#like I still remain unconvinced that Vane's weirdly tooled leather pants are even slightly historical. and they're still generic as hell lo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ooh, a great addition!! I'm not as well up on C16th fashion, so thank you for the context.

Turns out I was partly wrong! Leather jerkins were worn in the 15th and 16th centuries, and buff leather coats were a large part of C16th military armour, though they were often a padding layer under metal. And we DO have extant examples and references to leather hose/breeches/trousers. Huzzah! Precedent!

However, I do think my point stands. Because yes, leather did exist as a garment material - but extremely not how modern designers seem to think.

Compare, for example, The Tudors' Henry VIII or Will's Marlowe above, with actual leather English Renaissance jerkins:

(Worth noting that the left-hand example is described as dark brown, though it's aged into a blacker colour.)

Or The Musketeers with actual C17th buff leather army coats (or, god forbid, actual C17th Mousquetaires du roi):

There's even this leather waistcoat from c. 1714-26, smack bang in the Golden Age of Piracy:

And here are some breeches/trousers I could find, from the late 18th/early 19th centuries:

And, as linked by mstyr, we know that Baron John Petre bought some chamois leather hose from Richard Smithick on Fleet Street in 1577, with lace, silk, and razed/slitted cannions (the narrow part that reached down to the knee). I also found leather jerkins mentioned in that period in the royal wardrobe warrant, including perfumed, or imported Spanish, leather.

Of course, these are all quite fashionable garments, though we should remember that evidence is biased towards the rich. We can probably safely assume the existence of plainer, working people's leather jerkins and trousers/breeches/hose, as well as utilitarian garments like chaps and aprons, for which we don't have a record.

Still: none of these examples look remotely like the ones in modern media, particularly not the generic Vikings/Black Sails/The Tudors look I criticised. If Shakespeare in Love was going for an accurate leather look, they could have given William a brown, cream, or yellow jerkin over a long-sleeved fabric doublet, with some modest (considering his lower status) pinking or slashing. The Musketeers could have given their men high-waisted, yellow or tan buff coats, with big shirts and bright sashes. Arguably, Robin Hood's highly tooled brown leather jerkin has something going for it, but it definitely leans more toward fantasy armour than middle ages fashion, and what they've put Guy in rather undermines the historicism!

It's fairly clear that these modern designs don't come from any attention to extant historical garments or records. And it seems to me that what evidence we do have of historical leather garments doesn't speak to them being particularly common, outweighed as they are by images and examples of wool, linen, silk, and cotton. Leather armour had a brief heyday in the C17th buff coat, but that looked nothing like the leather armour we see in fantasy/period media.

To be clear, my problem with this genre of period costume design isn't just the fact of leather pants. It's generic in plenty of other ways: limited, muted colour palette, often further dulled with dirt (as if people in history didn't have access to cheap, natural dyes, didn't like bright things or fashion, and didn't know how to stay clean); rough, "handmade-look" stitching (as if Vikings, pirates, or English folk heroes didn't have access to highly skilled tailors, leatherworkers, and armourers, or as if, before industrialisation and fast fashion, almost everyone either had, or knew someone with, the skill to neatly make and mend clothing); impractical or anachronistic flourishes (wide, multi-buckled belts; everyday bracers; studs and plates haphazardly attached to anything and everything); high boots on everyone (because no one serious or interesting would wear stockings!); and catering to modern beauty standards with spandex pants, low-cut shirts, and modern hair and makeup (because actors must look as sexy as possible, and audiences can't understand that fashion and beauty standards change over time).

Which is why what Flag does right is not eschew leather entirely, but utilise it with creativity and intention, with context, intertext, and subtext, to create meaning and convey character in complex and nuanced ways.

Still. It is nice to set the record straight on actually historical leather <3

So I accidentally almost got into an argument on Twitter, and now I'm thinking about bad historical costuming tropes. Specifically, Action Hero Leather Pants.

See, I was light-heartedly pointing out the inaccuracies of the costumes in Black Sails, and someone came out of the woodwork to defend the show. The misunderstanding was that they thought I was dismissing the show just for its costumes, which I wasn't - I was simply pointing out that it can't entirely care about material history (meaning specifically physical objects/culture) if it treats its clothes like that.

But this person was slightly offended on behalf of their show - especially, quote, "And from a fan of OFMD, no less!" Which got me thinking - it's true! I can abide a lot more historical costuming inaccuracy from Our Flag than I can Black Sails or Vikings. And I don't think it's just because one has my blorbos in it. But really, when it comes down to it...

What is the difference between this and this?

Here's the thing. Leather pants in period dramas isn't new. You've got your Vikings, Tudors, Outlander, Pirates of the Caribbean, Once Upon a Time, Will, The Musketeers, even Shakespeare in Love - they love to shove people in leather and call it a day. But where does this come from?

