#and a fully populated speer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

“We’ll be educating Archie, so we’ll be busy for a while...”

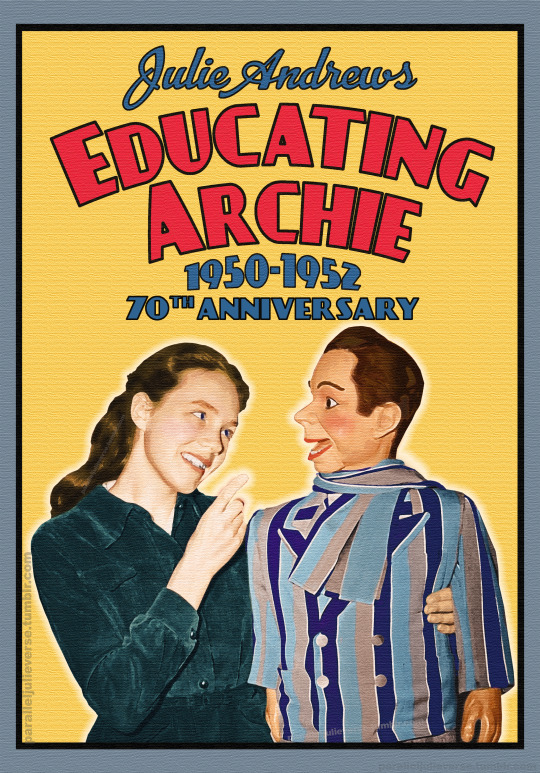

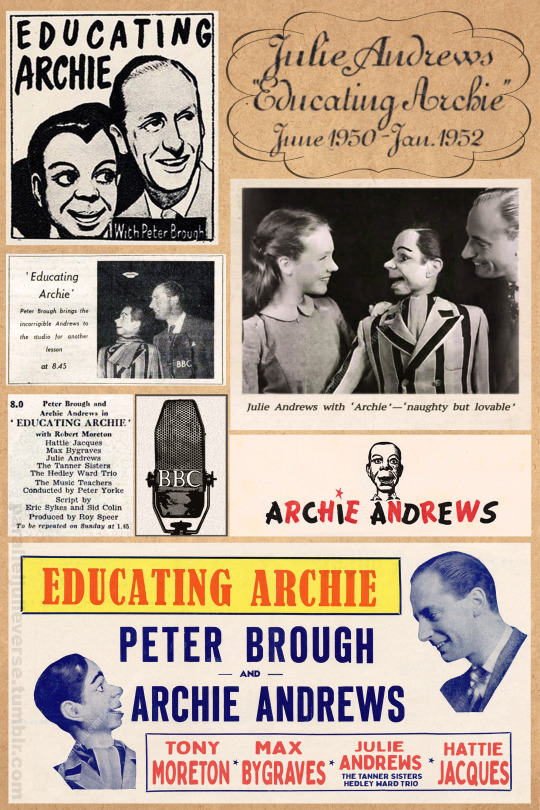

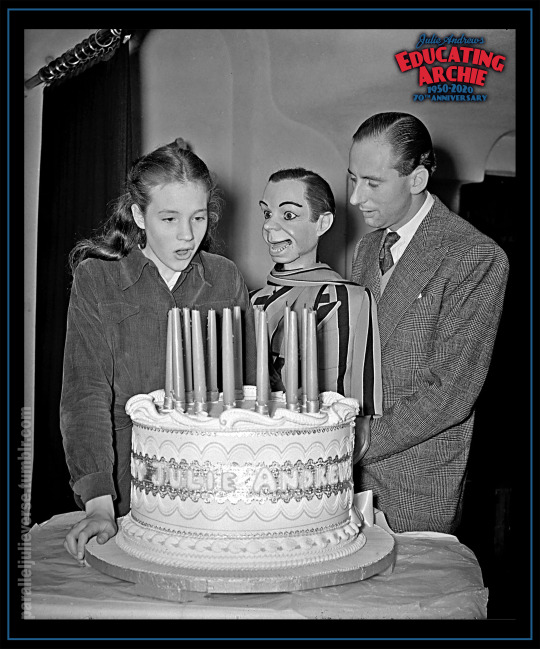

We are a little late with this commemorative post, but last month -- 6 June, to be precise -- marked the 70th anniversary of the debut of Educating Archie (1950-59), the legendary BBC radio series starring ventriloquist Peter Brough and his dummy, Archie Andrews. Fourteen-year-old Julie Andrews was part of the original line-up for the 1950 premiere season of Educating Archie and she would remain with the show for two full seasons till late-1951/early-1952.

It would be difficult to exaggerate the significance of Educating Archie during the ‘Golden Age' of BBC Radio in the 1950s. Across the ten years it was on the air, it grew from a popular series on the Light Programme into a “national institution” (Donovan, 74). At its peak, the series averaged a weekly audience of over 15 million Britons, almost a third of the national population (Elmes, 208). Even the Royals were apparently fans, with Brough and Archie invited to perform several times at Windsor Castle (Brough, 162ff). The show found equal success abroad, notably in Australia, where a special season of the series was recorded in 1957 (Foster and First, 133).

Audiences couldn’t get enough of the smooth-talking Brough and his smart-lipped wooden sidekick, and the show soon spawned a flood of cross-promotional spin-offs and marketing ventures. There were Educating Archie books, comics, records, toys, games, and clothing. An Archie Andrews keyring sold half a million units in six months and the Archie Andrews iced lolly was one of the biggest selling confectionary items of the decade (Dibbs 201). More than a mere radio programme, Educating Archie became a cultural phenomenon that “captured the heart and mood of a nation” (Merriman, 53).

On paper, the extraordinary success of Educating Archie can be hard to fathom. After all, what is the point of a ventriloquist act on the radio where you can’t see the artist’s mouth or, for that matter, the dummy? Ventriloquism is, however, more than just the simple party trick of “voice-throwing”. A good “vent” is at heart a skilled actor who can use his or her voice to turn a wooden doll into a believable character with a distinct personality and dynamic emotional life. It is why many ventriloquists have found equal success as voice actors in animation and advertising (Lawson and Persons, 2004).

Long before Educating Archie, several other ventriloquist acts showed it was possible to make a successful transition to the audio-only medium of radio. Most famous of these was the American Edgar Bergen who, with his dummy Charlie McCarthy, had a top-rating radio show which ran in the US for almost two decades from 1937-1956 (Dunning, 226). Other local British precedents were provided by vents such as Albert Saveen, Douglas Craggs and, a little later, Arthur Worsley, all of whom had been making regular appearances on radio variety programmes for some time (Catling, 81ff; Street, 245).

