#i almost died reading joan's image gallery

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bro who did this

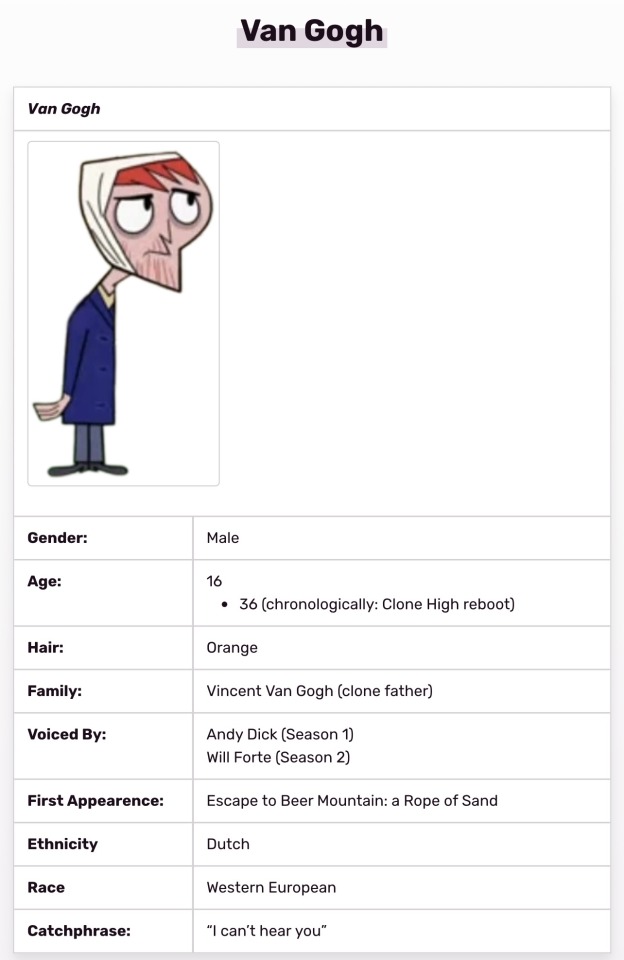

#i'm gonna add on bc omg#i almost died reading joan's image gallery#missing gandhi hours#scudworth = neil cicierega 😱#i regret looking into the comments on mr. sheepman page

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

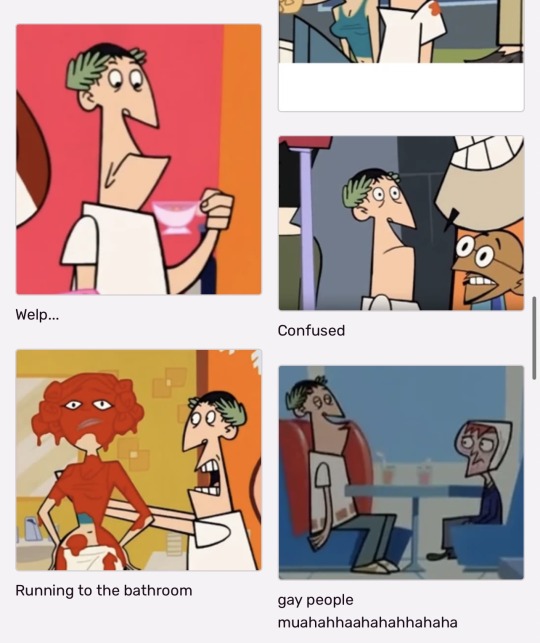

Artist Interview #1 - Jérôme Nadeau

William: So for redundancy's sake just I guess introduce yourself and the basic gist of what you’re interested in your work.

Jérôme: Yeah so I’m originally from Levis, which is across the river from Quebec City. And I moved to Montreal about 10 years ago to go to Concordia in Photography. I did my undergrad there and I did an MFA there that I finished two years ago. I also studied during my MFA in Gothenburg in Sweden. While doing my MFA I also a thing called Soon.TW which is a publishing house and then two years ago when I finished my MFA we actually turned the project into a contemporary art gallery which is right there. And at this point we decided to take over this space and turn it into an actual physical space. I was joined by two artists Jean-François Lauda and Nicolas Lachance, and then at some point in the process there’s Simon who joined us. Simon was in Chicago doing his MFA, we also studied together we did our undergrad together and then he moved to the United-States and came back. So we started that project. In my practice I’m interested in photography and like I said before, mostly in the process of photography so what’s usually left unseen from the photographic process. Exploiting photography for what it is. Kind of a challenging indexical link with reality.

William: Did you start your art experience with photography or?

Jérôme: No I actually started, well in Cegep I studied film-making and by the end of that I realized I was never going to do that. I’m still really interested in cinema and yeah I still think it’s the most amazing medium in the way that it has this kind of capacity to attract mass media even with very kind of-

William: Artistic?

Jérôme: Yeah artistic aesthetic or philosophical kind of questions and it’s something that goes beyond any other medium which I think is interesting but it’s this thing where you have to collaborate with many people and I don’t know… I’m not a fan of that industry which is something that is always a long process to be able to achieve that and I saw that coming quite early. I mean what you need to do to be able to make it I guess in this world. At this point I finished studying filmmaking and then I went travelling to Australia. And I was like should I buy a video camera or a photo camera and it was kind of at the beginning of digital photography being kind of affordable so I bought this digital camera for a few hundred dollars which is now completely obsolete. I’ve kind of learned to photograph through that, like there was a manual mode and I started to kind of experiment with it and I really-

William: So then you learned photography digitally before eventually going back to analog?

Jérôme: Yeah exactly but again I was at this point interested in abstraction. I remember the portfolio I submitted for Concordia for the undergrad was a lot of like longer exposure and colourfield photographs and it was all not necessarily very straightforward and I was also very interested in painting but I have absolutely no talent in painting and no patience to…

William: To get better?

Jérôme : To get better and I’ve never been formally trained as a painter so I like I remember as a teenage kind of, like in the backyard making this huge kind of Riopelle painting. Like I had a lot of fun with the process of painting but just, yeah I was lacking this kind of training that would allow me to get better. Or be able to actually do-

William: Like take something from your mind and put it onto the canvas?

