#and you end it by showing your female cast face oppression and suffering. and then they don't win.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

like it really is enough to make someone feel crazy. you have a character who wants to be seen and respected and valued as a person with her own thoughts and feelings and ideas, but she can't be any of those things, because she's not a person, she's a woman. and women exist to serve, not to live.

and so the only way to receive the acknowledgment and respect of her peers is to chase after a power she doesn't understand, enjoy, or necessarily even want, because at least if she suffers on the throne, she's suffering as a person, not as a mother to a son, a wife to a husband, or a daughter to a father.

like the entire show is a series of events featuring two women who aren't happy, attempting to win a game that doesn't care about them, in the vain hope that one day when they open their mouths, people will actually listen and care for what they have to say. and after all that grasping and pain and suffering and humiliation, it doesn't even work. because they're women.

#what if you made a show set in a world where women are oppressed and made to suffer and can never win#and you end it by showing your female cast face oppression and suffering. and then they don't win.#pretty quirky and cool right?#well then do i have a show for you!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anime Hot Take: Goblin Slayer is more offensive than Redo of Healer

I totally understand why the anime community is collectively freaking about Redo of Healer not getting cancelled by normies like Shield Hero, Ishuzoku Reviewers, and Uzaki-chan. A lot of anime content creators are saying because anime [social] cancellation is based on clout chasing and it’s because Redo of Healer is a bad anime, and I disagree completely because Uzaki-chan is also a bad anime. As excessively raunchy Redo of Healer is, its offensiveness has more narrative backing than Goblin Slayer does for its world-building.

Elephant in the room: depictions of rape are poor artistic choices when the physical act is shown instead of heavily implied for the narrative. Both Goblin Slayer and Redo of Healer depict rape onscreen to get more attention for being edgy and raunchy, needlessly. People finding Shield Hero more offensive for involving a false rape allegation are missing the forest for the trees and there is no rape in Ishuzoku Reviewers. Goblin Slayer uses its rape scenes to objectify people we’re supposed to see from the perspective of, very clearly. Meaning, Goblin Slayer is asking for a self-objectification in order for you to be invested in the main casts’ goals. The effect of this is Goblin Slayer is really only showing these gratuitous rape scene(s) for shock value. Goblin Slayer is a Fantasy, not specifically an Isekai Revenge Fantasy like Redo of Healer is. Redo of Healer uses its rape scenes to subjectify people we’re supposed to see from the perspective of, making it fundamentally different and more aligned with Game of Thrones depictions of rape than Redo of Healer. In episode 1 of Redo of Healer, the main character is subjectified, not objectified. In episode 1 of Goblin Slayer, the rape scene objectifies the woman. The only other conclusion hyperfeminism could have to this incongruity is media that portrays sexual violence is more acceptable when male sexual violence is on the forefront, which is fucked. In episode 2 of Redo of Healer, the first antagonist is a female and the rape scene itself is sick and cruel, but not gratuitous in the way Goblin Slayer handles its rape scenes. Again, the character is subjectified and not objectified, which makes a lot of difference if media makes the morally abhorrent but logical choice to depict rape for views because it works. Redo of Healer already starts on better footing than Goblin Slayer because a central theme in Goblin Slayer is the objectification of life and experience while Redo of Healer works in that same theme with the subjectification of people’s lives and experiences.

Redo of Healer is ultimately a power fantasy like most other Isekai are, Goblin Slayer is intended to make you feel powerless. There is some subtlety in the way the author puts forward the narrative of “power makes people bad” in Redo of Healer, while the narrative choices in Goblin Slayer directly portray the message of “no matter how much power you have, you cannot affect the world”. Both are a criticism of power fantasy, but Redo of Healer is actually within its genre doing so, not looking from the outside-in and acting above the genre itself when it has taken over the anime industry. The plot structure in Goblin Slayer reads as if it’s better than the Isekai trend, making itself pretentious and thereby worse than the trend because it’s just mocking something popular because it’s popular. Redo of Healer actually looks into why this popularity exists and if it’s legitimately warranted or just feeding the vanity of its readers. In the first two episodes, the narrative has all this suffering going on written in a way so the reader actively disconnects from the normally self-insert protagonist in an Isekai. Goblin Slayer literally does the opposite with Priestess. The self-insert scenes in Redo of Healer are actually the opposite because they structure themselves in that way but do the opposite, you don’t want to be in any of those situations. When you weigh moral wrongs and aren’t afraid of playing the oppression Olympics for the sake of philosophical conjecture, Keyaru is enacting retribution in a manner reciprocally efficient or less compared to what he endured. You can see that via his intended final act of retribution of Flare being to make her his consensual sex object rather than everyone’s nonconsensual sex object as he originally was. The finger-breaking was his exchange for the deception, involuntary servitude, and general lack of empathy; regrettably, the sexual assault with bodily harmful object was for the forced drug addiction via symbolism analysis. He ends up healing all this anyway and not being overwhelmed by it, meaning everything he did was a small fraction of what had been done to him. It’s still revenge, but it’s nothing nearly as crazy as what was done to him and actually didn’t drag out as much as people say compared to goblin rape scenes in Goblin Slayer (some of them which didn’t need to exist narratively and were only there because author is insulting your intelligence, assuming you forgot it’s a thing because it assumes you’re an Isekai reader). Fair warning about Blade and Bullet though is they represent very real tropes on the social spectrum, Blade representing hyperfeminist ideologies to the point of outright misandry and Bullet representing men who degrade themselves just for being men, so a lot more people will have something to be butthurt about when that narrative realization comes to pass. Part of the way Redo of Healer compartmentalizes its characters into said tropes speaks to a larger picture of what the show intends to do, criticize the Isekai genre and its tropes instead of just mocking them like Goblin Slayer does.

The narrative structure of Redo of Healer reads like a hate letter to Isekai power fantasy writing, the narrative structure of Goblin Slayer reads like a roast to Isekai power fantasy writing. Hate letters are generally more honest and genuine than roasts, which sacrifice truth for the sake of being comedic. Goblin Slayer itself wasn’t even that funny though, it had moments but its humor was so self-contained, it only existed if you already were self-involved enough in the tropes, in which you were the one being roasted. Effectively, Goblin Slayer seeks to roast you with no audience, making the roast itself kind of pointless and belittling. Redo of Healer though criticizes Isekai writing on two fronts: the morality of the world (which Shield Hero already did pretty masterfully) and the reasonable scope of a self-insert protagonist. Living in a morally dark Isekai world that’s full of hell and suffering is something Rising of the Shield Hero did so well, it would be difficult to see it done better, but Redo of Healer follows the exact narrative thread Shield Hero does only in a far more sinister way. The difference is Redo of Healer takes the grinding element from Cautious Hero and totally removes the opportunity for it to be had and the end result is said self-insert Isekai protagonist being abused in the party instead of valued, it actually makes sense on a power scaling level if you place it in a world where the characterization of all humanity is made out to be shitty from the start (slave trading demi-humans, raping other people for mana, rulers with no actual empathy or morality, etc.). Redo of Healer’s setting emulates humanity from Chapter Black in Yu Yu Hakusho. In simpler terms, if any of these dudes popularizing Isekai self-inserts into Keyaru, they’re not overpowered for no reason like in other Isekais, they’re overpowered because they were already humbled to the extent where nothing could ever feel like redemption. Most of these people self-inserting probably aren’t as great as they think they are, but especially on the moral scale. Keyaru represents a broken version of that self-insert: a human that is fallible, can feel real negative emotions and act abhorrently on them, and isn’t overly resilient for plot convenience’s sake. Keyaru’s immensely busted skill comes at a heavy toll, meaning it was balanced but he broke it (like Maple did in Bofuri) because he was driven to madness. If you break the “overpowered for no reason” trope in both harem and Isekai, you ARE a criticism of both. Are there good anime that use this trope well? Slime is an example. But Kadokawa specifically has been tending to favor titles that are criticisms of Isekai rather than straight-up Isekais themselves, making this something they were willing to push to the forefront even though it borrows a little too much from hentai plots. If anything, Redo of Healer shows how frustrated the industry, from writer to publisher, has been with the Japanese otaku community when poorly written, power fantasy, self-insert shows like Sword Art Online become the face of otaku culture and starts a predatory profit-seeking trend of everything has to be Isekai for it to make money. Redo of Healer reaches for a larger criticism of why anime storytelling has gotten less substantive in the past decade and plunges its hands into the depths of the filth and degeneracy that’s being promoted. It’s a meta-criticism to make what you’re putting out there so horrific it becomes nearly impossible to connect with.

