#imagining the forbidden five calling out their elements before using them like the Ninja used to

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

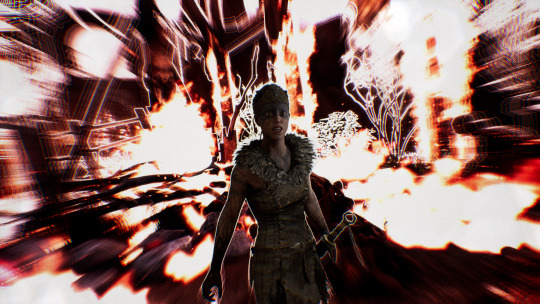

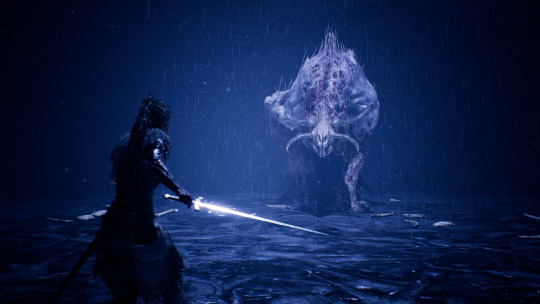

Hellblade's Language Problem

::WARNING: MANY HELLBLADE SPOILERS WITHIN::

I think I went into Hellblade with particularly well-balanced expectations. On the one hand, I had a vested interest in Ninja Theory’s success, having devoted several (rather grueling) years of my life to promoting their controversial last two titles, DmC Devil May Cry and its rerelease, DmC Devil May Cry: Definitive Edition as a community manager at Capcom. In my view, Ninja Theory greatly exceeded Capcom's and my own expectations for DmC, but they walked away from the experience dripping with rotten tomatoes from irate fans who wouldn't have been happy with any reboot of their beloved series, no matter what it did. With Hellblade, I'd wanted to see Ninja Theory get the credit I knew they'd long deserved.

On the other hand, I was also quite disappointed when NT revealed Hellblade to be a more narrative-driven piece, and I was downright worried when they still hadn’t highlighted the combat system after three or four PR beats. They were selling this game on its fancy performance capture technology and its treatment of mental psychosis, not its Smokin’ Slick Style and Just Guard mechanics. I’m fine with narrative-driven games, but there are tons of them nowadays, and NT is essentially the only Western developer to have sipped from Capcom's forbidden font of combat wisdom. NT walked away from DmC with a world-class mastery of combat design, honed under the direct tutelage of Capcom’s own Hideaki Itsuno (DMC series director and veteran fighting game dev) and his team of designers. It seemed a shame to let that mastery go underutilized.

I eventually concluded that Hellblade probably wouldn’t be the DmC-without-the-baggage follow-up I’d dreamed of, but it’d probably still excel on its own merits. In other words, I went in expecting a good game, but not expecting it to top DmC.

It pains me, then, to conclude that my experience with Hellblade was mostly just bad.

Early on in my time with Hellblade, I asked myself, “So is it ‘SEH-noo-ah’ or ‘SEN-yoo-ah’?” referring to the protagonist's name. Then one of the voices in Senua’s head called her “SEH-noo-ah.” A little later, one of the other characters calls her “SEN-yoo-ah.” Later still, Senua says her own name, pronouncing it "SEH-noo-ah." Much later, Senua’s own mother calls her “SEN-yoo-ah.” Is this inconsistent pronunciation a symptom of Senua's psychosis, or merely an oversight in the game’s voice direction? I don’t know, but I see it as symbolic of the overarching issue with Hellblade: it has a language problem.

When I say language, I’m talking about the visual, auditory, and tactile language that the game uses to guide its player. Ninja Theory took on a lofty challenge with Hellblade: to convey the experience of mental psychosis, using a video game. To be clear, psychosis is a severe mental disorder which presents the mind with vivid delusions—false sensory inputs. Video games, by definition, use sensory feedback—namely, graphics and sound—to communicate a consistent, predictable set of rules and parameters to a player. How do you simulate psychosis and make a functional game at the same time? How do you present meaningful feedback to the player while also inundating them with erroneous imagery and sound?

Ninja Theory actually found a variety of ways to do this. As they explain in the documentary included with the game, many sufferers of mental psychosis display a tendency to draw patterns and connections where none are apparent (to normoids). So essentially, they're ascribing their own rules and logic to the world. Arguably, this is what all game designers do anyway, so in that regard this premise might be surprisingly fertile ground. Indeed, we mostly see Senua’s hallucinations take recurring, systematic forms: glyphs which she must overlay with seemingly arbitrary sights in the environment; “portals” which, once passed through, reveal new avenues; and horrible humanoid demons, with whom Senua must do battle. Theoretically, these elements successfully convey Senua’s mental condition while still offering the player a “game” rather than just a series of crazy, unpredictable occurrences.

So what’s the problem?

The problem is a simple matter of execution; the game is technically flawed. Tutorial-less and HUD-less, it relies solely on subtle, in-world feedback to communicate its rules of engagement to the player, but then breaks those rules either through technical failure or conscious design choices. In a different game, I might have picked up on each bug or design issue much quicker, but because of the psychosis premise and the subtlety of the issues I faced, I found it abnormally difficult to distinguish between intended weirdness and simple video game flaws. In other words, the game isn’t just about being crazy—it is crazy.

