#all jokes of course she's been queer coded since the first movie

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

so glad they made phoebe spengler queer purely because if she did all that over a MAN? i'd be so disappointed. for melody though? that's just an integral part of being a baby gay

#all jokes of course she's been queer coded since the first movie#in the sense that everyone in my life tells me i'm just like phoebe#i look more like her than her actor out of costume it's BAD.#i really need more people talking about this movie it went so hard#phoebe spengler#ghostbusters#ghostbusters afterlife#ghostbusters frozen empire#melody ghostbusters

732 notes

·

View notes

Note

why is there so much denial of Will being gay?? Like, nothing Will has done has shown him to be anytging but possibly gay. Like, nobody thinks he'z gay because he's a nerd that doesn't have a girlfriend!! We think he's gay because of all the fucking subtext!!!!

There are a few reasons for this, and they’re all (for the most part) rooted in homophobia. 1) There are those who (may or may not) notice the subtext, but ignore it with the excuse of “he’s too young; stop sexualizing him!”. All while shipping lumax, and mileven. Whether they want to admit it or not, this is homophobic! They view (subconscious or otherwise) being queer as inherently sexual, dirty, and adult. And that only straight relationships can be pure and innocent and based on compatible personalities. Straight kids can have innocent crushes (but in their eyes) queer kids can’t- they may not even exist, to them.

2) There are some mileven shippers (who whether they want to admit it) hate Will, because the possibility he has powers or is gay- threatens their precious het ship. Because a lot of them don’t see El as her own person (just a part of their ship) or a vessel for being a badass with powers. They don’t appreciate her for the nuanced character she is. They either get angry at the idea of Will being gay or having powers, or are only happy with him being queer if he’s sad and in an unrequited one-sided love/ or is single forever. Or they’ll say “why don’t you just ship him with someone else… like Dustin?” Ignoring the fact Dustin hasn’t been queer coded like Mike (or had romantically coded scenes with Will), or that people ship byler for Will and Mike, not cause it’s simply m/m. I mean, can you imagine byler shippers saying ‘Just ship El with Dustin, it’s a guy and girl… it’s practically the same thing”? No, of course not! It shows their bias- and how they feel privileged and entitled to their straight ship even though there are millions of similar ships in media to choose from- unlike queer ships which are far and few in between. However, we’re supposed to be the ones who pick another option- and are told our ships are ‘all the same’. Whether they are aware of this bias, they consider queer ships a joke, and all the same.

3) Those who relate to Will and his struggles, hate the idea of relating to a queer character. There is a reason why shows like ‘Will &Grace’ in the 90s were popular, but even today the second a character who people assumed was straight is revealed as lgbt+ viewers get angry! It’s because they feel ‘tricked’ into liking, relating and empathizing with a character that they would otherwise have immediately put in a ‘box’ and distanced themselves from . Whether they are aware of it or not, they would immediately attribute stereotypes to them and never try to empathize with them, because ‘they’re gay, and ‘how can I relate to that’? They don’t want to relate to them (because subconscious or otherwise) they think being gay is bad or just too foreign.They don’t see queer people as full-fledged people. They’re just gay- nothing more.

Which is why when they angrily say “he’s just afraid to grow up, HE’S NOT GAY!” They are essentially saying a gay, abused kid, who has ptsd, and was violated by the MF (and was also hinted m**ested by Lonnie too) can’t be afraid to grow up, since he lost his childhood. Only straight people have these type of human-fears and characterizations!

Forget the fact, that Will also wouldn’t want to grow up- because than he’d have to acknowledge his sexuality (at a time where all you heard about gay men was they were evil , mentally ill, going to hell and dying of aids as a punishment by god). Not to mention Will’s ptsd and the fact he lost 2 years of his childhood on top of that.He even says “I’m not … going to fall in love” (not convincingly) , right after the movie date with Mike.

4) They’re so used to straight media, and everyone being presumed straight and having media catered to them (the straight audience)- That they’ll ignore or miss every hint there is a queer character.

So what are the hints of Will being gay (or at least- some other lgbt identity.

Called many homophobic slurs since s1 ( specifically ”queer, fag, fairy, and gay”) by his dad and bullies. Jonathan in s1 tells Will to “not like things just because people tell you you’re supposed to, especially not him” ( ‘him’ referring to their dad). Is positioned behind a rainbow apple poster in the av room (ref. to Alan Turning the gay creator of computers), dances with a girl with a rainbow hair-clip, has rainbow bandaids, has his mom says she’s ”so proud” (lgbt+ pride ref) of the rainbow ship he drew . When Will disparages himself as a “freak”, Jonathan asks Will, who would you rather be friends with- David Bowie (who was openly bi since the 70s) or Kenny Rogers? Will says Bowie, and Jonathan agrees saying “see, it’s no contest”. In the pitch to netflix the Duffers described Will as having “sexual identity issues”. In the leaked s2 snowball script it says “he’s not looking at the cute girl- but Mike.”

All of s2 directly paralleled ‘romantic s1 mileven scenes’ to ‘supposedly platonic byler scenes’. No joke, they had identical scenes, with almost identical framing and dialogue, but it’s all dismissed as friendship (even though the scenes are identical).Byler was also paralleled to Jancy, Stancy, Jopper, bob/joyce and others. . You can headcannon Will as whatever you want, but like it or not- Will is queer and m/m! We could debate his exact queer sexual identity , but Will was never written and will never be written to be ‘straight’! Stay mad!

If Will was Wilma, the majority of the fandom would be byler shippers. Think about it! Mike having byler scenes that are identical to s1 mileven scenes, and then additional unique byler scenes. Mike staying by Wilma’s side 24 hours a day for several days (not even changing clothes), carrying her out of the hospital, grabbing her hand (with a zoom in shot),constantly asking her if she’s okay at least 5-7 times, putting his arm around her twice, being the only one who could tell something was off with her (and it wasn’t her normal type of quiet). Calling and running all the way to her house and banging on the door to check on her, desperate. Proclaiming “i’m the only one who cares about Wilma!” Watching her sleep cause he’s so worried, that shed scene reminiscing about how they first met in perfect detail, saying “I asked, I asked if you wanted to be my friend. You said yes, you said yes. It was the best thing I’ve ever done. (like a marriage proposal)” The “crazy together” scene. Them being close since they were 5 vs the girl he knew for a week (but is somehow in love with?). If the witness said about El in s1 , “ same height… it could be the Byers girl”, instead of ‘boy’ (pointing out the resemblance). Mike getting into fights and getting upset (almost crying) about the bullies insulting Wilma. Mike having a whole binder of her drawings and caressing one of the drawings, after he thinks she died. Being the only one of her friends to stay awake at the hospital, waiting for her to wake up- so he can see her and hug her first. Almost everyone would be team byler if Will was a girl- they probably would of started shipping it the second Wilma stared at him and was the only one who didn’t lie to him, in the first ep! Another parallel to El!

And again think about s3 if Will was a girl.They paralleled the (comedic) mileven breakup vs (the sad/serious) byler breakup. Then Mike just complained and burped on the couch vs apologizing to Willma multiple times/even going into a storm to apologize a 2nd time (and to ‘talk’). Willma having a breakdown over the fight vs El laughing and high five-ing Max after.The shed vs the pool shed scene- “best thing I’ve ever done” vs “you’re the most important thing in the world to me”, “blank makes you crazy’ (as El stares confused) vs “crazy together’ (where Wilma says ‘yeah, crazy together). Mike going on ‘movie dates with Willma all the time’ right after making out with El. The last mileven kiss where Mike has his eyes open the whole time, doesn’t kiss back, and says he doesn’t remember saying “I love her” to El (and doesn’t say ‘I love you’ back). Right after having a talk with Wilma about playing games when she comes back (the crux of their fight). Mike getting excited that he’ll be able to visit El and Wilma on Thanksgiving and them visiting him on Christmas (those are holidays where family usually introduces their S.O.) Having the last scene of Mike, be him looking back at Wilma’s house, and have that whole monologue in that scene be about “feelings changing”, and then he goes to hug his mom like the s1 byler scene where he thought Wilma was dead. And that’s not even all the scenes- and every time byler won by a landslide. If Will was a girl, it would be obvious writing on the wall, that Mike would eventually choose Wilma over El by the end of the series.

