#even though this technically isn't due until the beginning of class tomorrow

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

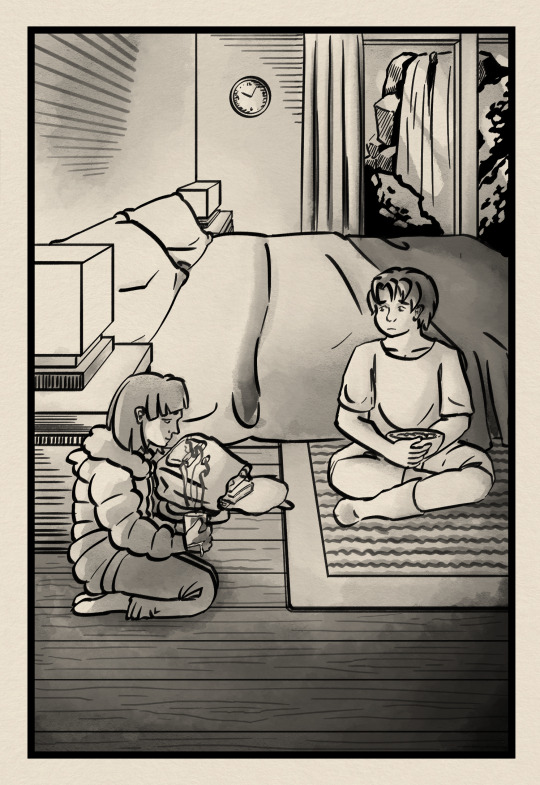

I think i doubt my ability to work faster under stress too much

#classwork#banana yoshimoto#kitchen#so much for lurking#sorry i just like how these turned out haha; this was one of the things that was bothering me so it feels nice to have it done#i don't like the second one as much as the first one but it *is* empty on purpose... metaphors and stuff#this is for my capstone; it's our only art assignment we'll have for the whole semester (intimidating)#we had two options for what to do depending on what kind of focus we've placed on our work#people who were focusing on content for studio work had to make something that represented themself as an artist#people like me who focus more on technique and meeting task requirements had to depict something based on... any... literature#so i took a middle ground and did two page inserts for a book that's important to me#i actually wanted to do only one really detailed insert but my prof wanted two so i had to divide my time#and also read the whole book again which left less time for the actual drawing#crying bc the dropbox for this closed five minutes before I got this done#even though this technically isn't due until the beginning of class tomorrow#it'll be fine since i'm bringing the files to class via USB anyway but it'd be nice to have it submitted so it could leave my conscious lol#uh i also have to type up something for this so i shall do that now#night night

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Observer - May 17 1964

THE BEATLE BACKER

BRIAN EPSTEIN talks to KENNETH HARRIS

HARRIS: How much have you made out of the Beatles, Mr Epstein?

EPSTEIN: Well, I honestly couldn't tell you at the moment.

I wouldn't mind telling you a bit - after all, I have to tell my accountants and the income tax collector. But at the moment I couldn't. You see, I managed them at quite a loss in the first year.

I remember putting them on four successive Mondays at Widnes, and the most I grossed was £18. And it was a long time before I was making enough to pay them what they ought to have and show a profit myself. Its only in the last accounting period, not the current one, that I show a real profit.

If you want an idea of the scale of the thing, at the moment the Beatles can on occasion make as much as £8000 a week. Of course, they can't work every week - not because I couldn't get contracts for them, but because I mustn't overwork them. My percentage at the moment is 25.

HARRIS: Do you think that might be a bit excessive?

EPSTEIN: No, I don't think it is. If you see it as it really is. When I contract people, I do it on the basis of guaranteeing them a certain return over a certain period. It is the guarantee that attracts them. Having got them on my books I am responsible for giving them that return. I'm backing my judgement of their potentialities, coupled with my capacity - such as it is - of promoting and publicising them.

I may be wrong, after all - they may not catch on, they may flop, in which case I have to pay them the rate just as if they had been a great success, until the period contracted for has expired.

Or, as with the Beatles, they may start off and continue at a loss - while I have to pay them as though they were a success from the start - and then start raking it in much later on.

You see, the stakes are high. There is a great deal of money to be made out of managing artists who become 'Top of the Pops' - not only out of the sale of records, but also out of the radio, television and film shows which go with it. But you have to stake a lot to get it.

