#i hadn't previously seen him using this overwhelmingly bad sources

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

My favourite podcast Behind the Bastards unfortunately made a two-parter of Beau Brummel. Unfortunately because while the host Robert Evans is usually very good at researching history even though he is not a historian but a journalist, he has in previous episodes misunderstood dress history in very typical ways. I don't really blame him, since most historians not specialized in dress history also make these very basic mistakes, but for personal reasons (ADHD) it's just intolerable to me. The name of the episode is "Beau Brummell: The First Celebrity and Inventor of the Suit and Tie" so I was immediately assuming the worst takes. Then I checked the sources and it's bad guys, it's real bad.

Beau Brummell was a 19th-century fashion icon for men (archive.is) "Beau" Brummell, the Dandy Who Invented Men’s Suits (aristocracy.london) Beau Brummell Wasn’t a Hero of Modern Men’s Fashion. He Was a Villain. A Boring, Uptight Villain. (esquire.com) https://reginajeffers.blog/2022/07/18/purchasing-commissions-during-the-napoleonic-wars/ A Revolution in Masculine Style: How Beau Brummell Changed Jane Austen’s World » JASNA Beau Brummell: The Most Stylish History Maker – Never Was (neverwasmag.com) Man of the Cloth - The New York Times (nytimes.com) Blog | Regency History https://www.amazon.com/dp/1416584587?psc=1&language=en_US

So all but one are magazine articles or blog posts. The only book is by a fiction and biography writer, who is not a historian, definitely not a dress historian. The only writer of any of these sources that has any related credentials is one of the writers of that JASNA article and he is an art historian specialized in Byzantium, he's other specialty seems to be Jane Austen. In addition that esquire article is one of the worst perpetrators of these Beau Brummel myths. It's so disappointing because while his sources are not usually academic level, they are usually of good quality and he does usually practice critical assessment of his sources. Like I just wish people would cite actual dress historians in these matters and not random historians who actually know nothing about dress history because it's such an underappreciated field even inside academia. Or worse the god damn esquire or random blogs.

Obviously I can't listen to the episodes because three hours of dress history misinformation might just kill me. I will entertain a slight change I'm wrong about the episode, but where would he get high quality info if all his sources are garbage? So I'm reblogging this post now to even slightly balance the misinformation that will now spread even further to new audiences.

This just might be my 9/11.

https://www.tumblr.com/thebaconsandwichofregret/189924928150/comepraisetheinfanta-thebaconsandwichofregret

whenever i see people rbing the op without the additions i die a little inside so i thought you should have a go at debunking it 🫠

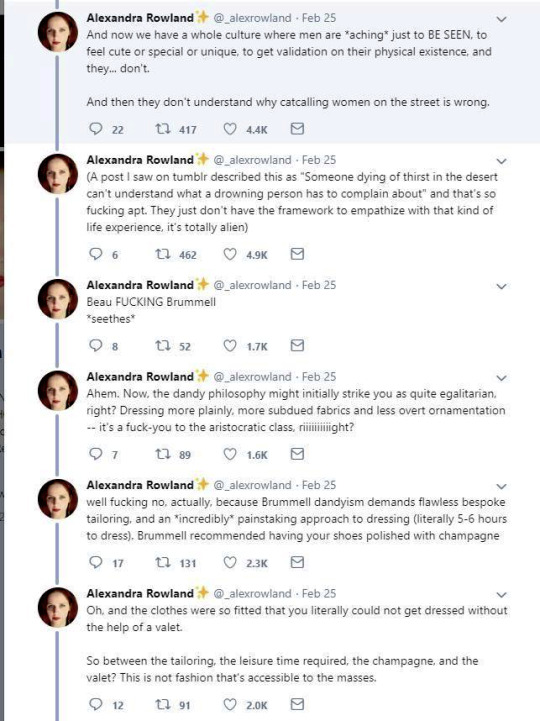

So these are the tweets from the post. I had blissfully not come across it before. This is one of the weirdest takes I have ever seen. It's amazing to see these fashion history takes that are so boldly and confidently wrong and inaccurate.

It's honestly hilariously ignorant to think that a massive cultural and societal shift that took couple of centuries was all because of one guy. It's so reductive and even goes to the great man territory to pick one person to blame for something like this that really had much more broad and complex reasons than "a guy did it". It's stressed in this tread that Beau Brummell was not noble or gentry and "just some guy", so how would he single-handedly change the fashions and concept of masculinity of the whole western world? He was a London socialite, it's not like most of his contemporaries in continental Europe knew about him. Like maybe the French, but does anyone really believe people in Eastern-Europe or Nordic countries or the Mediterranean knew about? Not to mention places like US. Yet everyone dressed like that in his lifetime, so how could his influence reach so far so quickly? Not even kings and queens could so directly and massively shift the fashions. So in the face of it the whole claim is ridiculous, but it's also full of inaccuracies.

