#he has been raised both to believe himself inherently superior and to equate value with how well one performs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

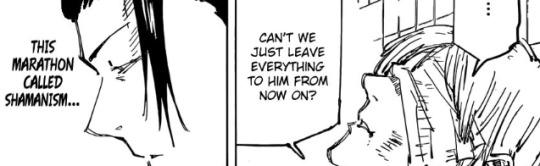

Getou vs. Monkeys

An analysis on Getou’s psychology, and how he can go from being a well meaning good guy in the Hidden Inventory Arc, to the extremist we see later in the manga. Read more on one of the best villains in Shonen Jump current under the cut.

1. Empathy is a liability

Getou is introduced to us in Hidden Inventory with a unique mentality among sorcerers. In the world of sorcery almost everything is decided either on bloodline, or individual strength. Getou is someone who always sympathizes with the weak.

It’s a philosophy that puts him at odds with Gojou an individualist, but also one that makes him uniquely complementary towards Gojou. Getou is someone who believes in the collective good. He believes the that you have to sacrifice things for the collective good of everybody. That the strong should have their freedom limited and be used in benefit of the weak. That the strong are expected to use their abilities for the sake of the weak.

Getou undergoes a transformation in this arc, but while he is radicalized and pushed to extremes he never actually changes his core beliefs all that much. This is a point that I will explain later, as for now I would like to explain how much Getou’s trauma in the hidden inventory arc had an affect on his world view.

Getou and Gojou are asked on a mission to protect a girl, only to kill her at the end of the mission. That girl’s individual life has to be exintguished for the greater good of everyone, which is something that conflicts with both Getou and Gojou’s world views in a way. Gojou believes in the power of the invidual, and Getou believes that the rules of society exist to protect the weak, not exploit them.

While Getou is a very principled person, he’s also a very empathic person. He wants to do good for society as a whole, but Getou is someone who also deeply sympathizes with individual lives especially the weak, and downtrodden. Getou is someone who will always sympathize with a victim, but that doesn’t necessarily make him a good person.

Getou is the first one to make a connection to Riko in the mission, and he already has a very personal stake in a girl that he’s known for one day, and is going to sacrifice at the end of the mission. He’s also the first one to figure out the connection between Riko and her maid, and how important she was to Riko by declaring them family.

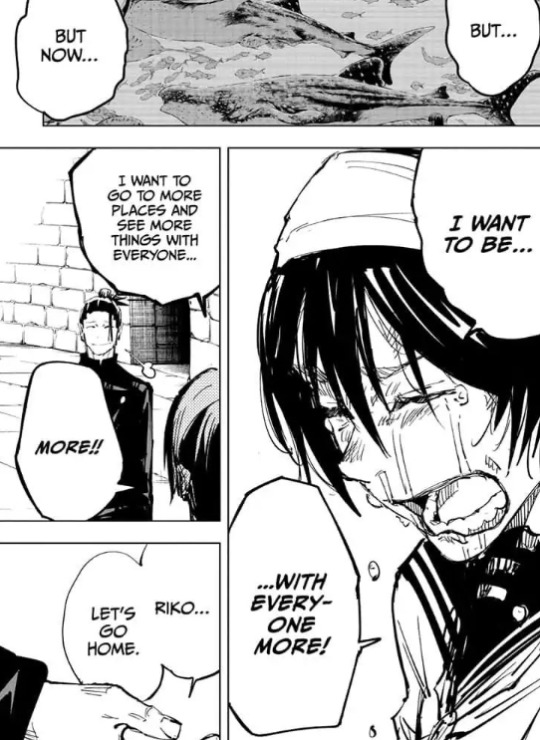

The reason why Getou starts empathizing so much with Riko is important as well. Consider the symbolism of this scene. Riko is someone who has spent her entire life unable to live her life. She was told she was not individually important enough to live. She had to sacrifice herself for the greater good of everyone. Riko isn’t allowed to make any choices in her own life because society has dubbed her unimportant. She is essentially, a small fish in an ocean. She’s all alone and can’t be with everyone else because she’s marked different as them.

However, when she watches the fish at the aquarium she sees them all swimming together in a school, all different kinds of fish. That makes Riko realize what she wants, to be with everyone else, to swim with them. It’s not about being individually big or small or important, it’s about being with everybody.

Riko craves a life together with other people. She’s important because she’s a part of this world too just like everyone else.