Jérôme: Exactly, exactly. It felt like it was really limited but I was very interested in painting and I remember I had an art history class and I was interested actually with Canadian painting. Painters like Riopelle and stuff like that. I remember Riopelle because he died on this island called Isle-aux-Grues which is not too far from Quebec city, it’s in the middle of the river and my mom’s cousin has a house there so yeah I just remember seeing his work and at the National Museum in Quebec (city) and being kind of… really transported by his practice. I never really had a contact with art growing up like my family was just more involved in sports and stuff like that. So I remember walking into that museum and just kind of, I don’t know, really amazed by that painting. You know what I was saying about cinema? Like I kinda found a little bit of that in his work you know so I was just feeling stuff and is that even possible? Like you can’t really understand that from just reading about it or having a slide lecture in Cegep about it. So I was kind of mystified by that in a way but then again it was such on a large scale so this understanding of materiality that was kind of beyond me.

William: So do you think that experience informed your future work?

Jérôme: Oh yeah it informed the rest of my life. Like I remember that moment and they still have that painting in a permanent collection and I go back almost every year to see it. And there was this big show he did at the end of his life called the: “L’hommage à Rosa Luxemburg” because he had this relation with Joan Mitchell, the American painter, and when she passed he started this 120 meter long painting that’s an homage to her and it was shown in its entirety. It was bought by the museum now so it’s on permanent view and last year they actually made a show of Joan Mitchell and Riopelle too which was kind of interesting. So yeah I grew up with that-

Wanda: How young were you when you saw it?

Jérôme: I was in High School when I saw that for the first time so it just stuck with me and this kind of part of my life life where I started being more aware of like… culture in general but at this point there was internet but it was harder to find independent movies and even in Quebec city to find this kind of more edgier stuff.

William: And yeah especially in Levis too.

Jérôme: But a young age I started working in Quebec and getting involved in music a lot too. The electronic music scene was kind of beginning so I started being involved a little with film-making and a lot with music at this point. So you know I started making music, producing music, it was the beginning of what they call laptop techno. So you were moving on from vinyl and actually the programs like Live just came out and so it was quite easy to make music in your bedroom.

William: Do you think music still informs your work in some way?

Jérôme: Yeah, yeah totally. I mean not necessarily in terms of production because when I moved to Australia there was this, I don’t know, it’s still pretty expensive to buy records and just kind of constantly invest in all of that so I decided to travel and I started focusing on photography and when I came back I applied for Concordia while I was away and I got back and moved directly to Montreal to study. So I already made my choice to pursue visual arts and that music was not going to be a number one priority but its always been there. Like I’ve DJ’d for the past 15 years as a side job so I think it’s more this aspect that informs my work. Well not that it informs it but I feel that-

William: Do you work with music? Like in your space?

Jérôme: Oh yeah I listen to music all the time like if I don’t have my headphones there’s a good chance I’m not going to the studio. I know that there’s a lot of artists that can’t work with music but with me it’s just the opposite.

William: I kind of feel the same way when I do any sort of series I make a playlist specifically for it and I only listen to it when I working on it.

Jérôme: Yeah, sometimes I’m not even listening like I know, I don’t do it here as much but when I was doing my MFA I had a studio in a basement of the VA so there was no signal whatsoever so I could listen just to the same song over and over. It’s just you know especially physically when I’m working you don’t really listen to it. And there’s this thing where I feel, not with painting but with working even just on the computer, where you really get in the zone of something. Like it just feels like a different state of mind and there’s a lot of exterior signals that can be blocked out. But I just feel that music is just filling this weird void and it just allows me to focus. But sometimes you know if I do more quiet operation I listen just to white noise but I need something-

William: So you just essentially need noise?

Jérôme: Yeah

William: Does it, like are you looking for a mood or just a feeling while working or?

Jérôme: Hmm not necessarily I mean it informs what I’m listening to. But yeah it just gives me this form of energy. Especially when I’m working with headphones, it feels like I’m really blocking out the exterior and allows me to go deeper with my thoughts and with what I’m doing. That’s the only thing that’s happening is what I’m doing right now which is nice.

Wanda: If you’re in the space by yourself, do you ever listen to the music with no earphones?

Jérôme: No, no, then I get scared because someone would walk in and I’m just there with my headphones playing super loud.

William: Yeah I can only work with headphones too, I think it’s the physical part of having something in your ear that help block out those signals that you were talking about.

Jérôme: And when I’m writing I can’t really listen to any music, it has to just be sound. Or I have earplugs too sometimes. So I think it has something to do with my ear, maybe they need to be blocked.

Wanda: How do you see yourself or express yourself through your work?

Jérôme: To kind of go back to what I was saying with music and cinema then photography. I started at Concordia and the first thing we’re doing in the 210 class, you start working in the darkroom. Then I got really absorbed by the process of it. Like being in the darkroom. Especially starting with a digital camera where you take an image and then you put it on the computer screen you don’t really question it. It just appears there and it’s kind of magical but you don’t really see it as a physical thing. Then working in the darkroom and learning the basic of the film and I was really interested in the colour theory and physics behind photography. The mistakes that would happen in the darkroom too because there was a lot obviously. But I feel like something that informed my work up until now is following what messed up and try to accentuate it and always playing. I feel like the more I learned about the process of photography the more I could dismantle it. To just focus on certain specific areas of the photographic process.

