and docility. I thank you. I accompany you on this path and I ask you, please, to remember me in your prayers. Thank you!

[Original text: Italian] [ZENIT’s translation by Virginia M. Forrester]

© Libreria Editrice Vatican

8th JULY 2019 18:43EASTERN CHURCHES

0 notes

Text

LAW # 13 : WHEN ASKING FOR HELP, APPEAL TO PEOPLE’S SELF-INTEREST, NEVER TO THEIR MERCY OR GRATITUDE

JUDGMENT

If you need to turn to an ally for help, do not bother to remind him of your past assistance and good deeds. He will find a way to ignore you. Instead, uncover something in your request, or in your alliance with him, that will benefit him, and emphasize it out of all proportion. He will respond enthusiastically when he sees something to be gained for himself.

TRANSGRESSION OF THE LAW

In the early fourteenth century, a young man named Castruccio Castracani rose from the rank of common soldier to become lord of the great city of Lucca, Italy. One of the most powerful families in the city, the Poggios, had been instrumental in his climb (which succeeded through treachery and bloodshed), but after he came to power, they came to feel he had forgotten them. His ambition outweighed any gratitude he felt. In 1325, while Castruccio was away fighting Lucca’s main rival, Florence, the Poggios conspired with other noble families in the city to rid themselves of this troublesome and ambitious prince.

THE PEASANT AND THE APPLE-TREE

A peasant had in his garden an apple-tree, which bore no fruit, but only served as a perch for the sparrows and grasshoppers. He resolved to cut it down, and, taking his ax in hand, made a bold stroke at its roots. The grasshoppers and sparrows entreated him not to cut down the tree that sheltered them, but to spare it, and they would sing to him and lighten his labors. He paid no attention to their request, but gave the tree a second and a third blow with his ax. When he reached the hollow of the tree, he found a hive full of honey. Having tasted the honeycomb, he threw down his ax, and, looking on the tree as sacred, took great care of it. Self-interest alone moves some men.

FABLES, AESOP, SIXTH CENTURY B.C.

Mounting an insurrection, the plotters attacked and murdered the governor whom Castruccio had left behind to rule the city. Riots broke out, and the Castruccio supporters and the Poggio supporters were poised to do battle. At the height of the tension, however, Stefano di Poggio, the oldest member of the family, intervened, and made both sides lay down their arms.

A peaceful man, Stefano had not taken part in the conspiracy. He had told his family it would end in a useless bloodbath. Now he insisted he should intercede on the family’s behalf and persuade Castruccio to listen to their complaints and satisfy their demands. Stefano was the oldest and wisest member of the clan, and his family agreed to put their trust in his diplomacy rather than in their weapons.

When news of the rebellion reached Castruccio, he hurried back to Lucca. By the time he arrived, however, the fighting had ceased, through Stefano’s agency, and he was surprised by the city’s calm and peace. Stefano di Poggio had imagined that Castruccio would be grateful to him for his part in quelling the rebellion, so he paid the prince a visit. He explained how he had brought peace, then begged for Castruccio’s mercy. He said that the rebels in his family were young and impetuous, hungry for power yet inexperienced; he recalled his family’s past generosity to Castruccio. For all these reasons, he said, the great prince should pardon the Poggios and listen to their complaints. This, he said, was the only just thing to do, since the family had willingly laid down their arms and had always supported him.

Castruccio listened patiently. He seemed not the slightest bit angry or resentful. Instead, he told Stefano to rest assured that justice would prevail, and he asked him to bring his entire family to the palace to talk over their grievances and come to an agreement. As they took leave of one another, Castruccio said he thanked God for the chance he had been given to show his clemency and kindness. That evening the entire Poggio family came to the palace. Castruccio immediately had them imprisoned and a few days later all were executed, including Stefano.

Interpretation

Stefano di Poggio is the embodiment of all those who believe that the justice and nobility of their cause will prevail. Certainly appeals to justice and gratitude have occasionally succeeded in the past, but more often than not they have had dire consequences, especially in dealings with the Castruc cios of the world. Stefano knew that the prince had risen to power through treachery and ruthlessness. This was a man, after all, who had put a close and devoted friend to death. When Castruccio was told that it had been a terrible wrong to kill such an old friend, he replied that he had executed not an old friend but a new enemy.