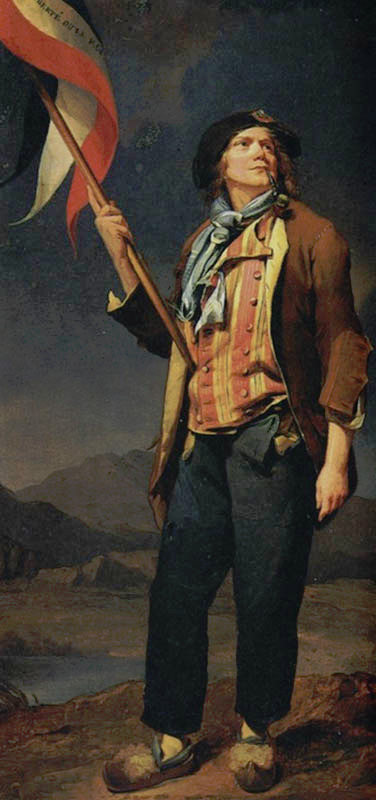

The shift from Rococo fashion to regency fashion was extremely stark and quick in both men and women's fashion, but it happened during 1780s and 1790s, before Beau Brummell became a well known figure in the London society (he was born in 1778 and became well-known in the society after his military career, during which he befriended the Prince of Wales, around the end of 1790s). Here's first an example from 1780s and then from 1793-94 and 1797.

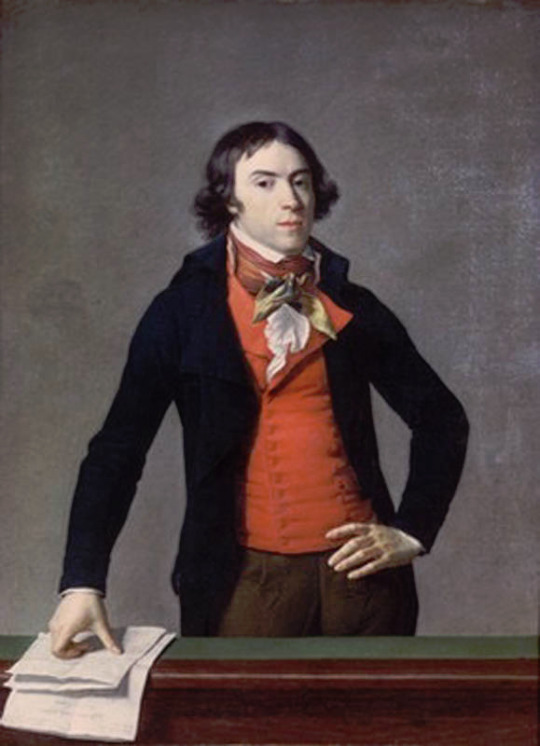

The one from 1780s still has some Rococo elements like the wig, but it's already much more toned down and the coat is already turning from frock coat to a tail coat. It's an example of the more casual men's countryside dress from the period. The court dress was still quite elaborate, though also toned down from the 1770s. But there's a big shift when it comes to the examples from 1790s. They are unmistakably Regency fashion. All of these example are French too. I'm sure these people had no idea and gained no influence from an unknown middle class English officer. So what did actually happen? Well, I'm pretty sure the French Revolution in 1789 had a little bigger impact on the European society and fashion than Beau Brummell.

I'm not going to go too deep into this, since I'm working on an in depth post about the masculinity and fashion in the modern era and I go into detail about how the French Revolution had a massive part in shaping them. But the short version is that the French revolutionaries rejected the elaborate fashions of the Rococo French nobility (in both men and women's fashion) as those over the top fashions stood as symbols of the excess wealth of the nobility and the extreme wealth gap. This is also why the high fashion was getting toned down thorough the 1780s before the Revolution. The anger towards the ruling class was mounting at the time and it encouraged the nobility to try to act a little more palatable in their aesthetics to maybe appease the angry people without doing any actual change to address the wealth gap and the centralization of power.

