#journal: the englishwoman's domestic magazine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Fashions - August 1855

There is this month nothing new in the fashionable world—that is to say, so far as dress is concerned. Things remain exactly as they were, except the introduction of the new broad-brimmed straw hat. It is prettily called the Pamela Hat. Pamela Hats were at first worn only by children and young ladies, but they are now being adopted by ladies of all ages. They (the hats, not the ladies) are generally made of Leghorn, quite flat; the brim broad, and slightly curving down over the forehead. They are trimmed underneath with a profusion of wild flowers, roses, and rosettes of ribbon, with long white strings. The outside is trimmed with a narrow garland, or wreath of flowers, intermingled with bows of ribbon, terminating at the back (generally) with long flowing end. When the hat is brown, the ribbons are, of course, to match, with few flowers, and those red.

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, August 1855, p.145. [x]

#1850s#journal: the englishwoman's domestic magazine#19th century fashion#19th century#1855#historical fashion#1850s fashion#womenswear: accessories#womenswear: headwear#womenswear: hats#headwear: hats#headwear: pamela hat#material: leghorn#material: flowers#colour: brown#colour: red#material: ribbons#material: straw#the fashions

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The fantasy of a woman exhibiting and disciplining another woman’s body attained its most spectacular form not in the visual images but in the printed pages of England’s leading fashion magazine. In 1868, almost every fashion plate in the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine included a girl alongside two adult women, and that same year a debate raged in letters to the editor about whether parents, especially mothers, should use corporal punishment to discipline children, particularly girls past puberty. The fashion plate’s image of the quietly contained, fashionable girl who worships her female elders became a story of unruly daughters and stern mothers. The fashion image’s obsession with dressing and covering the body became the reader’s drive to expose it; the proud mien of the plate’s figures mutated into narratives of humiliation and shame.

Only one element remained constant from image to text: the world in which both rituals were staged was dominated by female actors and objects. “I put out my hands, which she fastened together with a cord by the wrists. Then making me lie down across the foot of the bed, face downwards, she very quietly and deliberately, putting her left hand around my waist, gave me a shower of smart slaps with her open right hand. . . . [R]aising the birch, I could hear it whiz in the air, and oh, how terrible it felt as it came down, and as its repeated strokes came swish, swish, swish on me!” This description of a girl being birched by a woman first appeared in an 1870 supplement to the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine that extended a debate about corporal punishment raging in the journal since 1867.

Editor Samuel Beeton justified publishing the monthly supplements, each consisting of eight large, double-columned pages of small type, by citing the overwhelming volume of letters received on a topic “which, of late years,” had “aroused . . . intense, not to say passionate interest.” Beeton priced the supplement at two shillings and made it available by post, thus guaranteeing its accessibility to middle-class readers. Like the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, a respectable family publication that advertised in the pages of Cobbin’s Illustrated Family Bible, the supplement presumed an audience of housewives who would be drawn to its advertisements for Beeton’s Book of Home Pets and The Mother’s Thorough Resource Book.

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, as its title announced, was aimed at the middle-class women whose homes defined the nation. By the 1860s, the thirty-two-page monthly cost sixpence and reached roughly 50,000 readers per issue. With two color fashion plates in each issue, a republican editor who supported women’s employment and suffrage, and articles on “The Englishwoman in London,” “Great Men and Their Mothers,” and “Can We Live on £300 a Year?” the journal combined fashion, feminism, and thrift. Fashion magazines had always had heterogeneous content—astronomer Mary Somerville first encountered algebra while reading “an illustrated Magazine of Fashion”—and the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine prided itself on being learned and political as well as practical and stylish.

The magazine had both women and men on its staff, and Isabella Beeton codirected it with her husband until her death in 1865, soon after she completed a best-selling opus on household management. The publication of correspondence revealing women’s preoccupation with corporal punishment and its overlap with pornography might surprise us today, but only because we erroneously assume that Victorians imagined women and girls to be asexual unless responding to male initiative. Victorians themselves did not set such limits on female desire, and many found the letters on corporal punishment published in the eminently respectable Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine provocative, with their use of onomatopoeia, teasing delay, first-person testimony, and punning humor, all typical of Victorian pornography.

A letter from “A Happy Mother,” published in 1869, explained that the author put cream on her children before whipping them, so that punishing them produced whipped cream: “I scream—ice cream.” Some readers denounced the correspondence as indelicate and indecent, warning that it might arouse male readers, and accusing women who flogged children of improper motives. In the 1870 supplement, a “mother” worried about how a gentlemen might respond to finding an otherwise “useful” publication marred by “immodest” descriptions of punishments by “ladies.” One letter fulminated against “people who take pleasure in giving . . . exact details of the degrading way in which they punish their children.”

A correspondent signing “A Mother Loved By Her Children” condemned “the indelicacy in which every disgusting detail is dwelt on” by a woman who described a punishment she had received from another woman. “A Lady” protested “the offence to decency and propriety in publishing vulgar details” about “the removal of clothes and ‘bare persons.’” Readers who protested the indecency of the letters recognized that reading about punishment could provoke sexual sensations in both men and women. The voluminous correspondence began as a short query in 1867: “A Young Mother would like a few hints—the result of experience—on the early education and discipline of children.” The first two published responses opposed whipping, arguing that mothers who resorted to physical punishment would lose the self-control needed to discipline children properly.

Though Beeton himself opposed corporal punishment, he published many letters in favor of it. The debate quickly became more specific: whether it was proper for adult women to punish girls, especially those past puberty, by whipping them on the “bare person.” Whether writing for or against corporal punishment, correspondents provided detailed accounts of inflicting, receiving, and witnessing ritual chastisements in which older women restrained, undressed, and whipped younger ones. Letters described mothers, aunts, teachers, and female servants forcing girls and young women to remove their drawers, tying girls to pieces of furniture, pinning back their arms, placing them in handcuffs, or requiring them to count the number of strokes administered.

