#fantine also projected on Cosette to the point of giving Cosette Everything She Lacked herself

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Overall thoughts on Les Mis BBC

I decided, after all those summaries I made, to write what I hope can be a more coherent opinion on what I thought of the adaptation as a whole. I wanted to make sure to state that my critical reactions weren’t for entertainment purposes only or exaggerated for the fun of it but based on real concerns I’ll expand in this post. This is like the “serious companion”, if you will.

I don’t know if anyone cares about it at this point, but I feel that even though my summaries helped me go through the immediate frustrations in a (mostly) lighthearted way, it’s the distance from having watched it all what gave me a little bit more clarity to order my thoughts.

I’ve established my opinion isn’t worth a damn, I’m not smart or knowledgeable enough for this fandom and, needless to say, these are all my personal opinions, take them with a grain of salt or a bathtub of it. I’m a worthless nobody and my words have no value, but the internet is still (sort of) free, so here I go.

Introduction: the initial news, Andrew Davies & the PR mess

BBC announced the adaptations of 2 media phenomenons which started as books that I love so much I’m considering tattoos of both. And, for both of them, my main concerns were on the person adapting the script.

On the one hand, there’s His Dark Materials, a book series that made me the person I am today, pretty much. One of the directors is none other than Tom Hooper (what are the odds) and the script adaptation was in the hands of Jack Thorne. Cursed Child Jack Thorne. Yeah, not thrilled about that.

Surprisingly enough, His Dark Materials was given a projection of 3 possible seasons, rather than just one, the 3rd hasn’t been yet confirmed but the fact that the script was made thinking on one season per major book on the series, and that each season has 8 episodes planned, at least gives me a bit of hope, even if the person adapting it isn’t in my favorites list.

Les Mis, on the other hand, went to the hands of Andrew Davies, another person I don’t trust.

I’m one of those folk who was never too fond of the ‘95 version of Pride and Prejudice, mainly because of how Darcy was made into a sort of sex symbol, where his flaws were seen as “attractive marks of broody character” rather than vulnerability and with gratuitous sexualizing fanservice. I know a lot of people love it for that and that’s cool, you do you, but it’s not for me.

Then, when he adapted War and Peace, he talked about adding more sex to it and had the Kuragin siblings shown explicitly sleeping together from the get-go in episode 1 and that’s when I stopped watching (there were other things I didn’t like but that one was my limit).

To make matters worse, it made me weary that Les Mis was getting an overall amount of only 6 episodes whereas HDM was getting a potential 24-ish. That was an odd choice.

So, as you can guess, I knew coming in that Davies writing the script, a script with a limited time-frame for the story, was a huge risk.

But, on the other hand, as the cast was announced, I got excited. Especially for people like Archie Madekwe, Turlough Convery, Erin Kellyman and some famous actors like David Oyelowo. Their filming logs on social media, how nice they all were and how much fun they had filming made me happy. I felt that maybe these great folks could turn around whatever the scrip had to disappoint me.

But then came all the PR stuff.

The more I read Davies & co. talking about the show, the less hope I had for it. Talking very badly about the musical and the 2012 movie, calling female characters “not complicated”, insulting Cosette, saying that Javert’s lack of explicit heterosexual sex in the brick was reason enough to push a homosexual narrative centered on an unhealthy behavior, patting themselves on the back for having a diverse cast as if no other adaptation of Les Mis had ever done it before...even their talks about Fantine’s make up made me weary. And, let’s not forget their ridiculous insistence on not having songs.

By the time the show premiered, my hopes had dwindled. The excitement I had upon knowing there would be another Les Mis adaptation so soon, a BBC one at that, and with a cast I had hopes for, was blurred by all the nonsense of PR and I was more afraid than hopeful.

In the end, after having watched it completely, and as you can see for my summaries, I was heavily disappointed. I’ll try to list some of my biggest concerns, in no particular order.

I can’t be super extensive about it, because there are a lot of points to go over, but there are a lot of amazing opinion pieces out there about specific issues, so you don’t need me for that.

Anyway, let’s delve into some of my biggest problems with BBC Les Mis.

Problem #1: The portrayal of femininity

Solely by the fact that Davies stated that women on Les Mis “are not terribly complicated” you know that things are not going to go all too well on that front.

I’m going to pick 3 characters to showcase how badly women were portrayed in this: Fantine, Cosette and Éponine. I’ll leave other characters for another section.

1. Fantine

I’ve talked about Fantine before, upon receiving some questions on my summaries, but I’ll try to explain it all in a more understandable way.

The lens in which Fantine was seen was sexist from the get-go. The way in which the story was framed made the audience complicit in the choices she was making, choices that were negatively regarded by the narrative perspective alone. Her “fall to disgrace” was framed as her own decisions being incorrect, silly mistakes that were easily avoidable, and never regarded as the result of living in a society that was unable to contain her and see her as a valid human being. But we’ll get to that when we talk about the politics (or lack thereof) on this show.

Like I said in my response before, the way in which Fantine is portrayed, even in the musical itself, varies greatly performance to performance. Patti LuPone performing I Dreamed a Dream after Fantine gets dismissed isn’t like Anne Hathaway performing it after she has become a prostitute and neither carry the same implications as Allison Blackwell in the Liesl Tommy’s Dallas modern production, influenced by her experience in apartheid South Africa.

Still, the key element to developing Fantine’s portrayal, when it comes to sexism and the showcasing of her environment, has two layers: the actual oppression showcased in the source material and the contemporary interpretation or lens in which an adaptation will view it.

In this version, Fantine’s character was toned down in her attitude. She was less reactive than in the brick, a lot more passive, a lot more of a tragic figure, which paired up with the fact that this adaptation covered her entire “fall to ruin”, from meeting Tholomyès onward, made her a victim of everything that happened to her.

A victim of her own bad decisions, though, not of a social context that was failing her.

But the worst part is in how the focus of the show is placed. You can have Fantine being a summarized version of herself, with less spunk, and still showcase through her that the circumstances she was in were permeated by an escalating force of social disadvantage and oppression.

