#for example i am so dead serious about agent 4's character

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

see the thign about splatoon is you have to take it deadly seriously and not at all at the same time. it’s a goofy squid game but also your opinions must be the only ones that ever matter. the cephalopods must have 5000 mental illnesses but also they’re just little guys. thats the best way to enjoy it i think

#for example i am so dead serious about agent 4's character#but also i think that they are a little dude who experiences whimsy and joy at a constant rate#splatoon

765 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leon and Survival

Motivations and Guilt as an Agent of Death

The Biohazard universe requires the audience to suspend disbelief, particularly in regards to the protagonists surviving events where others would have died. One could argue that this is merely protagonist armor for the sake of thrills and playing the game, but if you’ll allow me, I’d like to get a little more symbolic and meta about this fact.

Leon is defined most prominently by two things: his tenacity, quick-thinking, and improvisation in the field, and the severity of the loss he experiences when he fails to save people in need. This eventually leads Leon to become the jaded and a little more distrusting version of what he used to be. But what’s most important here is despite this, Leon never loses his penchant for gambling on a snowball’s chance in hell. He never loses his idealism. He never stops believing he can help someone.

If I could let myself be facetious for a moment: Leon S. Kennedy. Leon Sentimental Kennedy. Leon Self-Sacrificing Kennedy. Leon Serve Justice Kennedy. Leon, ever the Survivor.

I have touched on this before in my exploration of Leon’s PTSD, but I really need to stress for anyone and everyone willing to listen: Leon does not take the term “survivor” as a compliment or as something to be lauded, and he prefers not to be referred to as such. At best, he uses it ironically in order to make fatalistic, derisive jabs at himself. The term serves as a reminder of all the people he’s failed and all the innocents he’s lost. This is also why, in Degeneration when defending Claire’s expertise, he omitted the fact that she wasn’t the only Raccoon City survivor in the room.

For Leon, helping others get to safety supersedes everything, including direct orders from top brass on mission; at the root of it, seeing others get out and survive IS his mission. Take, for example:

The important scene in RE2 leading up to and following Robert Kendo’s death, in which Leon shows serious emotional compassion for Kendo’s family and demands that Ada not keep the truth from innocent people. He explains that helping people is the only reason why he’s even here, that he cannot and will not allow her or anyone else keep the truth quiet.

When Leon and Helena are walking through Ivy University and come across the man looking for his daughter. Helena insists that they don’t have time for this, to which Leon responds, “We’re making the time.”

There is nothing more important or valuable to him than another’s life. Therein lies the greatest source of scarring and trauma for Leon: most of the people he stops to help end up dying anyway, and he is left standing over his friends’ and charges’ bodies, asking himself what exactly was the point of it all.

One could argue that this signifies Leon being protected by a force greater than himself. But you could also argue that Leon is that very protective force acting upon others. It is a secondary role, certainly, as his main career and role is to protect and serve and keep others alive. But no less important is this one: in which Leon S. Kennedy assumes the role of a psychopomp in the Biohazard universe.

Greek for “conveyer of the soul,” psychopomps serve a crucial role in most mythologies in that they exist to guide the recently deceased to the afterlife without hitch. It is important to note that many psychopomps do not exist to judge the soul; that they simply guide them to the next stage of passing. They are described as liminal beings: able to pass through both the land of the living and the land of the dead.

Below the read more I will explore these three defining aspects of Leon as a psychopomp. This is already a long post. Take a breather, maybe. Get some water. Get some sleep.

Judgement

One major quality that separates Leon’s character from many of the heroes in the Biohazard universe is that Leon's primary motivation is protecting innocents from villains rather than fighting the villains themselves; his personal stake in this fight is one based on compassion and the need for helping the victims and survivors. He doesn’t waste his time hating the bad guys more so than combating the corruption and greed that they stand for.