…Corporal punishment is where pornography, usually considered a masculine affair, intersects with fashion magazines targeted at women. Both types of publications were mass-produced commodities that created an aura of luxury, and both depended on the relative democratization inherent in an economy organized around consumption and leisure. Pornographic publications and monthly women’s journals had similar formats: both combined short stories, poems, historical essays, serial fiction, current events, and letters to the editor; both featured detachable color prints that could be sold separately; and both released special Christmas issues. Their common interest in corporal punishment led to even more concrete links between pornography and fashion magazines.

John Camden Hotten, the publisher of many pornographic works, advertised a pseudoscientific study of Flagellation and the Flagellants in the supplement to the Englishwomen’s Domestic Magazine. Other pornographic publications actually reprinted verbatim material first published in fashion magazines. In his exhaustive bibliography of pornography, Henry Spencer Ashbee mentioned the “remarkable and lengthened correspondence” about flagellation in “domestic periodicals” alongside his discussion of flagellation in “bawdy book[s]” such as Venus School-Mistress and Boarding-School Bumbrusher; or, the Distresses of Laura. The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine was more available to women readers than pornography, but Victorian pornography was not the exclusively male province it is often assumed to be.

Like the fashion press, pornographic literature expanded during the middle decades of the nineteenth century; between 1834 and 1880, the Vice Society confiscated 385,000 prints and photographs, 80,000 books and pamphlets, and 28,000 sheets of obscene songs and circulars. Who wrote and read pornography remains a mystery: publishers falsified dates and places of publication; authors wrote under pseudonyms; and individuals left few public traces of their purchases and reading experiences. The scant evidence we have suggests that pornography was a predominantly but not entirely male domain.

Newspapers reported women publishing and selling obscene books and texts; one woman has been documented as the author of a French pornographic novel that circulated in England; and women of all classes frequented the Holywell Street area where obscene books and prints were sold and often visible in shop windows. After publisher and bookseller George Cannon died in 1854, his wife ran the business for ten more years; in 1830 a police officer testified that Cannon hired women who “went about to . . . boarding schools . . . for the purpose of selling” obscene books, “and if they could not sell them to the young ladies, they threw them over the garden walls, so that they might get them.”

Women did not have to purchase pornography directly to read it, however, since they might easily find any sexually explicit books that male family members brought home. Women did not need to turn to pornography to encounter sexually arousing descriptions of older women disciplining younger girls; they could read material in the pages of a ladies’ home journal that would be reprinted as pornography. The correspondence about corporal punishment blurred distinctions not only between pornography and the women’s press but between male and female readers. Some worried that the magazine had become so obscene that it needed to be hidden from both; Olivia Brook wrote in 1870 that she now put the magazine “out of reach of any casual observer, and where especially no gentlemen can read it.”

…In The Other Victorians, Steven Marcus influentially argued that all pornographic accounts of whipping, even those that represent women birching or being birched, were nothing but displaced versions of repressed fantasies about father-son sex. That interpretation assumes that erotic desire between women was irrelevant to Victorian society, and that sex between men or family members was impossible to represent directly. In fact, the only impulse Victorian pornography repressed was repression itself. Victorian pornographers represented same-sex acts of all kinds and freely indulged their obsession with incest, including sex between fathers and sons.

…Victorian pornography helps to explain how the family could simultaneously be organized around sexual difference and be a site of homoerotic desire, for in it the family is a hotbed of sex, but same-sex acts do not imply fixed sexual identities. Representations of sex between men and sex between women were never confined to specialized publications. Sex between women was regularly featured in pornographic texts and in images that depicted two or more women engaging in tribadism, oral sex, anal sex, digital penetration, mutual masturbation, and sex with dildos. Flagellation literature described women achieving orgasm from punishing girls and penetrating girls with fingers and dildos while birching them.

…The convergence of pornography and women’s magazines on the topic of flagellation points to their common origins in nineteenth-century liberal democracy, which promoted the free circulation of ideas among individuals who could demonstrate self-control and tasteful judgment. Pornography had affinities with Enlightenment and utilitarian ideals regarding the empirical investigation of nature and quests for knowledge, increased well-being, and merit-based rewards. Fashion was a feminized version of liberal democracy, for it depended on a woman’s ability to train her taste and accommodate her individual style to fluctuating group rules.

By following fashion codes, women learned to fit their bodies into a social mold; by improvising on those codes, as fashion itself demanded, women developed the kind of restricted autonomy associated with liberal subjectivity. As Mary Haweis explained in The Art of Beauty (1878), clothing was a form of individual aesthetic expression and therefore had to follow “the fundamental principle of art . . . that people may do as they like.” The liberty underlying the art of dress also upheld of liberalism’s ideal of personal freedom as a source of originality and political renewal. The correspondence columns of fashion magazines allowed women to participate in the public discourse central to liberal politics.”

- Sharon Marcus, “Dressing Up and Dressing Down The Feminine Plaything.” in Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

HISTOIRE DU MAGAZINE DE MODE

Fashion magazines are an essential component of the fashion industry. They are the medium that conveys and promotes the design's vision to the eventual purchaser. Balancing the priorities has led to the diversity of the modern periodical market.

It wasn’t until 1732 that the actual word “magazine” was introduced (thanks to bookseller Edward Cave). It was under the reign of Louis XIV in France when the term “fashion magazine” made its initial emergence. The fashion publication was called The Mercure Galant and featured illustrated fashion plates of what the aristocracy was wearing. This made it possible for dressmakers who lived outside of the court to have an idea of what was “trending” in royal fashion.

Reference- https://fashion-history.lovetoknow.com/

youtube

youtube

youtube

Check out the complete series of Vogue by the decade series.