This adaptation made, like I said, the audience complicit in Fantine’s decisions as if she was a princess in a movie, unaware of the threats she was getting herself into by her own naive foolishness.

Tholomyès is blatantly shady, clearly dishonest, not at all charming or in any way trustworthy and Fantine gets a “voice of reason” on a friend who tells her various times that he will eventually leave. There are a lot of red flags, blatant for the audience, that Fantine chooses to dismiss. The show focuses less on why Fantine trusted Tholomyès and more on her making a clear bad choice we all knew was doomed from the start.

This becomes a problem once again when she chooses to leave Cosette with the Thénardiers. They are very clearly shady, very blatantly aggressive and ready to take advantage of her, visibly manhandling Cosette in front of her and asking for more money on the spot, and Fantine again naively ignores all of this.

They do it again when she enters employment in Montreuil. She talks to Valjean himself in this version, and is asked repeatedly and with kindness if she has a family. The scene makes it seem as if she could have easily told the truth, especially because we were previously given a scene in which Fantine hears a speech talking about how Valjean is the Best Person Ever and could potentially help her. Still, she chooses to repeatedly lie and the show makes it seem less for necessity and more for a sense of pride of some sort.

(Also, as a foreshadowing of creepy Valjean to come, there are some insinuations from her co-workers that she could seduce Valjean, which is confusingly placed and awkwardly added where it is.)

Then, after she’s dismissed, there’s a man in a post office who asks her, after receiving letters from the Thénardiers (to which she reacts a lot more passively than in the brick), why she doesn’t bring Cosette to live with her, in a condescending tone, as if he was stating the obvious. Fantine responds again as if she was doing it out of pride. The same man is the one to suggest her to start selling her body and then tell her she should have done it before selling her hair and teeth because “nobody would pay for her after that”.

Every turn we’re met with ways in which Fantine’s decisions are seen as foolish in the eyes of the viewer. It’s like Blue’s Clues or Dora the Explorer when they ask stuff to the audience for the kids to say they shouldn’t do something. It’s patronizing as fuck, is what it is. And, yes, sexist.

These narrative choices are sexist because they erase most of the social and political situation which made Fantine vulnerable in the first place, to push the tragic drama as if she was a victim of being “too naive”. It’s sexist because it makes the audience know from the get go that what Fantine is doing is a “bad choice”, easily avoidable mistakes that whoever writes is smart enough to sense are bad but poor naive Fantine can’t understand.

It isn’t just that she’s called a whore a lot of times, that she’s smashed against walls and the ground hard enough that Lily Collins was actually hurt, that she’s shown explicitly being used by a patron on the street. It’s that all of it is done with the added layer of her having “chosen wrong”. That everything is framed as the consequences of actions that the narrative voice, as well as the audience, are smart enough to know are wrong, but poor little Fantine can’t handle.

Like many things in this adaptation we’ll see later, Fantine’s journey is framed more like the tragic end of a woman who didn’t know how to choose right and was punished for said choices rather than the result of an unfair society which didn’t allow women any freedom to choose and didn’t see them as worthy human beings.

2. Cosette

When Andrew Davies called Cosette a “pretty nauseating character” in need of change, I knew I was up against one of those people.

Cosette is probably one of the most underestimated female characters in literature, and adaptations tend to do her dirty very often. I’m not even fond of her interpretation in the musical all that much, which goes in tow with the interpretation of Éponine. I’ve seen my fair share of men on youtube claiming Gavroche should be the face of Les Mis rather than Cosette, I’ve received my fair amount of messages claiming she’s The Worst, I’ve seen it all.

This adaptation does with Cosette something that, out of context, I would have thought impossible. They manage to somehow attempt to make her more “active” (they would call it “strong” but I have problems with that denomination) while making her even more of a helpless victim. It’s a pretty impressive oxymoron.

Let’s begin with little Cosette.

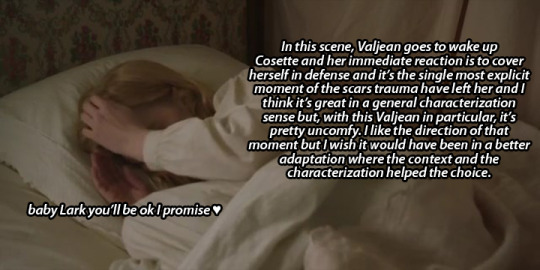

This adaptation does something very weird in that it only showcases Cosette’s storyline as a child when it serves other characters, but then intends to build upon the abuse by mentioning it or making it clear that adult Cosette remembers it well.

So we see Cosette when she’s important to Fantine’s storyline, the Thénardiers’s storyline or Valjean’s storyline, but not much about her on her own, aside from one time she’s looking at dolls and another time when she’s being beaten up by Madame Thénardier, which could be also a moment for the Thénardiers and not solely for Cosette’s narrative.

What I mean with this is that the view on her is reduced to a side character rather than a main one and, with that, her perspective on her own abuse isn’t taken into account. You don’t know how Cosette feels about things, you don’t see her perspective on it, you only see what others do to her but never get to see her side of it. For all the musical erases of her narrative, at least they give her Castle on a Cloud.

It’s with little Cosette where we start to see this weird sense of sexually charged perception towards her relationship with Valjean.

For some inexplicable and highly alarming reason, it’s implied by various witnesses in different occasions that Valjean’s intentions with Cosette may be inappropriate, and I would have let it slide as just people thinking The Worst out of living in a social context in which The Worst is most often the truth, hadn’t that perception carried throughout the series and mixed with Valjean’s erratic and possessive characterization.

When Cosette grows up, she gains a bit more focus, but she also starts to be charged a lot more sexually.

Both Cosette and Éponine are sexualized and objectivized in this adaptation. This will be addressed later, but most often than not this sexualization acts as an accessory to a narrative about masculinity.

