#i literally took time out of class to teach them about structuring paragraphs and essays and it was NOT a class about that at all

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

One of the summer classes I'm taking (not the videogame one) is soooo boring. Which is crazy bc it's about labor rights, something I'm genuinely interested in learning more about. But the way this class is structured has actually managed to make me not enjoy learning about it.

Because all the 'teacher' does is give us a list of sources, a prompt, & then says 'ok go write this essay'.

And he doesn't even give us open ended prompts either. He gives us a question but then also gives us the answer. Practically writes the whole essay & then says 'ok now go make these 2 paragraphs into 2 pages & cite the preapproved sources'

And he gives us outdated sources!!! I don't want to be using outdated data from 5 years ago to write about the 'current state of US employee benefits'!!! So then I look up the current data set for last year from the same index, use that to make an informed & up to date conclusion, & get told "you must base your papers more on the assigned readings" AND DOCKED POINTS

Nowhere in the instructions did it say we weren't allowed to do our own research & use outside sources.....

Another piece of feedback I got was "you don't need to list the full sources, just author and basic title" do you mean my fucking BIBLIOGRAPHY????? Or my in-text citations??? Why not????? Last I was told, it was good practice to cite your sources in an organized & comprehensive list, and to introduce them when you use them in the paper itself for the readers convenience & comprehension.

This class is contributing to the degradation of my mental state.

Now I understand people who say they hate school.....

When I took a similar class last semester during the school year, on the history of human rights, we had lectures where we were actually taught the information & then asked to write an essay based on primary sources & the lecture content (which we could cite in the paper & include in the bibliography)

The essays only took me 2 hours to write & were an absolute breeze. I loved that class.

And the reason why I'm not enjoying this class isn't just because the structure is optimized for teaching a semester's worth of content in one month online over the summer. Because the summer video game class that I'm taking at the same time (while being an absolute challenge, with all of the content we have to learn in such little time) is so much more enjoyable & structured completely differently. We get to watch & read content that actually teaches us stuff, quizzed on it, then asked to write a few paragraphs to prove that we can apply the concepts we just learned.

Literally what am I paying this other teacher for? Access to a compliation of out of date sources (that are mostly news articles anyway) and forcing me to regurgitate them in a paper? I could (and do) literally do that on my own time.

I can't believe I'm paying so much extra for thissss 😭 but I need the credits so I can't drop the class. Also I am learning things by reading what he gives us, I'm just not having fun doing it.

Rant over :P

#i wrote this to procrastinate on starting the readings to write my paper on farmworker rights in the US#its due tonight...

