#again arcane is not a morality contest

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Best of D&D Comics Characters

There have been a lot of comics made or inspired by Dungeons & Dragons. A lot of them are crap, as most things are, but there are some real gems among them to wet any fantasy pallet.

For this list, I will go through each major class and choose one character for each to represent the ‘best’ of that class. There will be some honorable mentions, but this is my list, so I’ll do what I want. Sadly, newer classes like Artificer don’t have enough characters in comics to really work.

Barbarian - When I think of Barbarians, I think big. So for this slot, I’ll go with Grog Strongjaw, a Goliath Barbarian from the first campaign of Critical Role. There wasn’t much competition in the field. Yasha from the second run of Critical Role and Lux from the made for TV-Movie and not TV-Pilot Dungeons and Dragons: Curse of the Dragon God are about the only real competition he had.

What about Bobby from the Animated Show?

What ABOUT Bobby from the animated show?

Bard - Bards are a strange bunch by design. They have to be charismatic, but they are also among the goofiest in play. To go with that feel, the only logical choice was Elan from Order of the Stick. No one else even came close. It’s the most meta choice.

Cleric - Cleric is a hard choice because it is often seen as the blandest of classes. Goody-good healer, or stick in the mud morality police in narratives. And this is despite their versatility and being probably the most broken class in the game. So I went with Nerys Kathon from Jim Zub’s Baldur’s Gate comics. She’s a priestess of Kelemvor, which makes her goth look all the more appropriate. And who can say no to a badass goth girl?

Druid - Druids are rare in multimedia about D&D as far as I’ve been able to find. I haven’t read many of the books, but I’ve read a lot of comics. And I mean a LOT. Still, the field wasn’t completely empty. Keyleth from Critical Role Campaign 1 easily stood out.

Fighter - The most common thing in D&D, according to statistics, is Human Fighter, so it should be no surprise that this one ended in a tie among human fighters. Adric Fell from John Roger’s D&D Comic and leader of “Fells FIve,” and Vajra Valmejar from Advanced Dungeons & Dragons from DC comics back in the day. Adric Fell has wit, charm, cunning. and one weird implied history (uses a cavalry saber, writes contracts using pirate slang). Vajra is a survivor. And also a black woman who is in effect the lead character of the entire run. From the 1980s. In a D&D comic.

That’s impressive all by itself.

Monk - There are even fewer monks than druids in D&D comics. In the end, it was either Beau from Critical Role Campaign 2 or the Pathfinder Iconic Monk who I can’t recall the name of and am not bothering to look up because Beau is an easy win. Her backstory alone makes her more interesting than an Iconic.

Paladin - Paladin was a bit thicker despite being the best ‘newb’ class, but not by much, but again, it was no contest. Khal Khalundurrin, Dwarven Paladin, former “Rebel Rockstar Bard” turned Holyman from John Rogers comic and member of Fell’s Five. I mean, look at that! That’s the kind of backstory that I can get behind!

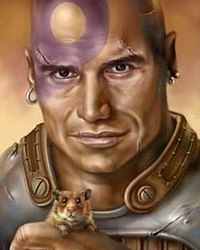

Ranger - This was probably the hardest. I mean, Dritz. He’s ... Everywhere. But I couldn’t really get behind him. So, I went with Minsc. He has a miniature Giant Space Hamster as an animal companion. Need I say more?

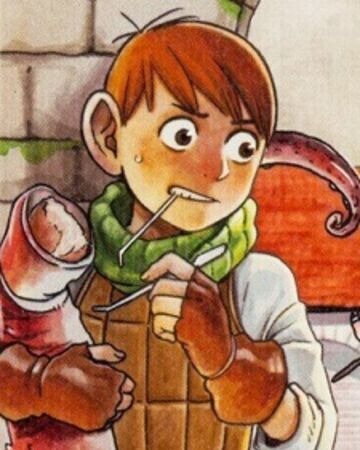

Rogue - Rogues in D&D media tend to be halflings. In modern times, most halflings tend to be stabby. So, to buck the trend, I went with Chilchuck from Delicious in Dungeon, which is probably the best unofficial D&D manga on the market. And it’s about cooking.

Sorcerer - Sorcerers are another rare class in D&D media. Wizards getting a favorable bias in representing arcane magic in D&D.

...

ESPECIALLY THE WIZARD

...

Sorry, I had to.

Anyway, I went with Delina from Jim Zub’s D&D comic. Because as a wild mage, her abilities become “Wild Magic Narrative Convenience 1/Story” which is just perfect, IMO.

Warlock - Warlocks are a relatively new class, but they have been around long enough to gain a few good characters to work with. Though, again, I find myself almost defaulting to John Roger’s D&D comic and Fell’s Five: Tisha Swornheart. A Starpact Warlock Tiefling out for revenge against her own sister.