Cosette’s virtue, beauty and body are talked about and even exposed in various moments. They tell her she can’t be a nun because that would be “a waste of her beauty”. In that dreadful scene in the dress shop I talked about in summary 4, the shop assistant again implies that Cosette is Valjean’s lover and lets him see her in undergarments through the curtain, with clear intentions. Valjean’s erratic persona is intent on separating her from Marius, explicitly telling her he’s worried that she will be taken advantage of by men, bringing up Fantine’s history to her with that in mind, while putting her in danger and in the company of the Thénardiers again, in more than one occasion.

Adult Cosette has visible signs of the trauma she suffered, which is an interesting direction to go. I haven’t seen an adaptation taking such a big route on her remembering her past abuse, and is a change that worked in performance, Ellie did some great visible responses like covering herself when Valjean wakes her up or going fight or flight every time she sees Thénardier. She is visibly upset when Marius gives him money and looks both angry yet still hesitant when she sees the man for the last time.

But all that kind of loses its importance when the men around her not only don’t give a shit but also do their worst.

Valjean manhandles her, harms her even, pushes her to the limits of her emotional state by taking her to see the prisoners intentionally after she mentioned prison, acting more possessive than caring and more erratically violent than conflicted and concerned.

Marius has a somewhat wet dream about her and then again dreams with her in confusing ways when he’s out of the barricade, with his grandfather talking about her as if she’s a piece of meat even after he meets her and she’s right in front of him.

They tried to make Cosette more aggressive, I think, more reactive, which in some moments worked. But when the lens in which she’s viewed is objectivizing, when she’s being commented on, offered and treated as an object, then it isn’t enough. It makes it worse, actually.

I’m sorry for Ellie, though, she did good.

3. Éponine

Much like Cosette, Éponine’s childhood was all but a few cameos. It’s very often that adaptations try to “tone down” Éponine in order to pull a narrative of her as an underdog in a love triangle, the “friendzoned” girl who tragically dies. The musical does that, for example.

Some of Éponine’s most controversial actions in the brick tend to be most often deleted or changed, except for adaptations in which she’s an “enemy” to Cosette’s narrative of a classic heroine.

It isn’t easy to find adaptations that are able to make Éponine showcase the complexity of her canon character not as a problem but as what makes her character so good and important in the overall story. Hey, even fandom sometimes tends to romanticize Éponine as if she had to be “redeemed” in order to be seen as a worthy character (but that happens a lot with female characters in general).

Éponine doesn’t exist for Marius’s narrative, as the other girl in a love triangle, or for Cosette’s narrative, as an enemy, she’s her own character with her own reason for existing and complex human dynamics that are extremely permeated by the social circumstances she’s immersed in and represents.

I’d say this adaptation is on the group that uses her for Marius’s storyline.

Added to that, it’s one of the worst I’ve seen on that case, because in this one, Marius is complicit of Éponine’s intentions, which are sexualized to a degree I don’t feel comfortable with.

We’ll talk a bit more about the Marius side of things later, but for Éponine, it meant she was reduced to a character that exists to sexually awaken Marius rather than a tragic figure on her own or even a piece of a love triangle. So, basically, this is the worst I’ve seen in a while.

This is clearly seen in that interview when Davies explained why he added that “wet dream” scene, saying:

“One of the best things Hugo does is to have Eponine tease Marius with her sexiness because he is a bit of a prig. So I have introduced a scene where Marius, even though he is in love with Cosette, has a wet dream about Eponine and feels rather guilty about it. I think it fits into the psychology of the book.” Source

Let’s leave out the part where he considers that to be “one of the best things Hugo does” because I cannot deal with that right now. Let’s focus on the other bit.

Like this quote suggests and I said before, Éponine was rather reduced to a tool for Marius’s sexual awakening. In this version, it isn’t only the “wet dream” which precedes more crucial interactions between Marius and Éponine, there’s also a scene where she strips for him through the hole in the wall and another where Courfeyrac is commenting on her and Azelma as Marius moves into the building for the first time.

By the time Marius gives her his money and any sort of bond can occur, it’s evidently clear in this version that Éponine has been teasing Marius and he is fully aware of it. He looks at her through the peep hole licking his lips and then has that disturbing dream where she’s kind of forcing him onto her in a very questionable way.

So, this Marius is by no means unaware of the fact that Éponine was attracted to him in some capacity and has played along her seduction, which makes his dismissal of her and his request for her to find Cosette a lot like he is using her for his own gain and replacing her for another girl.

Éponine’s attitude, much like Cosette’s, tries to be more active at times. She’s confrontational to her parents, seems protective of Azelma and is pleased to see her mother stuck in jail.

However, much like with Cosette, any kind of agency is compromised for having her narrative be serving a male character’s development rather than her own. Her involvement in the barricade is also somewhat modified but, by that time, her journey has already been substantially affected.

Much like Ellie, Erin was a very good Éponine when she was allowed to perform at her best and I wish she had been involved in an adaptation that was able to portray Éponine with more justice.

I’ll talk a bit more about women on the show in general in problem #3 but, for now, let’s move on.

Problem #2: The portrayal of masculinity

1. Javert

I am not the best person to write an essay on Javert, there are a lot of people more capable than me for that, and I may be called out for this and mess everything up, but I can’t write overall opinions without mentioning my issues with his characterization, at least summarized.

Javert is a complicated character. He is, as much as everyone else, affected by the circumstances and a man who goes through a huge emotional impact and sees his values questioned and compromised. His and Valjean’s journeys have a lot in common, in different ways and with different outcomes.

Sadly, Javert tends to be seen as a villain in a lot of adaptations. It’s a way to simplify the plot in the way movies tend to do: something is defined by what the other isn’t, if Valjean is the protagonist, then Javert must be his antagonist. I was worried that this version was going to fall into that trap, because of time restraint and Davies’s tendencies of simplifying complex characters.

Javert’s characterization was erratic, much like Valjean’s. His attitude was blurred by fits of rage and moments of confusing violence, followed by charged pauses in strange cadences which tended to fluctuate. I don’t think his attitude was as all-over-the-place as Valjean’s, but it was certainly not as well defined as other Javerts I’ve seen through the years.