Getou who sympathizes with the individual so much he’s willing to side against the entire of Jujutsu Society and his direct orders from his superiors in order to allow her to live her life. Only for that life to be immediately taken in front of him. That is the source of Getou’s trauma, empathy and connection in the Jujutsu world is something that deeply hurts him because connection is not valued.

This is something we see over and over again in the manga. Characters longing for connection, characters wanting to be together with everyone (characters like Kokichi who repeats the exact same words when he makes his final standoff against Mahito, or Junpei who wanted to join Yuji even after losing his mother) only die alone. People want to connect. The system the world is designed around, especially the Jujutsu World, is unfair, heartless, and punishes connection.

Getou’s trigger for all of this is watching the nameless crowds all celebrate Riko’s death, especially since he later comes to associate that with how the rest of society is completely oblivious to the suffering of individual Sorcers who die horrible deaths for the sake of the greater good.

Getou is looking everywhere for justice in the world and the sense that he’s doing the right thing, but all he sees is corpses piling up, a small minority of people has to suffer for the sake of an ignorant majority. Not only that but the system that Getou is working inside is corrupt too, it assigns him missions like executing a teenage girl for the sake of everyone else.

It’s a system that does not value individual lives, and therefore pumps out teenage sorcerers only to have them die on the regular. It almost makes sense to respond to Jujutsu Society the way Gojou did, because Gojou by distancing himself from others and taking responsibility for everyone on his shoulders and becoming strong enough that no one can overpower him means he retains his sanity unlike Getou.

The incident that causes him to defect is just another repettition of this vicious cycle he sees everywhere. Two individuals who are hurt and rejected by an entire small town, and made to be a scapegoat by people who are completely ignorant. Getou sees this incident as a microcosm of jujutsu society as a whole, and that’s why he comes to reject the way the world is built.

2. Sinner of the System

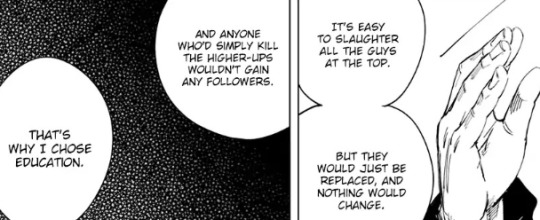

I’ve been too nice to Getou so far. Time for the second half of the post where I point out what a hypocrite he is. Getou’s actions are a rejection of Jujutsu Society pushed to their ultimate extreme. In his mind the only way to reform the current world is to completely destroy it, and establish a enw world order with Jujutsu Sorcerers on top. That is the only way he can see stopping the suffering of individual sorcerers. In a way he’s just flipped the equation, instead of a few suffering for the many, he’s taken out the many for the sake of the chosen few.

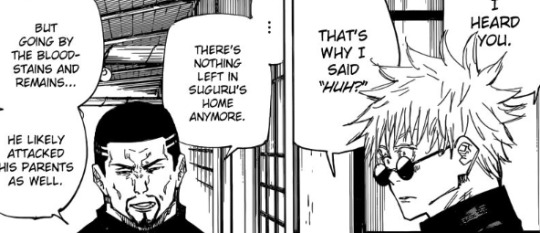

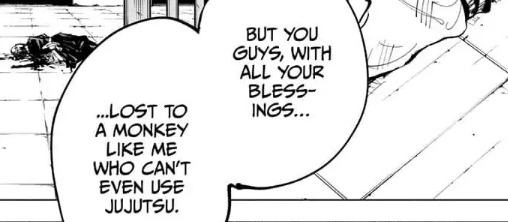

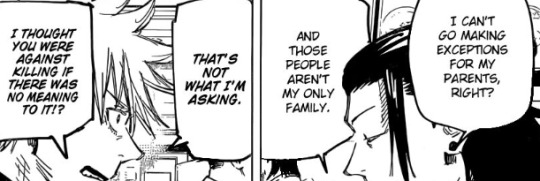

His actions are a rejection of the Jujutsu System as a whole and also a response to trauma. A few of his habits after his radicalization are a direct response to Toji. First, when Toji tells him to be sure to thank his parents, Getou goes out of his way to kill his parents when he switches his side. Also the first character to use the term ‘monkey’ to refer to people who cannot use Jujutsu, was Toji himself immediately after taking out Getou.