It is this nonjudgmental quality about Leon that allows him to see the world in shades of grey. He can empathize with motivations even if he doesn’t agree with them, and it’s for this reason why he can work so easily beside people like Ada Wong, Manuela Hidalgo, and Alexander Kozachenko.

With Leon as a psychopomp, this grey morality works for another reason: that a number of the characters who’ve died and had an impact on Leon all confessed some manner of sin to him before they died. More than that, they all acknowledge Leon in their own way. Below I will list some notable examples:

Marvin Branagh: Arguably the catalyst for Leon accepting his role in this fight, Marvin is first of many people to die in Leon’s line of service to the cause. When the Lieutenant insists that Leon leave without him, Leon refuses and says there’s still time. It is only when Marvin pulls a gun on him to save himself that Leon relents. Marvin names his guilt: “I tried, Leon. But I couldn’t stop it. We can’t let this thing spread. It’s on you now.”

Ada Wong: (subverted) Ada Wong is an entire meta post on her own in regards to Leon’s feelings, but she deserves mention here. The pain of her betrayal, “Why couldn’t you just hand over the sample,” was later exacerbated with the knowledge that she chose (allegedly) to die on her own terms rather than allowing Leon to save her. Ada tells him that “It isn’t worth it. Take care of yourself,” before falling to her supposed death.

Adam Benford: The United States President and long-time friend of Leon’s, Adam was prepared to sink the USA’s reputation into the ground for the sake of the truth and taking responsibility. When he tells Leon this confession, Leon responds with surprise but ultimately with support: “Whatever you decide, sir, I’m with you.” Adam validates Leon and tells him, “I’ve always valued your friendship.” I imagine this is one of the last things he says to Leon before he dies by Leon’s hand.

Luis Sera: Did not intend to die by anyone’s hands, including his own, but his motivations for helping Leon and Ashley are driven entirely by a need to repent. “I am a researcher, hired by Saddler....The sample. Saddler took it. You have to get it back.”

Liminal Beings

Spiritual guides are so powerful in the fact that they have an uncanny ability to travel between both worlds (living and dead) with ease. The most obvious parallel of this is Leon’s sheer luck in getting roped into outbreaks of undead infections and leaving alive and relatively unscathed. Such an existence is a lonely one. While the psychopomp may have companions for a time ( mission partners or innocents in need ), a rare few share his ability to travel between spaces; most often than not, those who follow from one destination must remain behind or move on.

When the psychopomp travels, it is often within a vessel which few can drive or operate, which is undoubtedly symbolic of the soul’s lack of control. In media and story-telling this is actually a trope known as the Afterlife Express. Leon S. Kennedy is often written and played in tandem with vehicular scenes, regardless of whether he is operator, passenger, or witness:

The beginning of Resident Evil 2: In which Leon drives his own Jeep (in full control) and ultimately switches to drive an abandoned RPD police cruiser deeper into Hell; it is subsequently crashed into and destroyed by an oncoming semi. Leon is temporarily trapped in Hell and must survive and find another way out (via the endgame train).

The beginning of Resident Evil 4: In which Leon is being driven by someone else into the countryside Pueblo. He is shown to be gazing out the window, contemplating on prior events. It is a recollection of his life’s past---his---but the ones doomed to meet their deaths are the Spanish police, who up until seemed so deceptively in control of the situation.

RE4: Ada driving the boat to the island. Again, subverted, as Ada does not die but chooses to leave the vehicle on her own terms.This forces Leon to take the controls and steer himself the rest of the way to his next area.

RE4: Mike and the helicopter. He meets and interacts with Leon just long enough to help guide Leon along his path; his death is a subsequent righting of roles. Leon witnessing Mike’s death and promising to honor him posthumously fixes this.

RE6: The start screen and Lanshiang. Leon rides a train with no known conductor steering the rails. The train is empty, save for himself; then with his companion, then with the soul he is sent to fight (Simmons.)

