#like at least in Truffaut's writings (which i also have opinions about but i can follow his reasoning a lot more & generally agree with him

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Pauline Kael, circles & squares

#slay queen <3#articles#sorry she's so funny. she's so not here for whatever sarris is selling & frankly neither am i girl what ARE you on about#like ok i def do not care for auteur theory to begin with BUT sarris's 'notes on' in particular#is like. one of those things that would NOT have been published if it were written by a woman#(actually i say that but i def dont know enough about 1960s film criticism to say that w my chest)#(bc the 60s & also art criticism is notoriously woo)#(however)#(what For Real are you talking about. in my notes on his article i said: auteur theory allows you to be pedantically observant about#a director's entire oeuvre without adding anything of value. like ok now extrapolate?)#but also sarris specifically is SOOO clued into the cult of personality#like at least in Truffaut's writings (which i also have opinions about but i can follow his reasoning a lot more & generally agree with him#but at least with him the final product is still the starting point#whereas sarris FOR REAL is like. 'its about the auteur's personality irl & how it relates to the movies' girl do you Know these directors?#personally? have yo ubeen in their houses? at their dinner tables (AS A FRIEND NOT AS A CRITIC GUEST)#how do you know what their personalities are?#& i am aware im just regurgitating very basic criticisms on the auteur theory but like whatever. still true.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Question of Auters: A Director’s Influence

John Ford. Alfred Hitchcock. Stanley Kubrick. Martin Scorsese. Orson Welles. Charlie Chaplin. Tim Burton. David Lynch. Francis Ford Coppola. Steven Spielberg.

If you have only the barest knowledge of film, you recognize at least one of these names, and well you should. These are the names upon which an entire school of thought is built, the greatest directors in film history. These are the directors that matter, the creators that shaped an industry. These are the men who made important films.

Or at least, so popular auteur theory would have us believe.

Auteur is a word heard often within the film community, thrown around as a casual term, part of the jargon used by those interested and well-versed in cinema. Even those who aren’t interested or well-versed might recognize the word from use alone, and either way, depending on your viewpoint, it may inspire either a wise, respectful nod, or a disgusted snort.

Before we jump into the reasons for those reactions, however, perhaps we should discuss what, exactly, an auteur is.

The word auteur is a French noun, defined by dictionary.com like this:

A filmmaker whose individual style and complete control over all elements of production give a film its personal and unique stamp.

Or, for a simpler definition, just translate the word literally: auteur is French for author.

It’s a reasonable translation, one that makes a lot of sense. In many ways, despite not literally writing the story or script, a director is the person the most responsible for a film’s end result. They get the final call. They work with the actors. It is they who have the ‘vision’ of the film, the end product in mind throughout the entire project.

It’s no surprise that in a world fascinated by the relatively new (and relatively fast growing) medium of film, it didn’t take long for the public to become equally fascinated by the people most obviously behind the movie-making process: the directors.

The term auteur theory is not a new one. It was discussed first by future author François Truffaut, in Cahiers du Cinéma titled Une certaine tendance du cinéma français, which, translated, is: “A Certain Tendency of French Cinema”, in which Truffaut criticized French cinema, championing instead American directors, notably Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks. It was also Truffaut who said:

“There are no good or bad films. Only good or bad directors.”

Later, the term auteur theory was first coined by American critic Andrew Sarris in a 1962 essay entitled Notes on the Auteur Theory, followed by a book called The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929–1968, which would go on to influence movie critics, raising further awareness of the idea of auteur theory in the first place.

But what is an auteur? We’ve named a few, sure, and we’ve even discussed the basic definition, but how can you tell if a film is created by an auteur, rather than ‘just’ a director? Where does the difference come in?

The answer lies in the examples used by Truffaut in his essay: Howard Hawks, and Alfred Hitchcock.

Both of those directors help set the gold standard for what would be considered the criteria for the auteur style, very simply by having a style of their own.

See, put very simply, Hitchcock and Hawks, while creating very different films, had one thing in common in terms of directing: they both had very distinct individual styles.

In Sarris’s 1962 essay, he laid down the groundwork, three major rules, that all directors must follow to be considered an auteur, all three of which Hawks and Hitchcock embodied to a T:

“A great director has to at least be a good director.”

In other words, to be an auteur, the director in question has to be at least a competent story-teller and film-maker. They must have some level of ability in terms of technicals.

2. “Over a group of films a director must exhibit certain recurrent characteristics of style which serve as his signature.”

An auteur must have a signature style. This is probably the rule that people are the most familiar with, the distinguishable personality that makes Tim Burton’s films dark and full of stripes, or why Hitchcock has an ‘icy blonde’ in nearly every one of his best films. This is the element that dictates that, for it to be the work of a true auteur, you can tell who the director was, just by looking at the film itself.

3. “Interior meaning is extrapolated from the tension between a directors personality and his material.”

In simpler terms, auteur films have to reveal the director’s innermost thoughts and ideas about life, the human condition, films, anything, really. It’s these elements that give us Steven Spielberg’s use of fathers (and lack thereof) in his films, or his themes of ‘Growing Up Sucks’ and Tear Jerker stories of idealism, or Howard Hawks’ themes of manhood, or Martin Scorsese’s stories of Anti-Heroes, cynicism, and the idea of Family vs. Career.