But since they are 2 boys, we’re delusional, because queer kids don’t exist … apparently.

400 notes

·

View notes

Text

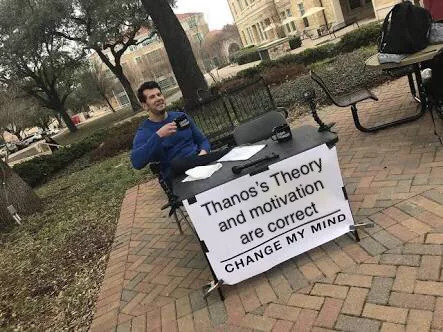

tl;dr: nope

I got a couple of anon asks about this, and I’m also tagging @twist-shout-and-shells because they asked me to, but I have to say - I don’t know anything about comics, I don’t know Marvel at all, so this review is just a meaningless rant. Like, I know so little about this universe that the first superhero movie I ever saw in my life was Thor, and the only reason they got me was because my mythology-loving ass assumed this would be about the actual god, you know?, so that was a very confusing two hours. Anyway - after this, I’m done with them. The ridiculous hype campaign they created around Infinity War actually activated my crow brain, which means I rushed to the theater because I was sort of expecting this would be a shocking masterpiece and any spoiler would ruin it for me, and - yeah. Never doing that again. Because, whatever - they do manage to come up with some good writing from time to time, and Black Panther’s success had made me hope they’d finally recognize that a solid, coherent and meaningful story is really the first thing you need, but apparently not?

Ugh.

Anyway, here are main reasons why I didn’t like Infinity War.

1) No, we don’t need a new plague

Problem number one with this movie is that it fails to take into account that our IQ as a people has dropped about twenty points over the last thirty years (and I’m not even joking) and that means even a guy nicknamed ‘Mad Titan’ is actually given the benefit of the doubt (I don’t remember anyone thinking Hela might have had a point, but then again, women are known to be emotionally compromised at all times, right, so all that rage was probably PMS and crazy bitches, amirite?, can’t live with them, can’t live without them). And here, predictably, is the result:

I even checked Breitbart so you wouldn’t have to and while they seem confused as to whether they should support this movie or not (don’t watch because Captain America is played by ‘Comrade Communism’, do watch because Chris Pratt is a Good Christian Man), it’s still clear to everybody over there that Thanos, “an environmentalist wacko obsessed with salvaging the natural resources of the universe” is “espousing liberal jibberish”.

So, I’m going to keep it short and mostly sourceless because I saw a lot of people discussing this, but just to be clear: yeah, it is worrying that human population has basically tripled in thirty years, but the correlation ‘more people = more damage & fewer resources’ isn’t as clear-cut as some like to think. Also, research shows that women being recognized as human beings - that’s the actual way to solve this problem (see also x, x), which means that if Thanos had meant business, he could have used those frwaking stones to build schools and family planning centres.

2) Your plan against evil can’t be just saying no

This is probably what bugs me the most both in fiction and IRL: saying ‘Trump is a moron’, ‘capitalism is bad’ or ‘genocide is wrong’ is not a political program. It’s a moral stance, and kudos to you, but if you want to make the world a better place, you need a lot more than that. But, nope - IW fell into this trap with such relish I can actually believe no one saw this as a problem - at all. When Thanos pointed out, rather smugly, that decimating Gamora’s planet had led to a new era of happiness and prosperity, she didn’t react in any way. We never saw Tony or Shuri mentioning the outlandish, extravagant idea that better and greener technology could actually save us all. We never saw anyone point out that when the richest 1% own half the world’s wealth, wiping out half of a Nairobi slum isn’t likely to do much for the environment. I guess it wasn’t relevant to the plot?

3) Turning your audience against the good guys = dick move

That said, our planet is objectively in bad shape, and writers and artists who are (or like to think of themselves as) engagés are more than welcome to discuss this - for all her faults, JK Rowling did that to perfection in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, focusing on the importance of conservation and taking a clear stance against animal trafficking. Other movies, of course, went a lot farther than that: my movie rec of the day is Okja, a masterful and soulwrenching look at how capitalism manages food production. But IW, on top of everything else, manages to be an anti-green movement movie? As if that was needed in any way? Apparently comic!Thanos’ goal was to impress Lady Death or something, and maybe they should have gone with that, because to me, movie!Thanos’ plan sounds like an ill-conceived and unfortunate parody of the green movement. In fact, eminent biologist E. O. Wilson’s Half-Earth explores this exact possibility - which is not about killing off 50% of the population, thank you very much, but about improving agriculture and urban structures so we can leave 50% of the world to the rest of the ecosystem. And maybe it’s just me, but isn’t it a bit weird the book came out at about the same time when IW’s script was being written? I try not to be a paranoid nutcase, but come on. Because what the movie does is that it turns Thanos into a sort of green Hitler whose only focus is the environment (“But he was a vegetarian!”), cue the creepy final shot of him going all ‘Schwarzy in the forest’ surrounded by clean-water creeks and happy animals while we are left counting our dead. The metaphor couldn’t be more obvious, and to be honest it is most unwelcome. Time and place, guys? I really haven’t seen something so revolting since I got to the end of the Da Vinci Code and realized atheists were the true monsters all along.

4) Being a hero doesn’t mean saving your friends

So this is starting to become a trend, and seriously, enough. If you’re a hero, then you need to think of something greater than yourself, and this is why your life will suck and suck and suck until your untimely death. Deal with it? And I can understand Loki giving up the Tesseract for his brother, because he’s always been more of an anti-hero than a hero, and his morals are shot to hell in any case, and I’ll forgive Dr Strange because he clearly saw something we didn’t, but what the hell was Steve thinking? Seriously, I keep seeing posts about how Pure and Noble Steve is, and guys, did we even see the same movie? Bringing Vision to Wakanda meant endangering an entire nation, and thousands of people there paid for that choice with their lives. It’s because Steve insisted in not seeing the big picture - or accepting Vision’s own wishes - that Thanos even succeeded in the first place. If they’d destroyed the stone, Thanos would never have gotten his hands on it, and Wakanda would not have been attacked by a horde of alien demons. Sacrificing hundreds or thousands of nameless (black, African) warriors to keep one (white) man safe is not heroism - it’s cowardice. It’s assuming your own feelings and your friends’ lives count more than the lives of strangers, and this is the exact opposite of how a hero should think. Not that I’m surprised, since Steve already condoned the destruction of half of Bucharest to save Bucky, but whatever. Compare and contrast with Tony, by the way, who first tried to destroy the Time stone, then chose to sacrifice himself to save someone he didn’t even like? Yeah, that’s more like it. #TeamStark

5) Every single woman is defined by her relationship to a man

With the caveat that no emotion, connection or motivation is throroughly explored in IW because it’s an action-packed movie during which people never speak an honest word to each other (relying instead on posturing, movie quotes and sarcastic remarks), here is basically what happens: men have things, and women have men. Tony’s journey is mostly about saving Peter and also sacrificing himself for the world. Steve is all about his friends and various heroics. Dr Strange is a sort of ascetic monk playing the long game. Thanos wants to save the universe or something. And Vision is on a quest towards humanity? Maybe? But the women - Gamora is important because she’s Thanos’ daughter. Scarlet Witch is important because she loves Vision. Natasha (I think she’s in the movie? I don’t actually remember if we hear her speak) is on Cap’s side because Cap. Pepper only appears to remind us of what Tony has to lose. Exceptions to this rule include Shuri, whom IW didn’t quite manage to destroy; Loki, who was always female- and queer-coded, so I’m not surprised he ends up dying for the handsome and suitably Aryan hero; and arguably Starlord, who mostly fights for Gamora (what is a virtue in a woman, however, is a weakness in a man, because Starlord ends up fucking up the plan because of his love for her). And I know they probably tried to compensate for the complete lack of women in the movie by highlighting how powerful Scarlet Witch is and focusing so much on Gamora, but I’m an annoying person, so that didn’t work for me. Because, again, Scarlet Witch is a 2D character plucked directly from a Victorian dictionary’s definition of ‘woman’ (while the menfolk around her worry about the possible demise of the Entire Earth, there she is, channelling all her energy in being a good and loyal companion to her robot husband) and Gamora has no more control over her life in this movie than she had as a child? Her main narrative purpose in IW is to make us feel bad for her boyfriend and father, who’re both driven to kill her (for very different reasons) and suffer for her death (and don’t get me started on Thanos suddenly loving someone and what a stroke of luck, the one person in the universe he gives a damn about just happens to be standing next to him on top of a cliff when he needs to kill her). Seriously, why is it that female characters’ concerns still begin and end with romantic love? This trope that romance is the most important thing for every single woman needed to die, like, yesterday.