By his own admission, Peter Brough was not the most technically proficient of ventriloquists. A longstanding joke -- possibly apocryphal but now the stuff of showbiz lore -- runs that he once asked co-star Beryl Reid if she could ever see his lips move. “Only when Archie’s talking,” was her deadpan response (Barfe, 46). But Brough -- described by one critic as “debonair, fresh-faced and pleasantly toothy” (Wilson “Dummy”, 4) -- had an engaging performance style and he cultivated a “charismatic relationship with his doll as the enduring and seductive Archie Andrews” (Catling, 83). Touring the variety circuit throughout the war years, he worked hard to perfect his one-man comedy act with him as the sober straight man and Archie the wise-cracking cut-up.

Inspired by the success of the aforementioned Edgar Bergen -- whose NBC radio shows had been brought over to the UK to entertain US servicemen during the war -- Brough applied to audition his act for the BBC (Brough, 43ff). It clearly worked because the young vent soon found himself performing on several of the national broadcaster’s variety shows. His turn on one of these, Navy Mixture, proved so popular that he secured a regular weekly segment, “Archie Takes the Helm” which ran for forty-six weeks (ibid, 49). While appearing on Navy Mixture, Brough worked alongside a wide range of other variety artists, including, as it happens, a husband and wife performing team by the name of Ted and Barbara Andrews.

Fast forward several years to 1950 and, in response to his surging popularity, Brough was invited by the BBC to mount a fully-fledged radio series built around the mischievous Archie (Brough, 77ff). A semi-sitcom style narrative was devised -- written by Brough’s longtime writing partner, Sid Colin and talented newcomer, Eric Sykes -- in which Archie was cast as “a boy in his middle teens, naughty but lovable, rather too grown up for his years-- especially where the ladies are concerned -- and distinctly cheeky” (Broadcasters, 5). Brough was written in as Archie’s guardian who, sensing the impish lad needed to be “taken strictly in hand before he becomes a juvenile delinquent,” engages the services of a private tutor to “educate Archie” (ibid.). Filling out the weekly tales of comic misadventure was a roster of both regular and one-off characters. In the first season, the Australian comedian, Robert Moreton, was Archie's pompous but slightly bumbling tutor, Max Bygraves played a likeable odd-job man, and the multi-talented Hattie Jacques voiced the part of Agatha Dinglebody, a dotty neighbourhood matron who was keen on the tutor, along with several other comic characters (Brough, 78-81).

In keeping with the variety format popular at the time, it was decided the series would also feature weekly musical interludes. “Our first choice” in this regard, recalls Peter Brough (1955), “was little Julie Andrews”:

“A brief two years before [Julie] had begun her professional career as a frail, pig-tailed, eleven-year-old singing sensation, startling the critics in Vic Oliver’s ‘Starlight Roof’ at the London Hippodrome by her astonishingly mature coloratura voice. Many people of the theatrical world were ready to scoff, declaring the child’s voice was a freak, that it could not last or that such singing night after night would injure her throat. They did not reckon with Julie’s mother, Barbara, and father, Ted: nor with her singing teacher, Madame Stiles-Allen. In their care, the little girl, who had sung ‘for the fun of it’ since she was seven, continued a meteoric career that has few, if any rivals” (81).

As further context for Julie’s casting in Educating Archie, the fourteen-year-old prodigy had already appeared on several earlier BBC broadcasts and was thus well known to network management. In fact, Julie had already worked with the show’s producer, Roy Speers, on his BBC variety show, Starlight Hour in 1948 (Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I).

Julie’s role in Educating Archie was essentially that of the show’s resident singer who would come out and perform a different song each week. In the first volume of her memoirs, Julie recalls:

“If I was lucky, I got a few lines with the dummy; if not, I just sang. Working closely with Mum and [singing teacher] Madame [Stiles-Allen], I learned many new songs and arias, like ‘The Shadow Waltz’ from Dinorah; ‘The Wren’; the waltz songs from Romeo and Juliet and Tom Jones; ‘Invitation to the Dance’; ‘The Blue Danube’; ‘Caro Nome’ from Rigoletto; and ‘Lo, Hear the Gentle Lark’” (Andrews 2008, 126)

Other numbers performed by Julie during her appearances on Educating Archie include: “The Pipes of Pan”, “My Heart and I”, “Count Your Blessings”, “I Heard a Robin”, and “The Song of the Tritsch-Tratsch” (”Song Notes”, 11; Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I). Additional musical interludes were provided by other regulars on the show such as Max Bygraves, the Hedley Ward Trio and the Tanner Sisters.

Alongside her weekly showcase song, Julie’s role was progressively built into a character of sorts as the eponymously named ‘Julie’, a neighbourhood friend of Archie’s. In a later BBC retrospective, Brough recalled that it was actually Julie’s idea to flesh out her part:

“We were thinking of Educating Archie and dreaming up the idea...and we wanted something fresh in the musical spot. We had just heard Julie Andrews with Vic Oliver in Starlight Roof...and we thought, why not Julie with that lovely fresh voice, this youngster with a tremendous range? So we asked her to come and take part in the trial recording and she came up with her mother and her music teacher, Madame Stiles-Allen...and Julie was a tremendous hit, absolutely right from the start. She used to sing those lovely Strauss waltzes...and all those lovely songs and hit the high notes clear as a bell. And then she came to me and said, ‘Look...I’m just doing the song spot, do you think I could just do a line or two with Archie and develop a little talking, a little character work?’ So, I said, ‘I don’t see why not’, So we talked to Eric Sykes and Roy Speer and, suddenly, we started with Julie talking lines back-and-forth with Archie, and Eric developed the character for her of the girl-next-door for Archie, very sweet, quite different from the sophisticated young lady she is today, but a lovely sweet character” (cited in Benson 1985)

As intimated here, an initial trial recording of Educating Archie was commissioned by the BBC, ostensibly to gauge if the format would work or not. This recording was made with the full cast on 15 January 1950 and was sufficiently well received for the broadcaster to green-light a six-episode pilot series to start in June as a fill-in for the popular comedy programme, Take It From Here during that series’ summer hiatus (Pearce, 4). The first episode of Educating Archie was scheduled for Tuesday 6 June in the prime 8:00pm evening slot, with a repeat broadcast the following Sunday afternoon at 1:45pm (Brough, 88ff).

All of the shows for Educating Archie were pre-recorded at the BBC’s Paris Cinema in Lower Regent Street. Typically, each week’s episode would be rehearsed in the afternoon and then performed and recorded later that evening in front of a live audience. Julie’s fee for the show was set at fifteen guineas (£15.15s.0d) for the recording, with an additional seven-and-a-half guineas (£7.17s.6d) per UK broadcast, 3 guineas (£3.3s.0d) for the first five overseas broadcasts, and one-and-a-half guineas for all other broadcasts (£1.11s.6d) (Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I).