Obviously we have the modern connotations. Modern leather clothes developed in a few subcultures: cowboys drew on Native American clothing. (Allegedly. This is a little beyond my purview, I haven't seen any solid evidence, and it sounds like the kind of fact that people repeat a lot but is based on an assumption. I wouldn't know, though.) Leather was used in some WWI and II uniforms.

But the big boom came in the mid-C20th in motorcycle, punk/goth, and gay subcultures, all intertwined with each other and the above. Motorcyclists wear leather as practical protective gear, and it gets picked up by rock and punk artists as a symbol of counterculture, and transferred to movie designs. It gets wrapped up in gay and kink communities, with even more countercultural and taboo meanings. By the late C20th, leather has entered mainstream fashion, but it still carries those references to goths, punks, BDSM, and motorbike gangs, to James Dean, Marlon Brando, and Mick Jagger. This is whence we get our Spikes and Dave Listers in 1980s/90s media, bad boys and working-class punks.

And some of the above "historical" design choices clearly build on these meanings. William Shakespeare is dressed in a black leather doublet to evoke the swaggering bad boy artist heartthrob, probably down on his luck. So is Kit Marlowe.

But the associations get a little fuzzier after that. Hook, with his eyeliner and jewellery, sure. King Henry, yeah, I see it. It's hideously ahistorical, but sure. But what about Jamie and Will and Ragnar, in their browns and shabby, battle-ready chic? Well, here we get the other strain of Bad Period Drama Leather.

See, designers like to point to history, but it's just not true. Leather armour, especially in the western/European world, is very, very rare, and not just because it decays faster than metal. (Yes, even in ancient Greece/Rome, despite many articles claiming that as the start of the leather armour trend!) It simply wasn't used a lot, because it's frankly useless at defending the body compared to metal. Leather was used as a backing for some splint armour pieces, and for belts, sheathes, and buckles, but it simply wasn't worn like the costumes above. It's heavy, uncomfortable, and hard to repair - it's simply not practical for a garment when you have perfectly comfortable, insulating, and widely available linen, wool, and cotton!

As far as I can see, the real influence on leather in period dramas is fantasy. Fantasy media has proliferated the idea of leather armour as the lightweight choice for rangers, elves, and rogues, a natural, quiet, flexible material, less flashy or restrictive than metal. And it is cheaper for a costume department to make, and easier for an actor to wear on set. It's in Dungeons and Dragons and Lord of the Rings, King Arthur, Runescape, and World of Warcraft.

And I think this is how we get to characters like Ragnar and Vane. This idea of leather as practical gear and light armour, it's fantasy, but it has this lineage, behind which sits cowboy chaps and bomber/flight jackets. It's usually brown compared to the punk bad boy's black, less shiny, and more often piecemeal or decorated. In fact, there's a great distinction between the two Period Leather Modes within the same piece of media: Robin Hood (2006)! Compare the brooding, fascist-coded villain Guy of Gisborne with the shabby, bow-wielding, forest-dwelling Robin:

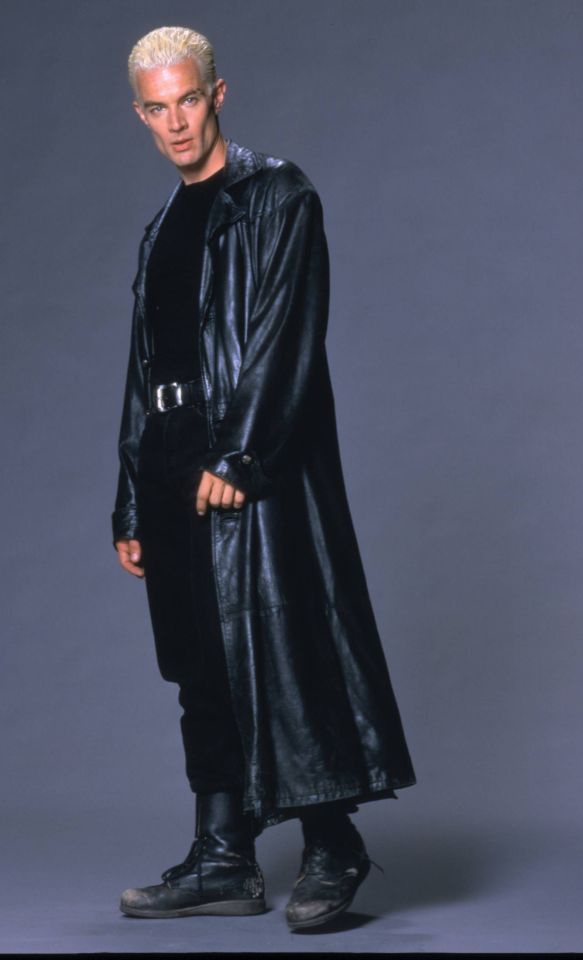

So, back to the original question: What's the difference between Charles Vane in Black Sails, and Edward Teach in Our Flag Means Death?