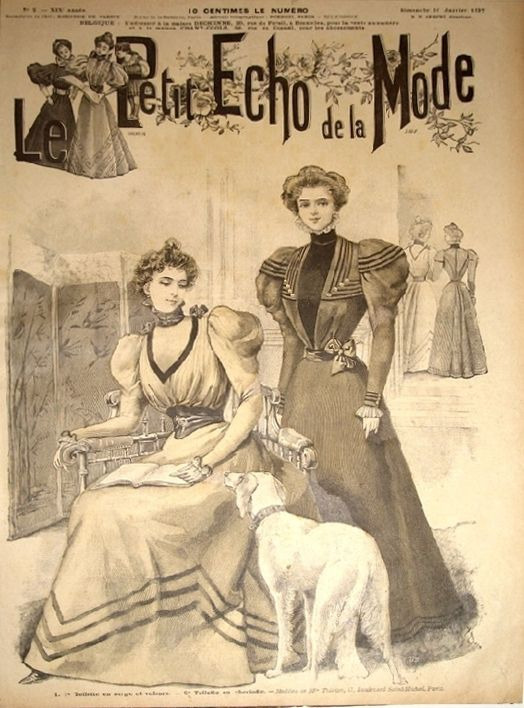

In 1678, however, Donneau de Visé first included an illustrated description of French fashions with suppliers' names in his ladies magazine, Le Mercure galant, which is considered the direct ancestor of modern fashion reports. Thereafter, fashion news rarely reappeared in periodical literature until the mid-eighteenth century when it was included in the popular ladies handbooks and diaries. Apparently in response to readers' requests, such coverage to the popular Lady's Magazine (1770-1832) was added to the genteel poems, music, and fiction that other journals were already offering to their middle-class readers.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Lady's Magazine had been joined by many periodicals catering to an affluent aspirational society. Interest in fashion was widespread and it was included in quality general readership journals such as the Frankfurt Journal der Luxus und der Moden (1786-1827) and Ackermann's Repository of the Arts, Literature, Commerce, Fashion and Politics (1809-1828) as well as those specifically for ladies. Despite the continental wars, French style was paramount and found their way into most English journals. Very popular with dressmakers was Townsend's Quarterly (later Monthly) Selection of Parisian Costumes (1825-1888), beautifully produced unattributed illustrations with minimal comment. The journals were generally elite productions, well illustrated and highly priced, though cheaper if uncolored. John Bell's La belle assembléé (1806-1821) was edited by Mary Anne Bell between 1810 and 1820, also proprietor of a fashion establishment. Dressmaker's credits are rare, perhaps because fashion establishments were dependent on personal recommendation and exclusivity.

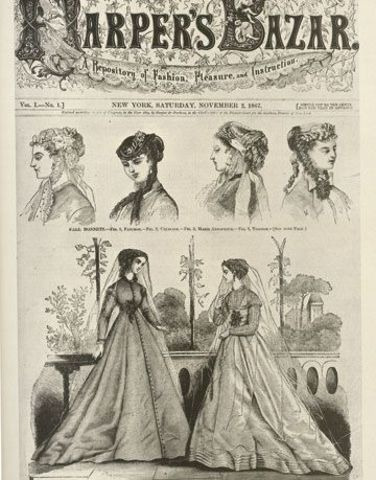

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the magazine, like other popular literature, profited from improvements in printing methods, lower paper costs, and lower taxation. Literacy levels had risen and readership increased. Many new titles were produced and fashion for all types and ages were generally included in those for the women's market. Circulation figures were high; Godey's Lady's Book (1830-1897) issued 150,000 copies in 1861 and Samuel Beeton's The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine (1852-1897) issued 60,000. Advertisement increased but the revenue rarely inhibited editorial independence. The key to circulation was innovation, and Godey and Beeton both added a shopping service and additional paper patterns to those already available within the magazine. Up-to-date fashion news was an essential and fashion plates as well as embroidery designs came direct from Paris sources, though in America they were often modified for home consumption.

High-fashion Paris news was most easily accessible in the large format society journals, the weekly illustrated newspapers, and La mode illustrée (1860-1914), of which there was an English edition. Semi-amateur fashion cum gossip columnists were a feature of Gilded Age society, but the couture concerned with their expanding international market were increasingly professional about their publicity, and well-kept house guard books were probably as useful for press promotion as they were to designers and clients.

Through its Chambre Syndicale, the couture was organizing its own fashion journal, Les modes (1901-1937). Its innovative and informative photographic illustrations made it an anthology of high status Paris design by the end of the century. In 1911 Lucien Vogel offered the couture an even more modern shop window in the elitist Gazette du bon ton (1911-1923), the precursor of the small pochoir (stencil) illustrated fashionable journals characteristic of the avant-garde press of the early twentieth century.

Industry Growth in the 20th Century

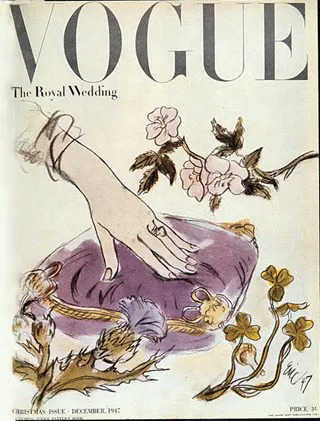

As fashion pace increased, the fashion publication scene was stimulated by developments at Women's Wear Daily (WWD), after the Fairchild family purchased it in 1909 as a conventional trade paper for the garment trade. Its offshoot, W (1972- ) was developed by John Fairchild, the son of the founder, to have "the speed of a newspaper … with the smart look of a fashion magazine" and significantly, its survival depended on advertisement. News "scoops" were competed for ruthlessly. Vogue secured the designs for Princess Elizabeth's wedding dress in 1947, WWD obtained Princess Margaret's in 1960, plus the annual Best-Dressed List. Assessment of style change was more problematic and it was the role of the fashion editor to balance designer's contribution and public acceptance. It was a tribute to both when magazines and public supported Dior's New Look in 1947.

Increasingly dependent on advertising, the conventional magazine is challenged if fashion deviates from established trends. The "lead in" time for a quality, full-color journal is generally two months-too long for the speed of street fashion and its high-spending, young, and trendy clientele. This readership was not targeted until 1976 when Terry Jones, originally from Vogue, developed the U.K. magazine i-D, with its apparently spontaneous fanzine look. Its original message, "It isn't what you wear but how you wear it," had little appeal for the clothing trade but it has found its niche market in the early 2000s and is the prototype "young fashion" magazine.