The revolutionaries looked for ideal masculinity and femininity elsewhere then. To contrast themselves against the ruling class, they looked to the antiquity and it's simplicity as well as the peasantry and the country gentleman fashion. Romanticism was the driving force behind the artistic expression of the Revolution. It weaved nationalism to the class struggle that was at the core of the revolutionary movement. So the Revolution was not just the working class and peasantry against the ruling class, but the French People against the nobility. That's how the bourgeois was able to align themselves with the working class and peasants. This is when physical labour, militarism, dominance and leadership really became intrinsically attached to masculinity, as the ideal man of the revolutionaries was a working peasant, who with military might took the the power back to the people from the nobility. The democracy would not last long, but it's not a mistake that only men could vote under the new democracy after the Revolution was won. It's also not a mistake that even when the post-Revolution France eventually abolished slavery (but not without some push-back first and a couple of slave revolts to force their hands) they didn't give most people of color rights to vote. Since colonialism whiteness had become intrinsic part of masculinity and femininity to dehumanize everyone else, and the new form of masculinity and femininity born out of the Revolution did not contest that. In fact the Enlightenment philosophy that had laid the ground work for the Revolution and the Romantic movement and it's nationalism that were driving force in it, in no way contested colonialism or it's white supremacy. In fact Enlightenment aimed to rationalize those things. Which is why the power in the new democracy went to the (mostly) white men.

These elements were in the new men's fashion too. Nationalism, the idealization of militarism, romanticization of peasantry and antiquity were basis of the fashion. Because antiquity was seen as the origins of democracy and the so called Western Civilization, that made it, and especially Antique Rome with it's militaristic connotations, perfect inspiration for the Revolutionary France. The short hairstyle was inspired from the Roman fashion seen in statues. The fashionable tail coat was influenced by military uniforms and the short jackets of the working class. The long trousers also came from working class dress. Here's examples of the revolutionary fashion of commoners, first from 1792 and then around 1790.

To be very clear, the revolutionaries were not a single entity with single ideology. They were collection of movements, who were united in their shared desire to overthrow the ruling class and establish some sort of democracy. But inside the movement were much more radical factions than what eventually ended in power after the French nobility. Socialists, abolitionists, feminists, slaves and others also fought for the Revolution and there was a lot of internal struggle too. Romantic movement was also very varied and contained extremely nationalistic elements as well as outright socialist elements.

It's important to note that the 18th century Rococo fashion was never as extreme elsewhere in the world as it was in France, so the change from Rococo to Regency style wasn't as stark elsewhere. If you put the most elaborate French court fashions of mid 1700s and Beau Brummell's style next to each other the difference is certainly massive, but fashion for men as well as women was through 18th century much more restrained and somber in England. Here's an English example from 1755-65 and for comparison a French example from 1755.

In fact as the tensions were rising in France the upper class begun to adopt the more toned down English styles. After the Revolution the new Republican styles would spread to Britain too. In Britain though Romanticism had a more pronounced effect as it stayed firmly monarchist. Therefore the English fashion was especially influenced by the styles worn by country side gentlemen.

There's another claim in the thread that fully fails to understand the broad implications of fashion and societal gender and how these things change and evolve. It's the claim that Beau Brummell created the modern men's suit and he's the reason the suit has long trousers. We already went through how long trousers initially got into men's fashion and it was not him. But the writer is not wrong in saying that Beau Brummell's outfit in this picture is a direct ancestor of modern men's suit. It is.

But you know what else is a direct ancestor of men's suit? This.

The modern three piece suit has it roots as far as in late 17th century. Before suit men wore doublets, hose and jerkins, where the sleeveless piece, jerkin, was on top of doublet. Aside from hose, these were also items women used and the fashions for men and women resembled in style and construction each other much closer than after the suit took over (as seen in these examples from 1630s). However the distinction between men and women's fashion had started to grow much earlier. A big shift that happened during the 16th century was that men stopped wearing skirts. Men and women wore the same garments for centuries before that. The styles and silhouettes for men and women had some differences (the skirts were often shorter for men for example) but they were parallel to each other. I wrote a whole very long post about how skirts stopped being acceptable for men. In it I write about how the shift in men's fashion was part of the large shift from feudalism to colonialism and capitalism, that needed a new hierarchy to justify the new system after the previous divinely justified feudal hierarchy was no longer an option. The new hierarchy was white supremacist patriarchy and therefore needed a clearer distinction between white men and white woman, that would also help distinct white people from the racialized people.