Wizard - There were a lot of wizards to go through, but most were in the Gandalf/Dumbledore mold and who needs that derivative stuff. So I went with Marcille from Delicious in Dungeon for being nothing like those archetypes, and for a touch of darkness to her. Plus, she knows how to make soap! Does your wizard know how to make soap? I didn’t think so!

Not bad. A nice mix. We’ve got 2 characters from Delicious in Dungeon. 3 from Critical Role. 3 From Jim Zub’s D&D comic Legends of Baldur’s Gate. 3 From John Rogers D&D comic.

Not a bad spread.

But who do you think is the best/most interesting representative of each class?

9 notes

·

View notes

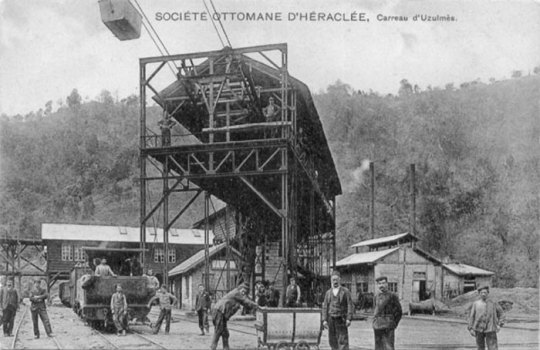

Photo

LOCAL NOTABLES, STATE CAPITALISTS, AND THE PRICE OF "PROGRESS" IN THE EREÔLÎ COALFIELDS “Emin Muhlis' actions directly affected the lives of local elites and nonelites alike, with degrees of severity inversely proportional to class status and political influence. His self-identified victims ranged from farmhands and boatmen to some of the most powerful and influential families. Yet, the attention this case received - generating a case file consisting of hundreds of documents - reflects the fact that Emin Muhlis’ actions played out within an even broader historical tableaux that was dominated by conflicts around power, wealth, and control over the region's bountiful and increasingly profitable coal deposits. Initially, these struggles had primarily involved local notable families, but over the course of the 19th century they began to involve actors at imperial and global levels. Nearly a century before the investigation of the kaymakam, two notable families of the region were battling over the new coal resources that held such a promising future. The winners went on to prosperity and influence, and the losers slipped into a genteel cocoon of soft power. During the 1820s, the ultimate victors of our local contest, the family of the sons of Kara Mahmud (Karamahmudzadeler), appeared to be the weaker party rivals, the family of the sons of Haci ismail (Haciismailogullari), were local officials with real influence and seemed to be better placed to take advantage of the new era. In one version of the discovery story credits a Haci Ismail family member with the discovery, one that led nowhere. As luck would have it, readily accessible deposits were located in a particular Eregli-area village controlled by the Karamahmudzade family And so, when that discovery was announced and bore results, the Haci Ismail clan, angered by the sudden enrichment of their rivals, allegedly murdered the discoverer. Subsequently, the Karamahmudzade family became the most influential family in Eregli region, based on its possession of many of the richest and most accessible mines. In the late 1870s, for example, Halil of the Karamahmudzade family held the prestige duty of buying sheep for the Ramadan celebrations in the coalfield. By the end 19th century, one brother was a member of the Eregli district council while another sat on the Eregli city council. The Haci ismail family is less visible in the record, but it also prospered in the trade, providing timber for the mines. Eight decades after their initial struggle over access to the riches of the coalfields, the two families again were intertwined but this time in alliance against Emin Muhlis. Three members of the Karamahmudzade family appeared before the investigator, a measure of their power and influence, while only one Haci ismailoglu member was questioned. Their combined testimonies provided the greatest volume of detail regarding the kaymakaman’s illicit activities, financial and otherwise. Furthermore, their words did not hide the deep disregard in which they held Emin Muhlis. Haciismailagazade Hakki Bey, whose testimony was perhaps the longest of those provided to the investigator, purported to speak on behalf of the entire community, Christian and Muslim alike. His knowledge of a host of arcane fiscal issues and his intimate awareness of the kaymakam’s abuses of power indicated his family's still considerable prestige and deep involvement in community affairs. As mentioned previously, Hakki had drafted the 30 June 1905 telegram to the grand vizier that finally triggered the interrogation proceedings about the kaymakam. In his own testimony, Hakki categorically condemned Emin Muhlis, from all sides - fiscal, administrative, and moral. He excoriated the kaymakam for his wanton use of the sources of local wealth for personal enrichment and enumerated the many properties illegally acquired. His and other statements demonstrate the kaymakam's meticulous and painstaking use of the smallest revenue sources to accumulate wealth. Hakki also sympathetically detailed the imprisonment of the village headmen who continued to insist that their villages owed mine labor to Karamahmudzade Halil and not Ragip Pasa. He even pointed out the jailing of Halil's shepherd. By defending the rights of his once and future enemy of the Karamahmudzade family, Hakki was allying with him against this new threat from outside and asserting a claim to leadership of the local community. Indeed, he called for justice for all of the "wretched and oppressed people of Eregli." Three members of the Karamahmudzade family appeared before the investigator, each offering information of a very specific nature, unlike Hakki's wide-ranging remarks. The first was a junior member of the clan, twenty-year-old Mehmet from Eregli. His striking testimony detailed the shame and humiliation that he had brought upon himself, a member of the leading local family, through his participation in bouts of jollity, drinking, and gambling. He revealed the identities of many of Emin Muhlis' cronies and provided extensive detail regarding their and the kaymakam' s carousing behavior. Another member of the Karamahmudzadeler clan, Mahmud Bey, offered testimony that began with an assault on Emin Muhlis' character and ended with arcane financial details. He contemptuously dismissed the kaymakam's professional training as inadequate and claimed that Emin Muhlis had mishandled his earlier assignments and had risen through incompetence. Settling in Eregli, he had become uncontrolled and abusive, acquiring a wealth well beyond that which could be justified by his salary or family wealth. Mahmud proceeded to provide meticulously detailed testimony regarding Emin Muhlis' many alleged misdeeds. In his recounting of the affair involving the kaymakam' s illegal redirecting of mine labor, Mahmud explicitly linked Emin Muhlis and his actions to Ragip Pasa, claiming that the kaymakam’s primary allegiance was to the pasha and not to his responsibilities as the district's chief official. Finally, Karamahmudzadeler Halil, whose testimony was among the shortest collected by the investigator, provided a reminder of the kaymakam' s notorious cruelty by telling the account of Emin Muhlis' mistreatment of the headmen who chose to defy his orders regarding the provisioning of labor to the mines of Ragip Pasa.