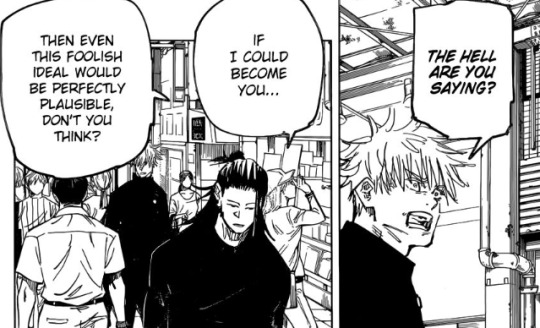

However, while Getou rejects Jujutsu Society he is still someone very much shaped by it. Despite Getou believing in acting for the collective good, he is someone raised with an individualist mindset. He believes power is everything especially when it comes to changing the world.

Getou even says this, if he had the strength to kill every last person on earth, he would use that strength to kill everybody in a heartbeat. Despite the fact that what Gojou wants is to stop the suffering of individual sufferers because he views them as the weaker party compared to the masters, he also reflects a survival of the fittest mindset in his actual methodology. One, he tries to accomplish everything with mere strength alone. Two, he wants to create a world where the only people are allowed to survive are Jujutsu Sorcerers, those born with Jujutsu abilities.

Getou looks down on people who are not born with inherent Jujutsu powers, especially people like Toji the source of his trauma. However, the reason someone like Toji even existed was not because of the fact he was born without any inherent abilities, but rather the way he was treated and looked down upon by everyone because of it. Getou in a way despite trying to reject society reflects many of the prevalent views of that society. Everything should be decided by the strong. People born without Jujutsu abilities are worthless and to be looked down upon. People need to be sacrificed for the greater good of everyone, even innocent people just trying to live their lives. Instead of just sacrificing one Riko, he’s decided to sacrifice millions of Riko’s.

The society Getou wants to produce is a carbon copy of the Jujutsu Society that he came from, he just wants to put a different set of people on the top. This is also something that Gojou points out as a flaw in Getou’s reasoning, yes it’s possible to just slaughter everyone to affect change, but the people in charge are inevitably going to just be replaced by new people if you don’t change the attitudes of the system as well.

Getou wants to make a better world, unaware of how shaped he is by the system he’s reacting to. He judges people on how they were born just like Jujutsu Society, in volume Zero he’s perfectly willing to attack teenagers to get what he wants. (Remember one of his criticisms of society was how many teenage Jujutsu High Students die horrible deaths).

Getou repeats the prejudice that the Zenin family has on Maki, by dismissing her as a monkey for her lack of natural born ability, despite the fact that she’s working harder than anyone else to become a sorcerer.

Once again this is all rooted to the idea of empathy that surrounds Getou’s character. He’s someone who will always sympathize with the individual, in a world where individuals die all the time, and Getou cannot handle that. It drives him insane. His only response to this hyperempathy he experiences is to completely shut that off.

Getou is able to kill his own parents, because he doesn’t see them as his family anymore. His only family are the ones he chooses to see that way. Getou is able to imagine slaughter on a widescale, because he doesn’t see them as human. He doesn’t connect or empathize with their pain in any way. It’s an extremely bad coping mechanism. The world dehumanizes Shamans and in response, Getou dehumanizes the masses. If you don’t see a person as human you don’t have to think about what you’re doing to them. Getou still empathizes with people, but only sorcerers. He spares them because he sees them as human.

In essence Getou is someone who wants to build a more just world, but he’s forgotten about love and connection. He’s turned off the part of his brain that empathizes with the individual and the hurt because if he left it on he’d never be able to accomplish what he wants to do. It’s also the reason the Getou from Hidden Inventory is eventually defeated by the love he had forgotten after staring at the ugliness of the world for too long.

367 notes

·

View notes

Note

About saying Star Wars is Buddhist or Taoist -- I don't believe SW has been created by practicing Buddhists, and the appropriation has absolutely been problematic (there can be white and non-Asian Buddhists because it *is* a proselytized religion, but I don't know of many on the creative team). However, a twitter thread I saw about the subject was written by a South Asian Buddhist who *wanted* more recognition of Buddhist themes. I've also seen Buddhist websites write about TLJ.