RE6: The plane. The pilot is subsequently killed and mutates into a Lepotica. Because everyone on board, with the exception of Leon and Helena, are infected, Leon is forced to take the controls and land the plane as best he can. Leon crashing the plane and surviving with Helena attests to his ability to move between literal spaces; the corpses and zombies destroyed in the plane crash all move on to the next world.

RE Damnation and the tank: While Sasha drives the tank and steers seemingly to his death against the Tyrant-Class mutant, Leon intervenes.

As a Guide

Beyond everything else that’s been said---and beyond the obvious that Leon’s primary duties are protective detail and getting his charges where they need to go, Leon's presence serves as a reassuring boon to many of the people he comes across.

Leon internalizes the deaths of everyone he fails to save. The main issue with this beyond the way it affects him is that Leon lacks the ability to see the reality of hindsight. Events in which an outbreak occurred (Harvardsville, Tall Oaks, Lanshiang) happened in a large enough scale that containment was nearly impossible. Sterilization was more or less the only way to eradicate the issue at hand. With or without Leon’s self-sacrificing and offers to help, the fact of the matter remains glaringly obvious to anyone else:

Most of the people caught in the chaos of these events likely would’ve died anyway.

Leon stopping to help gave these survivors the chance to last longer than they might have otherwise. He took that snowball’s chance in hell and made it count for what it was worth. The truth of the matter is? Although he is written as psychopomp symbolically, he is first and foremost incredibly and literally human.

From the symbolic, spiritual perspective, Leon is incapable of realizing that it is not his job to stop all of these people from dying---it is simply his job to be there for them so that they are not alone.

#meta.#leon s kennedy#biohazard commentary | ooc.#biohazard#resident evil#long post for ts#tw death#uh.#yeah so this is really long and 'm really proud of it and this is all thanks to luca for their suggestion.#someone tell me I'm good at writing#or someone tell me my love of leon fuckin' kennedy is real.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Salmon Run and Presentation

A (not so) brief dissertation on narrative framing in video games, featuring Splatoon 2

With the holidays in full swing, I took advantage of a deal one day when I went into town, and finally got my hands on Splatoon 2. Having loved the prior game as much as I did, waiting this long to get the sequel felt almost wrong. But like many another fellow meandering corpus of conscious flesh, I am made neither of time nor money.

Finally diving in, I figured I might take this excuse to remember that I write game reviews, sometimes. You know, when the tide is high, the moon blue, and the writer slightly less depressed. I ended up scrapping my first couple drafts, however. You see, a funny thing was happening; I kept veering back into talking about Salmon Run, the new optional game mode the sequel introduces.

Also I might look at the Octo Expansion later, on its own. After I get around to it…

Look, the base game already has a lot of content to explore, and as previously stated, I am sadly corporeal, and not strung together with the metaphysical concept of time itself.

My overall thoughts, however, proved brief, so I’ll try to keep this short.

(Mild spoilers coming along.)

Gameplay wise, I think the story mode is much improved upon by handing you different weapons for certain levels which were specifically built with them in mind. Whereas the prior game left you stuck with a variant of the starter splattershot all the way through. This keeps things interesting, pushes me outside of my comfort zone, and it’s a good way to make sure players will come from a well-informed place when deciding what weapon they want for multiplayer; which, let’s face it, is the real meat of these games and where most players are going to log the most time.

I also love the way bosses are introduced with the heavy drums and rhythmic chants and the dramatic light show. It endows the moment with a fantastic sense of gravitas, and manages to hype me up every time. Then the boss will have an aspect of their design which feels a bit silly or some how rather off, keeping the overall tone heavily grounded in the toony aesthetics the series already established for itself.

Narratively, I felt rather okay about the story aspect of Story Mode. The collectible pages in the levels still have a certain amount of world building, though this time it seems more skewed toward explaining what pop culture looks like in this world, such as, an allusion to this world’s equivalent to Instagram.