I recently signed a contract with a group of artists which means that they do pretty well from the word Go, but I make money only if they if they get to the very top.

At the moment, though you might be showing a considerable profit on one group which has really got going, and made its name, after a period which wasn't anything like so good, you might be bringing on other groups starting from nothing.

I have a large office. I have more than 30 people working in it. Their salaries come out of how much I earn, not out of what the Beatles earn. And I want to introduce a lot of talented young people to the public you haven't heard of yet.

What I've done, and what I'm doing, is to spot people who would record discs that I think from my experience of selling records would sell in a big way. But you need something more than is required to make - or sell - one recording. You need somebody who you can rely on to go on and make several good records.

More than that, you need people who have the personal qualities and colorful character to stand up to - and exploit - the various forms of publicity that are necessary to keep their records before the public.

You have to be a judge of what kind of people teenagers want to hear singing attractive music, and out of those you need to be able to select the ones who are capable of having a kind of continuous folklore built up about them, so that the public wants to go on hearing about them, as well as hearing from them.

HARRIS: How long do you think the Beatles will go on?

EPSTEIN: Indefinitely. They are bound to. There's so much talent there. Each one is a remarkable man. Look at John Lennon, for instance. If he ceased to be a Beatle tomorrow, you'd go on hearing about him. Even if he gave up singing. He's got creative ability as a writer.

You know the Beatles write about 90 per cent of their own material. They can't read music, but they do all their own arrangements. I wouldn't predict that they will go on being as successful as they are now as a group.

But they'll go on. Paul McCartney will go on composing, grow and deepen as a composer. And he may well become a gifted actor. George Harrison is a splendid musician, and he has the talent to develop the business side of it. Ringo is a marvellous actor. Marvellous.

HARRIS: What have the Beatles got that other people haven't?

EPSTEIN: Ah, that's not easy to say. I know what they've got - at least I believe I know what they've got - but I don't know enough about words to be sure I could tell you what it is. Well, to begin with, they've got this astonishing naturalness, this freedom from unnaturalness. In private they are unspoiled, unaffected, sincere - themselves all the time, and to everybody, regardless.

In public this comes over in their performance - freshness, lack of professionalism - well, not that, because they are very professional, really. What I mean is that they don't produce any of the tricks or gimmicks or mannerisms or veneer that you associate with professionalism.

Secondly, they are technically extremely competent. They sing very well, they play very well. Then they have original genius - they have this special sense of rhythm: their lyrics are not only well written - they say what teenagers say and want to hear about.

But over and above all that, they communicate with their public far better than any of their contemporaries. They make a contact that is quicker and deeper than other performers.

The communication they make is very pure. Nothing gets in the way. So many artists have to, or do, act to get their effects, behave like somebody they are not, put on an act. But the Beatles just get up and - are!

All the best art is pure, isn't it? It really comes down to clichés, like honesty and simplicity in art. The Beatles come over direct and strong because they are simple and honest human beings.

HARRIS: How much of their success is due to the fact that they have something that this particular generation of teenagers wants?

EPSTEIN: I'm no theorist, and I can't give you a sociological explanation of anything. Quite frankly, all I really know of teenagers is what they like and don't like - I can't tell you why they like and don't like it. I can tell you, I mean, but its only my own idea.

The performers who go down best with youngsters are people who are young themselves - behave young even if they're not - have the easy-goingness, non-stuffiness, non-pompousness and friendliness that young people have, the opposite qualities from the ones they associate with authority in general and parents in particular.

You see, the Beatles behave themselves very well with their 'elders and betters,' but they don't defer to them. They aren't frightened of them, and they don't behave as if they are.

I think teenagers like the Beatles and their music because it's so gay, and easy, and natural, and moves them so quickly and simply. If teenagers like something, they can afford to buy it these days.

Another thing about the Beatles is that they don't seem to come from any particular class background. You don't need to have been to any particular school, or have any particular salary, to enjoy the Beatles. Anybody can get on their wavelength.

HARRIS: If you hadn't met the Beatles, what would you be doing now?

EPSTEIN: I don't know. I might have been still in the business, selling records. I wasn't really very happy there. I was a bit bored, really. It was a good thing for me when the Beatles came along.