Do I like Redo of Healer? No, absolutely not. Do I think it sends a loud and clear message to viewers who know how to analyze a piece of fiction with good depth and nuance? Yes. Goblin Slayer does not do that, Goblin Slayer itself is just an amusement park ride you’re supposed to enjoy, but they jolt you with shock value to get you invested, making its plot threads and themes gimmicky at best. Redo of Healer actually does what Goblin Slayer was going for in shock value and makes you so numb to it you actually realize how devolved Isekai storytelling is, adding its attention grabbing mechanism as short hentai clips like Ishuzoku Reviewers did. As for why Shield Hero was mentioned so much, it’s because the characterization of Blade specifically goes after those who were trying to get Shield Hero cancelled for its narrative thread. Blade is the worst representation of that, worship and veneration of femininity in a patriarchal context which ultimately results in the worship of power and existing power structures which promote said power to the point where queerness (in love of femininity) somehow excuses deplorability since postmodern queerness never actively promotes masculinity as something that can function as socially just. Flare, Blade, and Bullet all show more toxic masculinity individually in the first 3 chapters/episodes than Keyaru, and that was a deliberate writing choice. The reason why Redo of Healer isn’t actively being socially cancelled is because its biggest statement is “people are shit” and that’s an okay statement for normies.

Normies are coming after Nagatoro because it normalizes and almost makes light of real bullying. I think us weeaboos need to understand that bullying is a higher impact problem than rape being depicted in media if we’re fighting on the hill of “violent video games don’t encourage violence”. I find Nagatoro more difficult to understand the narrative intent of than Redo of Healer, the fact the weeaboo community is disconnected from that means we’re only looking at things on the surface level and are too within ourselves to know what real world problems actually have ripple effects on human behavior. The reason why we accept Nagatoro is because we know the two main characters eventually become involved and Hachioji could handle it to the point he consented to it. In pretty much all scenarios you have a mean girl bullying someone, regardless of gender, that’s not what happens: the person is left scarred, changed, and with significant platonic trust issues into adulthood. Rape is an issue that’s handled with so little care because of patriarchy and power struggles, people are generally far more numb to it than seeing actual mental and verbal abuse just being glossed over because “he’s a guy, he’s less of one if he can’t handle it”. Anime generally is going the way of Scum’s Wish where there’s more morally abhorrent characterizations of humanity than morally neutral ones, and all of these anime that stir controversy is a reflection of said fact. Having said that, Redo of Healer is willing to go way farther down into the abyss instead of just looking at it from the edge of the hole like Goblin Slayer does, then seeing scenes for shock value when you use telescope to look. For the reason Goblin Slayer thinks it’s above an Isekai while commodifying abhorrence to draw attention, I actually find Redo of Healer to be less offensive.

#Anime#Manga#Goblin Slayer#Redo of Healer#Rising of the Shield Hero#Ishuzoku Reviewers#Interspecies Reviewers#getting cancelled#offensive#rape#objectification#hyperfeminism#shock value#subjectification#power fantasy#Isekai#power dynamics#power scaling#morality#self-insert#chapter black#Yu Yu Hakusho#overpowered#that time i got reincarnated as a slime#otaku#Sword Art Online#don't toy with me miss nagatoro#weeaboo#bullying#Scum's Wish

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Legacy of Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo is a Mexican born artist formerly remembered for her paintings, more specifically her paintings based on nature and Mexican culture as well as her many self-portraits. Kahlo took up painting whilst recovering for a bus accident she was in as a teenager, the accident left her in a full body cast for quite some time and painting was her way of distracting her from the pain of recovery. Her work is heavily inspired by her culture which she incorporates in the clothing and scenery that she depicts in her paintings. In her lifetime she completed over 140 paintings (55 of which being self-portraits). A common theme in Kahlo’s work is both physical and emotional pain, the physical pain coming from her multiple surgeries she had to undergo because of her accident and her emotional pain came from her rocky relationship with her husband, fellow artist Diego Rivera (who she married twice). Despite that Kahlo is recognised as one of the greatest artist Mexico has ever seen and has become on of the most widely known artist in the world.

Kahlo was born in Coyoacán, Mexico City on the 6th of July 1907 and her full name is Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón. Kahlo’s father was a photographer who immigrated from Germany to Mexico where he met her mother Matilde, she is the third child with her two older sisters Matilde and Adriana and her younger sister Cristina. Even before her accident Kahlo had problems with her mobility as she contracted polio at a young age that damaged her right foot and caused her to have a limp from the age of six. In 1922 Kahlo became one of the only female students to attend the renowned National Preparatory School in which she became very politically active and joined the Young Communist League and the Mexican Communist Party whilst still a student. Not long after (1928) she married fellow artist Diego Rivera in what would become a very rocky and unstable relationship going through several periods of separation and rekindling, it was this relationship that would inspire some of her most famous paintings.

Kahlo first exhibited her work in 1939 in an exhibit in Paris, her work received massive praise and not long after Kahlo was commissioned by the Mexican government for five portraits of important Mexican women in 1941, however she was unable to finish the project due to the passing of her father as well as her chronic health problems. In 1953 Kahlo got her very first solo exhibit in her home city and, despite being bedridden, she refused to miss the opening and arrived by ambulance to celebrate with attendee’s. After Kahlo’s passing in 1954 her work became the symbol for female creativity and helped fuel the feminist movement in the 70’s, it was such events that has made her artwork iconic. “Frida expresses her own experiences in her works, it is exactly what she is living in her present, how she interprets it and how she believes that others live it. She paints after her divorce, as already mentioned before, “Las dos Fridas”, which we can locate within Surrealism (1939), because the surrealists do not want to copy reality but prefer to capture their reality, which is what they interpret of her dreams, or in the case of Frida, her own experiences, since she was able to create wonderful works from them. (…) Frida differs from the surrealists because she does not pretend to paint her dreams or liberate the unconscious, but through the technique of surrealism expresses her own experiences, which emanate suffering.” – Galeria Valmar, artes visuals, 2019.

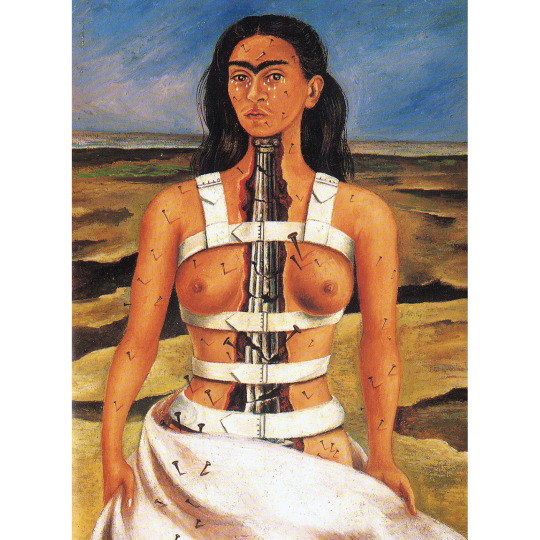

The Broken Column

For this next part I wanted to analyse some of Kahlo’s most famous paintings and explore the deeper meaning behind them, starting with ‘The Broken Column’. ‘The Broken Column’ was a self-portrait created in 1944 shortly after a spinal surgery Kahlo underwent due to her accident, the surgery left her in a full body cast and a spinal brace which can be seen in the painting. Also in the painting we can see her body appearing almost cut in half, as if her spine had been ripped out, as well as nails poking out of her body. This actively demonstrates the physical pain constant years of surgery has caused Kahlo with the nails being a physical representation of such. Through the centre of her body the column taking the place of her spine is broken in several places creating the effect that it’s about to crumble and collapse on itself. Almost all of Kahlo’s self-portraits are meant to display her suffering caused by her accident, which left her both unable to bear children and ended her dreams of becoming a doctor, this is often shown by her facial expressions with ‘The Broken Column’ being no exception. After a closer look you can tears falling down her face as well as strong highlights in her pupils to emphasise the physical and emotional pain she was suffering. “The Broken Column was painted shortly after Frida Kahlo had undergone another surgery on her spinal column. The operation left her bedridden and “enclosed” in a metallic corset (…) The accident ended Kahlo’s dreams of becoming a doctor and caused her pain and illness for the rest of her life. (…) Although her face is bathed in tears, it doesn’t reflect a sign of pain. The nails piercing her body are a symbol of the constant pain she faced.” – Zuzanna Stanska, The daily art magazine, 2017.