So I guess what I’m trying to achieve… it’s a really hard question. It’s not that I don’t think I have anything to say. I just feel we feel in really complex times. Specially medium specificity and setting up these things it’s the process of photography that’s speaking for itself it’s not necessarily me. It’s funny because it’s always what I’ve been interested in, just the process, physics, and theory. And someone once mentioned to me it’s also a way of hiding any sort of personal expression from the work which could or could not be seen as a reflection of my personality. But coming from that person it really stayed with me. It’s what really motivated me a while later to introduce the writing in the actual work. So it’s a way to make something about the process a bit more personal through poetry and through self-expression that I feel a strong connection through poetry and visual abstraction. I feel that it’s functioning the same way. Obviously one is more visual than the other one but I feel the end process in your brain is quite similar and I thought it was a way to do that. And obviously even that isn’t really straightforward but for me there’s a connection to an event or a moment or person, something like that. It could be reflective, even if it’s abstract. I can look back at older work, me having produced that, it’s a moment in your life and it transports you to where you were. But for everyone else it’s not possible to achieve that. So I feel that leaving little clues can make that happen.

William: When did you realize you needed to have a studio space? And when you were trying to find a studio what were you considering? Did the image in your mind translate into reality?

Jérôme: I’ve always wanted a studio space. I was hanging around painters and I mean I had a studio in my apartment for awhile. I lived with a roommate and we had this huge apartment so I took the dining room and made it my studio. But at some point I was working with chemicals so I had to work outside and it just wasn’t convenient to do that in your own house. But I mean I was obviously restricted by budget and when I started the MFA I was pretty excited because you have a studio. Then I realized in photography you don’t really have a studio it’s an office on the same floor as where the labs are so I was pretty disappointed. But I started working in the spray painting room and using that but everything was scattered and always at school so it didn’t really make sense to have an outside studio at this point. When I moved to Sweden I was told it was the same thing that in this program you have this huge studio and some people even lived in it but when I moved there they decided to transfer me into the photography program and the photography program only had offices too so I was like are you kidding me. But they found me a little place in the basement where I could work and I came to Concordia and I applied for a studio in the VA which is more of a traditional space. I could do anything, and I really liked it. It was really small. Maybe half the size of here, no windows, I would just close the door-

William: And it was kind of like the earplugs?

Jérôme: Exactly. I could just close the door, no computer, it was just work. So I feel it was a really productive time. Then after your second year of your MFA you don’t have access to a studio anymore so you still have access to the facilities but you don’t have a physical space that’s assigned to you. So during that summer, my friend Étienne was subletting from Alexy and was going to Glasgow. So it was a last minute thing. I was working and I asked him what are you doing with your studio when you’re leaving? And he didn’t know so I was like ok I’m going to sublet it from you. So I worked here for that whole summer. It was while he was gone that the lease was transferred through Vincent. And Vincent asked if I wanted to stay since we’re doing this photography based studio and I said yes. Étienne came back and for a few months I was in a corner and we decided to share the space for that time.

Wanda: You’ve had studios with other people and by yourself, do you think you express yourself differently when you’re sharing a studio versus when you have a space to yourself? Also do you think it shows in your work?

Jérôme: Yeah totally. Now that you’re saying that I’m thinking that I had another studio for a few months in that building on Van Horne & Parc but it was before they renovated it. My friend he had a studio there for a year but the studio was maybe as big as both our studios here. There were like six people there And he had this big table and he’s doing collage… but I never actually worked in there I used it as storage because it was at the moment that I had to leave the studio at Concordia before I found it here. So I moved some of the stuff from that office there. But when I found this studio it was pretty much empty, just a few paintings tossed up along the wall so I had this whole 600 square feet space to myself. So I was like yeah...yeah I don’t want to be with six people in a small space. But sharing the space with Étienne was great because we were really close friends and we had the space open and it was messy. We had a beam here and he would hang stuff so there was some separation but then we decided to build this wall so even though it’s a shared space it feels pretty private. I can just close the door here and work without being disturbed. We’re also pretty quiet and respectful here so if someone is working we don’t just knock on the door for anything. Especially being here, it happens quite often that people leave and don’t even know so they lock the door so it feels like it’s my own studio.

It’s also pretty convenient with the gallery being there because I can work while tending the gallery. And now it’s pretty necessary because we sometimes have to use the studio as storage space.

Wanda: Do you see a change in your work when you’re working in a studio alone versus with a lot of people?

Jérôme: I couldn’t really do it with a lot of people like let's say right now I’m working on a lot of different stuff at the same time so there’s a lot of stuff that’s not resolved and I don’t necessarily want people to see that. And it’s where having the gallery is a little inconvenient because if there’s a vernissage we’ll do a bar here and it’s open so I have to clean. I don’t want this stuff around that I don’t want people to see. But then again I could decide to leave it closed but I don’t really mind that. I think it’s actually something that’s a good exercise, knowing that some people are coming over. Like if you’re having a studio visit you can pull some stuff out. Especially when you’re in the process of making your work, to look at all your work. It informs you And the way I work, I try not to work series even though it’s really difficult especially when it comes time to mount a show and propose a show. To dig in a whole lot of different processes and see how they talk to each other. And that, to follow back to what you were saying about music, that’s where I find a link. Especially with DJ’ing and mixing. There’s a whole lot of digging and using things that you couldn’t really see together and when you put them together there’s this dialog that opens and goes beyond the individual work that starts to speak. That’s something that I like, it’s not really something that you can see and just sit down and say oh I’m going to do that. Sometimes it’s just by chance, I’ll be pulling stuff out from boxes and then I look at them and say “oh my god!”. It could be formally or in the content or me and how I see it, but there’s a connection happening. That’s something that I really like and try to do and so when people do come over it’s a chance to do that and rearrange and look at your work in a different way.

William: Since you’ve already built and organised a studio, is there anything that you would warn against to anyone building their own studio or just general advice?