To quote Andre Brazin:

“The politique des auteurs consists, in short, of choosing the personal factor in artistic creation as a standard of reference, and then assuming that it continues and even progresses from one film to the next. It is recognized that there do exist certain important films of quality that escape this test, but these will systematically be considered inferior to those in which the personal stamp of the auteur, however run-of-the-mill the scenario, can be perceived even minutely.”

In other words? Being a bad film produced with a recognizable style is better than being a good film with a bland style.

The question is…is that true?

Is it better to be a worse film with the distinct fingerprints of a well-known name, or a good film with no individualism as a style?

And an even bigger question: does it all truly lie in the hands of the director?

Here’s the thing:

While auteur theory existed in the 1950s and 1960s, it wasn’t really considered a big deal, especially by the auteur’s themselves. Hawks and Hitchcock thought of themselves as just working in a trade, not making art. It was in the following decade that the idea truly took off.

The ‘auteurs’ emerged, en masse, in the 1970s, and with good reason: the entire idea of auteur is impossible without the existence of film school, and the ability and reason to watch a director’s entire filmography. The distinct styles of Orson Welles, Charlie Chaplin, and Alfred Hitchcock directly influenced the ‘movie brat’ director generation, such as Scorsese, Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola, and Woody Allen, directors who had not only grown up with films, but with film studies. This led to the birth of ‘New Hollywood’, the age of the director, a period that returned the state of productions to the way it had been in lulls of studio involvement in the past. It’s no coincidence that many films on ‘best of’ lists are created by auteurs from the 1970s (although I should point out that there are no shortage of films created by stylistic directors beforehand). Although the idea of ‘auteur’ had been around for decades, an argument could be made that director worship truly took off in the 1970s with films like The Godfather, Taxi Driver, Jaws, and Annie Hall.

The success of these films encouraged studios to put more projects in the hands of these up-and-coming directors, fresh and eager to tell new stories and make more films. As big as the idea became in the 1950s and 1960s, it can be very easily argued that the idea experienced a rebirth in the 1970s, shaping very much the idea and examples we have available to us now. But just as it sparked a resurgence, it also sparked a backlash, a backlash that some would argue was very much needed.

Some, like critic Pauline Kael, have been very outspoken against auteur theory, with plenty of arguments being made against it, such as it’s tendency to elevate lesser films, claiming that a bad movie by a great director is important simply because it has his style. Other criticisms point out that just because a director forces his style on a film doesn’t necessarily mean it fits the individual film, making each movie more about style than substance (a common criticism of Stanley Kubrick’s work). Other complaints explain that the idea of ‘auteur’ excuses Prima Donna Director behavior, or encourages overblown expressions of ‘vision’ that end in disasters.

These are valid criticisms.

But there is one that is held above the rest, one final critique that remains, in my opinion, the nail in the coffin against auteur theory being considered so incredibly great, is that: film is, by nature, a collaborative effort.

I asked earlier if this all lies in the hands of the direction, and the fact is, no, it doesn’t.

There’s no Tim Burton or Steven Spielberg style without their signature Production Posses. Alfred Hitchcock’s iconic work doesn’t rest on his shoulders alone. Every director, no matter how involved or talented, relies on a network of people, all bearing a substantial portion of the weight of an individual film. The best directors know this.

The fact is, no matter how talented the director is, there must be a limit to the director’s power, or a film’s production can turn into an egotistical disaster. By nature, movie productions are group efforts. Between actors, producers, editors, cameramen, costume designers, transportation, catering, and countless other individuals with vital jobs, films are massive efforts from massive amounts of people. Every movie, no matter how many ‘hats’ the director wore, is the result of the coordination of several people executing a vision that, in the end, may have been the director’s, but by no means was exclusively his.

“Boiling it down to one person and placing their influence above everyone else makes for bad movies.” (“The Ultimate Guide to the Best Auteur Directors.” StudioBinder, 12 Feb. 2020, www.studiobinder.com/blog/auteur-theory/.)

In a nutshell?

Are directors important?

Of course they are. They are still the head of a production, and they still do (often) have identifiable fingerprints on each film they’re a part of.

But with that said, it’s vital to remember that directors are not the end-all and be-all of an individual film. Auteur theory is a valid element of film study, and by no means should it be omitted, but it should be contextualized in film history, a reminder that no director stands alone.

And the best directors, the auteurs themselves, would agree.

Thank you so much for reading, and I’ll see you in the next article.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Oh wise vintagegeekculture, might I ask your opinion on Michael Moorcock's essay "Epic Pooh"?

I am American as all-get-out. Stranger Things is practically a documentary about my rural childhood;there were a million little sense memory triggers in that series for me. Sothere is probably a cultural context to that very very English essay thatdiscusses a very very English relationship to lulling sentimentality and class and the countryside that I willfully concede that I am simply not grasping. The English seem tothink entirely in terms of debating sentimental imagery: “Mother London” vs.the “Ploughman’s Lunch” and “Little Britain.” Althought it is a serious issue,listening to British debates on Brexit often felt like hearing to the “Darmokand Jalad at Tanagra” aliens from TNG having a loud argument about who’s Momloves them more.