Also, lj-writes insisting that SW is about moral dualism while being one of the strongest condemners of TLJ for rejecting moral dualism, doesn’t really add up. IDK their faith but their post ends with “Christianity is good enough!”. TLJ has surface symbols of Buddhism and Taoism AND themes of anti-classism, non-dualism, action returning to the actor, the Middle Way, skillful means, etc. And they see it as a deeply wrong entry in the saga. So it feels like this is lowkey “keep SW Christian”?

Long, long, disgressive answer under cut

About saying Star Wars is Buddhist or Taoist – I don’t believe SW has been created by practicing Buddhists, and the appropriation has absolutely been problematic (there can be white and non-Asian Buddhists because it *is* a proselytized religion, but I don’t know of many on the creative team).

As you said Buddhism is open to all as a religion – and I think it’s also important to note that someone can be interested in the ideas and philosophy without active religious practice, and that’s there nothing wrong with that. I’d actually say it’s good to be interested in other cultures and religions, that it helps to confront the fact that one’s values are not universal (and not ~better or ~superior)

But I also think there is a difference to be drawn between Buddhism, the real thing, and the watered down (for Westerners) new age version of Buddhism

With this established – Star Wars wasn’t created by Buddhists, though among the creatives involved some had a certain appreciation for it: I don’t know about current members of LF and its creatives, but Irvin Kershner studied Zen Buddhism and had an appreciation for the philosophy; Gary Kurtz, who was more involved than most in helping Lucas with the firsts SW drafts, was interested in comparative religion, and Buddhism especially – I think he actually converted. According to himself, Gary Kurtz helped Lucas defining the Force (among other things); but they had a, hum, falling out and it seems Lucas dropped much of what Kurtz had been pushing for afterward (for example, according to Kurtz, he convinced Lucas to drop the Chosen One element in the ANH drafts, but as we know it would be reintroduced).

But then there’s Lucas himself, and we’re gonna enter actually problematic territory. First, Lucas does call himself a Buddhist – well, he calls himself a ~Buddhist Methodist (Methodism being the religion he was brought up in), with such justifications as "that’s what my daughter said when the school asked" (paraphrased) and “I was raised Methodist. Now let’s say I’m spiritual. It’s Marin County. We’re all Buddhists up here” (quoted verbatim). Honestly the Marin County thing I find… The Bay Area and Marin County being a place where so-called “alternative religions” flourish and where new age spiritualism established itself strongly starting in the 60s really doesn’t make everyone there “Buddhist”, thank you very much, and pretending so at the very least betrays a lack of understanding of what Buddhism actually is.

Still, I must note being flippant about the reasons behind one’s religious beliefs is nothing bad in itself! Lucas is under no obligation to disclose these reasons if he doesn’t want to, no more than anyone else.

But looking at Lucas’ understanding of Buddhism, or lack thereof – well, to do that we need to look at Lucas’ views on religions in general, views deeply influenced by Campbell, who was a shitty scholar of comparative religion, and pretty explicit about both having an agenda (the salvation of a modern, Western man alienated by his own modernity), and the fact that he was an adept of the “pick and choose what fits my ideas and ignore the rest”. In fact, as early as his first book, he was anticipating and deflecting methodological criticism in the introduction:

“Perhaps it will be objected that in bringing out the correspondences I have overlooked the differences between the various Oriental and Occidental, modem, ancient, and primitive traditions. The same objection might be brought, however, against any textbook or chart of anatomy, where the physiological variations of race are disregarded in the interest of a basic general understanding of the human physique. There are of course differences between the numerous mythologies and religions of mankind, but this is a book about the similarities; and once these are understood the differences will be found to be much less great than is popularly (and politically) supposed. (Introduction to The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell)

There’d be a lot to say about this passage – it’s not how you answer criticism or justify your methodology. Campbell shows here he’s perfectly aware that his focus on “correspondences” is in itself grounds for criticism. The thing is, in itself focusing on similarities is not “wrong, don’t do that ever” – but in conjunction with the overlooking of differences, it’s a choice that should be explained and justified as an approach for the concerned study. Campbell’s preference for exploring similarities is not inherently bad; it’s the fact (and this is the Cliff notes version) that it’s done in conjunction with a complete disregard for differences, as well as by relying on an ethnocentric framework of interpretation, among other things. Like not justifying his approach – “Once these [similarities] are understood the differences will be found to be much less great blah blah blah” is not a justification, it’s a polite way of saying everyone who doesn’t agree just doesn’t get it.