Some people also believe that this painting is not just a representation of the pain Kahlo endured because of her health, many believe that it is also a commentary on the emotional pain caused by her unstable marriage. Most of the Kahlo’s most iconic pieces are inspired by her suffering and serves as a visual representation to her inner thoughts and emotions, her marriage being a large source of suffering throughout her lifetime. Some view the fragmented column lodged in her chest to be fragments of her marriage impaling her. “Despite the somewhat in-your-face symbolism, this is a favourite subject for bad art theory papers, identifying the column as everything from her fragmented marriage to a giant phallus penetrating her body. While such interpretations could be partially true, we think that sometimes a spinal column is just a spinal column (…) She referred to her medical ordeal as her “punishment.” She also took her tragedy in good humour, saying of this painting, “You must laugh at life...Look very closely at my eyes...the pupils are doves of peace. That is my little joke on pain and suffering…” Some claim the larger nails over her heart reflect her tortured relationship with Diego Rivera.” – Griff Stecyk, Startle, 2019.

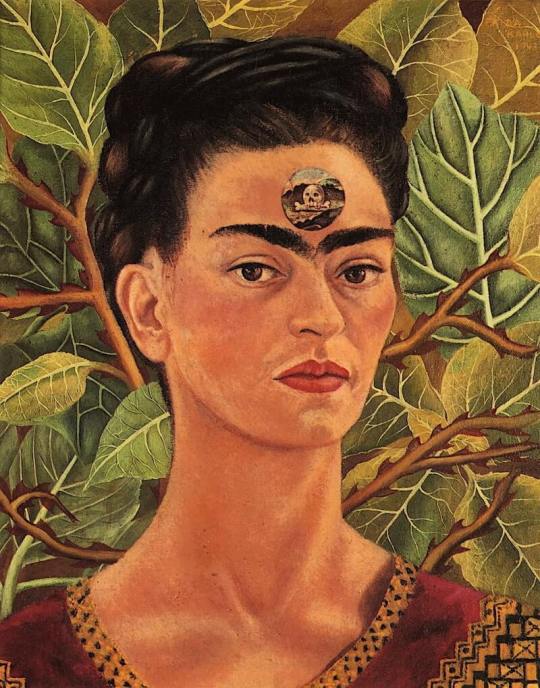

Thinking about death

The next painting I have chosen to analyse is titled ‘Thinking of Death’ which is a self portrait created in 1943. This painting was created around the time Kahlo’s health really began to deteriorate as it depicts herself surrounded by nature with a small skull in her for head. Kahlo painted herself in very traditional clothing with her hair done up in a bun. The skull depicted in her forehead is supposed to represent the fears Kahlo had due to her health battles, with how sick she was death was a constant thought for her with it having come so close multiple times in her life. In Mexican culture death can mean the rebirth of life with is meant to be represented by the lively green leaves behind her as well as her facial expression which shows no sign of fear or panic suggesting Kahlo’s acceptance of death being another part of life. “Due to her poor health condition, death is an inevitable thought which lingering over her mind. In this painting, death is symbolized as skull and crossbones which shows up in her forehead. In ancient Mexican culture, death also means rebirth and life.” – FridaKahlo.org, 2017.

The skull itself represents the thought of death and sits right were ones third eye would be, this suggests that maybe Kahlo views the thought of death as some kind of wisdom instead of a fear, although Kahlo never wished to be labelled as a surrealist artist as her paintings come from her reality. “In Kahlo’s collective work, death seems to pervade almost every one of her paintings as an expression of pain, or a motif of oppression concerning female gender roles. Kahlo employs an almost anatomical eye in looking at her form, juxtaposing it beside images of adorned skeletons.” – MaryFrances Knapp, Seven Pounds, 2017.

Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird

The final painting I have chosen to analyse is titled ‘Self-portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace’ which is another self-portrait completed in 1940. In this painting Kahlo is surrounded by animals such as a monkey and a black cat with a large necklace of thorns around her neck, in the thorns there is a hummingbird tangled amongst them. She is also surrounded by green leaves much like ‘Thinking about Death’ with insects like dragonflies and butterflies in her hair, with a blue sky barely peaking behind the leaves. The painting was completed soon after Kahlo’s messy divorces with Rivera following the theme of suffering throughout her paintings. The thorns around her neck could be a visual representation of how it felt to grieve her relationship much like the nails did in ‘The Broken Column’, though it could have a religious meaning referring to Jesus’s crown of thorns. Kahlo also incorporates Mexican culture into this piece with each animal representing something different that is relevant to the context of the painting with hummingbirds symbolising love, black cats symbolising bad luck, Dragonflies symbolising prosperity and monkeys symbolising lust. “This self-portrait was created following Kahlo’s divorce to Diego Rivera (…) There are obvious religious overtones to the piece using Jesus’s crown of thorns. Kahlo has painted herself as a Christian martyr, enduring the pain of her failed marriage (…) In Mexican culture, hummingbirds signify falling in love and are used in love charms (…) Kahlo often used vibrant flora and fauna as backgrounds for her self-portraits, to create a claustrophobic space teeming with fertility. It is thought that the emphasis of her monobrow and moustache – with the lines of her eyebrows mimicking the wingspan of the hummingbird around her neck – was intended as a feminist statement.” – Tara Lloyd, Singul art Magazine, 2019

This painting is a great look into Kahlo’s attention to detail and how every piece of her paintings represents something, she is very in touch with her culture and has great understanding as how to show her emotions and life experiences in each of her pieces. “Like many other of her paintings, this artwork is a lot akin to a painted assortment of symbols. Every element in this painting gives specific clues to Kahlo's mental state, perhaps none more than her still, direct, emotionless gaze that seems to express the immediacy of her pain.” Audrey V, Wide Walls, 2018

To sum up everything thus far Frida Kahlo is an incredible artist who poured her life into her work, her pain and passion has made her paintings so iconic in this modern age. She has become a symbol not only for Mexican artists but female artists as well, paving the way for many like her in the years to come. In response to why she painted so many self-portraits Kahlo responded, “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best”.

Bibliography

Galeria Valmar, artes visuals, 2019

Zuzanna Stanska, The daily art magazine, 2017.

Griff Stecyk, Startle, 2019.

FridaKahlo.org, 2017

MaryFrances Knapp, Seven Pounds, 2017

Tara Lloyd, Singul art Magazine, 2019

Audrey V, Wide Walls, 2018

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please Lorna tell me more about Six!!

LISTEN SIX IS FUCKING AMAZING

I saw it on Wednesday and it was!!! So good!! Even better than I imagined and I cried twice it was that good and honestly? By the end of it I felt so powerful and pumped up and I just felt so alive and glad that I was woman. It made me proud to be female to see this amazing show about these amazing women re-writing history to carve out a space for themselves in a historical record that’s largely overlooked them, or else reduced them to stereotypes (which the show then goes on to SMASH over the head repeatedly with a hammer).

Catherine of Aragon? Actual QUEEN of my heart that deserved so much better than to get dumped after quarter of a century of marriage and was punished for her lack of ability to bear a son (because in those times the sex of the baby was believed to be the responsibility of the mother) and eventually turned that punishment inwardly on herself, coming to hate herself because she thought she’d failed Henry. Plus Jarneia is such a BEAUTIFUL and TALENTED actress and performer and CoA’s costume is also A+++

ANNE BOLEYN. MY FAVE. Listen, going into the performance Don’t Lose Ur Head was my least favourite song but my opinion was completely transformed once I saw it. The acting, the expressions, the emotion and playfulness but also the sense of impending doom that Millie O’Connell brings to the role is so watchable and fun and makes you feel for Anne, who got into a situation far beyond her control and was punished for speaking her mind and trying to maintain some sort of independence as things got serious really quickly and she felt out of her depth. Also, the “I guess he really liked my head….” joke made me pee myself.

