#because what is the Vanitas genre about? it's a reminder that life is fleeting

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

One of the most devastating things about Pandora Hearts is that, at its core, it's a story about moving on...but it's also a story that no one can ever (fully) move on from.

#we are all Gil in that second pic :')#also- hello- Oz waving to Vanitas in that art is so fitting with the theme of moving on#because what is the Vanitas genre about? it's a reminder that life is fleeting#pandora hearts#jun mochizuki#mochijun

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

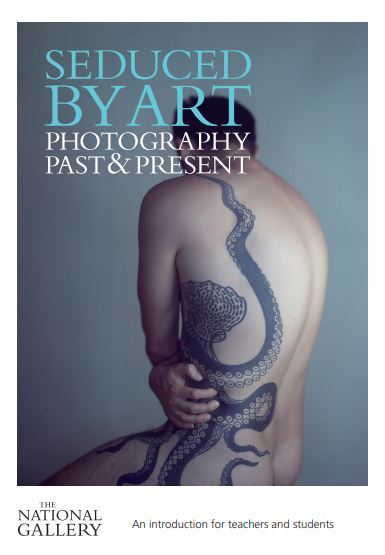

Seduced by Art: Photography Past and Present - Book by Hope Kingsley .

I found this book PDF online that study’s the nature of art involved in photography - Past and Present. 'Seduced by Art' takes a provocative look at how photographers use fine art traditions, including Old Master painting, to explore and justify the possibilities of their art. Right from the beginning, photography dared to claim traditional ‘high art’ subjects as its own. Far from being a general survey, the exhibition draws attention to one particular and rich strand of photography’s history, in major early works by the greatest British and French practitioners alongside photographs by an international array of contemporary artists. It delves into the beauty involved around time and how the change of appearance that be what we have made of it. I have picked out the key points I took from reading this and referencing them to what I have learned from the art shown -

Pioneering Photographers -

Louis Daguerre

Daguerre’s invention did not spring to life fully grown, although in 1839 it may have seemed that way. In fact, Daguerre had been searching since the mid-1820s for a means to capture the fleeting images he saw in his camera obscura, a draftsman’s aid consisting of a wood box with a lens at one end that threw an image onto a frosted sheet of glass at the other. In 1829, he had formed a partnership with Nicéphore Niépce, who had been working on the same problem—how to make a permanent image using light and chemistry—and who had achieved primitive but real results as early as 1826. - With this section pointing out that Louis Daguerre introduced the first photographic purpose and stating that each dagueriotype was unique.

William Henry Fox Talbot

Some five years before Daguerre went public, the British inventor Fox Talbot was making good progress with his version of photography at Laycock Abby, Which I had the pleasure of visiting on last years trip that allowed me to broaden my concept of overall photographic boundaries. Talbot’s use of negative and positive become the basis for almost all 19th to 20th century photographs. Where as the daguerreotype died out 30 only years after it’s beginning. This section is a clear reminder of the learning of beginning and how both photographers pasted down their knowledge.

Expression & Memory: Portrait Photographs -

For centuries a painted or sculpted portrait was the only way to record a face, be it a king, a hero, a socialite or celebrity. The invention of photography in 1839 changed all this, giving many aspiring photographers the opportunity to earn a good living recording the middle class in formal studio portraits. The poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, in common with many others, was entranced by the new photographic portraits. She preferred them to a fine art portrait ‘not in respect (or disrespect) of Art, but for Love’s sake’ she wrote, describing her feeling that the photograph was a closer description of the features of a loved one. The first time she saw a daguerreotype she described it as ‘like engravings – only exquisite and delicate beyond the work of a graver’. It is strange to reflect that prior to photography by far the majority would never have possessed an image of a loved one. A painted portrait was of course a hugely time consuming, and consequently expensive process – inevitably a privilege for the rich. The affordability of the daguerreotype made portraits available to a much wider group. The art critic P. G. Hamerton wrote in 1860: ‘A poor soldier’s wife can now get a more authentic miniature of her husband for one shilling, than a rich lady could have procured a century ago for a hundred pounds’.

This part explained the importance that can come from remembering old expression art and incorporating it into my own photography.

For example (Below):

Martin Parr - A sign of the times:

In relation to Mr and Mrs Andrews By Thomas Gainsborough:

STUDIES OF TIME AND BEAUTY: STILL LIFE PHOTOGRAPHY.