0 notes

Text

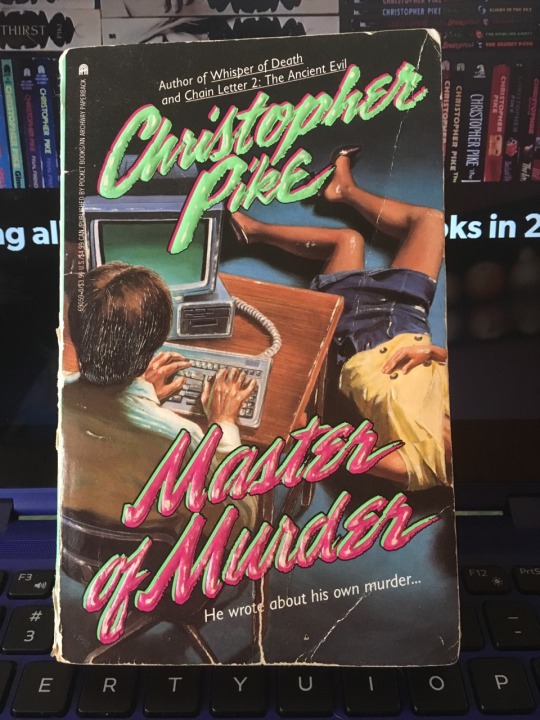

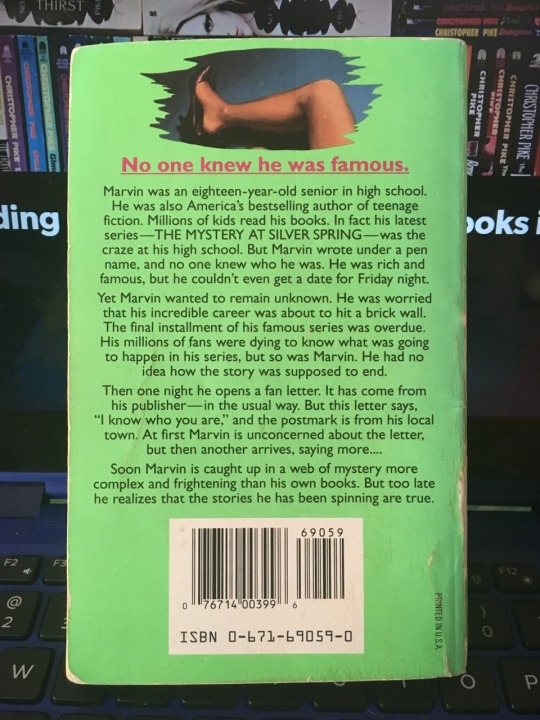

Master of Murder

Pocket Books, 1992 198 pages, 14 chapters + epilogue ISBN 0-671-69059-0 LOC: CPB Box no. 1081 vol. 14 OCLC: 26075926 Released July 28, 1992 (per B&N)

Everybody’s reading the thrilling Silver Lake series by Mack Slate. With the last book due out in a few months, fans are excited to finally find out who killed Ann McGaffer. Only problem is, Slate — that is to say, twelfth-grade nobody Marvin Summer, hiding behind a pen name — has no idea himself, and hasn’t even started writing the book. It’s only as he works to close the distance between himself and his crush, Shelly Quade, that the grand finale starts to make itself clear to him, in ways that unexpectedly and gruesomely parallel his own life.

This might not be my favorite Pike book, but it has certainly had the most influence on me. I’ve always called myself a writer, since a fifth-grade teacher recognized my ability to craft a narrative and pointed out that somebody had to make books and I should think about it. In high school, it was my defining trait, and it wasn’t until I’d almost graduated from college that I realized it didn’t make me special. Everybody has a story, as Marvin finds out, and some of them are even better at telling it in an engaging way. It’s sad, in a way, that I identified with this book so much (like, I literally carried it in my backpack for my entire senior year) and it still took me so long to get that theme.

What I did get was an intense sense of connection with Marvin. Shy loner? Check. Separated parents who didn’t get along? Check. Younger sibling who wanted to be like me? Check. An English teacher hung up on prescriptive strictures of language who quietly cared about her students, and a language teacher who was more interested in building a classroom community than sticking to a scheduled curriculum? Check and double-check. Writing ability revered by peers? Check, even if my work rarely made it past my immediate circle of friends. Subconscious inclusion of issues I was going through in my work, to the point where it got me in trouble with the girl I liked? Well, not directly observable, but I mean, it’s hard to not come off creepy if you’re writing a love story to a girl instead of, like, actually TALKING to her.

I also really enjoyed the way Pike works with language in this book, and honestly, I still do. Modern YA gets a lot more respect, and deservingly so, but a lot of it is written in a direct, almost sparse way. It makes sense, considering how many contemporary authors write in the first person, and most people don’t actually think in metaphors and syllogisms and even (to some degree) descriptive adjectives. Master of Murder kind of goes hog-wild on this, kind of a leap from representational art to impressionist art. And I buy it. As Marvin is our POV character, it makes sense that as a writer he’d put some more florid prose into his observations and understandings of the world. Plus, this style kind of helps to establish him as an unreliable narrator, as we slowly learn how much he actually doesn’t know and, in fact, how much maybe he’s repressed.