Check out books and more at- https://amzn.to/3r10gRd

Also browse your fashion favorites at- https://amzn.to/34hrNUB

#fashion#fashionknowledge#fashionhistory#fashionblogger#fashionblog#fashionblogstyle#fashionblogpost#fashionblogdaily#blogoftheday#twiggy#vogue magazine#harper's bazaar#fashion_photography#fashion magazine#audrey hepburn#fashion_illustration#fashion industry#fashioncrux#teammodafactor#trends & celebrity style#fashion_crux

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

the whole Victorian nipple piercing thing

you’ve probably seen it on a hundred “things your history teacher didn’t want you to know!!!!” posts:

“there was totally an 1890s trend of women piercing their nipples! omg those dirty, dirty Victorians!”

my take on this is that probably like two or three particularly bohemian ladies did it, the press got hold of the idea, and those stellar late 19th century journalistic standards blew it way out of proportion. and yeah, “a nonzero number” is still more Victorians than most people expect to have had nipple rings, so the reaction nowadays would likely be the same even if it wasn’t painted as a huge trend

but because I’m me, the idea of someone being Wrong About History On The Internet still gets under my skin. so I did some research

besides a few medical journals loudly decrying the practice, the most often-cited period source on “bosom rings” is a series of letters in the magazine English Mechanic and the World of Science

sounds like a steampunk Harry Potter book title. let’s venture

the April 1888 edition included a letter, allegedly from a Polish man named Jules Orme, about how he and a friend got their nipples pierced as teenagers. and one response letter claimed to be from a woman, Constance, whose fiance/cousin (ah, the 1880s) now wanted her to have hers done after reading Orme’s account

before we go any further, I have to talk about 19th-century tightlacing erotica

any pop history discussion of the corset controversy will undoubtedly include letters written to a variety of periodicals, mostly The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, by women laced down to 15″ or even 13″-waists who were quite fond of the practice. REALLY fond of it. using the phrase “delicious agony” fond of it. describing in detail the strict headmistresses and stern aunts who ordered them laced down and devised overly complicated ways of ensuring they couldn’t remove the corsets fond of it. and shortly thereafter, the same magazine started publishing very detailed letters about whipping maidservants and pretty young wives

if you’re thinking that sounds like BDSM porn, yes. yes, it does. and given the dearth of 13″ extant corsets that have been found, that’s probably exactly what it was. so there was a long tradition of using magazine correspondence pages as the proto-Penthouse by the time the nipple ring discussion commenced

“Constance” receives a reply from “Fanny,” a young lady whose nipples have been pierced for five years “at the request of an intimate friend.” allegedly this request and the piercing happened when she was 15, a detail which makes the letter read less “actual reality of a girl/woman’s life in the 1880s” to me and more “skeevy youth-fetishizing porn”

the conversation goes back and forth for a while, and then. and then.

“Constance” and her younger sister actually go to get their nipples pierced and describe the process in detail. allegedly.

this post is getting rather long, so click here for Part 2!

(source on the fetish letters in The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine. cw for mention, but no images, of illustrations fetishizing slavery)

(source on the nipple-piercing letters. take this blog with a grain of salt; I’m only using it for text, names/pseudonyms, and dates)

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi hello it is me Professional Stuff-Knower About Victorians. here to both debunk and Make It Weirder, by turns:

1. Nipple piercings were probably not common. The main “source” on that is a series of borderline fetishistic anonymous letters to like one scientific journal in the 1880s, and while one letter does contain a description of nipple-piercing at a Paris jewelry store, it’s functionally identical to professional ear-percing at the time (just, you know. with nipples). So we really have no idea if the letter was true, or from the same skeezeballs who wrote to the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine pretending to be 17-year-old girls tightlaced by Cruel Headmistresses at boarding school. A few newpapers reported on the alleged trend, but they also claimed like every five years that the Hot New Thing For Ladies in Paris was dyeing one’s hair green. And it never was. Also I have never heard of surviving extant nipple rings, or any known erotic photos showing pierced nipples. So...

2. The baby will stop crying if you give it opiate-laced patent medicines. Your toothache will stop if you take cocaine. Big difference. (Also doctors knew of the dangers of both those things, but like. In the case of cocaine, they just didn’t have anything better in terms of painkillers, so they had to do the best they could. In terms of sketchy patent medicines- you know how hard it is to crack down on Flat Tummy Tea and activated charcoal everything nowadays? Yeah.)

3. The arsenic isn’t on your face. It’s in your stomach. Because one would usually eat arsenical wafers for the complexion rather than applying it externally, as far as I’ve seen. Yep: this one is actually worse than most people think. The saving grace is it was usually a tiny bit of arsenic only- though a mistake in compounding could prove fatal, and also why the fuck are you eating arsenic in the first place oh my god. A lot of people at the time thought this was stupid, too.

3b. The actual answer to Why is fucking bonkers: a medical article written in 1851 by one Johann von Tschudi claimed that the girls in some Alpine town had perfect skin because there was a weird local tradition of eating small quantities of arsenic and gradually building up an immunity. I am not joking. So the Gwyneth Paltrows of the day got hold of that information and went nuts.

4. Yeah no early electricity was the wild west and here is a video about Victorian fabric combustion by dress historian Nicole Rudolph (the latter was less of a risk while wearing a garment and more when the fabric was being stored, though. and if it caught fire, obviously). And to be clear, though, they did know about some of these risks and scramble to mitigate them. “They did in fact know and consider it a problem” is a running theme here.

5. Including lead toxicity. Yeah- they knew about that! I was uncertain, but I dug into it and there are a lot of articles from the Victorian era like Wow It Sure Sucks That We’re So Reliant On Something Deeply Toxic Literally All Around Us. Scientists Are Working On It But [shrug]

6. No notes on the asbestos thing either. That’s. Yep, that’s pretty accurate. The ill effects of asbestos were first noted in 1899, but it took ages for it to actually get taken seriously. As with many things.

