#from now until the 23rd there are exactly six days that i don't have work.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

weh

#i am so busy for the next three weeks and i can't focus on this stupid essay because i don't know what to write#and there are a million other things that feel way more important#but i have to do it! i keep pushing it back w my professor and she will run out of patience eventually!#from now until the 23rd there are exactly six days that i don't have work.#one is tomorrow#one i'm getting my flu shot and booster so that'll suck lmao#one is technically not officially a work day but i will be working.#and i need to get saturday off because i'm moving and forgot to request the time#realizing after doing the math that that sounds like normal weekends. for context my job is deeply irregular w scheduling and the six days#are sporadically strewn over the calendar#like i am working every day wednesday to saturday#getting vaccines on sunday then monday morning setup at 6:30am then going to class then a closing setup ending at 10:30pm#AND THEN 3 STRAIGHT DAYS OF 8-5 TRAININNNNGGGG#IM TIREDDDDD#oh yeah ALSO i;m moving! into a new apartment where it will just be me and the roommate (unknown vibe)who i found on facebook for a few day#until other roommate (affectionate) moves in#SORRY i don't want to stew in negativity too much but it is hard not to spiral looking at my calendar#goodnight :(

1 note

·

View note

Text

Source.

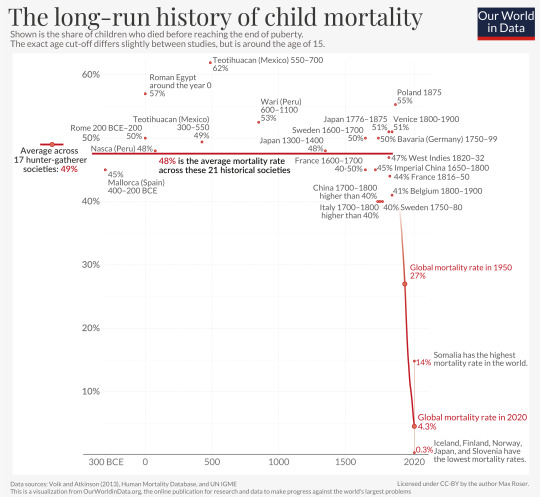

I think about this graph sometimes. Or, rather, I attempt to think about it, and find I can't wrap my head around it. What was it like to live in a world where parents routinely outlived their children? In the world. Until about a hundred years ago, the world where parents routinely outlived their children was the only world that had ever existed.

From Antonia Fraser's The Weaker Vessel, about life for women in 17th-century England:

William Brownlow kept a meticulous recording of [his wife's] child-bearing from 27 June 1626 when their first child Richard was born, who died in October of that year, down to the birth of their nineteenth child twenty-two years later... At one point, between 1638 and 1646, seven children, born at almost exactly yearly intervals, died in a row: Thomas, Francis, Benjamin, George, James, Maria, and Anne. William Brownlow's exclamations of grief as each new tragedy struck show some attempt at reconciliation to the workings of providence -- "Though my children die, the Lord liveth and they exchange but a temporal life for an eternal one" -- but absolutely no diminuition in grief. Little George, his fifteenth child, managed to live from October 1641 to 29 July of the following year; when he died, his father wrote, "I was at ease but Thou O God hast broken me asunder and shaken me to pieces."

Or take the case of Peter the Great, quite possibly the most powerful man on earth for much of his reign: of his fifteen legitimate children, eleven died before their fifth birthday and a twelfth only made it to age six and a half. The chart above has a more expansive definition of "child" (to age 15) and even by its count, Peter the Great and the Brownlows were particularly unlucky. But still.

The other day, at a book sale, I picked up the diaries of Martha Farnsworth, who grew up in Kansas in the 1870s; her only child was born in January 1892 and lived five months. You can read the entries yourselves: January 24th, "The dearest, sweetest little treasure ever a mother had"; April 15th, "I can't thank God enough, for sending this baby into my life"; May 23rd, "My little treasure, don't get sick, for it makes mother's heart ache and ache"; May 31st, "My heart aches with fear"; June 27th, "God sent the angels for her and her terrible suffering ended and mine commenced."

And then I put the book back and went to pick up my kids from school.

And I think now: Martha Farnsworth would trade places with me in a heartbeat. Two children, both of them well past the age of five. One of them missed school today with a cold. I'm not worried. If you zoom out far enough I am in a cohort of the luckiest parents who ever lived.

So why don't I feel my good fortune more?

Part of it, granted, is that constant grateful joy is not necessarily the most useful tool in the parent's toolbox. Sometimes you have to stop thanking God that your children are alive and start pointing out to them that if they're going to borrow your phone then they need to tell you when someone's trying to reach you (for example). But in theory one can correct them, or have activities separate from them, and still think, "Wow, I'm a lucky dog," all the time, because if your kid is alive and healthy and growing then you are a lucky dog all that time.

I want to make a larger sociological statement, about how "X doesn't make us happier," for whatever feature of the modern world X, maybe should have very little value as a criticism. The tenfold decline in child mortality has to be one of the most profound shifts in human history; if we can take that for granted, then there may be no limit to our ability to make lemons out of lemonade. But I can't criticize other people for failing to do what I seem very bad at doing myself.

4 notes

·

View notes