That said, this story does have some holes. Let’s jump into the summary and I’ll get there.

We start out with Marvin in his English class, watching Shelly read his most recent book and thinking about their relationship. They’d gone out a handful of times a year before, but it stopped after the death of Harry Paster, another flame of Shelly’s who’d jumped off a cliff into the nearby lake. Marvin figures enough time has passed that he can ask her out again, but first he has to read the short story he’s dashed off for their creative writing assignment. Man, remember when creative writing was an actual COMPONENT of high school English class? And the only reason I got to do it was that I took a creative-writing-focused senior English course. I mean, I get it — public school English is about preparing you to pass the SAT or ACT, not teaching you how to reach and grab an audience. They save that for us, in post-secondary ed, by which time the interest in writing has already been drilled out of kids by making them do repetitive five-paragraph essays. Most of my students still don’t want to write, but I at least try to give them some room in the assignment structure to flex their creative muscles.

But anyway, “The Becoming of Seymour the Frog” is a legitimately good short-short story. It gives us a sense of Marvin’s author voice straight away, which is of course the same as the narrative, and it legitimizes how much Pike uses what modern writers would call excessive description. The teacher grades it right away (what? I give everything two reads, and this teacher is just going to LISTEN one time?) and tells Marvin he might be a writer someday if he learns to control himself. We both (the reader and Marvin, that is) know he’s already there, and Marvin completely discredits this advice. He writes best by giving up control and going into a state of flow, one where he can’t stop writing but also doesn’t necessarily feel that what’s going onto the page is coming from inside his own head. This is important later.

After class, he catches up to Shelly, but their talking is interrupted by the arrival of her current squeeze, Triad Tyler. Triad is a big dumb football jock who wants to buy Marvin’s motorcycle, which Marvin would never dream of selling. Before he can get around to asking her out, she ducks into the bathroom, and Triad complains that it seems like she’s always trying to escape. This is probably important later too. So already in the first 15 pages, Pike has nicely set up the major characters and their interplay with each other.

We jump to speech class, and I call BS. Like, we learn later that Marvin only has four classes as a senior. Why is one of them speech? My high school only required a half-day of seniors, sure, but our classes were English, math, world history, and economics. It turns out this class would be better called “communication skills,” which was required in ninth grade, but I’d still buy that more than speech. The teacher basically has them engage in conversational debate, and this day the topic they choose is Mack Slate’s Silver Lake series. It’s a good framework for sharing Marvin’s story, and showing the corner he’s painted himself into: Ann McGaffer’s body was found naked and tied up with barbed wire floating in Silver Lake, and five books on we’re no closer to figuring out who did it or why. The description grosses me out a iittle bit, but on the heels of the last two super-tropey thrillers, I’m going to choose to believe that Pike is poking fun at the intentional shock attempts of the genre.

After class, Marvin finally successfully asks Shelly out for that night, then goes to his PO box to pick up his fan mail. His little sister is already there, and once again we’re subjected to the jaw-droppingly beautiful small child. It was gross when it was fifteen-year-old Jennifer Wagner, but Ann Summer is ELEVEN and Marvin’s SISTER. Pike, isn’t it possible to describe a female one cares about without making it all about her looks? He does it with Marvin’s mom in a few pages too, when they get home. We get it — girls we care about are hot. Only problem is Marvin’s mom is an alcoholic who almost never leaves the house except to buy more booze. Dad is an alcoholic, too, but he’s not at home and his child support payments are erratic. Good thing there’s a best-selling author living in the house! But Ann’s the only one who knows, and it kills her to not be able to sing her brother’s praises and brag about how great he is.

They go upstairs to Marvin’s room to read his mail, and one of the last letters makes him pause. It has a local postmark, and the letter inside simply says “I KNOW WHO YOU ARE.” It starts to pull the book into more general thriller territory, but before we can think too much about it, the phone rings and it’s Marvin’s editor, asking about Silver Lake Book Six, which is four months overdue. I have some serious questions about the timeline of this series, but we’ll get there in a little bit. Marvin soothes her concerns, then goes to take a walk around the lake, trying to figure out where to start his book but not actually ready to start it before he picks up Shelly.