7. Food adulteration was considered bad. Food adulteration was also difficult to avoid. People tried, but with regulations still in their infancy and few ways to test things (especially for the poor)... : D

8. Doctors: “hey maybe don’t leave your baby’s bottle nipple unwashed for three weeks like Mrs. Beeton says is okay?” Consumers: “[read 11:30 AM]”

9. Really my final takeaway is that they were aware of a lot more dangers of their world than we give them credit for. They just didn’t often have alternatives, so they had to do their best with what they did have. And sometimes they could avoid things but ignored warnings, because Humans Can Be Illogical.

We wouldn’t know anything about those ideas, now would we?

[cough]microplastics[cough]sketchycelebritydietsupplements[cough]

The Victorian Era was shite compared to now obsiously but also titty piercings were popular everyone was on heroin and they thought bad sex made your kids ugly so the zeitgeist must have been wild

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

Wo Bekomme Ich Kostenlose, Günstige Und Alte Zeitschriften Für Collagen

Inhaltsverzeichnis

DeBows Rückblick

Ideen Zum Sammeln: 6 Interessante Antike Und Historische Gegenstände Zum Sammeln

Sports Illustrated

Nachfolgend haben wir eine Liste der Orte zusammengestellt, an denen Sie alte Zeitschriften kaufen können, wobei wir mit den besten Möglichkeiten beginnen. "The Nation ist die älteste Wochenzeitschrift Amerikas und wird unabhängig herausgegeben. The Nation wendet sich an ein engagiertes Publikum und setzt sich für bürgerliche Freiheiten, Menschenrechte und wirtschaftliche Gerechtigkeit ein." - Die Zeitschrift The Nation. Das Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine wurde von Samuel Beeton, dem Ehemann von Mrs. Beeton, gegründet, die im 19. Jahrhundert für ihre Bücher über Haushaltsführung weithin bekannt war.

youtube

Die Zeitschriften aus den 1920er Jahren sind wie Gold.

Auktionshäuser können Ihnen helfen, höhere Preise für Ihre Zeitschriften zu erzielen, aber sie verlangen auch eine saftige Gebühr - wahrscheinlich etwa 25 % des Verkaufspreises.

Unsere Zeitschriften werden nach dem einzelnen Titel und nach dem Datum bewertet.

The Magazine Rack ist eine Sammlung digitalisierter Zeitschriften und monatlicher Veröffentlichungen.

Ich würde Ihnen sogar raten, nach Zeitschriften Ausschau zu halten, die vollständig und lesbar sind, aber aufgrund ihres schlechten Zustands sehr erschwinglich.

Aber das bedeutet nicht unbedingt, dass Sie die Bank sprengen müssen. Im Folgenden haben wir eine Liste von Stellen zusammengestellt, an denen Sie alte Zeitschriften zu günstigen Preisen oder sogar kostenlos erhalten können. Archiv für alte Zeitschriften, alte Zeitschriften pdf. Jahrhunderts für wohlhabende Menschen, die bequem außerhalb der Stadt lebten - oder zu leben versuchten. Diese Monatszeitschrift war in der Zeit vor dem Bürgerkrieg die auflagenstärkste Zeitschrift in den USA und erreichte 1860 eine Auflage von 150.000 Stück, obwohl sie teurer war als andere Monatszeitschriften.

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/VHOJ1PjcnX0/hqdefault_664933.jpg

DeBows Rückblick

Das Wort "Vintage" bezieht sich auf ein Objekt, das aus einer früheren Generation stammt. Solche Gegenstände werden oft sehr begehrt, wenn die Menschen älter werden und sich danach sehnen, sich an ihre Vergangenheit zu erinnern und sie wieder zu erleben. Ich bin zum Beispiel in den 1980er Jahren aufgewachsen, daher https://numberfields.asu.edu/NumberFields/show_user.php?userid=975800 neige ich zu Sammlerstücken aus den 1980er Jahren.

Zeitschriften, die sich mit Politik, politischen Themen und Kritik/Überblick über die Politik befassen. Einige Zeitschriften können sich mit "Nachrichten" und "aktuellen Ereignissen" überschneiden. Entdecken Sie eine riesige Auswahl seltener älterer Ausgaben von Magazinen, Zeitschriften und Journalen von Time und Life bis Vogue und Vanity Fair. Index von Zeitschriftenartikeln, einschließlich der vollständigen Abdeckung der gedruckten Originalbände des Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature. Die älteste Wochenzeitschrift der Welt, gegründet 1828 von dem schottischen Reformer Robert Stephen Rintoul. " - Wikipedia. Sie existiert noch im Jahr 2021. Archiv alter Zeitschriften, Archiv alter Zeitschriften.

Ideen Zum Sammeln: 6 Interessante Antike Und Historische Gegenstände Zum Sammeln

Gesammelte Links hier bei Century Past zu ausgewählten Fotosammlungen aus den späten 1800er und frühen 1900er Jahren in Ländern rund um die Welt. Ähnelt in Aussehen und Inhalt dem Delineator und dem Ladies' Home Journal und ist wie diese in von Frauen besuchten Lesesälen beliebt. Dieses monatliche Fan-Magazin, das sich mit der Filmindustrie befasst, erschien ab 1930 und wurde mit einigen Änderungen bis 1977 fortgeführt.

Im Jahr 1961 wurde die Zeitschrift in Car and Driver umbenannt, um einen allgemeineren Fokus auf Autos zu zeigen. 2005 feierte die Zeitschrift ihr 50-jähriges Bestehen. Unsere Zeitschriften werden einzeln geprüft und Ihnen nur angeboten, wenn sie unseren hohen Ansprüchen genügen.