6) None of that actually means anything

Look, I’m a sucker of time-travel of any description, but I also think time-travel must be done honestly or not at all. Movies like Back to the Future or Arrival both use time bending to great effect, because the stakes are real and painful and there are all sort of complex decisions facing our heroes. But IW doesn’t care about any of that. The existence of the Time stone is not about ethical dilemmas or even turning up the drama to eleven - the one purpose of that thing is to make us hope that our personal fave is not dead after all, so we’ll keep watching this stupid franchise until the end of times. That finale could have been innovative and heartwrenching, and instead we already know it wasn’t. Samuel L. Jackson is apparently confirmed in Captain Marvel, which will be released next year, and we also know they’re working on Spider-Man 2, Guardians of the Galaxy 3, Black Panther 2 and Doctor Strange 2. Capitalism has very nearly killed the possibility of creating a well-written and gutting story, because the rule is, If it makes money, it goes the fuck on. Hence TV shows which no longer make any kind of sense but we all keep watching out of nostalgia, affection for the characters or dissatisfaction with our own lives, and also franchises which stretch the plot to new and boring limits (for instance, it beggars belief that Tony and Steve didn’t even meet in IW, and their fight never came up at all: I guess we’ll have to wait for IW 2, or Avengers 37: The One with The Talk). And here, again, studios are so greedy that they willingly disregard the fact audiences will reward ‘complete’ stories: for instance, Logan was critically acclaimed and made tons of money, but the risk of ‘permanently’ killing off a beloved character is still considered too high. And playing it safe actually works: IW costed $320 million, which is about 5% of the studio’s budget, and that investment has already been repaid in full (the movie made double that in the first two weeks).

(Meanwhile, 21st Century Fox gained more than one billion dollars from Trump’s TAX REFORM THAT WILL MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN - probably a disappointing amount of money for owner Richard Murdoch, who has a net worth of 15 billion and is known to use some of that hard-earned cash to support laudable & important causes such as the privatization of public education, but hey, we all need to make do and move on, right? Right.)

So this is mostly it. To be fair, IW was mildly entertaining, and I thought they sort of did a good job in juggling twenty leads - we got no character development at all and no meaningful dialogue, but we saw everybody at least once and their lines were funny? Some moments were genuinely good despite a couple of bizarre plot points (I’m still unclear on why Strange didn’t create a circle of fire around Thanos’ arm, and very tired of the overused ‘Yeah, let’s save the most powerful weapons for last’ trope), so I wouldn’t say this was the worst movie ever made, but as I said, I’m done. I’ve given more than enough money to this franchise, so when IW 2 comes out, I think I’ll be a boring adult and watch it on TV as I’m doing my ironing or something. Good times.

#infinity war#iw#iw review#infinity war review#marvel universe#there you go#i think everyone has seen it by now?#here is my take on it#sorry to be annoying

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drag vs Trans and how everyone loses

As I was unable to address it in my presentation, I would like to take the opportunity to use this blog entry to discuss the feud between drag queens and trans women. These are two groups that, decades ago, often shared spaces and common interests, but have since been pushed apart by identity politics. And it is, I believe, this very thing that continues to drive the two groups apart and fuels the animosity between the groups. It is not my intention here to suggest that these two groups should be pushed back together. No, quite the contrary, I would argue that there is an extent to which a firm boundary between the two is useful and perhaps necessary for trans advocacy politics. This boundary may be complicated by the presence of individuals who claim membership in both communities, but, I believe, it does not nullify it nor reduce its necessity to trans advocacy. However, it is not my intention here to address this issue of those who traverse the boundaries, if only because this question quickly becomes one of why people perform drag, a question that is far too complex to attempt to answer within a single blog entry. What I do wish to discuss here is some of the root causes of this feud and to perhaps offer ways that trans women and drag queens can come together as political allies in ways that respect each other’s identities.

From the perspective of many trans women, one of the root causes is a conception of drag queen performances as being, by their very nature, transmisogynistic. They are not the first to level these kinds of claims against the drag queen community. Writing specifically about black men performing drag, bell hooks argued that drag performances seem “to allow black males to give public expression to a general misogyny.” [1] This is an argument that has been repeated by many cis women in criticism towards drag performance (often without the racial specificity) and trans women critics utilize similar logic. For them, drag queen performances are merely an extension of the man-in-a-dress trope that turns the existence of trans women into a running joke in popular culture. However, to conceive of drag performances as always-already transmisogynistic is an over-simplification. Judith Butler, writing in part in direct response to bell hooks, locates these kinds of arguments on the same continuum as reducing lesbian desire as a product of failed heterosexual love. “This logic of repudiation,” Butler argues, “installs heterosexual love as the origin and truth of both drag and lesbianism, and it interprets both practices as symptoms of thwarted love. But what is displaced in this explanation of displacement is the notion that there might be pleasure, desire, and love that is no solely determined by what it repudiates.” [2] While here we again come again to the question of why drag performers perform drag, my only intention here is to argue that the always-already argument is a simplification that blinds us to the subversive potential of drag that can be used to denaturalize the ideology of gender that perpetuates harm against the trans community.

But this is not to say that all drag performances are subversive. Butler herself recognizes this when she states “that there is no necessary relation between drag and subversion, and that drag may well be used in the service of both the denaturalization and reidealization of hyperbolic heterosexual gender norms.”[3] Rather, drag performances may reify or subvert gender ideology, or perform in a way that expresses ambivalence between these two options. Jose Esteban Munoz, in his work on disidentification theory, posits that “Commercial drag presents a sanitized and desexualized queer subject for mass consumption … [that] has had no impact on hate legislation put forth by the New Right or on homophobic [or transphobic] violence.” [4] I might add the caveat that the performances to which Munoz is referring have had no positive impact on hate legislation. Certainly, there is a history of mainstream drag performances actively disseminating transphobic discourses (see, for example, RuPaul’s Drag Race), and these may have arguably had a negative impact on the progress for trans rights. But there is a possibility of for drag that subverts. I think, again, here of Munoz’s work, in which he examines the drag performances of Vaginal Crème Davis, quoting her as saying, “I didn’t wear false eyelashes or fake breasts. It wasn’t about the realness of traditional drag – the perfect flawless makeup. I just put on a little lipstick, a little eye shadow and a wig and went out there.” [5] Further, I think of the film Madame Sata, in which the protagonist performs drag with no regard to passing, fully displaying their typically male coded body.[6] These performances subvert through highlighting the performative nature of gender, removing femininity as always-already attached to female coded bodies. I do not wish to posit this kind of drag as the only way in which to perform subversively, but only as one option.

Here it becomes necessary to address the drag queen community specifically, because it is my belief that the drag community has a responsibility here. Stephen Schacht and Lisa Underwood, in their study of the culture of female impersonators, argue “that any meaningful models of what is subversive must take into account an actor’s explicit intent, the audiences for whom she/he performs, and dialectic between the two.”[7] I have to agree with this. And while, of course, no drag performer can be held responsible for how the audiences read their performances, I do believe it is their responsibility, to cis and trans women, to examine their intentions and their performances and make an active attempt to not reproduce harmful ideology, if not to actively attempt to be subversive. Perhaps more importantly, this responsibility does not stop at the boundaries of one’s own intentions and performances. While perhaps most drag performances that are culpable in perpetuating discourse that harms trans women do so unintentionally and/or out of unexamined intent, there are those who actively and knowingly perpetuate them. In an examination of the drag queens of the 801 Cabaret by Verta Taylor and Leila Rupp, the performers express their worry over one of their own exploring the possibility of identifying as transgender, stating that to do so “means you’ve lost your identity.”[8] A similar sentiment is expressed by Pepper Labeija in the documentary Paris is Burning. In the film, Labeija speaks at length of their belief that being transgender is “taking it a little too far” and expresses thankfulness that they were smart enough to never have a sex change.[9] These kinds of sentiments seem to be rampant within the drag community (see, again, RuPaul’s Drag Race), and any drag queen that wants to be an ally to the trans community has a responsibility to call out their fellow performers for perpetuating these ideas.