Cynical as it is…

That’s definitely still interesting in its own right, though perhaps it’s less of a revelatory gut-punch as slowly piecing it together that the game takes place in the post-apocalypse of Earth itself, and the inklings copied ancient human culture.

We still got some backstory for this game’s idol duo, though. And that, I appreciate. It means Pearl and Marina still feel like a part of this world, rather than seeming obligatory for the sake of familiarity, given the first game had an idol duo as well.

Meanwhile, perhaps it is a bit obvious that Marie’s cousin, Callie, has gone rogue, and that she is the mysterious entity cracking into the radio transmissions between her and Agent 4. If I recall correctly, that was a working theory that came about with the first trailer or two. That, or she had died.

As soon as Marie says aloud she wonders where Callie has gone, I knew right away. And that’s just in the introduction.

That said, on some level, after stomaching through certain other games and such that actively lie or withhold information to force an arbitrary plot twist for plot twist sake, it feels almost nice to go back to a narrative that actually bothers to foreshadow these things. Plus, having gotten already invested in Callie as a character from the first game, I still felt motivated to see the story through to find out why she went rogue. And, loving the Squid Sisters already, there was a hope in me that she could be redeemed, or at least understood. In terms of building off the prior game’s story, Splatoon 2 is moderately decent.

Also, I mean, c’mon. The big narrative drive might be a tad predictable, but hey, this game is for kids. It’s fine.

That, I think, is something I love the most about Splatoon. Despite feeling like you’re playing in a Saturday morning cartoon, and being aimed primarily at children, it doesn’t shy away from fairly heavy subjects. Such as the aforementioned fact that the humans are all long dead and you’re basically playing paintball in the ruins of their consumerist culture.

Which brings me to what fascinates me so much about Splatoon 2: the way in which Salmon Run is framed.

You see, on the surface, Salmon Run appears to be your typical horde mode; a cooperative team (typically comprised of randoms) fights off gaggles of foes as they take turns approaching their base in waves. Pretty standard for online shooters these days, as was modernly popularized by Gears of War 2, and Halo ODST.

I say “modernly,” as the notion of fighting enemies as they approach in waves is not exactly a new concept for mechanical goals within video games. Rather, the term itself, as applied to multiplayer shooters, “horde mode,” became a point of game discussion when Gears of War 2 introduced the new game mode by that same name back in… 2008?

No, no that can’t be right. I played Gears 2 back in high school (I had worse taste back then, okay?). Which, from my perspective, was basically yesterday. That game being ten years old would mean I myself am old now, and that just can’t be. I’m hip. I’m young.

I am, to stay on theme here, fresh.

But okay, existential crises and game talk terms aside, the writing team behind Splatoon 2 probably decided to absolutely flex when it came to the narrative surrounding Salmon Run. It is one of the most gleaming examples of the nontraditional things you can do with writing in video games, to really elevate the experience.

Let me explain.

You see, narrative in video games typically falls into one of two categories: either the story sits comfortably inside of the game, utilizing it like a vehicle to arrive at the destination that is its audience’s waiting eyes and ears. Or the narrative, on some level, exists rather nebulously, primarily to provide something resembling context for why the pixels look the way they do, and why the goals are what they are.

Not to say this is a binary state of existence for game writing; narrative will of course always provide context for characters, should there be any. It’s primarily older, or retro games that give you a pamphlet or brief intro with little in the way of worrying over character motivation, and the deeper philosophical implications of the plot, etc (though not for lack of trying). These would be your classic Mario Bros. and what have you, where the actual game part of the video game is nearly all there is to explore in the overall experience.

Then you have games like Hotline Miami that purposely sets up shop right in the middle to make a meta commentary about the state of game narrative, using the ideological endpoint of violent 80’s era action and revenge-fantasy genre film as inspiration and the starting point to draw comparison between the two. It’s bizarre, and I could drone on about this topic.

But I digress.