The initial six-episodes of Educating Archie proved so popular that the BBC quickly extended the series for another six episodes from 18 July to 22 August (“So Archie,” 5). Of these Julie appeared in four -- 25 July, 1, 8, 14 August -- missing the fist and last episode due to prior performance commitments with Harold Fielding. Subsequently, the show -- and, with it, Julie’s contract -- was extended for a further eight episodes (29 August-17 October), then again for another eight (23 October-18 December). These later extensions were accompanied by a scheduling shift from Tuesday to Monday evening, with the Sunday afternoon repeat broadcast remaining unchanged (Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I). All up, the first season of Educating Archie ran for thirty weeks, five times its original scheduled length. During that time, the show’s audience jumped from an initial 4 million listeners to over 12 million (Dibbs, 200-201). It was also voted the top Variety Show of the year in the annual National Radio and Television Awards, a mere four-and-a-half months after its debut (Brough, 98; Wilson “Archie”, 3).

Given the meteoric success of the show, the cast of Educating Archie found themselves in hot demand. Peter Brough (1955) relates that there was a growing clamour from theatre producers for stage presentations of Educating Archie, including an offer from Val Parnell for a full-scale show at the Prince of Wales in the heart of the West End (101). He demurred, feeling the timing wasn’t yet right and that it was too soon for the show “to sustain a box office attraction in London” -- though he left the door open for future stage shows (102).

One venture Brough did green-light was a novelty recording of Jack and the Beanstalk with select stars of Educating Archie, including Julie. Spread over two sides of a single 78rpm, the recording was a kind of abridged fantasy episode of the show cum potted pantomime with Brough/Archie as Jack, Hattie Jacques as Mother, and Peter Madden as the Giant. Julie comes in at the very end of the tale to close proceedings with a short coloratura showcase, “When We Grow Up” which was written specially for the recording by Gene Crowley. Released by HMV in December 1950, the recording was pitched to the profitable Christmas market and, backed by a substantial marketing campaign, it realised brisk sales (“Jack,” 12). It was also warmly reviewed in the press as “a very well presented and most enjoyable disc” (“Disc,” 3) and “something to which children will listen again and again” (Tredinnick, 628).

In light of its astonishing success, there was little question that Educating Archie would be renewed for another season in 1951. In fact, it occasioned something of a bidding war with Radio Luxembourg, a competitor commercial network, courting Brough with a lucrative deal to bring the show over to them (Brough, 103-4). Out of a sense of professional loyalty to the BBC -- and, no doubt, sweetened by a counter-offer described by the Daily Express as “one of the biggest single programme deals in the history of radio variety in Britain” (cited in Brough, 104) -- Brough re-signed with the national broadcaster for a further three year contract.

For their part, the BBC was keen to get the new season up on the air as early as possible with an April start-date mooted. Brough, however, wanted to give the production team an extended break and, more importantly, secure enough time to develop new material with his writing team. Rising star scriptwriter, Eric Sykes was already overstretched with a competing assignment for Frankie Howerd so a later start for August was eventually confirmed (Brough, 105ff). The Educating Archie crew did, however, re-form for a one-off early preview special in March, Archie Andrew’s Easter Party, which reunited much of the original cast, including Julie (Gander, 6).

The second 1951 season started in earnest in late-July with pre-recordings and rehearsals, followed by the first episode which was broadcast on 3 August. This time round, the programme would air on Friday evenings at 8:45pm with a repeat broadcast two days later on Sunday at 6:00pm. The cast remained more-or-less the same with the exception of Robert Moreton who had, in the interim, secured his own radio show. Replacing him as Archie’s tutor was another up-and-coming comedy talent by the name of Tony Hancock (Brough, 111). It was the start of what would prove a star-making cycle of substitute tutors over the years which would come to include Harry Secombe, Benny Hill, Bruce Forsyth, and Sid James (Gifford 1985, 76). A further cast change would occur midway through Season 2 with the departure of Max Bygraves who left in October to pursue a touring opportunity as support act for Judy Garland in the United States (Brough, 113-14).

The second season of Educating Archie ran for 26 weeks from 3 August 1951 till 25 January 1952. Of these, Julie performed in 18 weekly episodes. She missed two episodes in late September due to other commitments and was absent from later episodes after 14 December due to her starring role in the Christmas panto, Aladdin at the London Casino. She was originally scheduled to return to Educating Archie for the final remaining shows of the season in January and her name appears in newspaper listings for these episodes. However, correspondence on file at the BBC Archives suggests she had to pull out due to ongoing contractual obligations with Aladdin which had extended its run due to popular demand (Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I).

Season 2 would mark the end of Julie’s association with Educating Archie. When the show resumed for Season 3 in September 1952, there would be no resident singer. Instead, the producers adopted “a policy of inviting a different guest artiste each week” (Brough 118). They also pushed the show more fully into the realm of character-based comedy with the inclusion of Beryl Reid who played a more subversive form of juvenile girl with her character of Monica, the unruly schoolgirl (Reid, 60ff). Moreover, by late 1952, Julie was herself “sixteen going on seventeen” and fast moving beyond the sweet little girl-next-door kind of role she had played on the show.

Still, there can be no doubt that the two years Julie spent with Educating Archie provided a major boost to her young career. Broadcast weekly into millions of homes around the nation, the programme afforded Julie a massive regular audience beyond anything she had yet experienced and helped consolidate her growing celebrity as a “household name”. Because Archie only recorded one day a week, Julie was still able to continue a fairly busy schedule of concerts and live performances, often travelling back to London for the broadcast before returning to various venues around the country (Andrews, 127). As a sign of her evolving star status, promotion for many of these appearances billed her as “Julie Andrews, 15 year old star of radio and television” (”Big Welcome,” 7) or even “Julie Andrews the outstanding radio and stage singing star from Educating Archie” (”Stage Attractions,” 4). In fact, Julie made at least two live appearances in this era alongside Brough and other members of the Educating Archie crew with a week at the Belfast Opera House in October 1951 and another week in November at the Gaumont Theatre Southampton (Programme, 1951).

Additionally, the fact that the episodes of Educating Archie were all pre-recorded means that the show provides a rare documentary record of Julie’s childhood performances. To date, several episodes with Julie have been publicly released. These include recordings of her singing “The Blue Danube” from 30 October 1950 and the popular Kathryn Grayson hit, “Love Is Where You Find It” from 19 October 1951. Given recordings of the series were issued to networks around Britain and even sent abroad suggests there must be others in existence and, so, we can only hope that more episodes with Julie will surface in time.

