#also I learned to speak Spanish from South American telenovelas

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

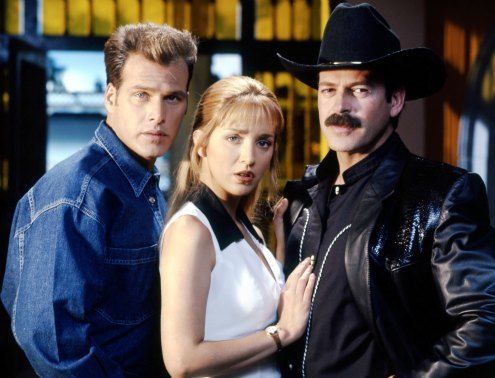

First post. Of course, a Queen. A rebel, poised, genuine and sensitive one. And from the South. ‘Queen of the South’ is a 4-season American crime drama which premiered in the USA in 2016. It is an adaptation from a Spanish-speaking telenovela, ‘La Reina del Sur’, itself an adaptation from a novel by Arturo Pérez-Reverte published in 2002. The American version takes you into the depths of the transborder drug cartel between Mexico (and other Latin-American countries) and the USA as the story follows the rise of Teresa Mendoza, from being a girlfriend to heading the biggest cartel in Mexico.

While having its soapy pitfalls (don’t be discouraged by the trailer, the soapiness is rather sprinkled and makes the show all the more addictive and endearing), the series is rich in sociological and feminist insights, the latter being quite a prowess for a show directed by a man, on the basis of a novel written by another man. There is something very powerful in seeing the various ways in which female bodies are used, damaged and instrumentalised commodities both by and for men and by women themselves. In ‘Queen of the South’, one learns (or remembers) that while patriarchy is unquestionable, it is amenable to some frustratring adjustments for the women who also want to lead. This means for the she-wolf, as always, outsmarting and outpowering the male dogs. You need ‘cojones’ to do that and both Teresa Mendoza, and her she-mentor, the darkly superb Camila Vargas, have, if painfully, acquired/developed plenty of them.

Besides the (pessimistic) feminist take, the show is a must-watch for two additional reasons. First, it depicts drug business as it is, that is as a business before all. Success is not only measured in how physically violent and ruthless one can be with one’s enemies, but also and perhaps most of all with how intelligent one can be business-wise (here, I’m talking figures, product and logistics). Amazon could be the most successful drug cartel ever if the law had criminalized books and the like. The show therefore demonstrates how random the war on drugs’ morality politics are; at the end of the day, it all boils down to who makes the law, who knows the law, and which side you are on, and for how long (and how much cash you have to chose said side).

That being said, it is not always about money. The show is an unexpectedly rather subtle lab of human emotions, and in particular the complexity of long lasting romantic love (and lust). Two relationships (if not three - depending on how one counts but I won’t say more here for fear of breaching the fundamental no-spoiler rule) are at the heart of the plot, illustrating how ethereal yet real love is. I especially commend Peter Gadiot’s excellent acting in that regards, in addition to Alice Braga’s performance as this rare wounded and raw female s-hero who explores her own limits and conscience while answering the deeper calling of her soul for self-actualization. All of us are queens. It just takes (a lot of) courage to become who we are*.

––––

*Silvia Brinton Perera, ‘Descent to the Goddess: A Way of Initiation for Women’ (1981)

––––

WATCH IF YOU...

crave action, thriller vibes, complicated storyline, u-turns

want to see Mexico through money not poverty

appreciate crazy (and ambitious) characters

are looking for a role-model, inspiration and some soul healing

dream of true love and want to see what marriage is really about

need fashion inspiration for sexy corporate female attire

You’re welcome.

––––

Currently available on Netflix.

#queenofthesouth#queen#south#series#crime drama#queen of the south#review#shadesofshallow#shades of shallow#movie critic#netflix#feminist

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black

Pollyanna Rodrigues De La Rosa, who only recently began identifying as Afro-Latina (Photo: Roberto Caruso)

Pollyanna Rodrigues De La Rosa sat in the back of a cab, on her way to her favourite Toronto Latin music club, El Rancho. To get herself in the mood for a Saturday night of salsa, bachata and reggaeton, she asked the driver for the auxiliary cord to play “Eres Mia” by Romeo Santos from her phone. The music filled the cab and she sang along, the lyrics flowing smoothly off her tongue in Spanish, the language she speaks at home with her family. The driver raised his voice over the music and asked Rodrigues De La Rosa about her background—but her answer wasn’t what he was expecting.

“I thought you were Black!” he said. Rodrigues De La Rosa, who is part Cuban and part Panamanian, is used to this type of reaction. She stands at just over five feet tall, with big, long, black curly hair. Her dark skin matches her brown eyes, and if you saw her on the street you’d probably have no doubts about her racial identity, either.

But what the cab driver didn’t understand was that while she is indeed Black, she is also Latina. To be fair, Rodrigues De La Rosa didn’t always understand the nuances of her racial identity, either. “For the longest time, I actually didn’t know I was Black,” she says. That’s because, growing up, her family considered themselves Latino.

Though they shared the same skin tone and hair texture, her family never talked about their African heritage—in fact, they preferred to pretend it didn’t exist. Rodrigues De La Rosa’s mother even pressed her about her romantic choices, questioning why she dated Black men instead of white men. And the anti-Black racism was present in her extended family, too. When she visited Cuba in 2015, many of her family members would ask her to straighten her hair for a “better” look.