Despite falling into that latter category, that is to say having mainly just an introduction to the narrative context so you can get on with playing the game, Salmon Run is a stellar example of how you can make every bit of that context count (even if it does require the added context of the rest of the game, sort of, which I’ll explain, trust me).

First, a (very) brief explanation of how the game itself works, for the maybe three of you who haven’t played it yet.

A team of up to four inklings (and/or octolings) have a small island out in open waters. Salmonid enemies storm the beaches from various angles in waves. Each wave also comes with (at least) one of eight unique boss variants, who all drop three golden eggs upon defeat. Players are tasked with gathering a number of said golden eggs each round, for three rounds, after which their failure or success in doing so shows slow or fast progress towards in-game rewards.

And it’s all an allegory for the poor treatment of labor/workers, utilizing the fishing industry as both an example and a thematically appropriate analogue. Yes, I’m serious.

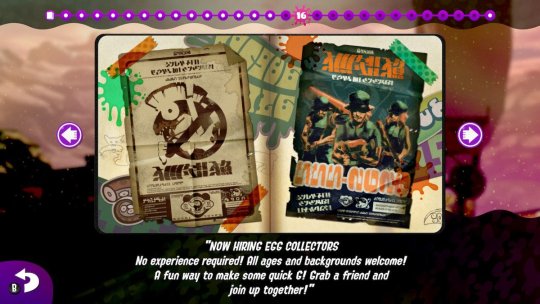

First, Salmon Run is not available through the main doors like the other multiplayer modes. Rather, it is off to the side, down a dingy looking alley. And when you’re shown its location, either because you finally entered the Inkopolis plaza for the first time, or because the mode has entered rotation again, Marina very expressly describes it as a job.

A job you should only do if you are absolutely, desperately hard strapped for cash. You know, the sort of job you turn to if, for one reason or another, you can’t find a better one.

An aside: technically, playing Salmon Run does not automatically net you in-game currency, with which to buy things, as regular multiplayer modes do. Rather, your “pay” is a gauge you fill by playing, which comes with reward drops at certain thresholds; some randomized gacha style capsules, and one specific piece of gear which gets advertised, to incentivize playing.

The capsules themselves drop actual paychecks in the form of aforementioned currency, or meal tickets to get temporary buffs that help you progress in the multiplayer faster via one way or another. Which, hey, you know, that helps you earn more money also. Working to get “paid,” so you can get things you want, though, still works perfectly for the metaphor it creates.

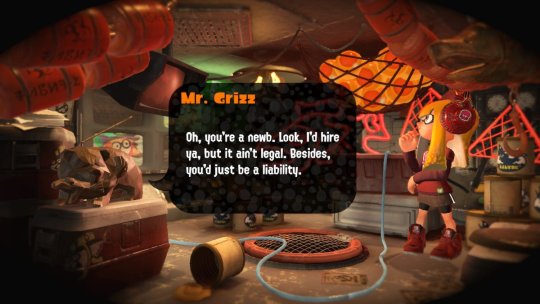

When I first saw it open up for rotation, I found out you had to be at least a level four to participate. Pretty par for the course, considering it’s the same deal with the gear shops. But, again, it’s all in the presentation; Mr. Grizz does not simply say something akin to the usual “you must be this tall to ride.” He says he cannot hire inexperienced inklings such as yourself, because it’s a legal liability.

After returning with three extra levels, I was handed off to basic, on-the-job training. Which is only offered after Mr. Grizz (not ever physically present, mind you, but communicating with you via radio), the head of Grizzco, uses fairly typical hard sell rhetoric when it comes to dangerous, or otherwise undesirable work: calls you kid, talks about shaping the future and making the world a better place, refers to new hires as “fresh young talent,” says you’ll be “a part of something bigger than yourself.” You know, the usual balancing act of flattery, with just the right amount of belittlement.