Lest we place all the blame of drag queens, however, trans women have a responsibility to drag queens as well. As discussed, a large part of the animosity coming from trans women towards drag queens is the idea that their performances are inherently transmisogynistic. Stemming from that is the belief that their performances are helping to perpetuate the common belief amongst the general public that drag queen and trans woman are synonymous terms and that the latter are, like the former, (typically) men performing a role. But, as has also been stated, drag queens cannot be held responsible for how the audience reads their performances. Given the deeply entrenched nature of binary gender ideology, even the most subversive performances will still be read by some in ways that reify strict and essentializing gender norms. Trans women must understand that the onus of dispelling these ideologies is not on drag queens. As an extension of that, I do believe that there is an extent to which this feud is fueled by some akin to jealousy. The simple, sad fact is that drag queens have, by and large, reached a much higher level of acceptance in mainstream culture. There are those, I have met them, who love drag shows and refer to drag queens as she/her, but will not give trans women basic human respect. This is not the fault of the drag queen, nor is it a reason to attack the performer or the performance. Trans women, stop displacing your aggravation with a transphobic public on drag queens.

This is a very complex topic for a relatively small amount of discussion. I have not endeavored here to solve the feud in its entirety. Rather, my hope here is to have highlighted some of what I believe are the major causes for this feud and offer some ways in which both parties can work towards ending it, possibly towards working concurrently to change gender ideology that harms both groups. As members of the wider LGBTQ+ community, there is, I feel, every reason why these groups should be working together instead of against one another, but we have to stop needlessly fighting each other first.

[1] bell hooks. (2008). Is Paris Burning? Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies (pp. 275-90). New York, NY: Routledge.

[2] Butler, J. (1993). Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion. Bodies That Matter: On The Discursive Limits of “Sex”. (pp. 121-40). New York, NY: Routledge.

[3] Butler, J.

[4] Munoz, J. E. (1999). Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis, MN: The University of Minnesota Press.

[5] Munoz, J.E.

[6] Ainouz, K. (2002). Madame Sata [motion picture]. Brazil: VideoFilmes.

[7] Schact, S.P. & Underwood, L. (2004). The Absolutely Fabulous but Flawlessly Customary World of Female Impersonators. Journal of Homosexuality, 46(¾), pp 1-17. DOI 10.1300/J082v46n03_01

[8] Taylor,V. & Rupp, L.J. (2004). Chicks With Dicks, Men In Dresses: What It Means to Be a Drag Queen. Journal of Homosexuality, 46(¾), pp. 113-33. DOI 10.1300/J082v46n03_07

[9] Livingston, J. (1990). Paris is Burning [motion picture]. U.S.: Miramax

#transgender#social justice#drag queen#drag#trans#identity politics#lgbtq#lgbt#lgbtqia#queer#queer theory

1 note

·

View note

Text

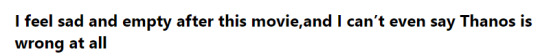

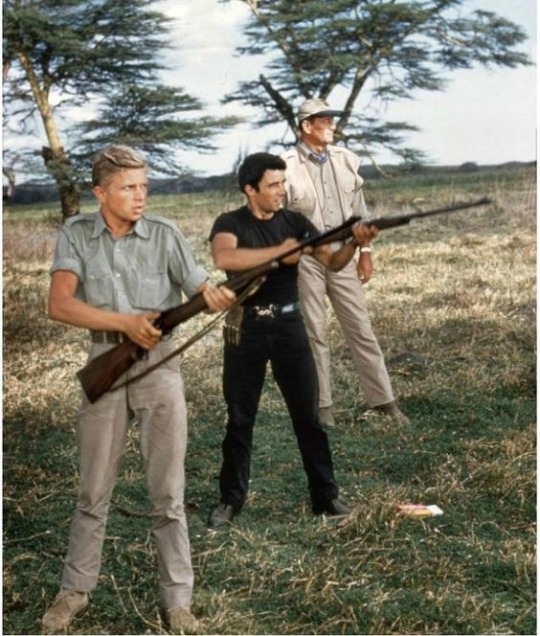

“Hatari!” An example of queer coding in film history

As I watched for the first time in years the movie “Hatari!” a new perspective came to mind, and I discovered a secret my subconscious had been telling me about since childhood. “Hatari!” is a simple, charming kind of romantic comedy-adventure, about a group of hunters in Africa that catch animals and sell them to Zoos all over Europe. The movie is quite forgotten nowadays since it has no big thrills, action scenes, dramatic love story or gross out humor. It is only remembered as one of the decent John Wayne movies. But it turns out, it is also an example of queer coding done right and for the right reasons and contains a beautiful powerful gay “bromance” story.

So, let’s do this.

I know what a lot of you may be thinking. Queerbaiting is never right! But queer coding and queer baiting are not the same. It is only recently that the LGBT community has gained its rights, and even now the representation in media is usually not very good or inexistent, just as with the majority of minorities. But during the 40, 50 and 60 eras things were much worse. Since the beginning of Hollywood, films had to be approved by the censors before they could appear on screen. No extreme violence, no sexual relations, no communist propaganda and definitely no queer content was allowed. However, things got worse when in 1946 the Hollywood Blacklist started. It was then when screenplayers, actors, and directors started to be imprisoned for their beliefs. And until 1960, when Trumbo was actually recognized and accepted back in Hollywood the Blacklist stayed. But even afterward, the witchhunts and censorships continued. Therefore, those who wanted to tell different stories, present outside characters or represent themselves had to use coding and subtext to do so. And thus, queer coding became a loudly spoken secret, just as subtextual communist ideas or sexual tension and innuendos disguised as the fight of the sexes. And “Hatari!” a movie by the great Howard Hawks and released in 1962, made a great and positive use of this, which is why I wanted to use this movie as an example.

The film tells the story of the chief of the hunters, played by John Wayne, who falls in love with a photographer that works for a zoo from Switzerland. At first, it seems he can’t stand her, and he assumes she is going to be trouble. But as their relationship blooms and they even adopt three motherless elephants, it turns out they are quite a good match for each other. Of course, it is not this two characters that interested me in my new viewing of the movie. Although when I watched it for the first time with my father, who loves it, I thought they were the most relevant characters of the story, two other characters caught even then my attention. And it’s about their relationship I want to talk here.

The movie begins with one of the hunters getting hit by a rhinoceros. Immediately, they all rush to hospital, but by the time they arrive, “The Indian” has already lost a lot of blood. It is then when a new character appears. A French guy named Charles Maurey that has heard they’ll be needing a new worker. Of course, Kurt Muller, a German car racer that is part of the hunter’s team, jumps immediately with anger. His friend is “not yet dead”, and so he hits the French guy. However, as it turns out “The Indian” has a pretty rare blood type, and the only person that can transfuse him is the French man. But Charles does not care about the job anymore, he just wants Kurt to ask him for help. Thus their love story begins. Even if very few people will recognize this couple as more than friends, the coding is there.

Charles, who soon will be called “Chips” by his new colleagues, and Kurt are the only male characters in the entire movie that are somewhat sexualized. The female love interests appear almost always fully and usually quite modestly clothed ( the only exception being the time Dallas is “attacked” by a leopard while showering). In fact, you could say, especially if you look at other movies the actresses partook in, that they were unsexualized in this one. In contrast, “Chips” always shows off his muscles under are a tight blue shirt and a pair of “Rebel-without-a-Cause-Glasses”; and Kurt wears the shortest pants with pride, while he unbuttons his collar, and makes the same use of his glasses.