Jane Seymour. I saw Courtney Stapleton as Jane and she blew me away. She has a fierce tenderness to her that comes through in the raw emotion of Heart of Stone, and her speech which is the intro to the song, talking about her deep regret that she had to die and leave her infant son at the mercy of his turbulent father and jealous, power-hungry uncles. The saddest part is that Edward VI himself died very young as he had a lot of health issues, so no-one in that family got much of a happy ending.

Anne of Cleves. LOVE OF MY LIFE ANNE OF CLEVES. Get Down is my favourite song, I listen to it constantly and it’s such an anthem? For all girls who were made to feel like they didn’t mean anything or didn’t deserve respect because they had average or below looks. SIX Cleves is so sassy and embraces her unconventional attractiveness, not allowing it to sway her into being dictated to by men. She gets the last laugh in the end and it’s marvellous.

Katherine Howard. I WOULD KILL EVERY SINGLE MAN ON THE PLANET FOR KATHERINE HOWARD. She’s stereotyped in history as the teenage whore who seduced the ageing King Henry, but what the history books don’t tell you is that she grew up in what was basically a brothel, and being considered beautiful from a young age meant that she was the target of a lot of inappropriate attention from older men. She was taught that this was normal for a girl of her beauty and maturity, and that she should welcome and even encourage it.

Taken advantage of and groomed from the age of 13, All You Wanna Do is the most disturbing performance in the show and as it reaches its climax it makes your skin crawl, as Katherine is groped on-stage by the girls to symbolise men’s wandering hands and the unsolicited sexual advances that were pushed on her and that eventually got her labelled as a slut….and beheaded.

And finally we have Katherine Parr. She’s the one who first points out that competing with each other for ‘who had it worse’ is so incredibly wrong and unfair, and in fact is basically furthering the misogyny that has kept them from being treated as individuals in the historical record for centuries. At one point, Catherine and Anne are arguing about how many miscarriages they suffered (Anne had two confirmed miscarriages, Catherine had five) and Parr is horrified that they’re using their past abuse and trauma as a way to one-up one another when they should be supporting each other because Henry was a dick to all of them.

There’s a really powerful message here about supporting women and holding each other up instead of trying to make it into a competition of ‘who has the worst time?’ and working together to bring down the oppression that we face as women - all kinds of women. This is further exemplified by the fact that, in the performance I saw, half the cast were WOC. In the original SIX cast, 3 of the 6 actresses are also WOC - Aragon, Cleves, and Parr were all played by black women. Two of the alternates are also WOC (Courtney Stapleton and Grace Mouat). The theme is that these six women are lumped together as ‘the wives of Henry VIII’ and not much depth is given to them beyond that.

Catherine of Aragon had issues with her fertility and reproductive health, hence why she struggled so much to conceive.

Anne Boleyn was pushed by her father to boost her status in society by getting her foot in the door at the royal court.

Jane truly loved Henry, but died before she could really get to live out her life.

Cleves ended up with a huge mansion and more money than she could ever spend, which she gladly enjoyed as a way of getting the last laugh for being rejected for her ugliness.

Howard was eighteen when she was executed. She was ten years younger than her youngest stepdaughter, Elizabeth.

Parr married multiple times because it was the only way to avoid being cast out of society as a sad lonely spinster, shamed for not having a husband. She was also the first woman to publish a book under her own name in the English language.

If you want to feel seen and heard and validated as a woman, you need to see/listen to SIX. It’s the perfect show for you. It’s sort of like the Wonder Woman or Captain Marvel of musical theatre. You’ll love it.

I didn’t think that a pop-rock musical about Tudor history would take over my life like this, and yet here we are. Sorry not sorry etc ;)

#aaaand i rambled for like 50 years because i love SIX!!#six the musical#justasmallbloginabigklainefandom

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Many believe that the show is racist, with the killing of POC and especially making MOC be in dysfunctional/ blaming relationships with white women e.g. Bell+Octavia, Ilian+Octavia, Wells and C maybe even Jackson and Abby with the bland storyline of being her shadow for 5 seasons. What is your opinion on this matter? I believe the show definitely needs some more well-rounded POC, especially with Shaw most likely being killed off (Jordan says no comment on an ig live about being on t100).

You don’t get much more well rounded POC characters than you do on this show. Do you know what “well rounded” means? Because your ask tells me you don’t. Well rounded is not a problem for the POC characters on The 100. They get to be the heroes, the romantic leads, the diplomats, the peacemakers, the villains, the zealots, the best friends, the geniuses, the sexpots, the victors. They get to be sad and happy. They are the martyrs and they get the happy endings. They have complex character development and are posed as sympathetic characters that the audience can identify with. They have internal lives and backstories and goals and sorrows and loves.

I like the representation of POC on this show and the roles are multidimensional, juicy, important and non stereotypical. I feel represented as a mixed race latina, particularly by Raven and by Bellamy. Are you telling me they aren’t well rounded?

Characters on this show die off. That’s the kind of show it is, regardless of their race. If you want representation where there isn’t suffering, you need to find a show that is not about survival or tragedy. This one is. That doesn’t mean it’s bad representation. There is a REASON to watch this kind of show with suffering and disaster. It is NOT a feel good show, so if you’re looking for that, nothing on this show will feel right to you. This is the wrong place to look for happy POC characters. Because it is not a happy show.

I take issue with some fans description of interracial relationships as racist. Octavia was a character in crisis. An abused child becomes an abuser. That’s how the cycle of abuse works. She was born in a world that was extremely oppressive and terrorizing and this affected her, and then she was adopted into a world in which violence was the answer. She wasn’t racist. Racism is LEARNED behavior. A child who grows up with only two people, one of whom is POC is not going to be racist. That’s not what that is. To SAY that Octavia is racist because of how she treats her brother and boyfriend simply because she’s white and they are not, is to say that racism is inherent in white-non white relationships. And it also says that mixed race families and interracial relationships are ALSO inherently racist. Because that is the only way that white and non white people can have relationships. It says that love between white and non white people is inferior, because race is more important than people. I find this position to be EXTREMELY offensive and racist, as a mixed race person who has lived al her life in mixed race communities and been in many interracial relationships. It is actually a white-supremacist position and is called anti-miscegenation. Yes. I question when people find mixed race relationships offensive.

Not only that, but you’re defining relationships where we didn’t see any such dysfunction and saying those are both dysfunctional AND racist. And that means you are making up proof to fit your theory where none exists.

Clarke realized she was wrong about Wells and asked for forgiveness. After a few days. She had not talked to him in a year because she was in solitary confinement. That makes it a fight, where she was in the wrong. Are you saying that this is an abusive dynamic? Why? Because Wells was black and she was white?

Perhaps you also don’t understand dysfunctional relationships, if you think that having an argument is dysfunctional and racist. And to tell the truth, “blaming relationships” isn’t a thing. At all. You made that up.

Jackson has a bland storyline because he is a TERTIARY character, not because he is a POC. Harper is also a tertiary character. Don’t see you complaining that she was following Monty around. Again. Made up. And showing a distinct lack of understanding for how you tell a story and what a main character is compared to a supporting character.

You’re also deciding Shaw is dying when we know no such thing at all. That is not evidence, or any kind of support for your theory. That’s also made up.

I think this show has a fascination with white female badasses. There’s a blindspot there. We are all part of a racist society and need to examine our own racism that can easily go into play. The 100 TRIES to I think. Sometimes they miss stuff and fall short. I don’t watch shows that I think are racist because racism offends me. I don’t find this show racist, and I AM LOOKING FOR IT. It is still a fantasy story and they don’t directly address current day stories, but they do address the concepts within the conventions of the genre. This is not racist, it is the genre. That’s the way this kind of story is told. if some of the things they do bothers some people, they probably shouldn’t watch it.

I like the POC representation on this show. I like that a large portion of the cast is mixed race like I am. Some of whom fandom only sees as being white or only sees as being POC. A lot of the actors come from mixed families and they cast like that on purpose. (Bob, Lindsey, Ricky, Jarrod, Ian, Luisa, Dichen, Nadia,) And as a mixed race person, I like it.

The fandom however has told me that what I want to see for my representation doesn’t matter. Whether I speak about being mixed race or about being Latina. I have been told, by white people and POC people alike, that I have no say in my own representation. I have been told that I am too lightskinned to speak as a mixed race POC, and also that I didn’t know what good representation for latinas was. That means that the fandom itself has both silenced and whitewashed me as a POC, in a way, that when someone does it to Bob, the same people call racism. Is it not racist when they do it to me? It’s okay because I disagreed with their meta about MY representation? IDk.