Between her family’s Latino identity and the anti-Black rhetoric she internalized, Rodrigues De La Rosa questioned whether or not she identified as Black.

Then, in 2015, she discovered a term on social media that she truly felt described her: Afro-Latina. The broad definition is simple—someone who identifies as Afro-Latina, Afro-Latino or the more inclusive and gender-neutral Afro-Latinx is Black and from Latin America. But the term’s meaning is much more political.

In these communities, which have a deep history of anti-Black racism, Afro-Latinx refers to “someone [from the Latino community] who reclaims their Africanness and Blackness, which for so many years was erased,” explains Columbian-Canadian academic Andrea Vasquez Jimenez, the co-director of the Latinx, Afro-Latin-America, Abya Yala Education Network (LAEN). “Utilizing terms such as Hispanic erases our Blackness.”

While Rodrigues De La Rosa may have felt like she stood out among her peers, she is actually part of a large cultural community. A quarter of the Hispanic population in the U.S. identifies as Afro-Latino according to a 2014 study. (Similar data is not available in Canada in part because though the census includes Black and Latin American as visible minority categories, there is no category combining the two identities. Respondents can write in their own classification, or mark all the categories that apply, but the data is counted towards the Black and Latin American categories separately.)

“I get looked at all the time when I start speaking Spanish. It’s still a culture shock, especially to old farts. I quickly let them know that there are Black people in [Cuba and Panama],” says Rodrigues De La Rosa, adding that people often seem to think that it’s impossible to be both Black and a Spanish-speaking Latina.

“When I heard the term Afro-Latina, as sad as this is going to sound, it was the first time I thought I was considered Black,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa. “I loved it.”

Unlearning anti-Black racism as an Afro-Latina

People like Rodrigues De La Rosa are why Jimenez started LAEN. She made sure the organization was a space for Afro-Latinx people to not only have a voice, but learn about their heritage.

“Blackness is global. An extremely high percentage of [people from Latin America] have African ancestry. The identities of Blackness, Africanness and being Latinx are not mutually exclusive,” says Jimenez.

The African diaspora originated with the transatlantic slave trade, when European colonizers dispersed millions of people from Africa to North America, South America and the Caribbean. And regardless of where slaves were taken, sexual violence was common. “This is the most f-cked up part, I don’t know if my Spanish ancestor loved my great-great-great-grandma or raped her,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa.

The intersectionality of Afro-Latinx people can get even more complex, especially for people like CityNews reporter Ginella Massa, who wears a hijab and is from Panama.

“Often, in the realm of my work, my Muslim identity is discussed; my ethnicity or my heritage are rarely ever mentioned,” says Massa. When she made headlines in 2016 for being the first hijabi news anchor, the coverage described her as a Muslim Canadian, but the Afro-Latinx aspect of her identity took a back seat.

CityNews reporter Ginella Massa

Even within Canadian Afro-Latinx communities, positive discussions about embracing all aspects of this intersectional identity are rare.

“Because of anti-Black racism, many folks don’t necessarily speak nor highlight our Blackness within families,” says Jimenez.

That’s especially true among older generations of Afro-Latinx people, who have internalized centuries of institutionalized anti-Black racism. Massa says her family’s Blackness was rarely discussed at home. Her family only focused on their Latin heritage.

“My grandmother, I can say this certainty, would never identify as Black,” says Massa. “I’m not sure where she got this from because to look at her, you would say she is a Black woman. But there is this obsession with light skin and desire to distance ourselves from Blackness.”

For Rodrigues De La Rosa, learning the term Afro-Latina was the catalyst that allowed her to understand her who she really was. She was tired of people constantly denying her parts of her heritage—but in embracing this term, she also had to go through a process of unlearning the anti-Black racism rooted in her community.

As she learned more, Rodrigues De La Rosa also tried teaching her family about their Afro-Latinx history. But it was challenging, especially since her mother, who grew up in Cuba, was ridiculed by other Cubans for her darker skin and tightly coiled hair.

“I’ve had to teach my mother to love herself more,” she says.

Amara La Negra and Afro-Latina celebs stepping into the spotlight

Celebrities such as Jennifer Lopez, Gina Rodriguez, and Camila Cabello are readily identified as representations of the Latinx community in Hollywood—yet celebs like Zoe Saldana, Orange is the New Black‘s Dascha Polanco and Cardi B are often denied their intersectional identity and instead solely seen as Black.

Earlier this year, reality TV star and singer Amara La Negra, whose parents are from the Dominican Republic, reignited the conversation about Afro-Latinx identity on Love and Hip Hop Miami. In the debut episode, La Negra and producer Young Hollywood were discussing ideas about how she should change her image to better promote her music. La Negra insisted her look represented her Afro-Latina heritage. In response, Hollywood proceeded to question her identity by asking, “Hold on! Afro-Latina? Elaborate, are you African or is that just because you have an afro?”

Reducing an identity to a hair type exemplifies why the Afro-Latinx community struggles with their identity. What Hollywood said demonstrated the common misperception that someone can only a singular racial or cultural identity, which for people like La Negra and Rodrigues De La Rosa is not the case. Immediately after the conversation aired, social media feeds were filled with discussions about what it meant to be Afro-Latinx.

“It’s annoying the fact I feel I always have to defend myself. Defend my race, defend my looks, defend my fro… so if I want to wear it a certain type of way that shouldn’t affect who I am as a person or my music,” La Negra said at the reunion episode.

youtube

The type of representation La Negra is bringing for Afro-Latinx women was totally absent from Rodrigues De La Rosa’s childhood. Growing up, she remembers watching telenovelas on TLN. In all the Spanish-language dramas she watched as a child, she doesn’t remember seeing a single Black actor. Celebs like La Negra are changing that.