The date is successful, by most measures. They have dinner, go to a movie, and then stop on a bridge crossing a raging river because Shelly wants to look at the water. They sit down on the edge, Marvin landing on an old and weathered piece of rope, and watch the waters pound away down to their final destination — the lake. Then Shelly invites Marvin back to her house to sit in the hot tub, where they get naked and make out, but she suddenly gets sad and pulls away. I give Marvin props for being respectful and apologetic here rather than trying to force her to continue. Woke in 1992! But as he’s getting ready to leave, he learns the reason she’s sad: Shelly is thinking about Harry, which he expected, but he didn’t expect to learn that she thinks he was murdered. And she wants Marvin’s help to figure it out and clear Harry’s name.

There’s no basis for this belief, but Marvin figures he might as well listen and do some research, seeing as he can’t figure out his own murder mystery. He checks his PO box first, and finds another ominous letter that’s been mailed there directly rather than to his publishing house, so maybe somebody really does know him. He calls his agent (whose name is one letter away from a real literary rep, maybe even Pike’s) to ask about it. This insert, plus the editor whose name was close to the woman in charge of YA at Simon and Schuster at the time, made so many of us so sure that this was as close to autobiographical as Pike had ever gotten. I seriously chased leads from this book to try to figure out more about him, back before he started answering questions on Facebook and there was so much less mystery about it.

So then Marvin goes back over to Shelly’s house to talk about Harry. She has the police report and autopsy report, and Marvin looks them over, along with articles about Harry’s death from newspapers at the time. What it boils down to is Friday night a year before, a night when Marvin had taken Shelly out for her birthday, Harry and Triad were drinking beer together. Triad said that he dropped Harry off at home, and that was the last time anybody saw him until a fisherman found his body in the lake on Monday morning. Marvin starts to question the narrative that Harry jumped, because there are several physical symptoms that indicate maybe he was held captive. He talks to the fisherman and to Harry’s mom, and takes a look at the jacket Harry was wearing, and makes note of definite rope burn marks around the back and under the armpits. So Harry was tied up somewhere for a long time — but where? And how?

Marvin goes home to rest and digest this info, and has a dream about his book series that shows Ann McGaffer hanging from a bridge by a rope around her waist. He’s startled awake by Ann, who says that their dad is breaking things downstairs. Marvin gets down there just in time to watch his dad shove a lamp into the TV, and the resultant cuts to Ann and his mom from the exploding picture tube send Marvin into a fit of rage. He starts to beat the shit out of his own father, and only stops when Ann tells him to, even though the dude is unconscious. Like, holy shit, buried violent tendencies that will make you like your father? So Marvin gets the hell out of the house to give himself some space.

He ends up back at his PO box, even though he knows there couldn’t have been another delivery, but there sure is a letter in it. He follows this back to Shelly’s house, where he finds her making out in the hot tub with Triad. Marvin overhears her say that she was using him to get him to do something, and Triad tells her not to go out with Marvin anymore, to which she readily agrees. So now Marvin is scared, he is heartbroken, and he has unlocked some deep-seated rage that will allow him to strike back. He ends up on the bridge, where he starts to figure out what must have happened a year ago. There’s a rope, there’s a giant oil stain on the bridge right behind it, and there’s a dead boy with rope burns on his jacket who was maybe hanging from it rather than being tied up. Marvin figures that Harry was jealous of his relationship with Shelly and decided to stage a little motorcycle accident, but accidentally slipped off the bridge and ended up hanging himself, slowly suffocating to death until the rope broke and he washed down to the lake.

And it occurs to Marvin that this would be a perfect way to get back at Triad.

