#lets start the book again but i take a shot for every thematic inconsistency and pass out before Jonathan even meets the count

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Shitty Luca Movie Recap, Episode 4

Can’t Watch Nina, Even For Luca?

Don’t Worry, Me Neither. Goodbye.

.

..

...

Ok, fine, I’ll talk about the damn thing.

So it’s a warm September night, and I’m in the mood for a Luca Marinelli feature. In my infinite wisdom I choose Nina. “It’s directed by a woman,” I reason, “and women know what’s up.” ‘What’s up’ in this particular case is code for ‘how to frame beautiful men for the female gaze’. Because women can be auteurs, too, and being an auteur means making movies about your own personal wank material.

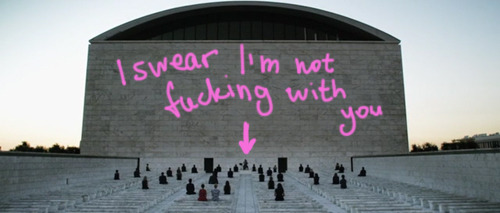

Turns out, sometimes a woman’s wank material consists less of a gorgeous male form and more of fascist architecture. We’ll discuss the former in due time, but for now, what’s Nina even about? Well, at its core it’s a simple story about a young woman who doesn’t know what she wants, set against the backdrop of the Rome that is almost entirely empty due to most people leaving for the summer. This could have been a fairly straightforward coming-of-age film, but Nina is too indie and up its own ass for that. Literally nothing of note happens in this movie, and it’s all long static wide shots of empty streets, endless stairs, and domineering largeness of Rome’s most famous fascist buildings such as the Palace of Italian Civilization, the Sapienza University of Rome, Palazzo dei Congressi, and, most prominently, the Fountains Hall. (Google what they look like if you don’t know.) Now, I’m guessing those locations weren’t chosen by accident. They could have easily added to the creepiness of the movie — and I’m assuming creepiness was intended; otherwise how do you explain these hoverboarding nuns?

Anyway, the employment of the locations could have been atmospheric and thematic had the shots not been so bland. But they are. Bland, flat, and always looking the same no matter what is happening in the scene. Usually audiences are willing to sit through slow uneventful movies because of interesting visuals or characters worthy of attention, but Nina has neither. The titular character herself is tedious. Even her bad fashion sense is bad in a boring way that doesn’t tell you anything about her. Is she stuck in perpetual adolescence? Is she searching to get in touch with her sensuality? Who knows. The only thing I’m certain of is that she needs to learn to tuck her tops into her bottoms.

Nina spends her days giving singing lessons, going to Chinese calligraphy classes, eating cake, exercising and taking midnight walks in the empty city. She wants to go to China in September — it’s the closest thing to a goal she has — yet she’s done no preparations, and instead of learning Mandarin she’s studying calligraphy. And she’s real bad at it, too.

There are reoccurring visual elements in the movie besides the vast emptiness: stairs, white columns, a jogger, a red dress, animals… You’d think those were very straightforward symbols, but they’re used too sporadically and inconsistently to hold any meaning. For example, animals. Nina is tasked with both helping out in a pet store and house-sitting an apartment with a German shepherd (a good boy named Homer), a guinea pig and a tank full of fish. The instructions she’s given are absurd, like feeding the dog sleeping pills and putting the guinea pig on a diet. And then there’s a supposedly American TV show always playing in and out of diegesis about dogs living in cages and swimming happily in pools, and it looks and sounds like a video off the political section on the dog version of YouTube. It contains timeless classics like “You are a dog born in the age of consumerism” and “Depression is an evil illness now spreading amongst dogs of every breed, dogs belonging to every social class.” The butter commercial from Crazy Ex-Girlfriend could never. And I wish the whole movie was as surreal as this TV program but unfortunately it’s as bland and directionless as Nina herself.