Reflecting on the cultural significance of Educating Archie, Barrie Took observes that, “Over the years [the] programme became a barometer of success; more than any other radio comedy it was the showcase of the emerging top-liner” (104). Indeed, the show’s alumni roll reads like a veritable “who’s who” of post-war British talent: Peter Brough, Eric Sykes, Hattie Jacques, Max Bygraves, Tony Hancock, Alfred Marks, Beryl Reid, Harry Secombe, Bruce Forsyth, Benny Hill, Warren Mitchell, Sid James, Marty Feldman, Dick Emery (Foster and Furst, 128-32). All big talents and even bigger names. However, it is perhaps fitting that, in a show built around a pint-sized dummy, the biggest name of all to come out of Educating Archie -- and, sadly, the only cast-member still with us today -- should be “little Julie Andrews”.

Sources:

Andrews, Julie. Home: A Memoir of My Early Years. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2008.

Baker, Richard A. Old Time Variety: An Illustrated History. Barnsley: Remember When, 2010.

Barfe, Louis. Turned Out Nice Again: The Story of British Light Entertainment. London: Atlantic Books, 2008.

Benson, John (Pres.). “Julie Andrews, A Celebration, Part 2.” Star Sound Special. Luke, Tony (Prod.), radio programme, BBC 2, 7 October 1985.

“Big Welcome for Julie Andrews.” Staines and Ashford News. 17 November 1950: 7.

Broadcasters, The. “Both Sides of the Microphone.” Radio Times. 4 June 1950: 5.

Brough, Peter. Educating Archie. London: Stanely Paul & Co., 1955.

Catling, Brian. “Arthur Worsley and the Uncanny Valley.” Articulate Objects: Voice, Sculpture and Performance. Satz, A. and Wood, J. eds. Bern: Peter Lang, 2009: 81-94.

Dibbs, Martin. Radio Fun and the BBC Variety Department, 1922—67. Chams: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018.

“Disc Dissertation.” Lincolnshire Echo. 11 December 1950: 3.

Donovan, Paul. “A Voice from the Past.” The Sunday Times. 17 December 1995: 74.

Dunning, John. On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Elmes, Simon. Hello Again: Nine Decades of Radio Voices. London: Random House, 2012.

Fisher, John. Funny Way to Be a Hero. London: Frederick Muller, 1973.

Foster, Andy and Furst, Steve. Radio Comedy, 1938-1968: A Guide to 30 Years of Wonderful Wireless. London: Virgin Books, 1996.

Gander, L Marsland. “Radio Topics.” Daily Telegraph. 13 March 1951: 6.

Gifford, Denis. The Golden Age of Radio: An Illustrated Companion. London: Batsford, 1985.

____________. “Obituary: Peter Brough.” The Independent. 7 June 1999: 11.

“Jack and the Beanstalk.” His Masters Voice Record Review. Vol. 8, no. 4, December 1950: 12.

Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I, 1945-61. Papers. BBC Written Archives Centre, Caversham.

Lawson, Tim and Persons, Alissa. The Magic Behind the Voices: A Who's Who of Cartoon Voice Actors. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi Press, 2004.

Merriman, Andy. Hattie: The Authorised Biography of Hattie Jacques. London: Aurum Press, 2008.

Pearce, Emery. “Dummy is Radio Star No. 1.” Daily Herald. 6 April 1950: 4.

Programme for Peter Brough and All-Star Variety at the Belfast Opera House, 22 October 1951, Belfast.

Programme for Peter Brough and All-Star Variety at the Gaumont Theatre Southampton, 12 November 1951, Southampton.

Reid, Beryl. So Much Love: An Autobiography. London: Hutchinson, 1984

“So Archie Stays on.” Daily Mail. 1 July 1950: 5.

“Song Notes.” The Stage. 28 September 1950: 11.

“Stage Attractions: Arcadia.” Lincolnshire Standard. 18 August 1951: 4

Street, Seán. The A to Z of British Radio. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009.

Took, Barry. Laughter in the Air: An Informal History of British Radio Comedy. London: Robson Books, 1976.

Tredinnick, Robert. “Gramophone Notes.” The Tatler and Bystander. 13 December 1950: 628.

Wilson, Cecil. “Dummy Steals the Spotlight.” Daily Mail. 27 May 1950: 4.

____________. “Archie, Petula Soar to the Top.” Daily Mail. 20 October 1950: 3.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2020

#julie andrews#educating archie#peter brough#archie andrews#radio#bbc#british#1950s#ventriloquist#hattie jacques#max bygraves#tony hancock

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Color of COVID: Will Vaccine Trials Reflect America’s Diversity?

When U.S. scientists launch the first large-scale clinical trials for COVID-19 vaccines this summer, Antonio Cisneros wants to make sure people like him are included.

Cisneros, who is 34 and Hispanic, is part of the first wave of an expected 1.5 million volunteers willing to get the shots to help determine whether leading vaccine candidates can thwart the virus that sparked a deadly pandemic.

“If I am asked to participate, I will,” said Cisneros, a Los Angeles cinematographer who has signed up for two large vaccine trial registries. “It seems part of our duty.”

It will take more than duty, however, to ensure that clinical trials to establish vaccine safety and effectiveness actually include representative numbers of African Americans, Latinos and other racial minorities, as well as older people and those with underlying medical conditions, such as kidney disease.

Black and Latino people have been three times as likely as white people to become infected with COVID-19 and twice as likely to die, according to federal data obtained via a lawsuit by The New York Times. Asian Americans appear to account for fewer cases but have higher rates of death. Eight out of 10 COVID deaths reported in the U.S. have been of people ages 65 and older. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns that chronic kidney disease is among the top risk factors for serious infection.

Antonio Cisneros, a Los Angeles cinematographer, signed up for two COVID-19 vaccine trial registries. He is among the first wave of volunteers. “If I am asked to participate, I will,” says Cisneros. “It seems part of our duty.”(Photo by Steven Shea)

Historically, however, those groups have been less likely to be included in clinical trials for disease treatment, despite federal rules requiring minority and elder participation and the ongoing efforts of patient advocates to diversify these crucial medical studies.

In a summer dominated by COVID-19 and protests against racial injustice, there are growing demands that drugmakers and investigators ensure that vaccine trials reflect the entire community.

“If Black people have been the victims of COVID-19, we’re going to be the key to unlocking the mystery of COVID-19,” said the Rev. Anthony Evans, president of the National Black Church Initiative, a coalition of 150,000 African American churches.