So you’ll forgive me if I don’t jump through the hoops of your demagoguery. Fandom isn’t always as well informed as they think they are. Like this ask, you show a lot of ignorance and a lot of assumptions and make accusations without proof. You are practicing confirmation bias by cherry picking inaccurate details to prove a point and ignoring details that disprove it.

I also question your motives in sending this ask because I feel like you’re trying to start some sort of controversy, so I have two options. Stay silent, or speak up about my feelings and experience as a mixed race latina in this fandom, and the racism I have experienced here. Which gets called “playing the victim” whenever I point it out.

Ugh all in all this ask is a mess and points to a lot of problems in fandom. You want to fight I think? Or just call the show bad/racist? So you’re making up shit? You want me to say something to get myself in trouble with people I have been staying away from for a year very happily?

Or are you listening to other people making up shit and because they’re using emotional trigger words you’re just taking what they say at face value without questioning them or looking farther into them?

#ugh i didn't even want to post this if i start getting hate i'm blocking it all#can y'all just let me enjoy my favorite show without having to defend myself against whatever new outrage you're making up?

19 notes

·

View notes

Link

After 20 years of friendship, I’m finally starting to talk about intersectional racism with my white best friend.

Not racism in a metaphorical way. Not racism like: “Hey, did you happen to leaf through that Ta-Nehisi Coates book I left on the coffee table?” Not racism like: “Wasn’t that Margaret Cho joke so dead-on?” Racism like: “I need you to acknowledge our lives aren’t the same.”

For a long time, I pretended our lives were the same. Sarah (name changed) and I went to the same politically radical college, where we first bonded over our love for practical joke-oriented performance art, cooperative living, and television. She goes to racial justice meetings and founded an arts residency for social justice. Now, Sarah works at an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse hospital. But (and this is a duh) none of this means she will ever completely understand lived-through racism, and its impact on me.

In college, where we bounded across campus discussing Marxism with pine-scented oxygen in our lungs, noshing bagels on the sunny quad, and baking bread in our cooperative house together, it was easy to pretend that Sarah and I were equals in the eyes of society — even though an unconscious part of me always knew that we weren’t.

For starters, there were the basic economics. Sarah’s parents procured internships for her at prestigious museums, took her skiing in the Alps, and spoiled me like I was their second daughter. My parents, meanwhile, hadn’t been to a museum in years, and their idea of leisure as immigrant restaurant owners was sleeping more than six hours a night.

It was easy to pretend that Sarah and I were equals in the eyes of society — even though an unconscious part of me always knew that we weren’t.

But there were also racial inequalities between Sarah and me. When I moved to a small white rural town in the Catskills to live with Sarah, I discovered how hard it was for a politically radical person of color to fit in. While some of my new acquaintances were friendly, others were outright hostile when I talked about cultural appropriation. I was told wearing a sombrero at our Halloween party was not cultural appropriation because cultural appropriation is a relic of the past in our post-racial millennial society. When I asked why there were no local anti-Trump protests, I was told that our town was indeed doing activism, but in a grassroots way (read: nothing that changed the status quo). I soon considered moving away as soon as possible, but didn’t have enough cash yet.

Shortly before my departure, the kraken was unleashed: When I posted “I don’t like the way Kimmy Schmidt portrays Asian-Americans,” a white friend of Sarah, Lucy (not her real name), sent me a long, angry, macroaggressing email. Lucy informed me that I was not Asian, because race did not exist. “Like it or not, we are all Americans,” Lucy lectured. (I checked my skin: yup, still Asian-American.) Lucy told me she was “tired of everything being about race” and the “intolerance of the PC Police.” (I’m guessing that’s me.) Since the election, Lucy said, “now is not the time for more divisiveness.” (I didn’t draw these lines.) Erasing my lived experience, Lucy declared, “Now is not the time to look for problems, when they might not be there.” (Good to know racism is the Boogeyman.)

#NotAllWhitePeople, The Quiz Ask yourself if you can honestly say ‘No’ to all of these questions.theestablishment.co

Furthermore, Lucy understood marginalization, she claimed (not sure she gets what marginalization is). “If you are sensitive to your identity as a person of color, or think that you have been treated as ‘the other,’ consider what it feels like to be singled out as a white person,” she wrote, emphasizing how hard it was to have been accused of racism by her more privileged white friends in the past. She went on to equate my marginalization with being ostracized by her conservative family when she became a “lefty hippie punk liberal.” Lucy wrote that she “felt this deep oppression and lack of acceptance from my family. So I do know what it feels like to be marginalized. Being white doesn’t bring about automatic privilege. We all have our own difficulties, problems and stumbling blocks in life.”

My entire body shook with rage and sadness at the “#notallmen”-style ignorance of the email from a supposed feminist. I knew that she had told multiple friends that white privilege was not real, despite well-researched scientific evidence to the contrary. I couldn’t work or write for a week, disillusioned by the reality of pervasive ignorance in my country. Friends’ replies made it worse — some of my white friends told me they thought Lucy had a valid point in showing she understood racism because of the anti-Semitism her family had suffered.

I wrote Lucy a simple, short email asking her to read about white privilege online, and to get Cornel West’s book Race Matters, because without some fundamental agreements, we weren’t even going to be able to start discussing issues this deep — it would simply be a “yes” versus “no” fight. (She ended up responding, but in lieu of addressing my points, just said I’d always avoided her at parties.)

A couple months later, I finally escaped back to Brooklyn with a sigh of relief, surrounding myself with Asian-American friends and thinking hard about race. But during a one-night visit back to Sarah’s house in the Catskills, I discovered Lucy was coming to dinner. I didn’t want to sit through a dinner party, much less a five-minute chat, with her, and I tried to explain to Sarah that I didn’t want my one night with her to be five hours with Lucy. Sarah said the power wasn’t hers, because her boyfriend had invited Lucy as his guest, and to just try to get along with Lucy because she was her friend too. Sarah had heard about the message Lucy had sent before, but she had not seen it, and she hadn’t asked questions to dig deeper into how it had hurt me. Now, I went into shock at her blasé response.

I spoke not more than three words to Sarah or Lucy during all of dinner — and anyone can tell you I’m usually the chatterbox of the table. Sarah didn’t even seem to notice my intense sadness, which made me even sadder.

Despite our closeness, I realized that Sarah and I lived in two different worlds and probably always would. It was no longer something I could ignore, struggle as I might to keep those rose-colored glasses on by their dangling frame. I fell into a deep depression. A week later, not knowing what else I could do, I opened up my laptop because I was too afraid to call Sarah (and as a writer, I express myself best in words). So nervous that I would alienate my beloved best friend of two decades that my eyes filled with tears at just the thought of no Sarah in my life, I wrote her a letter that changed our friendship forever.

Despite our closeness, I realized that Sarah and I lived in two different worlds and probably always would.

How do you talk to your white best friend about race?

Imperfectly, stumblingly, emotionally, but with honesty and the hope that you can reach one another across the gigantic divides of systemic American racism. “I want to have a real and true friendship with you, not one where we don’t discuss race,” I wrote. “I live in a world that is different from yours, and I need you to understand that. I have been called racist names on the street and in schools my whole life; I need you to acknowledge that as my best friend. I have gotten emails like this my whole life. It is a lot. I am tired and exhausted. I would like you to support me if you can.”

With truth, revealing all the things you hid from her so she wouldn’t see the ugliness in your life, the shame at what you’ve endured even though it’s not your fault. I tell her about age 11: the girl who made slanted eyes at me between each song in band class, forcing me to grit my teeth and try to focus on the sheet music even as tears blurred my vision. Age 12: the white female bully who slapped me across the face in middle school and called me a “chink,” but who I was too afraid to report to the principal. Age 13: my father came home from the ER with broken ribs because he got into a fight with a man who called him a racist name at the chemical plant. 15: the drama director doesn’t ever cast me in a speaking or named role because I’m not what you’d picture in Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, even though I’m more talented than the other contenders. I sit quietly in the back of all crowd shots. 16: the sullen boy who tells me the only reason any guy would date me is to use me for sex “like a hooker” and then dump me to marry a white girl. 17: my white Jewish partner’s mother tells him she doesn’t want “yellow” grandchildren. 18: my teacher tells me math should be easy for me because I’m Asian, so I don’t ask for help (even when I’m desperately drowning), and I end up getting a C-. 20: the Korean guy I’m dating asks me to introduce him to a blonde American girl he can date when I finish my study-abroad program and leave Korea. 21: the man on the street who tells me he wants to make me his Hiroshima bride and eat my “slanted pussy” — not because he thinks his tactics will work, but because he wants to show me who has the power. Welcome to New York! 35: the white liberal New Yorker friends who are shocked and disbelieving when I tell them I have to shield myself from doubly racist and sexist comments on the street every week — yes, in cosmopolitan New York; yes, in 2017 — because it is not their experience and they simply can’t imagine New York is that racist. The fact that I even feel like I need to provide specific evidence of racism to them galls me.