(And I disgress but like. This book was published in 1949. So when he’s comparing his lack of focus on differences to the lack of focus on “physiological variations of race” in anatomy texts, there is no fucking way he didn’t know what he was referencing, ie the terribad, rooted-in-prejudice physical anthropology of the 19th and early 20th century, and he wrote that after fucking WWII. “There’s no scientific racism in textbooks” is the way he defends giving the flying bird to methodology. I don’t even know what to do with that. Did Campbell thought textbooks should get into “physiological variations of race”? He’s not exactly framing that absence as a good thing, and he’s decontextualizing it, making it sound like an oversight rather than “we tried to take the racism out of the textbooks.” Is he, along with the “it’s political” hint subtly accusing his anticipated detractors of racism, equating the rooted-in-prejudice focus on “physiological variations of race” that was already considered non-scientific when he was writing, to saying differences in myths should be taken into account? In any case it’s a false equivalency. A stunningly bad one.)

Thing is, whether comparative should emphasize similarities or differences is something about which there’s been discourse for years. Nowadays we lean more towards particularism, ie. emphasizing differences. Of course, both approaches have their own pitfalls – the same main pitfall, in truth, which is that focusing exclusively on similarities or on differences erases the true complexity of a phenomenon. But it should be said the current leaning towards particularism has much to do with the uncomfortable admission that much of the thinking behind the emphasizing of similarities was rooted in prejudice:

The problem of the same and the different has become a crucial issue within the field of comparative mythology and for the self-definitions of postmodernism. […] we must acknowledge that the emphasis on likeness, often epitomized by its critics in the same metaphor that James Tate uses to defend it (the metaphor of not seeing in the dark), has done great harm in the history of the study of other peoples’ cultures. Occasionally the metaphor is used to make a positive statement about sameness; thus Francis Bacon, in his essay “The Unity of Religions,” argued positively for the mutual resemblance of religions: “All colors agree in the dark.” Almost always, however, it is pejorative. […] Even without the metaphor of cats or cows in the dark, the assumption that all members of a class are alike has been used in many cultures to demean the sexual or racial Other. (I capitalize Other in the anthropological rather than theological sense, designating people regarded as nonhuman because of their ethnic difference, rather than the deity that is other because of its metaphysical difference.) After all, the essence of prejudice has been defined as the assumption that an unknown individual has all the characteristics of the group to which he or she belongs. “People like you,” or “They’re all alike” is always an offensive phrase. Racism and sexism are alike in their practice of clouding the judgment so that the Other is beneath contempt, or at least beneath recognition; they dehumanize, deindividualize, the racially and sexually Other. […] We speak of racial discrimination, but the myths teach us that the real problem is racial indiscrimination—the unwillingness to discriminate between two different members of another race, the tendency to regard them all as doubles of one another. […] It is this perverse use of the doctrine of sameness, applied to both texts and people, that the comparatist must overcome in order to argue for the very different humanistic uses of the same doctrine. (The Implied Spider, Wendy Doniger)

I may sound harsh on Campbell, but the methodology issue does matter, especially because it comes with an agenda, and because of Campbell’s own influences (and personal politics, however much he liked to pretend being apolitical):

For there is no doubt that the three mythologists [Jung, Eliade, and Campbell] here under consideration have intellectual roots in the same spiritual climate as that in which early fascism and sometimes antiSemitism flourished: Nietzsche, Sorel, Ortega y Gasset, Spengler, Frobenius, Heidegger, the lesser Romanian nationalists and German “volkish” writers and, before his courageous rejection of Nazism and exile, Thomas Mann. Most of these just named were not fullblown partisans of their respective national fascist parties; some, such as Nietzsche, would have condemned political fascism as utterly contrary to the heroic individualism for which they stood. So also, by their own later testimony, did the three mythologists. Yet there is in that climate and the three mythologists an unmistakable common intellectual tone: antimodernism and antirationalism tinged with romanticism and existentialism. This subset of modern thought is deeply suspicious of the larger modern world, as that world was created fundamentally by the Enlightenment (despite, as we shall see, their embracing of some themes, like nationalism and the purifying revolution idea, carried over from the Age of Reason’s turbulent finale). Above all, the romantic antimoderns decried modernity’s exaltation of reason, “materialistic” science, “decadent” democracy dependent on the rootless “mass man” its leveling fosters.