After a misadventure with two girls in a bookstore who accuse him of trying to pick them up by pretending to be Mack Slate, Marvin buys a new car and a bunch of motorcycle-dropping gear at Sears, then takes the bike to Triad’s house to sell it to him. Marvin says that he left the helmet in a motel in the town across the river, and that the manager said he was going to throw it out if Triad didn’t pick it up tonight. Then he hikes to the car, which he’s had delivered around the block, and goes to stake out the bridge. While he’s waiting, he starts to think about the parallels between his own series and how Harry died. And we learn that the first Silver Lake book only came out after Harry’s death — in fact, that Marvin didn’t start writing it until then.

So this is my timing issue. Master of Murder does have some gaping inconsistencies, I’m not gonna lie. There’s the variable height of the bridge over the river: it’s 150 feet when Marvin and Shelly stop on their date, and maybe 60 when they have the final showdown two nights later. Also, later apparently Shelly knows details of a book that Marvin hasn’t even written yet? But this, in my mind, is the biggest problem. We’re supposed to believe that in a year, five books have come out about Ann McGaffer and her loves and hates. We’re also supposed to believe that he’s four months late with book six, and that it takes at least three months for the publisher to turn a story around and get it into bookstores. We also have the information that the fastest Marvin’s ever written a novel is eighteen days. So by that logic, there’s no way he could have finished and submitted Silver Lake Book One before mid-December. So five books have somehow appeared between probably March and let’s say November (they say the fifth one just came out) — five books in seven months — but they’re going to wait another three months to release the sixth? Also, how does an author, even an experienced and acclaimed one, sell a six-book series to his publisher without knowing the beats and especially the ending? There are too many inconsistencies and timeline impossibilities for me to buy it. If I didn’t know better, I’d say Pike was a new author writing publication fanfiction.

But anyway, Triad races across to the other town. Marvin is too far away to see him, but he recognizes the sound of his motorcycle. He grabs his rope, his knife, his can of oil, and his binoculars, and hustles the probably mile to the bridge to set up his death trap. But as the motorcycle is coming back, he gets his first good look — and sees Shelly on the back. So he drops the rope, but Triad is already braking, stops short of it, and shoves Marvin off the bridge.

So now it’s Marvin hanging from his armpits by a rope under the bridge above a raging river that leads to the lake in his town, and did I mention he’s wearing Harry’s jacket? Shelly’s more annoyed than angry — it turns out she’s expected this from Marvin the whole time. In fact, she DOES know who Mack Slate is, and she’s already read about this scheme in the Silver Lake books. But Marvin doesn’t even remember writing it. She wants to turn Marvin in to the police. But Triad wants to untie the rope and drop him into the river.

And suddenly Marvin knows what actually happened. Harry wasn’t alone on the bridge a year ago. Triad was with him, and shoved Harry just as he shoved Marvin. Shelly doesn’t believe it until Triad knocks her out for trying to stop him killing Marvin too. Marvin manages to get hold of the underside of the bridge just as Triad unties the rope, then he kicks Triad in the face when he leans over to look and see whether Marvin has actually fallen. The semi-conscious wedged body of the football jock gives Marvin a ladder to climb back up onto the bridge, and he stomps out Triad’s bad knee when the dude wakes up and threatens to go after him again. Only the knife falls out of his pocket as he does so, and Shelly picks that moment to come to, and it’s a simple matter for Triad to grab both her and the knife and threaten her death if Marvin doesn’t help him get away.

What’s in it for Marvin, though? The guy who tried to kill him is holding the girl who tried to frame him for a death the guy is responsible for. He gets on his bike, where Triad has courteously left the keys in the ignition, and drives away. I don’t like that he’s left a vulnerable girl at the almost-complete mercy (he can’t stand up) of a confirmed killer. What I like least is that he doesn’t even call the police. But then again, he’s abandoned his new car in the woods near the scene and surely doesn’t want to be implicated if somebody dies. So Marvin drives to a seaside town, rents a house and a computer, and writes an entire book in five days, only stopping to eat and sleep. Of course, within a few pages of the end he has to stop, because he doesn’t actually know how Ann’s best friend, left in the clutches of the boyfriend’s jealous best friend, is going to escape, or whether in fact she does.