The second time they meet, some days have passed since “The Indian” got send to the hospital, and John Wayne receives a call, telling him that “Chips” abandoned the place after asking for money. Kurt assumes that he has gotten the money for himself and is not going to appear again. But soon after, the French comes by, a rifle that he bought back with the money he asked for in his hands, and ready to apply for the job. After they try him out and realize he’s a good shot, Kurt seems to be quite happy to accept him and even gives him his weapon. “Chips” punches him in the face and asks him afterward: “Do you still want me?”

It was at this point that I first noticed the queer coding. Who would ask if someone still wanted him when he was applying for a job? Funny enough, it was obvious that the reason they did not like each other at the beginning was mare Pride from “Chip’s” side and Prejudice from Kurt’s part. But after this, they become close friends. They drive together in the same car, they wear the same glasses, are always close to each other, “Chips” even safes Kurt’s life at one point… And yes, they also fight for the same girl. You may wonder how that’s possible if they are both gay. However, it was rather usual for queer coded movies to put a female love interest in between “gay acted” characters, in order for the film to pass the censorship. It is obvious if you see the movie that neither of the two men is really interested in the girl they are chasing. They pass more screen time looking at each other than at her, and when it turns out that she is in love with the comedic character, they accept it easily and Kurt invites “Chips” for a drink.

What is great about this movie is that you can easily see when the screen players or director thought, they were being too obvious, as immediately after a very close scene between them comes another one with a female counterpart, or were one is relegated to the background, looking at the other from time to time with apparent longing. They get hurt together, they heal their wounds together, literary in fact, and they are always driving together. By the end of the movie, they both have planned to go to Paris together and stay there until the next hunting season. They apparently both know a girl there. “It’s a good excuse for another fight,wright” says Kurt and then asks John Wayne what his love interest is going to do, therefore comparing “Chips” with the girl Wayne loves.

It is precisely this ending that makes me love the movie more. And for that to be understood we have to see how the queer coding at the time went. When we think about hidden queer characters in classics, usually there are some movies that pop up repeatedly: “Strangers on a train” by Alfred Hitchcock, “Spartacus” by Stanley Kubrick, “Some like it hot” by Billy Wilder… Each of this three examples shows a different kind of typical queer coded character:

“Strangers on a train” was not the only time Hitchcock queer coded main characters. He did the same with the movie “Rope” and the similarities between the men are quite obvious. As much as I love Hitchcock both for his films and his willingness to break molds and fight for acceptance, I have to agree with those that criticize him for making his villains gay. Even in “Strangers on a train”, where the hero is also queer coded, he ends up with a female lover instead of with his villainous gay counterpart. In that sense, “Spartacus”, the movie that helped break the Black List and is all about freedom of expression and the right to be oneself, has a similar problem. Tony Curtis plays a young, attractive and somewhat feminine slave that falls in love for Spartacus, who rescues and takes care of him. But as the story is a tragedy and a reflection of the times Trumbo lived in as he wrote it, everybody dies. Only Spartacus’ female lover survives and runs away with her baby.

And then we have the hilarious “Some like It hot”, that is way more explicit and actually has a happy ending for the two queer coded characters. The only slight problem is that these characters are supposed to be a joke. Their sexuality is supposed to be part of the joke. By stating this, I’m not trying to devaluate these movies. They are some of the best films ever made, touching on impossible themes at the time with impeccable taste and great direction. But they also show the stereotype that would follow gay characters in movies up until now.

There have only been three queer characters in Hollywood for decades: The comic relief, the villain, or the hero with a tragic ending. Nothing more nothing less. And this is the brilliance of “Hatari!” in my opinion. Kurt and “Chips” are anything but gay stereotypes. They don’t have a tragic ending, they are not villains, and they are not there to be a comic relief. In fact, “Pockets” the character that so easily could have been queer coded, is the one that ends up with the girl.

This is the reason I wanted to write this essay. This two minor, overlooked characters of a movie that nobody bothers to remember could easily be the best gay couple that was written during the censorship era. And they end up happy, and they have never been outed before. So this is me pulling them out of the closet.

I hope you like it.

But even if you don’t believe the couple is gay, you can still enjoy the movie, as my family does, because of its light harded humour, great score from Henri Manccini, great screenplay by some of the best Hollywood writers at the time, and beautiful elephants in the room ;)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

More Than 150 Companies Are Hoping This Woman Can Fix Their Diversity Problems

New Post has been published on https://delphi4arab.com/more-than-150-companies-are-hoping-this-woman-can-fix-their-diversity-problems/

More Than 150 Companies Are Hoping This Woman Can Fix Their Diversity Problems

For three days in February, 6,000 of people coursed in and out of the Castro Theater, a 1920s movie palace in San Francisco. They came to hear from Laurene Powell Jobs, Susan Wojcicki, and leaders from Amazon and Uber. They came to network. And a pithy marquee on the theater summed up their unifying mission: “Queer. Inclusive. Badass.”

The sixth-annual Lesbians Who Tech + Allies Summit was the largest LGBTQ event in the world. The attendees were roughly 80 percent queer women–but sexuality was just one element of diversity. Of those who spoke on stage, half were women of color, 30 percent were black or Latinx, and 15 percent transgender or gender non-conforming.

“We are 100 percent about providing value to queer women. We just don’t have this type of community anywhere else in the world,” said Leanne Pittsford, the founder of Lesbians Who Tech. “That we can do this and be visible and also host a damn good tech conference–that inspires people.”

The Summit is not only a place where leaders such as Sheryl Sandberg and Hillary Clinton fly in to speak, but also the physical gathering of just a fraction of the 50,000 members of the parent organization, Lesbians Who Tech, a social enterprise that Pittsford founded in 2013 and which has grown to 42 cities. In 2019, the organization is entering an inflection point, as what was once a conference-media business with a charitable arm aims to become a scalable technology company. “We already work with more than 150 companies looking to retain or recruit diverse talent,” Pittsford said. “Our partners were asking: How do we track hires? How do we actually hold ourselves accountable?” Now, she and LWT are building Include.io, a digital tool that aims to do precisely that.

Before Pittsford dreamed up her organization, she had been analyzing data and building online fundraising tools for a group opposing Proposition 8, a California ballot measure that would have eliminated rights of same-sex couples to marry. She says she was shocked to discover that the people funding the LGBTQ movement were majority white cisgender men, a term that refers to men who identify with the gender with which they were born. “It was a clear wake-up call for me. The people who would benefit from the movement weren’t funding it. Even the women with the money weren’t spending it,” she said.

Simultaneously, she realized that tech events for the queer community in and around San Francisco always seemed to be 90 percent male. “There’s nothing for us,” she said. No cohesive community, no gathering, no movement, no money spending–even for those women who identified as queer in lucrative Silicon Valley jobs. She wondered: could someone or something change that? Could she change that?

Finding a Purpose, and an Audience

Pittsford grew up in a conservative military family in San Diego, and in the early 2000s was living in San Francisco with her brother. As adults, they still struggled with having been taught as kids that all gay people were going to hell. With support from her brother, and working for a pro-LGBTQ human rights organization, Pittsford became more comfortable with her sexuality. Then, one Tuesday morning in 2010 she arrived home to discover that her brother–the only supportive person in her life–had died in his sleep of cardiomyopathy. “My heart was just broken,” she says. “It gave me a sense that I should take risks, give back and do something larger than myself.”

Pittsford’s grief was heavy that year, in which she left her comfortable job doing policy work at Equity California. “I was close to [starting my own venture], but that moment really sped it up for me,” she said. She started working independently, doing data work, and building websites and tools for other businesses.

In the evenings, she subverted her introversion and began networking, and throwing small happy hours for queer women. In 2014 she decided to host what she dubbed a “Summit” for her burgeoning organization, Lesbians Who Tech. It was to be part networking with like-minded people, part technology conference, and part social-justice rally. “I thought it wouldn’t work,” she said. “Because lesbians never show up, they never go out.”

Megan Smith, a vice president at Google who would soon be tapped to be the chief technology officer of the United States by President Barack Obama, walked in the door at 7 a.m. Next, Smith’s then-partner Kara Swisher walked in. Eight hundred people bought tickets–and a few big companies sponsored it. Pittsford was floored: “It was the first time I thought it could be a real thing.”