But such fundamental changes in the societal structure and culture are long processes. The process was continuing in the latter half of the 17th century, when Orientalism first became very popular. Orientalism is the dehumanization and fetishization of Asia and North-Africa, and it was born as the European colonial project was properly getting going in Asia. Colonialism in Asia and North-Africa took a little different form. I suspect it was because it was not that long ago, when Europeans had felt inferior to many of the peoples and empires in Asia and North-Africa, which they had always had much closer relationships with than the rest of Africa and certainly the Americas. I think that's why Orientalism is such a mix of coveting Asian and North-African cultures and bodies in a very fetishistic ways, while also demeaning and diminishing them. Nevertheless, Orientalism had a huge impact on European fashion in late 17th century. Both the way men and women's clothing was made after that to this day was strongly impacted by Orientalism. The coat and waistcoat combination was an adaptation of Turkish fashion. The three piece suit became popular in 1670s and fully took over men's fashion in 1680s (an example from 1687). The cravat was also adopted around the same time to men's wear from a light cavalry mercenary army in the Habsburgian Empire known as the Croats or Cravats. They were mainly Croatian, which to Western European was almost "Oriental" due to their proximity to Asia and Turkey in particular, and therefore the popularization of cravats as a fashion item was also influenced by Orientalism. Orientalist fashion encompasses the paradoxical nature of Orientalism itself; the Europeans coveted "the Orient" so they bastardized their fashions to construct a gender binary that left out the people who originated those fashions.

The Regency three piece suit also has all the same elements as the suit 150 years earlier, the individual pieces had just evolved into different cuts and silhouettes. The construction and the basic elements have stayed pretty similar to this day.

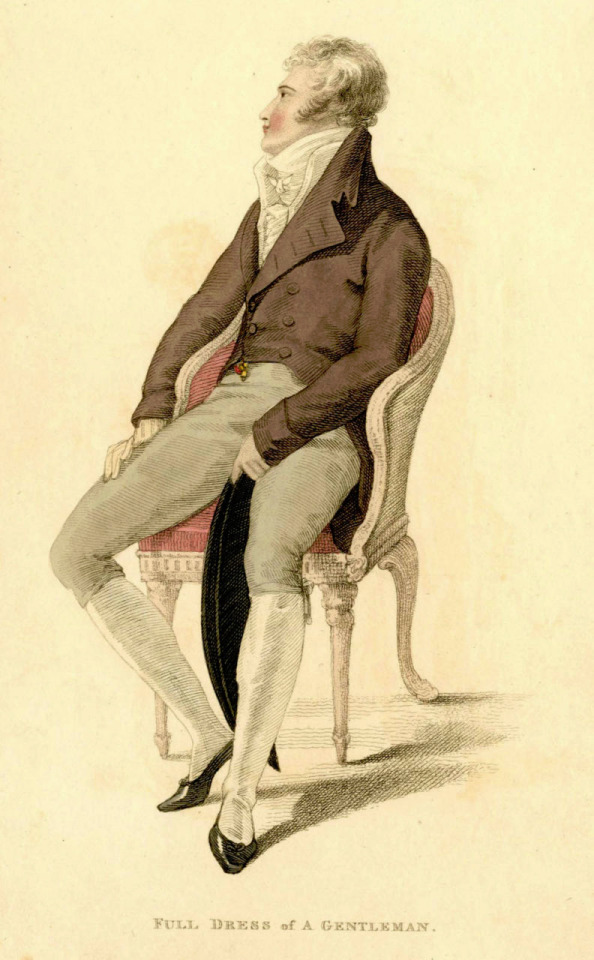

My point is not to in any way deny Beau Brummell's influence on Regency fashion. He was the most influential fashion icon for men in his era after all. I hope this just made it very clear that these bigger changes are not about individual people but much larger shifts and movements in society and culture. His actual influence was popularizing some of the English countryside styles, that were already part of casual fashion, as more formal fashion in the London high society, making extremely elaborate cravats into the fashionable items of the day and becoming the image of the English dandy.

The picture of him above shows him the typical English countryside suit with dark blue tail coat, white cravat and light pantaloons with polished hessian boots. He helped to make the outfit and pantaloons in general fashionable. Breeches would stay as the formal leg wear for some a decade still, till young fashionable men would start to use black or gray pantaloons in formal events too. Pantaloons, which originated from military wear, were very fitted, basically similarly constructed as breaches but long. The trousers, which were looser than pantaloons, had their moment in France during the Revolution, but because of their Revolutionary and working class association, they didn't at first pick up in the high society, especially in Britain, until 1810s. They stayed as casual fashion through the Regency Era and only started gaining formal status in 1820s and 1830s. Beau Brummell is credited for inventing or at least popularizing trousers that have strap to go under the foot in order to keep them straight. Here's first a painting from of a gentleman in a very country style emphasized by the setting. Then a illustration from 1810 of a full formal dress with breeches and a fashion plate from 1817 of day wear with trousers.