“What Amara’s trying to do is, she trying to show that’s there are all types of Latino women, she’s showing the darkest shade,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa.

What’s in a name?

With her newfound sense of identity, Rodrigues De La Rosa is now confident in herself to identify as both Black and Latina—and sets people straight when they question her background.

“Now when I say a sentence in Spanish and people be like ‘Oh my God you speak Spanish? I thought you were Black!’ I don’t find it surprising, I find it ignorant. I choose to enlighten them,” she says.

Her struggle with identity has become less about unlearning her internalized anti-Black racism, and more about educating others every time they question her ethnicity or race. Rodrigues De La Rosa will probably always face questions from people who don’t understand intersectional identities. But that doesn’t stop her from letting them know she exists, and so does the Afro-Latinx community.

Related:

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Ellen Asking Constance Wu “Where Are You From?” Could a DNA Test *Really* Help Me Figure Out My Biracial Identity? Anyone Can Participate in Caribana, and Maybe That’s a Problem

The post For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black appeared first on Flare.

For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black published first on https://wholesalescarvescity.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Lesson 15, Task 2: What has influenced me?

Culture is the language, beliefs, values, norms, behaviours, and material objects that are passed on to future generations of society; while material culture, specifically consists of items within a culture that you can taste, touch, and feel. In a generation infused by mass and social media and at the height of globalization, it’s not hard to understand why a person would be influenced by cultures from around the world. Especially, in the form of material culture as it seems to be the most accessible and appealing to our sensory overstimulated society. It is well known that through processes like socialization our own personal cultures shape and influence us as people. But how often do we consider the impact other cultures around us have, particularly in a country like Canada that defines itself as a cultural mosaic and which in 1988 passed the Canadian Multicultural Act; the first national multiculturalism law in the world? I will be discussing just that in this essay and looking at how cultural aspects such as entertainment, fashion, food, architecture, and leisure activities outside of my own culture influence me.

Entertainment

Whether it's by watching Senegalese movies, listening to Balkan music, playing Japanese video games, gazing at Incan sculptures, or reading Soviet novels and multicultural Sufi poetry; entertainment makes a large part of the “foreign” cultures I consume thanks to the extent of mass and social media. Given my own diverse ethnic and cultural background, I have always been interested in different cultures. One of the most influential sources of my interest came in the form of Mexican and Hispanophone-South American telenovelas. Given that my parents come from Cuba and Brazil, respectfully, to someone looking from an outsider prospective it may be confusing how i.e. Mexican, Peruvian, or Argentinean cultures are that different from mine. However, Latin America is neither a cultural nor a racial monolith, and despite countries like Cuba and Mexico speaking the same language on a national level, they are as different from each other as Canada and Jamaica. Although, both Mexico and Cuba were colonized by the same European colonizers, the Spaniards; their colonial and post-colonial histories evolved uniquely (Collier, Simon, Thomas Skidmore, Harold Blakemore, 1992, pg. 25). Watching Mexican telenovelas as a child introduced me to these differences, especially on a racial and cultural level. In Cuba the majority of the population descends from Europe, Africa, and to a lesser extend China; thus most Cubans are either white, black, black-white biracials (most often multigenerational), or Asian (McAuslan, 2010, pg. 523). Cuba and Mexico, as the rest of the Americas were first both inhabited by Native Americans before the Spaniards came. However, in Cuba diseases and slavery of the Indigenous population almost entirely wiped them out in the first couple decades of the Spaniards arrival (McAuslan, 2010, pg. 408). Mexico on the other hand had one of the largest Native American populations in the entire Americas, and to this day they and their descendants still make a large part of Mexico’s demographics (Clarke, 2018, pg. 22-24). Cuba and Mexico both share a unique history in that the Spaniards, as the French and Portuguese, were more open to mixing with the non-white populations in their colonies, and both countries have large mixed-race populations. Nevertheless, unlike in Mexico where the mixture was largely between Europeans and Native Americans, in Cuba it was largely between Europeans and Africans who were brought to the island as slaves (Clarke, 2018, 22-24; see also Collier et al., 1992; McAuslan, 2010, pg. 408). Also, because of racist policies that encouraged post-colonial Spanish and other European immigrants to the country, Cuba’s white population was much larger than that of Mexico, where the white population is largely concentrated in the upper-class (McAuslan, 2010, pg. 409-413). Cuba, however, gone through a communist revolution largely over-threw and exiled the upper- and middle-class white population, and so growing up in the country I was used to being around poor white, black, Asian, and mixed people. This was unlike what I saw in Mexican telenovelas, whereas the main cast was largely white, often portraying the upper-class, many of the minor characters and extras would be people of visible Native ancestry (Moreno, 2017, March 13). At first it influenced my curiosity, as I was used to seeing white people speaking Spanish, but I was not used to seeing people with such prominent Indigenous American features speaking the language. However, later on I continued to see a trend: the maids, butlers, and poorest characters in these telenovelas would often be the ones who looked to be entirely Native in ancestry. Watching Venezuelan telenovelas I started to see this pattern too, however unlike Mexico, with black characters playing the poorest and least significant roles, and once again white people and predominately white mixed-race people playing the leads and recurring characters, typically those in the middle and upper class. Contemplating on this led me to have a deeper interest in both sociology and history. It had a massive impact on me, because I began to see the patterns in my own culture’s media. This is especially true in Brazilian tv which follows a similar pattern, and where white Brazilians make up the majority of the cast and most important characters, while black Brazilians play less significant and often negatively stereotyped roles. It pushed me to learn about the colonial history of Latin America and how the Spaniards, Portuguese, and French all created caste systems which placed European/white descendants at the top of the pyramid, mixed people in the middle, and Black & Indigenous people at the bottom. (Collier et al., 1992, pg. 22). It taught me that in much of Latin America, things had changed very little since the colonial era and that socio-economic status was heavily influenced by race (Collier et al., 1992, pg. 23-26). This is the antithesis of what many Latin American countries claim, describing their nations as multiracial and multicultural paradises, absent of the racism found in the United States (Collier et al., 1992, pg. 34). Although these polarizations were always present in Brazilian and even Cuban television shows, the larger amount of white and black people in Cuba and Brazil overall interacting positively daily, and the slightly large presence of non-white people in the media of both of these countries, had always given me the impression that what I was taught about racial harmony was true. It was not until seeing these striking racial/social contrasts in Mexican telenovelas that I began to look into the problems of my own culture and beginning my journey into sociology.