In contrast, they lauded traditional “rooted” peasant culture, including its articulation in myths that came not from writers but from “the people,” and they no less praised the charismatic heroes ancient and modern who allegedly personified that culture’s supreme values. Above all, one felt in these writers a distinctive mood of worldweariness, a sense that all has gone gray—and, just beneath the surface, surging, impatient eagerness for change: for some tremendous spasm, emotional far more than intellectual, based far more on existential choice than on reason, that would recharge the world with color and the blood with vitality. Perhaps a new elite, or a new leader capable of making “great decisions” in the heroic mold of old, would be at the helm. (Ellwood))

(It’s no surprise Campbell loved Star Wars when he finally got to watch it – hero’s journey or not, the resonance with his own ideas is much deeper: the yearning for a lost golden age (the remembered pseudo-democratic Republic) full of culture heroes (the Jedi) now replaced by technological oppression (the Empire); even the ~primitive had their role to play in overcoming that oppressive system, if literally rather than through myths, etc, etc.)

I’ve said before the influence of Campbell’s Hero Journey on SW, especially ANH, has been much overblown, and it has – in part because early on, the early history of SW(/ANH) was itself heavily mythologized as a way to legitimize it as a product of an intellectual approach, a product of high culture rather than low (popular, see Bourdieu) culture. It didn’t come from Lucas at first, but rather from critics trying to explain the success of a movie so deeply steeped in popular tropes and themes – hence the idea that the resonance of the movies, their popular appeal, have been carefully engineered, mapping a pseudo-universal narrative pattern.

So why do Campbell’s views even matter? Because Campbell is a major influence: Lucas rarely mentions anyone that’s not Campbell when he’s talking about his views of religion or mythology. I’ve found Jung here and there (and of course much “[X social science] says…”), and it’s very possible I missed names – there’s a lot of interviews and talks and what-have-you out there. Nonetheless, Campbell is clearly Lucas’ main reference; more than that, he’s a mentor figure. Lucas’ Yoda, as he himself says, and in a sense the man who initiated him. He’s also a ‘precursor’ – the mythicized forefather, the man of erudition whose invocation automatically lends legitimacy to Lucas’ own words on mythology and religion.

For Lucas, all religions relay the same moral values, the same understanding of good and evil. If they don’t seem to (and really they don’t; “good” and “evil” are not universal concepts. They don’t have a one-size-fits-all definition. Different cultures conceptualize and define those terms differently, and not only do those concepts and definitions change with time, but “a culture” is not a monolithic entity in which all members agree on everything either. For terms as loaded as “good” and “evil” -or “bad”, because arguably, not all cultures have a concept of “evil”-, there are a lot of competing definitions with more or less in common), it’s because the observers stop at surface details, missing the underlying truth – meaning anyone who disagrees on this view of religion just doesn’t get it, which is the kind of mindset that leads you to explain to people they don’t understand their own religion. But you, the educated, liberal Westerner (I mean Lucas, who has a high opinion of himself as being, well, an educated liberal dude frequently misunderstood by people less intelligent and less talented than him, and absolutely presents himself an authority on religion, myth, and anthropology, which he is not), you do. It’s a somewhat circular reasoning:

I believe in (x) god/values and that this belief is universal (people may say differently but really, they believe the same things I do, how could they not? They’re good things. The best things!)

Studying other beliefs (by focusing only on similarities and presuming it’s all about my beliefs under the surface) reveals, amazingly enough, that my beliefs are universal. What a surprise amirite.

I have the beliefs I have because they are universal, and since they are universal, they cannot be questioned.

To go back to the specific Buddhism issue, that’s how Lucas approaches it. He doesn’t give a whit about what Buddhism actually is, its values and its philosophy. He doesn’t need to: he already knows that, like every other religion, those values, that philosophy, correspond to his own beliefs. Opinions not needed, because that verisimilarity is only seen by the enlightened.

(Which comes down to erasing people’s actual beliefs across time and space to defend the notion that, conveniently enough, everyone the world over shares Lucas’ christian moral values (or is getting there because it’s the natural end of the processus – which would deserve a few paragraphs in itself because that’s related to the concept of linear cultural progress, another thing rooted in prejudice and shitty, outdated anthropological notions.))

All that to say that Lucas is just about as Buddhist as me (I am not), and that fuck yes we’re in problematic territory, way more problematic than is usually acknowledged. I probably didn’t need to write so much about it (well there’d be more to say, in fact, but that’s quite a bit already); it’s not quite what you asked for but there it is nonetheless.