A man like Castruccio knows only force and self-interest. When the rebellion began, to end it and place oneself at his mercy was the most dangerous possible move. Even once Stefano di Poggio had made that fatal mistake, however, he still had options: He could have offered money to Castruccio, could have made promises for the future, could have pointed out what the Poggios could still contribute to Castruccio’s power—their influence with the most influential families of Rome, for example, and the great marriage they could have brokered.

Instead Stefano brought up the past, and debts that carried no obligation. Not only is a man not obliged to be grateful, gratitude is often a terrible burden that he gladly discards. And in this case Castruccio rid himself of his obligations to the Poggios by eliminating the Poggios.

Most men are so thoroughly subjective that nothing really interests them but themselves. They always think of their own case as soon as ever any remark is made, and their whole attention is engrossed and absorbed by the merest chance reference to anything which affects them personally, be it never so remote.

ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER, 1788-1860

OBSERVANCE OF THE LAW

In 433 B.C., just before the Peloponnesian War, the island of Corcyra (later called Corfu) and the Greek city-state of Corinth stood on the brink of conflict. Both parties sent ambassadors to Athens to try to win over the Athenians to their side. The stakes were high, since whoever had Athens on his side was sure to win. And whoever won the war would certainly give the defeated side no mercy.

Corcyra spoke first. Its ambassador began by admitting that the island had never helped Athens before, and in fact had allied itself with Athens’s enemies. There were no ties of friendship or gratitude between Corcyra and Athens. Yes, the ambassador admitted, he had come to Athens now out of fear and concern for Corcyra’s safety. The only thing he could offer was an alliance of mutual interests. Corcyra had a navy only surpassed in size and strength by Athens’s own; an alliance between the two states would create a formidable force, one that could intimidate the rival state of Sparta. That, unfortunately, was all Corcyra had to offer.

The representative from Corinth then gave a brilliant, passionate speech, in sharp contrast to the dry, colorless approach of the Corcyran. He talked of everything Corinth had done for Athens in the past. He asked how it would look to Athens’s other allies if the city put an agreement with a former enemy over one with a present friend, one that had served Athens’s interest loyally: Perhaps those allies would break their agreements with Athens if they saw that their loyalty was not valued. He referred to Hellenic law, and the need to repay Corinth for all its good deeds. He finally went on to list the many services Corinth had performed for Athens, and the importance of showing gratitude to one’s friends.

After the speech, the Athenians debated the issue in an assembly. On the second round, they voted overwhelmingly to ally with Corcyra and drop Corinth.

Interpretation

History has remembered the Athenians nobly, but they were the preeminent realists of classical Greece. With them, all the rhetoric, all the emotional appeals in the world, could not match a good pragmatic argument, especially one that added to their power.

What the Corinthian ambassador did not realize was that his references to Corinth’s past generosity to Athens only irritated the Athenians, subtly asking them to feel guilty and putting them under obligation. The Athenians couldn’t care less about past favors and friendly feelings. At the same time, they knew that if their other allies thought them ungrateful for abandoning Corinth, these city-states would still be unlikely to break their ties to Athens, the preeminent power in Greece. Athens ruled its empire by force, and would simply compel any rebellious ally to return to the fold.

When people choose between talk about the past and talk about the future, a pragmatic person will always opt for the future and forget the past. As the Corcyrans realized, it is always best to speak pragmatically to a pragmatic person. And in the end, most people are in fact pragmatic—they will rarely act against their own self-interest.

It has always been a rule that the weak should be subject to the strong;

and besides, we consider that we are worthy of our power. Up till the

present moment you, too, used to think that we were; but now, after

calculating your own interest, you are beginning to talk in terms of right

and wrong. Considerations of this kind have never yet turned people aside

from the opportunities of aggrandizement offered by superior strength.

Athenian representative to Sparta,

quoted in The Peloponnesian War, Thucydides, c. 465-395 B.C.

KEYS TO POWER

In your quest for power, you will constantly find yourself in the position of asking for help from those more powerful than you. There is an art to asking for help, an art that depends on your ability to understand the person you are dealing with, and to not confuse your needs with theirs.

Most people never succeed at this, because they are completely trapped in their own wants and desires. They start from the assumption that the people they are appealing to have a selfless interest in helping them. They talk as if their needs mattered to these people—who probably couldn’t care less. Sometimes they refer to larger issues: a great cause, or grand emotions such as love and gratitude. They go for the big picture when simple, everyday realities would have much more appeal. What they do not realize is that even the most powerful person is locked inside needs of his own, and that if you make no appeal to his self-interest, he merely sees you as desperate or, at best, a waste of time.