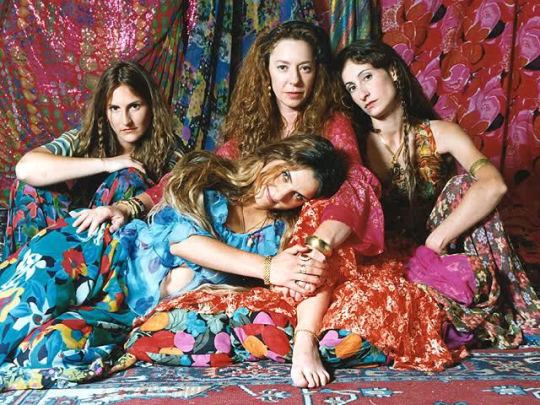

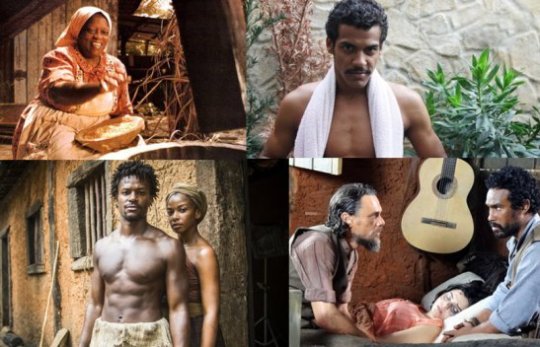

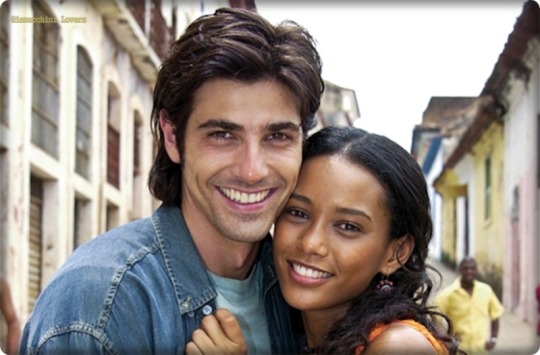

Caption: Typical cast in Telenovelas from different Latin American countries. Most actors, especially main actors are white of European descent. Light-skinned mixed descendants are the second most prominent in certain countries, in some others even they are few. People of predominate African and Indigenous ancestry are usually secondary characters or extras, often playing negative or non-essential roles.

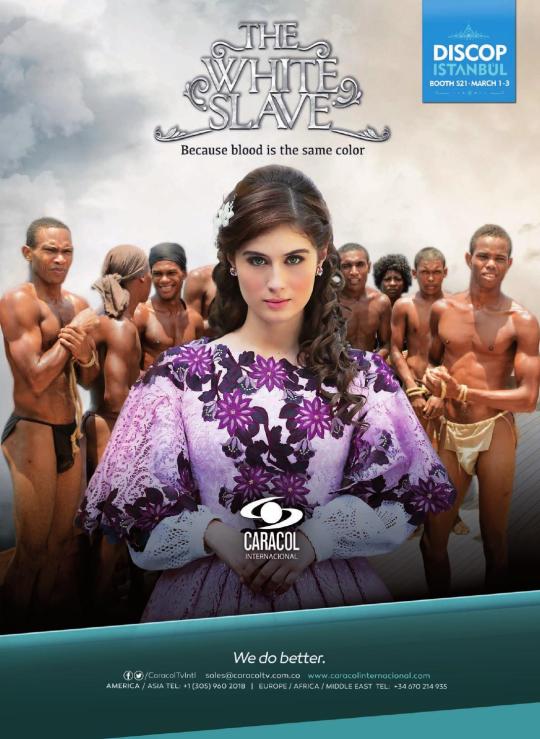

Caption: People of predominate African and Indigenous ancestry typically play maids, criminals, slaves, “non-acculturated” Indian roles (to stress that they’re “unlike us”), and other stereotypical roles. Or the role of the supporting friend to the white character. Black females whenever playing an important role, especially in Brazilian soap operas, are often portrayed as being “saved” from their condition once they find their white prince-charming, a narrative that has its origins in colonial literature.

Sometimes even stories focusing on slavery or colonization have non-Indigenous/Black actors playing them.