Jérôme: I guess it depends what you want to do. I guess build clever storage. Here we’re pretty lucky because it’s outside the studio but I feel before we had built that storage space I had accumulated stuff from Concordia, from the studio I had at my house, the studio I had on Van Horne so there was stuff that would pile up and it’s nice to be able to have storage. But then again I would advise against keeping too much stuff. I feel that again with the studio visit it helps to at least once or twice a year to do a cleanup. Go around the studio and get rid of stuff, it’s important to keep some because you’ll never know what you’re going to need but personally I feel I tend to hold onto things for too long and it just weighs on you. So it’s nice to clean everything out and get a fresh start. Which is something that if you go on a residency like when I went to Sweden I don’t have a studio I have nothing at this point. So you can very easily restart and you’re not starting from nothing you still have all these ideas and everything you’ve previously done that’s in your mind. That’s usually where it starts and you can start to experiment with new material and new ideas and I feel it’s nice to provoke that sometimes. Like I’ve rebuilt the table this summer and I completely emptied everything out and took everything out of the storage right after a show where there was tons of accumulation of images and tests. And I decided to move over that I was done, time for a new chapter. So yeah, be organised with the way you’re putting stuff in storage because oh someone wants to see a piece they saw online and you want to rework on it and you go and try to find it and it’s in a box that isn’t labelled. It’s quite a nightmare sometimes.

William: Is there anything in here that if you had absolute omniscient power to change anything in the room, what would be the one thing you would get rid of, add?

Jérôme: Repaint the wall and plaster everything. Especially because it’s years and years of oil paint. If I could sand it all out. And while I don’t mind the floor being dirty it’s just that it’s not sealed and has so much dust stuck to it so I would fix that. Maybe the ceiling too, make it more soundproof. We’re pretty lucky now it’s quiet I don’t know what’s happening maybe they’re freaking out because they know the building just got sold. I don’t know what they do but they I feel like they always have these I think it’s clothing racks moving and it’s almost scary. Probably why I’m listening to music so loud all the time but sometimes it’s annoying.

Wanda: Do you personally feel as though you work better in situations of controlled chaos or very tidy?

Jérôme: It’s a mix in between, like Étienne that had this other part of the space, have you seen Francis Bacon’s studio? It was exactly like that. A mountain of fucking shit he bought from Dollarama and just complete mayhem. So you know when you look at my studio compared to that it was the most organized thing in the world. But it’s always a play between resetting everything. Everything is organized and cleaned up but I need stuff laying around to play with and remind myself. So it’s cyclical. I would say I’m quite organized but I’m not insane about it.

William: Yeah you’re not like Georgia O’Keefe levels.

Jérôme: Yeah exactly, I wish I was like that. I’m like that in my house but here, maybe if I had a bigger space I could do that and I’d have a clean area. An area for printing and an area for experimenting with other materials and dirty practices. So I feel I could do that. Have an area that’s restricted by different processes.

William: What do you use most often in your studio?

Jérôme: I mean computer I guess but I wish it wasn’t that answer.

Wanda: So how long did it take to get the studio you wanted it to be or are you still evolving it?

Jérôme: It’s changed a lot. Like we built the wall a year and a half ago. So that changed a lot. When I got the printer I changed a lot of the configuration. I mean I’ve accumulated a lot of stuff. There’s also a moment where I was living in this really large apartment and I moved out so there was a lot of stuff like books that I had at my place that I moved here or in the storage. But I feel like it’s been like this since the summer, like I said I rebuilt the table so I built this platform underneath that works as storage. So it feels like it’s constantly changing.

Wanda: Did you have any inspirations when building it? If so who were your inspirations?

Jérôme: No, I mean it was about practicality. Stuff that I found. Nothing really belongs to me here. Like there’s some wood panels that I found and this someone gave to me [legs for desk], and there were so many ex tenants that left wood that I used to build. Lot of finding stuff. Even the table I mean most simple studio table you can build for cheap. If I could build the ideal studio I guess the inspiration would be Donald Judd’s studio in New York and Marfa. He even left instructions when he died like the little rock there and the pen. He was a collector and has all these books, built everything and designed everything himself. If I had more space I wish I could do that. Even here doing renovation, you start cutting wood and there’s wood chip everywhere.

William: And the into the floors must be a nightmare.

Jérôme: Yeah if I do that there’s also the other studio so it’s a bit difficult. We’ve been through quite a bit of renovation. Painting the walls and rebuilding the whole gallery space about two years ago.

William: Universally, what do you think is a must for any studio? Like one thing that every artist should need.

Jérôme: An exact-o knife.

William: And what do you use yours for?

Jérôme: For everything. I don’t know. Not that I’m dealing with collage but like if you need to cut a piece of paper. Mine was lost for awhile, I left it in my friends car-

William: And you were lost without your exact-o knife?

Jérôme: Yeah and it was a really good one with the black blade that I paid thirty dollars for. And he said like “oh I have the same I kept it” and he never gave it back to me now that I think about it. I feel like it’s the thing that especially after realising that it was gone for awhile.

William: You don’t know what you have until you lose it?

Jérôme: Yeah. Yeah. So I guess that and headphones.

Wanda: Do you find yourself stressed when you’re working here or do you find that it relaxes you?

Jérôme: I don’t think the studio informs that, it’s more about what I have to work on or if I have a deadline.

William: Is there a part of the process that you dislike or like more than another one then?

Jérôme: Not really. I like starting a new project because usually you have more time and it’s easier to place your ideas and there’s this playfulness. But I also really like the last stretches, putting up a show and deciding. Having people over looking at your work and seeing what you’re going to present and doing studio visits that are really directed towards what you’re going to show. I really enjoy that when everything is done. Like I was saying when I was doing my MFA I was working with my teacher and adviser a lot. I would just bring boxes and boxes of work that I had done throughout the year on her table and we would play with it. So I like that. And I try when I’m working to not overthink it. I just get it out. Work and experiment, get stuff out. And then when I’ve accumulated enough and I find something that makes sense I can take a step back. Start to think about it, see how it situates with ideas and theory and see if it makes sense. If there’s anything happening between the works.

William: So then is there a prevailing emotion when you’re in here or is it really just based on what you’re currently working on then?