Despite the variety in the language and structure of the four testimonies, their content reflects the shared disdain for Emin Muhlis and his behavior among these erstwhile rival families. However, the kaymakam was not the primary source of their anxieties, which is unmentioned in these statements. Rather, the increasing enmeshing of state power and outside (non-local) capital, both foreign and Ottoman, posed the greatest challenge to these local elite families' sources of livelihood. Reflecting on these interrogations and the events they uncover, I was surprised that the most powerful actor and influence in this drama was hardly visible in the case file. Emin Muhlis certainly is the central visible figure, and the uproar occasioned by his behavior motivated both the investigator's visit and the broader case of which the testimonies he collected are but a part. The kaymakam's role in what is arguably the most important storyline in our drama, the conflict over the region's coal economy, however, is that of a subordinate acting at the beck and call of the true central character - Ragip Pasa. The pasha is scarcely present in the archival documentation used for this article and is usually mentioned in a factual manner when the specific issue of his mines is discussed. Invisible, yes, but he is the actor around whom the drama turned, the force driving the actions of the kaymakam. More important, his background, connections to power, and immense wealth embodied the forces driving the upheavals transforming the economy and society of the district and the conflicts they helped to bring about. This late Ottoman capitalist truly was a powerful personage. Born into a family from the island of Euboea, he received one of the best educations available, graduating from the Galatasarayi School and then the School of Civil Service (Mülkiye Mektebi), two Istanbul institutions responsible for training much of the late Ottoman elite. He reached a position very near the apex of power in the Ottoman world, serving as a chamberlain of the sultan for nearly three decades. In the years around 1900, some 17,000 military and civil personnel rotated in and out of service at the Yildiz Palace of Sultan Abdiilhamit, and fewer than ten of these were chamberlains (kurena), persons in the very inner circle of the monarch, his advisors, and confidants. During the reign of Abdiilhamit II, the sultan personally chose the chamberlains and, at some date before 1880, selected Ragip Pasa, then known only as Ragip Bey. Over the years he served the sultan in countless ways large and small; for example, on one occasion, he co-led (with the well-known Izzet Pa§a) an investigation into a fire that had wracked the palace. Benefiting from his place at the very center of political power and influence, he enjoyed successes in business and actively participated in the major commercial centers of the capital; among other enterprises, he founded the Umurca Raki Factory in Tekirdag. He owned countless farms and apartments. His ability to pay 105,000 gold liras for a home in an emerging elite and fashionable suburb (Caddebostan), where his neighbors included Ottoman and international financial and political leaders, indicates the depth of his wealth. In 1900, Ragip Pasa dramatically entered the coal mining business, purchasing the rights to seventeen mines and obtaining control over a number of vacant mines. The timing, immediately following the entry of the French-financed Eregli Company into the coalfields and a very sharp rise in the production of coal, was no coincidence. Given the sultan's deep concerns over European capital investments in the empire, one can readily imagine the monarch urging on his chamberlain. Ragip Pasa's Sancazadeler Company quickly became a major mining force and technological leader. Within a short time, it was the second largest operation in the coal district, surpassed only by the much larger French-owned Eregli Company. Ragip Pasa's use of personal connections may appear to the present-day reader as corruption (as it did to some of his European contemporaries), but it actually conformed to the standard behavior of the age, when government and private capital acted more openly in tandem. Consider the example of the Wilhelmine state and the financing of the Anatolian and Baghdad railways or, closer to our story, the go-for-broke French support for the Credit Lyonnais' Ottoman coal mine venture. It seems clear, however, that Ragip Pasa's economic successes were closely tied to a more brittle political regime than those of his European capitalist counterparts, and his fate was bound to that of the sultan. While in power, Ragip Pasa constructed a coalfield network of allies and protégés to promote his economic interests that may have eventually reached as high as the governor of