HARRIS: Why were you bored with the business? You said you liked music, and you enjoyed selling records, and that you were successful at it.....

EPSTEIN: Yes, that's true. But I did it because, well..... I only went into it because there it was, the family business, and I was the elder son - you know how it is.

Furniture shops is our business around Liverpool. I was selling gramophone records - we have a big gramophone department. We might be one of the biggest sellers of gramophone records in the country.

My mother comes from a Sheffield family called Hyman - my grandfather set up a very successful furniture manufacturing business there. My father's family were also in furniture, but they were retailers. Naturally, my parents wanted me to go into the family business - as the elder son. I'm 29.

When I met the Beatles I was in charge of our gramophone records section. That's how I heard of them.

I liked selling records, and I liked talking to the people who bought them, and I found I was getting quite a good idea of what records would sell and what would not. I found that a lot of kids were asking about 'The Beatles.'

It struck me that there was more than local patriotism in it. I thought I'd like to hear these boys. So I went to the place where they were singing. As soon as I heard them I thought they had something. I felt they were great.

And I liked them, liked them very much indeed. I liked them even more off the stage than on.

HARRIS: Had you wanted to have a life outside the family business?

EPSTEIN: That's a long story. When I left school I wanted to be a dress designer. I love things that look well - which I think look well, I mean; you may not - and I love the idea of creating and designing them. I believe in taste. I believe in my own taste, and I wanted to embody it in designs.

I don't know whether I'd have been a success - I think I would. But that's what I wanted to do. My father wouldn't hear of it. Of course, I was only a kid, and I couldn't really explain myself to him.

And he thought he was doing it all for my own good, I am sure. So I was apprenticed to the Times Furnishing Company in Liverpool.

I didn't like it much. I didn't like being at home, being dependent. I didn't like the atmosphere of middle-class commercialism.

Nothing wrong with it, I just didn't like it. But I didn't know quite why I didn't like it. When I was 21 I asked my father if I could go to London to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art for a year. He was very nice about it, and said yes. He'd pay, too.

I didn't enjoy it at all. I didn't fit in - I felt a bit like a fish out of water - I didn't do anything that could be made to look like a success. I felt lonely in London.

So I went back to Liverpool and the furniture business, with my tail between my legs, I suppose. I'd had my chance to break out. Now I had to accept the result and - fit in.

HARRIS: Why did you feel lonely in London?

EPSTEIN: I was shy. I am shy. I like people very much - that's what living is about, as far as I am concerned, being with people, and doing things for people, liking and being liked - but it's one thing to want company and to want the feeling of being wanted and another to get it.

And I didn't feel that I'd made any kind of impact on anybody at R.A.D.A., had any kind of success, so my parents' kindness had been wasted, and my initiative hadn't come off. There was a sense of let-down, frustration, and only oneself to blame.

HARRIS: Were you shy at school? Did you mix at school?

EPSTEIN: No, my school days were rather sad days.

HARRIS: Where did you go to school? Boarding school?

EPSTEIN: Yes.

HARRIS: Where?

EPSTEIN: I went to several.

HARRIS: Why?

EPSTEIN: Because I wasn't very happy, so my parents kept on trying other places. I ended up quite happily, so I can't complain.

HARRIS: Why were you unhappy?

EPSTEIN: Well .... I was interested in a lot of things most of the others weren't interested in. I liked games - but I was very keen on music and art. The last school I went to was a much more modern-minded place than the others.

HARRIS: Were you unhappy because you were a Jew?

EPSTEIN: Yes. There was a certain amount of that.

HARRIS: Anti-Semitism?

EPSTEIN: Well, that makes it sound much more serious than it was. You know how things can be at a school. But it did make me unhappy, and I suppose it had the effect of making me withdraw into myself, and making me want to be good at things that gave me pleasure as opposed to being socially acceptable.

HARRIS: Do you have these tensions and feelings of frustration now?

EPSTEIN: No. The past two years have been wonderful.

HARRIS: So the Beatles solved your problem for you?

EPSTEIN: Yes. It's a funny thing, and I've never thought about it that way before. But it's quite true. Everything about the Beatles was right for me. Their kind of attitude to life, the attitude that comes out in their music and their rhythm and their lyrics, and their humor, and their own personal way of behaving - it was all just what I wanted.