Here are some examples:

-Early on, the game establishes that you can use the R2 button to “Focus” on certain objects in the environment to activate puzzles or audio logs. A little later, the game introduces a new type of "Focusable" object--an icon of a flame--but for some reason these objects don't respond to your Focus until you're much closer. The game betrays its established rule for how Focus works, without clearly reestablishing the new rule. I probably passed by that first flame icon five times, attempting to Focus each time but receiving no feedback. By the time I realized it was a distance issue, I’d wasted maybe thirty minutes searching for a way to progress.

-Focusing on each flame icon activates a sequence in which the environment is engulfed in an inferno, leaving you with mere seconds to run away before dying horribly. When I activated the first one, I instinctively started running in one direction, only to have the voices in Senua’s head started frantically crying, “No, not that way!” So I stopped and frantically searched for another path. Before I could find one, I died horribly. It seemed so unavoidable that for a moment I thought the death was scripted. When I realized it wasn’t and I respawned, I examined the surrounding area at my leisure and determined that, actually, there was no other path and I was running the right way. Was this a bug? Or was I now to understand that sometimes the voices in Senua’s head actively try to get her killed? I’ve since cleared the game and still don’t know….

-I encountered a bug which prevented one of the first puzzle-locked doors in the game from opening. It wasn’t totally clear that solving the puzzle was supposed to unlock that specific door, so I found myself wandering back and forth across the vast section of the map available to me at the time. Additionally, there were music cues which played upbeat, intense music within a specific radius (which didn’t even contain the door in question), and cut off abruptly the instant I stepped outside that radius. I scoured every inch again and again. After close to an hour of wandering and scouring, I googled it in exasperation and discovered it was simply a door bug. The music was just completely arbitrary. Unforgivable in a game that demands you take unexplainable sights and sounds at face value.

-One section of the game introduces a light/darkness mechanic. You must stand in the light at all times—either by carrying a torch or standing in designated illuminated areas—or you will die horribly within seconds. In one such instance, a fight sequence breaks out while you're carrying a torch. Senua subtly drops the torch on the ground as the fight begins, and a grueling battle ensues. When it ends, darkness floods your surroundings, and if you don’t think to retrieve the dropped torch, you die horribly within seconds. But what was illuminating us during the fight sequence, and why did it stop after I won? When the darkness came, my instinct was to run, which of course got me killed. I had to repeat the entire fight.

-The boss which follows the darkness segments has the ability to spew darkness (shoutout to DmC’s Hunter). Visually, this darkness looks just like the darkness which causes you to die horribly within seconds elsewhere, so the natural assumption is that you must scramble to find the light. This proved not to be true; rather, the darkness simply makes it dark, which sucks because it’s hard to see. Lol.

-The glyph puzzles, which I felt the game leaned on way too much, were extremely finicky. I often found myself desperately trying to line up the overlay with its apparent environmental counterpart, only to be denied feedback. “Guess I’m barking up the wrong tree,” I’d say, and search elsewhere. Eventually I’d circle back and retry for lack of any better ideas, and finally I would land upon the precise footing that triggered the game’s acknowledgement of my solution. Because of this finicky detection, it frequently took me upwards of thirty minutes to execute a solution I’d figured out in five. These moments deeply hurt the game’s immersion—it’s hard to believe someone tormented by voices and haunted by hellspawn would spend this long lining up glyphs with such surgical precision. I felt neither crazy nor like a warrior; I felt like a child with a defective issue of Highlights Magazine.

Weirdly, in other cases the game would give me credit just for glancing in the general direction of a solution I hadn’t actually noticed yet.

By the time the credits rolled, I’d experienced so many baffling inconsistencies in the game’s communication that the whole thing just felt like a misfire.

Now look--I’ve been known to both overthink things and not be very smart, so I don’t imagine everyone will have the experience I had. In fact, I googled “hellblade frustrating” just to see, and was shocked to find that all of the results were about how frustrating the combat was. I actually found the combat to be Hellblade’s saving grace—satisfying, consistent, and almost perfectly balanced thanks to a God Hand-style difficulty auto-balancing feature. The camera worked against me in a few situations, but most fights left me feeling like I’d beaten dire odds, and certainly made me sympathize more with Senua’s plight than the mundane action of lining up Viking runes with wooden scaffolding.

The moral of Hellblade’s tale seems to be that Senua won’t “cure” her psychosis, but that she can heal by learning to accept it as a part of who she is and coexisting with it. After finishing the game, it occurred to me that I would almost certainly have a better time with Hellblade on a second playthrough. Those bugs and flaws would still be there, but I’d know about them and be able to anticipate them. There’s an obvious parallel here. I don’t think it’s intentional (though the idea of “bad design by design” does intrigue me), but I think there’s some poetry in the notion that we can apply Hellblade’s lessons to itself.

All that aside, I appreciate what Ninja Theory has done to advance the conversation on mental health and develop a template for their "AAA indie" model. Hats off.

#hellblade#hell blade#ninja theory#games#gaming#gamming#video games#senua's sacrifice#playstation#ps4#senua#language#game design#design#mechanics#gameplay#reflections#review#god hand#dmc#devil may cry

3 notes

·

View notes