Over the past six years, the conferences have gained a cult following among queer technologists and executives. LaFawn Davis, the head of inclusion and culture at Twilio, has attended multiple LWT conferences, and adores them so much she jokes they are “lesbian Disneyland.” For her, the long weekends are a chance to immerse herself in a community that is still rare in the tech world. “I get to be surrounded by queer executives! Queer engineers! Imagine!” And over the years she’s also built a network and found job candidates through it.

The Lesbians Who Tech parent organization, though, is an unusual enterprise: it’s part 501(c)(3) and part LLC; a community organization that offers substantial coding scholarships to women, and a mission-driven media business that puts on conferences.

By 2017, Pittsford realized she needed to solve LWT’s messy structural issue. The organization would need real profits to grow, and to give its now-massive network significant value outside of the conferences. “I came from the nonprofit space, and it’s not the most scalable path,” she said.

Holding Tech Accountable

Aside from ticket sales, the conferences generated revenue through sponsors such as Google, Amazon, and Slack, who also would send speakers and attendees to the events. LWT became a natural recruiting tool for them–but it was totally informal. Once executives at these companies started asking Pittsford how they could improve their diversity hiring and retention and track it, she saw the future of her business before her eyes.

LWT could offer a hiring platform featuring its members, which the organization describes as mid-level and executive LGBTQ women, non-binary, and trans techies–many of whom are also people of color–as well as their allies. The platform could help companies track their ongoing progress in diversity hiring. Pittsford envisioned Include.io, which has 10,000 beta users, as a way to “scale access to direct referrals” from a different pool of talent than the existing employees at large tech companies.

“We are trying to find a way to get referrals to, say, the talented self-taught female programmer in New Orleans who might not know anyone in San Francisco,” Pittsford said.

“Things like unconscious bias training aren’t working,” she added. “You have to fight it every day–with intention–and this product lets companies do that.”

Include.io has been in beta since June of 2018, and Pittsford says 200 companies have signed up to use it once it’s live later this year. But she has some structural work to do before launch. The company’s Oakland office hasn’t attracted or retained enough tech talent itself to scale Include.io, so she’s setting up a development team in New York, hoping to add three to five more people to the scrappy staff of nine. She says San Francisco is the “Wild West of talent poaching,” where small organizations can’t compete for developers who can command salaries approaching $200,000.

“This has been the hardest year of my professional life,” she said. She’s running a mission-driven organization at the speed of a startup, trying to figure out how fast it can grow and scale without burning out her team–or herself.

Being part of the solution to tech’s diversity problem, however, is what keeps her going every day. Pittsford says she hopes once Include.io is out to the public, it will make executives more comfortable about their own abilities to recruit, hire, and maintain a diverse workforce.

“I still would love to see a CEO say, ‘we are going to be 30 percent black and Latinx by X year,'” she said. “We really feel like something has got to change. Something has got to give.”

0 notes

Text

More Than 150 Companies Are Hoping This Woman Can Fix Their Diversity Problems

New Post has been published on http://web-hosting-top12.com/2019/04/05/more-than-150-companies-are-hoping-this-woman-can-fix-their-diversity-problems/

More Than 150 Companies Are Hoping This Woman Can Fix Their Diversity Problems

For three days in February, 6,000 of people coursed in and out of the Castro Theater, a 1920s movie palace in San Francisco. They came to hear from Laurene Powell Jobs, Susan Wojcicki, and leaders from Amazon and Uber. They came to network. And a pithy marquee on the theater summed up their unifying mission: “Queer. Inclusive. Badass.”

The sixth-annual Lesbians Who Tech + Allies Summit was the largest LGBTQ event in the world. The attendees were roughly 80 percent queer women–but sexuality was just one element of diversity. Of those who spoke on stage, half were women of color, 30 percent were black or Latinx, and 15 percent transgender or gender non-conforming.

“We are 100 percent about providing value to queer women. We just don’t have this type of community anywhere else in the world,” said Leanne Pittsford, the founder of Lesbians Who Tech. “That we can do this and be visible and also host a damn good tech conference–that inspires people.”

The Summit is not only a place where leaders such as Sheryl Sandberg and Hillary Clinton fly in to speak, but also the physical gathering of just a fraction of the 50,000 members of the parent organization, Lesbians Who Tech, a social enterprise that Pittsford founded in 2013 and which has grown to 42 cities. In 2019, the organization is entering an inflection point, as what was once a conference-media business with a charitable arm aims to become a scalable technology company. “We already work with more than 150 companies looking to retain or recruit diverse talent,” Pittsford said. “Our partners were asking: How do we track hires? How do we actually hold ourselves accountable?” Now, she and LWT are building Include.io, a digital tool that aims to do precisely that.

Before Pittsford dreamed up her organization, she had been analyzing data and building online fundraising tools for a group opposing Proposition 8, a California ballot measure that would have eliminated rights of same-sex couples to marry. She says she was shocked to discover that the people funding the LGBTQ movement were majority white cisgender men, a term that refers to men who identify with the gender with which they were born. “It was a clear wake-up call for me. The people who would benefit from the movement weren’t funding it. Even the women with the money weren’t spending it,” she said.

Simultaneously, she realized that tech events for the queer community in and around San Francisco always seemed to be 90 percent male. “There’s nothing for us,” she said. No cohesive community, no gathering, no movement, no money spending–even for those women who identified as queer in lucrative Silicon Valley jobs. She wondered: could someone or something change that? Could she change that?

Finding a Purpose, and an Audience

Pittsford grew up in a conservative military family in San Diego, and in the early 2000s was living in San Francisco with her brother. As adults, they still struggled with having been taught as kids that all gay people were going to hell. With support from her brother, and working for a pro-LGBTQ human rights organization, Pittsford became more comfortable with her sexuality. Then, one Tuesday morning in 2010 she arrived home to discover that her brother–the only supportive person in her life–had died in his sleep of cardiomyopathy. “My heart was just broken,” she says. “It gave me a sense that I should take risks, give back and do something larger than myself.”

Pittsford’s grief was heavy that year, in which she left her comfortable job doing policy work at Equity California. “I was close to [starting my own venture], but that moment really sped it up for me,” she said. She started working independently, doing data work, and building websites and tools for other businesses.

In the evenings, she subverted her introversion and began networking, and throwing small happy hours for queer women. In 2014 she decided to host what she dubbed a “Summit” for her burgeoning organization, Lesbians Who Tech. It was to be part networking with like-minded people, part technology conference, and part social-justice rally. “I thought it wouldn’t work,” she said. “Because lesbians never show up, they never go out.”

Megan Smith, a vice president at Google who would soon be tapped to be the chief technology officer of the United States by President Barack Obama, walked in the door at 7 a.m. Next, Smith’s then-partner Kara Swisher walked in. Eight hundred people bought tickets–and a few big companies sponsored it. Pittsford was floored: “It was the first time I thought it could be a real thing.”

Over the past six years, the conferences have gained a cult following among queer technologists and executives. LaFawn Davis, the head of inclusion and culture at Twilio, has attended multiple LWT conferences, and adores them so much she jokes they are “lesbian Disneyland.” For her, the long weekends are a chance to immerse herself in a community that is still rare in the tech world. “I get to be surrounded by queer executives! Queer engineers! Imagine!” And over the years she’s also built a network and found job candidates through it.

The Lesbians Who Tech parent organization, though, is an unusual enterprise: it’s part 501(c)(3) and part LLC; a community organization that offers substantial coding scholarships to women, and a mission-driven media business that puts on conferences.

By 2017, Pittsford realized she needed to solve LWT’s messy structural issue. The organization would need real profits to grow, and to give its now-massive network significant value outside of the conferences. “I came from the nonprofit space, and it’s not the most scalable path,” she said.

Holding Tech Accountable

Aside from ticket sales, the conferences generated revenue through sponsors such as Google, Amazon, and Slack, who also would send speakers and attendees to the events. LWT became a natural recruiting tool for them–but it was totally informal. Once executives at these companies started asking Pittsford how they could improve their diversity hiring and retention and track it, she saw the future of her business before her eyes.

LWT could offer a hiring platform featuring its members, which the organization describes as mid-level and executive LGBTQ women, non-binary, and trans techies–many of whom are also people of color–as well as their allies. The platform could help companies track their ongoing progress in diversity hiring. Pittsford envisioned Include.io, which has 10,000 beta users, as a way to “scale access to direct referrals” from a different pool of talent than the existing employees at large tech companies.