Jérôme: I guess it really changed throughout the years. Like at some point I moved out and I was I was in this weird thing where I didn’t have anywhere to stay. It was just a lot of change in my life. So the studio became this place where I was here everyday. I would just work a few nights a week. I was just here all the time so I think it was not really good because it just became my second house. Like I would come here even though I didn’t really have any shows planned. Work on the computer, make some tests, and then Jean-François would be here and we would just hang out and there was the gallery so I wasn’t really coming here to work. But again I feel like it’s sometimes good to be in the studio all the time. I kind of miss it. Like sometimes I would put that on myself. Like this summer it was insanely, insanely hot in here. It was unbearable so there was this whole month after a show where I told myself I can’t be in here. I’m forcing myself not to be in here. Because sometimes you want to work on something but you know you’re not in the right state of mind and work for nothing. So it was nice to miss it and when I came back and put everything in order I felt this renewed energy from me not being here everyday for a whole month when it was 45 degrees.

William: Did you work outside of your space during that month?

Jérôme: No I just read, researched, and prepared the class for Concordia and thinking of the facilities there. So how I could work there. So it was more like making lists of things I wanted to do with those facilities, knowing that I would be here and that I’d have access to a lot of stuff I didn’t have access to before.

William: Do you think then that it’s important to sometimes take a step back away from your studio space and organize your thoughts?

Jérôme: Yeah for sure. Since it’s hard for you to do that when you’re in the space working. So it’s nice to impose that on yourself as a constraint.

Wanda: Do you have any recommendations then for people who can’t afford to have a separate studio? Like a lot of the times they end having a living room or in their bedroom, do you have any advice?

Jérôme: Yeah I’ve done that for a long time and it’s personal. I know a lot of people love to have their studio in their space. With the winters it’s more convenient. I like the idea of going to work but I know it’s a lot of money and not only that you have to find a studio not too far from your house. Who you want to be with, who are you going to be sharing with? So there’s all these questions. Like mine was in my room for awhile… that I would not recommend except you can’t have it anywhere else. It’s nice to keep your room for sleeping, it’s healthier that way. But then I had this dining room that after a year we made diner and invited people once so I’m taking it over and I was paying extra and my roommate had a bigger room so it was this common agreement we had. It just made sense and it doesn’t have to be big it just has to-

William: Be somewhere to be productive in that space?

Jérôme: Yeah and your stuff is there and you know that when you go there you go there to work it’s not like you’re working from your couch or your bed. I even do that for writing like I can’t write in here.

William: Because it’s more visual?

Jérôme: It’s more visual, like I always want to work on something else when I’m here like I look and there’s all these ideas and I need to be in a neutral space. Like the library is good for that, in my house I set up a space where I write so it’s nice when you have a space dedicated-

William: For specific tasks?

Jérôme: Yeah specific tasks, function. When you go there it feels like your mind is already settling into that mode. Even reading like I don’t see the point in coming here to read, I’ll go to the library, a cafe, or outside if I can.

Though actually if I could change something about the studio I wish there was more space where we could do this and be more comfortable. Have people over. I know Marc Seguin would invite people over all the time; collectors, curators, friends-

William: Have almost like a social space, like an old coffee house type of thing.

Jérôme: Yeah and again with Jean-François it was always like that. End of our day and just have a beer so you hang out and it’s nice when you have the chance to do that. Have conversations and talk about your work.

William: So you think it’s important to be able to have that social aspect?

Jérôme: Yeah I guess it’s really personal but I feel like, I give meetings with people here and most of the time it’s convenient because I’m here working. It’s another reason why having a studio outside of your house is nice because I had studio visits at people's house and you like judge everything it’s not comfortable for the other person for like an hour just standing there in someone's house. So it’s nice when ok you look at peoples work but you can sit down and relax, talk. But yeah it’d be nice if the space could function like that. Because collectors and curators you’ll have studio visits like so to be able to make the space as nice as possible would be cool. Also makes it go for longer.

William: Like ow my legs are hurting

Jérôme: Yeah and the chair is full of paint and you don’t want to touch anything. But then again some people might like it if you go to place and it’s just mountains of shit laying around and work.

William: I mean personally I wouldn’t want to go to Francis Bacon’s studio. That place looked insane.

Wanda: I would love to go like you’ve seen my room I wouldn’t be too upset.

William: Yeah but can you imagine doing a studio visit there just standing there for hours?

Wanda: Yeah can I move this pile of trash to this side of the room for one second!

William: It’s not trash, needs to be right there!

#artresidency#artistseries#montreal#montrealart#artstudio#artistspace#artist interview#interview#film photography#photographer interview#canadian art#quebec art#concordia university#concordia

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ode de Kort

A young artist, her sculptural experiment and the recurring ‘circle’.

Nederlandstalige versie

Date of interview: May 7, 2017

Estimated reading time: 15 minutes

Ode de Kort (° 1992, Malle, BE) grew up in the silent ‘Voorkempen’ in Flanders, Belgium. As the granddaughter of sculptor Jan Dries, she grew up considering form and thinking about art. Before finishing her master photography at KASK in Ghent (Belgium), her still blossoming oeuvre was picked up by Giuseppe Alleruzzo from SpazioA in Pistoia, Italy. It was here that she launched her first solo exhibition at the beginning of this year. In this exhibition, 'O froooom O toooo O’, the circle shape - for years an old friend in her work - formally received its central place: in the title. Exercise, play and repetition are central to the production process of de Kort. In her sculptural experiment, the artist tries to stretch the boundaries of the photographic image by pollinating them with a mix from other disciplines.

De Kort also showed work in CAB (Brussels), Extra City Kunsthal (Antwerp), Hopstreet Gallery (Brussels), Tique Art Space (Antwerp) and De Directeurswoning (Roeselare). About early-age success, the artist says, "I try to look at it in a practical way: either you make work or you don’t. The rest will come.“ According to de Kort, she inherited that do-mentality from her grandfather.

On the day of the interview, Joan Panhuyzen (the TSUA photographer) and I meet each other for a coffee with breakfast in the outskirts of Antwerp, where we have a brief talk about de Kort’s work. Choreography, the subtle control in her meticulous arrangements, the encounter between sculpture and photography, circles of course, and whether - and where - humor shows in her practice. When the young artist finally leads us in, she immediately starts talking about her studio and new book (a co-publication with Silvio Ebner and SpazioA Pistoia). As she introduces the book to us, it almost seems like her hands dance with the pages. A pleasant experience that we detect a few minutes later again when de Kort demonstrates her relationship with a certain rubber circle.