Although ostensibly still life is a collection of inanimate objects assembled to demonstrate an artist’s skill, throughout the history of art the still life has often been rich with meaning, containing symbols of war, religion, sex and death. Contemporary photographers continue to explore and reinvigorate the genre. Dutch 17th-century art is arguably the richest for still life. Artists such as Balthasar van der Ast specialised in the genre, concentrating their astonishing skills on the depiction of flowers and insects. Such works can provide a seductive illusion, celebrating the beauty and opulence of the natural world and appealing to all our senses: sight, touch, taste, smell and hearing. But flowers wilt and insects die. Likewise our lives are transient and ephemeral. These phases of life are a part of the vanitas tradition, where beauty is but a passing thing and death is always closing in. Vanitas means emptiness in Latin and expresses the transitory and meaningless nature of material existence.

Sam Taylor wood - Still Life

Supper at Emmaus (Caravaggio, Milan)

WILD POETRY

In 1868, the French critic Ernest Chesneau called landscape painting ‘a place of asylum, apart from the devouring activity, the continuous fever of the city’. In today’s fast- paced world, a contemporary photographer of landscape might agree. In Western art, landscape played an increasingly important role from the 16th century onwards. But it was not until after the industrial revolution, that the natural world became more revered and celebrated; the painting of landscape came to be seen as an important genre in its own right. Landscapes could be seen as a way of contemplating the beauty of the natural world, reflecting the spiritual in man’s nature. The rise in the importance of landscape painting coincided with the invention of the camera; from the outset photographers were wrestling with many of the same issues as the painters. Both paintings and photographs of landscape in the 19th century reflected a desire to escape the rigours of modern life and the increasingly industrial world.

Gustave Le Gray (1820–1884) The Great Wave, Sète

Although Gray captures transitory effects, his process was anything but instantaneous. The comparatively slow shutter speeds available to him at the time made it impossible to create this scene in one shot. Instead, he innovatively combined three: he added the clouds from a different negative and the immediate foreground from another.

Peder Balke (1804–1887) The Tempest, about 1862

In this small painting, no larger than an envelope, Peder Balke captures the eye of a storm in his native Norway. He communicates nature at its most violent; two boats are in danger of being overwhelmed by the giant waves which have been painted at speed and with incredible freedom. The limited palette of white, grey and black tones is both arresting and reminiscent of a photographic plate.

TO CONCLUDE ON MY RESEARCH:

Through depictions of the then and now of some of the most historic and interesting paintings/photographs I have found that all art created in originated from an original in some form - whether it be on purpose or not we find our images relating to art in composition or lighting that link them together. The reason I read into this is because I wanted to get an understanding copying through the ages - which is essentially what I will be doing for my first shoot with comparing past to present in an editing process - this was indeed amplified when researching about Louis Daguerre and the process that lead him to create a following in his name. Another I found particularly interesting was the Martin Parr - Sign of the times image being similar to the Mr and Mrs Andrews By Thomas Gainsborough, it just shows me how much I can take away from this and think about the kind of narratives that can be performed through staging or through everyday. The Sam Taylor wood animation was extremely interesting as the photo acts as the reminder of whats to come. To conclude, I found this PDF exhilarating to look into and is a great help when understanding my main focus and possible methods as it resides with the times.

PDF LINK:

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/media/31355/notes_seduced-by-art.pdf

0 notes

Text

About My Project

In this post, I will explain my audiovisual project in the following order;

1. My project and aims

2. Broader context of my research

3. Details of compositional process and methodology

1. My project and aims

In the age of media dominating and interacting with people’s daily lives, it is hard to experience music independently – it is almost always understood in relation to other media, like album covers, music videos, fashion, artists’ image or even fan art. The visual accompaniment helps giving narratives, adding extra meaning and a possible interpretation of the music. It confronts people “with audiovisual situations that are familiar to us from life”, and in that way it is unavoidable for them to respond both physiologically and emotionally.[1] Holly Rogers argues that music videos give recorded music the energy and physicality of live performance.[2] It seems the visual aspects are almost something that makes music – or even its audience – feel more alive. The focus on audiovisual culture seems to be about making something into more real experience. For example, people like to be amazed by power of life through ultra high definition nature/animal documentaries, or in the cinema, surround systems and 3D, or even 4D, are becoming commonplace. Or even “something larger than life”, on that matter, the use of virtual reality technologies which can be seen in Bjork’s music videos like “Notget”, gives the audience a possibility to experience a kind of sublimity, and provides an escape from reality.

Music is considered something to give life to a piece of media as well; Peter Larsen argues that images of the silent film were thought to be “a ghost-like replica of the world we live in”, and it was the music that lit up “the pale silent images on the screen so that they will stay with us.”[3] This nature of music applies to music videos too; Carol Vernallis argues that it is music that fills in the two-dimentional images that lack elements such as weight, density, and scale.[4]

If these media is full of life, how, then, can the audiovisual work express quite the opposite concept?