“We are trying to find a way to get referrals to, say, the talented self-taught female programmer in New Orleans who might not know anyone in San Francisco,” Pittsford said.

“Things like unconscious bias training aren’t working,” she added. “You have to fight it every day–with intention–and this product lets companies do that.”

Include.io has been in beta since June of 2018, and Pittsford says 200 companies have signed up to use it once it’s live later this year. But she has some structural work to do before launch. The company’s Oakland office hasn’t attracted or retained enough tech talent itself to scale Include.io, so she’s setting up a development team in New York, hoping to add three to five more people to the scrappy staff of nine. She says San Francisco is the “Wild West of talent poaching,” where small organizations can’t compete for developers who can command salaries approaching $200,000.

“This has been the hardest year of my professional life,” she said. She’s running a mission-driven organization at the speed of a startup, trying to figure out how fast it can grow and scale without burning out her team–or herself.

Being part of the solution to tech’s diversity problem, however, is what keeps her going every day. Pittsford says she hopes once Include.io is out to the public, it will make executives more comfortable about their own abilities to recruit, hire, and maintain a diverse workforce.

“I still would love to see a CEO say, ‘we are going to be 30 percent black and Latinx by X year,'” she said. “We really feel like something has got to change. Something has got to give.”

0 notes

Text

More Than 150 Companies Are Hoping This Woman Can Fix Their Diversity Problems

New Post has been published on http://web-hosting-top12.com/2019/04/05/more-than-150-companies-are-hoping-this-woman-can-fix-their-diversity-problems/

More Than 150 Companies Are Hoping This Woman Can Fix Their Diversity Problems

For three days in February, 6,000 of people coursed in and out of the Castro Theater, a 1920s movie palace in San Francisco. They came to hear from Laurene Powell Jobs, Susan Wojcicki, and leaders from Amazon and Uber. They came to network. And a pithy marquee on the theater summed up their unifying mission: “Queer. Inclusive. Badass.”

The sixth-annual Lesbians Who Tech + Allies Summit was the largest LGBTQ event in the world. The attendees were roughly 80 percent queer women–but sexuality was just one element of diversity. Of those who spoke on stage, half were women of color, 30 percent were black or Latinx, and 15 percent transgender or gender non-conforming.

“We are 100 percent about providing value to queer women. We just don’t have this type of community anywhere else in the world,” said Leanne Pittsford, the founder of Lesbians Who Tech. “That we can do this and be visible and also host a damn good tech conference–that inspires people.”

The Summit is not only a place where leaders such as Sheryl Sandberg and Hillary Clinton fly in to speak, but also the physical gathering of just a fraction of the 50,000 members of the parent organization, Lesbians Who Tech, a social enterprise that Pittsford founded in 2013 and which has grown to 42 cities. In 2019, the organization is entering an inflection point, as what was once a conference-media business with a charitable arm aims to become a scalable technology company. “We already work with more than 150 companies looking to retain or recruit diverse talent,” Pittsford said. “Our partners were asking: How do we track hires? How do we actually hold ourselves accountable?” Now, she and LWT are building Include.io, a digital tool that aims to do precisely that.

Before Pittsford dreamed up her organization, she had been analyzing data and building online fundraising tools for a group opposing Proposition 8, a California ballot measure that would have eliminated rights of same-sex couples to marry. She says she was shocked to discover that the people funding the LGBTQ movement were majority white cisgender men, a term that refers to men who identify with the gender with which they were born. “It was a clear wake-up call for me. The people who would benefit from the movement weren’t funding it. Even the women with the money weren’t spending it,” she said.

Simultaneously, she realized that tech events for the queer community in and around San Francisco always seemed to be 90 percent male. “There’s nothing for us,” she said. No cohesive community, no gathering, no movement, no money spending–even for those women who identified as queer in lucrative Silicon Valley jobs. She wondered: could someone or something change that? Could she change that?

Finding a Purpose, and an Audience

Pittsford grew up in a conservative military family in San Diego, and in the early 2000s was living in San Francisco with her brother. As adults, they still struggled with having been taught as kids that all gay people were going to hell. With support from her brother, and working for a pro-LGBTQ human rights organization, Pittsford became more comfortable with her sexuality. Then, one Tuesday morning in 2010 she arrived home to discover that her brother–the only supportive person in her life–had died in his sleep of cardiomyopathy. “My heart was just broken,” she says. “It gave me a sense that I should take risks, give back and do something larger than myself.”

Pittsford’s grief was heavy that year, in which she left her comfortable job doing policy work at Equity California. “I was close to [starting my own venture], but that moment really sped it up for me,” she said. She started working independently, doing data work, and building websites and tools for other businesses.

In the evenings, she subverted her introversion and began networking, and throwing small happy hours for queer women. In 2014 she decided to host what she dubbed a “Summit” for her burgeoning organization, Lesbians Who Tech. It was to be part networking with like-minded people, part technology conference, and part social-justice rally. “I thought it wouldn’t work,” she said. “Because lesbians never show up, they never go out.”

Megan Smith, a vice president at Google who would soon be tapped to be the chief technology officer of the United States by President Barack Obama, walked in the door at 7 a.m. Next, Smith’s then-partner Kara Swisher walked in. Eight hundred people bought tickets–and a few big companies sponsored it. Pittsford was floored: “It was the first time I thought it could be a real thing.”

Over the past six years, the conferences have gained a cult following among queer technologists and executives. LaFawn Davis, the head of inclusion and culture at Twilio, has attended multiple LWT conferences, and adores them so much she jokes they are “lesbian Disneyland.” For her, the long weekends are a chance to immerse herself in a community that is still rare in the tech world. “I get to be surrounded by queer executives! Queer engineers! Imagine!” And over the years she’s also built a network and found job candidates through it.

The Lesbians Who Tech parent organization, though, is an unusual enterprise: it’s part 501(c)(3) and part LLC; a community organization that offers substantial coding scholarships to women, and a mission-driven media business that puts on conferences.

By 2017, Pittsford realized she needed to solve LWT’s messy structural issue. The organization would need real profits to grow, and to give its now-massive network significant value outside of the conferences. “I came from the nonprofit space, and it’s not the most scalable path,” she said.

Holding Tech Accountable

Aside from ticket sales, the conferences generated revenue through sponsors such as Google, Amazon, and Slack, who also would send speakers and attendees to the events. LWT became a natural recruiting tool for them–but it was totally informal. Once executives at these companies started asking Pittsford how they could improve their diversity hiring and retention and track it, she saw the future of her business before her eyes.

LWT could offer a hiring platform featuring its members, which the organization describes as mid-level and executive LGBTQ women, non-binary, and trans techies–many of whom are also people of color–as well as their allies. The platform could help companies track their ongoing progress in diversity hiring. Pittsford envisioned Include.io, which has 10,000 beta users, as a way to “scale access to direct referrals” from a different pool of talent than the existing employees at large tech companies.

“We are trying to find a way to get referrals to, say, the talented self-taught female programmer in New Orleans who might not know anyone in San Francisco,” Pittsford said.

“Things like unconscious bias training aren’t working,” she added. “You have to fight it every day–with intention–and this product lets companies do that.”

Include.io has been in beta since June of 2018, and Pittsford says 200 companies have signed up to use it once it’s live later this year. But she has some structural work to do before launch. The company’s Oakland office hasn’t attracted or retained enough tech talent itself to scale Include.io, so she’s setting up a development team in New York, hoping to add three to five more people to the scrappy staff of nine. She says San Francisco is the “Wild West of talent poaching,” where small organizations can’t compete for developers who can command salaries approaching $200,000.

“This has been the hardest year of my professional life,” she said. She’s running a mission-driven organization at the speed of a startup, trying to figure out how fast it can grow and scale without burning out her team–or herself.

Being part of the solution to tech’s diversity problem, however, is what keeps her going every day. Pittsford says she hopes once Include.io is out to the public, it will make executives more comfortable about their own abilities to recruit, hire, and maintain a diverse workforce.