Caption: The first telenovela “White Slave” was about trans-atlantic slavery in Colombia, but the whole show was focused on a rich white girl who was sold into slavery and raised by formerly enslaved Africans who escaped to Maroon settlements. The rest of the examples are of white or light skinned-mixed-race people playing black and Indigenous characters.

Fashion

It’s not a surprise that Canada is cold, especially in the winter time, and because of this Canadians are well prepared for such a climate. The piece of fashion that I have incorporated into my own fashion while living in Canada is that of the toque (Cornell, 2012, Sept. 10). The toque is a national symbol of Canada and most Canadians wear them throughout winter. It is believed that the fashion of wearing a toque in this country started with the Bois-Doi-Couers, fur-trappers, often of Metis descent, who made up the first generation of contact between European and Indigenous people (Wikipedia contributors, 2018, June 6). This is why I think it is a quintessential item in helping me adapt both to the climate and the culture/history of this nation. The toque has had a great impact in my life by keeping me warm from the harshness of Canadian winter.

Caption: A Catalan French man wears a type of Phrygian styled hate popular in Southern France and Spain, the influence for the Canadian toque.

Food

Food? What can I tell you about my love for food and the various cuisines of the world. The GTA is one of the most multicultural regions of the world and it has one of the most diverse selections of "ethnic" restaurants, spanning from Uyghur all the way to Chifa (Chinese-Peruvian) dining establishments. Wherever I go, I can't stop myself from being influenced by ingredients and dishes from around the world, for example using loads of Angolan piri piri hot sauce in most of my meals. Toronto like my mother's native Sao Paulo share two of the largest Italian diasporas in the world, and because of this I have greatly been influenced by pasta (Veccia, 1984, pg. 4-12). Due to Italian immigration, pasta has become a staple of the cuisine of Sao Paulo, and it has impacted me greatly because it's been one of the main sources of carbohydrates in my daily life (Coughlin, 2013, Sept. 13). Interestingly enough, there are many legends and theories as to how pasta got to Italy, ranging from Marco Polo introducing it in the Middle Ages, towards the more accepted belief of early Nomadic Arabs spreading it into Europe (Avery, 2012, July 26). Which shows how vastly different cultures have been interacting with each other for hundreds to thousands of years via things like trade routes.

Caption: Brazilians of Italian descent during a folk festival. WIth them are popular dishes brought to Brazil by immigrants from Italy such as pastas, polenta, and cured meats.

Architecture

Studies show that architecture can have both an emotional and psychological impact on us, and I have personally known this to be true (Weller, 2016, Sept. 15). Growing up in Cuba I live on a block where houses were all attached to each other and the road was narrow. Whenever you would walk out of your house the whole street was socializing with each other; people played dominoes, had street parties, and regularly sat around socializing outside as fellow neighbours. This scenario gave me a sense of community, belonging, and a frequent dose of socialization as a child. Then, for some time, I moved to Miami in the United States to live with cousins. They lived in suburbs with wide streets, long back-yards, and houses that were quite a spatial distance from each other. These suburban designs made me feel very isolated and distanced from everyone living around me outside of my family. There wasn't the same feeling of community I felt in the densely populated neighbourhoods in Cuba, where although it could sometimes feel crowded when all the neighbours were out, it always gave me a sense of social belonging and a sense of knowing my neighbour on an intimate level. Later on, living in Canada and working in the construction industry, had once again given me a chance to encounter something that I saw as North American, due to the reason that such suburbs do not exist in my own country. However, this time around it was not the suburbs themselves, but the exurbs; which as we have learned in this unit are the result of greater urban sprawl, and a headache on our environment according to some environmentalists such as David Suzuki. In the exurbs, such as Milton, I discovered something else that had a negative psychological impact on me; tract housing. Although in Canada they're not as bad as some parts of the U.S. or places like China and the UK, they have left a horrid impression on me, due to the fact that most of them look the same and are designed in the same way. It gives a type of robotic, cold, homogenous, collective feel to them. Paradoxal, considering the very non-collective makeup of society in these types of environments (despite how they're portrayed in the media) (Preswitch, 2017, March 16).

Caption: Tract housing. This is depressing.

Caption: Markham, Ontario.

Caption: Most streets both in urban and rural Cuba are close together.

Caption: There are some rural areas with very isolated types of houses, called Bohios, with large plantations or fields for farming. These are usually occupied by descendants of Spaniard/other European peasants who were encouraged to settle in Cuba in rural areas in the 19th century, in order to inhabit areas that were very isolated and were often perfect environments for “Maroon/Palenque” runaway slave) settlements. Most of these farmers and their families have settled in less isolated rural areas where housing is similar to the urban areas or in proper urban areas.

Caption: Most Cubans socialize daily on their neighbourhood street or block. Since until very recently the state owned all property, many people began making businesses from their homes. So often a local business is run on the street or inside the house of a neighbour, thus the person running the business will mostly have clients who are neighbours.

Caption: Cubans hang on their street daily. Often playing card games and dominoes in front of their houses, on the street.

Caption: Community parties and Lukumi (Afro-Cuban deity) and Catholic saint processions occur frequently among neighbours/people on the same block.