This Javert, however, had a choice made for him that separates him from other versions:

Over tea in central London, Davies tells me that he was surprised to discover that, in Hugo’s 1862 novel, neither character [Javert or Valjean] mentions any sort of sexual experience, leaving the 82-year-old screenwriter wondering, at least in the case of Javert, whether it was indicative of a latent homosexuality. Source

There is a lot to unpack there.

First, there’s this idea of masculinity in which the lack of explicit heterosexual intercourse in canon is directly representative of homosexuality. I’m not gonna delve a lot in the brick but there are a good bunch of characters you can easily read as gay. Hell, there’s that whole thing going on with comparing Enjolras and Grantaire to greek couples. And if you want to write Javert as gay, go ahead, there’s a lot of fanfiction out there who is with you on that and I’m here for all interpretations, no problem at all.

But if you’re going to take that route, you need to be careful with your optics.

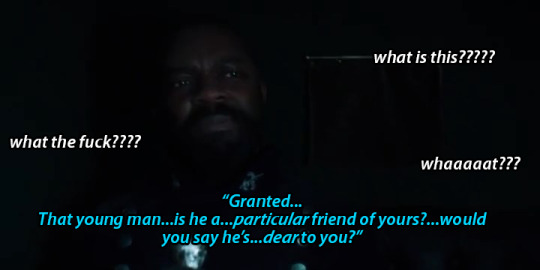

This Javert is, at the end of the day, in this adaptation, a gay man of color. He is also explicitly obsessed with Valjean in a way that exceeds his sense of justice. He looks at him undress in prison, is all over his personal space while he’s in chains and later interrogates him believing Marius is his lover, clearly attempting Valjean to confess to him if he was. He receives a lot of comments from an officer who touches him and looks at him strangely in the last episode, prompting an immediate rejection from him.

Everything points to Javert’s homosexuality being in the plot only as a further motivator for his need to capture Valjean, which makes for both a problematic portrayal of predatory homosexuality and a subsequent narrative of police abuse, both very problematic aspects to portray through a gay man of color. The way he acts and the way in which people act around him make it seem like his obsession with capturing him is fueled by the fact that Valjean represents his closeted feelings and that is all kinds of messed up.

He is also clearly not as involved in other aspects of the law as he is in capturing Valjean, since Thénardier ends up being a secondary worry to him, even explicitly knowing he has been mistreating and abusing a child, and he also explicitly doesn’t care about his achievements or the ones of his other officers as long as Valjean is on the loose. He lets Thénardier escape prison on his watch and doesn’t take care of it himself, prioritizing Valjean.

It isn’t about what happens in canon or not but in how all of this, in this version, is framed under this idea that Javert is also gay and has an obsession with Valjean that seems predatory in part, rather than fueled by his beliefs. And that is a dangerous optic to write a gay character under. Especially a police officer who is also a man of color.

I’m not the one to talk about that, it’s not my experience to tell and I’m not going to speak over those whose experience this is, but as a content creator, I’d question if my need to diversify is stepping over the lines of problematic aspects that may ill represent the identities I’m trying to integrate. Just saying.

David’s performance hits some very good moments, especially when Javert starts contemplating suicide. That is a very important scene in every adaptation and a very amazing chapter in canon and David does well in performing the turmoil in Javert’s decision. They also add, as a voice in off, the notes he left to improve the service, which is a great touch.

But, much like the other characters I mentioned, his performance is blurred by these writing choices in which Javert has been added this sort of predatory sense in which Valjean in jail symbolizes also keeping his identity hidden away. Davies would probably say his “desires” because that’s the kind of guy he is.

I hope my opinion isn’t overstepping anyone’s voice and I’ll leave the further of this discussion to someone more appropriate, but I felt it was an important matter to include and something we all, as media consumers, must pay attention to.

2. Marius

I had higher hopes for this boy, I really did.

The good thing this adaptation does for Marius is give him a bit more room than others do. They touch more on his relationship with his father and his grandfather, they bring up the Thénardier connection to his dad, they introduce Mabeuf, and they bring him on as a kid in the beginning, which even though questionable in comparison to him having more development as a child than Cosette and Éponine, at least helped to introduce him as another key character of the whole story.

I had hopes that this earlier introduction, albeit unfairly unbalanced with Cosette’s and Éponine’s, would allow for his character to develop more strongly, especially since politics were very present in his conversations with his grandfather and the ideals of his dad. I thought that by introducing politics through Marius that would allow his connection to Les Amis de l’ABC be more profound when the moment for revolution came.

Yeah, no, that didn’t happen.

Les Mis is a book where people are the heart and soul of it. With that in mind, characters aren’t like each other, they aren’t repetitions of the other’s attitude, they are diverse reflections of the complexity of humanity. The portrayal of masculinity in characters like Javert, Valjean, Gavroche or each individual member of Les Amis aren’t the same between each other, and neither are the same as Marius’s.

Marius represents a very wide emotional spectrum. He’s sensitive and vulnerable, passionate and driven, but at the same time can take action into his own hands when he has to and fight, even at the cost of his own life. There are layers in Marius. Like a Rogel cake.

I don’t want to generalize but a problem I have often with older male writers is that they see emotional complexity as weakness, especially when it comes to the portrayal of masculinity. There’s this idea in which something that is undefined or conflicting isn’t “strong” enough and therefore requires forcing.

Remember that quote I brought up for Éponine’s characterization? we’re going back to that. To Davies calling Marius “a prig” in need of being seduced.

Like I said, this version made Marius complicit in Éponine’s advances and aware of her sexually charged intentions, and this was made in an attempt to “upgrade” Marius’s masculinity and make him “less of a prig”. Because in order to be a Man, Marius needs to objectivize women. Apparently.

Like I mentioned, the gesture of Marius giving Éponine the little money he had ended up being a lot less effective by the fact that he had already fantasized about her more than once, and with her knowing that. He is taken to a brothel by Courfeyrac and Grantaire in which women pretty much throw themselves at him while he looks for Cosette. The “wet dream” he has is a very eerie combination of idealization and assault, in which Éponine, taking Cosette’s place, forces him onto her (much like Davies is forcing this onto Marius).