Kastamonu province, Nazim Pasa. It is not known when Emin Muhlis fell under his sway, but, as seen, the kaymakam proved to be an effective instrument in aiding the expansion of the pasha's coal mining operations given the former's key political position in the coalfield. Even with the kaymakam's reassignment to Usak in May 1907, and the eventual exit of Ragip Pasa from the coalfields shortly after the Young Turk Revolution, no one really won final victory or suffered permanent defeat in this battle between local and imperial contenders for wealth. The Karamahmudzade and Haciismailoglu families continued to face the power of outside capital. And the deck remained stacked in the favor of outsiders even after Emin Muhlis' departure. Recall Emin Muhlis' attempt to siphon workers away from their legally designated mines to those of Ragip Pasa and his sons. That effort marked the entrepreneur's desperate search for labor for his expanding mine operations. In the months following the investigator's visit in summer 1905, Ragip Pasa lobbied intensively within the imperial and provincial governments for a loosening of the labor regulations to allow the use of mine workers from outside the coalfield district. He won that battle, but despite access to the new sources of mine workers, labor scarcities continued to plague his operations and those of others seeking to exploit the wealth of the coal district's vast reserves. The conflict between the interests of local notables such as the Haci ismail and Karamahmudzade families and those of Emin Muhlis and Ragip Pasa was but a microcosm of a much broader, empire- wide struggle over wealth. The imperial government as well as local and foreign investors separately and together were introducing impressive technological and institutional improvements, producing a steadily more rational state administration and an improving and expanding economic infrastructure. Opportunities for wealth were arising on every side. For Ottoman society as a whole the basic question emerged of who would profit and control the ongoing accumulation. And the testimonies offer a picture of a profoundly corrupted system in which public monies and posts were turned to private profit, a system in which few seemed to do their jobs without recourse to rake-offs and extortion or skimming. Within this context, Emin Muhlis' willingness to so flagrantly use the powers of his office to the benefit of Ragip Pasa helped drive a diverse array of actors in Eregli into an alliance of voices clamoring to the central state for justice and protection. The presence of the locally prominent Haci Ismail and Karamahmudzade families, among other elite groups in the coalition of forces aligning against the kaymakam, no doubt explains why the state took this case seriously enough to conduct an investigation that lasted almost two years. In the eyes of these local elites, Emin Muhlis' primary sin was to ally with Ragip Pasa against the local power brokers and capitalists. Yet, such a view was hardly representative of the entire coalition of complainants that helped to initiate the case against Emin Muhlis. Before concluding, it is important to remember that the testimonies collected by the investigator dispatched by Istanbul drew from a diverse, if not completely representative, subsection of Eregli society. Haci Ismail's pleas on behalf of the "wretched and oppressed people of Eregli” notwithstanding, the complaints and testimonies proffered by non-elite groups demonstrate the gap that separated their experiences of Emin Muhlis' misdeeds, and of the economic and political forces of which his actions were a part, from those of their elite counterparts. For these accusers - dislocated Sufi agriculturalists, merchants, villagers and their headmen, miners, boatmen - the kaymkam 's corrupt behavior was a force that interfered with and even prevented the flow of their everyday lives. The type of justice and protection they sought in giving their statements and complaints was no doubt informed by their own class positions as the rapidly changing political economy of the coalfield impinged on their livelihoods in a manner unfathomable to the Haciismailoglu and Karamahmudzade families.” - Donald Quataert and David Gutman, “COAL MINES, THE PALACE, AND STRUGGLES OVER POWER, CAPITAL, AND JUSTICE IN THE LATE OTTOMAN EMPIRE.” International Journal of Middle East Studies, May 2012, Vol. 44, No. 2 (May 2012), pp. 226-230.

#ereğli#zonguldak#ottoman empire#resource extraction#spoils of empire#government investigation#political corruption#government corruption#civil service#civil servant#local elites#patronage system#resource capitalism#state and labour#coal handlers#coal miners#coal mining#mining town#managing capital#bureaucratic apparatus#ottoman society#ottoman history#istanbul

0 notes