In the sixteenth century, Portuguese missionaries tried for years to convert the people of Japan to Catholicism, while at the same time Portugal had a monopoly on trade between Japan and Europe. Although the missionaries did have some success, they never got far among the ruling elite; by the beginning of the seventeenth century, in fact, their proselytizing had completely antagonized the Japanese emperor Ieyasu. When the Dutch began to arrive in Japan in great numbers, Ieyasu was much relieved. He needed Europeans for their know-how in guns and navigation, and here at last were Europeans who cared nothing for spreading religion—the Dutch wanted only to trade. Ieyasu swiftly moved to evict the Portuguese. From then on, he would only deal with the practical-minded Dutch.

Japan and Holland were vastly different cultures, but each shared a timeless and universal concern: self-interest. Every person you deal with is like another culture, an alien land with a past that has nothing to do with yours. Yet you can bypass the differences between you and him by appealing to his self-interest. Do not be subtle: You have valuable knowledge to share, you will fill his coffers with gold, you will make him live longer and happier. This is a language that all of us speak and understand.

A key step in the process is to understand the other person’s psychology. Is he vain? Is he concerned about his reputation or his social standing? Does he have enemies you could help him vanquish? Is he simply motivated by money and power?

When the Mongols invaded China in the twelfth century, they threatened to obliterate a culture that had thrived for over two thousand years. Their leader, Genghis Khan, saw nothing in China but a country that lacked pasturing for his horses, and he decided to destroy the place, leveling all its cities, for “it would be better to exterminate the Chinese and let the grass grow.” It was not a soldier, a general, or a king who saved the Chinese from devastation, but a man named Yelu Ch‘u-Ts’ai. A foreigner himself, Ch‘u-Ts’ai had come to appreciate the superiority of Chinese culture. He managed to make himself a trusted adviser to Genghis Khan, and persuaded him that he would reap riches out of the place if, instead of destroying it, he simply taxed everyone who lived there. Khan saw the wisdom in this and did as Ch‘u-Ts’ai advised.

When Khan took the city of Kaifeng, after a long siege, and decided to massacre its inhabitants (as he had in other cities that had resisted him), Ch‘u-Ts’ai told him that the finest craftsmen and engineers in China had fled to Kaifeng, and it would be better to put them to use. Kaifeng was spared. Never before had Genghis Khan shown such mercy, but then it really wasn’t mercy that saved Kaifeng. Ch‘u-Ts’ai knew Khan well. He was a barbaric peasant who cared nothing for culture, or indeed for anything other than warfare and practical results. Ch‘u-Ts’ai chose to appeal to the only emotion that would work on such a man: greed.

Self-interest is the lever that will move people. Once you make them see how you can in some way meet their needs or advance their cause, their resistance to your requests for help will magically fall away. At each step on the way to acquiring power, you must train yourself to think your way inside the other person’s mind, to see their needs and interests, to get rid of the screen of your own feelings that obscure the truth. Master this art and there will be no limits to what you can accomplish.

Image: A Cord that

Binds. The cord of

mercy and grati

tude is threadbare,

and will break at

the first shock.

Do not throw

such a lifeline.

The cord of

mutual self-inter

est is woven of

many fibers and

cannot easily be

severed. It will serve

you well for years.

Authority: The shortest and best way to make your fortune is to let people see clearly that it is in their interests to promote yours. (Jean de La Bruyère, 1645-1696)

REVERSAL

Some people will see an appeal to their self-interest as ugly and ignoble. They actually prefer to be able to exercise charity, mercy, and justice, which are their ways of feeling superior to you: When you beg them for help, you emphasize their power and position. They are strong enough to need nothing from you except the chance to feel superior. This is the wine that intoxicates them. They are dying to fund your project, to introduce you to powerful people—provided, of course, that all this is done in public, and for a good cause (usually the more public, the better). Not everyone, then, can be approached through cynical self-interest. Some people will be put off by it, because they don’t want to seem to be motivated by such things. They need opportunities to display their good heart.