Evans and his team met in mid-July with officials from Moderna, the Massachusetts biotech firm that launched the first COVID vaccine trial in the U.S., to discuss a collaboration in which NBCI would supply African American participants. But that was less than two weeks before the start of a phase 3 trial expected to enroll 30,000 people, and Evans said the meeting was his idea.

“It’s not that the industry came to me,” he said. “I went to the industry.”

Blacks make up about 13% of the U.S. population but on average 5% of clinical trial participants, research shows. For Hispanics, trial participation is about 1% on average, though they account for about 18% of the population.

When it comes to trials for drug treatments and vaccines, diversity matters. For reasons not always fully understood, people of different races and ethnicities can respond differently to drugs or therapies, research shows. Immune response wanes with age, so there’s a high-dose flu shot for people 65 and older.

Still, the pressure to produce an effective vaccine quickly during a pandemic could sideline efforts to ensure diversity, said Dr. Kathryn Stephenson, director of the clinical trials unit in the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

“One of the questions that has come up is, What do you do if you’re a site investigator and you have 250 people banging on your door — and they’re all white?” she said.

Do you enroll those people, reasoning that the faster the trial progresses, the faster a vaccine will be available for everyone? Or do you turn away people and slow down the study?

“You’re accelerating development of a vaccine, and if you hit a milestone, what is the meaning of that milestone if you don’t know if it’s very safe or effective in [a given] population? Is that really hitting the milestone for everyone?” she said.

Including people who are elderly or have underlying medical conditions is vital to the science of vaccines and other treatments, even if it’s more difficult to recruit patients otherwise healthy enough to participate, advocates said.

“We have to admit that older adults are the ones who are likely to develop side effects” to treatments and vaccines, said Dr. Sharon Inouye, director of the Aging Brain Center and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “On the other hand, that is the population that will be using it.”

People with kidney disease, which affects 1 in 7 U.S. adults, have been left out of clinical research for decades, said Richard Knight, a transplant recipient and president of the American Association of Kidney Patients. Nearly 70% of more than 400 kidney disease patients the organization surveyed in July said they’d never been asked to join a clinical trial.

Excluding from the vaccine trial such a large population vulnerable to COVID doesn’t make sense, Knight contended. “If you’re trying to manage this from a public health standpoint, you want to make sure you’re inoculating your highest-risk populations,” he said.

New guidance from the federal Food and Drug Administration, which regulates vaccines, “strongly encourages” the inclusion of diverse populations in clinical vaccine development. That includes racial and ethnic minorities, elderly people and those with underlying medical problems, as well as pregnant women.

But the FDA does not require drugmakers and researchers to meet those goals, and will not refuse trial data that doesn’t comply. And while the federal government is rushing billions of dollars to fast-track more than a half-dozen leading candidates for COVID vaccines, the pharmaceutical firms producing them are not required to publicly disclose their demographic goals.

“This is business as usual,” said Marjorie Speers, executive director of Clinical Research Pathways, a nonprofit group in Atlanta that works to increase diversity in research. “It’s very likely these [COVID] trials will not include minorities because there’s not a strong statement to do that.”

The vaccine trials are being coordinated through the COVID-19 Prevention Network, or CoVPN, based at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. It draws on four long-standing federally funded clinical trial networks, including three that target HIV and AIDS.

Those trial networks were chosen in large part because they have rich relationships in Black, Latino and other minority communities, said Stephaun Wallace, director of external relations for CoVPN. The hope is to leverage existing connections based on trust and collaboration.

“Our clinical trial sites are prepped and ready to engage diverse people,” Wallace said.

Wallace acknowledged, however, that attracting a diverse population requires investigators to be flexible and innovative. There can be practical problems. Clinic hours may be limited or transportation may be an issue. Older people may have problems with sight or hearing and require extra help to follow protocols.

Distrust of the medical establishment also can be a barrier. African Americans, for instance, have a well-founded wariness of medical experiments after the infamous Tuskegee Study and the exploitation of Henrietta Lacks. That extends to suspicion about recommended vaccines, said Wallace.

“Part of the consideration for many groups is not wanting to feel like a guinea pig or feel like they’re being experimented on,” he said.

Moderna, which plans to launch its phase 3 trial Monday, said the company is working to ensure participants “are representative of the communities at highest risk for COVID-19 and of our diverse society.”

However, results of the company’s phase 1 trial, released in mid-July, showed that of 45 people included in that safety test, six were Hispanic, two were Black, one was Asian and one was Native American. Forty were white.

Phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials aim to test the best dose and safety of vaccines in small groups of people. Phase 3 trials assess the efficacy of the drug in tens of thousands of people.

Investigators at nearly 90 sites across the U.S. are preparing now to recruit participants for Moderna’s phase 3 trial. Dr. Carlos del Rio, executive associate dean at the Emory University School of Medicine, will seek 750 volunteers at three Atlanta-area sites. Half will receive the vaccine; half, placebo injections.

Del Rio has had marked success recruiting minorities for HIV trials and expects similar results with the vaccine trial. “We’re trying to do our best to get out to the communities that are most at risk,” he said.

Meanwhile, vaccine volunteers like Cisneros just want the advanced trials to start. He signed up for the CoVPN trials. But earlier, he also signed up for 1 Day Sooner, an effort to launch human challenge trials, which aim to speed up vaccine development by deliberately infecting participants with the virus. Such trials can be completed in weeks rather than months but risk exposing volunteers to severe illness or death, and federal officials remain leery.

Cisneros is willing to take that risk to help halt COVID-19, which has killed 143,000 Americans. He said it’s a way to take action at a time when the U.S. government has failed to protect minorities, the elderly and other vulnerable people.

“Government is supposed to help those who can’t protect themselves,” he said. “It appears to me the only thing they want to protect is people with money, people with guns — and not brown people like me.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The Color of COVID: Will Vaccine Trials Reflect America’s Diversity? published first on https://smartdrinkingweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

The Color of COVID: Will Vaccine Trials Reflect America’s Diversity?

When U.S. scientists launch the first large-scale clinical trials for COVID-19 vaccines this summer, Antonio Cisneros wants to make sure people like him are included.

Cisneros, who is 34 and Hispanic, is part of the first wave of an expected 1.5 million volunteers willing to get the shots to help determine whether leading vaccine candidates can thwart the virus that sparked a deadly pandemic.

“If I am asked to participate, I will,” said Cisneros, a Los Angeles cinematographer who has signed up for two large vaccine trial registries. “It seems part of our duty.”

It will take more than duty, however, to ensure that clinical trials to establish vaccine safety and effectiveness actually include representative numbers of African Americans, Latinos and other racial minorities, as well as older people and those with underlying medical conditions, such as kidney disease.