It isn’t about sex or eroticism being introduced to Marius’s storyline, is that they appear forced and almost violently thrust upon him in order to validate him in this idea of masculinity the adaptation seems to have, which seems to be very narrow.

And, with that in mind, we’ll move on to the last bit of this section.

3. Valjean

I am unable to write a piece about how many layers of wrong this Valjean embodied.

There are a lot of good tumblr scholars and Les Mis experts talking about it already, they can explain better than I ever could, but we need to, at least, try to glimpse at the mess this was, because this is a post on problems and this was a major one.

There are a lot of interpretations of Valjean, some of which are astronomically awful. He’s a character that can be easily fucked up, maybe because he also represents a very complex range of emotions, a very wide spectrum of masculinity, and is inserted in a wide variety of social contexts and spheres during his lifetime, which permeate his way of living as well as his agency to do things.

Any adaptation of Les Mis from the get go starts with the challenge of representing all of this in a limited time frame and with a limited perspective. It’s very difficult to translate not only all of this complexity but also all the thoughts the narrator can rely, all the feelings and conflicts and internal turmoil that we can get from the book because it’s written.

The musical, in that sense, has some elements from its medium that help, like the soliloquies, the changes of key, the ability for characters to bear their souls through song without interrupting the believability of the story.

Representing Valjean without a medium that allows a peek inside his head is a big challenge. He is a character whose turmoil is most often interior, so showcasing that externally poses difficulty.

Still, you can’t fuck up this much, my dude.

I’ve seen bad Valjeans in my life, this one is...complicated. He’s not good, don’t get me wrong, but he isn’t as clear-cut godawful as others I’ve seen, he’s too erratic to be easily described.

I think this adaptation tried to showcase complexity through visible emotional distress and physical violence. Instead of having a soliloquy or symbolism, we have Valjean shouting or screaming or burning his hand with a coin and staring at it for a while or shouting at nuns or carrying Cosette by force so hard her arm is in pain.

Everything gets even more confusing when everyone around him treats him weirdly.

You get years of exposition clumsily thrown at you via a speech Fantine hears when she arrives at Montreuil and he’s been elected. You get girls looking at him naughtily and suggesting Fantine to try to seduce him. You get inkeepers and Thénardier suggesting his intentions with child Cosette aren’t appropriate. You get women in dress shops thinking his intentions with young adult Cosette aren’t appropriate. You get Javert thinking his intentions with Marius aren’t appropriate. Everyone wants to talk about Valjean’s sex life or something, I don’t know.

His attitude towards Cosette is also muddled by this erratic behavior and the very strange way in which he sees her and Fantine.

He is visibly more worried about men taking advantage of her, of “defiling” her, than other dangers she could be in, like his identity being found out by the police or her falling in the hands of the Thénardiers again. He forcibly removes her from Marius’s presence and has a fight with her about it that ends on him taking her to see the prisoners. He knows she still, as an adult, visibly flinches when she’s approached harshly yet manhandles her when he wants to keep her locked up.

There’s something possessive about this Valjean that ties in to how Cosette is portrayed as an object. He talks about Cosette as if she was something he needs to keep, says Marius will “rob” her, not because he wants to be a good father or see her happy but because she is his to have.

This Valjean feels as if Cosette was his attempt to get rid of the guilt he feels for having failed Fantine more so than anything else. She’s less of a person and more an object he needs to keep for himself like a third candlestick. That’s the impression I got of their relationship with his characterization.

By the time the series ended, I felt upset with Valjean.

I didn’t care if he died, I didn’t care if he suffered. And that’s pretty shitty for a Les Mis adaptation to prompt. He made me feel uncomfortable, uneasy, as if he was the last person I would trust to take care of a young girl. And whatever internal journey he was going on wasn’t developed well enough to understand any of these choices.

I don’t know, like I said, I’m not an expert of the subject of Jean Valjean, but I’m pretty sure this is not how you adapt him.

Problem #3: Diversity without optics

This show hadn’t even started and it was already patting itself on the back for being diverse.

Now, if you haven’t been in the world of Les Mis for too long, let me tell you there are a lot of adaptations which are diverse, and not only of the musical. In itself, it wasn’t a pioneer move, but I was nonetheless happy that they were going to pay attention to that. At the end of the day, Les Mis is about society, about oppression, and adaptations of it should represent the diversity of the social landscape of the time and place they’re created in.

That being said, diversity in a highly political storyline needs to be carefully worked through, because without optics you can make questionable choices. And, you guessed it, questionable choices were made here.

I can’t and won’t go over all of the issues with this that there are, but I can give a few examples.

There is, of course, the always present argument of casting Fantine and Cosette white and the majority of the Thénardiers and Éponine as poc. And of casting the majority of Les Amis as white and the majority or most visible part of Patron Minette as poc. People have discussed this at length so I won’t go over that.

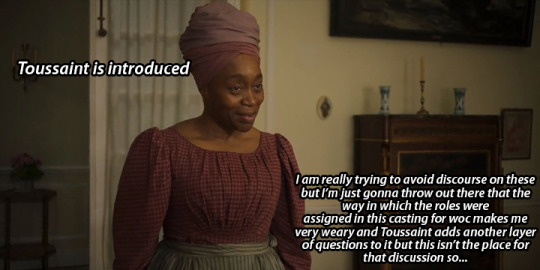

There is also how constantly woc were cast in roles of service, some of which were questionable given the context. Simplice, for example, is cast this way, which I overlooked at the time but as it kept escalating with other characters like Matelote and eventually Toussaint, it grew a bit more complex.

Toussaint was...a very problematic choice.

When you present the character of a “housekeeper” in a period series which is meant to represent France in the 1800s, and she is a woman of color, some alarms start ringing. I don’t specialize in French history, but my instincts were proven correct when I checked various sources on dates, after seeing the episode, and I’m quoting wiki for easier access here:

Slavery was first abolished by the French Republic in 1794, but Napoleon revoked that decree in 1802. In 1815, the Republic abolished the slave trade but the decree did not come into effect until 1826. France re-abolished slavery in her colonies in 1848 with a general and unconditional emancipation.