Whoa, hang on, sorry; just had a bad case of deja vu from when the recruiter that worked with the ROTC back in high school tried to get me to enlist… several times… Guess he saw the hippie glasses and long hair and figured I'd be a gratifying challenge.

The fisher imagery really kicks in when you play. Which, I figure a dev team working out of Japan might have a pretty decent frame of reference for that. A boat whisks you out to sea with your team, and everyone’s given a matching uniform involving a bright orange jumper, and rubber boots and gloves. If you've ever seen the viral video of the fisherman up to his waist in water telling you not to give up, you have a rough idea. Oh, and don't forget your official Grizzco trademark hats.

It’s on the job itself where a lot of what I'm talking about comes up the most; that is to say, despite buttering you up initially, Mr. Grizz shows his true colors pretty quickly. While playing, he seems to only be concerned with egg collecting, even when his employees are actively hurting. This is established and compounded by his dialogue prior to the intermediate training level, in which informs you about the various boss fish.

Before you can do anything remotely risky, even boss salmonid training, Mr. Grizz tells you he has to go over this 338 page workplace health and safety manual with you. But, oops, the new hire boat sounds the horn as you flip to page 1, so he sends you off unprepared. “Let’s just say you’ve read it,” he tells you, insisting that learning by doing is best.

This flagrant disregard employee safety, in the name of met quotas; the fact we never see Mr. Grizz face to face, making him this vague presence that presides over you, evaluating your stressed performance with condescension; that we are not simply given the rewards as we pass thresholds to earn them, having to instead speak with another, unknown npc for our pay… It all drives toward the point so well.

The icing on the cake for me is when a match ends. You, the player, are not asked if you’d like to go back into matchmaking for another fun round of playtime. Rather, you are asked if you would like to “work another shift.”

The pieces all fit so well together. I shouldn’t be surprised that, once a theme is chosen, Splatoon can stick to it like my hand to rubber cement that one time. It has already proven it can do that much for sure. But it’s just so… funny? It’s bitterly, cynically hilarious.

Bless the individual(s) who sat in front of their keyboard, staring at the early script drafts, and asked aloud if they were really about to turn Mr. Grizz into a projection of all the worst aspects of the awful bosses they’ve had to deal with in life. The answer to that question being “yes” has led to some of my favorite writing in a video game.

All of these thoughts, as they started forming in my skull, really began to bubble when I noticed Salmon Run shifts become available during my first Splatfest.

Splatfest is, to try and put it in realistic terms, basically a huge, celebratory sporting event. Participation nets you a free commemorative t-shirt and access to a pumping concert featuring some of the hottest artists currently gracing the Inkopolis charts.

The idea, the notion, that a hip young inkling (or octoling) might miss out on one of the biggest parties of the year because they need money more than they need fun? It’s downright depressing.

It got me thinking. I looked at my fellow egg collectors. In-universe, we were a bunch of teen-to-young-adult aged denizens missing out on all the fun because we desperately needed the cash. We became stressed together, overworked together, yelled at by our boss together. But in those sweetest victories, where we’d far surpassed our quota? We celebrated together.

Spam-crouching, and mashing the taunt, something changed. I felt a greater sense of comradery with these squids and octos than I did in nearly any other coop game. And it’s all thanks to the rhetorical framing of the game mode.

It accomplishes so many things. It’s world building which wholistically immerses you in the setting. But mainly, its dedication to highly specific word choice does exactly what I mentioned earlier: it elevates the experience to one I could really sit down and think about, rather than use to while away the hours, then move on to something else. So many games make horde modes that feel inconsequential like that; it’s just for fun.

There’s nothing wrong with fun being the only mission statement for a game, or an optional mode of play. But this is exactly what I mean when I say this is the nontraditional writing games can do so much more with. And Splatoon 2 saw that opportunity, and took it. And what a fantastic example of bittersweet, cold reality, in this, a bright, colorful game meant mainly for children…

Happy Holidays, everyone!

21 notes

·

View notes