“枯れる(kareru)” is a Japanese word that is used when something is dying or withering such as flowers, and plants that are drying out, or earth that is short of water (涸れる), when a voice is getting hoarse (嗄れる), or when talent is ruined (枯れる). My fascination with the phenomenon of kareru is for a rather autoethnographic reason. The motive behind my fascination is mainly for two reasons;

Firstly, I am afraid of time passing by. I feel like my power, advantage, and freedom are going to be taken away and my youth is fading more and more each day. I fear that sense of loss. It’s almost like being afraid of death.

Secondly, I have anxiety over the impermanence of being. Since I have started to live alone and abroad, separated from my family and friends, this fear has only got more intense. Especially in 2016, that feeling was strong because of mass shooting, terrorism and that many musicians and icons I looked up to passed away, I am in terror and awe at the vulnerability and mortality of human beings. I have been avoiding confronting it, but those experiences make me want to think about it through creative work.

For those reasons, the concept of “枯れる (kareru)” is resonant with my mentality. This word has so much meaning yet it is difficult to translate in another language. My question is how the relation of music and images can express “kareru”, and my goal is to do it without needing to directly explain in English words, and examine how this quiet decay has been expressed in both Western and Eastern society.

[1] John Richardson, et al., eds. The Oxford handbook of new audiovisual aesthetics. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 6

[2] Holly Rogers, Visualising music: audio-visual relationships in Avant-Garde film and video art. (Saarbrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2010), 42

[3] Peter Larsen, Film music. Trans., by John Irons. (London: Reaktion, 2007),188

[4] Carol Vernallis, Experiencing music video: aesthetics and cultural context. (New York: Columbia University Press 2004), 105

2. Broader context of my research

The first step in the process would be to investigate the relationship between music and images. Carol Vernallis describes that a music video is like “a laboratory where relations among music, image, and text could be tested.”[1] She suggests that it would be useful to think “music video’s mise-en-scene as separate tracks on a recording engineer’s mixing board”[2]; a music video has flexibility that “any element or combination of elements can be brought forward or become submerged in the mix.”[3]

Walter Ong argues that

“Sight isolates, sound incorporates. Whereas sight situates the observer outside what he views, at a distance, sounds pours into the hearer. Vision dissects… When I hear, however, … I am at the center of my auditory world, which envelopes me, establishing me at a kind of core of sensation and existence…”[4]

According to him, how human beings perceive through eyes and ears is fundamentally different; the visual ideal is typically clarity, whereas the auditory ideal is unifying harmony. Vernallis makes an interesting argument for the difference between the act of seeing and hearing. She claims that people perceive images as something like grammatical nouns; something that can be owned and earned. [5] Images have strong specificity of objects; they “can be described with great linguistic accuracy.”[6] In contrast to images, sound is like a verb or adjectival form because it is often a process or an action of an object. It would be more ambiguous to define sounds with linguistic term, and whether sound is something can be owned is still controversial. Sound is a process; it begins and ends. Objects are generally static and its existence is more non-transforming than sound. Kareru is exactly a process of the object “that begins and ends.” Kareru is a verb in Japanese and in order to express the process, it might be appropriate for it to be represented in audiovisual media, like a noun (sight) and a verb (sound) complete a sentence.

Vernallis argues that music videos does not provide complete narratives but rather give units of stories fragmentarily or episodically for several reason. It is difficult to present fleshed out stories like in a film partly because music videos usually have many roles to achieve such as “showcasing the star, reflecting the lyrics, and underscoring the music.”[7] Also music videos often lack enough details about place, time, and characters to let audience fully understand the narrative.[8]

The need for the structure of a music video to follow the song form also makes it difficult for the creators of the music video to provide narratives like a film does. David Fincher, a film director who also shoots music videos says that he quickly abandoned the approach that aims to tell a straight stories but rather on that create several segments instead. [9] Holly Rogers argues that a music video can be considered as inversion of the relationship between film and film music, since music comes first in music video when creating a music video whereas film music is often scored during the post-production.[10] In other words, “the image interprets the music” in a music video, whereas in film music the images have denotative function and the music connotes image’s context.[11] Since kareru is a usually slow, almost timeless but immortal process, in this project a sense of time and movement of the work should be the music.

[1]Vernallis, Experiencing music video, introduction

[2]Ibid., x

[3]Ibid.

[4]Walter J Ong, Orality and literacy: the technologizing of the word. (London: Routledge, 2002), 32

[5]Vernallis, Experiencing music video, 176

[6]Ibid.