0 notes

Text

Murder, Maps, Mansions

This month sadly saw the last issue of IndiePicks Magazine. Below are the last of the mystery reviews I did for IndiePicks. They include one of my favorite books of this spring--Sujata Massey’s The Widows of Malabar Hill; historical fiction is not usually my thing, but I found this one a cut above the rest. Recently I also reviewed some non-mystery titles, including the outstanding Where the Animals Go (maps and infographics...you can’t go wrong) and The Country House Library, a look at the best appointed home libraries of old in Ireland and Britain.

IndiePicks Magazine

The Widows of Malabar Hill. Massey, Sujata. Soho House, $17.95, 9781616957780. The Widows of Malabar Hill is set in 1920s Bombay, where the city’s first female lawyer, Perveen Mistry, finds her gender for once working in her favor. Her lawyer father’s client dies and his three widows, Muslims who live in seclusion from the outside world, need representation. Perveen is a Parsi Zoroastrian, not a Muslim, but she’s compassionate and her kind nature and smarts are put to the test as she tries to help women who find themselves unprotected and in great danger. Over the course of the novel, readers also travel back in time to a few years before, when Perveen engages in a forbidden romance, a period that brings Parsi traditions to the fore. Those who enjoy stories about women using their wiles to make it in tough situations will relish this layered story and find a favorite character in Perveen, while soaking in the details of colonial-era India. This is one to give patrons who enjoyed Suzanne Joinson’s A Lady Cyclist’s Guide to Kashgar, which is set in a different place but the same era and has a similar feel. The Black Painting. Olson, Neil. Hanover House, $24.99, 9781335953810. It’s not exactly your traditional romance, but a years-long hidden affair is just one aspect of the supernaturally tinged family drama in The Black Painting. The book opens as a group of cousins, close as children but now living separate and far-flung lives, gather at their grandfather’s old-money Connecticut mansion. The patriarch has just been found dead, his horrified face staring at an empty space on the wall that, before its theft years ago, was home to the Black Painting. The painting, a Goya masterpiece, was rumored to be cursed—anyone who looked at it would go insane and meet a horrible end. Is that what happened to the grandfather? Who’s going to get his money? Where’s the painting now? And finally, can this dysfunctional, greedy clan get along for even the short time it will take to sort this all out? Olson deftly creates a festering family dynamic with psychological twists and turns that complement the supernatural element of the story, keeping readers wondering to the end as they try to unravel this family’s contorted relationships and buried past. The painting in the story is a real one; book groups that try this tale could pair it with Stephanie Stepanek and Frederick Ilchman’s Goya: Order & Disorder.

Dying Day. Edger, Stephen. Bookouture, $8.99, 9781786812704. Subtitling your book “Absolutely Gripping Serial Killer Fiction” means you’d better come through and Dying Day doesn’t disappoint. This second in the Detective Kate Matthews trilogy sees the Southampton, England police detective on the trail of a serial killer while trying to atone for the misjudgment that she believes led to the death of a young colleague. The guilt is crushing, and Matthews will do almost anything to catch this man, including put her life and career on the line. The trope of a detective who has to go it alone because nobody else cares enough could come across as well worn, but Matthews is a highly relatable character whom women who work too hard will see themselves in, and her quest to make things right is as compelling as the hunt to find the killer. The solution to this puzzle is unpredictable, too, making Dying Day an absorbing trip that readers won’t forget. This is a great readalike for Belinda Bauer’s The Beautiful Dead, another novel that stars a determined young woman on the heels of a monster.

In the Shadow of Agatha Christie: Classic Crime Fiction by Forgotten Female Authors, 1850-1917. Klinger, Leslie S. Pegasus, $25.99, 9781681776309. Only the Bible and Shakespeare have sold better than Agatha Christie’s books, says the introduction to In the Shadow of Agatha Christie, but the authors included here set Christie’s stage. The introduction—which provides an extensive early-mystery reading list—also explains what is hard to imagine now: mystery as a genre barely existed until the establishment of a professional English police force in the mid-nineteenth century. Highlights here include “Traces of a Crime,” an Australia-set police procedural by Mary Helena Fortuna, the first woman to write detective fiction. It’s fascinating to see the detective protagonist struggle to find a killer with only the most rudimentary tools and forensic knowledge at his disposal. In another standout tale, L.T. Meade—many female authors of the time used initials or pseudonyms, were anonymous, or were simply uncredited—and coauthor Robert Eustace introduce the social minefield surrounding an heirloom pearl necklace that a disreputable woman has her eye on. A main character in this tale has the shocking habit of wearing her evening dresses too high at the neck, which telegraphs what readers are in for here: stories that delightfully show what made a page-turner in the nineteenth century and the birth of domestically set mysteries of today.

Booklist

The One. Marrs, John (author). Feb. 2018. 416p. Hanover Square, hardcover, $ 26.99 (9781335005106); e-book (9781488084874). First published December 1, 2017 (Booklist). In this mystery with an SF twist, it’s the present day, but the world has been radically changed by a new kind of dating service: Match Your DNA, which pairs love-seekers with the one person in the world who is their genetic soulmate. It sounds perfect at first, and many couples worldwide are blissfully happy with their match, but the downsides are considerable. What if your match is decades younger or older, or he or she lives in a far-off country? What if you’re already married when you’re notified that your match has been found? The possibilities can become knotty, and they’re well illustrated by the several people featured in Marrs’ alternating chapters, among them a young Englishwoman whose match is in Australia, an engaged couple who didn’t meet via Match and fear their test results, and a career-focused scientist who wants to find love at last. Complicating the story still further is a serial killer who uses dating sites to find his prey. Marrs’ engrossing, believable thriller raises intriguing questions about our science-tinged future.

Library Journal

The Country House Library. Purcell, Mark. Yale University Press. 9780300227406. Purcell (deputy director, Cambridge Univ. Library; formerly libraries curator, National Trust) meticulously portrays dozens of libraries throughout Britain and Ireland in what is or was a private home (some are now museums). In an introduction that sets the tone for the book, Purcell carefully defines a "country house library"; like the rest of the work, each sentence has been deliberated at length and is packed with meaning and references. Thereafter are chapters that each cover a trend in country home book collecting over the past 2,000 years, starting with the likelihood of villa libraries in Roman Britain and continuing through today, when the dwindling fortunes of the aristocracy and the politics surrounding wealth have meant a certain amount of downsizing. The trends are illustrated by top-quality photographs and charts of the libraries and reproductions showing some of their treasures. The back matter is also impressive and includes a lengthy notes section and thorough index. VERDICT Libraries covering British or Anglo-Irish history, library science, and architecture are encouraged to acquire this gorgeous volume.