And boy is it directionless. There aren’t any subplots in the movie, no cause and effect, no acts, no structure, no flow; only scenes that happen, and I can’t even find any reasons for the order in which they happen. The scenes also don’t start or end; they just interrupt each other, not leaving any emotional impact. For example, there’s a scene where Nina sees her future self. She’s on one of those midnight walks with the good boy Homer when she sees a couple being romantic. The woman is wearing a long red dress, and the man is in all black. The shot is wide, so it’s impossible to see their faces, but the woman is obviously Nina:

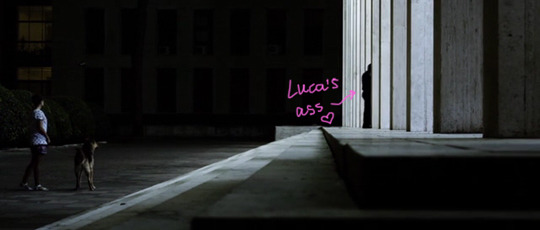

And the man is definitely Luca. I recognized his ass. I’m not joking, guys. It’s his ass:

Also I was later directed to the website of the photographer who took the set photos, and yes, it’s Nina and Luca.

I never forget an ass.

Anyway, Nina, who at this point hasn’t properly met Luca’s character, Fabrizio, sees herself from the future acting romantic with him, and doesn’t react. We don’t even know if she recognizes herself or him or whether it’s even a real scene or a dream. How are we supposed to empathize with a heroine who isn’t allowed to react to her environment?

Whatever, it’s time to talk about Fabrizio. He plays the cello and he’s obnoxious. That’s it. He first appears as a patron of Caffé Palombini, the real-world café Nina frequents (and buys her cakes at). She’s drinking her usual milk shake and reading. At some point, their eyes meet, but neither says anything, and then Nina gets up and runs after the good boy Homer who decided to take a little stroll by himself. She leaves all her things behind: her milk shake, her handbag, at least three books, a whole stack of paper for calligraphy, and her diary. It’s obvious she’s going to come back as soon as she gets the dog. And yet before her feet are even out of frame, Fabrizio gets up, goes to her table and fucking steals her diary!

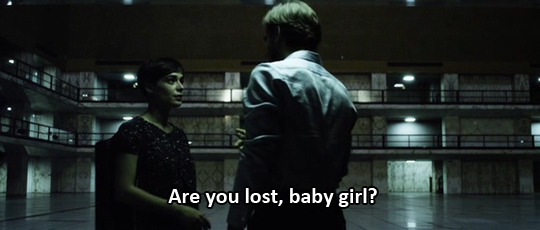

His next several appearances are random and sporadic, and it looks like he’s stalking Nina, but by the time of his first actual scene she is following him for some reason. Obviously, he can’t let a woman outcreep him, so he ambushes her:

He tells her blankly, “You’re following me,” but I think this scene deserves better dialogue. Thankfully, we have a whole well of predator/maiden media to pull from.

Though I personally believe this is the most appropriate line:

Fabrizio lets Nina know he has her diary in the dickiest way possible: he quotes from it to let her know that he’s read it. He then informs her that he’ll only give it back to her if she continues following him. And it’s not blackmail; “it’s an agreement.” What an asshole! I’m weeping for the dignified cuckoldry of Joseph.

And what was the purpose of that “agreement” plot point if the next time they meet is by chance? Quirky love interest writing, duh. So quirky that the accidental meeting happens when Nina is walking past a phone booth where Fabrizio is… doing a phone prank? I don’t know, I got nothing. Anyway, he’s annoyed their meeting is unintentional on Nina’s part, but he returns her diary, and I guess they start dating? He watches her sing once with what could only be described as a complete absence of emotions:

In the next scene she watches him play the cello after which they go on a date. Nina is wearing the red dress from the vision, but Fabrizio’s shirt is different. I fucking give up.