Leisure

Leisure activities with origins from around the world are another way you can experience the GTA and Canada as a whole. It's difficult to not to know an urban-dweller that hasn't partook in Japanese Karate, Afro-Brazilian Capoeira, or Hindu Yoga, and I have partaken in various forms of all three activities myself. However, the most influential forms of past-time, would have to be two from my own childhood, both activities have origins in China but have had different impacts on me growing up. Cuba has a large Chinese descended population originating from indentured labourers that were brought to the island at the end of the slave trade (Lopez, 2013, June 10, pg. 50-52). Most Cubans of Chinese ancestry have assimilated into the general population, but many of their cultural traits were infused into the general culture of the nation. Growing up in Cuba, one my best-friends was a Cuban of Chinese ancestry and he and I would often play Mahjong, which is a tile-based game that was developed in China during the Qing dynasty (Lam, 2017, July 28, pg. 11). I've mentioned before Cubans love playing dominoes, and mahjong has many similarities to dominoes. This impacted me because it created a lot of fond memories, and the nostalgia of them hit me every time I play the game in the present. Another example of a Chinese leisure activity that has a lot of popularity in Cuba is that of Tai Chi, which has origins in Taoist philosophy (Wong, 1996, pg. 3). Tai Chi is an activity my grandmother often partakes in, it brings her a lot of joy and opportunity to stay healthy in her elderly age, while being able to socialize with friends and neighbours. It has impacted me because it not only has brough such joy to my grandmother's life, but also helped me bond with her while partaking in it alongside her. In my opinion, it's a great way to get the aging baby-booming population to gather together, work on their bodies, and receive pleasure and the positive psychological benefits which are said to come from partaking in the activity.

youtube

Caption: News segment about Little China in Havana, Cuba.

Caption: Cubans of Chinese descent play mahjong

Caption: Elderly Cubans partaking in Tai Chi

Final Thoughts

In a globalized world and a multicultural region of earth that the Americas are, it's close to impossible not to partake or enjoy of a culture that is different from your own. Often, we don't realize how the socialization process might impact us. How the people and cultures we’re around could shape the way we think and behave, even if its contradictory to our own personal culture. As I have presented above, anyone living in the Americas from Canada, to Cuba, and Brazil could be influenced and impacted by the entertainment, culture, fashion, foods, architecture, and leisure activities of cultures other than their own, in the way I have been. These cultural influences on my life have made me the person that I am today, and have made me appreciate being the global citizen of the world that I am. As the world is changing and people around it open themselves up more to humanity; I hope that people are able to share their cultures more prominently. My only wish is that we go by it in another way. Because like many critics we have read about in this unit, I do unfortunately believe that when culture is globalized it can easily be warped into some type of manufactured, whitewashed, Americanized version of what it originally was. It would be unfortunate if this pattern continued. What is the solution to keep that from happening? I don't think we really have one yet..

References

Avey, Tori. (2012, July 26). Uncover The History of Pasta. Retrieved 7:26 pm., August 28, 2018. From: www.pbs.org/food/

Clarke, Colin. (2018). Mexico and the Caribbean Under Castro's Eyes: A Journal of Decolonization, State Formation and Democratization (22-24). New York City: Springer International Publishing.

Collier, Simon, Thomas Skidmore, Harold Blakemore, eds. (1992). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Latin America and the Caribbean, 2nd ed (pg. 22-34). New York: Cambridge Univ Press.

Cornell, Kari. (2012, September 10). Knitting Hats & Mittens from Around the World: 34 Heirloom Patterns in a Variety of Styles and Techniques (pg. 5). Minneapolis, USA: Voyageur Press.

Coughlin, Jovina. (2013, September 13). South America’s Little Italies. Retrieved 7:19 pm., August 28, 2018. From: https://jovinacooksitalian.com

Lam, Desmond. (2014). Chopsticks and Gambling (pg. 11). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Lopez, Kathleen M. (2013, June 10). Chinese Cubans: A Transnational History (Envisioning Cuba) (pg. 50-52). The University of North Carolina Press.

McAuslan, Fiona. (2010). The Rough Guide to Cuba (pg. pg. 409-413 and 523). London, England: Rough Guides.

Moreno, Carolina. (2017, March 13). This Latina Is Calling Out Telenovelas For Being 'Overtly White'. Retrieved 05:19 pm., August 28, 2018. From: https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/entry/this-latina-is-calling-out-telenovelas

Preswitch, Emma. (2017, March 16). Canada's Seniors Live in Suburbs, And That's A Problem, Says New Report. Retrieved 8:01 pm., August 28, 2018. From: https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2017/03/16/seniors-canada

Veccia, Theresa R. (1984). Families on the Move: Italian Emigration to Saõ Paulo, 1880-1914 (pg. 4-12). University of Wisconsin--Madison.

Weller, Chris. (2016, Sept. 15). There may be an evolutionary reason suburbia feels so miserable. Retrieved 7:48 pm., August 28, 2018. From: www.businessinsider.com/why-suburbs-are-bad-2016-9

Wikipedia contributors. (2018, June 6). Toque. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 01:19, August 29, 2018. From: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Toque&oldid=844733269

0 notes

Note

idk if you've thought about it, but is it possible that you fetishize korean culture/fcs? even possibly some korean rpers in the rpc

Me? If an actual Korean person came off anon and told me I was then I’d absolutely listen and do better. But I don’t think that I do. Granted, I only have one Korean friend in the rpc and they’ve never indicated they find me fetishizing. That’s the furthest thing I aim to be. I mean, I call them gorgeous all the time, bc they are, and they call me that and all our other friends in our Skype group chat. But if they were like “look bitch” I’d fix myself immediately. I really try hard to not cross the line because I see how easy it is to go from “interested in learning” to coming off as “fetishizing.”