Let’s Stop Pretending White People Can Be Objective On Racial Issues theestablishment.co

It is so cathartic even to write these words to Sarah. I suddenly feel like the tea party in Mary Poppins — am I floating to the ceiling, and will Sarah join me there?

She responds empathetically, stating that “if (Lucy) says anything to me or in front of me that I perceive as willfully uninformed or racist, I will be calling her on it. If it is a fight where she isn’t willing to listen to my side of the argument, she and I will have the same problems that you and her have had, which would lead me to reconsider our (hers and my) friendship. I love you and I NEVER want to behave in a racist manner towards you or anyone.” She asks me to keep sending her links to articles about white privilege and lived racism.

The next time Sarah and I talk on the phone, I feel not only relieved, but that much closer, like our best friendship found a reserve well beneath its surface that we both didn’t know existed, and we’re now both drinking as much water as we can. It’s not perfect, but it’s a beginning. I believe Sarah truly cares about me and will stand up not only for me as a person, but for other people of color who do not have the agency and privilege that I carry as an educated, light-skinned non-black person of color.

It’s not perfect, but it’s a beginning.

It may be frightening to talk to your white best friend about the racism you face, but the alternative is a splintered existence and a constantly code-switching friendship. For a long time, I euphemized my speech about racism as carefully theoretical and philosophical to protect against the white fragility of my friends. I operated under the premise that Trump supporters, not the people sharing my table, were the only racist ones.

Readers of color, it’s better to have extremely difficult talks in a real friendship than to ignore the issues and pretend they don’t exist — all the while feeling alone, unhappy, and confused privately. You are actually doing your interracial friendship — and, IMO, the world — a disservice by shielding it from reality. Your dialogues may or may not synthesize into a lasting friendship, but somehow, a change has got to come, and one potentially fertile ground is in our interracial friendships.

We live in different nations, experiencing different treatment and speaking different languages. But now I know Sarah is listening to my language.

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

okay but my get down thoughts:

Because it’s almost Monday and I have seen NONE YET.

Behind a cut because spoilers abound (and that’s a sentence I don’t think I’ve written since 2009).

- First and to get this out of the way, it is DEEPLY troubling that in a show that’s supposed to be as diverse as it is and as representative of hip hop/disco culture as it is, The Get Down has positioned all of its darker skinned characters as the most morally corrupt (Fat Annie, some of her gangsters, Cadillac to a certain extent) or corruptible (Cadillac again, Shao, Boo Boo, Yolanda if you count her attack of morals as the disloyalty it’s presented as).

Meanwhile, the lightest skinned characters - Zeke and Mylene - are about as incorruptible as it’s possible for them to be. Ra-Ra is also, without question or contest, Good. And while Dizzee sits in a similar space, his queerness also removed him from much of Part Two’s larger narrative in a way that was both magical and also did a huge disservice to his character.

- To continue in this vein, the fact that the only major Black female lead is Fat Annie is appalling. By her very nature and name, Fat Annie is a product of fatphobic stereotypes. Adding to that, she’s dark-skinned which perpetuates negative, colorist and anti-Black ideas that deliberately attack dark-skinned Black women and contribute to their continued oppression. She’s both positioned as kind of a mammy (with her creepy mommy schtick) and a hypersexualized predator (with her rape-y everything else), delivering a one-two punch that combines two of the most harmful stereotypes about Black women into one nasty character. And as one of, if not the ONLY, irredeemable villains of color on the show (one can argue that even Mylene’s father who we saw brutally beat both his wife AND daughter was positioned as empathetic in the end after the truth dropped and he killed himself), she’s aligned within the narrative with the likes of the Yale and Yuppie racists rather than being given the same nuance and empathetic treatment as the rest of the POC cast.

- Last major complaint is also tied into something I really enjoyed about the series as a whole, and loved seeing played out again here: I needed more Dizzee and Thor and queerness in general. And I’m genuinely torn on this because I absolutely adored the comic book motif and the fact that Dizzee is the heart of the story - made sweeter by the fact that he, himself, thinks it’s Boo-Boo - means SO MUCH TO ME. I thought the exploration of this beautiful, bisexual alien was wonderfully done and minimalist in a way that worked but also edged along the line of “we’re too cowardly to actually explore non-heterosexuality in the same way we explore heterosexuality”. Dizzee and Thor’s relationship plays out in visual metaphors. And even the moment when Dizzee and Thor confess their love to each other happens in a drug-and-dream state that doesn’t actually exist. I don’t know that I needed a cut-to-black sex scene, but I wanted at least ONE concrete moment between the two of them that wasn’t just Dizzee painting a stripe down Thor’s face (which was STILL SO LOVELY). Also, you don’t get to make Dizzee the heart and soul of your story, give him a grand total of 30 minutes screentime (and that’s being GENEROUS) and leave us on that kind of cliffhanger. That’s just emotional manipulation.

- Speaking of queerness, though, I LOVE the motif of Queer Spaces as Safe Spaces in The Get Down. Though there are Black spaces that are safe, not all of them are. On the flip-side, I think all of the queer spaces we see in The Get Down are presented as welcoming, warm, restorative, and transformative. From the club Thor takes Dizzee to at the end of Part One, to Ruby Con - which is only made unsafe by Mylene’s militantly religious father’s invasion - to Jackie’s apartment in the finale, and even Thor and Dizzee’s crash pad/love nest, queer spaces are presented in a way that reminds me of how it feels every time I walk into a gay club or bar. I do wish we saw these spaces as more diverse because there’s something unsettling about how they seem predominately white, but there’s something so special about the fact that the two most open and supportive and magical environments our main characters find themselves in are The Get Down, and queer clubs/homes. It’s also historically important to the history of disco that these queer clubs are vital to the growth and development of Mylene’s career.

- MORE ON QUEERNESS BECAUSE CAN WE TALK ABOUT SHAOLIN FANTASTIC FOR A SECOND? So after Part One, we all were like “Shao, you’re obviously in love with Books, come on, son.” But Part Two leaned HEAVILY into this subtext. I wish we’d gotten something more resolute out of it (again, I don’t know if it was cowardice or what) but I will say the development of the subtext was still really emotional for me. First, there’s Shao’s obvious jealousy in the first episode. This isn’t anything new, but it’s blatant and almost uncomfortable to witness. And then, after the show at Les Inferno when shit hits the fan, things get real. Mylene confronts Shao and during their horrible, ugly fight she finally brings up what’s been lurking under the surface about Shao’s possible feelings for Zeke. Shao says “I ain’t no f****t” because of course he does, and she tells him to get his own man. And then he says more horrible things to her because Shao is kind of a terrible person and it turns out, queer or not, Zeke is basically the only person Shao loves or has probably ever loved.

But queer or not? That’s the question. WE DON’T KNOW. One super significant, absolutely beautiful scene to me was when Shao realized where they could find Dizzee and tracked him to the crash pad/love nest. This is where I think we could’ve at LEAST seen Dizzee and Thor in a more compromising position but either way, Shao walked in and knew exactly what was up. Even before the tag to the scene, I thought it was incredibly significant that of all the characters to find Dizzee alone (by entering not only a literal queer space but Dizzee’s very queer narrative), it was Shao. But the tag is lovely, with Shao essentially designating himself as a safe space for Dizzee and validating Dizzee’s sexuality. This from the one character who uses the f slur the most out of anyone other than, perhaps, Cadillac. Which may or may not be purposeful and significant (but is certainly as annoying and hurtful in Part Two as it was in Part One).