Black and Latino people have been three times as likely as white people to become infected with COVID-19 and twice as likely to die, according to federal data obtained via a lawsuit by The New York Times. Asian Americans appear to account for fewer cases but have higher rates of death. Eight out of 10 COVID deaths reported in the U.S. have been of people ages 65 and older. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns that chronic kidney disease is among the top risk factors for serious infection.

Antonio Cisneros, a Los Angeles cinematographer, signed up for two COVID-19 vaccine trial registries. He is among the first wave of volunteers. “If I am asked to participate, I will,” says Cisneros. “It seems part of our duty.”(Photo by Steven Shea)

Historically, however, those groups have been less likely to be included in clinical trials for disease treatment, despite federal rules requiring minority and elder participation and the ongoing efforts of patient advocates to diversify these crucial medical studies.

In a summer dominated by COVID-19 and protests against racial injustice, there are growing demands that drugmakers and investigators ensure that vaccine trials reflect the entire community.

“If Black people have been the victims of COVID-19, we’re going to be the key to unlocking the mystery of COVID-19,” said the Rev. Anthony Evans, president of the National Black Church Initiative, a coalition of 150,000 African American churches.

Evans and his team met in mid-July with officials from Moderna, the Massachusetts biotech firm that launched the first COVID vaccine trial in the U.S., to discuss a collaboration in which NBCI would supply African American participants. But that was less than two weeks before the start of a phase 3 trial expected to enroll 30,000 people, and Evans said the meeting was his idea.

“It’s not that the industry came to me,” he said. “I went to the industry.”

Blacks make up about 13% of the U.S. population but on average 5% of clinical trial participants, research shows. For Hispanics, trial participation is about 1% on average, though they account for about 18% of the population.

When it comes to trials for drug treatments and vaccines, diversity matters. For reasons not always fully understood, people of different races and ethnicities can respond differently to drugs or therapies, research shows. Immune response wanes with age, so there’s a high-dose flu shot for people 65 and older.

Still, the pressure to produce an effective vaccine quickly during a pandemic could sideline efforts to ensure diversity, said Dr. Kathryn Stephenson, director of the clinical trials unit in the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

“One of the questions that has come up is, What do you do if you’re a site investigator and you have 250 people banging on your door — and they’re all white?” she said.

Do you enroll those people, reasoning that the faster the trial progresses, the faster a vaccine will be available for everyone? Or do you turn away people and slow down the study?

“You’re accelerating development of a vaccine, and if you hit a milestone, what is the meaning of that milestone if you don’t know if it’s very safe or effective in [a given] population? Is that really hitting the milestone for everyone?” she said.

Including people who are elderly or have underlying medical conditions is vital to the science of vaccines and other treatments, even if it’s more difficult to recruit patients otherwise healthy enough to participate, advocates said.

“We have to admit that older adults are the ones who are likely to develop side effects” to treatments and vaccines, said Dr. Sharon Inouye, director of the Aging Brain Center and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “On the other hand, that is the population that will be using it.”

People with kidney disease, which affects 1 in 7 U.S. adults, have been left out of clinical research for decades, said Richard Knight, a transplant recipient and president of the American Association of Kidney Patients. Nearly 70% of more than 400 kidney disease patients the organization surveyed in July said they’d never been asked to join a clinical trial.

Excluding from the vaccine trial such a large population vulnerable to COVID doesn’t make sense, Knight contended. “If you’re trying to manage this from a public health standpoint, you want to make sure you’re inoculating your highest-risk populations,” he said.

New guidance from the federal Food and Drug Administration, which regulates vaccines, “strongly encourages” the inclusion of diverse populations in clinical vaccine development. That includes racial and ethnic minorities, elderly people and those with underlying medical problems, as well as pregnant women.

But the FDA does not require drugmakers and researchers to meet those goals, and will not refuse trial data that doesn’t comply. And while the federal government is rushing billions of dollars to fast-track more than a half-dozen leading candidates for COVID vaccines, the pharmaceutical firms producing them are not required to publicly disclose their demographic goals.

“This is business as usual,” said Marjorie Speers, executive director of Clinical Research Pathways, a nonprofit group in Atlanta that works to increase diversity in research. “It’s very likely these [COVID] trials will not include minorities because there’s not a strong statement to do that.”

The vaccine trials are being coordinated through the COVID-19 Prevention Network, or CoVPN, based at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. It draws on four long-standing federally funded clinical trial networks, including three that target HIV and AIDS.

Those trial networks were chosen in large part because they have rich relationships in Black, Latino and other minority communities, said Stephaun Wallace, director of external relations for CoVPN. The hope is to leverage existing connections based on trust and collaboration.

“Our clinical trial sites are prepped and ready to engage diverse people,” Wallace said.

Wallace acknowledged, however, that attracting a diverse population requires investigators to be flexible and innovative. There can be practical problems. Clinic hours may be limited or transportation may be an issue. Older people may have problems with sight or hearing and require extra help to follow protocols.

Distrust of the medical establishment also can be a barrier. African Americans, for instance, have a well-founded wariness of medical experiments after the infamous Tuskegee Study and the exploitation of Henrietta Lacks. That extends to suspicion about recommended vaccines, said Wallace.

“Part of the consideration for many groups is not wanting to feel like a guinea pig or feel like they’re being experimented on,” he said.

Moderna, which plans to launch its phase 3 trial Monday, said the company is working to ensure participants “are representative of the communities at highest risk for COVID-19 and of our diverse society.”

However, results of the company’s phase 1 trial, released in mid-July, showed that of 45 people included in that safety test, six were Hispanic, two were Black, one was Asian and one was Native American. Forty were white.

Phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials aim to test the best dose and safety of vaccines in small groups of people. Phase 3 trials assess the efficacy of the drug in tens of thousands of people.

Investigators at nearly 90 sites across the U.S. are preparing now to recruit participants for Moderna’s phase 3 trial. Dr. Carlos del Rio, executive associate dean at the Emory University School of Medicine, will seek 750 volunteers at three Atlanta-area sites. Half will receive the vaccine; half, placebo injections.

Del Rio has had marked success recruiting minorities for HIV trials and expects similar results with the vaccine trial. “We’re trying to do our best to get out to the communities that are most at risk,” he said.

Meanwhile, vaccine volunteers like Cisneros just want the advanced trials to start. He signed up for the CoVPN trials. But earlier, he also signed up for 1 Day Sooner, an effort to launch human challenge trials, which aim to speed up vaccine development by deliberately infecting participants with the virus. Such trials can be completed in weeks rather than months but risk exposing volunteers to severe illness or death, and federal officials remain leery.