“I still would love to see a CEO say, ‘we are going to be 30 percent black and Latinx by X year,'” she said. “We really feel like something has got to change. Something has got to give.”

0 notes

Text

More Than 150 Companies Are Hoping This Woman Can Fix Their Diversity Problems

New Post has been published on http://web-hosting-top12.com/2019/04/05/more-than-150-companies-are-hoping-this-woman-can-fix-their-diversity-problems/

More Than 150 Companies Are Hoping This Woman Can Fix Their Diversity Problems

For three days in February, 6,000 of people coursed in and out of the Castro Theater, a 1920s movie palace in San Francisco. They came to hear from Laurene Powell Jobs, Susan Wojcicki, and leaders from Amazon and Uber. They came to network. And a pithy marquee on the theater summed up their unifying mission: “Queer. Inclusive. Badass.”

The sixth-annual Lesbians Who Tech + Allies Summit was the largest LGBTQ event in the world. The attendees were roughly 80 percent queer women–but sexuality was just one element of diversity. Of those who spoke on stage, half were women of color, 30 percent were black or Latinx, and 15 percent transgender or gender non-conforming.

“We are 100 percent about providing value to queer women. We just don’t have this type of community anywhere else in the world,” said Leanne Pittsford, the founder of Lesbians Who Tech. “That we can do this and be visible and also host a damn good tech conference–that inspires people.”

The Summit is not only a place where leaders such as Sheryl Sandberg and Hillary Clinton fly in to speak, but also the physical gathering of just a fraction of the 50,000 members of the parent organization, Lesbians Who Tech, a social enterprise that Pittsford founded in 2013 and which has grown to 42 cities. In 2019, the organization is entering an inflection point, as what was once a conference-media business with a charitable arm aims to become a scalable technology company. “We already work with more than 150 companies looking to retain or recruit diverse talent,” Pittsford said. “Our partners were asking: How do we track hires? How do we actually hold ourselves accountable?” Now, she and LWT are building Include.io, a digital tool that aims to do precisely that.

Before Pittsford dreamed up her organization, she had been analyzing data and building online fundraising tools for a group opposing Proposition 8, a California ballot measure that would have eliminated rights of same-sex couples to marry. She says she was shocked to discover that the people funding the LGBTQ movement were majority white cisgender men, a term that refers to men who identify with the gender with which they were born. “It was a clear wake-up call for me. The people who would benefit from the movement weren’t funding it. Even the women with the money weren’t spending it,” she said.

Simultaneously, she realized that tech events for the queer community in and around San Francisco always seemed to be 90 percent male. “There’s nothing for us,” she said. No cohesive community, no gathering, no movement, no money spending–even for those women who identified as queer in lucrative Silicon Valley jobs. She wondered: could someone or something change that? Could she change that?

Finding a Purpose, and an Audience

Pittsford grew up in a conservative military family in San Diego, and in the early 2000s was living in San Francisco with her brother. As adults, they still struggled with having been taught as kids that all gay people were going to hell. With support from her brother, and working for a pro-LGBTQ human rights organization, Pittsford became more comfortable with her sexuality. Then, one Tuesday morning in 2010 she arrived home to discover that her brother–the only supportive person in her life–had died in his sleep of cardiomyopathy. “My heart was just broken,” she says. “It gave me a sense that I should take risks, give back and do something larger than myself.”

Pittsford’s grief was heavy that year, in which she left her comfortable job doing policy work at Equity California. “I was close to [starting my own venture], but that moment really sped it up for me,” she said. She started working independently, doing data work, and building websites and tools for other businesses.

In the evenings, she subverted her introversion and began networking, and throwing small happy hours for queer women. In 2014 she decided to host what she dubbed a “Summit” for her burgeoning organization, Lesbians Who Tech. It was to be part networking with like-minded people, part technology conference, and part social-justice rally. “I thought it wouldn’t work,” she said. “Because lesbians never show up, they never go out.”

Megan Smith, a vice president at Google who would soon be tapped to be the chief technology officer of the United States by President Barack Obama, walked in the door at 7 a.m. Next, Smith’s then-partner Kara Swisher walked in. Eight hundred people bought tickets–and a few big companies sponsored it. Pittsford was floored: “It was the first time I thought it could be a real thing.”

Over the past six years, the conferences have gained a cult following among queer technologists and executives. LaFawn Davis, the head of inclusion and culture at Twilio, has attended multiple LWT conferences, and adores them so much she jokes they are “lesbian Disneyland.” For her, the long weekends are a chance to immerse herself in a community that is still rare in the tech world. “I get to be surrounded by queer executives! Queer engineers! Imagine!” And over the years she’s also built a network and found job candidates through it.

The Lesbians Who Tech parent organization, though, is an unusual enterprise: it’s part 501(c)(3) and part LLC; a community organization that offers substantial coding scholarships to women, and a mission-driven media business that puts on conferences.

By 2017, Pittsford realized she needed to solve LWT’s messy structural issue. The organization would need real profits to grow, and to give its now-massive network significant value outside of the conferences. “I came from the nonprofit space, and it’s not the most scalable path,” she said.

Holding Tech Accountable

Aside from ticket sales, the conferences generated revenue through sponsors such as Google, Amazon, and Slack, who also would send speakers and attendees to the events. LWT became a natural recruiting tool for them–but it was totally informal. Once executives at these companies started asking Pittsford how they could improve their diversity hiring and retention and track it, she saw the future of her business before her eyes.

LWT could offer a hiring platform featuring its members, which the organization describes as mid-level and executive LGBTQ women, non-binary, and trans techies–many of whom are also people of color–as well as their allies. The platform could help companies track their ongoing progress in diversity hiring. Pittsford envisioned Include.io, which has 10,000 beta users, as a way to “scale access to direct referrals” from a different pool of talent than the existing employees at large tech companies.

“We are trying to find a way to get referrals to, say, the talented self-taught female programmer in New Orleans who might not know anyone in San Francisco,” Pittsford said.

“Things like unconscious bias training aren’t working,” she added. “You have to fight it every day–with intention–and this product lets companies do that.”

Include.io has been in beta since June of 2018, and Pittsford says 200 companies have signed up to use it once it’s live later this year. But she has some structural work to do before launch. The company’s Oakland office hasn’t attracted or retained enough tech talent itself to scale Include.io, so she’s setting up a development team in New York, hoping to add three to five more people to the scrappy staff of nine. She says San Francisco is the “Wild West of talent poaching,” where small organizations can’t compete for developers who can command salaries approaching $200,000.

“This has been the hardest year of my professional life,” she said. She’s running a mission-driven organization at the speed of a startup, trying to figure out how fast it can grow and scale without burning out her team–or herself.

Being part of the solution to tech’s diversity problem, however, is what keeps her going every day. Pittsford says she hopes once Include.io is out to the public, it will make executives more comfortable about their own abilities to recruit, hire, and maintain a diverse workforce.

“I still would love to see a CEO say, ‘we are going to be 30 percent black and Latinx by X year,'” she said. “We really feel like something has got to change. Something has got to give.”

0 notes

Text

More Than 150 Companies Are Hoping This Woman Can Fix Their Diversity Problems

New Post has been published on http://web-hosting-top12.com/2019/04/05/more-than-150-companies-are-hoping-this-woman-can-fix-their-diversity-problems/

More Than 150 Companies Are Hoping This Woman Can Fix Their Diversity Problems

For three days in February, 6,000 of people coursed in and out of the Castro Theater, a 1920s movie palace in San Francisco. They came to hear from Laurene Powell Jobs, Susan Wojcicki, and leaders from Amazon and Uber. They came to network. And a pithy marquee on the theater summed up their unifying mission: “Queer. Inclusive. Badass.”

The sixth-annual Lesbians Who Tech + Allies Summit was the largest LGBTQ event in the world. The attendees were roughly 80 percent queer women–but sexuality was just one element of diversity. Of those who spoke on stage, half were women of color, 30 percent were black or Latinx, and 15 percent transgender or gender non-conforming.

“We are 100 percent about providing value to queer women. We just don’t have this type of community anywhere else in the world,” said Leanne Pittsford, the founder of Lesbians Who Tech. “That we can do this and be visible and also host a damn good tech conference–that inspires people.”