Marvin calls his editor and tells her the story is done and he’ll express-overnight it to her. He also asks her to set up a reading from it at his high school that afternoon. More BS? Like, how are they going to allow an author to read from a book that the editor hasn’t even SEEN, let alone put through proofs and galleys? Marvin has to physically print and ship the manuscript — remember, this is 1992 and most people don’t have email yet (and when it would become widespread in a few years, it still had a hyphen). But she does it, and Marvin goes home first to find out that Dad’s in jail and Mom hasn’t touched a drop since. More good news! He takes Ann with him to school, where the entire student body is in stunned disbelief about the identity of Mack Slate, and finally gets some personal acknowledgement from his peers and teachers.

But Shelly doesn’t show up. Neither does Triad. The kids he does ask say neither has been in school all week. Marvin can’t dwell on this, because he has a major book series to finish, but it’s precisely this reason that he hasn’t made it all the way to the end yet. He knows that he needs someone else’s story to finish his own. So he goes back to the lake, and makes his way to the top of the cliff that everyone thought Harry jumped from. As he’s thinking, Shelly shows up with his knife. She tells Marvin that she suspected him of being Mack Slate back when they were dating, and he would tell her stories that had the same voice as Slate’s published work. So she sneaked into Marvin’s room one day and snooped in his computer for proof.

When the Silver Lake books started coming out, she saw the parallels immediately, and figured the only way Marvin could have known so much about how Harry died is if he had killed him. She got Triad, Harry’s best friend, to help her set up a situation where Marvin would implicate himself, not realizing that Triad had always wanted Shelly and been jealous of both of the other guys and didn’t care who hurt if it meant nobody else could have Shelly. That includes Shelly herself: if Triad couldn’t be with her, nobody else would. He didn’t tell Harry that Marvin and Shelly were out together that night, and when Harry realized Shelly was on the back of the motorcycle he did like Marvin and dropped the rope. So Triad pushed him.

Triad obviously has told Shelly all of this, and Marvin figures the only way he would have is if Shelly somehow overpowered him. It’s an interesting twist that she told Triad about using Marvin to get him to figure out Harry’s death and Triad never realized she might use him for the same purpose. (I feel like Shelly has more strength than even the story gives her credit for, seeing as Pike describes all her agency as coming at the hands of her feminine wiles.) Marvin suspects that here, the spot where it all began, is the spot where it has all ended as well, and that the soft soil where he’s sitting is Triad’s final resting place. Shelly doesn’t say as much, but elicits Marvin’s silence before throwing the knife into the lake. But of course Marvin still has a book to finish, and Shelly’s OK with that as she’s apparently the only one who’s figured out the parallels anyway. The book closes with them in Marvin’s car, Shelly driving to Portland so they can get the manuscript on a flight to New York while Marvin writes the last few pages longhand.

I have to admit it: I still really like Master of Murder. Obviously I’m not in high school anymore, so I don’t relate to Marvin the way I used to, but I do connect to his being trapped in his own story and having to listen for others. The book has a lot of holes and inconsistencies in general that either I didn’t notice when I was a teenager or I glossed over in the excitement of having a character I could relate to so well. In particular, the YA publishing description is not without issues, and the ways the industry has changed after the Internet and Columbine and social networks and Trayvon Martin and #MeToo don’t jibe with the already-shoddy impression of how it works that Pike puts on display. The story is consigned to be a relic of its time. But for those of us who were there, who were trying to make our stories heard the way Marvin wanted to, it carries some warm nostalgia. Maybe I only like it so much now because I liked it then, but I’m OK with that.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is the Five-Paragraph Essay Dead?