Where the Animals Go: Tracking Wildlife with Technology in 50 Maps and Graphics. Cheshire, James & Oliver Uberti. Norton. 9780393634020. This gorgeous data trove is refreshing in its admission that scientists are nowadays awash in the flood of information that comes from animal tracking devices and methods, and that even that is a fraction of what could be collected. Cheshire (geography, Univ. Coll. London) and Uberti (formerly senior design editor, National Geographic; both, London: The Information Capital) are relative amateurs in a field that doesn't even have a fixed name yet come across as pleasantly wonderstruck by the technology involved in, and the results of, animal tracking work. They impart earnest accounts of scientists' endeavors and some of the individual subject creatures involved. Accompanying the text are beautifully designed four-color maps and other visualizations that illustrate some of the breakthroughs that have been made using this newly found information—one map shows, for example, how the Ethiopian government had to redraw the boundaries of a giraffe conservation park after tracking data made it clear that the giraffes lived elsewhere. VERDICT The illustrations and step-by-step data-collection efforts combine to create an inspiring introduction to an important area of science.

School Library Journal

Festival of Color. Sehgal, Kabir and Surishtha Sehgal. S&S. Beach Lane. 9781481420495 PreS-Gr 3—Brother and sister Chintoo and Mintoo are getting ready for Holi, the Indian festival of colors. Their process is slowly revealed as the siblings gather petals, dry and separate them, and then crush the dried petals into powders. Lively digital illustrations show the children's excited family members and neighbors carrying the powders through the streets, and then "POOF!" wet and dry powders fly through the air in a rambunctious celebration. Readers will learn from the book's endnotes that Holi celebrates "inclusiveness, new beginnings, and the triumph of good over evil." This is useful information, but the real beauty of this attractive book is that it shows the country's home life and community togetherness beyond the holiday celebration. Children in primary grades will find this an accessible read, whereas younger patrons can enjoy it as a read-aloud and learn about colors and cultural festivals in an engaging way. VERDICT A must-buy for picture book sections that will delight children regardless of their familiarity with the holiday. Cool Cat Versus Top Dog. Yamada, Mike. Frances Lincoln. 9781847807380. Preschool-Gr 1—All year long, Cool Cat and Top Dog tinker, tweak, and polish their race cars to perfection until it's time for the annual showdown the Pet Quest Cup. Each competitor has an arsenal of tricks ready on the big day: this time, Cat has her Bone Bazooka, while Dog's packing the fearsome water gun Soggy Moggy. Something's different this year, though—the competition takes a twist when the sometime-rivals work together and are joint winners. Don't take this for a preachy tale about cooperation. The competition is cutthroat and resorting to shenanigans to win by any means necessary is hardly an exemplary message. Nonetheless, the lively text keeps the suspense running high and action-packed illustrations featuring expressive animal characters will hold little readers' interest until the end. VERDICT An exciting choice for children who are fans of car races and readers who have outgrown Penny Dale's Dinosaur Zoom Pigín of Howth. Kathleen Watkins. Dufour Editions. 9780717169726. Pigín (pronounced "pig-een" and meaning "little Pig") enjoys three adventures in this gentle and colorful look at life in a well-to-do Irish seaside town. Pigín lives in the fishing village of Howth in a cozy house overlooking the sea. He spends his days enjoying friendship with Sammy Seal, Sally Seagull, and other animals, as well as some human pals. The three stories depict Pigín learning to swim, going for a magical picnic with fairies, and dressing up to go to the horse races. While the dialogue can be clunky in places, the tales are a little reminiscent of what Paddington and Lyle the Crocodile get up to, with love and friendship complemented by the odd, nutty activity. Suggs's striking watercolors are up to the task, depicting the Irish town, its inhabitants, and the child and animal characters with colorful aplomb. VERDICT This is sure to be a hit in Ireland as Watkins is well known there—in her own right as a harpist but also as the wife of one of Ireland's most beloved celebrities, the broadcaster Gay Byrne. The book should find fans on these shores, too, as well-depicted friendship and seaside outings are hard to beat. An additional but nonessential purchase.

0 notes

Photo

Hats of the 1870s were more elaborately trimmed than hats of the 1860s.

In the early years of the decade, both bonnets and hats were often trimmed with ribbons at the back, which hung over the chignon, in addition to other trimming.

These disappeared in 1875.

After 1874, bonnets showed an increasing use of flowers in their trimming.

“Simple field blossoms are the most fashionable this summer,” said the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine in 1875, but almost any kind of flowers may be found on them.

The same journal commented in the following year that drooping foliage was worn, “a pleasant relief from the stiffness of the bonnets worn two years ago with high brim and formal flowers”.

Source: Vintage Dancer

Fashion plate with ladies’ hats, 1875.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cazaweck is for a morning dress, and is made of jaconet, trimmed all round with embroidery, and closed up the front with straps, which are also embroidered; two more narrower trimmings are placed round the basquine. Pagoda sleeves, embroidered same as the Cazaweck, are opened at small distances, and held by straps; the top of the sleeve is trimmed with narrower embroidery and small straps. The skirt of dress is embroidered and trimmed to match.

A cazaweck from The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, December 1855, p.288.

Not much news on what exactly a cazaweck is, save that they appear popular in the mid-century and a description from Graham's Magazine 1856 of 'a cazaweck is a long sack, reaching nearly to the knees, and fitting the body perfectly'. Considering the era, I would vouch it's a variant on 'cassock', perhaps influenced by the Ottoman fashions that were popular at the time - or perhaps Basque, going by that basquine.