They represented the direct unselfconscious, good-natured, uninhibited human relationships which I hadn't found and had wanted and felt deprived of.

And my own sense of inferiority evaporated with the Beatles because I knew I could help them, and that they wanted me to help them, and trusted me to help them.

Then the success I registered in social and money terms was important. It didn't matter much to me in myself, but it mattered to other people.

My parents were impressed that I had shown good judgement and initiative, so I felt I hadn't let them down. So my tensions and frustrations all went. I've got plenty of problems. But I'm not pulled down by them any more.

HARRIS: Does it irk you when some people say they think you aren't a very good agent?

EPSTEIN: Only if it applies that I think I'm a good agent. I'm an amateur as an agent. I don't pretend to be a good one. I don't think of myself as an agent. I don't want to go on being an agent, anyway.

HARRIS: What do you want to do?

EPSTEIN: I want two things. First, I want to go on being in touch with my artists. I don't want to manipulate money.

I want to be able to influence and help personally the people that work for me - I want to help them realise themselves, give the best they can. I believe I can help them, and I want to be near enough to help them.

At the moment I've got eight groups of artists on my books, and I can keep close to them, go across to the States with them for a few television appearances, see that everything is all right - everything. Some of the big agents have 150 artists on their books. The problem there is keeping in touch.

If you've got the gift, you can delegate, but you can't delegate and keep in personal touch. It's impossible. That's why I shan't devote myself to being an agent. And that's the second answer to your question. I want to direct, present and produce straight plays. That would give me the kind of work and the degree of personal contact with artists which is ideal.

I might not be any good at it, but I want to try it. I may lose a lot of money. But I'm not interested in money. I don't need much to meet my needs. As long as the money is coming in, I just don't care about whether I could be making more, whether anybody is getting more out of me than he should.

I get the best deal I can for my artists, of course. That's a different matter. I've got a responsibility towards them to do that.

But so far as I'm concerned personally, I'm not that interested. Some agents are very hot on contracts. I'm not. I never even saw a film contract till the Beatles made a film and had to sign one.

HARRIS: Do you have any sense of mission about the theatre?

EPSTEIN: No. I want to put on the great dramatists, and I would like to try to discover new ones. But I don't feel that the public ought to have good plays. I think the public wants good plays, so I don't see why they shouldn't have them, and it will give me a great sense of satisfaction to direct, present and produce those plays. But there's no 'ought,' so far as I'm concerned.

HARRIS: You don't have any moral feeling about culture?

EPSTEIN: No. Culture is the entertainment of people with good taste, that is to say, people who enjoy beauty and are honest enough not to pretend they are enjoying themselves when they are not. It needn't be classical music. It can be good clowning. Arthur Askey in my view is a great artist. Very witty, too. When I met him for the first time the other day, he said: 'Ah, how do you do, Mr. Epstein. I used to know the other chiseller.'

HARRIS: You aren't worried at the thought that you and your Beatles might be having a bad effect on teenagers?

EPSTEIN: What bad effect? Some people talk of teenager hysteria about the Beatles. I don't see it.

If they break things up, that's bad. Quite different. But what's wrong in a good scream? Their fathers and their grandfathers roar their heads off at football matches on Saturday afternoons.

I saw a girl sitting in the front row the other night. She had her hands to her head and she was screaming - you know, 'Aieeee' -you say screaming, but they're not shouting 'Help!' or 'Murder!'

In the middle of it, her handbag dropped off her lap. She stopped screaming, bent down, picked it up, had a quick inspection to make sure nothing had fallen out or got broken, put it back safely between her thigh and the edge of the seat so it wouldn't fall again, put her hands to her head, and started up again 'Aieeeee!'

That's not hysteria, that's self expression.

HARRIS: A last question then, Mr. Epstein. You say you haven't a sense of mission, though you have a personal ambition, and you say you aren't interested in making money. Are you going to use your money to do anything which hasn't been done already?

EPSTEIN: Yes, I am. At the moment the public is being given too much in the way of entertainment which is in the bill not because it is the best available or because the public wants it, but for reasons of show-business politics. I want to try to use my capital to put on what I think is the best of its kind.

You see, Mr. Harris, even when you're only 29 life is short, you get older every day, and if you are interested in doing things for and with people there just isn't time to hang about looking important. You want to get things done.

23 notes

·

View notes