This series has a weirdly set timeline in comparison to the book but, for all intents and purposes, we’re in the early 1830s at the time she’s first introduced, correct? There was still an unstable situation regarding abolition at the time. The general emancipation hadn’t been yet stated in the colonies and the decree had just been starting to hold effect.

I know this show is casting in a general way as a suspension of disbelief of some historical facts and I’m all for diversity in casting in period dramas, regardless of anything else, if it’s allowing for representation in media.

But, at the same time, you need to be careful with your optics. She could have been cast as anyone else.

I don’t wanna go over this a lot because I don’t know enough about these parts of French history nor is it my story to tell, but the problem is in the erasure of conflicts or racism altogether as a way to prompt a shallow sense of diversity in a story that is directly linked with the subject of oppression.

Let’s continue with another similar optics problem involving “diversity” to exemplify this issue further, so that I can clarify.

This barricade had women on it and didn’t have Combeferre.

Now, here is the thing about that. In the barricade my man Combeferre gives an amazing speech about women and children.

In case you weren’t aware, the 1800s were the moment when European women and children barely started to be seen as separate members of society and not only “men but worse” and “men but small”. There are a lot of good articles about that, including one by Martyn Lyons about the new readers of the 19th Century, which changed the course of the editorial market, those being women, children and working class men, who didn’t have access to literature or literacy before that. The idea of childhood as we know it started then, and the later editions of the Grimm fairy tales was one of the first published books of fairy tales explicitly aimed at children’s education. And since a lot of us, in other places of the world that aren’t Europe, were colonized af or barely getting free from colonial governments in the 1800s, we kinda had to go with the flow, regardless of the social structure of native peoples, because colonialism sucks.

But you all came here for Les Mis so, let’s get back to that.

As this terrible and summarized dive into history implies, women and children were vulnerable to the fucked up state of social strife. Education was scarce and only accessible to some, employment was scarce and only accessible to some, food was scarce and only accessible to some. Most often than not, “some” did not include women and children.

In comes the the sun to my moon, Combeferre, with his speech.

He talks about all of this. Basically he talks to men who are the main providers of families, providers of women and children who depend on them and goes (I’ll paraphrase) “it’s our fault as a society that women can’t be here now, it’s our fault they don’t have the same possibilities and education we do, so at least do them a solid and don’t die today here if they depend on you to live, because the only possibility they have without your support is prostitution”. It was a fucking power move to include that on Les Mis. I mean, the entire book is a call out to the social and political situation, but damn.

So yes, there aren’t women there but the reason for it is that patriarchy sucks and the consequences would be disastrous for them.

Davies & co. pretty much didn’t give a shit about this. But, at this point, considering Problem #1, who’s surprised.

They removed Combeferre, his speech and placed random women on the barricade, as if nothing of that was going on and the patriarchy didn’t exist. Because ~diversity~.

The fact that they thought more woke to put some random women there on the barricade to die fighting instead of acknowledging the existence of sexism altogether pretty much sums up what this whole show thought diversity was.

For them, diversity wasn’t a political and social standpoint born from reality, a way to represent the dynamics of oppression that are at stake even on this day, but an aesthetic.

And, talking about speeches, let’s move on to the next bit.

Problem #4: Where are the politics?

1. The social and political landscape

Les Mis adaptations have a fluctuating balance with politics and social conflicts.

That is, at the end of the day, the very core of the existence of this story, the reason why still, to this very day, it is relevant and quoted, adapted and regarded is the fact that we still need it.

All of us, as human beings living as members of society, are always immersed in political decisions. It’s not only unavoidable, it’s part of our lives as people living together.

In the same way, the personal narratives of the characters of Les Mis are intrinsically linked to this landscape. They are set in different places of the social spectrum and hold different power dynamics and actions that relate to political standpoints.

Adaptations tend to work this in very different ways.

Some focus less on the politics and more on the social strife, with a greater focus on the characters. Others re-insert the characters in other different historical moments with the same levels of social and political strife. Others just copy-paste the situations and put them in another context, without really explaining what revolution it is, what they’re fighting for and why they’re being killed. The focus varies.

It seems, for how this adaptation starts, with Waterloo and a subsequent argument between Gillenormand and Baron Pontmercy about Napoleon, that politics are going to be important. This doesn’t last very long.

My biggest issue with the introduction of these circumstances is that they don’t bother on them but then attempt to use them for gratuitous self righteousness. It isn’t that they abandon them altogether, they overlook them but then attempt to use them for shock value.

There is a constant use of exaggerated, almost cartoon-y, stagings of social depiction:

- You have Gillenormand dining with his boys, in a luxurious and incredibly flamboyant scenery, while dissing political views in an almost comical fashion

- You have beggars downright assaulting Valjean and Cosette on the street right outside the convent, as a means of shock to Cosette’s expectations of the world outside of it

- You have Fantine’s entire sequences as a prostitute with higher and higher degrees of abuse

- You have the streets before the barricades, in some sort of confusing clamor that loses focus in favor of Valjean’s storyline

- You have a god awful last scene which attempts to say something socially compromising by showcasing the kids Gavroche was helping (I don’t think they’re siblings in this version), as a means to say “the revolution wasn’t successful and social strife will always continue” I guess, I don’t know, because it’s not like they gave a shit about it all before, so this kind of Perrault-ish moral of the story at the end makes no goddamn sense

They are exaggerated snippets of things without context, with very little exposition, that are used more as props to shock than they are to actually take a stand on what the original story is trying to tell.

Even the reality Fantine has to suffer is blurred by the fact that the social situation isn’t seen as much as a reality in itself but a combination of Fantine’s “choices” and Valjean’s “guilt”.

But, in order to delve more into the non-political aspect of this adaptation, let’s focus on some specific characters.

