#antiquitez de rome

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

FLAVIUS JOSEPH

HISTOIRE DES JUIFS

Ecrite par Flavius Joseph, sous le titre de Antiquitez iudaiques.

Traduit par Arnauld d’ANDILLY

COMPLET EN 5 VOLUMES

A Paris, Chez Pierre le Petit, 1674. in-12 de [28]-500-[10 + 509-[18] + 398-[86] + [30]-LXVI-[8] + 368-[16] + 550-[38] pages

Flavius Josèphe, auteur Juif qui vécut en Palestine au 1er siècle, un certain nombre d’ouvrages historiques, apologétiques et autobiographiques constituant ensemble, un élément important de la littérature juive hellénistique. La version araméenne originale de sa première oeuvre, connue sous le nom de Bellum Judaicum ou La Guerre des Juifs, n’est pas parvenue jusqu’à nous; cependant, la version grecque en a été conservée par l’Eglise, tout comme les autres ouvrages que Josèphe écrivit en grec pendant son exil à Rome après la destruction de Jérusalem, et ce, particulièrement en raison de l’importance générale de ces textes pour connaître l’histoire de la Palestine aux débuts de l’ère chrétienne, et du curieux Testimonium Flavianum que l’on trouve dans les Antiquités judaïques sur le fondateur du christianisme.

Reliure d'époque plein veau à nerfs, dos orné de caissons à fleurons dorés, pièce de titre, tranches rouges

0 notes

Photo

- Isobel Robinson

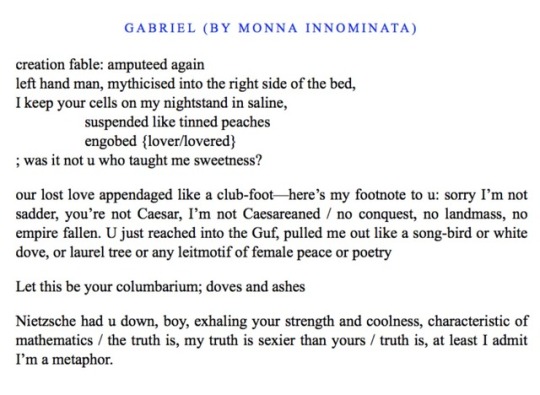

This is more a written piece rather than spoken word! I wrote it after a break up and it was super therapeutic !!! I also submitted it as an assignment for a class I was taking at the time about Renaissance poetry and literary imitation... Here is the short commentary attached:

Reflection on Imitation

To begin, I intend to make some opening remarks about my approach to writing my ‘sonnet’, followed by a line-by-line commentary which should serve to elucidate individual linguistic, rhetorical and grammatical decisions. The primary emotional context of the poem’s genesis was the breakdown of my relationship with my now ex-boyfriend, thus the tone of my ‘pseudo-sonnet’ and the poetic voice I have chosen to invoke are petty, ironic and somewhat histrionic in places, but not without a degree of sincerity.

At the time of writing, I had been reading on Petrarch and Petrarchism interspersed with Nietzsche, which was required reading for another module I am taking. I subsequently decided to ironise, through a poetic dialogue, both humanist and anti-humanist tenets. During my reading, the humanist reification of classical rhetoric (such as Ciceronianism) as the pinnacle of literary writing frustrated my postmodern, fourth wave feminist, Marxist1 and millennial sympathies. Fascinated with critical debate on literary aesthetics, I considered the various sources of inspiration which inform my own poetic style. There is something, I find, in the poetics of obsession. From Petrarch’s 366 unanswered poems in the Rime Sparse (taking the millennial notion of ‘double texting’ to the next level), to Carol Ann Duffy’s narrative love-poem(s) in ‘Rapture’, I observed that there is something about the dialectic between the object of desire and the formulation of the self which is literarily irresistible. I have taken inspiration from these texts and paired this with the ironisation of the humanist dilemma2 and postmodern solipsist and totalising propensities. The formulation of a specifically female, millennial, postpostmodern écriture that is at once confessional, candid and interrogative was another stylistic consideration.

The title of the poem focalises the poetic narrative through the medium and discourse of

1 See ‘Aesthetics and Politics’ for Marxian discourse on autonomous art and notion of genius. 2 Simultaneous anxiety of influence and unflinching reification of genius.

obsession. I took the Biblical figure of the archangel Gabriel as a poetic substitution for my beloved and the initial image of Gabriel as the deliverer of the news of the Virgin Mary’s ‘fullness’ to serve as a metaphor for the sense of completion I associated with my ex-boyfriend; using the character as an extended metaphor for the fallacy of fulfilment of the self by (an)other. My decision to add the parentheses ‘By Monna Innominata’ was inspired by my reading of Christina Rossetti’s sonnet series, which both imitates and surpasses the work of seminal male sonneteers—primarily Petrarch and Dante (Moore 485). It plays on the notion of the female as object of desire and asserts a specifically female voice.

In my writing, I tend to play with indentation, enjambment, punctuation and stanzas fairly unconventionally. The opening stanza of the poem features two indented lines, which I have suspended in the middle of the page to reflect their meaning. The phrase ‘creation fable’ is a reference to the beginning of Nietzsche’s ‘On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense’, where he uses a demonstrative literary rhetoric to establish his theory of ‘truth’ as a human act of associative metaphorisation. This is an important theme throughout the sonnet, as I explore the notion of subjectivity and validity of experience of the self in unrequited love. The opening line is also in iambic pentameter, but I subsequently break the metre in the vein of Carol Ann Duffy, and the way she takes then breaks traditional sonnet forms to emphasise the unconventionality of her love poems. With the phrase ‘amputeed again’ I begin the motif of the disembodiment of the beloved. This is in part direct reference to Petrarch’s ‘scattering of Laura's physical features as a kind of defence tactic, one that works against the "threat of [his own] imminent dismemberment" implicit in his reworking of the Actaeon-Diana myth towards the end of canzone 23’ (Vickers in Leubner: 1081), and also Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘Absence’ (Duffy: 10) which examines the relationship between desire and objectification of the beloved. The line ‘left hand man’ is reference to Jewish portrayals of Gabriel as standing at the left hand of God (Alder 1906: 540–543). It also creates an oppositional structure with ‘right’ in the following line, in typical Petrarchan parallelism. Subsequently, the phrase ‘mythicised into the right side of the bed’, invokes a sense of the contemporary poet as capable of mythologising.