Their next (second?) date is a romantic dinner on Nina’s roof, and they’re dancing for entirely too long. She then tells him she’s scared of how much she’s enjoying his company, gives him a ridiculously chaste kiss goodnight and… completely ghosts him afterwards. And if you didn’t dislike Fabrizio before, you will now as he starts calling Nina at ungodly hours (including 5:30 am) and leaving her very whiny and increasingly more passive-aggressive, entitled, and accusatory voicemails. At some point he even leaves a voicemail for the fucking dog! He’s like, “Homer, I’m worried, meet me at the café.” Again, quirky love interest writing: extortion, phone pranks and a voicemail for a dog.

Fabrizio then lets Nina know he’ll be leaving town in three days in case she’d like to see him one last time or whatever. And she never fucking does! In any other movie she’d be chasing through the airport, but here she just drops him like he’s a well-tucked shirt! She tells the kid she’s befriended (she hangs out with an eleven-year-old boy the whole movie, don’t worry about it) that she’s afraid to be “like everyone else”, with a job and a boyfriend, so she doesn’t even say goodbye to Fabrizio. At some point she goes for a walk with the good boy Homer, and Fabrizio is also there, and they just miss each other. Even fate isn’t interested in that romance.

And then all the fascist buildings get covered in gigantic paper figurines, and the red-dressed Nina runs into Fabrizio’s arms. Because of course.

Nina is one of those movies where the main theme — a struggle to grow up — is obvious, but the rest of the elements are a mess only the writer-director could decipher. And I don’t really care. Again, I had to read Japanese postmodernists at university. What I do care about is the male form I mentioned at the start. I know I have no one but myself to blame for my expectations of how the director should have framed Luca’s body or face, but it’s one thing to frame him blandly and a completely different thing to isolate him as the only character (or actor) she’s deeply uninterested in filming competently. Everyone else in the movie gets their fair share of close-ups and decent lighting whilst Luca — whose name is literally second in the credits — gets, um, neglected.

This is his introduction:

These are literally all his close-ups:

Should I even count this last one? What’s with the lighting? Like, this is as well-lit as his face gets:

Oh, the shot is too wide and you can’t see his face properly? Well, tough poop:

Are you kidding me with this shit?

Nina may not be objectively the most terrible of the movies Luca’s been in: I’d argue both Mary of Nazareth and L’ultimo terrestre are worse, as is Slam, whose time’s a-coming. Nor is it the movie where Luca appears the least (The Great Beauty’s literal one minute of screen time is saying hi). But it’s the only movie I have no reasons to watch: it’s blandly shot, poorly structured, badly themed — and it’s actively obstructing Luca’s beauty and charisma. So no matter which film you’ll ask me to do next, at least in terms of the visual component of my posts, we have nowhere to go but up.

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

#hes ancient and evil!! hes a rich bitch in a castle lording over the peasants! and theyre New Money from the rising middle class#who acquired their wealth through the hard work of *checks notes* dead mother dead father dead mentor and i guess ambiguous texas methods#lets start the book again but i take a shot for every thematic inconsistency and pass out before Jonathan even meets the count#im being mean but also. dracula is frustrating because any time you think 'oh thats compelling' it gets contradicted two chapters later#yes im aware that inheriting is not equal to waging war but the class lines being delineated are very wonky (OP’s tags)

Bram Stoker really made a point of the Count hoarding old money in his bedroom like a dragon, the spoils of war and empire guarded by the upper class, just for his heroes to bribe their way across Europe funded by their inheritance from a revolving door of dying parents, huh

#ah yes but it's DIFFERENT because he's Eastern#somehow#(I am sure you Know OP I just gotta vent you get me)#it's really so incredibly hypocritical#eps. when Arthur IS inherited aristocracy!! ffs#there was DEFINITELY war in that background check!!!#otoh I have seen nothing yet to convince me that Quincey isn't rich off Showbiz Cowboy Life#this is my headcanon I'm sticking to it til Stoker breaks it#if he bothers#Draculee Dracula

706 notes

·

View notes