First off, it IS something that has crossed my mind so I try to be very careful not to actually be That Person. I studied the language in college that one semester I could afford, so I am invested in learning the Korean language and part of that means consuming as much Korean media as I can to learn. This may be very hard to believe but I honestly was not a kpop fan until after I decided that one of my main languages of focus would be Korean.

I DO admittedly use a lot of Korean faceclaims in RP, but that’s also because most of the media I consume is Korean or in Spanish. Because I want to learn those two languages. Because I’ve wanted to teach English in South Korea for years, and as an American, I feel I should learn Spanish to better communicate with our growing Spanish-speaking population.

There is a huge lack of diversity in RP so I like to use POC fcs as much as possible. I HAVE noticed that I do use Korean FCs a whole lot (because they have so many gifs!!! And I’m a fan of Korean dramas and film so of course I’d see an actor or actress and be like WANTED. FC.) so I’m committing to diversifying my diversity. I originally started RPing with Deepika Padukone as Emmeline Vance and for a while I either used her or Anushka Sharma so I’d like to use more South Asian FCs again. Like, I’m just honestly not familiar with American and British celebrities at this point to use as FCs. I mainly watch Asian dramas and Latin American telenovelas.

I’ve had a message in the past about my “Korean” tag but like. It’s just Korean language stuff? And I use it to build vocabulary and stuff?

Idk man, I’m white so I really don’t much of a voice in this conversation, and rightfully so. But yeah. I DO have an interest in Korean culture because I hope to live there as a teacher after I finally afford college and get my bachelors’, and I don’t want to be a shitty foreigner who only learns cab and restaurant Korean. My goal is fluency - maybe I’ll never be able to discuss politics in Korean, but I’d like to keep up in daily conversation and make and understand jokes and wordplay - both in language and cultural norms. But it’s not like a “lol so Asian” kind of interest.

I get how my reblogging gif sets of kpop idols could be misconstrued as fetishizing, because that’s a signature move of Koreaboos, but I don’t see how that act in and of itself constitutes as fetishization.

If an actual Korean wants to message me off anon and call me out, please do. I DO get how just popping on my blog for a minute can give that initial “WAIT” red flag because of Rosé from Blackpink as my icon, the lyrics from Lisa’s rap in Boombayah, and a lot of Korean music and tv content, because I admit that’s common with people who are fetishizing. But if you’re around a while I’d hope it’s clear that’s not the case. Again. I’m white so I really don’t actually have a say in this.

So any Koreans who want to call me out, please message me off anon so I can do better.

0 notes

Text

For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black

Pollyanna Rodrigues De La Rosa, who only recently began identifying as Afro-Latina (Photo: Roberto Caruso)

Pollyanna Rodrigues De La Rosa sat in the back of a cab, on her way to her favourite Toronto Latin music club, El Rancho. To get herself in the mood for a Saturday night of salsa, bachata and reggaeton, she asked the driver for the auxiliary cord to play “Eres Mia” by Romeo Santos from her phone. The music filled the cab and she sang along, the lyrics flowing smoothly off her tongue in Spanish, the language she speaks at home with her family. The driver raised his voice over the music and asked Rodrigues De La Rosa about her background—but her answer wasn’t what he was expecting.

“I thought you were Black!” he said. Rodrigues De La Rosa, who is part Cuban and part Panamanian, is used to this type of reaction. She stands at just over five feet tall, with big, long, black curly hair. Her dark skin matches her brown eyes, and if you saw her on the street you’d probably have no doubts about her racial identity, either.

But what the cab driver didn’t understand was that while she is indeed Black, she is also Latina. To be fair, Rodrigues De La Rosa didn’t always understand the nuances of her racial identity, either. “For the longest time, I actually didn’t know I was Black,” she says. That’s because, growing up, her family considered themselves Latino.

Though they shared the same skin tone and hair texture, her family never talked about their African heritage—in fact, they preferred to pretend it didn’t exist. Rodrigues De La Rosa’s mother even pressed her about her romantic choices, questioning why she dated Black men instead of white men. And the anti-Black racism was present in her extended family, too. When she visited Cuba in 2015, many of her family members would ask her to straighten her hair for a “better” look.

Between her family’s Latino identity and the anti-Black rhetoric she internalized, Rodrigues De La Rosa questioned whether or not she identified as Black.

Then, in 2015, she discovered a term on social media that she truly felt described her: Afro-Latina. The broad definition is simple—someone who identifies as Afro-Latina, Afro-Latino or the more inclusive and gender-neutral Afro-Latinx is Black and from Latin America. But the term’s meaning is much more political.

In these communities, which have a deep history of anti-Black racism, Afro-Latinx refers to “someone [from the Latino community] who reclaims their Africanness and Blackness, which for so many years was erased,” explains Columbian-Canadian academic Andrea Vasquez Jimenez, the co-director of the Latinx, Afro-Latin-America, Abya Yala Education Network (LAEN). “Utilizing terms such as Hispanic erases our Blackness.”

While Rodrigues De La Rosa may have felt like she stood out among her peers, she is actually part of a large cultural community. A quarter of the Hispanic population in the U.S. identifies as Afro-Latino according to a 2014 study. (Similar data is not available in Canada in part because though the census includes Black and Latin American as visible minority categories, there is no category combining the two identities. Respondents can write in their own classification, or mark all the categories that apply, but the data is counted towards the Black and Latin American categories separately.)