The last few lines of this stanza further the fragmentation of the beloved, whilst involving a a sense of the preservation of loss and the continuation of desire following the untenability of a relationship. The semantic field of food is employed to portray the object of desire as consumable and materialised through the creative act—this is something also explored with the reference to ‘engobe’; the idea of forming the beloved (in retaliation to thinking that my ex-boyfriend completed me). I use curly brackets in this phrase to reference my beloved’s mathematical and musical background; in music, braces can connect lines that are played simultaneously, whilst mathematical sets are used to group together distinct objects which are also considered as a whole. Therefore, my use of punctuation here communicates the simultaneity of the relationship being at once over and enduring through my own experience of the aftermath, as well as the notion of separation of the self and the beloved in a couple. This is echoed with the floating semicolon in the next line. The final line of the first stanza uses a slant rhyme with ‘peaches’ to mirror the alternate end rhyme structure of the Shakespearean sonnet (but also in the sestet of Petrarchan sonnets). It is a direct, retrospective and ironic reference to lines 13 and 14 of Rossetti’s ‘Sonnet 1’, playing on the idea of the mediation of experience of the self through the validation of the beloved. I wanted to incorporate here the sense of a female subjectivity, which Rossetti enacts using ‘rhetoric and figuration like those of Petrarch, including the rhetoric of self-analysis that fragments his speaker, but emphasising aural over visual sensuousness and thus avoiding visual imagery and metonymic praise, techniques that objectify the female or feminised beloved’ (Moore: 487).

The second stanza of my poem features a volta face. The tone of the stanza becomes more polemical and petty, which is mirrored by the playful euphony and prosody of its sound and the quickening of the pace administered through sibilance, alliteration and litany. The caesura following the phrase ‘like a club-foot’ is a metapoetic element following Nietzsche, which literally appendages the phrase from the rest of the verse. The rest of the stanza works through wordplay and reference to Ancient Rome. Whilst writing these lines I considered Petrarch’s RVF 85 and the line

‘love with what power today you vanquish me’ (Durling: 188); the idea of love as violent or imperial. I also imitated to some extent RVF 128 and the artistic implications of politicising (in my case asserting female agency and strength) alongside eroticism and desire (Durling: 256). Petrarch here attempts to recompose the fragments of his beloved motherland, but I have chosen to leave my object of affection dismembered and scattered over the page. For clarification, the phrase ‘reached in the Guf’ is another reference to Jewish scripture about Gabriel. My ex-boyfriend has Jewish heritage, and I liked the image of Gabriel picking souls out of a chamber to bring them into existence. This is again playing on the notion that I felt validated and legitimised by the relationship, but the flippant tone ironises this retrospectively.

I chose to stand the line ‘let this be your columbarium’ alone to act as a link between the images invoked in the second and fourth stanza. It refers to Nietzsche’s essay and his criticism of scientific and mathematic rigidity (Nietzsche: 112). The line also serves to juxtapose the image of the death of a relationship as an extinguished flame (in the spirit of Petrarch’s leitmotif of fire and ice) with a typical image of peace associated with weddings (the dove). Obviously this is also a nod to Ancient Rome, whence came the columbarium3.

The final stanza continues my use of colloquialised text-speak (inspired by Carol Ann Duffy’s use of text references to modernise and parody her relationships) in direct address to the subject. The address is at once interrogative and a direct allusion to lines from Nietzsche’s ‘On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense’ in which he asserts the sublimity of the ‘perceptual metaphor’ over empiricism (Nietzsche: 112). The closing lines of the poem use the anaphora of the dental plosive ‘truth’ to cacophonically reassert the tongue-in-cheek forcefulness of the poetic voice’s tone. I chose to finish the sonnet with a rhyming couplet to deviate from the typical Petrarchan sonnet, and evoke my national vernacular tradition in that many forms of English sonnets culminate in a rhyming couplet.

Bibliography

Adler, Cyrus, and Isidore Singer, The Jewish Encyclopaedia (New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1906), pp. 540–543.

Duffy, Carol Ann, “Rapture”, (London: PICADOR, 2017), p. 10

Leubner, Jason, "Temporal Distance, Antiquity, And The Beloved In Petrarch's Rime Sparse And Du Bellay's Les Antiquitez De Rome", MLN, 122 (2007), 1079-1104 <https://doi.org/10.1353/mln.2008.0028>

Moore, Mary. “Laura's Laurels: Christina Rossetti's ‘Monna Innominata’ 1 and 8 and Petrarch's ‘Rime Sparse’ 85 and 1.” Victorian Poetry, vol. 49, no. 4, 2011, pp. 485–508. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/ 23079669.

Nietzsche, Friedrich, "On Truth And Lies In A Nonmoral Sense", in From Modernism To Postmodernism (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), pp. 109-116

Petrarca, Francesco, and Robert M Durling, Petrarch's Lyric Poems (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), pp. 188, 256

Rossetti, Christina Georgina, and Simon Humphries, Poems And Prose (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 227

3 Etymologically derives from Latin ‘columba’, referred to compartmentalised dovecote.

0 notes