Ode De Kort

SpazioA

The work from my grandfather is my most treasured possession.

You grew up in a small family as an only child. One of the main characters in your life was your grandfather, sculptor Jan Dries. How did you see him?

My grandfather made an imposing impression on me as a growing child. I was sensitive and did not always like the things on my plate. He was strict but fair. Later, I mostly had philosophical conversations with him. My higher education started at the same time as the beginning of his health problems. In 2014 he died. We actually have never been able to talk about my work in a mature way, and that still pains me.

What is the most important thing you learned from him?

His 'do' mentality! Also that you always have to listen to yourself and that stubbornness is therefore fully permissible in that regard (laughs). When I turned 23, my parents gave me a work of his for my birthday. It's called "Toetssteen". If you push it, it always finds its axis back. I can manipulate, move and tilt it, but it always comes back to its natural balance. That's powerful, right? That work is my most treasured possession.

Your grandfather worked in his later artistic life mainly with white Carrara marble, a material that he remained faithful to until his death. Also in the last year, you have explicitly chosen a lot more for one form: the circle and its derivatives. In the sense of self-discipline and faithfulness to one recurring motive, I see a clear resemblance between you and your grandfather.

First I want to clarify that my grandfather has done a lot of different things in his life. He started with ceramics, in his earlier work you find a lot of color and he could draw amazingly well! Only after a long time he decided on white marble. Light began to take a more essential place in his work. How light functions and moves for example. Then Carrara marble was a logical switch for him.

It’s no devised plan for the next twenty years (laughs).

With a few objects I've been working for a couple of years now.

But to return to your statement: I think it's because of a certain attentive-ness with which I grew up. My parents and aunt are also very attentive and notable people. Once Pieternel Vermoortel said that I could easily work for five years with one stick or one circle, and she was right. With a few objects I've been working for a couple of years now. Exercise, play and repetition are important motives for me. Some may find it too monotonous to always re-use things again, but on the other hand I find it admirable to make a choice and stay behind that. Just look at an artist like Daniel Buren, whose work is characterised by the persistent use of vertical stripes. You can say, “They're only dashes", but of course then you totally miss the point. However, I do not know what camp I'm in yet. It's just happening like this now. It’s no devised plan for the next twenty years (laughs).

More recently I began to see that the circle often returns. At one point I made a radical choice.

Pure photography does not affect me too much.

Your first circle is already visible in the work 'Frozen Movement' from 2013. After that, in the Fold / Unfold work from 2014 and 2015. Was it always there to begin with?

Until last year, the recurrence wasn’t a conscious motif. More recently I began to see that the circle often returns. At one point I made a radical choice. Curator and founder of KIOSK in Ghent, Wim Waelput, invited me to the Hopstreet Gallery (Window) in Brussels and the video I made for this show, Suspension of a Circle (2016), was an important moment. For 9 minutes you see a rubber circle manipulated and played by with a stick. The fun and the movement, both crucial in my work, get their place in that video. Then I made an installation for Extra City Kunsthal in Antwerp with circles in the floor, which was part of my work '0O (2016)'. Also that was another step forward for me. I graduated as a photographer and during my studies, I was constantly searching for how I could stretch and activate the photographic medium because I do not necessarily want to show the transparency of the world or copy reality. Pure photography does not affect me too much.

I graduated as a photographer and during my studies, I was constantly searching for how I could stretch and activate the photographic medium because I do not necessarily want to show the transparency of the world or copy reality.

Interesting. Are there photographers you do feel affected by?

Photography that is placed in a larger whole by a combination of another medium. I'm a photographer myself, so I am not completely indifferent, but I find that it doesn’t stick with me when it works purely photographically. Naturally, I have a love for the sculptural experiment of the photographer, as I'm searching into that field myself. Artists that attract me greatly are Joëlle Tuerlinckx, Helen Marten and Michael Dean. I think for now, it’s rather difficult to call artists ‘just’ photographers (laughs).

Naturally, I have a love for the sculptural experiment of the photographer, as I'm searching into that field myself.

What is the last exhibition you've been to that stuck?

I’m afraid that was also not a show from a photographer (laughs). The big room in the exhibition 'Listening the pressure that surrounds you (2016)' by Thea Djordjadze in Sprueth Magers Gallery had a big impact on me. Very subtle but beautiful!

How does your work stands in relation to the camera?

The camera is just one of the ‘bodies’ I'm dealing with. A concept is also a body in a sense. The material, which is autonomous, is another. The space, movement, the limitations, all bodies. I, as the maker of work, am the manipulatory body. The image is only created through the encounter between all those bodies. The camera is as important as the stick or the rubber circle. Not more, not less.

how people think about existing forms keeps me busy.

Where does the autonomy of your circles actually comes from?

Mainly from movement. I am interested in topology, a certain branch of mathematics which deals with deformations of an object in a space. But also how people think about existing forms keeps me busy. A cone shape for example. If you show his flat side, you'll see a circle. You can not see the depth behind it. My work 'Weight of a Line' from 2015 plays with a derivative of that thought. A line is a concept, not something concrete. You can not grasp or measure its weight. Just like a border. It only exists in our minds as a concept because we create a difference between one and the other.

Artists and intellectuals are ultimately the marginals of this world and that’s too easily forgotten.

People often forget that you, as an artist, are confronted with your work at all times of the day. It's like a flat hand in front of my eyes.

I am not always in the mood for people, bursting into your space like a hurricane, suddenly ‘getting’ your work all at once.

How important is it for you to talk about such ideas in your work?

I do not like lofty ways. Artists and intellectuals are ultimately the marginals of this world and that’s easily forgotten. On the market you also want to buy your vegetables with people who are friendly, honest and open (laughs). Do not get me wrong. I like talking about art, whether it's my work or work by another artist. A good conversation about something, however, needs the right context. Only from a sense of mutual respect, can real information be shared. When someone has decided what his or her opinion will be, talking sometimes makes little sense.