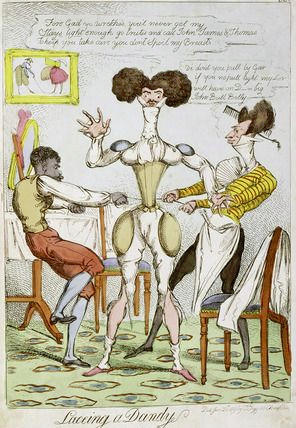

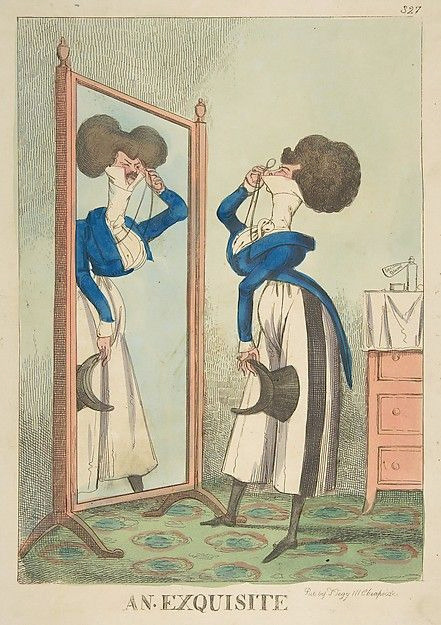

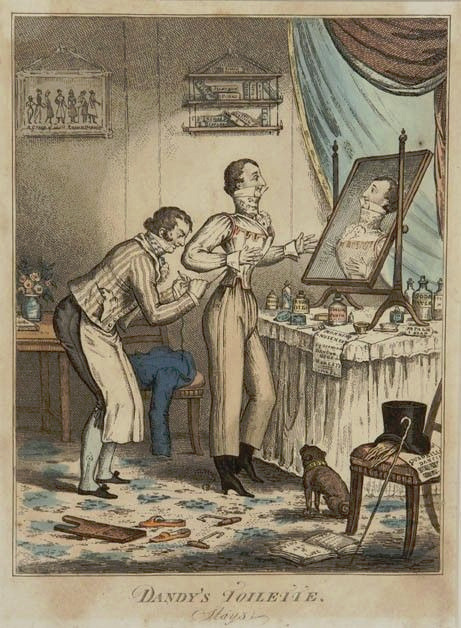

The thread also misses what dandy really was. Dandy was the embodiment of the middle class social mobility of the modern era. He was the "self-made man", the fashionable middle class and the new celebrity of a post-feudal era. He dressed in refined fashionable countryside middle class clothing and was celebrated for his style and refinement, not for his birth. Ironically though, there was a distinct reactionary quality to the Regency dandy. After all dandy did not embody social equality, but mobility. He was the ideal man of the capitalist hierarchy. A bit of dilemma for the dandy was that being extremely fashionable was central to the dandy, but after the French revolution being too fashionable and too concerned about looks had been associated with the aristocracy and was now therefore unmanly. Which is why dandy quickly came to be seen as effeminate. There is a lot of satiric cartoons from the time period that make fun of dandies and their preoccupation with fashion and looks. Here's couple from around 1810s.

In conclusion it's pretty ridiculous to say modern men's fashion was all created by one guy. The real reason why men's formal suit (and to be clear more colorful and elaborate styles have come and gone from men's informal fashion during that time) has been what it is for more than hundred years is because much bigger changes, like capitalism, colonialism, Orientalism and white supremacist patriarchy.

#i'm real sad though about this episode since princess weeks is the quest!!!! i love her videos#i still very much enjoy the podcast though#i will just keep avoiding any episode which deals even remotely with dress history to preserve my mental and vascular health#and maybe check the sources more often especially in subjects i don't know anything about#i hadn't previously seen him using this overwhelmingly bad sources#like i can accept in a podcast some less reputable sources if there's at least couple of high quality ones#a lesson to always practice critical thinking even when it's a source you usually trust#that includes me#like i hope none of you take my writings as some authority#i might i have blind spots i don't realize and i do make mistakes#i know i haven't in the past been super great at sourcing my posts#i'm just bad at being organized in my research and saving all the sources when it's not academic writing where i have to make the effort#but i will try to do better on that front so you can better make your own judgements about the validity of my posts

683 notes

·

View notes