Dennis Allen doesn’t think the five-paragraph essay is dead.

In the years before his retirement in May from West Virginia University, the Professor Emeritus did not assign “strict” five-paragraph essays. He contends that the five-paragraph essay may be dead in the literal sense because instructors of college composition classes don’t assign it, but he believes its structure is still around.

“I think a dissertation chapter is just a substantially more elaborate version of this,” Allen, who taught at West Virginia University for 35 years, explains. “In other words, the first five pages are the introduction with a thesis near the end, and you have two to five points, and it just expands out.”

The five-paragraph essay is a topic long debated by educators, and strong opinions abound. Ray Salazar called the five-paragraph essay an “outdated writing tradition” that “must end” in a 2012 post for his blog White Rhino. And in a 2016 blog post for the National Council of Teachers of English, Sacramento State associate professor Kim Zarins used the five-paragraph essay structure to show why she’s against teaching it. She called herself a high school “survivor of this form.” Despite its “long tradition, the five-paragraph essay is fatally flawed,” she wrote. “It cheapens a student’s thesis, essay flow and structure, and voice.”

A year later, her stance hasn’t budged.

“When I see five-paragraph essays come into the stack of papers, they invariably have this structural problem where the ceiling is so low, they don’t have time to develop a real thesis and a truly satisfying or convincing argument,” she says.

Five-paragraph essays are not the majority of what Zarins sees, but she points out that she teaches medieval literature, not composition. Regardless, she thinks high school teachers should steer clear of this approach, and instead encourage “students to give their essays the right shape for the thought that each student has.”

Kristy Olin teaches English to seniors at Robert E. Lee High School in Baytown, Texas. She says sometimes educators have structures that don’t allow for ideas, content or development to be flexible, and instead of focusing on what’s actually being said, they become more about “the formula.”

“It seems very archaic, and in some ways it doesn’t really exemplify a natural flow,” Olin says about the five-paragraph essay. “It doesn’t exemplify how we talk, how we write or how most essays you read are actually structured.”

Consider paragraphs. They should be about one subject and then naturally shift when that subject changes, Olin explains. But because the five-paragraph essay structure dictates that there be three body paragraphs, students might try to “push everything” to those body paragraphs.

Olin does think, however, that the five-paragraph essay format is useful for elementary students, adding that fourth grade is when the state of Texas starts assessing students’ writing in standardized tests. But once students get into sixth, seventh and eighth grade, teachers need to break away from that five-paragraph essay format and say “‘this is where we started, and this is where we need to head.’”

Hogan Hayes, who teaches first year composition at Sacramento State, is the second author of an upcoming book chapter about the “myth” that the five-paragraph essay will help students in the future.” There’s a perception that if students get good at the five-paragraph essay format, they’ll hone those skills and will be good writers in other classes and writing situations, he says. But there’s “overwhelming evidence to suggest that’s not the case.”

He doesn’t think that first first year composition teachers should be spending time “hating the five-paragraph essay.” Instead, they should recognize it as knowledge students are bringing with them to the classroom, and then “reconfigure it to new contexts” and use it ways that are more college-appropriate.

Hayes says college writing instructors need to get students to understand that the reason their K-12 teachers kept assigning five-paragraph essays was because they were working with “100, 120, 150 students,” and a standardized writing assignment “that works the same way every time” is easier to read, assess and grade. In regards to students who leave K-12 with a “strong ability to write the five-paragraph essay,” he says, ““I don’t want to snap them out of it because I don’t want to dismiss that knowledge.”

Take McKenzie Spehar, a Writing and Rhetoric Studies major at the University of Utah. She says she learned the five-paragraph essay early on, and except in an AP English class she took in the 12th grade, the structure was pushed heavily on her at school. She can’t say she’s ever written a five-paragraph essay for college. Her papers have all needed to be longer, though she does note that they do tend to stick to a five-paragraph type format—an introduction, a body and a conclusion.