People often forget that you, as an artist, are confronted with your work at all times of the day. It's like a flat hand in front of my eyes. I am not always in the mood for people, bursting into your space like a hurricane, suddenly ‘getting’ your work all at once.

I was invited to a debate on social engagement in the arts. Being the youngest and only woman with four experienced men – three of them double my age - I was planning to wear a mustache. But I was too tired that morning for jokes like that (laughs).

You don’t want to defend yourself if people have a wrong idea of what you do?

Mostly not. It really depends on the person's openness. I've already heard crazy things about my work, but usually I do not mind that much. It’s also not always evident. A couple of weeks ago, I was invited to a debate on social engagement in the arts. It was an event that took place in Tour & Taxis in Brussels and the guest speakers were Wouter Hillaert, Jeroen Olyslaegers, Ben Van den Berghe, moderator Oscar Van den Boogaard and me. Being the youngest and only woman with four experienced men – three of them double my age - I was planning to wear a mustache. But I was too tired that morning for jokes like that (laughs).

Supporting attention to something, for 5 hours non-stop, is super political!

From my – maybe flawed - point of view, I was the suspected artist with "little socially engaged" work. But I find that aesthetics are not merely form but are certainly also political. Supporting attention to something, for 5 hours non-stop, is super political! That form of attention is still very rare in our society, I am afraid.

I don’t work with circles because I like the way it looks.

What are aesthetics for you?

I do not think aesthetics are mere form. Aesthetics have a whole agency. I also do not work with circles because I like the way it looks. I don’t know if shape actually exists independently.

I don’t know if shape actually exists independently.

You always really consider the exhibition space. Have you always done that?

Due to practical considerations in a space, you must move differently both with yourself and your work. I always start from the space now but that has been an evolution. As I mentioned before, I wanted to abandon the idea of framed photography that only hangs on the wall. I wanted to make the paper move in-space. The space, however, recommends it how to move, it dictates what can and what can not. I don’t want my work to be just an aesthetic object, therefor it has to work in the space.

I enjoy being busy with my clothes, my house and plants.

How important is shape for you in your life and work environment?

Very important. I enjoy being busy with my clothes, my house and plants.

Do you have a fixed rhythm?

No not really.

I need a lot of emptiness.

Do you miss that?

Sometimes I worry about that, but at the same time, I have to take my time for things. I always have to bear a difficult production process. My boyfriend, Boris Van den Eynden, works very different from me as an artist. He works from 8 o'clock in the morning until late in the evening, and in a sense he has concrete things to work with. I can’t implement it for myself though. Although I work very hard and certainly show the necessary professionalism and self-discipline. I need a lot of emptiness. It's just a very different fight.

I danced a lot as a child. I should actually do that again to relax. I often sit in my head for too long.

A fight?

There are some difficulties. For example, when do you decide that a work is finished? Deadlines work well for me. Restrictions in space and time often bring solutions.

By now, luckily, I know what process I need to go through if I want to create new work, but it still sometimes crawls into my body. In the beginning of a new production, I really have to go deep into myself and that is not always easy. To get rid of over thinking things, I sometimes draw: arrangements or spaces. Playing as such and having fun with materials is also important to me in the initial process. Look up the boundaries of my material, move, dance. From these things something can arise. I danced a lot as a child. I should actually do that again to relax. It would be beneficial for my work actually. I often sit in my head for too long.

During your studies you stopped dancing. You miss that?

In a certain way it is still present in my life. If I am, for example, making a video or a photographic image, I’m dancing with those objects. But pure dance, yes, I miss that very much! I need to move, I need an exhaust valve. I need things to let the tension out of my body. I'm actually looking for the right environment, where interesting choreography can be combined with my current physical disabilities (laughs).

You are talking about your need for relaxation. Do you use humor in your work to solve something?

No, it just happens sometimes. In the video 'Suspension of a circle' I had a lot of fun with the comic movement of that relaxed rubber circle slab. I always start from something that follows its own form and sometimes something unimaginably funny happens. This give some airiness to the work I guess. I always keep room for coincidence. Humor relieves. Sometimes it's also a discovery. Sometimes it doesn’t make sense. The comical aspect in my work is a very specific form of humor. Not everyone may appreciate it, but I notice that most people who see the comedy often follow my work better.

When did you meet your SpazioA gallerist, Giuseppe Alleruzzo?

I did a residence at Fondazione Antonio Ratti in Italy, where Giuseppe encountered my work and portfolio. We first "spoke" through email when he invited me to work in his project space. I met him in Pistoia when I built my exhibition. The experience was one of instant understanding and so we started working together after that.

Being an artist and dealing with an audience is confrontational, yes. You show yourself.

Did you sometimes feel you were too young to step into the gallery world?

When I met Giuseppe, I was still working on my master at KASK in Ghent, so it was important that I could still take my time for studies and residencies. Giuseppe has greatly supported me on that front too. For him, the relationship with the artist is the most important. I always had the feeling I was given the freedom to determine my own production rate. Also with his assistant Ariana, there is a huge ‘click’. I was really lucky with them.

I never felt I was too young to show work. Being an artist and dealing with an audience is confrontational, yes. You show yourself. Your work is critically reviewed by people. Exposing yourself is essentially frightening. But there are always uncomfortable issues. As I said, I try to look at it in a practical way: either you make work, or you don’t work. The rest will come.

I would love to make a playground once.

I am happy for you that you told us at the beginning of the interview, you don’t have a twenty-year plan. It wouldn’t feel healthy if you would have one at this age. However, I am curious about your plans in the near future. You just got your first solo exhibition 'O froooom O toooo O' in SpazioA in Pistoia, Italy. What's on your agenda now?

I will continue to work with my new book (a co-publication with Silvio Ebner and SpazioA Pistoia). In addition, I think that ‘performance’ still has an enormous capacity. Video, photography, sculpture, performance. There are so many interactions possible that new things will soon come. I'm back in the beginning of a new production process: an exciting moment always. Perhaps I urgently have to look for a suitable dance class for me. Against the tension in my body (laughs). I would also love to make a playground once. My idea is to just keep working and deal with everything as it comes.