“I get looked at all the time when I start speaking Spanish. It’s still a culture shock, especially to old farts. I quickly let them know that there are Black people in [Cuba and Panama],” says Rodrigues De La Rosa, adding that people often seem to think that it’s impossible to be both Black and a Spanish-speaking Latina.

“When I heard the term Afro-Latina, as sad as this is going to sound, it was the first time I thought I was considered Black,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa. “I loved it.”

Unlearning anti-Black racism as an Afro-Latina

People like Rodrigues De La Rosa are why Jimenez started LAEN. She made sure the organization was a space for Afro-Latinx people to not only have a voice, but learn about their heritage.

“Blackness is global. An extremely high percentage of [people from Latin America] have African ancestry. The identities of Blackness, Africanness and being Latinx are not mutually exclusive,” says Jimenez.

The African diaspora originated with the transatlantic slave trade, when European colonizers dispersed millions of people from Africa to North America, South America and the Caribbean. And regardless of where slaves were taken, sexual violence was common. “This is the most f-cked up part, I don’t know if my Spanish ancestor loved my great-great-great-grandma or raped her,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa.

The intersectionality of Afro-Latinx people can get even more complex, especially for people like CityNews reporter Ginella Massa, who wears a hijab and is from Panama.

“Often, in the realm of my work, my Muslim identity is discussed; my ethnicity or my heritage are rarely ever mentioned,” says Massa. When she made headlines in 2016 for being the first hijabi news anchor, the coverage described her as a Muslim Canadian, but the Afro-Latinx aspect of her identity took a back seat.

CityNews reporter Ginella Massa

Even within Canadian Afro-Latinx communities, positive discussions about embracing all aspects of this intersectional identity are rare.

“Because of anti-Black racism, many folks don’t necessarily speak nor highlight our Blackness within families,” says Jimenez.

That’s especially true among older generations of Afro-Latinx people, who have internalized centuries of institutionalized anti-Black racism. Massa says her family’s Blackness was rarely discussed at home. Her family only focused on their Latin heritage.

“My grandmother, I can say this certainty, would never identify as Black,” says Massa. “I’m not sure where she got this from because to look at her, you would say she is a Black woman. But there is this obsession with light skin and desire to distance ourselves from Blackness.”

For Rodrigues De La Rosa, learning the term Afro-Latina was the catalyst that allowed her to understand her who she really was. She was tired of people constantly denying her parts of her heritage—but in embracing this term, she also had to go through a process of unlearning the anti-Black racism rooted in her community.

As she learned more, Rodrigues De La Rosa also tried teaching her family about their Afro-Latinx history. But it was challenging, especially since her mother, who grew up in Cuba, was ridiculed by other Cubans for her darker skin and tightly coiled hair.

“I’ve had to teach my mother to love herself more,” she says.

Amara La Negra and Afro-Latina celebs stepping into the spotlight

Celebrities such as Jennifer Lopez, Gina Rodriguez, and Camila Cabello are readily identified as representations of the Latinx community in Hollywood—yet celebs like Zoe Saldana, Orange is the New Black‘s Dascha Polanco and Cardi B are often denied their intersectional identity and instead solely seen as Black.

Earlier this year, reality TV star and singer Amara La Negra, whose parents are from the Dominican Republic, reignited the conversation about Afro-Latinx identity on Love and Hip Hop Miami. In the debut episode, La Negra and producer Young Hollywood were discussing ideas about how she should change her image to better promote her music. La Negra insisted her look represented her Afro-Latina heritage. In response, Hollywood proceeded to question her identity by asking, “Hold on! Afro-Latina? Elaborate, are you African or is that just because you have an afro?”

Reducing an identity to a hair type exemplifies why the Afro-Latinx community struggles with their identity. What Hollywood said demonstrated the common misperception that someone can only a singular racial or cultural identity, which for people like La Negra and Rodrigues De La Rosa is not the case. Immediately after the conversation aired, social media feeds were filled with discussions about what it meant to be Afro-Latinx.

“It’s annoying the fact I feel I always have to defend myself. Defend my race, defend my looks, defend my fro… so if I want to wear it a certain type of way that shouldn’t affect who I am as a person or my music,” La Negra said at the reunion episode.

youtube

The type of representation La Negra is bringing for Afro-Latinx women was totally absent from Rodrigues De La Rosa’s childhood. Growing up, she remembers watching telenovelas on TLN. In all the Spanish-language dramas she watched as a child, she doesn’t remember seeing a single Black actor. Celebs like La Negra are changing that.

“What Amara’s trying to do is, she trying to show that’s there are all types of Latino women, she’s showing the darkest shade,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa.

What’s in a name?

With her newfound sense of identity, Rodrigues De La Rosa is now confident in herself to identify as both Black and Latina—and sets people straight when they question her background.

“Now when I say a sentence in Spanish and people be like ‘Oh my God you speak Spanish? I thought you were Black!’ I don’t find it surprising, I find it ignorant. I choose to enlighten them,” she says.

Her struggle with identity has become less about unlearning her internalized anti-Black racism, and more about educating others every time they question her ethnicity or race. Rodrigues De La Rosa will probably always face questions from people who don’t understand intersectional identities. But that doesn’t stop her from letting them know she exists, and so does the Afro-Latinx community.

Related:

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Ellen Asking Constance Wu “Where Are You From?” Could a DNA Test *Really* Help Me Figure Out My Biracial Identity? Anyone Can Participate in Caribana, and Maybe That’s a Problem

The post For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black appeared first on Flare.

For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black published first on https://wholesalescarvescity.tumblr.com/

0 notes