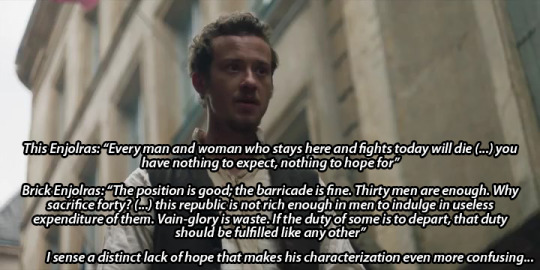

2. Enjolras

Well, I’ve seen a lot of Enjolrai in my life (is that be the plural of Enjolras? yes? no? can it be?).

Enjolras has very different characterizations, even within fandom itself, but we can all agree that he’s a) highly political, b) highly committed to the cause and c) extremely charismatic.

And when I say “charismatic” I mean it in the sense that his speeches are so beautifully crafted, so certain and commanding, that you just wanna listen to what he has to say, regardless of your views. They’re political discourse but also very poetic, which is a very interesting literary opposite to Grantaire’s voice, but I digress.

Still, Enjolras doesn’t stand on his own.

He represents a part of a whole, an important part, but a part nonetheless. Les Amis are a very diverse mixture of individuals, and the main triumvirate represents different stances on the same political action that coexist together.

Without others to stand with, Enjolras loses context. Not because he can’t support himself as a character, but because his biggest value is within other people.

This Enjolras is confusing, angry and loses a lot of steam when most of the people who should be around him aren’t really paying attention.

Courfeyrac, although performed really well, doesn’t really get a chance to show his political ideas without Enjolras around, and that makes it seem like he’s being convinced to participate rather than doing it for his own reasons and being one key part of the group.

In the barricade, Enjolras acts as if he doesn’t know what he’s doing half the time, and the other half he doesn’t give a shit about killing soldiers, smiling and laughing while shooting people.

It isn’t just that the scene with Le Cabuc doesn’t exist, Enjolras doesn’t seem to have empathy, which is all given to Grantaire instead.

By taking away Enjolras’s vulnerability, his complexity, they make him seem more shallow overall, and in tow, make his cause lose importance.

And without a clear political standpoint, because his expositions about the situation are very shout-y and unclear, and his speeches are summarized with some actual quotes but without their meaning and true feeling, he seems to be fighting just because, rather than having strong ideals.

Enjolras in the brick is eloquent enough, humane enough, that you understand what he’s doing and why. This Enjolras is a mess that I couldn’t understand at all.

I don’t think people who have never seen, read or heard of Les Mis before will understand Enjolras as a character through this. He’s just a very angry student with weird facial hair (why?) who rants in a cafe while his friends are playing games and making jokes, who is friends with some workers and is the leader because he shouts the loudest but doesn’t seem to know what he’s doing.

And, worst of all, doesn’t seem to care for human life. Which brings me to the next bit...

3. Grantaire

Man, was I excited with this casting choice.

When I heard Turlough was playing Grantaire, I was delighted. And, at the end of the day, his performance was very good, but for a character who wasn’t quite Grantaire at times.

I mean, he wasn’t as off as Enjolras, but he was also so erratically written.

They decided to make Grantaire hesitant rather than a cynic. He didn’t get to express his cynicism or his attachment to his friends (what friends though? only Bossuet had a name other than Courfeyrac and Enjolras) and his involvement with the fight was shown as insecure rather than questioning of ideals.

He is shown conflicted when he decides to fight with them, he doesn’t have any of his long speeches, the Barrière du Maine scene or anything of the sort. He is just...hesitant about death, I guess. About dying and killing people. That’s his conflict.

This has, to me, two big problems attached to it.

First, it’s a simplification of the entirety of Grantaire’s thoughts. It’s taking the cornucopia of drunken philosophy that Grantaire’s voice in the brick represents and replacing it with a single fear, which while very valid doesn’t reflect Grantaire’s true extensive complexities.

Second, it takes away from Enjolras’s humanity. Enjolras is showcased as an indiscriminate machine of shooting soldiers while Grantaire is conflicted about having to do this and, in tow, makes Enjolras’s rejection of him when he leaves and gets drunk like a jerk move of an insensitive asshole.

There isn’t a clear instance of Enjolras giving Grantaire a chance to do something before the barricade and Grantaire failing at it, with all the dominoes symbolism and all the stuff it implies. There isn’t a complementary set of complexities between each other. Grantaire seems to care about human life more than Enjolras does in this version, at the end of the day, because Enjolras’s speeches, even if carrying canon quotes, are inserted in a context in which he laughs while shooting people, knowingly sends Gavroche into danger and chastises Grantaire for being conflicted about human lives at stake.

So, instead of representing Grantaire’s true complexity as a character, they chose to give him something else that they think makes him more dimensional, when, in reality, takes away from his (and Enjolras’s) worth as a character.

All of this is very weirdly intersected with drunken jokes. Sometimes, the jokes and the behavior pays off and is inserted in good moments, sometimes they just don’t know when to stop and they kind of ruin their death scene with them, which is even worse considering it’s one of the few where they’re actually holding hands.

Overall, I think this was a simplification of Grantaire, in a way, a simplification which falls apart without a solid context to exist in. And it’s a pity, because Turlough was good.

4. Gavroche

The only reason I’d want an immediate new adaptation of Les Mis is so we can cast this same Gavroche in a decent one. He’s one of the best Gavroches I’ve ever seen, hands down.

In this case, the problem isn’t with his interpretation or how he was written, necessarily, and all time frame and socio-political simplifications aside, the problem is in how the context reacts to him.

A lot of Gavroche’s agency is deleted in this version.

For starters, his age is kind of all over the place at the beginning. He’s fine by the time of the barricade, but before it’s kind of a mess. As a result, he lives with his parents for a bit longer than necessary and the few times we see him on his own, being his independent self, are in conflict with how his involvement in the main events come to happen.

It feels as if he’s been used in the barricade. When he’s off to find bullets, only Marius tries to get him back to safety, while the rest cheer him and laugh.