Do not be shy. Give them that opportunity. It’s not as if you are conning them by asking for help—it is really their pleasure to give, and to be seen giving. You must distinguish the differences among powerful people and figure out what makes them tick. When they ooze greed, do not appeal to their charity. When they want to look charitable and noble, do not appeal to their greed.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Why We Need to Start Seeing the Classical World in Color

Large polychrome tauroctony relief of Mithras killing a bull, originally from the mithraeum of S. Stefano Rotonodo (end of 3rd century CE), now at the Baths of Diocletian Museum, Rome (photo by Carole Raddato/Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Modern technology has revealed an irrefutable, if unpopular, truth: many of the statues, reliefs, and sarcophagi created in the ancient Western world were in fact painted. Marble was a precious material for Greco-Roman artisans, but it was considered a canvas, not the finished product for sculpture. It was carefully selected and then often painted in gold, red, green, black, white, and brown, among other colors.

A number of fantastic museum shows throughout Europe and the US in recent years have addressed the issue of ancient polychromy. The Gods in Color exhibit travelled the world between 2003–15, after its initial display at the Glyptothek in Munich. (Many of the photos in this essay come from that exhibit, including the famed Caligula bust and the Alexander Sarcophagus.) Digital humanists and archaeologists have played a large part in making those shows possible. In particular, the archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann, whose research informed Gods in Color, has done important work, applying various technologies and ultraviolet light to antique statues in order to analyze the minute vestiges of paint on them and then recreate polychrome versions.

The Archer from the western pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aigina, reconstruction, color variant A from the Gods of Color exhibit (photo by Marsyas/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Acceptance of polychromy by the public is another matter. A friend peering up at early-20th-century polychrome terra cottas of mythological figures at the Philadelphia Museum of Art once remarked to me: “There is no way the Greeks were that gauche.” How did color become gauche? Where does this aesthetic disgust come from? To many, the pristine whiteness of marble statues is the expectation and thus the classical ideal. But the equation of white marble with beauty is not an inherent truth of the universe. Where this standard came from and how it continues to influence white supremacist ideas today are often ignored.

Most museums and art history textbooks contain a predominantly neon white display of skin tone when it comes to classical statues and sarcophagi. This has an impact on the way we view the antique world. The assemblage of neon whiteness serves to create a false idea of homogeneity — everyone was very white! — across the Mediterranean region. The Romans, in fact, did not define people as “white”; where, then, did this notion of race come from?

A painted Romano-Egyptian mummy mask of a man (late 2nd century CE), plaster, paint, glass, now at the Rhode Island School of Design (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

In early modern Europe, taxonomies were all the rage. What would later be termed the “scientific revolution” was marked by a desire to categorize, label, and rank everything from plants to minerals. It was only a matter of time before humans were similarly subjected to such manmade systems of classification. At the same time, artists began to engage with mathematics and anatomy and to use classical sculpture as a means of addressing the question of replicable beauty through proportions.

One of the most influential art historians of the era was Johann Joachim Winckelmann. He produced two volumes recounting the history of ancient art, Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (1764), which were widely read and came to form a foundation for the modern field of art history. These books celebrate the whiteness of classical statuary and cast the Apollo of the Belvedere — a Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic bronze original — as the quintessence of beauty. Historian Nell Irvin Painter writes in her book The History of White People (2010) that Winckelmann was a Eurocentrist who depreciated people of other nationalities, like the Chinese or the Kalmyk.

The Apollo Belvedere, now at the Vatican Museums, was viewed in the 18th century as the model of beauty. Artists became fascinated with the statue after its discovery in the late 15th century, including Albrecht Dürer. (photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia)

“Color in sculpture came to mean barbarism, for they assumed that the lofty ancient Greeks were too sophisticated to color their art,” Painter writes. The ties between barbarism and color, civility and whiteness would endure. Not to mention Winckelmann’s pronounced preference for sculptures of gleaming white men over women. Regardless of his own sexual identity — which may have been expressed in this preference — Winckelmann’s gender bias would go on to have an impact on white male supremacists who saw themselves as upholding an ideal.

Winckelmann wasn’t the only man obsessed with the Apollo Belvedere. The Dutch anatomist Pieter Camper believed that he could find the formula for perfect beauty through facial angles and used the statue as a standard to be attained. He began to measure human and animal facial features, particularly the lines running from the nose to the ear and the forehead to the jawbone. Those ratios were later used by others to create the racist “cephalic index,” which categorized humans based on the width and length of their facial features. The Nazis drew on the index to support notions of Aryan superiority in Germany during the Third Reich.