“In general, the consensus is you need more space than a five-paragraph essay gives you,” she says, adding that it’s a good place to start when learning how to write academically. She explains that later on, however, students need a looser structure that flows more with the way they’re thinking, especially if they go into the humanities.

Kimberly Campbell, an Associate Professor and Chair of Teacher Education at the Lewis & Clark Graduate School of Education and Counseling, is strongly opposed to the five-paragraph essay structure. She thinks it stifles creativity and “takes away the thinking process that is key for good writing.” And she says she’s not the only one worried that the structure doesn’t help students develop their writing. In Beyond the Five-Paragraph Essay, a book she wrote with Kristi Latimer (who teaches English Language Arts at Tigard High School in Oregon), Campbell cites research studies that critique the approach of teaching the five-paragraph essay.

“Studies show that students who learn this formula do not develop the thinking skills needed to develop their own organizational choices as writers,” she says. “In fact, it is often used with students who have been labeled as struggling. Rather than supporting these students, or younger students, it does the opposite.”

For his part, Hayes thinks the five-paragraph essay makes it easy to not be creative, not that it necessarily stifles creativity. He believes creative students can work their imagination into any structure.

Allen, the retired English professor, stresses that even if writing isn’t argumentative, it always needs some structure. It can’t be simply uncontrolled, because the reader’s not going to get the point if it’s all over the map.”

Rita Platt is currently a teacher librarian with classes fromPre-K to fourth grade at St. Croix Falls Elementary School in St. Croix Falls, Wisconsin. She still stands by a piece she wrote in 2014; in it she said she was “being really brave” by stating she believes in teaching elementary school students “the good old fashioned” five-paragraph essay format.

She thinks the five-paragraph essay format has room for creativity, such as through word choice, topic and progression of thought. Kids can use the five-paragraph essay model to organize their thoughts, she says, and once they’re really comfortable, they can play around with it.

“Kids need something to start with,” says Platt, who has 22 years of teaching experience across different grade levels.

Campbell’s recommendation, which she says research backs, is to focus on reading good essay examples and give students in-class support while they write. She wants students to read a variety of essays, and pay close attention to structure. The students can then develop ideas in a writing workshop. As they develop their content, they consider how to structure those ideas.

“Students can explore a variety of organizational structures to determine what best supports the message of their essay,” Campbell says.

Platt tells EdSurge that she thinks there’s a movement in writing that says to “just let kids write from the heart.” But that means the kids who aren’t natural writers are left “in the dust.” What’s more, this approach doesn’t honor the constraints of teachers’ jobs, such as how much time they have to teach. And not all teachers love writing or write themselves, she says. Many elementary school teachers, she claims, never write, and not everyone has the skills of, say, Lucy Calkins or Nancy Atwell.

Campbell’s not a fan of asking kids to “‘just write from the heart.’” She wants kids to write about topics they care about, but at the same time, recognizes that instructors do need to teach writing. She says her mentor text method described above “is a lot of work,” but it was effective when she taught middle school and high school.

“In my work with graduate students who are learning to be English Language Arts teachers, I am also seeing this approach work,” she explains. She adds that her method would be easier if class sizes were smaller and teachers weren’t trying to “meet the needs of 150-200 students in a year.”

Most people aren’t going to become professional writers, Platt continues, noting that she’s not saying most people couldn’t, or that schools shouldn’t encourage people to think that way. She says there’s a sense of elitism in education that she gets a little tired of, along with some teacher bashing that makes her feel like she has to defend her colleagues who aren’t themselves natural writers yet are tasked with teaching kids to be “serviceable writers.”

“It bothers me in education—particularly in my field, language arts—where everybody says, ‘everybody should love reading and writing,’” she says. “Well, you know, you hope everybody loves reading and writing. You model that passion, you share that passion with your students but truth be told, our job is to make sure everybody reads and writes very well.”

Is the Five-Paragraph Essay Dead? published first on http://ift.tt/2x05DG9

0 notes