Cisneros is willing to take that risk to help halt COVID-19, which has killed 143,000 Americans. He said it’s a way to take action at a time when the U.S. government has failed to protect minorities, the elderly and other vulnerable people.

“Government is supposed to help those who can’t protect themselves,” he said. “It appears to me the only thing they want to protect is people with money, people with guns — and not brown people like me.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The Color of COVID: Will Vaccine Trials Reflect America’s Diversity? published first on https://nootropicspowdersupplier.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

The Color of COVID: Will Vaccine Trials Reflect America’s Diversity?

When U.S. scientists launch the first large-scale clinical trials for COVID-19 vaccines this summer, Antonio Cisneros wants to make sure people like him are included.

Cisneros, who is 34 and Hispanic, is part of the first wave of an expected 1.5 million volunteers willing to get the shots to help determine whether leading vaccine candidates can thwart the virus that sparked a deadly pandemic.

“If I am asked to participate, I will,” said Cisneros, a Los Angeles cinematographer who has signed up for two large vaccine trial registries. “It seems part of our duty.”

It will take more than duty, however, to ensure that clinical trials to establish vaccine safety and effectiveness actually include representative numbers of African Americans, Latinos and other racial minorities, as well as older people and those with underlying medical conditions, such as kidney disease.

Black and Latino people have been three times as likely as white people to become infected with COVID-19 and twice as likely to die, according to federal data obtained via a lawsuit by The New York Times. Asian Americans appear to account for fewer cases but have higher rates of death. Eight out of 10 COVID deaths reported in the U.S. have been of people ages 65 and older. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns that chronic kidney disease is among the top risk factors for serious infection.

Antonio Cisneros, a Los Angeles cinematographer, signed up for two COVID-19 vaccine trial registries. He is among the first wave of volunteers. “If I am asked to participate, I will,” says Cisneros. “It seems part of our duty.”(Photo by Steven Shea)

Historically, however, those groups have been less likely to be included in clinical trials for disease treatment, despite federal rules requiring minority and elder participation and the ongoing efforts of patient advocates to diversify these crucial medical studies.

In a summer dominated by COVID-19 and protests against racial injustice, there are growing demands that drugmakers and investigators ensure that vaccine trials reflect the entire community.

“If Black people have been the victims of COVID-19, we’re going to be the key to unlocking the mystery of COVID-19,” said the Rev. Anthony Evans, president of the National Black Church Initiative, a coalition of 150,000 African American churches.

Evans and his team met in mid-July with officials from Moderna, the Massachusetts biotech firm that launched the first COVID vaccine trial in the U.S., to discuss a collaboration in which NBCI would supply African American participants. But that was less than two weeks before the start of a phase 3 trial expected to enroll 30,000 people, and Evans said the meeting was his idea.

“It’s not that the industry came to me,” he said. “I went to the industry.”

Blacks make up about 13% of the U.S. population but on average 5% of clinical trial participants, research shows. For Hispanics, trial participation is about 1% on average, though they account for about 18% of the population.

When it comes to trials for drug treatments and vaccines, diversity matters. For reasons not always fully understood, people of different races and ethnicities can respond differently to drugs or therapies, research shows. Immune response wanes with age, so there’s a high-dose flu shot for people 65 and older.

Still, the pressure to produce an effective vaccine quickly during a pandemic could sideline efforts to ensure diversity, said Dr. Kathryn Stephenson, director of the clinical trials unit in the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

“One of the questions that has come up is, What do you do if you’re a site investigator and you have 250 people banging on your door — and they’re all white?” she said.

Do you enroll those people, reasoning that the faster the trial progresses, the faster a vaccine will be available for everyone? Or do you turn away people and slow down the study?

“You’re accelerating development of a vaccine, and if you hit a milestone, what is the meaning of that milestone if you don’t know if it’s very safe or effective in [a given] population? Is that really hitting the milestone for everyone?” she said.

Including people who are elderly or have underlying medical conditions is vital to the science of vaccines and other treatments, even if it’s more difficult to recruit patients otherwise healthy enough to participate, advocates said.

“We have to admit that older adults are the ones who are likely to develop side effects” to treatments and vaccines, said Dr. Sharon Inouye, director of the Aging Brain Center and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “On the other hand, that is the population that will be using it.”

People with kidney disease, which affects 1 in 7 U.S. adults, have been left out of clinical research for decades, said Richard Knight, a transplant recipient and president of the American Association of Kidney Patients. Nearly 70% of more than 400 kidney disease patients the organization surveyed in July said they’d never been asked to join a clinical trial.

Excluding from the vaccine trial such a large population vulnerable to COVID doesn’t make sense, Knight contended. “If you’re trying to manage this from a public health standpoint, you want to make sure you’re inoculating your highest-risk populations,” he said.

New guidance from the federal Food and Drug Administration, which regulates vaccines, “strongly encourages” the inclusion of diverse populations in clinical vaccine development. That includes racial and ethnic minorities, elderly people and those with underlying medical problems, as well as pregnant women.

But the FDA does not require drugmakers and researchers to meet those goals, and will not refuse trial data that doesn’t comply. And while the federal government is rushing billions of dollars to fast-track more than a half-dozen leading candidates for COVID vaccines, the pharmaceutical firms producing them are not required to publicly disclose their demographic goals.

“This is business as usual,” said Marjorie Speers, executive director of Clinical Research Pathways, a nonprofit group in Atlanta that works to increase diversity in research. “It’s very likely these [COVID] trials will not include minorities because there’s not a strong statement to do that.”

The vaccine trials are being coordinated through the COVID-19 Prevention Network, or CoVPN, based at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. It draws on four long-standing federally funded clinical trial networks, including three that target HIV and AIDS.

Those trial networks were chosen in large part because they have rich relationships in Black, Latino and other minority communities, said Stephaun Wallace, director of external relations for CoVPN. The hope is to leverage existing connections based on trust and collaboration.

“Our clinical trial sites are prepped and ready to engage diverse people,” Wallace said.

Wallace acknowledged, however, that attracting a diverse population requires investigators to be flexible and innovative. There can be practical problems. Clinic hours may be limited or transportation may be an issue. Older people may have problems with sight or hearing and require extra help to follow protocols.

Distrust of the medical establishment also can be a barrier. African Americans, for instance, have a well-founded wariness of medical experiments after the infamous Tuskegee Study and the exploitation of Henrietta Lacks. That extends to suspicion about recommended vaccines, said Wallace.

“Part of the consideration for many groups is not wanting to feel like a guinea pig or feel like they’re being experimented on,” he said.

Moderna, which plans to launch its phase 3 trial Monday, said the company is working to ensure participants “are representative of the communities at highest risk for COVID-19 and of our diverse society.”