Page from Pieter Camper, The Works of the late Professor Camper, on The Connexion [sic] between the Science of Anatomy and The Arts of Drawing, Painting, Statuary &c. &c. (London: Charles Dilly, 1794) (image via the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Camper’s successors perpetuated and reshaped many of his ideas to be even more biased towards newly constructed races. As classicist Christopher B. Krebs wrote in A Most Dangerous Book, his work on the Third Reich’s manipulation of the classical author Tacitus, “Throughout the nineteenth century, scientists would scour far and wide mismeasuring human anatomy. The more data that was compiled, the less significant the result became. Where science failed, prejudice stepped in and observation yielded to opinion.” This prejudice was seen particularly in the diagramming of beauty within anatomical textbooks of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The son of a famous botanist, Mathias Marie Duval developed numerous anatomical models that were broadly used in medical schools and perpetuated ideas of whiteness that never existed in the ancient world. They were derived from examples of classical sculpture, particularly (you guessed it) the Apollo Belvedere.

Duval’s diagram of the facial angle of an antique head, based on Camper’s work with the Apollo Belvedere; fig. 63 in Matthias Duval’s Artistic Anatomy: Completely Revised, with Additional Original Illustrations. Edited and Amplified by A. Melville Paterson, M.D. (1919) (screenshot via Internet Archive)

Too often today, we fail to acknowledge and confront the incredible amount of racism that has shaped the ideas of scholars we cite in the field of ancient history. For example, I recently, came across Tenney Frank’s disturbing article “Race Mixture in the Roman Empire” while looking through an edited volume. First published in The American Historical Review in July 1916, the article sees Frank attempting to count extant inscriptions (mostly epitaphs) in order to gauge whether “race mixing” contributed to the decline of the Roman empire. It was then reprinted without comment in Greek historian Donald Kagan’s 1962 collection of articles on the fall of Rome.

I am not suggesting that Kagan is a racist (far from it), but, at the least, he should have contextualized Frank’s essay in his introduction to the volume and highlighted it as an example of the virulent racism built into the foundation of the Classics field. As Denise Eileen McCoskey points out in her excellent book Race: Antiquity and Its Legacy, Frank’s argument is not only untrue, it is dangerous. It provides further ammunition for white supremacists today, including groups like Identity Europa, who use classical statuary as a symbol of white male superiority. It also continues to buttress the false construction of Western civilization as white by politicians like Steve King.

Seattle has never looked better. #FashTheCity http://pic.twitter.com/UA3DjDKKnq

— IDENTITY EVROPA (@IdentityEvropa) November 4, 2016

How can we address the problem of the lily white antiquity that persists in the public imagination? What can classicists learn from the debate over whiteness and ancient sculpture?

First, we must consider why we are such a homogenous field. According to the Society for Classical Studies, the leading association for Classics in the United States, in 2014, just 9% of all undergraduate Classics majors were minorities. This number decreases the higher into academia you go. Just 2% of tenured full-time Classics faculty were minorities, according to the study.

Do we make it easy for people of color who want to study the ancient world? Do they see themselves in the ancient landscape that we present to them? The dearth of people of color in modern media depicting the ancient world is a pivotal issue here. Movies and video games, in particular, perpetuate the notion that the classical world was white. This is an issue when 70% of my students tell me that games such as Ryse: Son of Rome (which uses white statues to decorate the city of Rome and white Roman soldiers as lead characters), as well as films like Gladiator (which has a man from New Zealand playing the Spaniard Maximus) and the 300 (which has xenophobic depictions of Persians) led them to take my courses.

youtube

If we want to see more diversity in Classics, we have to work harder as public historians to change the narrative — by talking to filmmakers, writing mainstream articles, annotating our academic writing and making it open access, and doing more outreach that emphasizes the vast palette of skin tones in the ancient Mediterranean. I’m not suggesting that we go, with a bucket in hand, and attempt to repaint every white marble statue across the country. However, I believe that tactics such as better museum signage, the presentation of 3D reconstructions alongside originals, and the use of computerized light projections can help produce a contextual framework for understanding classical sculpture as it truly was. It may have taken just one classical statue to influence the false construction of race, but it will take many of us to tear it down. We have the power to return color to the ancient world, but it has to start with us.

Painted terra cotta cinerary urn (150–100 BCE), originally from Chiusi, now at the British Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Detail of painted terra cotta cinerary urn (150–100 BCE), originally from Chiusi, now at the British Museum (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

The post Why We Need to Start Seeing the Classical World in Color appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2r22wfq

via IFTTT

0 notes