However, a twitter thread I saw about the subject was written by a South Asian Buddhist who *wanted* more recognition of Buddhist themes. I’ve also seen Buddhist websites write about TLJ.

I think the discussion over Buddhist/Taoist themes in the OT and PT is a different one than the one about these same themes in the ST, simply because it’s not a Lucas product. I absolutely understand wanting more recognition of these themes when they are present, and I think Buddhist themes introduced in the current trilogy can bring about a new interpretation of the… spiritual elements in the story and the universe (arguably already happened), changing how we receive the full saga (I’d even argue that it’s part of what makes SW a modern myth: myths do not care for their author; they spread and grow and change through both social and individual forces. Myths change through their tellers and their audience; it’s how they endure and remain relevant and meaningful. A myth is never just one story – it’s literal and symbolic and full of shadowy spaces that leave room for new, unprecedented readings.)

But that doesn’t change how much Buddhism did or didn’t influence Lucas when he was making his own movies, conceptualizing the universe and its spiritual tenets.

I’d also argue (and that’s something I feel strongly about) that it’s very much possible to apply a Buddhist lens to the text in any case, because doing so doesn’t require for the text to intentionally feature those themes. The author is after all, mostly dead. But I do think there is a difference between “this text can be read through a Buddhist lens, and here’s how” and “this text is Buddhist”.

Also, lj-writes insisting that SW is about moral dualism while being one of the strongest condemners of TLJ for rejecting moral dualism, doesn’t really add up. IDK their faith but their post ends with “Christianity is good enough!”. TLJ has surface symbols of Buddhism and Taoism AND themes of anti-classism, non-dualism, action returning to the actor, the Middle Way, skillful means, etc. And they see it as a deeply wrong entry in the saga. So it feels like this is lowkey “keep SW Christian”?

I found the post I reblogged while doing research for a meta/essay (which I will probably never post) and I only gave a cursory look to the blog, so I don’t quite know OP’s position on TLJ – nor can I speak for them on the way they articulate it all. I understand that you wouldn’t want to ask them directly, but I can’t talk for them either

The way I personally read “Christianity is good enough” (which, for the record, has nothing to do with my own religious beliefs because I’m hardcore atheist) was more of a “there’s no need to pretend SW is stepped in Buddhist/Taoist thought rather than Christian – because there’s really nothing wrong with that in itself”. And really there isn’t. A Christian inspired mythos is just as fine.

(The thing is that often enough, the idea that SW is better for being steeped in Buddhist or Taoist rather than Christian values is not fully unrelated to what I’d call the “Magical Oriental Religion” trope, and I find any attempt to hierarchize religious beliefs deeply dubious and reductive, and also, you know, kind of offensive.)

To conclude – SW is about moral dualism, and it’s not like Lucas never literally said so, have an example:

“The Force evolved out of various developments of character and plot. I wanted a concept of religion based on the premise that there is a God and there is good and evil. I began to distill the essence of all religions into what I thought was a basic idea common to all religions and common to primitive thinking. I wanted to develop something that was nondenominational but still had a kind of religious reality. I believe in God and I believe in right and wrong.” (Lucas, quoted in The Phantom Menace Scrapbook, Ryder Windham, emphasis mine.)

But! We don’t have to read SW as dualist, and most importantly it doesn’t have to keep being written this way (see: TLJ), but that’s not gonna change that it *is* how Lucas conceived it, and that it can hardly be retconned without rejecting Lucas’ definition of the ever-famous balance:

The core of the Force–I mean, you got the dark side, the light side, one is selfless, one is selfish, and you wanna keep them in balance. What happens when you go to the dark side is it goes out of balance and you get really selfish and you forget about everybody…(Clone Wars Writers’ Meeting, 2010, transcription from here (x), emphasis mine)

(This is way too long already, but send me another ask and I’ll get into early ANH drafts and Force Jesus and his apostles, selflessness as sacrifice and the recompense thereof in the afterlife, the rejection of bodily things and pleasure and a bunch of things that make it hard to not see SW (or I guess Lucas’ SW) as deeply steeped in Christian thought)

#i ran circles around your ask#there's just so much to say#and it's not the least complex subject matter either#anon#ask#star wars#george lucas

7 notes

·

View notes