Interview: Merel Daemen

Photography: Joan Panhuyzen

Editor English translation: Gary Leddington

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Anne Harvey’s Strange Painting of Tulips

Anne Harvey, “Fireplace” (n.d), oil on linen, 29 x 23 1/2 inches (all images courtesy Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects)

In 1971, a memorial show for Anne Harvey was held at Robert Schoelkopf Gallery. It would be her last solo show for more than 40 years, until now. An American-born artist who lived in Paris much of her adult life, and who did not align herself with any tendency or group, Harvey’s observational paintings were described by John Ashbery, in 1966, as “the probing anguish of an almost Jamesian dissecting eye.” Ashbery went on to state: “A curious anxiety, tempered by the exhilaration of her novel optics is the result.” Ashbery’s praise is precise, and his championing of artists such as Jean Helion, whose later work can only be characterized as Helionian, is, in my book, reason enough to give another look at this nearly forgotten artist whose small circle of ardent admirers included Constantin Brancusi and Alberto Giacometti.

Anne Harvey’s life — the first half of it, at least — reads like a fairy tale. She was born in Chicago in 1916. Her mother, Dorothy Dudley, and three sisters were involved in the arts, as biographers, poets, and theatrical impresarios. She was a prodigy surrounded by strong women who encouraged and supported her talent. Without getting bogged down in the biography, as interesting and complicated as it is, I should point out that she met a number of artists when she was young, all of whom recognized that there was something special about her. Jules Pascin drew her portrait when she was 18 and living with her mother in Paris. She met Brancusi around this time through her mother, who wrote about him in an appreciation that appeared in The Dial in 1927, after he had come to the United States for exhibitions of his work at the Wildenstein and Brummer galleries. Other artists who admired Harvey’s paintings included Joan Miro, Helion, and Alexander Calder, many of whom bought work from her. She died in Paris in 1967, at the age of fifty-one.

Anne Harvey, “Brancusi” (n.d), ink on paper, 12 1/4 x 9 1/4 inches

There are two wonderfully sinuous line drawings that Harvey made of the bearded Brancusi, along with two photographs he took of her in his famed Paris Studio, in Anne Harvey: Private Life at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects (May 10 – June 11, 2017). Harvey’s fluid line is not something you can be taught, which is why so many tough-minded artists admired her work.

It should be noted that Mr. Harvey, who owns the gallery and mounted the exhibition, is the nephew of the artist, which must make the occasion of her exhibition bittersweet. The show consists of paintings, drawings, and pastels she made from age 18 until a few years before her death. None of the work was borrowed. The subjects include still–lifes, landscapes, and portraits. The “novel optics” Ashbery speaks of is key to every work, whatever the medium. In her hands, observational painting attained a level of scrutiny and intensity we associate with hallucination. As Ashbery concluded an earlier review of Harvey: “Her show reveals a rare and original talent.”

Anne Harvey, “Two Trees and a River” (n.d), oil on canvas, 13 3/4 x 18 inches

In “Two Trees and A River,” the two trees are in the foreground, cropped by the painting’s bottom edge, of an elevated view of the Seine. Done largely in browns, gray-blues, pale blues, and ocher, the artist has made a series of different-sized abstract marks, which we might initially read as waves and reflections of sunlight, but that impression soon gives way to the pleasure proffered by the marks themselves, which seem to be floating slightly in front of the painting.

Harvey’s interest in the dance between mark-making and surface isn’t expressionist (Lucian Freud) or morbid (Ivan Albright). Vincent Van Gogh may have inspired the marks in the river views, but she does something different. Her marks are lighter and thinner, and quicker, making the scene more airy. Van Gogh’s turbulence becomes, in Harvey’s hands, odd and inexplicable. The marks are like accents whose necessary presence you cannot explain.

Anne Harvey, “Buildings, Paris” (c. 1950s), ink and gouache on paper, 100 1/4 x 14 1/2 inches

In the ink and gouache drawing, “Buildings, Paris” (circa 1950s), Harvey articulates walls, windowpanes, the accordion folds of shuttered gates, shadows and reflections. And yet, as busy as this drawing becomes, and the attention that is paid to stained walls, the drawing never becomes claustrophobic, which is miraculous. There is in this and other drawings an unerring sense of how much to include, and which spaces to fill with color or with lines. She can make a small space feel bigger and a larger area feel concentrated.

There is also a quirky sense of humor in some of Harvey’s work, such as the painting “Fireplace” (n.d.), where the view is of the fireplace’s cavity framed by a black mantlepiece, which takes up three-quarters of the composition. The painting invites us to stare at the black coals, with their blue, yellow, and orange aura. This is the fire that neither goes out nor warms the room. The subject might be homey, but the painting isn’t.

Anne Harvey, “Tulips” (n.d), oil on linen, 36 1/4 x 25 1/2 inches

Harvey is an observational artist who never settled into a style: each work was an adventure that might lead to something new, and often did. In these and other works, Harvey invites us to see beyond what is there. It is the kind of invitation that can arise out of familiar images associated with transcendental experience and matter becoming spirit. Not so Harvey. Matter stays matter in her work, while simultaneously becoming something strange. How else to explain the three stems in the painting “Tulips,” where each is painted two colors, the most prominent being orange and blue? Is it because Harvey knows we look at the flowers and ignore the stems? Are they meant to distract us from all the attention she paid to the variety of greens on the surfaces of the leaves, some of which appear to have dried out? Harvey’s subjects might be domestic and even sweet, but her paintings seem full of muffled misery. She follows the twisting curves of an ornate, inexpensive flower vase because the act of painting leads her away from her inward turbulence. Better to see what is not there than to remember what is.

Anne Harvey: Private Life continues at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects (208 Forsyth Street, Bowery, Manhattan) through June 11.

The post Anne Harvey’s Strange Painting of Tulips appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2qMZojB via IFTTT

0 notes