However, results of the company’s phase 1 trial, released in mid-July, showed that of 45 people included in that safety test, six were Hispanic, two were Black, one was Asian and one was Native American. Forty were white.

Phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials aim to test the best dose and safety of vaccines in small groups of people. Phase 3 trials assess the efficacy of the drug in tens of thousands of people.

Investigators at nearly 90 sites across the U.S. are preparing now to recruit participants for Moderna’s phase 3 trial. Dr. Carlos del Rio, executive associate dean at the Emory University School of Medicine, will seek 750 volunteers at three Atlanta-area sites. Half will receive the vaccine; half, placebo injections.

Del Rio has had marked success recruiting minorities for HIV trials and expects similar results with the vaccine trial. “We’re trying to do our best to get out to the communities that are most at risk,” he said.

Meanwhile, vaccine volunteers like Cisneros just want the advanced trials to start. He signed up for the CoVPN trials. But earlier, he also signed up for 1 Day Sooner, an effort to launch human challenge trials, which aim to speed up vaccine development by deliberately infecting participants with the virus. Such trials can be completed in weeks rather than months but risk exposing volunteers to severe illness or death, and federal officials remain leery.

Cisneros is willing to take that risk to help halt COVID-19, which has killed 143,000 Americans. He said it’s a way to take action at a time when the U.S. government has failed to protect minorities, the elderly and other vulnerable people.

“Government is supposed to help those who can’t protect themselves,” he said. “It appears to me the only thing they want to protect is people with money, people with guns — and not brown people like me.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

from Updates By Dina https://khn.org/news/the-color-of-covid-will-vaccine-trials-reflect-americas-diversity/

0 notes

Text

For Small, Private Liberal Arts Colleges, What’s the Drive to Go Online?

When financials are steady and a college doesn’t have a desire to expand its reach beyond a physical campus, is online learning necessary—or even relevant?

That was a question posed last week by Janet Russell, director of academic technology for Carleton College, at a session at the Online Learning Consortium’s Innovate conference.

“We are investigating online learning, but it still makes us a little bit nervous,” Russell said to a group of about 30 academic-innovation officials. Many who were in the room work at small liberal arts colleges that are grappling with similar questions around whether or not to pursue online learning—and, if so, how to get campus buy-in.

Located in Minnesota, Carleton College serves about 2,000 students, the majority of which are white and hail from the Midwest and New England. “We are trying to do what many institutions are trying to do, get a more-diverse student population,” said Russell. Digital learning is one way Russell is interested in serving a more inclusive group of students.

So far, the school has only offered one online course, a summer bridge program called CUBE (Carleton Undergraduate Bridge Experience) focusing on quantitative skills. CUBE was met with positive feedback, Russell said, and received permission to run again this past summer in 2017. But the course is “a significant departure from college policies and practices, including having no summer courses and no online courses,” she said.

Now the college is deciding what happens next to CUBE. But despite some success with the online learning experiment, faculty and administration at Carleton are resistant to expand the online presence of the small, private liberal arts school.

Part of that pushback has been due to a perceived lack of necessity. At Thursday’s session, Russell shred that Carleton College is relatively “healthy in terms of its finances,” compared with many academic institutions struggling with decreased funding. As Russell put it: “We would be retired or dead before we felt the pressure that other schools are feeling.” Starting an online program in order to drive revenue just doesn’t resonate.

Another popular narrative from digital learning advocates—that offering online courses can allow an institution to reach and educate more students than before—hasn’t been a very successful argument, either, Russell said. Many faculty at her institution believe strongly in the intimate nature of a small liberal arts college, and tout its ability to offer a uniquely “high-touch” and in-person learning experience. “We are so nervous about using the word ‘online learning,’” she said. “Could this tarnish our brand?”

Russell struggles with these issues. Not because she disagrees, but because she understands well where wary faculty and staff are coming from—and she shares some of their concerns. At the same time, she worries that the campus may hold students back by not allowing them avenues to explore online learning in an increasingly digital world. “There are things our students and faculty could be missing out on by not dipping their toes into this world,” Russell said.

Ask Me Anything

The session on Thursday turned into somewhat of an advice group for the academic officials present, who were seated in a circle and offered Russell insight about their own anxieties and approaches to digital learning.

Eric Hagan, director of distance education and instructional technology at DeSales University, in Pennsylvania, shared how his university previously balked at the notion of online learning. “The original mindset was ‘parents don’t send their kids to live in the dorms and work on their computers.”

Faculty at DeSales began to change their opinions, however, after noticing an increase in the number of fully-online and blended graduate programs, Hagan said. And they wanted to give students an opportunity to experience an online course in preparation for that.

Today, undergraduate students at DeSales have the opportunity to take two online courses. There have been challenges getting those courses set up, “but we thought we were doing students a disservice by not giving them opportunities online,” Hagan said.

Others in the group said that their campus warmed up to offering online courses after realizing that students were turning to other institutions for distance courses anyway.

“We were losing our summer school to larger universities” like Southern New Hampshire University, said Kim Round, director of instructional technology at Saint Anselm College, in New Hampshire. Some faculty at the college were interested in teaching online over the summer to make extra money, so Saint Anselm piloted a digital summer course, and it caught on quickly. This year will mark the fourth year of Saint Anselm’s online summer courses, Round said, and now the college is working on an online winter session as well.

Others shared similar stories. One college official said it was “astonishing” to find out how many transfer credits the school accepted from online programs—and yet none were offered at their own college. Rather than revenue loss, the main worry at her college was whether or not students were receiving an education on par with what they could receive on campus.

“We don’t have control of the quality, and we don't’ know the syllabus [for external online courses],” she said. “If we want quality, why don’t we make online courses ourselves.”

Since adding the online courses, the official claimed that the school’s registrar has noticed less online transfer credits from outside institutions.

Russell was also familiar with the narrative. At a previous institution where she worked, she said, administration began offering online courses after becoming aware that students were taking online courses in the summer through other campuses for cheaper and more flexible options. It was part quality control and part revenue driver that ultimately swayed campus officials to try a program of their own.

Carolyn Speer, at Wichita State University, suggested gauging faculty to see if there is an interest in doing research about online learning, and grounding programs in that. “There is tension around the real and online world, and we are at a point of transition and that is an interesting place for research,” she said. “We aren’t getting less online as a culture, so that’s a potential area for research.”

The idea might work. “Our faculty stay active as researchers and publishing and students are immersed in research off the bat,” Russell said. “I think research is an interesting possibility.”

For Small, Private Liberal Arts Colleges, What’s the Drive to Go Online? published first on https://medium.com/@GetNewDLBusiness

0 notes