#womenswear: morning dress#womenswear: cazaweck#womenswear: jackets#material: jaconet#material: embroidery#feature: pagoda sleeves#feature: basquine#journal: the englishwoman's domestic magazine#journal: graham's magazine#1855#1850s#1850s fashion#19th century#19th century fashion#womenswear

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Morning Cap we engrave is of embroidered muslin, trimmed with a ruche a la Vieille, with bows of ribbon intermixed in the border. The strings are embroidered muslin, rather wide and long.

A 'very pretty morning cap' from The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, December 1855, p.288.

#womenswear: morning cap#womenswear: caps#womenswear: headwear#womenswear: accessories#material: muslin#material: ruche#material: ribbons#1855#1850s#19th century#journal: the englishwoman's domestic magazine#source linked#id in alt text#19th century fashion#historical fashion#womenswear: morning dress#feature: ruche a la vieille#material: embroidery#womenswear

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The latest style of head-dress.'

The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, December 1855, p.288 (link in image source).

#journal: the englishwoman's domestic magazine#1850s#1850s fashion#historical fashion#19th century#1855#womenswear: headdress#headwear: headdress#womenswear: accessories#womenswear: hair#material: faux flowers#id in alt text#source linked#womenswear

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LILAC.

LILAC.—Archil, a root to be bought at the druggists. The colour, which is very powerful, is extracted in boiling.

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, May 1855, Collected Vol. 4, p.63. [x]

Scientific American (1853) notes these are largely cribbed from other publications, including the Baltimore Sun that year, and are incorrect, thus "will assuredly do evil". They correct thus:

ARCHIL—This substance will dye a lilac on silk; but not on cotton. It is not prepared as above—it is a litchen, and is steeped in urine and lime-water for a month before it is fit to be used. A patent was granted on the 15th of June, 1852, to Leon Jarossons, of this city, for manufacturing archil. The color which it makes is beautiful, but will only stand exposure to the sun a very short time—it is one of the fugitive colors.

“Receipts for Dyeing” in Scientific American Magazine Vol. 8 No. 48 (August 1853), p. 384 [x]

As a rule, I suggest you look for contemporary advice when attempting to recreate crafts from historical sources, and always utilise proper safety equipment and ventilation.

#1850s#1855#1853#journal: the englishwoman's domestic magazine#journal: scientific american magazine#journal: the baltimore sun#ingredient: archil lichen#ingredient: urine#colour: lilac#crafts: dyes#crafts#things worth knowing#corrections#ingredient: quicklime

0 notes

Text

YELLOW.

YELLOW.—Fustic chips, weld or dyer's weed, tumeric, or Dutch pink. GREEN may be produced by mixing the requisite portion of blue with either of the preceding.

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, May 1855, Collected Vol. 4, p.63. [x]

Scientific American (1853) notes these dye receipts are largely cribbed from other publications, including the Baltimore Sun that year, and are incorrect, thus "will assuredly do evil". They correct thus:

GREEN.—The fustic and blue spoken of above, will dye silk and wool, the former hot, the latter by boiling, the blue must be the sulphate of indigo. Yellow on cotton is dyed with the bichromate of potash, and the acetate, or nitrate of lead; or with yellow oak bark, and the sulpho-chloride of tin.

“Receipts for Dyeing” in Scientific American Magazine Vol. 8 No. 48 (August 1853), p. 384 [x]

As a rule, I suggest you look for contemporary advice when attempting to recreate natural dyes from historical sources, and always utilise proper safety equipment and ventilation.

It is quite obviously not safe to handle lead and other chemical products.

#1850s#1855#19th century#journal: the englishwoman's domestic magazine#corrections#journal: scientific american magazine#journal: the baltimore sun#sources linked#1853#crafts: dyes#crafts#things worth knowing#ingredient: fustic#ingredient: weld#ingredient: turmeric#ingredient: oak bark#colour: dutch pink#ingredient: iron(ii) sulphate#ingredient: potassium dichromate#ingredient: tin(ii) chloride#do not attempt without proper safety equipment

0 notes

Text

TO DESTROY COCKROACHES.

TO DESTROY COCKROACHES.—Cucumber-peelings are said to destroy cockroaches. Strew the floor in that part of the house most infested with the vermin with the green peel cut pretty thick. Try it for several nights, and it will not fail to rid the house of their not very agreeable presence.

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, May 1855, Collected Vol. 4, p.63. [x]

#1850s#1855#19th century#journal: the englishwoman's domestic magazine#untested#but seems unlikely#ingredient: cucumber#things worth knowing#housekeeping#housekeeping: pest control#housekeeping: cockroaches

0 notes

Text

FRECKLES.

FRECKLES.—The favourite cosmetic for removing freckles, in Paris, is an ounce of alum and an ounce of lemon-juice, in a pint of rose-water.

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, May 1855, Collected Vol. 4, p.63. [x]

Believe me - you don't need this or any other freckle remover. 1850s magazine writers don't know shit. Your freckles are perfect.

#1850s#1855#19th century#journal: the englishwoman's domestic magazine#the toilette#toilette: cosmetics#malady: freckles#ingredient: potassium alum#location: paris#allegedly#ingredient: lemon juice#incredient: lemons#ingredient: rose water

0 notes

Text

MILK OF ROSES

MILK OF ROSES is made thus: Put two ounces of rose-water, a teaspoonful of oil of almonds, and twelve drops of oil of tartar, into a bottle, and shake the whole till well mixed.

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, May 1855, Collected Vol. 4, p.63. [x]

Humblebee & Me offers a contemporary take on this recipe, which was still in use by the 1920s.

As a rule, I suggest you look for contemporary advice when attempting to recreate historical sources, and always utilise proper safety equipment and ventilation.

#1850s#1855#19th century#journal: the englishwoman's domestic magazine#the toilette#toilette: milk of roses#blog: humblebee & me#1920s#ingredient: rose water#ingredient: almond oil#ingredient: potassium bitartrate#toilette: cosmetics

0 notes