His character is well performed and we get to see his personality and his situation when he’s allowed to act on his own, but within the context he’s inserted in, he seems more like a prop than a character.

This makes it so that when he dies, you’re upset more so than sad. It doesn’t feel like a tragic circumstance born out of a lot of layers of social strife which culminate in a dead end for a kid who deserved a better life. It feels like every adult around him, every person he encounters, either neglects him, mistreats him or sends him into danger. It feels, much like with Fantine, like an easily avoidable situation.

And things get worse with this guy:

Like I said in my summary, this David Harbour-ish soldier is the one who is shown to mercilessly kill both Gavroche and execute Enjolras and Grantaire.

This is another layer in the modus operandi of an adaptation who uses social oppression and political strife as shock value rather than commentary and discourse.

By personalizing “evil” in one stern, mean, unreasonable, power-hungry soldier, they’re villanizing (and trivializing) the social context as a whole. It isn’t about how Gavroche got to that point, how we as a society failed so hard that he has to die in that way. It’s just one bad guy.

But then, they try to be fake deep about it, by doing that last scene with his brothers or by placing him alongside Mabeuf and Éponine but not explaining what that means, why those juxtapositions are socially relevant and important to the plot (maybe they don’t know why).

Overall, this was such a waste of a great Gavroche that I just feel really bad. Reece deserved so much better.

5. The barricade

Needless to say, this barricade was more of a mess than you would have expected.

The lack of proper introduction to the political landscape, the clumsy exposition, the out of context shout-y speeches and the erratic behavior of its characters, paired together with the fact that it ends about 1/4 into the last episode, giving more time to personal drama than any of what happens in it, makes it one confusing mess.

It’s also in the barricade where it’s super clear how visually similar this series is to the 2012 movie. A lot of visual choices are extremely similar, even when they didn’t need to be (Fantine’s and Cosette’s hair choices? the shots in the hulks? the scaled down yet very similar camera angles and movements during the entire fight? the color schemes of some particular scenes?), and it’s pretty heightened in this barricade.

Which I wouldn’t care about hadn’t they talked crap about the movie during their entire PR campaign.

Like I said, there were so many issues within the people involved in the barricade. With the women, with the characters, with the soldiers. There was also a very strangely set line between workers and students that they were very clumsy about setting yet didn’t get to do much aside from having the leader of the working class men leave when Enjolras prompted it.

By the way, Enjolras was a lot less convinced about the whole ordeal in this version, which made his characterization even more confusing.

The barricade had a lot of messed up ingredients and not enough time to even simmer. At least the musical, which doesn’t have a lot of time dedicated to the students either, has Drink With Me, which doesn’t only serve as a way to characterize different students and their beliefs and personalities (“Is your life just one more lie?”) but also brings some melancholic change of pace, a pause between the action.

The highlight of this barricade, though, is Marius going apeshit with the torch.

But, all in all, there’s no much we can expect from a barricade born of confused ideas and even more confusing characterizations. This barricade feels less like a climax and more like a thing they had to do because it was in the book.

And don’t even make me talk about how they butchered my favorite speech. I’d rather not have it there at all, tbh.

Conclusion: A writer’s ego

We arrive to the end of this long and boring trip through my thoughts. If you’re reached this point, thank you for your time.

All in all, I feel like a lot of the issues of this adaptation stem from the fact that Davies thinks he’s better than everyone else and other men around him agree so much that they let him do as he pleases, without questioning anything.

I can’t really understand how you’re going through the script of this and see some of these choices (like the dress shop scene, the carriage scene and let’s not even mention the peeing in the park scene) and you go, and I’m quoting Shankland here:

“Andrew’s scripts made these characters feel modern. That was nothing to do with having them speak in a very modern way or changing their behaviour, he just found the humanity and earthiness of it,” Shankland says, recalling a scene in which Fantine and her companions urinate in a Paris park. “I thought, ‘Oh god, they’re going to pee in Les Misérables, that’s exciting.’” Source

That just sums it all up, doesn’t it?

After I watched this, I let some time pass. I watched all 3 fanmade adaptations that are currently out at this moment (back to back), revisited some of the ones I had seen before, read fics, read people’s articles and rants, looked into other adaptations on stage, from the classic ones to the more interpretative versions, and other current tv adaptations being done in other countries.

All of those things are vastly different. Some are more similar to each other, some are widely different, but they’re all different points of view on the same canon.

This is a canon that has some of the wildest possible interpretations coexisting. You can have a play centered on one specific character told through the songs of a specific album, a tv drama in modern times with a lawyer Valjean, a coffee shop au starring Les Amis, a parody comedy set in 1832, all happening at the same exact time.

And that’s great. That’s fascinating. That means this book is still alive because we need it still today.

Some days you’re in the mood for a heavily political adaptation which gives you goosebumps for setting canon in a context that is closer to your everyday reality, other days you just want all the Amis to live and have movie marathons cuddled together. It’s all valid.

But what all of those adaptations have in common is that they aren’t trying to be more than they are. They aren’t acting brand new, they aren’t pretending they’re re-inventing the wheel or that they are smarter than Victor Hugo himself because what Hugo didn’t know he needed in the “psychology of the book” was a soulmate au or a documentary series.

This adaptation, through what they said and how it was written, acted as if it was going to be the ultimate Les Mis adaptation to end them all. It presented itself as smarter than us all, as holding the keys to the meaning of Victor Hugo’s thoughts, as being able to fix his “mistakes”, fix other adaptation’s “mistakes” and deliver the best interpretation of canon possible.

And it managed to be a sexist, socially insensitive, problematic, un-political, homophobic mess.

Which, is a problem in itself, but even more so when the canon you’re adapting should be, first and foremost, against all that. It isn’t about how many brick quotes you use, it’s about channeling the soul of the story.

#les mis#les miserables#les mis bbc#les mis bbc a summary#jean valjean#cosette#fantine#eponine#marius pontmercy#enjolras#grantaire#gavroche#death cw#long post when expanded#luly rambles#bbc les mis

50 notes

·

View notes