[7]Ibid., 4

[8]Ibid.,15

[9]Ibid.,

[10]Rogers, Visualising music, 41

[11] Vernallis, Experiencing music video, 195

3. Details of compositional process and methodology

There is quite a few elements in music video such as characters, settings, spaces, textures, and colours. In this article, I am going to focus objects. Objects in music video can possess meaning that other elements like characters, lyrics, music cannot without interfering with the flow of the audiovisual work. The object can carry “a set of culturally determined meanings, values, and uses.”[1] Holly Rogers argues that images not only embody music with physicality but also enables music to construct an alternative world.[2] Music videos rarely present unedited live performance but have its own world and because of that it can be complicated to understand the relations between the sound, image, and lyrics. In such a situation, it is crucial to understand the metaphor of objects as semiotic index. In the sixteenth and seventeenth century in Flanders and the Netherland, a genre of still-life painting, ‘vanitas’ emerged. It is derived from the Latin word, vanus, meaning empty and vain. It symbolizes worthlessness of earthly pursuits and the inevitable passing of time, and is also considered as a reminder of self-introspection; “how priviledged you may be in this life, humility was the key to your entry into the next”.[3] Painters combined emblematic organic motifs that signify mortality and decay, such as skulls, flowers, animal carcasses or fruits with everyday or precious objects like hourglasses, candles and musical instruments.[4] This kind of spiritual contemplation is also prevalent in other art forms such as Cadaver tomb/Transi, and crafts like watch cases. The most famous one would be Mary Queen of Scot’s skull watch which has four Latin memento mori inscription: “vita fugitur (life is fleeting)”, “caduca despice (look down upon a fallen thing)”, “aesterna respice (look upon eternity)”, and “incerta hora (the hour [of death] is uncertain)”.[5] Interestingly enough, seventeenth century Japan has the similar state of mind towards the world, “浮世 (Ukiyo)”. Literal translation would be “floating world”, and it is said to be the homophone of “憂き世”, meaning sorrowful world. The Buddhist philosophy was largely entrenched all over the country, and this culture of the Floating World foregrounded inevitable vicissitudes of the world and the transient nature of our existences. Due to its “cognitive condition of being apart from ‘fixed’ world of daily life and duty”[6], the urban life style of Edo period was considered to be a kind of epicureanism that people should enjoy life even if it is vain to do so. An American band, Nine Inch Nails used vanitas aesthetics in rather graphic and explicit context in the style of super 8mm film.

vimeo

The objects like shells, skulls, maroon drapes, insects, animal heads can be seen in the video, and the lead vocalist, Trent Reznor is presented as a skull in the setting of still-life painting. This proves that objects in music video are utilized to make viewers understand references or metaphors without interfering with the music, lyrics, and the sequence of images. Although the video shows a striking contrast between life and death like vanitas paintings do, vanitas element seems to be exploited mainly as the agony of living; Life represented by crucifixion of the monkey and agonizing insects is quite disturbing. The main focus of the video is not ephemerality of time or transience of earthly pleasures, and certainly not the process of slow quiet decay, kareru. The audiovisual works which focus on this subject are not quite prevalent.

youtube

This is an alarming TV commercial about global warming, not music video, but it does express this process audiovisually. It shows green leaves in the shape of a human and a dog, in sunny weather with peaceful music, but soon followed by them dying rapidly whilst the pitch of music goes down. The music and the images are moving in synchronization to tell the story efficiently, with little words in such a short duration. If one attempted to explain what this adverts tries to tell, it would have been lengthy and not quite as effective – this efficiency and expressiveness is my aim. The process of decay or withering is not a common theme for music, but death is. Music has been used for resting the souls of deceased people in the form of Requiem. Death is also often a significant element for many operas; Henry Purcell’s Dido’s lament is a beautiful example of it. I chose to use sound recorded by field recording as a methodology of the composition since noise is fundamental within life. John Cage said that “Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise”.[7] That means as long as we live, we cannot escape from noise. Jacques Attali, too, insists that “life is full of noise and […] death alone is silent: work of noise, noise of man, noise of beast”.[8] Thus so far I recorded sounds which evoke sense of life and death, such as heartbeat sounds by contact microphone, breathing sound of a sleeping person, and a singing bowl, because in Japan it is used at Buddhist funerals and one was placed on my grandfather’s altar. My goal is to create an aural collection of everyday sounds and noise like vanitas paintings did visually with everyday objects. Music is volatile; it symbolizes life and death at the same time. It is used to give other media life but is also essentially ephemeral, as it has its end without exception in most of cases. But what about the process in between that is quiet decay? To express that is my aim.

[1] Vernallis, Experiencing music video, 99

[2] Rogers, Visualising music, 42

[3] Joe La Placa, et al., Vanitas: the transience of earthly pleasures. (London: AVA All Visual Arts, 2011), 7

[4] Ibid., 10

[5] British Museum Collection Online watch-case, Accessed 7 Feb, 2017

[6] Timon Screech, Sex and the floating world: erotic images in Japan, 1700-1820. (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1999), 10

[7] John Cage, John Cage: an anthology. ed. Richard Kostelanetz. (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1991), 54

[8] Jacques Attali, Noise: the political economy of music. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 3

0 notes