Also I have to say here that I don’t know if I’m mixing up Shao’s story with Todd Chavez in BoJack Horseman (which I also just binged) but I feel like there’s a moment in Part Two where Shao implies that his romantic/sexual life and/or understanding of sex/romance is stunted because of what Annie did to him. This obviously doesn’t mean he’s queer, but if this moment happened it does indicate that Shao’s never really had the chance to figure out what he is. Either way, we see exactly how much his trauma has affected his relationship with Zeke during their breakup. Later, when Annie threatens to kill Zeke she refers to him as Shao’s boyfriend. It’s an attempt to emasculate him, but Shao’s response now - rather than saying he’s not gay - is to say that Zeke’s not his “fucking boyfriend” in a tone that’s at least as defeated as it is defensive.

There’s something innately Other about the way that Shao’s feelings for Zeke are framed and that’s been the case from the beginning, but combined with some narrative play and the way third parties are starting to respond, it’s pretty clear the question of Shao’s sexuality hasn’t been answered. Whether he’s bisexual, gay, or homoromantic ace, I think the door has at least been left open.

- And while we’re on Shao, I have to say I don’t remember if Part One really delved into his history of abuse. I think the implication was always that his relationship with Annie was toxic and abusive but in the way of a drug kingpin with a favored pet. So while I definitely read it for what it was, it wasn’t confirmed until Part Two. Shao comes as close as he can to admitting that he he’s been raped and brainwashed by Annie and the thread of his story that addresses the wounds he obviously still carries is subtle and powerful and PAINFUL. And the way that Cadillac is folded into that story was really moving, too. The show went from playing their jealousy as the trope of “inadequate son hates the favored adopted son” to really looking at the roots of abuse leading to that situation and to Cadillac’s codependency. And the moment between Shao and Cadillac when Shao lays it all out there and tells Cadillac he knows they both suffered the same abuse was HEARTBREAKING. And shocking in the best way. The fact that this show allowed this kind of vulnerability between two of the more hyper-masculine characters in the show is HUGE. And this is where yes, I’m probably reading too much into it, but I do find it really fascinating that these two men who were sexually abused and are still BEING abused use the f-slur the most liberally. It probably means nothing but it is really fascinating.

- Though I think they did Yolanda dirty (and I get it, it made for great conflict, just really annoying) I DO appreciate Mylene’s loyalty to her girls. And their loyalty to, and belief in, her. Yeah, there’s some sketchy purity stuff involved with Mylene that contributes to this, but it’s also really refreshing to see a story where the most drama the girls had was because one of them wasn’t comfortable being half-naked and grinding on strangers in a club. The rest of the time they love and support each other and that’s awesome.

- The love story between Mylene’s mom and her uncle-dad was SO BEAUTIFUL. I mean it was beautiful in Part One but other than Shao/Zeke and Dizzee/Thor, I think it’s probably my favorite. Just so well-written and well-acted and lovely and painful.

- Still love that The Whites are pretty much globally THE WORST on this show. And love that their proximity to queerness actually indicates how trustworthy they are. Thor? The best. Jackie? Troubled, possibly not to be trusted, but all-in for Mylene. The Australian director guy? Suss until he comes to Jackie’s apartment party. And everyone after that is pretty much trash.

- Honestly some great, shocking moments and zingers in the dialogue. The musical set-pieces were all FABULOUS. The use of music throughout was just top-notch. I was deep in my feelings and loved every minute of it.

- But mostly I LOVE MY PRECIOUS BRONX BABIES AND WANT THEM ALL TO BE SAFE AND HAPPY FOREVER.

. . . I think that’s it. A day has lapsed since I started this tbh so I think some of my thoughts have since drifted to the back of my mind and might yet come back.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Religion of the Faithless Left

Ash Sharp Editor

Puritan Hypocrisy

BLAM goes the gun. OH NO say the victims. WHAT RACE IS THE ATTACKER I HOPE IT’S A WHITE GUY ALSO STOP ISLAMOPHOBIA say the hypocrites.

Puritans are always hypocrites. Read Part I of this series HERE.

Not much more than a decade ago now, the author and political commentator Chris Hedges published a book called American Fascists. It’s an interesting piece, written at the tail end of the turbulent Dubya administration that contended that, within a few years, we would be faced with a Christian Fascist movement in the United States. Based on the popularity of people like Pat Robertson and the politicisation of church-goers by the neocon group that put Reagan in power, Hedges contended that the old right was a threat to American freedom and democracy.

As wonderful a wordsmith as Hedges is, he was, as is sadly so usual for such a smart man, dead wrong. Correctly skewering the old Christian Right for their hypocrisy and often un-Christ-like behaviour is one thing. Predicting the future is quite another. If we are charitable to Hedges few could have seen how, in the decade since Bush, two terms of Obama would enable the hard left to take more social power than could ever have been conceived before.

In the modern age of puritanism, religion is supplanted by Neo-Marxist ideology. Intersectional Theory. Feminism. The root concept which underpins the idea that it is not okay to be White. You can see this everywhere you look, from the television to pop music, to politics and the popular press and sport. The arts of our ancestors speak to us, tell us about their times. Ours will do the same for future generations. Cave paintings teach us that the early humans had a mystical relationship with the animals they hunted and fled from. Renaissance pieces are filled with secrets and satire.

What will our art say about us?

In the realm of faith, the Leftist Puritan happily displays cognitive dissonance during our days of strife. It all boils down to race and religion in the end. If an Islamist mows people down, with a gun or otherwise, the reaction is… nothing. Dire warnings about the dangers of the mythical Islamophobia, perhaps.

Heaven forfend that a white male shoots people. Not only is this an indictment of his race, but he also transforms into an ideologically driven terrorist (Whiteness is political, you know), and a reason to curse out the NRA, and demand gun control. Don’t forget to accuse your enemies of politicising tragedies when it suits your agenda, though.

Shut

If Trump truly cared about the suffering in Syria, he wouldn't have a racist anti-refugee policy. But, hey, bombs distract from scandal!

— Wil 'Kick the Nazis off the tweeters' Wheaton (@wilw) April 7, 2017

UP

I join my fellow Moderate White Person in wishing an Eid of peace, and I also condemn the extremist clan of Trump. http://bit.ly/2leXZRY

— Wil 'Kick the Nazis off the tweeters' Wheaton (@wilw) September 13, 2016

WESLEY

The murdered victims were in a church. If prayers did anything, they'd still be alive, you worthless sack of shit. http://bit.ly/2lm8wKm

— Wil 'Kick the Nazis off the tweeters' Wheaton (@wilw) November 5, 2017

Islam is Peace. Prayers are Worthless. Guns are Bad. I Love Big Brother.

It will stun future generations to hear that we have become such a self-hating society, riddled with such preposterous levels of self-inflicted and undeserved guilt and paranoia.

It wasn’t always like this. In 1979, the seminal comedy group *Monty Python released Life of Brian. The movie revolves around a man mistaken for a messiah. The religious right was apoplectic and it was awesome. And that is coming from a Christian, so save your Jehovahs.

“[Life of Brian] isn’t blasphemous because it doesn’t touch on belief at all. It is heretical because it touches on dogma and the interpretation of belief, rather than belief itself.” ~ Terry Jones

The movie mainly skewered religious hypocrisy and was so controversial at the time that it was banned in several countries and had to rely on George Harrison (of The Beatles) for funding. It remains one of the finest comedies ever produced.

On re-watching the movie recently, I was struck how mild the religious satire really is in this film. In all honesty, I found myself far more interested in the non-theological scenes.

There is a sub-plot to the film which features several Left Wing revolutionary groups all seeking to oust the Romans from Judea. These groups were analogous to hard left British groups in the late 1970s, including the then powerful trade unionists. It is almost as if our timelines are running in opposite directions. As the power of the Church has diminished, to the point where (rightly) no-one would dare attempt to ban a movie for blasphemy, the loony left has arisen, Gojira in Tokyo Harbour.

While the interminable and unending squabbling between the intersections of the left is still laughable today, it cannot be denied that it is the modern day facsimilies of the right-on Reg (John Cleese) and the People’s Front of Judea that are holding the social power. Despite everyone knowing what capitalism has done for us, still, they cry out ‘Oppression!’

Apart from a free market, advances in technology, healthcare, living standards, nearly eliminating child mortality, better food, the internet, a life expectancy of over eighty, university education for all and countless varieties of hot sauce, what has capitalism ever done for us?