Simply put, it's intention. There is nothing intentional about Vane's leather in Black Sails. It's not the only leather in the show, and it only says what all shabby period leather says, relying on the same tropes as fantasy armour: he's a bad boy and a fighter in workaday leather, poor, flexible, and practical. None of these connotations are based in reality or history, and they've been done countless times before. It's boring design, neither historically accurate nor particularly creative, but much the same as all the other shabby chic fighters on our screens. He has a broad lineage in Lord of the Rings and Pirates of the Caribbean and such, but that's it.

In Our Flag, however, the lineage is much, much more intentional. Ed is a direct homage to Mad Max, the costuming in which is both practical (Max is an ex-cop and road warrior), and draws on punk and kink designs to evoke a counterculture gone mad to the point of social breakdown, exploiting the thrill of the taboo to frighten and titillate the audience.

In particular, Ed is styled after Max in the second movie, having lost his family, been badly injured, and watched the world turn into an apocalypse. He's a broken man, withdrawn, violent, and deliberately cutting himself off from others to avoid getting hurt again. The plot of Mad Max 2 is him learning to open up and help others, making himself vulnerable to more loss, but more human in the process.

This ties directly into the themes of Our Flag - it's a deliberate intertext. Ed's emotional journey is also one from isolation and pain to vulnerability, community, and love. Mad Max (intentionally and unintentionally) explores themes of masculinity, violence, and power, while Max has become simplified in the popular imagination as a stoic, badass action hero rather than the more complex character he is, struggling with loss and humanity. Similarly, Our Flag explores masculinity, both textually (Stede is trying to build a less abusive pirate culture) and metatextually (the show champions complex, banal, and tender masculinities, especially when we're used to only seeing pirates in either gritty action movies or childish comedies).

Our Flag also draws on the specific countercultures of motorcycles, rockers, and gay/BDSM culture in its design and themes. Naturally, in such a queer show, one can't help but make the connection between leather pirates and leather daddies, and the design certainly nods at this, with its vests and studs. I always think about this guy, with his flat cap so reminiscient of gay leather fashions.

More overtly, though, Blackbeard and his crew are styled as both violent gangsters and countercultural rockstars. They rove the seas like a bikie gang, free and violent, and are seen as icons, bad boys and celebrities. Other pirates revere Blackbeard and wish they could be on his crew, while civilians are awed by his reputation, desperate for juicy, gory details.

This isn't all of why I like the costuming in Our Flag Means Death (especially season 1). Stede's outfits are by no means accurate, but they're a lot more accurate than most pirate media, and they're bright and colourful, with accurate and delightful silks, lace, velvets, and brocades, and lovely, puffy skirts on his jackets. Many of the Revenge crew wear recognisable sailor's trousers, and practical but bright, varied gear that easily conveys personality and flair. There is a surprising dedication to little details, like changing Ed's trousers to fall-fronts for a historical feel, Izzy's puffy sleeves, the handmade fringe on Lucius's red jacket, or the increasing absurdity of navy uniform cuffs between Nigel and Chauncey.

A really big one is the fact that they don't shy away from historical footwear! In almost every example above, we see the period drama's obsession with putting men in skinny jeans and bucket-top boots, but not only does Stede wear his little red-heeled shoes with stockings, but most of his crew, and the ordinary people of Barbados, wear low boots or pumps, and even rough, masculine characters like Pete wear knee breeches and bright colours. It's inaccurate, but at least it's a new kind of inaccuracy, that builds much more on actual historical fashions, and eschews the shortcuts of other, grittier period dramas in favour of colour and personality.

But also. At least it fucking says something with its leather.

#Togas does meta#fashion history#thank you for making me lose an entire evening to researching and writing this (genuine) (it was so much fun)#wouldn't have got there without the starting point you gave me!#like I still remain unconvinced that Vane's weirdly tooled leather pants are even slightly historical. and they're still generic as hell lo#sidenote: sources for all those extant garments are in the alt text#I find the buff waistcoat particularly fascinating - I've looked at a fair few waistcoats from that era and never seen one like it!#which like - yeah I still get the impression that leather garments weren't exactly COMMON until the C20th#with the exception of specific occupational garb like chaps/aprons (and obvs like shoes and gloves and stuff)#and very specific subcultures - iirc the C17th buccaneers are said to have worn pretty rough leather from their work#like yeah the point isn't that 'there are no leather garments in the historical record'#more that a) they're not as common as in period costuming; and b) those designs are still generic; so c) OFMD is still inventive/interestin#BUT. you are still right that my original statements were a bit too sweepingly dismissive#and if you have any other good sources or extant examples please let me know!! <3

1K notes

·

View notes