But…from my perspectiveas an outsider and foreigner, I think the general point Moorcock makes iscorrect: Fantasy was created by men like Tolkien and Lord Dunsany who wereviolently hostile to the modern world and so their work very studiously avoidedtalking about the modern world except in opposition to it (for instance, theonly person to push industrialization and scouring the countryside is anasshole wizard; the only person who talks like T.S. Elliot’s Londoners is the despicableSméagol). Lord Dunsany was a great writer, but seems like a thin-bloodedaristocrat, like a Brit Ashley Wilkes from GoneWith the Wind, who even in the 1970s, wrotehis stories with a quill pen and wore an ascot tie to book readings.

Moorcock is right whenhe says that fantasy often avoids reflecting the world around us, and thatbeing overly sentimental about the past serves the interest of reactionaries(note that he did not call Tolkien and Dunsany and the rest reactionaries…atleast in a way that was visible in their work – he did say that about Adams andLewis though). The most important quote in that essay is “Ideally fiction should offer us escape and force us, at least, to askquestions; it should provide a release from anxiety but give us some insightinto the causes of anxiety.” I mean, fantasy as a genre was so detachedfrom “real world” issues that when someone like Tad Williams started to includesomething as fundamental as economics into his fantasy worlds starting in the1980s, people treated him like a total genius (Which Tad Williams IS,incidentally - these days, people only really know Tad Williams, if they knowhim at all, as the inspiration for George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones).

One of the great themesof Moorcock’s work is the way that authoritarians use sentimental imagery ofthe past to manipulate people. If you read Epic Pooh, also read his other book,“The Dreamthief’s Daughter,” the opening third to half is set in Nazi Germany.It’s actually more helpful to understand the point of this essay to read “Dreamthief’sDaughter,” since, in the words of Francois Truffaut, “the only way to critiquea movie properly is to make another movie.” Dreamthief’s Daughter starts with a“Good German,” von Bek, who is horrified that his Germany was taken over byNazism, how they replace “self respect with a kind of strutting self-esteem.”At one point, our hero has to hide in the German countryside, and he mentionshow sinister the small storybook German towns he passes through seem, romanticized by fascists after Hitlercame to power, as they were pushed front and center as the “true Germany.”

Of all the books everwritten about the Nazis and arch-reactionaries, Moorcock gets it the most rightin “Dreamthief’s Daughter.” They were boring failsons, not supervillains.Rudolf Hess was described as the most irritating person to sit next to on thebus to a con and who believed magic and ghosts were real; von Bek said that “inmy many adventures, I showed true courage only once: in not throwing RudolfHess out of my car.” Von Bek’s comments on Hitler himself: “An evening withHitler was like an evening with an extremely boring maiden aunt.” He was alsothe first person I can think of to point out how reactionary fascists oftenhave really bad taste, too: drawing imagery from bad comic operas and Americanmovies about Rome. That last bit should be all too familiar to people whonotice how many American reactionaries love the hell out of the movie 300 (amovie I really like too, incidentally, but it’s okay to enjoy something if you understand it).

Also, “Dreamthief’sDaughter” had a great finale: imagine a flight of dragons coming out to fight theBattle of Britain.

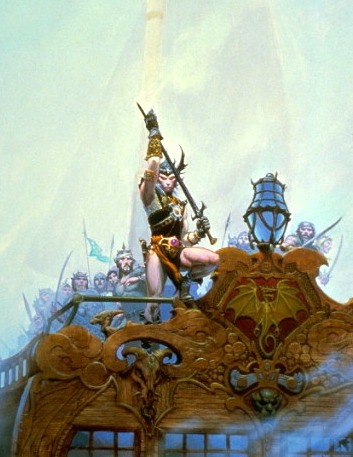

The point, that fantasycan be infantilizing, is a good point, but Moorcock is the weirdestpossible person on the face of the earth to make it. Moorcock got famous bywriting about brooding angsty albinos who cry all the time for the benefit ofteenage heavy metal fans and dungeon masters in Reeboks. I love his stuff but that’s who he is,that’s the stuff that pays his mortgage, that’s his audience. His stuff is good but it reminds me ofthose White Wolf games in the 1990s that look silly and dated in retrospectbecause they trowel on the angst and transgression and put on airs (White Wolf,incidentally, was named after Moorcock’s greatest hero, Elric the White Wolf…andin the 1990s, White Wolf’s publishing arm dedicated itself to reprinting someof Moorcock’s less widely seen novels, a service for which I thank them verymuch). I am actually legitimately surprised that Moorcock never wrote a “sad sexy vampire” novel. God, can you imagine the kind of satire that the anarchic MAD magazine of the 50s would do of the Elric stuff? Elric screaming his soul is black at the breakfast table, while threatening to kill himself over a hangnail.

236 notes

·

View notes