Instead, these puritanical crusaders turned their attention on society itself. Internet technology has enabled us to strip monsters like Harvey Weinstein of their veils of secrecy, and therefore, their power. This marvel of communication also allows the Neo-Marxist to conduct witch-hunts and purges at speeds old Joe Stalin could only have dreamed of.

Their zealotry has claimed the scalps of numerous journalists, actors and politicians who, in the main, have all fallen on their swords rather than run the gauntlet. These men may not be nice. These men might, in fact, be criminals- but that has never been a good idea for the mob to decide. **Rupert Myers, late of GQ, is a man who makes my skin crawl. **Not for his alleged behaviour towards women, which seems inept but not illegal, but for his hypocrisy.

Sire! The Virtue Beacon is lit!

To write such a diatribe against the rest of one’s gender, to elevate oneself to the status of Enlightened Nü-Male, and then to be accused thus:

“I was very clear about not being romantically or sexually interested in him, once the subject was raised. I suggested we be mates.

“He said ‘I’ve got enough mates, I’d rather fuck you’ and forced himself on me outside a pub in Fitzrovia.”

Well. I would be a liar if I did not feel a little schadenfreude. I am wrong to do so. A failed and clumsy pass at someone is not a criminal offence, but the puritanical left is treating it like one.

Saints protect you if you live in the United Kingdom, where not only will leftist society pillory you, so will the police. The Sunday Times revealed that the Deputy Prime Minister Damian Green possessed (legal) pornography on his computer. Why is this information pertinent to the public? Are we really so depraved that we must know the masturbatory habits of politicians? If so, why? In any case, the police released it to the press.

The minister has also been pilloried for allegedly touching a woman’s knee. As I predicted when I first published this piece on Medium.com on Nov. 6th, Green has been forced to resign, unable to continue in his career with sucha tarnished public image.

Let’s not ignore that corrupt, incompetent or sleazy politicians must fall. With such incredible levels of vice in politics in our nations, how is it that this non-issue is plastered across the papers?

You can thank Donald J. Trump.

The moralists have been on this crusade for some time, but it appears to have become particularly weaponised by the Left and the MSM since The President’s locker room talk. The scent of blood in the water to a shark is much like the scent of KISS records to a Bible Belt Baptist in 1978 or a whiff of scandal to the press. Egged on by an ideological leitmotif that demands purity at all times from all beings, no man should ever find himself alone with an unmarried woman again.

How we laughed at Vice-President Pence, what a dotard, refusing to sit with a female without his wife present to ensure propriety is maintained. Pence comes to this topic from an entirely different perspective. As a born again, evangelical boomer Catholic we might expect a conservative attitude. But from the sons and daughters of the hippies, the Gen-Xers, the Millennials? I thought this was supposed to be a post-morality, post-faith, post-conservative post-everything age of rampant consumerism and meaningless sex?

No eye contact, a burka, and no sex. Ah, just like back in Gender Studies 101.

Instead, Netflix TV shows are used as examples of a religious theocracy that doesn’t exist. Wow, the asinine Twitterati bleat in unison, this is just like Trump’s America.

It is not. A totalitarian mindset exists in America, for sure. I must also state that the genuinely corrupt who are toppled, the true-life sex-criminals and paedophiles and rapists and money-launderers- spare them no sympathy. They are reaping their own whirlwind, caught up in their pretence at righteousness. The sole irony is that the totalitarians are those who are now purging their movements of male feminist allies for thought crime. Journalists who stood for identity politics are now the victims of the same.

I wonder how long it will be before Dan ‘Everyone is A Literal Nazi’ Arel is cast down from his perch. In the current climate, could it be that his social media stalking of pop has-been Lily Allen transgresses the invisible line of sin?

Dan, stop. That’s creepy.

I knew a guy like this once. A girl turned him down and he cried for days.

No doubt a self proclaimed anarchist like Arel already prays to Black Atheist Trans Jesus for forgiveness for his disgusting white penis. It is not enough today, in 2017, the current year, to merely hate yourself for being a white man. You must also hate the words you say, constantly self-reflect, ensure you keep your eyes down and touch nobody, not even in jest or error.

Such behavioural abnormality is non-PC. Such behaviour demands that you be flayed in public, to lose your livelihood. This is how puritans project their power. Shame is how they maintain control. We have moved beyond expanding the definition of words so that one can be raped by eyesight or by flatulence. We are now in an era where all actions are sinful. There is no escaping the shame. You are born in it, surrounded by it, you are the sin itself. It is, dare I say it, original in nature.

Submission looks like this. A dog, with it’s legs in the air and throat bared.

Considering so many of these leftists proclaim themselves anarchists but act like dictators, I offer my own favoured anarchy.

“Anarchy is personal; it is not a collective possibility. It rests upon the idea of a person acting within a sphere where his existence is not intrusive upon the existence of another human being unless invited to be so. Should a person find that he has uninvitedly trespassed upon the serenity of another, Individual Anarchy points that man toward accepting the responsibility for his own actions while not condemning the failure of others to own up to the things they may have done wrong.” ~ U. Buster

By this perspective, the moral crusade is anathema to anarchists. Even old Antonio Gramsci, one of the founders of Neo-Marxist thought, held it to be a fact that

To tell the truth, to arrive together at the truth, is a communist and revolutionary act.

If we can agree with a long-dead communist that the truth is revolutionary, there may yet be hope for us. We must turn away from this cult of social purity, and the trappings of transcendental shaming. The internet never forgets. We’re all stuck on this rock together, forever.

http://bit.ly/2lm8CBI

0 notes

Link

This piece will be appearing in the next issue of the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly Journal: Comedy Issue, No. 17

To support the Los Angeles Review of Books and receive the next issue, donate to our fund drive today or become a member.

¤

“Laughs exude from all our mouths.” — Hélène Cixous

“Comedy, you broke my heart.” — Lindy West

¤

IN A BIT about sexual violence in his 2010 concert film Hilarious (recorded in 2009), the now-infamous Louis C.K. says: “I’m not condoning rape, obviously — you should never rape anyone. Unless you have a reason, like if you want to fuck somebody and they won’t let you.” I was delighted when I first encountered this joke on Jezebel in July 2012 in a post called “How to Make a Rape Joke.” Lindy West was responding to the social media controversy surrounding American comedian Daniel Tosh, who had recently taunted a female heckler with gang rape. West’s insightful essay later led to a 2013 TV debate with comedian Jim Norton as well as her best-selling memoir, Shrill: Notes from a Loud Woman, where she describes the fallout of becoming one of the United States’s best-known feminist comedy commentators, including her subsequent, painful decision to stop going to comedy shows.

In “How to Make a Rape Joke,” West wondered whether it is ever okay to approach sexual violence with humor. She wrote that she understood and respected those, like the woman who called out Tosh, for whom it wasn’t, categorically. The sexual assault of women poses a special problem for comedy, she reasoned, because it is an expression of structural discrimination against women. That is, unlike misfortunes such as cancer and dead babies known to befall people at random, if you’re a woman, not only do you face a one in three chance of becoming a target of sexual violence, but you will also likely be held at least partly responsible for it. To illustrate the inappropriateness of jokes about this kind of a situation, she drew a comic analogy between patriarchal society and a place where people are regularly mangled by defective threshing machines and then blamed for their own deaths: “If you care […] about humans not getting threshed to death, then wouldn’t you rather just stick with, I don’t know, your new material on barley chaff (hey, learn to drive, barley chaff!)?” Compassion about a culturally loaded form of suffering would seem, automatically and intuitively, to preclude humor about it. Yet West’s own humorous reframing demonstrated what she ultimately decided: that you could be funny about sexual violence if you “DO NOT MAKE RAPE VICTIMS THE BUTT OF THE JOKE.” In particular, Louis C.K.’s rape joke then earned West’s stamp of approval because, in her words:

[It] is making fun of rapists — specifically the absurd and horrific sense of entitlement that accompanies taking over someone else’s body like you’re hungry and it’s a delicious hoagie. The point is, only a fucking psychopath would think like that, and the simplicity of the joke lays that bare.

Though her recent New York Times piece “Why Men Aren’t Funny” makes it clear that West now regards her defense of Louis C.K. as a relic, her sharp distinction between acceptable and unacceptable jokes in “How to Make a Rape Joke” set the standard for mainstream feminist discussions of comedy for a good five years.